2. Trends in Youth Political Engagement in the UK

We are interested in this article, in particular, in the impact of neo-liberalism on under 18s and young adults. In opinion polling and much academic research, a ‘young’ adult would typically be defined as an 18–24-year-old. However, given that many of the markers traditionally associated with a transition from youth to adulthood, such as entering employment, leaving the parental home, beginning cohabiting relationships or having children, are typically taking place at a later stage in many young people’s lives, as compared to previous generations [

1], we favour a more flexible understanding of a ‘young person’, with adults in their 20s and perhaps well into their 30s still appropriately regarded as relatively ‘young’, especially given the severe financial pressures many ‘young’ people of this age are under, which help drive some of these patterns of behaviour, as well as the relatively high life expectancy in the UK, which currently stands at 82.9 for a female baby born in the UK in 2016 and 79.2 for a boy [

2].

A great deal of attention has been paid in recent years to declining levels of voter turnout and engagement with traditional political and social institutions in established democracies—from political parties, to trade unions, to religious organisations [

3,

4]. In a British context, recent decades have witnessed a rapid decline in political participation in electoral politics, and this trend is particularly marked amongst young people. Voter turnout in general elections remained steady in the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s, averaging between 74 and 75% in each decade, but fell dramatically to just 60% in the 2000s [

5,

6]. The turnout of 18 to 24-year olds seemed to be a growing problem, with turnout being only 3% less than the national average in 1997, rising to over 20% lower in 2010 [

7]. Indeed, in the four general elections prior to 2017 less than half of 18–24-year olds voted [

8]. Moreover, membership of political parties in Britain imploded between the 1980s and 2000s, with the three main parties shedding well over half their members [

9], and with young people being less likely to be a member of a political party than any other age group [

10]. Younger people are also less likely to be in a trade union, and rates of those aged under 50 that are unionised has declined in recent years, whilst increasing for those over 50 [

11].

There is also significant evidence of young people having low levels of political efficacy in Britain (although evidence as to whether it is lower than other age groups remains mixed). Parliament’s report into political disengagement suggests that young people (18–30) are the least likely to believe in the efficacy of political engagement, although they do not markedly differ to other generations in their views towards the political system or politicians specifically [

12]. The Hansard Society’s Audit of Political Engagement found that only a third of participants surveyed believed they could ‘effect political change’, although, interestingly, 18–24-year olds came highest in this group with 41% [

13]. Henn and Foard also found young people’s views towards politicians and political parties to be predominantly negative, and that they lack confidence in their own political knowledge—Henn and Foard do, however, argue that young people are ‘serious and discerning (sceptical) observer-participants of the electoral process, rather than merely uninterested and apathetic onlookers’ [

7] (p. 57). Indeed, research on young people’s political participation has shown that, despite the decline in engagement in conventional politics, young people in the UK (and elsewhere) remain interested in political issues and engage in many forms of civic and political participation [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]. Young people are often, for example, concerned about issues like animal rights and environmentalism and focus on single issue campaigns. They are often active in informal politics and participate in protests, campaigns and acts of political consumerism—i.e., the utilising of market systems themselves as tools to advance political objectives. There is some evidence of the rise of these sorts of consumer acts since the 1970s [

19], with some researchers also suggesting that it is a form of engagement particularly prevalent amongst younger generations [

20], although others [

21] suggest that this apparent rise is artificial, created by the fact that surveys did not used to ask questions pertaining to political consumerism.

Moreover, the historic decline of youth engagement in formal, traditional politics is potentially starting to reverse. Various polls, such as the NME exit poll, and data from both Ipsos MORI and the Essex Continuous Monitoring survey, point to a significant increase in youth turnout in the 2017 general election, as compared to the 2015 election [

22,

23,

24]. Claims of a ‘youthquake’ have been challenged by the British Election Study (BES) team [

25], although their critique rests on problematic data and analysis [

26,

27,

28], and therefore the possibility that there was a significant increase in 18 to 24-year-old turnout cannot be ruled out. Furthermore, the BES team unreasonably define ‘youth’ as coming to an abrupt end at age 25 and their own data points to a clear increase in turnout for 25 to 40-year olds. In addition, membership of the Labour party has increased significantly over the past few years, rising from around 388,000 in December 2015 to about 544,000 members by the end of 2016 [

29] (p. 5), and as both Young and Pickard argue, youth engagement in both of Corbyn’s leadership campaigns and Momentum activism demonstrate a level of influence over events in British politics young people have not had for some time [

30,

31].

In short, evidence suggests that in general citizens are engaging with formal political institutions such as political parties, trade unions and even the state itself, less, and have low levels of efficacy in those institutions, and that this is particularly marked for younger people. This does not seem to be being driven by apathy, however, as other forms of engagement, ‘informal’ and market based, are still occurring, and potentially even increasing. The most recent general election also stands as an important caveat to the continuation of these trends. Much has been written and researched regarding these trends and their possible causes. However, much of this has been undertaken without broader historical, cultural and political analysis. From the other side, works that critically discuss neo-liberalism are often theoretical in nature, with little or insufficient direct empirical backing for their claims. Clearly, then, there is a need for work that attempts to bridge this gap, and we aim here to provide a framework for doing just that. This article seeks to explore a particular set of impacts arising from neo-liberal governmentality, which have had profound implications for political, social and economic life in the UK, linking these to changes in citizens’ subjectivity and subsequent changes in how they approach and understand political institutions and political change.

3. Understanding Neo-Liberalism

Concerns about young people’s levels of participation in mainstream political activities over the last few decades have coincided with the rise and increasing dominance amongst policy-makers, especially in Western Europe, of a set of ideas often labelled as ‘neo-liberal’. But what is neo-liberalism? It does not have a single genealogy but is commonly traced back to the revival of 19th century economic liberalism or classical liberalism, in the US, the UK and the other ‘Anglophone democracies’ in the late 1970s and early 1980s and their growing influence internationally from the 1990s onwards [

32] (p. 98). Classical liberalism is particularly associated with the 18th century Scottish economist and moral philosopher Adam Smith, who argued in the

Wealth of Nations, first published in 1776, that society’s interests are best served by an ‘invisible hand’ of self-interest in the exchange of goods and services in the market and that therefore the market should be subject only to minimal interference by governments [

33]. The term ‘neo-liberal’ was coined by Alexander Rüstow at the ‘Lippmann Colloquium’ in 1938, in which a number of thinkers met to discuss the crisis of liberalism and how best to promote it in the context of the rise of fascism and communism and the dominance of Keynesian economics. Neo-liberalism was contrasted by participants with laissez-faire liberalism as requiring a strong state to protect the free economy [

34].

