How ‘Fake News’ Affects Autism Policy

Abstract

Government (any public official who influences or determines public policy, including school officials, city council members, county supervisors, etc.) does or does not do about a problem that comes before them for consideration and possible action.

There is a fog that has been generated by corporate interests and organizations attempting to sell their services and products to desperate or poorly educated consumers.(p. 1)

The rise of fake news highlights the erosion of long-standing institutional bulwarks against misinformation in the internet age. Concern over the problem is global. … A new system of safeguards is needed.([22], p. 1094)

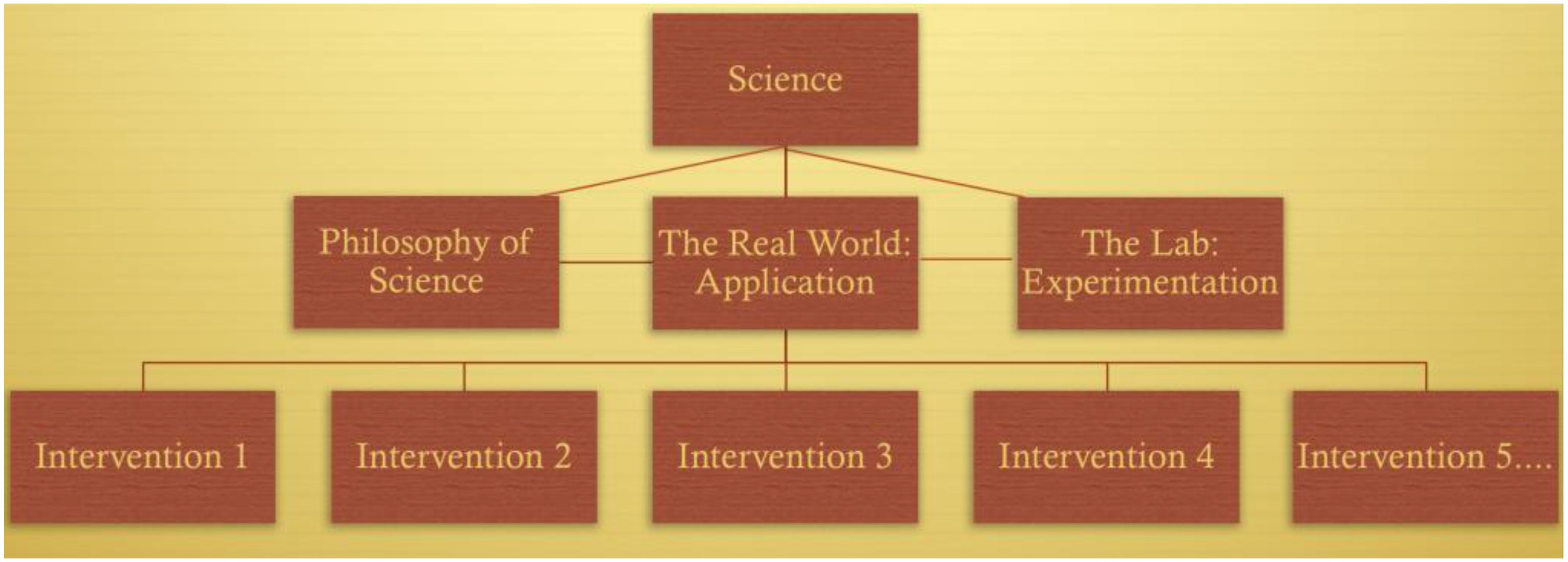

In the ideal image of science, scientists work in a world detached from our daily political squabbles, seeking enduring empirical knowledge. Scientists are interested in timeless truths about the natural world rather than current affairs. Policy, on the other hand, is that messy realm of conflicting interests, where our temporal (and often temporary) laws are implemented, and where we craft the necessary compromises between political ideals and practical limits. This is no place for discovering truth.

Without reliable knowledge about the natural world, however, we would be unable to achieve the agreed upon goals of a public policy decision. … Science is essential to policymaking if we want our policies concerning the natural world to work.([25], p. 3)

- (i)

- Practice within the boundaries of their competence [and]

- (ii)

- Engage in Continued Professional Development.

As a general rule, in matters concerning physics, the Institute of Physics in Ireland would seek to have appropriately qualified physicists represented on any review panel which might be reporting on ‘findings from physics’.(Institute of Physics in Ireland, personal communication)

Science and Autism Policies in North America

Over 30 years of research demonstrate the efficacy of applied behavioral methods in reducing inappropriate behavior and in increasing communication, learning, and appropriate social behavior.

