Abstract

Imagined stereotypes of Roma are prevailing across Europe and have an impact of discrimination and social exclusion of the Roma. In 2011, Denmark published their National Roma Inclusion Strategy as a response to the Europe 2020 Growth Strategy. This study analyses how the Roma are represented in the national policy and in ongoing discourse regarding Roma in newspaper articles published around the time of the publication of the Strategy. A critical discourse analysis was conducted, and the findings show that a profound stigmatization of the Roma was common and acceptable in both Danish nationalistic media discourse and in the paternalistic policy discourse. The Roma were represented as an alienated, non-empowered group in contrast to the majority population and lacking any useful qualities. There was a lack of Roma voices in both policy and newspapers. The discourses regarding Roma in Denmark are lacking both Roma influence and initiatives to change Roma conditions.

1. Introduction

The Roma people have been living in Denmark since 1500. Their past and present have mostly been characterized by persecution and alienation from the main population [1]. Stigma and social exclusion towards the Roma is still an ongoing phenomenon in many European states including the Nordic countries [2,3,4]. Social exclusion is one of the main causes of health inequalities among minorities and migrants including Roma [3]. Furthermore, the stigmatized Roma are often the subject of negative discourse in media and political debate [5].

The conditions of the Roma people have been the interest of the government and media throughout the years. Politically, the Nordic countries have different ways of approaching the Roma population. Whereas Sweden has recognized Roma people as a minority since 2000 [6], Denmark has yet to do so. Denmark joined the European Council’s Framework Convention on the protection of national minorities in 1997. Since then, the European Committee of Ministers has criticized Denmark for not including the Roma as a national minority [1]. The European Commission launched the EU Framework for Roma Inclusion (FRI) in 2010. The goals of the FRI focus on providing the Roma population with better access to four key areas: education, housing, employment, and healthcare [7]. The FRI is a part of the Europe 2020 Growth Strategy, which has four main objectives: education, employment, innovation, and climate [8]. The FRI is a recommendation to all member states and thereby not legally binding. The European Commission evaluates the national policies annually. The improvement process on Roma conditions is set on a large political scale, but the implementation processes in the member states are of various success. In several Nordic countries, specific interventions have been initiated in order to improve Roma inclusion, although not all with complete success [9].

In 2011, the Danish government published the first National Roma Inclusion Strategy [10]. An opinion poll (Eurobarometer) from 2012 showed that only 3% of respondents thought that the current effort to improve integration of Roma had “great affect”, whereas 59% perceived that it had “no effect” [11]. Research on how the media affects the political agenda is ongoing. A review states that media plays a contingent part in the policy agenda setting [12]. Public policy often reflects movements, opinions and moods of the main society, and the prevailing themes of the public discourse may influence the content and implementation of the public policies [5]. However, the debate in the daily press is often dominated by topics and actors that represent the majority of the population and ignoring the voice of the minorities in question [13,14]. Policymakers often regard formal representation structures to be adequate opportunities for participation. However, minorities, such as the Roma, often require more structural support than the majority to be influential [15]. Ter Wal’s report on racism and cultural diversity in mass media even showed that the media performed subtle racism toward immigrants [15]. Some of the criticism made by Ter Wal was that journalists did not question statements regarding minorities pronounced by members of a political and cultural elite. However, members of a minority were confronted with critical questions [15]. The Eurobarometer opinion poll in Denmark from 2012 showed that 59% of respondents thought that Roma were in risk of being discriminated. When the respondents were asked how they would feel if their children had Roma schoolmates, 42% reported to be feeling “totally uncomfortable” [11]. The statistical data on the development of discrimination related to ethnic origin in Denmark in 2012 shows that 70% of the respondents perceived discrimination to be “widespread.” In a repeated measure in 2015 the corresponding figure had increased to 78% [16]. With regard to the Roma, recent media discourse has been characterized by “scandalous cases of the many Roma migrating to Denmark” and presented by the tabloid press [17]. Thus, the portrait of the Roma in the Danish press has mainly been negative.

The aim of this study is to investigate how Roma representation is formed in both the Danish Roma policy discourse and in the Danish media discourse and whether these discourses interact and affect wider social policy and practice. This paper seeks to provide a critical analysis of the policy intentions of integrating Roma in Denmark and of representation of Roma in the media in order to draw attention to the development of Roma social inclusion in Denmark.

The perspective of the study is rooted in the field of Public Health. The key concerns in this field are the social determinants of health [18] including social and economic inequality between population groups and geographic areas. Even though there is robust evidence witnessing inequalities in health and well-being across the world, many countries do not prioritize policies that would support action on the social determinants of health and equity [19]. (The term inequity refers to differences between people and populations that are not only unnecessary and avoidable but, in addition, are considered unfair and unjust [19].) The focus of policies and action to tackle inequalities should be on levelling up and reaching the vulnerable groups, such as Roma. Societal issues like lack of political influence, marginalization and discrimination lead to differences in access to resources and opportunities in life and have direct impact on population health and well-being.