Contemporary neo-liberalism is best viewed as a form of governmentality (the ‘governing mode of thought’) where the ‘market becomes the principle upon which the whole rest of society is remodelled’ [

35] (p. 349). The concept of governmentality was first developed by Foucault and refers to the governmental techniques deployed to administer citizens, and which attempt to shape their behaviour in various ways so as to create governable subjects [

36]. Neo-liberal governmentality tends to favour policies such as trade liberalisation, the free movement of capital, deregulation, privatisation and austerity and argues against, and is keen to reduce, state intervention in the market (except for the creation and maintenance of markets and competition) and social affairs and specifically is against state-level measures aimed at reducing the high levels of economic inequality that inevitably result from such policies. It advocates citizens (increasingly) taking personal responsibility for their own individual health, education and social security or welfare needs so as not to become a ‘burden’ to the community [

32] (pp. 97–98). These ideas, and their increasing adoption in rhetoric and public policy practice, are often viewed as having led, in the early 1980s, to a ‘paradigm shift’ in the US and the UK away from the post-war consensus, based on Keynesian economic ideas, such as Keynes’s arguments in favour of government intervention to promote employment and price stability, towards a new consensus, of an increasingly international nature, among policy-makers around neo-liberalism; a shift from a Keynesian to a neo-liberal paradigm [

37,

38,

39].

Dardot and Laval argue that key to neo-liberalism is its recognition of the shortcomings of classic liberal thought, including the ‘minimal’ state and laissez-faire approaches, and offers, instead, as a solution, an interventionist state [

40]. This might at first glance seem directly contradictory to the policies typically associated with neo-liberal doctrine, but Dardot and Laval argue that neo-liberals recognise that markets are not as ‘natural’ as some classical liberals assumed—they have to be created. The question then becomes not whether the state

should intervene in the economy but

how. Indeed, Foster, Kerr and Byrne advance an interesting and persuasive argument that processes of depoliticisation and governmentality serve to hide the pervasiveness of state intervention by, on the one hand, making expert professionals and technocrats responsible for some areas of policy and, on the other, normalising certain forms of behaviour among citizens, in line with governmental (neo-liberal) rationality [

41]. Neo-liberalism advocates state intervention with the objective being to bring market rationality to as many sites of human activity as possible, from the functioning of the state itself to individual subjectivity; individuals are increasingly ‘disciplined’ to act in self-optimising, competitive and individualistic ways and the state promotes competition as the universal value by which to order human life [

42,

43,

44,

45,

46]. As Gilbert puts it, ‘neoliberalism, from the moment of its inception, advocates a programme of deliberate intervention by government in order to encourage particular types of entrepreneurial, competitive and commercial behaviour in its citizens’ [

44] (p. 9). The state itself comes to be associated almost entirely with the functioning of the economy [

47] and the ‘ambiguity’ of political discourse is reduced and ‘constrained’ down to economic indicators—as Davies puts it: ‘Neoliberalism is the pursuit of the disenchantment of politics by economics’ [

48] (p. 4).

There are potential questions about the usefulness of neo-liberalism as a factor in understanding contemporary politics, and it can be viewed (and indeed used) as a rather imprecise and vague term. In addition, there are no pure examples of a ‘neo-liberal state’ and there are various other factors that can be used to explain political events and trends. Moreover, those thinkers and politicians typically identified as neo-liberal often have different and conflicting views on particular issues. This has led some to argue against the use of neo-liberalism in academic discourse. In particular, Venugopal has argued that neo-liberalism ‘has become a deeply problematic and incoherent term that has multiple and contradictory meanings’ [

49] (p. 165), concluding that the term is something used by critical scholars ‘to conceive of academic economics and a range of economic phenomena that are otherwise beyond their cognitive horizons and which they cannot otherwise grasp or evaluate’ [

49] (p. 183). Certainly, the implementation of neo-liberalism is a complex, varied process, moderated by geography, personality, and existing social and political conditions, meaning that it looks different in different political contexts and across time, just as there are plenty of other factors pertinent to political participation too. However, our contention here is that neo-liberalism is a significant but underexplored factor in examining youth political engagement that warrants further research and study. We aim with this article to provide a framework in which to do that, with a clear definition of neo-liberalism and its unique approach to economic, social and political issues provided above (in essence a governing ‘rationality’ that aims at placing the value of competition at the heart of all human endeavour, using an interventionist state to do so). And below we set out our own process of attempting to reach a way of quantifying its impact, hopefully mitigating some of the legitimate concerns around the use of the term ‘neo-liberalism’ in research and theory. Peck, Theodore and Brenner also usefully engage with these critiques, characterising neo-liberalism as an incomplete, imperfect project more akin to a ‘syndrome’ that is found in many different political contexts [

50], and Peck views neo-liberalism as often a haphazard, ‘geometric’ project that looks different in different localities and times [

51]. The impacts we explore below, then, should be seen less as essential, fundamental traits of any and every form of neo-liberalism, but rather as broad, actual impacts after over 30 years of neo-liberal-minded policy specifically in the UK.

In the next section, this article will argue that neo-liberalism has transformed the citizen’s relationship with political institutions and markets, with important implications for the possibilities of social change, and that this has been particularly pronounced for younger generations. Moreover, whilst the financial crisis in 2008 highlighted deep flaws in the loose chains of deregulated financial markets favoured by neo-liberalism, the ideology has in fact expanded and deepened its reach since then [

50]. Young people in the UK and other advanced industrial democracies have faced a tough environment marked by the pursuit of austerity and spending cuts in welfare and public services that have impacted disproportionately upon them [

52,

53]. However, the particular relevance of neo-liberalism to youth engagement runs deeper than these recent policy decisions. The ‘millennials’ (those born between the early 1980s and early 2000s) were the first generation to grow up under ‘neo-liberal hegemony’: that is, whatever their differences of policy in certain areas, none of the major political parties in Britain, until the election of Corbyn as Labour leader, challenged the neo-liberal paradigm [

54,

55].