There is sufficient evidence to categorize ABA as medical therapy rather than purely educational.

The absence of ABA means that children with autism are excluded from the opportunity to access learning, with the consequential deprivation of skills, the likelihood of isolation from society and the loss of the ability to exercise the rights and freedoms to which Canadians are entitled.

To support their use of applied behaviour analysis (ABA) as an effective instructional approach in the education of many students with autism spectrum disorders (ASD). This memorandum establishes a policy framework to support incorporation of ABA methods into school boards’ practices. The use of ABA instructional approaches may also be effective for students with other special education needs.

Science and Autism Policies Elsewhere

A good example is the Linea Guida 21, a guideline on effective treatments for autism recently published by the Italian Istituto Superiore di Sanità (ISS), a research branch of the Italian Ministry of Health. This guideline asserts that behavioural interventions are most effective in autism treatment. However, because no behaviour analyst, academic or professional trained in ABA, was on the scientific board that evaluated the research, the guideline report contained worrying examples of confusion between the science, procedures, models and protocols for intervention.([48], p. 169)

Unfortunately, most misconceptions about behaviorism, … will be difficult to correct because they owe more to “academic folklore” than to scholarly analysis. This academic folklore is passed from textbook to textbook and from teacher to student as unquestioned fact. The misconceptions are so well accepted that genuine critical investigation is brought to a halt.([51], p. 117)

- Preparing uncritical, incomplete research reviews related to a practice or policy;

- Ignoring counter evidence to favoured views and hiding limitations of research;

- Ignoring or misrepresenting well-argued alternative views and related evidence;

- Arguing ad hominem (attacking the critic) rather than ad rem (responding to the argument). (p. 8)

Local professionals who work with young children suggested to Task Group members that they would have grave reservations about being involved in subjecting such young children to such an intense behavioural programme for fear of causing some kind of psychological damage.([55], p. 38)

… the reader may be interested to know that aversives were a generally accepted practice during the 1960s and 1970s. TEACCH, for example also advocated the use of aversives at that time. In their training manual, Schopler et al. [69] describe the use of ‘aversive and painful procedures’ such as meal deprivation, ‘slaps or spanks on the bottom’, or ‘electric shock, unpleasant tasting or smelling substances’ as appropriate interventions if positive methods are ineffective.([68], p. 31)

- Producing evidence-based guidance and advice for health, public health and social care practitioners.

- Developing quality standards and performance metrics for those providing and commissioning health, public health and social care services.

- Providing a range of information services for commissioners, practitioners and managers across the spectrum of health and social care [70].

During guideline development, there was evidence from randomised controlled trials (RCT) and systematic reviews about psychosocial interventions to improve the core features of autism. However, none of this evidence was about ABA.([73], pp. 1, 7, 8, 10, 21, & 23)

Science has evolved over many centuries to become an integral part of modern society, underpinning our health, wealth, and cultural fabric. Yet scientific evidence is often willfully disregarded by politicians worldwide.

They often cherry pick or ignore the science when it does not accord with their political agenda. We have seen ‘alternative facts’ supplant scientific and other evidence bases in this ‘post-fact’ era.

Applied Behaviour Ana (ABA) is one of many commercially available interventions for children with autism.[89]

I continue to accept this view and, therefore, do not promote one type of intervention over another.[90]

in terms of her professional convictions, insofar as she has a principle or a broadly-based objection to ABA, in that she has never recommended it for anyone, and also in terms of the fact that she has been retained by the Department in very many cases, and the same issue has arisen, and her attitude has been the same on every occasion.([91], p. 10)

What is a scientific study without random assignment to groups?([52], p. 444)

Each child with an illness has his/her own individual needs and it would be inappropriate to invest in only one thing like medical science.

In carrying out its research advisory role the Research Advisory Committee will not seek to espouse or promote a particular methodology in the care and/or treatment of people with autism.(sic)

To answer your queries the Department of Education is involved in education policies for children between 3–19 therefore it would not be for us to determine whether ABA is recognised as a science.(personal communication)

Because there are many different interventions, programmes and techniques used to help individuals with autism which incorporate the principles of applied behaviour analysis it is not possible to provide a ranking for applied behavioural (sic) analysis as a whole.