2. Theoretical Perspectives Underpinning the Study

2.1. Critical Discourse Analysis

Critical discourse analysis is a theoretical perspective originated from social science, which has produced important insights into the nature of language and its role in contemporary societies. It has roots in social constructivism [20,21]. One of the key assumptions of social constructivism is that the people construct knowledge as members of a community or part of a particular context even though each person has his/her own world view that he/she believes in. These beliefs and world views are formed by culture and shaped or maintained through social practices. Even though in a social constructivist view knowledge and identities are considered to be contingent, the social situation is fixed and regulated [22].

Fairclough’s critical discourse analysis [21] unveils the relation between language and society and emphasizes the active role of discourse in constructing the social world. Fairclough bases his analysis on the theoretical foundations of Michel Foucault [23]. He defines discourse as a group of statements belonging in a discourse formation meaning that a discourse is set by a limited amount of statements for which you can define the conditions of possibility [24]. Foucault means that discourse has a distinctive and important role in the constitution and reproduction of power relations and social identities in a society [25]. Important in critical discourse analysis is analyzing text production and consumption and how these constitute social relations and identities [21]. Where Foucault views the concept of power as a productive mechanism, which runs through the society [23], Fairclough claims that discursive practices contribute to production and reproduction of unequal power relations between social groups. The critical discourse analysis’ purpose is to reveal this cause and determinacy relation between texts, discursive practices, and wider social structures [26].

2.2. Representation and Stereotyping in the Media

The discursive approach examines how language and representation produce meanings but also how the knowledge of a specific discourse connects with power, produces identities, and regulate conduct [27]. If discourse is served to establish practices (social and political), which keep certain groups away from resources, the discourse can be called racist according to Hall [28].

Hall refers to people being perceived as “the other,” different from majority of the society. In order to make sense of the world we assign people to certain groups according to gender, race, nationality, ethnicity, etc. However, “the other” is often given a fixed and simplified characterization which is not easy to change. They become a certain “type” [27]. Stuart Hall reflects upon the representable practice called stereotyping. Stereotyping is a way to keep social world into place by including those who behave according to the accepted norms and rules of a society (us) and excluding those who do not (them). Stereotyping is a form of symbolic violence where some objects are represented in a negative way and where the powerful representatives of the society use their power to “lock” these objects in certain characterizations [27].

Media plays a role in reproducing public discourse and provide input to people’s notion on ethnic groups by constantly re-imagining and re-constructing Roma as “the other” [5,29,30]. Minorities are not often actors themselves in the media, and minorities are often connected to topics like crime, violence, or strange cultural behavior [31]. The media does often not focus on the rights of immigrants but rather on their “wrongs” [31]. These are often concerns that have little relationship to the reality of the problems. They are, however, issues that raise public anxiety, called moral panic [32,33], in response to the problems presented by the media as threatening the moral standards of society.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Design