This means that the trends described below, from markedly higher inequality, to privatised public services, to ‘responsibilisation’ cultures, are not new or particularly publicly contested for younger generations—they are the norm for the society and political culture they have grown up in. As Jennings puts it: ‘Young adulthood is the time of identity formation. It is at this age that political history can have a critical impact on a cohort’s political make-up in a direct, experiential fashion… The political significance of the crystallization process lies in the content of that which is crystallizing, the social, political, and historical materials that are being worked over and experienced by the young during these formative years. For it is this content that colors the cohort. If the color differs appreciably from that attached to past cohorts, we have the making of a political generation’ [

56] (p. 347). The values and norms we experience in our formative years can have profound impacts on our own personal values and the political behaviour we do or do not engage in in these years can set a precedent we follow for the rest of our lives. The party that is in power at the time citizens come of age has a potentially long-term impact on a particular cohort as a result of its greater media exposure and impact on the political agenda; young people are particularly likely to be impacted by this process as their identities are still being formed. The argument here then is that the impacts and their attendant subjective experience described below are pertinent to the engagement of the general population, but because they will have been/are being experienced by younger generations in their formative years, with little knowledge of alternatives (indeed, a hallmark of neo-liberalism is precisely the idea of there being ‘no alternatives’), these processes will have influenced their values and behaviour to an even greater extent.

4. Exploring the Psychological Impacts of Neo-Liberalism on Youth Political Engagement

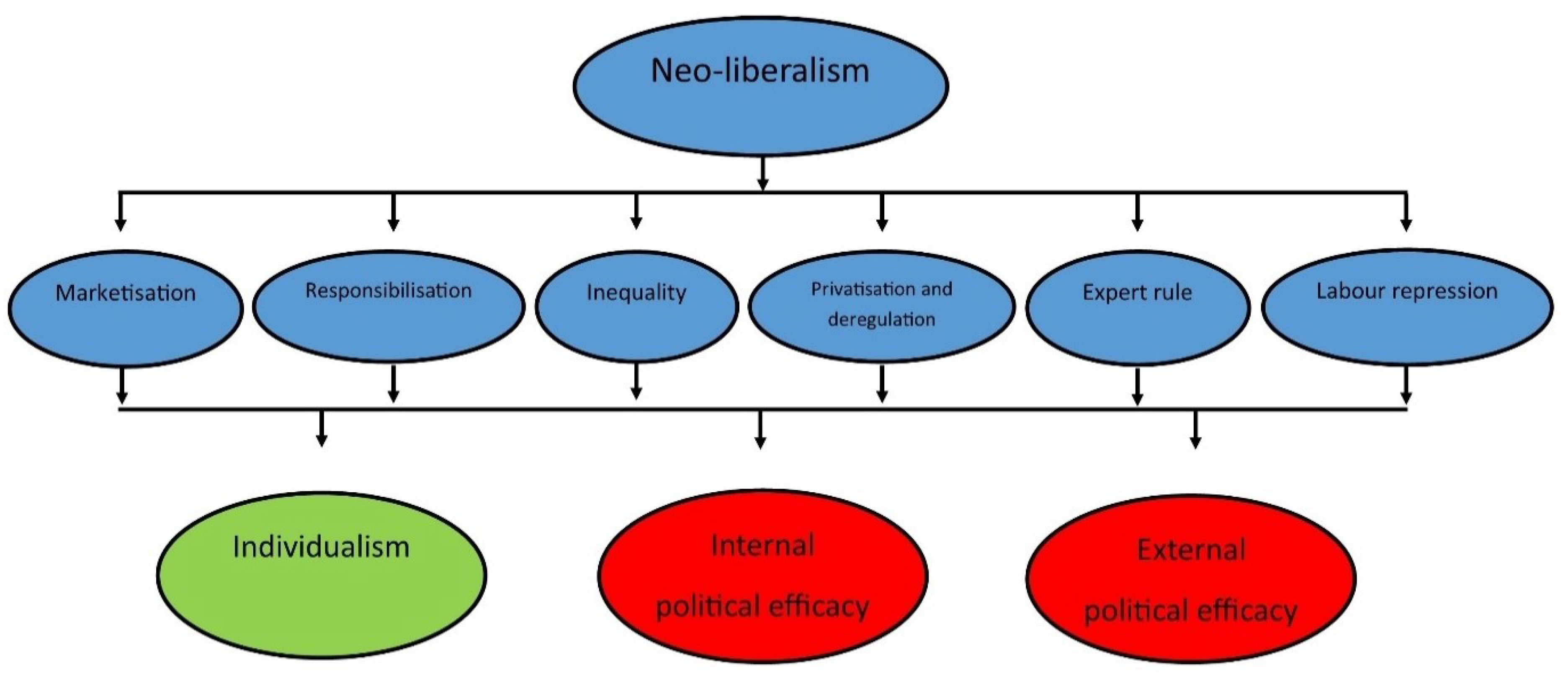

There are a number of theoretical and political critiques of neo-liberalism, and there is a considerable body of research on the effects of some of its impacts pertinent to political engagement. This article proposes that it is possible to summarise these into six broad impacts of neo-liberal policy, and further argues that these impacts, on an individual, subjective level, are experienced as increases in individualism and declines in internal and external political efficacy (see

Figure 1). How exactly to conceptualise and measure individualism is a subject of some debate within the psychological literature. However, it can broadly be defined as a ‘higher-order’ psychological trait, one that encompasses a number of other traits such as competitiveness, self-reliance and a preference for pursuing personal goals, rather than subordinating them to collective ones, amongst others [

57]. Political efficacy is often split into internal political efficacy (IPE) and external political efficacy (EPE). IPE is concerned with an individual’s own judgements regarding their ability to act in the political realm, whereas EPE primarily concerns an individual’s judgements regarding the responsiveness of the political system [

58,

59]. Measurements of IPE typically ask questions around whether an individual feels confident in their ability or skills to engage in political activities or discourse, whereas EPE measures will ask questions around their views on politicians, political parties, the political system as a whole or their views on political change. In essence, low levels of one or both types of efficacy can leave an individual feeling politically powerless, unable either through their own actions or through an unresponsive or ineffective state, to be able to affect change. Political efficacy has been well documented to play a role in political engagement [

59,

60,

61], although Wollman and Stouder suggest that situation-specific efficacy (efficacy over a specific political act) is a more useful predictor [

62]. Having defined neo-liberalism above, this article will now turn to exploring its key effects, and how, through these psychological impacts, it has potentially affected youth political engagement.