Although there are several journals devoted to the science of behaviour analysis, the two primary journals are the Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior and the Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. Both are highly rigorous journals with strong citation indices. But all of this is well established fact and what surprises me is that any educated person would question it.(Personal communication)

Interventions in autism must, of necessity, vary according to the specific needs of the individual on the autism spectrum. However, multidisciplinary teams working with individuals with ASDs should include at least one psychologist who possesses specific competencies and skills, in addition to other relevant personnel, such as occupational therapists, mental health workers etc.

The BPS received a large number of messages about the report. Many parents and professionals enthusiastically welcomed it (e.g., ABAA4ALL [104]). However, there were also some critics and the BPS decided to yield to them and immediately withdrew the guidelines from their webpages, without consultation or notification of the review panel or the public.In the UK, psychological treatment for ASD has traditionally been offered by a psychologist, however, behaviour analysis-based intervention should be supervised and/or delivered by Board Certified Behavior Analysts (BCBA). Most BCBAs have a background in psychology and it is noted that a growing number are part of/lead multidisciplinary autism teams. Note that this document does not recommend that BCBAs should supplant psychologists, but recognises their contribution to the supervision and/or delivery of interventions, depending upon the specific needs of the individual client.

3. Conclusions

Members of the scientific community share a frustration: many attempts to communicate science are badly received. This frustration is particularly evident in politicized environments.(p. 14048)

All that is genuinely controversial about behaviorism stems from its primary idea, that a science of behavior is possible. At some point in its history, every science has had to exorcise imagined causes (hidden agents) that supposedly lie behind or under the surface of natural events.(p. 1)

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dillenburger, K.; Jordan, J.-A.; McKerr, L.; Lloyd, K.; Schubotz, D. Autism awareness in children and young people: Surveys of two populations. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2017, 61, 766–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dillenburger, K.; Jordan, J.-A.; McKerr, L.; Keenan, M. The Millennium child with autism: Early childhood trajectories for health, education and economic wellbeing. Dev. Neurorehabil. 2015, 18, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buescher, A.V.S.; Cidav, Z.; Knapp, M.; Mandell, D.S. Costs of Autism Spectrum Disorders in the United Kingdom and the United States. JAMA Pediatr. 2014, 168, 721–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silberman, S. Neurotribes: The Legacy of Autism and How to Think Smarter about People Who Think Differently; Allen & Unwin: Crows Nest, Australia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Howlin, P.; Savage, S.; Moss, P.; Tempier, A.; Rutter, M. Cognitive and language skills in adults with autism: A 40-year follow-up. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2014, 55, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howlin, P.; Goode, S.; Hutton, J.; Rutter, M. Adult outcome for children with autism. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2004, 45, 212–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fein, D.; Barton, M.; Eigsti, I.-M.; Kelley, E.; Naigles, L.; Schultz, R.T.; Stevens, M.; Helt, M.; Orinstein, A.; et al. Optimal outcome in individuals with a history of autism. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2013, 54, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orinstein, A.J.; Helt, M.; Troyb, E.; Tyson, K.E.; Barton, M.L.; Eigsti, I.-M.; Naigles, L.; Fein, D.A. Intervention for optimal outcome in children and adolescents with a history of autism. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 2014, 35, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Center for Civic Education. Public Policy. Available online: http://www.civiced.org/pc-program/instructional-component/public-policy (accessed on 24 March 2018).

- Business Dictionary. Public Policy. Business Dictionary. 2018. Available online: www.businessdictionary.com/definition/public-policy.html (accessed on 24 March 2018).

- Lopatto, E. Yes, Science Is Political. The Verge. 2017. Available online: https://www.theverge.com/2017/1/19/14258474/trump-inauguration-science-politics-climate-change-vaccines (accessed on 2 April 2018).

- Lupia, A. Communicating science in politicized environments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110 (Suppl. 3), 14048–14054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCright, A.M.; Dentzman, K.; Charters, M.; Dietz, T. The influence of political ideology on trust in science. Environ. Res. Lett. 2013, 8, 44029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pielke, R.J. When Scientists Politicize Science. Regulation: Environment. 2006. Available online: https://www.colorado.edu/geography/class_homepages/geog_5161_ttv_s09/pielke_06.pdf (accessed on 2 April 2018).

- Smith, A. Making an Impact: When Science and Politics Collide. The Guaridan. 1 January 2012. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/science/2012/jun/01/making-impact-scientists (accessed on 2 April 2018).