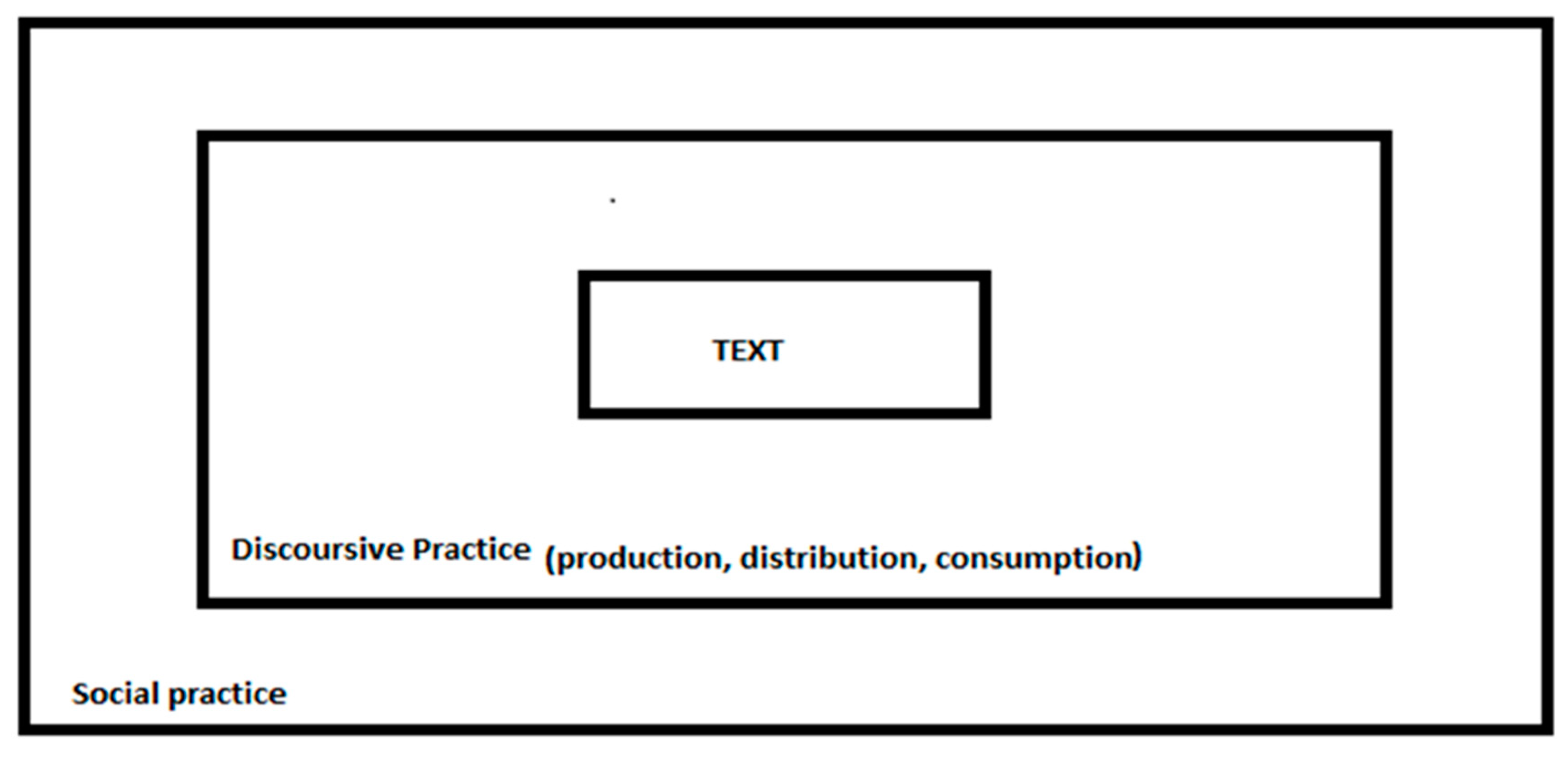

This study was conducted using Fairclough’s Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) [19,22]. The CDA method was chosen since the method is usable for various text materials and can reveal dominant discourses [34]. CDA can be argued to be an appropriate approach in analyzing complex policies and policymaking. It demands a fine-grained analysis of policy discourses and their production towards an analysis of the social context and their impacts on policy arenas [35]. Discourse is a part of social practice, which both reproduces and changes knowledge, identities, and relations and is a product of other social dimensions. Furthermore, Fairclough believed that critical discourse analysis can be used to draw attention to societal inequalities by changing knowledge and thereby power relations [20]. Thus, analyzing different texts will reveal dominant discourses and how people are represented in texts. However, these findings should always be approached critically, since it is the author who evokes these topics [21]. Fairclough’s discourse analysis includes three levels of analysis consisting of a linguistic analysis of the texts, an analysis of production and consumption in the discourse practice, and an analysis of the social practice, where the two aspects of text and discourse practice are placed in the wider social practice (Figure 1) [21].

Figure 1.

Discourse and social change by Fairclough.

3.2. Sample

Two types of documents are analyzed in this study: the Roma Inclusion Policy [10] published in 2011 and Danish newspaper articles from four different newspapers from the 1 January 2009 until 31 December 2012. The articles provided content with regard to the Roma living in Denmark. The four newspapers were chosen because they target a widespread readership and have the largest circulation figures [36]. The newspapers were Berlingske Tidende, Politiken, Morgenavisen Jyllandsposten and Ekstra Bladet. After perusal, 43 articles were selected and sorted according to topics and actors.

3.3. Data Analysis

A textual analysis was made of the policy document proceeded by an analysis of discourses and social practices of the Danish National Roma Inclusion Strategy and 43 newspaper articles. The purpose was to reveal distinct orders of discourse and actors in both newspaper publishing and policymaking, how policies and media interact with each other, and furthermore how they affect and are affected by social practice. The three dimensions of Fairclough’s framework overlap but are kept separate in the analysis [20,21]. Textual analysis has three main areas: vocabulary, grammar, and text structure. First, we performed textual analysis focusing on the choice of words/synonyms to see how opinions were expressed through these choices and how grammatical expression and text structure support the nature of both the inclusion strategy and newspaper articles. Textual analysis is a description of the text focusing on choice of words or statements that can reveal both hidden meaning and illustrate a political agenda [37]. Furthermore, textual analysis can reveal different types of discourses and any ideological struggles going on in the text. This textual dimension is closely connected with the second dimension called discourse practice. When we analyze a text, the work always engages in production and consumption processes, as they are closely connected. However, the two aspects are divided analytically [21]. We assumed that both text and discourse practice would reveal how they are formed and form the social worlds and how they are a contributing factor to secure specific interests and power relations.