4.1. Marketisation

The first of these impacts is that of marketisation—the process of creating market or market-like systems where they did not previously exist. This process does not always require the direct creation of markets [

47,

63], but can proceed instead by fostering ‘market rationality’, in spheres that previously operated according to other rules or principles (the substitution of collectivism, or centralised decision making for individual responsibility, choice and competition). The aim is to economize increasing numbers of spheres of human activity, so actors act as if they were in a market even if an explicit market has not been created yet—the principles under which markets operate and the outcomes they achieve are seen as superior forms of organising human activity. This can be viewed as an explicit, possibly

the explicit, goal of neo-liberalism.

There is a significant critical literature on marketisation under New Labour. Key figures in the party often viewed citizens as ‘citizen-consumers’ [

64,

65], with consumerism a key way in which New Labour conceived of citizen activity. Rather than, say, active involvement by citizens in debates about how public or private services ought to be run, individuals were to be ‘empowered’ as consumers of public services [

66] (p. 449), very much along the lines set out by John Major when launching the Conservative’s Citizen’s Charter in 1991. As with this initiative, it was believed that it was through greater consumer choice that public services would be improved. Blair and other leading New Labour figures, such as Gordon Brown and Philip Gould [

67,

68], were concerned with ‘rebranding’ the ‘progressive political project’ and with the need ‘to build more diverse, individually tailored services…around the needs of the modern consumer’ [

69] (pp. 7–8). New Labour sought to expand the reach of ‘choice’ and ‘voice’ to citizens as consumers of public services, both of which are problematic notions. For example, choice can be seen as a mask for increased ‘marketization and/or privatization of public services’ [

66] (p. 450). Moreover, for New Labour, ‘bad choices’ made by citizens were due not to ‘the structural distribution of resources, capacities and opportunities’ but rather their own ‘irresponsible’ behaviour [

66] (p. 451). Voice can manifest itself in forms of tokenism, with consultation exercises ‘disconnected from consequences or outcomes’ making it very hard for those consulted to see how effective their and other citizens’ input has been [

66] (p. 450).

This is a process that has been particularly prevalent in young people’s lives—institutions they are likely to interact with during their formative years have been particular sites of marketisation under the neo-liberal project. Prime among these is higher education, which has been undergoing a programme of marketisation for a number of decades, but which has been particularly marked since 2010, altering the relationship students have with the academy to one of a customer, purchasing a product. In particular, universities have become sites whereby one enhances one’s ‘human capital’ in order to increase one’s competitiveness in the global, flexible, jobs market, most evident through the employability agenda ubiquitous across campus life now [

70]. Marketisation has also reached into spheres relevant to young people in the form of social work and child protection [

71,

72].

There is a tension both in values and in identities between citizens and consumers. As Kyroglou and Henn put it: ‘The former are defined as individuals who have the obligation to fulfil certain civil duties in connection to the government, in order to guarantee their rights and privileges. By way of contrast, consumers are instead perceived as merely preoccupied with satisfying their private material needs and desires’ [

73]. Lewis, Inthorn and Wahl-Jorgensen go even further: ‘Citizens are actively involved in the shaping of society and the making of history: consumers simply choose between the products on display’ [

74] (p. 6). They argue that media discourse and portrayal of politics and citizens reduces the citizen to a broadly passive consumer of political events, watching and occasionally reacting to events conducted by political elites. Here then we see that consumerism can foster more individualistic and also more passive relationships to politics and social change than citizenship. If young people are increasingly approaching politics and social change as consumers, rather than citizens, then there is a danger of frustration with the complex, negotiated process that is democracy, which must be engaged with ‘without any guarantee of satisfaction with the result’, as Hart and Henn put it [

75]. Indeed, prominent critic of neo-liberalism, Wendy Brown, argues we are already there: ‘[neo-liberalism] reduces political citizenship to an unprecedented degree of passivity and political complacency…The body politic ceases to be a body but is rather a group of individual entrepreneurs and consumers’ [

42] (pp. 42–43). For Streeck, these tensions go to the heart of capitalism itself. For him, democracy and capitalism are ultimately based on conflicting values, democracy emphasising citizen rights and social need, whereas capitalism is rooted in private property rights and ‘merit’, measured by work or input into the market [

46]. At their heart, then, markets are rooted in a more individualistic preoccupation with private property rights and commodity exchanges based on self-maximisation, whereas democracies, at least in the tradition of the Western welfare state model, inherently involve compromise, collectivism and

some degree of public, central decision making and ownership. The impact of increasing marketisation under neo-liberalism then has potentially been to make our identities as consumers more salient, in more spheres of activity than previously, increasing individualism and upsetting democratic citizenship norms and understandings.

4.2. Responsibilisation

Our second impact is the rise of ‘responsibilisation’, defined by the Sage Dictionary (undated) as ‘the process whereby subjects are rendered individually responsible for a task which previously would have been the duty of another—usually a state agency—or would not have been recognized as a responsibility at all’, designating it a ‘neo-liberal strategy’ [

76]. Lister draws attention to a general trend over the past few decades which has seen successive governments arguing for the need for citizens to take increasing personal responsibility for their own individual educational, health and welfare needs [

77]. The language of individual ‘responsibility’ was prevalent during the years in which New Labour was in power in Britain (although, of course, it long predates New Labour in the discourse of policy-makers). As the key ‘third way’ thinker, Anthony Giddens argued that a major theme for New Labour was the linking of rights and responsibilities—that ‘no rights without responsibilities’ was ‘a

prime motto for the new politics’ [

78] (p. 65, emphasis in original). The then Prime Minister, Tony Blair, argued that: ‘A modern notion of citizenship gives rights but demands obligations, shows respect but wants it back, grants opportunity but insists on responsibility’ [

79] (p. 218) [

80]. The model citizen, for New Labour, was shaped by various responsibilisation ‘processes’ [

66] (p. 451), with the party ‘seeking to create subjects who understand themselves as responsible and independent agents’ [

66] (p. 452). New Labour replaced unemployment benefits with a conditional jobseekers’ allowance, brought in compulsory workfare or ‘welfare-to-work’ programmes, abolished student grants and introduced student tuition and top-up fees. As Lister says, this trend has seen, among other things, the intensification of the conditions attached to receipt of benefits to various groups, as well as an increase in sanctions for failure to comply and the extension of conditionality to groups such as lone parents, partners and people with disabilities [

77] (p. 69).