- Gambrill, E. Evidence-informed practice: Antidote to propaganda in the helping professions? Res. Soc. Work Pract. 2010, 20, 302–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambrill, E.D. Propaganda in the Helping Professions; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Balmas, M. When fake news becomes real: Combined exposure to multiple news sources and political attitudes of inefficacy, alienation, and cynicism. Commun. Res. 2014, 41, 430–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EJN, ‘Fake News’: Disinformation, Misinformation and Mal-Information. Ethical Journalism Network. 2018. Available online: https://ethicaljournalismnetwork.org/tag/fake-news (accessed on 20 April 2018).

- Boyd, D. The Science of Fake News Gets a Boost. Human World: EarthSky. 2018. Available online: http://earthsky.org/human-world/fake-news March 2018-article-science-calling-for-studies (accessed on 20 April 2018).

- Mehra, P. Fake News Needs a Definition. Business Line. 2018. Available online: https://www.thehindubusinessline.com/opinion/columns/from-the-viewsroom/fake-news-needs-a-definition/article23584881.ece (accessed on 20 April 2018).

- Lazer, D.M.J.; Baum, M.A.; Benkler, Y.; Berinsky, A.J.; Greenhill, K.M.; Menczer, F.; Metzger, M.J.; Nyhan, B.; Pennycook, G.; Rothschild, D.; et al. The science of fake news: Addressing fake news requires a multidisciplinary effort. Science 2018, 59, 1094–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heward, W.L. Ten faulty notions about teaching and learning that hinder the effectiveness of special education. J. Spec. Educ. 2003, 36, 186–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainscow, M.; Chapman, C. Using Research to Change Educational Systems: Possibilities and Barriers (BERA Blog). British Educational Research Association (BERA) Blog (Nov. 6). 2017. Available online: https://www.bera.ac.uk/blog/using-research-to-change-educational-systems-possibilities-and-barriers (accessed on 11 December 2017).

- Douglas, H.E. Science, Policy, and the Value-Free Ideal. 2009. Available online: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=LcFvKeOJRmgC&pg=PA3&lpg=PA3&dq=Without+reliable+knowledge+about+the+natural+world,+however,+we+would+be+unable+to+achieve+the+agreed+upon+goals+of+a+public+policy+decision&source=bl&ots=-2F27DZXs2&sig=LjnHUNmbXcw_hfuHKE (accessed on 21 April 2018).

- BPS, Code of Ethics and Conduct; British Psychological Society. British Psychological Society. 2009. Available online: https://beta.bps.org.uk/sites/beta.bps.org.uk/files/Policy-Files/Code of Ethics and Conduct %282009%29.pdf (accessed on 3 August 2017).

- Eikeseth, S.; Smith, T.; Jahr, E.; Eldevik, S. Outcome for children with autism who began intensive behavioral treatment between ages 4 and 7: A comparison controlled study. Behav. Modif. 2007, 31, 264–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howard, J.S.; Stanislaw, H.; Green, G.; Sparkman, C.R.; Cohen, H.G. Comparison of behavior analytic and eclectic early interventions for young children with autism after three years. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2014, 35, 3326–3344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howard, J.S.; Sparkman, C.R.; Cohen, H.G.; Green, G.; Stanislaw, H. A comparison of intensive behavior analytic and eclectic treatments for young children with autism. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2005, 26, 359–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- California Department of Education and Devleopmental Servcies, Best Practices for Designing and Delivering Effective Programs for Individuals with Autistic Spectrum Disorders. 1997. Available online: http://www.feat-fmc.org/assets/cabestprac.pdf (accessed on 25 April 2018).

- Maurice, C. Let Me Hear Your Voice: A Family’s Triumph over Autism; Robert Hale: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Surgeon General, Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. 1999. Available online: http://profiles.nlm.nih.gov/ps/retrieve/ResourceMetadata/NNBBHS (accessed on 21 July 2014).

- AutismSpeaks, Federal Agency Renders Landmark Decision on ABA Coverage. 2012. Available online: https://www.autismspeaks.org/advocacy/advocacy-news/federal-agency-renders-landmark Decision-aba-coverage (accessed on 24 March 2018).

- AAP, Caring for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders. American Academy of Pediatrics. 2007. Available online: https://www.aap.org/en-us/advocacy-and-policy/aap-health-initiatives/pages/Caring-for-Children-with-Autism-Spectrum-Disorders-A-Resource-Toolkit-for-Clinicians.aspx (accessed on 24 March 2018).