The relationship between the social practice and the text is mediated through discursive practice. There is a dialectic between the three dimensions [37]. A social institution includes specific orders of discourse and of ideological norms [37]. The orders of discourse are composed by genre and discourses, whereas the genre both constitutes and is constituted by the specific use of phrases and words [21,38]. The analysis of the discourse practice reveals how authors use known genres and discourses and how readers interpret the text using former discourses [21,39].

To analyze social practice, Fairclough suggests a division of discursive and non-discursive elements. The social practice is the frame in which the text has been analyzed linguistically and as discourse practice. In addition to investigating the relationship between discourse practice and order of discourse, one should perform a mapping of the non-discursive social and cultural structures that form the framework [21]. In this framework made by social practice, it is seen whether discourse practice challenges the hegemonic and ideological dominance or is reproducing the order of discourse. Often, ideology is incorporated in the text as “common sense,” and the analysis identifies what lays behind it [38]. Ideology is put in relation to hegemony, as it is in struggles for hegemony that power relations are either changed or maintained. The ideology is discovered through the analysis on how different discourses represent people—in our case, the Roma. These results are, according to Fairclough, essential to make social change [40]. The question is how the discourses found in the texts are connected to the social dimension consisting of non-linguistic elements and what affected the discourses both in the newspaper articles and in the policy?

4. Results

4.1. Danish National Inclusion Policy

A political paternalistic discourse was identified in the Roma Inclusion Strategy from 2011 [10]. The strategy is in all aspects a political document revealing that the target group of the policy is not the subject of the document and reveals little affinity to the content. Consequently, the text refers to the Roma as a vulnerable group not capable of contributing to society in general, and they are constantly referred to as alienated (p. 8 [10]). This is furthermore emphasized by the use of the Roma in contrast to the Danes. This us/them duality is established throughout the document. The text seldom addresses Roma residents in Denmark, though many Roma are an integrated part of Danish society. The lack of information on the Roma becomes clear in the choice of words: “persons with a Roma background are estimated to have been relatively constant” (p. 2 [10]). This section is remarkably different to other statements, which are stated as factual and indisputable. In addition to this, it appears that in the first edition of the Inclusion Policy, the Roma were mentioned as nomadic. “Nomads” being a loaded synonym associated with solid stigma is not part the discourse genre of legislative or governmental text. This synonym was changed as was noted in the consultation response [41].

The Inclusion Strategy includes intertextuality as a solid component throughout the strategy in reference to policies already in practice or well-known key values in Danish legislation (human right being respected). The political paternalistic discourse is predominant when the text refers to the different existing policies (p. 9 [10]). The strategy determines that the existing policies meet any demands Roma inclusion would produce. Furthermore, the lack of information on Roma is mentioned to support reasons why no specific action is initiated to secure better Roma inclusion. The strategy even includes statements that are not elaborated. When describing the “Action Plan”, three targets are mentioned. The headline would indicate a plan for action or initiatives to be launched; however, the targets are descriptions of existing policies. The first three components are as follows: (1) Fully realizing the integration tools available for the benefit of Roma inclusion (p. 5 [10]). The description that follows is a summary of the key topics in the Integration Act and exclusively focusing on immigrants coming to Denmark; (2) Continuing and strengthening the efforts toward combating poverty and social exclusion in general. This paragraph contains a repetition of EU funds, which are included in the Growth Strategy but not particularly aimed at the Roma Integration Project; (3) Disseminating knowledge on best practices and agreed principles for Roma inclusion to the municipal level is not commented on. The strategy is dissimilar to other governmental interventions strategies; it is quite short and has no table of contents, logos or pictures. Compared to the responses from Finland and Sweden, the structure of the strategy is informal.

The social circumstances in which the strategy have different influences on the document. Even though the incitements to the strategy originated in the EU, their recommendations on targeting Roma more specifically in public policies are not followed [42]. The lack of acknowledgement of the recommendation on participation from the Roma society in Denmark is especially remarkable, and in general, not uncommon. Roma people are poorly represented actors on local and national political level all over Europe and have difficulty in participating in a policy making process on equal terms with the majority population [43,44,45]. A study in Sweden showed that in order to the Roma inclusion to succeed, Roma themselves should take a lead in this process [46].

In the summer of 2010, the Roma from Eastern Europe temporarily settled in parks and open spaces in Copenhagen. Local and national politicians expressed condemnation toward this Roma immigration, and they were deported during the summer. The deportation was declared a violation of human rights in 2011. The incident is not mentioned directly in the strategy, although several times, it is stressed that the benefits of the Danish welfare system is for persons who are legal residents in Denmark (pp. 7,11,12 [10]). The analysis of the social practice indicates that the policy is produced within a short time span with little time for, e.g., relevant NGOs to make a consultation response, even though the recommendations from the EU. The few actors that did manage to respond had only a few or no corrections to the policy. In particular, actors with large administration had little time to respond. The Roma organizations that responded suggested that the policy should be translated into Romani language, but this suggestion was not met [41]. The paternalistic discourse is stated by representing the Roma as a vulnerable and an alienated group not seen as a full member of the Danish society. Thus, this is in line with Stuart Hall’s notion on seeing outsiders or people of ethnic minorities in opposition to main society [27].