This ‘responsibilisation’ agenda has strongly impacted on young people. For example, university tuition fees trebled in 2006 and again in 2010, and an even greater emphasis has been placed on young people engaging in voluntary and charitable work, under the banner of the ‘big society’ initiative [

81,

82] and the National Citizen Service programme [

83]. Moreover, this agenda can also be seen in the revised and slimmed-down citizenship curriculum in England, in which there has been a shift away from a focus on understanding political concepts and civic and political participation towards constitutional history and financial literacy, and an even greater emphasis on volunteering [

84]. At the same time, a form of moral education known as ‘character education’ has risen in importance on the political agenda in Britain. The understanding of character education put forward by British politicians has been narrow and instrumental, seeking to develop in young people various character traits, such as ‘grit’ and ‘resilience’, and linking this with individual ‘success’, in particular, in the jobs market, reflecting the government’s focus on pupils and students as future workers and consumers in a competitive global economy [

85,

86]. The clear emphasis in character education is on personal, rather than public ethics, and with addressing various important moral or political issues at the level of the individual rather than at any other level, thereby failing to address structural inequalities and placing sole responsibility on individuals for their position in society [

84].

This process extends beyond simply reforming welfare services or education, however. Under neo-liberal mentality, individuals’ subjectivity is radically altered: They are taught to be ‘small enterprises’, having to view their labour as a product, themselves as ‘human capital’, as strategizing entities working towards life goals by investing and gaining skills. Neo-liberalism ‘deploys means’ to govern individuals so that they really do begin to act in this self-maximising, competitive, risk-taking way, taking ‘full responsibility’ for their failures, increasingly ‘instrumentalising’ relations with others, ‘to the detriment of all other possible ways of relating to others’, damaging social bonds and relations [

40] (p. 280). Whilst such a narrative could be seen as empowering, it ignores structural constraints on individual agency—the impact of the way society distributes resources and opportunities. What happens when an individual ‘fails’ according to the discourse of responsibilisation? Indeed, some have argued that such a culture has led to a proliferation of mental health problems in neo-liberal society, with feelings of inadequacy or stress becoming common in these hyper-competitive, highly individualised and responsibilised environments [

87]. As Davies puts it: ‘One contradiction of neo-liberalism is that it demands levels of enthusiasm, energy and hope whose conditions it destroys through insecurity, powerlessness and the valorization of unattainable ego ideals via advertising’ [

63]. Others have also argued that the responsibilisation narrative, particularly in regard to welfare services, can undermine our sense of citizenship and our relationship with the state [

88]. At its heart then, this is a process of individualising risk and responsibility, making citizens think and act more as competing individuals, unreliant on mutual aid and also undermining a belief that government or other forms of collective provision could, or indeed even should, be responsive to citizens’ needs (external political efficacy).

4.3. Inequality

Our third impact relates to the dramatic rise in economic inequality witnessed both in the UK and globally since the rise of neo-liberal policy in the late 1970s [

89,

90], leading to a situation where: ‘Since 2015, more than half of this wealth has been in the hands of the richest 1% of people. At the very top … collectively the richest eight individuals have a net wealth of

$426bn, which is the same as the net wealth of the bottom half of humanity’ [

91]. In the UK, the bottom fifth of earners own only 8% of the income in the country, whilst the top fifth ‘earn’ around 40% [

92]. For wealth, the picture is even worse. The bottom fifth own close to 0% of the wealth in the country (wealth can indeed be negative, given the prevalence of private debt in many countries, including the UK) whilst the top fifth own 45% of all wealth in the UK [

92]. The Trust’s data also highlights that inequality rose from the 70s onwards, albeit at a declining rate since the 90s and with some minor declines in recent years. Stiglitz argues that key contributors to this rise in inequality have been financial deregulation and the decline of trade unions, both core tenants of neo-liberal policy [

89]. Indeed, some, such as Harvey, go as far as to argue that rising inequality is a

deliberate goal of neo-liberalism, that: ‘The distribution of income and of wealth between capital and labour

has to be lopsided if capital is to be reproduced…Workers

must be dispossessed of ownership and control over their means of production if they are to be forced into wage labour in order to live’ [

43] (pp. 171–172, emphasis ours). Aside from a class-based analysis of neo-liberal mentality, as Davies points out, inequality is the inevitable result of a system that prizes competition—there will be winners and losers [

48] (p. 30). There are normative logics at work here that justify this lopsided wealth distribution in neo-liberal mentality: ‘In turn, inequality is considered as a virtuous premium for the generation of wealth, which is destined to trickle-down to all members of the economy. In contrast, any egalitarian effort is not only counter-productive, but also morally repugnant, since the free market will grant everyone what they deserve according to their individual contribution to the economy’ [

73]. So, not only do neo-liberal policies foster inequality directly, but also malign policy aimed at redistributing this unevenness.

A number of studies demonstrate a negative relationship between inequality and various forms of civic and political engagement [

93,

94,

95] (although for a more mixed review see Geys) [

96]. A possible explanation for how this works centres around the atomising nature of inequality. Inequality has been shown to be negatively correlated to levels of social trust [

97,

98] and ‘Agreeableness’, which is ‘concerned with attitudes and behaviours towards others including empathy, trust, altruism, and inclinations towards friendship and cooperation’ [

99] (p. 1979). Armingeon and Schädel suggest that disadvantaged groups rely on cues from relevant social groups more when it comes to decisions such as voting [

100]. In their formulation, a fragmented social fabric therefore disproportionately impacts disadvantaged groups in terms of electoral participation—with weaker group ties, they are able to gauge these cues less easily, and therefore many stay away from the polls. If inequality is harming social trust and related factors, then it could be this that is at least in part driving the lower levels of political engagement witnessed in more unequal countries by robbing disadvantaged groups of an important political resource. Being able to develop and rely less on social bonds and the supports and norm-signalling they provide could bolster the other individualistic trends described elsewhere in this article. Given that young people are more likely to be in precarious work conditions (i.e., a disadvantaged group—see the ‘labour repression’ section below), it seems possible that the negative effects of inequality on engagement are disproportionately harming younger people. In addition, the uneven political power granted by huge wealth disparities, and the negative impact of income inequality on equality of opportunity with regards to education and skills development and on economic growth [

90,

101], could also negatively impact on political efficacy. In summary, more unequal societies (such as ones dominated by neo-liberal policy) see lower levels of political engagement, and this is potentially being driven in part by a loss of social bonds, i.e., societies are becoming more atomised and individualistic, experiencing the corrosive aspects on both the economy and equal political power that wealth inequality generates.