- New York State Department of Health, Clinical Practice Guidelines: Quick Reference Guide for Parents and Professionals. Autism/Pervasive Development Disorders. Assessment and Intervention for Young Children (Age 0–3 Years); 2011. Available online: http://www.health.ny.gov/publications/4216.pdf (accessed on 24 March 2018).

- Autism Society Canada, Canadian Autism Research Agenda and Canadian Autism Strategy. White Paper. 2004. Available online: http://www.autismsocietycanada.ca/images/dox/ASC_Internal/finalwhite-eng.pdf (accessed on 27 June 2015).

- Kiteley, F.J. McGuinty Government to Appeal Autism Ruling. 2005. Available online: dawn.thot.net/autism-ruling.html (accessed on 7 September 2014).

- Autism Canada, ABA. Autism Canada. 2018. Available online: https://autismcanada.org/living-with-autism/treatments/non-medical/behavioural/aba/ (accessed on 24 March 2018).

- PPM-140, Incorporating Methods of Applied Behaviour Analysis (ABA) into Programs for Students with Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD). 2007. Available online: http://www.edu.gov.on.ca/extra/eng/ppm/140.pdf (accessed on 23 March 2018).

- Autism Speaks, State Initiatives. Autism Speaks. 2018. Available online: http://www.autismspeaks.org/advocacy/states (accessed on 21 April 2018).

- Kennedy Krieger Institute, Kennedy Krieger Institute at Johns Hopkins Children’s Center. 2018. Available online: https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/johns-hopkins-childrens-center/patients-and-families/locations-parking/kennedy-krieger-institute.html (accessed on 21 April 2018).

- Unumb, L. Keynote Address by Dr Lorri Unumb at Centre for Behaviour Analysis (QUB) Conference. Queen’s University Belfast. 2013. Available online: http://www.mediator.qub.ac.uk/ms/Quart/DrLorriUnumb.m4v (accessed on 25 November 2017).

- BACB, Behavior Analyst Certification Board. BACB. 2018. Available online: www.bacb.com (accessed on 3 April 2018).

- APBA, Association of Professional Behavior Analysts. 2018. Available online: http://www.apbahome.net/ (accessed on 21 April 2018).

- Keenan, M.; Dillenburger, K. When all you have is a hammer …: RCTs and hegemony in science. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2011, 5, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keenan, M. A normalising agenda for the nail that sticks out. Špeciálny Pedagóg Slovakian J. Spec. Educ. 2016, 5, 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- BACB, Applied Behavior Analysis Treatment of Autism Spectrum Disorder: Practice Guidelines for Healthcare Funders and Managers. Behavior Analyst Certification Board. 2014. Available online: http://bacb.com/Downloadfiles/ABA_Guidelines_for_ASD.pdf (accessed on 14 January 2015).

- Keenan, M.; Dillenburger, K.; Röttgers, H.-R.; Dounavi, K.; Jónsdóttir, S.L.; Moderato, P.; Schenk, J.J.A.M.; Virués-Ortega, J.; Roll-Pettersson, L. Autism and ABA: The gulf between North America and Europe. Rev. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2014, 2, 167–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillenburger, K. The Emperor’s new clothes: Eclecticism in autism treatment. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2011, 5, 1119–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- STAMPPP, Science and the Treatment of Autism: A Multimedia Package for Parents and Professionals. 2013. Available online: http://www.stamppp.com/ (accessed on 6 February 2015).

- Todd, J.T. The great power of steady misrepresentation: Behaviorism’s presumed denial of instinct. Behav. Anal. 1987, 10, 117–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, M.-L. Letter to the Editor: ABA—Giving Science a Bad Name? The Psychologist. 2008. Available online: http://www.thepsychologist.org.uk/archive/archive_home.cfm?volumeID=21&editionID=160&ArticleID=1350 (accessed on 29 August 2014).

- Jordan, R. Parents’ Education as Autism Therapists: Applied Behaviour Analysis in Context; Keenan, M., Kerr, K., Dillenburger, K., Eds.; Jessica Kingsley Publishers: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Fennell, B.; Dillenburger, K. Applied behaviour analysis: What do teachers of students with autism spectrum disorder know. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2018, 87, 110–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DENI, Report of the Task Group on Autism. In Department of Education Northern Ireland; 2002. Available online: http://www.deni.gov.uk/index/7-special_educational_needs_pg/special_educational_needs_-_reports_and_publications-newpage-2/special_educational_needs_-_reports_and_publications-newpage-4.htm (accessed on 20 December 2014).