4.2. Newspaper Articles

A nationalistic discourse becomes visible when analyzing the identified 43 articles. It is a surprisingly unilateral discourse in the four different newspapers in spite of a wide range of readers. The discourses are consistent with the way the National Inclusion strategy [10] is representing the Roma: vulnerable and weak contributors to welfare. Alternatively, they are presented with synonyms as difficult guests [47], illegal immigrants [48], and an European challenge [49]. Ekstra Bladet exclusively used the discriminating word “gypsy” in their articles, staying true to being a populistic tabloid paper. The fierce stigma is supported both by choice of words and in the theme of the articles. The deportation cases and crime/poverty were the major topics.

The most graphic headlines were found in the tabloid paper, but the articles have the same textual structure with high affinity and an indisputable modality.

The strategy of an “us/them duality” was dominant to show the supremacy of the Danish state; the duality in the articles depicts the Roma as a stranger or an enemy, which supports a nationalistic discourse that has only few opponents. This unilateral discourse is supported by the fact that no Roma resident in Denmark is quoted or contributes to any of the 43 articles analyzed. This is similar to the findings of a Finnish study [50] showing that the main discourse had a nationalistic tone where Roma asylum seekers were portrayed hunting for the benefits of a welfare society. The few advocates for the Roma are non-Roma Danes. Most actors presented in the articles are politicians, law enforcement, or newspapers. The representation of the Roma is similar to the representation of the Roma laid out in the discourse of the Danish Roma strategy. As for other Roma people in Europe they are represented by non-Roma [43]. There is no challenging of the order of discourse in the newspapers. Even though Politiken, Berlingske Tidende, and Morgenavisen Jyllandsposten are politically independent [35], they are still constricted to a certain framework in their production of articles. Berlingske Tidende and Morgenavisen Jyllandsposten have liberal viewpoints, whereas Politiken has a multicultural expression. These newspapers often use textual structure to emphasize the importance of the article, whereas Ekstra Bladet has metaphors and adjective clauses, which are picturesque and often biased [51].

Whereas politicians use the deportation cases as a base for populistic statements inciting the hostility toward the Roma, the newspaper journalists use textual structure to note the opinion of the newspaper. Previous studies have shown that Politiken was that most impartial newspaper [15]. The major topic covered were the deportation cases and they were commented on in Politiken in an editorial when the supreme court found that Roma rights had been violated [52]. Morgenavisen Jyllandsposten did the opposite and stated that believing in the supreme court ruling would characterize you as being quixotic [53]. The two newspapers established their order of discourse and stayed true to their readers.

Journalism is not situated by itself but in relation to politics, media consumption, and an economical specter [54]. In the last 15 years, newspapers have been challenged on several fronts. Media consumption habits have changed rapidly during the last decade, and social media and small free papers now threaten traditional newspapers. They are dependent on advertisers who direct their advertisements to the readers of the paper. Furthermore, the internet-based approach to the news media is not only a platform for new readers but also demands short and fast context-based news, abandoning investigative journalism [55]. An analysis made in 1996 in Denmark on ethnic minorities and mass media showed that the topics covered on minorities regarded crime and asylum. It created a “moral panic” (a feeling of fear spread among a large number of people and often not based on reality, see e.g., [32,33]) and, increasingly, harsh statements about “second-generation immigrants” were voiced by politicians [15]. The unilateral discourse about the Roma in news media was criticized, but it is still an ongoing phenomenon, even though some initiatives for greater equality in the coverage of ethnic minorities were implemented in 2000 [15].

The difference in media coverage of the Roma cannot stand alone from public discourse or politicians who comment on the topic. The newspaper coverage of Roma issues and the National Roma strategy have similarities in the way they both reproduce former discourses and do not challenge power relations. This is supported by KhosraviNik’s study that showed that newspapers coverage, in spite political orientations, represent ethnic minorities in a similar way [56]. However, the media is an important political actor and sets the stage for other actors as well [13,45,57]. The deportation case is an example on how newspaper coverage causing a “moral panic” can influence policy making [32,33]. We believe, that to favor a much-criticized marginalized group who have few advocates does not resonate in public discourse and is an example on how public opinion affects policy making. Cohen states the same kind of situation when the British Government made harsh immigration initiatives in 2002 following persistent media coverage of illegal immigrants [58].