4.4. Privatisation and Deregulation

The fourth impact of neo-liberal governmentality is the changing role of the state through privatisation and deregulation. Between 1979 and 1990 (when Thatcher left office), 40 state-owned businesses, worth £60 billion, were sold. These included utilities (such as telecoms, gas, water and electricity) and industry (including steel, aerospace and rail) [

102], and amongst the wave of deregulation the 1986 ‘Big Bang’ of deregulated finance stands out. Standing also highlights how privatisation has reached out to public space itself, with places previously under right of way laws, or chunks of urban space, now being bought up by private companies [

103]. This can lead to the physical spaces in which democracy and political engagement occurs being denied to the citizenry, with new owners at times banning protest and other forms of activism from those sites (protests being banned outside the London Assembly building, privately owned, is a good example). This belies the wider problem with privatisation and deregulation; it removes policy options from the table of democratic, collective decision making, undermining the capacity of governments.

The impacts of these processes can be felt on a local level too. Todd documents how in the 1980s privatisation became a barrier to ‘collective power’ in communities, with elected officials no longer calling the shots it could often be difficult for local residents to be able to address community problems [

104] (p. 328). These processes can also reduce citizens’ access to facilities such as libraries and public service broadcasting that can help develop skills crucial to political engagement, potentially undermining internal political efficacy too [

103]. Recent austerity under first the Coalition and then the Conservative governments, partly borne out through privatisation and/or marketisation of services, has been shown to disproportionately fall on younger generations in particular [

52,

53]. The (party political) consensus (until recently) that seems to have formed around these ideas has also been theorised to relate directly to political participation, as there is simply less scope for change directly through the major political parties [

46]. Indeed, polling by Survation found this lack of a sense of difference between parties a key reason for citizens not turning out to vote in the 2010 general election [

105]. Privatisation can to some extent lock in this consensus by simply taking areas of policy completely out of the hands of future and opposition politicians.

As the capacities of, and belief in, government appear to decline, as more and more functions and responsibilities of the state are farmed out to private sources, businesses come to be seen as more and more relevant to citizens’ lives, and more viable vehicles for addressing their needs and wants [

73]. From the opposite direction, this ties into an increasing tendency, documented by Klein, of corporations (she singles out the likes of Nike) to increasingly sell not individual products but a lifestyle, increasingly encroaching into the cultural life of citizens and performing acts of charity or support that were once part of government provision [

106]. This is but a part of the wider goal of neo-liberal rationality, of subordination of the public to the private, and collective, solidaristic logics to those of market-like, competitive ones [

40]. It is important to note here that we are not advocating the simplistic and misguided view of neo-liberalism as invoking simple binary divisions between state and market—we recognise, as noted above, that the state is used to further advance market or market-like processes into increasing spheres of life, and that neo-liberalism is not about a simple stripping back of the state. Our contention, however, is that the states relevance to citizen’s lives, in terms of welfare, education or health, is severely curtailed under neo-liberal governance, whilst that of private providers grows. It appears then that privatisation and deregulation could be impacting political engagement both by transferring areas of policy from public into private hands (directly limiting the range of options for democratic expression), but also undermining faith in the capacity of collective institutions—a decline in external political efficacy, and potentially, by restricting citizens’ access to important resources needed to develop political skills, internal political efficacy too.

4.5. Expert Rule

Our fifth impact is the rise of ‘expert rule’, which Earle, Moran and Ward-Perkins describe as stemming from the dominance of a certain approach to economics, which they describe as ‘neoclassical’ [

107]. It is important to note that neoclassical economics should not be conflated with neo-liberalism, but in our view the tendency they are discussing applies also to neo-liberal forms of economic organisation. Neoclassical economics is an approach that views economic matters as primarily quantifiable and mechanistic, markets as broadly self-correcting and humans as ‘rational optimisers’. Earle, Moran and Ward-Perkins argue that such an approach has led to economic decisions increasingly being made by ‘experts’, as macroeconomic decisions are seen to have simple, evidence-based answers, thereby excluding the public from much of the realm of politics [

107]. Recall Davies’ (quoted earlier) contention that neo-liberalism aims to reduce the ambiguity and contestation inherent in political discourse to simpler economic issues. In this he also highlights the important role ‘economic policy experts and advisers’ come to play in neo-liberal governance; using the analysis of coaches in sport, he argues that ‘constructed’ competitive systems require experts to make the rules [

48] (p. 29). Peck, Theodore and Brenner, in discussing the diffusion of neo-liberalism, argue that it comes about via ‘fast policy’ processes that are often technocratic and advanced via calls for ‘best practice’, often with significant involvement of ‘experts’, and which ignore local contexts [

50]. This can foster a tension with democracy and engagement. As Hart and Henn put it, ‘politicians devolve the provision of services to politically autonomous agents (such as Quangos), while simultaneously resisting any collective requests of the electorate that seek reform of public provision outside of pre-established boundaries’ [

75].

In addition, under neo-liberal rationality, states increasingly act as commercial providers themselves. They become subsumed by concerns over performance and efficiency, increasing the role given to ‘experts’, rather than political, social or even democratic concerns [

40], and come to operate more along the lines of a ‘nomocracy’, which aims to develop a ‘rule-governed order’ that enables individuals to pursue their own private interests (in this case, through market or market-like systems), rather than a state-directed pursuance of collective goals (such as equality), as the purpose of law [

108]. It is easy to see how such an approach could favour technical economic and legal knowledge over and above the values and priorities of citizens. This happens in two ways: First, through obvious restrictions in democracy, whereby collective decision making is replaced with direct expert decisions, but also, second, by engendering a culture in which the ordinary citizen does not feel qualified to engage in political debate and is often left alienated and disillusioned by political discourse predominantly in the language of academic economics. Earle, Moran and Ward-Perkins describe such an effect as a ‘devaluation of citizenship’ and argue that it serves to narrow policy debates and, through a technical, knowledge-based discourse, reduce the sense citizens have of being able to participate [

107].