- Dillenburger, K.; McKerr, L.; Jordan, J.-A. Lost in translation: Public policies, evidence-based practice, and Autism Spectrum Disorder. Int. J. Disabil. Dev. Educ. 2014, 61, 134–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keenan, M. Science that could improve the lives of people with autism is being ignored. The Conversation. 2015. Available online: https://theconversation.com/science-that-could-improve-the-lives-of-people-with-autism-is-being-ignored-39951 (accessed on 12 May 2015).

- O’Dowd, J. Department of Education-Written Answers to Questions Monday 16 March 2015–Friday 20 March 2015; AQW 43523/11-15; Hansard: Belfast, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Gillen, E.; Keenan, M. When Policy Decisions for Autism Treatment in Europe are Hijacked by a Category Mistake. Psychology 2017, 56, 72–78. [Google Scholar]

- Mattaini, M. Leading Experts Concerned about Maginnis Review of Autism Services. Parents Education as Autism Therapists. 2008. Available online: www.peatni.org (accessed on 22 July 2014).

- Howlin, P. 70 Years of autism research: How far have we come? Autism Eur. Newsl. 2013, 60, 4–6. [Google Scholar]

- PEAT, Northern Ireland Task Group Report on Autism: PEAT Response. Parents Education as Autism Therapists. 2002. Available online: http://www.imagesforbehaviouranalysts.com/uploads/1/0/2/5/10258235/peatresponse.pdf (accessed on 2 December 2017).

- Keenan, M.; Kerr, K.P.; Dillenburger, K. Parents Education as Autism Therapists; Jessica Kingsley Publishers: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, J. In the matter of the Children (Northern Ireland) Order 1995. In High Court of Justice in Norhtern Ireland-Family Division; 2008. Available online: http://www.courtsni.gov.uk/en-GB/JudicialDecisions/PublishedByYear/Documents/2008/2008NIFam2/j_j_MOR7045Final.htm (accessed on 2 December 2017).

- Schopler, E.; Mesibov, G.B.; Hearsey, K. Structured teaching in the TEACCH System. In Learning and Cognition in Autism; Schopler, E., Mesibov, G.B., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1995; pp. 243–268. [Google Scholar]

- Warren, Z.; Weele, J.V.; Stone, W.; Bruzek, J.L.; Nahmias, A.S.; Foss-Feig, J.H.; McPheeters, M.L. Therapies for children with autism spectrum disorders. Agency Healthc. Res. Qual. 2011, 1, 878–880. [Google Scholar]

- Dillenburger, K.; Keenan, M. The psychology of smacking children: The dangers of misguided and outdated applications of psychological principles. Irish Psychol. 1994, 20, 56–58. [Google Scholar]

- Sallows, G. Educational interventions for children with autism in the UK. Early Child Dev. Care 2000, 163, 25–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schopler, E.; Reichler, R.J.; Lansing, M. Individualized Assessment and Treatment for Autistic and Developmentally Disabled Children. 2: Teaching Strategies for Parents and Professionals; Pro-Ed.: Austin, TX, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- NICE, What We Do. 2017. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/about/what-we-do (accessed on 14 July 2017).

- NICE, Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT). National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. 2017. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/about/what-we-do/our-programmes/nice-advice/iapt#IAPT-conditions (accessed on 15 December 2017).

- NICE, Autism Spectrum Disorder in under 19s: Support and Management (CG170). National Institute of Clinical Excellence. 2013. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg170 (accessed on 30 January 2018).

- NICE, Appendix B: Stakeholder Consultation Comments Table. 2016. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg138/evidence/appendix-b-stakeholder-consultation-comments-table-2603603055 (accessed on 4 August 2017).

- NICE, Autism: Recognition, Referral, Diagnosis and Management of Adults on the Autism Spectrum: Guidance and Guidelines. National Institute of Clinical Excellence. 2012. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/CG142/resources (accessed on 14 January 2015).

- NICE, Autism in Children and Young People GDG Membership List. NICE. 2012. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg170/documents/autism-management-of-autism-in-children-and-young-people-gdg-membership-list2 (accessed on 24 November 2017).

- National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) and NICE, Response to Consultation for Autism: The Management and Support of Children and Young People on the Autism Spectrum. National Institute for Clinical Excellence. 2013. Available online: http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/CG170/chapter/introduction (accessed on 21 August 2014).