5. Discussion

The purpose of the Danish Roma Inclusion strategy [10] is to present Danish intentions on better Roma inclusion as Denmark is a member of the European Commission and has responsibility to act on recommendations [7]. However, the analysis of the discourse of the policy indicates that initiatives on Roma inclusion play a minor part on the political agenda. Despite recommendations from the European Commission, Roma influence on the strategy was insignificant. The lack of Roma participation is evident, as there are no statistical or qualitative data on Roma in Denmark that could have presented specific targets and main topics in an inclusion strategy. The fact that references to other social policies were a solid component throughout the strategy would support the assertion that policymakers consider these policies appropriate to cover Roma challenges. A study by Facchini and Mayda [59] showed that voters’ opinions are taken into account when making migrations policies. However, the lobbying of other actors could be also significant. The discourses are mainly paternalistic, stating no effort to further improve Roma inclusion, as the Danish welfare system is well functioning and minority rights are secured. There is, though, a call for clarifying the needs of this particular group in Denmark to give valuable and correct information on Roma.

Furthermore, the paternalistic discourse is prominent as core values, such as equality, in Danish society are stated as a defense of unspecific Roma targeting, but it is also visible in the recitation of social benefits for people who are legally residents in Denmark. The paternalistic discourse presents the Roma as a weak group not able to contribute to Danish society and as recipients of social benefits. Not only is the alienation of the Roma supported by terms and phrasings in the text, but also the involvement of actors is pointing at unilateral representation of the Roma. To secure the inclusion of the Roma in Denmark, the authors believe that there is a need for the recognition of Roma as a national minority. This recognition would allow the Roma access to the structural support needed to have influence on policies regarding their own situation and help them to be recognized as a natural part of Danish society. This would require legal action from Danish authorities to recognize the Roma as an ethnic minority in Denmark as other Nordic countries have already done.

We have established that the Roma are a small actor in the development of the Strategy. They have little influence on the content, and they are represented in a unilateral way, which is affected by the media. Other studies have confirmed that the media often have a great political role [31,59]. The representation of the Roma in the Strategy is similar to the one from the deportation cases from 2010. All in all, the Roma were characterized as a homogeneous group with the same characteristics and capabilities, which is consistent with similar findings in studies conducted in Finland on participation and representation by Haavisto [13]. Furthermore, the focus of the discourse shifted from the Roma residents in Denmark to foreign Roma residing illegally. The public debate often depicts the Roma as exploiting the welfare system, which would make promoting Roma inclusion a “wrong priority” in a political context [31].

Although the four newspapers chosen to the analysis are impartial, they are not apolitical [41]. Although they target a wider population than earlier, they still target certain types of voters [41]. In three of the newspapers, the discourses used in articles regarding Roma representation are characterized by uniformity and a generally negative image of the Roma. Ekstra Bladet is a tabloid paper where the perspective of the Roma is not nuanced, and the use of stigma is profound. In the other newspapers, the Roma are presented as a homogeneous and non-contributing group. The discriminative discourses are both present in phrasing and by the choice of topics. In the vast majority of the articles, the topics relate to crime or deportation cases. This duality is seen in another study [60] where Roma are represented as either a victim or a criminal. Roma social conditions are a salient topic in the newspaper media, but it is contradicted to the stereotyped image of Roma also significant in media coverage. The lack of Roma advocates in the public debate both in the newspapers and in public policy is remarkable. The few advocates for the Roma are not Roma themselves. In Finland, the lack of response was explained by illiteracy and poor tradition for newspaper reading among the Roma, making it difficult to participate in the public debate [13]. Since there is a lack of information and research data on Roma residing in Denmark, it is difficult to get a clear picture of Roma conditions. The Roma lack an active official organization in Denmark, which would create a channel to the public debate.

The mistrust the Roma often have towards society in general is reinforced by the prominent stigma they are subjected to, and it does not encourage further Roma participation. This could explain the lack of Roma voice in the public debate so far. The newspapers media coverage of the Roma is likewise characterized by the same discursivity as in the Roma Inclusion strategy, and none of the analyzed articles are challenging the views on the Roma in order to change such views. To change the profound oversimplified representation [61], the Roma people need a sizable and recognizable political voice and media presence to challenge the common understanding of the Roma. The future research and discourses on Roma minorities should recognize the nuanced diversity of the Roma minorities with additional variables, such as new patters of living, socio-economic and legal status, local and national contexts, immigration status and entitlements of restrictions of rights [61,62].

Limitations

The fact that the same method is used on two different types of public documents and with a widespread target group can be considered inadequate justification. However, critical discourse analysis is approved to be used on various types of documents [20]. Since it is the authors who evoke topics from the textual analysis, the analysis becomes subjective and must be taken into account. It is a fact that, when doing a discourse analysis, the analysis relies on the researchers’ reading and interpretation of the texts. We are fully aware of this possible bias and do not claim to have revealed any universal truth or neglect that our findings are context-based and observer-specific [63].