Examples of this in a UK context include the New Labour decision to make the Bank of England ‘independent’ and the Private Finance Initiatives scheme, which is a partnership between government and private companies to deliver public services and/or infrastructure projects [

109]. This formed part of New Labour’s attempt to develop policy-making on the basis of ‘what works’ rather than political ideology, which was problematic in various ways, being managerialist and technocratic, and seeking to depoliticise some policy decisions. Experts, broadly defined, often play a key role in disseminating policy-relevant ideas [

110]. In a British context, for example, the development of Thatcherite ideas was supported by free market think tanks, such as the Institute of Economic Affairs, the Adam Smith Institute and the Centre for Policy Studies—the impact of which on young people can be seen in the forms of marketisation and privatisation introduced by successive governments and the high levels of economic inequality set out above. The most recent trebling of university tuition fees occurred following the publication of the report of the Browne Review Group [

111], which in 2010 recommended removing the cap on the level of fees that universities can charge—a group that had among its members various ‘experts’, such as a former Treasury economist, a couple of Vice Chancellors and an advisor to former Labour Education Secretary David Blunkett. The coalition government followed many of the Browne Review’s recommendations but proposed an absolute cap on fees of £9000 per year. In their book analysing various policy ‘blunders’ in Britain, King and Crewe [

112] (pp. 405–406) make clear their view that the increase in tuition fees should be seen as one such blunder, questioning how many of the loans will ultimately be repaid, which could lead to greater rather than reduced government expenditure (although Crewe was a vociferous supporter when Vice Chancellor at the University of Essex of Labour’s trebling of tuition fees, having introduced them in 1998, from £1000 to £3000 per year, which came into force in 2006) [

113,

114].

As an example of what the effects of expert rule might look like for individuals, Condor and Gibson, in their study of the tensions between liberalism and democracy, discuss one of their respondents repeatedly refusing to answer a question concerning their opinion on the Iraq War, consistently citing their ‘friend studying politics’ as a better person to ask, even in the face of the interviewer telling them they just wanted their opinion and that there ‘wasn’t a right or wrong answer’ [

115]—a deification of ‘expertise’ to the point where political opinion not supported by an academic qualification is seen as illegitimate. Expert rule then, through an exclusionary political discourse and a narrowing of policy decisions, could potentially be reducing internal and external efficacy for the neo-liberal subject, and thereby reducing political engagement too.

4.6. Labour Repression

The final impact is the repression of labour. This is most obvious with the hostile environment trade unions faced under the Thatcher governments, which the Trade Union Congress (TUC) website details as a series of Bills throughout the 1980s and 1990s that ‘cumulatively, greatly restricted and controlled trade union activity’ [

116]. The TUC site goes on to argue that the impact of these reforms was to make it harder for unions to respond quickly and effectively to issues, and to increase their financial costs, and indeed, trade union membership in the UK has halved since 1979 levels, with younger people being significantly less likely to be a member of a union too [

11]. Mason argues that this process is key to neo-liberalism, as it needs to produce ‘the individualised worker and consumer, creating themselves anew as ‘human capital’ every morning and competing ferociously with each other’ [

117] (p. 24). Trade unions, then, are seen as challengers to market logics—pockets of collectivism that directly disrupt the idea of individuals operating in markets through commodified transactions. Under neo-liberalism, they must be defanged. This open hostility between two conceptions of social organisation is explicit in Thatcher’s own rhetoric on the miner’s strikes: ‘We had to fight the enemy without in the Falklands. We always have to be aware of the enemy within, which is much more difficult to fight and more dangerous to liberty’ [

118].

The changes to conditions for labour in the UK extends beyond a challenging environment for trade unions, however. Standing estimates that about a quarter of the population in the UK now falls into the category of ‘precarious’ worker (needing to engage with insecure labour to live, having to take pretty much whatever is offered) [

119]. He argues that this labour ‘flexibility’ erodes ‘relational and peer-group interaction’ [

119] (p. 23), that commodification has seeped into every facet of citizens’ lives, that it leaves citizens with no agency, ‘no capacity to resist’ market forces [

119] (p. 26), and that it can confound the ability to think long-term, to contemplate the past and present and link it to an imagined future. Hardgrove, McDowell and Rootham, through their qualitative interviews with young men in precarious employment, also highlight the temporary nature of such work, how in some jobs a worker can be given as little as half an hour’s notice to turn up to a shift or be fired almost at will, suggesting this transitory, uncertain existence particularly afflicts younger people [

120]. Indeed, evidence suggests that, overall, young people are ‘markedly over-represented among zero hours contracts and temporary workers’ [

121].

The ability to develop strong bonds or to plan and organise for work-based demands is severely challenged by such a process. The relationship between trade union decline and precarious work conditions is likely to be cyclical, with the decline of unions opening the door to loss of rights and good conditions at work, which have in turn fostered a more difficult terrain for union activists to recruit and organise. The decline of unions has also been linked to rising inequality [

89], something which also leads to social fragmentation, as explored above. It seems then that there are a number of things going on with this reduction in trade union activity and the changes in the nature of work. The obvious and immediate barriers to political engagement this creates, the challenge to a source of collective organising, often supplanted by pay and conditions being organised on an individual basis instead (which feeds into responsibilisation narratives explored above), and the lack of space and time to build the required social bonds and trust to engage in activism. Again, it appears these changes may be increasing individualism, and reducing external political efficacy, and given that they are less likely to be unionised and more likely to be in a form of precarious employment, it seems that this is affecting younger generations disproportionately, especially when many of them will be entering into the workforce having no memories of any other workplace landscape or memories of strongly unionised workplaces with stronger levels of social solidarity.

The impacts summarised above are, in many cases, interconnected and mutually reinforcing. As well as the decline of trade unions, deregulation, for instance, has been linked to increasing inequality [

89]. Privatisation has, in turn, also been linked to inequality in a mutually reinforcing way, whereby tax breaks for the rich (a partial driver of inequality) justifies ‘austerity’, which includes privatisation, and which hugely benefits the wealthy who buy up the previously public goods (sometimes at below market-valuations) [

90]. Responsibilisation narratives tie into more individualistic, competitive, self-reliant approaches to work that are likely both cause and consequence of declining union membership and collectivist solidarity more generally. Pervading them all, we argue, is a subjective experience for the neo-liberal subject that is characterised by increasing individualism and declining levels of political efficacy. This is likely to have drawn individuals away from collective forms of organising and political expression, such as political parties and trade unionism, and away from engagement with traditional politics, such as voting (all of which is born out in the trends in engagement presented above). Given neo-liberalism’s emphasis on, and empowerment of, the market, and the fostering of more individualistic, consumerist identities, it is possible that individuals find some limited form of political expression through political consumerism; that the market becomes the site of political contestation under neo-liberal subjectivity. This potentially explains what we are seeing with the rise of political consumerism described above.