- National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE). Personal Email Correspondence: Subject Heading: NICE enq ref EH82062 RE: NICE Guidelines 170; NICE: London, UK, 2017; p. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, E.K. A case study in the misrepresentation of applied behavior analysis in autism: The Gernsbacher lectures. Behav. Anal. 2009, 32, 205–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motiwala, S.S.; Gupta, S.; Lilly, M.B.; Ungar, W.J.; Coyte, P.C. The cost-effectiveness of expanding intensive behavioural intervention to all autistic children in Ontario: In the past year, several court cases have been brought against provincial governments to increase funding for Intensive Behavioural Intervention. Healthc. Policy 2006, 1, 135–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters-Scheffer, N.; Didden, R.; Korzilius, H.; Matson, J. Cost comparison of early intensive behavioral intervention and treatment as usual for children with autism spectrum disorder in The Netherlands. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2012, 33, 1763–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chasson, G.S.; Harris, G.E.; Neely, W.J. Cost Comparison of Early Intensive Behavioral Intervention and Special Education for Children with Autism. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2007, 16, 401–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccininni, C.; Bisnaire, L.; Penner, M. Cost-effectiveness of wait time reduction for Intensive Behavioral Intervention services in Ontario, Canada. JAMA Pediatr. 2016, 171, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ÓCuanacháin, C. Couple face costs in autism case. Irish Health.com. 2008. Available online: http://www.irishhealth.com/article.html?id=12978 (accessed on 18 January 2015).

- Autism Act (Northern Ireland), Autism Act (Northern Ireland) 2011. In Legislation.gov.uk; 2011. Available online: http://www.legislation.gov.uk/nia/2011/27/contents/enacted (accessed on 11 December 2014).

- Northern Ireland Executive, Autism Strategy (2013 2010) and Action Plan (2013 2016). In DHSSPS; 2014. Available online: www.dhsspsni.gov.uk/autism-strategy-action-plan 2013.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2014).

- BASE Project, BASE Reports (Full Copies; Free Download). Centre for Behaviour Analysis, Queen’s University Belfast, 2016. Available online: http://www.qub.ac.uk/research-centres/CentreforBehaviourAnalysis/Research/BenchmarkingAutismServiceEfficacyBASE/ (accessed on 2 April 2016).

- Baldwin, K. When Politicians Listen to Scientists, We All Benefit. The Conversation. 2017. Available online: https://theconversation.com/when-politicians-listen-to-scientists-we-all-benefit-74443 (accessed on 21 April 2018).

- Jendoubi, C. Email to Hugh McKenna dated 21 November 2012 15:37. Obtained under the Freedom of Information Act. Free Inf. Req. 2012. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LFVykFNOGdw (accessed on 8 May 2018).

- Ruane, C. Answer to Ministerial question from George Robinson. Personal communication, Department of Education, 2009.

- O’Dowd, J. Committee For Education: Minutes of Proceedings; Department of Health: Belfast, UK, 2014. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Y_IXmT57mU8 (accessed on 8 May 2018).

- The High Court Dublin; Sean O’ Cuanachain (A minor suing by his father and next friend Cian O’Cuanachain); The Minister for Education and Science; The Minister for Health and Children; The Health Service Executive, Ireland; The Attorney General. Action Heard before Mr. Justice Peart Thursday, 15th June 2006 Day 52. 2006. Available online: http://www.courts.ie/judgments.nsf/6681dee4565ecf2c80256e7e0052005b/bebecd99d1c33b9780257356004dbb78?OpenDocument&Highlight=0,education (accessed on 8 May 2018).

- Nardini, C. The Ethics of Clinical Trials. eCancerMedicalScience. 2014. Available online: https://ecancer.org/journal/8/full/387-review-the-ethics-of-clinical-trials.php (accessed on 7 May 2018).

- Smith, G.C.S.; Pell, J.P. Parachute use to prevent death and major trauma related to gravitational challenge: systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Br. Med. J. (Clin. Res. Ed.) 2003, 327, 1459–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gast, D.L.; Ledford, J.R. Single Case Research Methodology: Applications in Special Education and Behavioral Sciences. 2014. Available online: https://www.amazon.co.uk/Single-Case-Research-Methodology-Applications/dp/0415827914 (accessed on 21 April 2018).

- Research Autism, Single-Case Designs Technical Documentation. Research Autism Publications. 2010. Available online: http://researchautism.net/publications/6514/single-case-designs-technical-documentation (accessed on 16 July 2017).

- WWC, Single-Case Design Technical Documentation: What Works Clearinghouse. In What Works Clearinghouse; 2010. Available online: http://ies.ed.gov/ncee/wwc/documentsum.aspx?sid=229 (accessed on 9 September 2015).