6. Conclusions

The conclusion is that a more nuanced image of the Roma in Denmark is needed. The steadfast representation of the Roma being a vulnerable and weak group stated by both authorities and media limits the chance of any social change for Roma in Denmark. The Roma are still a minority vaguely illuminated with few actors (who are non-Roma) who speak for their cause. There is a call for further investigation of Roma relations in Denmark to clarify their needs and how those needs can be approached successfully. Furthermore, there is a need to give the Roma a voice in the public debate and put Roma issues on the political agenda, not only in the media but also in the government body. To do so, Roma being recognized as an ethnic minority in Denmark equal to the German minority in Southern Jutland would be helpful. This would provide them with both legal rights and a voice. An acknowledgement such as this from Danish authorities would call for a nuanced presentation of the Roma in both public policy and in the press in general.

Author Contributions

C.L.O. was the primary researcher who collected and analyzed the data. L.E.K. was contributing by providing methodological guidance for the conduct of the research project and co-authored the present manuscript with C.L.O.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Fenger-Grøndahl, C.; Fenger-Grøndahl, M. Sigøjnere: 1000 år på Kanten af Europa; Aarhus Universitetsforlag: Århus, Denmark, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Parekh, N.; Rose, T. Health inequalities of the Roma in Europe: A literature review. Cent. Eur. J. Public Health 2011, 19, 139–142. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- European Commission. Roma Health Report Health Status of the Roma Population Data Collection in the Member States of the European Union; European Commission: Buxelles, Belgium, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Nordberg, C. Claiming citizenship: Marginalised voices on identity and belonging. Citizsh. Stud. 2006, 10, 523–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, J. Roma in the news: An examination of media and political discourse and what needs to change. People Place Policy 2014, 8, 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbetsmarknadsdepartementet. En Samordnad Och Långsiktig Strategi för Romsk Inkludering 2012–20222; Kulturdepartementet: Stockholm, Sweden, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. A EU Framework for National Roma Integration Strategies Up to 2020; European Commission: Buxelles, Belgium, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Europe 2020 Targets. European Commission, 2015. Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/europe2020/europe-2020-in-a-nutshell/targets/index_en.htm (accessed on 18 March 2018).

- Ullenhag, E. En Samordnad Och Långsiktig Strategi för Romsk Inkludering 2012–2032; Government Office: Stockholm, Sweden, 2011.

- Ministry for Social Affairs and Integration. Presentation to the European Commission of Denmark’s National Roma Strategy; Ministry for Social Affairs and Integration: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Discrimination in the EU 2012, Factsheet Denmark; European Commission: Bruxelles, Belgium, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Walgrave, S.; Van Aelst, P. Political Agenda Setting and the Mass Media. Oxf. Res. Encycl. Politics 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haavisto, C. Conditionally One of “Us”—A Study of Print Media, Minorities and Positioning Practices; University of Helsinki: Helsinki, Finland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Nordberg, C. Beyond Representation. Nordicom Rev. 2006, 27, 87–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ter Wal, J. Racism and Cultural Diversity in the Mass Media; European Monitoring Centre on Racism and Xenophobia (EUMC): Vienna, Austria, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Discrimination in the EU 2015, Factsheet Denmark; European Commission: Bruxelles, Belgium, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarts, R. Er europæerne ved at få nok af de åbne grænser? Information, 4 January 2014; 17. [Google Scholar]

- CSDH. Closing the gap in a generation: Health equity through action on the social determinants of health. In Final Report of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead, M.; Dahlgren, G. Concepts and Principles of Tackling Social Inequalities in Health. In Levelling Up Part 1; World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, L.; Winther Jørgensen, M. Discourse Analysis as Theory and Method; SAGE: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Fairclough, N. Discourse and Social Change; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Burr, V. An Introduction to Social Constructivism; SAGE: London, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault, M. The History of Sexuality. An Introduction; Vintage Books: New York, NY, USA, 1990; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault, M. The Archeology of Knowledge; Routledge: London, UK, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, S. Encoding/Decoding. In Culture, Media, Language: Working Papers in Cultural Studies, 1972–1979; Hall, S., Hobson, D., Lowe, A., Willis, P., Eds.; Hutchinson: London, UK, 1980; pp. 128–138. [Google Scholar]