5. Political Consumerism: Switching to the Market?

There has been a great deal of research in recent years into the prevalence of political consumerism, and the characteristics of those that engage with it, which has thrown up a number of issues. Prime among these is the relationship political consumerism shares with other forms of engagement. Newman and Bartels data suggests that political consumption takes place alongside acts such as voting and protesting [

20], yet we know over the time period political consumption is reported to have risen formal engagement has declined, so how can the two be squared? The alternative, of course, is that as citizens become disillusioned with traditional political institutions, the market increasingly becomes the site of political expression and contestation. Indeed, in the same study Newman and Bartels found political consumerism to share a negative correlation with trust in political institutions [

20]. Just as its relationship with other forms of engagement is little understood, so too is its relationship with neo-liberal values. Neilson and Paxton found political consumerism to be positively correlated with social capital, contrary to the theory presented above [

122]. A potential solution comes from Gotlieb and Wells, who suggest that the link between political consumerism and more conventional forms of political engagement (if it exists) is mediated by a ‘collectivist’ orientation to political consumerism; holding a shared identity and goals with other consumers made political consumers more likely to also engage in conventional forms of political engagement too (interestingly, the researchers only found this orientation effect for younger generations, but not older ones) [

123].

How many citizens do engage in a more collectivist form of consumption is questionable, however. Newman and Bartels’ study also found that engaging in more individualised ‘checkbook’-style politics significantly increased one’s likelihood of engaging in political consumerism [

20]. In referring to her quadrant system of different motivations behind political consumerism, Atkinson states, ‘those political consumers on the side of negative rights who see benefits from a lack of government intervention would probably find little common ground with those on the positive rights side of the map who welcome government regulation as a means to guarantee the welfare of others and the health of the environment. Surveys would lump these two groups together when, in fact, they might have less in common in their beliefs about rights than a quantitative analysis would imply’ [

124] (p. 2061). Perhaps, then,

some individuals who engage in political consumerism maintain collectivist orientations and express these through traditional engagement in conjunction with political consumerism, explaining the correlation between the two types of engagement. There might be another group of political consumers, however, who are losing political efficacy and increasing in individualism and, therefore, are abandoning traditional/collectivist forms of engagement for political consumerism.

6. Conclusions

This article represents an initial attempt to analyse neo-liberalism’s effects on citizens’ individual subjective experiences. It had two main aims. First, to convince a wider group of researchers that the ideology or, as we prefer, ‘governmentality’ of neo-liberalism is worthy of scholarly study in relation to youth political engagement; and, second, to suggest a direction for future research that is rooted in observable, measurable phenomena, moving scholarly study on beyond theoretical critiques (important as these are) to an analysis grounded in empirical evidence. It has sought to provide an agenda for exploring the psychological impacts of neo-liberalism on youth political engagement; a rough map to guide future work in this area. This has been done in two ways: First, a general approach to broader analysis of political engagement trends that includes summarising existing critiques of neo-liberalism (but could equally be done for other governmentalities or ideologies too) into key themes or impacts, and then exploring the literature into these impacts, summarising these again into observable, concrete psychological influences that can then be linked to political engagement, developing a causal chain from political ideology to individual political behaviour. Secondly, this article has argued that, as a result of this process, the primary psychological effects that define the personal experience of neo-liberal policy are declines in internal and external political efficacy and an increase in individualism, and that this is particularly pertinent for younger people. It is then in understanding the relationships between these factors, and others (such as forms of ‘consumer efficacy’ and business trust), that we can begin to understand the real impacts of neo-liberalism on youth political engagement, in a way grounded in empirical work and nuanced theory. This links well with work undertaken by a variety of authors who have utilised the concept of governmentality to examine the operation of liberal and neo-liberal forms of government and its effects on the individual [

36,

125,

126]. The suggestion is not that that there are no other traits potentially pertinent to the subjectivity experienced under neo-liberalism. On the contrary, we would anticipate that future research may well reveal other psychological factors that should be incorporated into the model. Future work could utilise this Foucauldian framework to further explore the connections between neo-liberalism and youth political engagement, drawing on specific changes to subjectivity described or alluded to in works that make use of this approach, using them as starting points in empirical research.

Neither has the argument presented in this article been that young people are apathetic, nor that they are selfish or self-obsessed, all of which have been associated with the idea of a more ‘individualistic’ generation. Rather, the argument is that neo-liberal politics has overtly shut down and subtly eroded faith in many forms of collective decision making, whilst also forcing many young people to have to engage with competitive and consumer-based tropes in an increasing number of spheres of their lives. This argument does not rely on the trope of young people being selfish, but simply contends that they are encountering higher education and work cultures that are more intensely marketized, and where they are consistently responsibilised, operating in a broader social context marked by extreme inequality and its attendant social fragmentation. This does not mean that a desire for social change is not still present, but that this can often take new forms and happen in new sites, such as more market-based activism that does not depend upon government change. Neither are we arguing that ‘we are all neo-liberals now’. We are arguing that discourses and policies that disparage or damage collective and traditional political institutions have led to changing political expression and changing psychologies, not that everyone now supports market systems and expert invasion of politics consciously and explicitly.

Recent political events also need to be considered within this research framework. The much debated ‘youthquake’ could be an important turning point for youth engagement in the UK. The Corbyn movement is one that has explicitly rejected neo-liberal thinking and embraced forms of organising and discourse somewhat contradictory to its logics. It is possible that what we are witnessing is a generation fed up with the injustices reaped upon them by the imposition of neo-liberal policy turning to a movement explicitly rejecting this form of governing. Whether this will be successful or sustainable in light of the wide-reaching changes to both policy and psychology under neo-liberal rationality remains to be seen. Neo-liberalism has contributed to a deep aversion to traditional politics, especially amongst younger generations, and this may be difficult for new left-wing movements like Corbyn’s to overcome. Equally, it potentially poses challenges for the neo-liberal project itself—to the extent that it still requires legitimisation through democratic processes (although with privatisation and expert rule, this is questionable), it may be undermining its own further extension.