- Fairclough, N. Critical Discourse Analysis. In The Critical Study of Language, 2nd ed.; Longman Applied Linguistic: Harlow, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, S. Representation: Cultural Representations and Signifying Practices; SAGE: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, S. Rassismus als ideologischer Diskurs. Das Argum. 1989, 178, 305–345. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dijk, T.A. Communicating Racism: Ethnic Prejudice in Thought and Talk; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dijk, T.A. The role of the media in the reproduction of racism. In Language, Power and Ideology: Studies in Political Discourse; Wodak, R., Ed.; John Benjamins Publishing Company: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1989; pp. 199–226. [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann, P.; Husband, C.; Clark, J. Race as News: A Study in the Handling of Race in the British National Press from 1963–1970; UNESCO: Paris, France, 1974; pp. 91–174. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, S. Folk Devils and Moral Panics; Paladin: St Alban’s, UK, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Rohloff, A.; Wright, S. Moral Panic and Social Theory Beyond the Heuristic. N. Z. Curr. Sociol. 2010, 58, 403–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahl Misund, B.; Clancy, A. Contradictory discourses of health promotion and disease prevention in the educational curriculum of Norwegian public health nursing: A critical discourse analysis. Scand. J. Public Health 2014, 42, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, S. Critical Policy Analysis: Exploring Contexts, Texts and Consequences. Discourse Stud. Cult. Politics Educ. 1997, 18, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reseke, L.; Toft, J. Læsertal: To Aviser Vokser. 2013. Available online: http://mediawatch.dk/secure/Medienyt/Aviser/article6212492.ece (accessed on 18 March 2018).

- Dahl, B.M. Critical discourse analysis perspective in Norwegian public health nursing curriculum in a time of transition. In Sociolinguistics—Interdisciplinary Perspectives; Jiang, X., Ed.; InTechOpen: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Crondahl, K. Towards Roma Empowerment and Social Inclusion through Work Integrated Learning; University of Southern Denmark: Esbjerg, Denmark, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Fairclough, N. Media Discourse; Edward Arnold: London, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Fairclough, N. Critical Discourse Analysis. In The Critical Study of Language; Pearson Education Limited: Harlow, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Social og Integrationsministeriet. Høringsnotat om Udkast til Danmarks nationale strategi til inklusion af romaer. In The Draft of Denmark’s National Strategy for Inclusion of Roma; Social of Integrationsministeriet: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. The European Union—Factsheet Denmark; European Commision: Buxelles, Belgium, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- McGarry, A.; Agarin, T. Unpacking the Roma participation puzzle: Presence, voice and influence. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2014, 40, 1972–1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGarry, A. Roma as a political identity: Exploring representations of Roma in Europe. Ethnicities 2014, 14, 756–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordberg, C. Integrating a Traditional Minority into a Nordic Society: Elite Discourse on the Finnish Roma. Soc. Work Soc. 2005, 3, 158–173. [Google Scholar]

- Eklund Karlsson, L.; Ringsberg, K.C.; Crondahl, K. Work-integrated learning and health literacy as catalysts for Roma empowerment and social inclusion: A participatory action research. Action Res. 2017, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frøslev, L. Romaer huserer over hele landet. Berlingske Tidende, 7 July 2010; 12. [Google Scholar]

- Westh, A.; Ellegaard, C. Sigøjnere kan ikke sendes hjem. Morgenavisen Jyllandsposten, 30 May 2010; 5. [Google Scholar]

- Bartels, C. Politiet må sadle om. Politiken, 11 April 2011; 5. [Google Scholar]

- Nordberg, C. Legitimising immigration control: Romani asylum—Seekers in the Finnish debate. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2004, 30, 717–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Søgaard, J.; Turan, F. Bygger hus for stjålne penge. Ekstra Bladet, 4 July 2012; 6. [Google Scholar]

- ABB. Politiken mener: Orden (Editorial). Politiken, 10 July 2010; 1. [Google Scholar]

- Thomsen, H. De uvelkomne. Morgenavisen Jyllands Posten, 20 April 2011; 20. [Google Scholar]

- Schultz, I. Fra Partipresse over Omnibuspresse til Segmentpresse. Journalistica: Tidskrift för Forskning i Journalistik 2007, 2, 5–26. [Google Scholar]

- Schrøder, K.; Kobbernagel, C. Danskernes Brug af Nyhedsmedierne; Roskilde Universitet: Roskilde, Denmark, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- KhosraviNik, M. The representation of refugees, asylum seekers and immigrants in British newspapers. A critical discourse analysis. J. Lang. Politics 2010, 9, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madsen, J.J. Læserne Vælger Avis Efter Egen Partifarve. 2011. Available online: http://journalisten.dk/laeserne-vaelger-avis-efter-egen-partifarve (accessed on 18 March 2018).

- Cohen, S. Folk Devils and Moral Panics; Routledge: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Facchini, G.; Mayda, A. From Individual Attitudes towards Migrants to Migration Policy Outcomes: Theory and Evidence; IZA Discussion Papers; No. 3512; Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA): Bonn, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kroon, A.; Kluknavská, A.; Vliegenthart, R.; Boomgaarden, H. Victims or perpetrators? Explaining media framing of Roma across Europe. Eur. J. Commun. 2016, 31, 375–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremlett, A. Making difference without creating a difference: Super-diversity as a new direction for research on Roma minorities. Ethnicities 2014, 14, 830–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vertovec, S. Super-diversity and its implications. Ethn. Racial Stud. 2007, 6, 1024–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupton, D. Discourse analysis: A new methology for understanding the ideologies of health and illness. Aust. J. Public Health 1992, 16, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).