- Chiesa, M. Radical Behaviorism: The Philosophy and the Science. Cambridge Center for Behavioral. 1984. Available online: http://www.amazon.com/Radical-Behaviorism-The-Philosophy-Science/dp/0962331147 (accessed on 5 December 2015).

- Research Autism, Applied Behaviour Analysis. 2017. Available online: http://www.researchautism.net/autism-interventions/types/behavioural-and-developmental/behavioural/applied-behaviour-analysis-and-autism (accessed on 27 April 2018).

- EABA, European Association for Behaviour Analysis. European BACB Validated Courses Sequences. 2018. Available online: http://www.europeanaba.org/courses/ (accessed on 20 April 2018).

- Ulster University, Honour for Autism Campaigner. Ulster University Website. 2012. Available online: https://www.ulster.ac.uk/news/2012/july/honour-for-autism-campaigner (accessed on 21 April 2018).

- Parent Petition, Provide the Choice of ABA-Based Interventions for Children with ASD in Northern Ireland. Change.org. 2013. Available online: https://www.change.org/p/jim-wells-health-minister-john-o-dowd-education-minister-provide-the-choice-of-aba-based-intervention-for-children-with-asd-in-northern-ireland (accessed on 27 April 2018).

- British Psychological Society (BPS), Autistic Spectrum Disorders: Guidance for psychologists. British Psychological Society. 2016. Available online: http://www.bps.org.uk/system/files/Public files/Autism and CJS/Autistic Spectrum Disorders WEB(1).pdf (accessed on 1 September 2016).

- NIHR, Patients and the Public. 2017. Available online: https://www.nihr.ac.uk/patients-and-public/ (accessed on 17 December 2017).

- ABA4ALL, Community of Parents of Children with Autism. 2014. Available online: www.facebook.com/ABAforallchildren/info (accessed on 8 August 2014).

- Keenan, M. Autism in Northern Ireland—The Tragedy and the Shame. The Psychologist. 2004. Available online: https://thepsychologist.bps.org.uk/volume-17/edition-2/autism-northern-ireland-tragedy-and-shame (accessed on 24 March 2018).

- The Skeptical Advisor, Simon Baron-Cohen’s Fantastically False Article on Radical Behavior: An Example of Valid, but False Premises. The Skeptical Advisor. 2014. Available online: http://theskepticaladvisor.wordpress.com/2014/01/21/simon-baron-cohens-fantastically-false-article-on-radical-behavior-an-example-of-valid-but-false-premises/ (accessed on 11 November 2014).

- Baron-Cohen, S. What Scientific Idea Is Ready for Retirement? Radical Behaviourism. Edge. 2014. Available online: https://www.edge.org/response-detail/25473 (accessed on 2 April 2018).

- Cradden, J. The battle over ABA: Autism education in limbo. The Irish Times. 2014. Available online: https://www.irishtimes.com/news/education/the-battle-over-aba-autism-education-in-limbo-1.1798534 (accessed on 8 May 2018).

- Kelly, M.; Martin, N.; Dillenburger, K.; Kelly, A.; Miller, M.M. Spreading the news: History, successes, challenges and the ethics of effective dissemination. Behav. Anal. Pract. 2018, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todd, J.T.; Morris, E.K. Misconception and miseducation: Presentations of Radical Behaviorism in psychology textbooks. Behav. Anal. 1983, 6, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, R.; Burgess, H. Mythmaking: How introductory psychology texts present B.F. Skinner’s analysis of cognition. Psychol. Rec. 1997, 47, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlinger, H.D. Not so fast, Mr. Pinker: A behaviorist looks at the blank slate. A review of Steven Pinker’s The blank slate: The modern denial of human nature. Behav. Soc. Issues 2012, 12, 75–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, W. Understanding Behaviorism: Behavior, Culture, and Evolution; Blackwell Publishing Ltd.: Malden, MA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- MyKidUp, My Kid Up. 2011. Available online: http://www.mykidup.com/pt/ (accessed on 22 April 2018).

- Dillenburger, K.; Röttgers, H.-R.; Dounavi, K.; Sparkman, C.; Keenan, M.; Thyer, B.; Nikopoulos, C. Multidisciplinary Teamwork in Autism: Can One Size Fit All? Aust. Educ. Dev. Psychol. 2014, 31, 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandalovičová, J. Jana Discussing ABA Based Intervention in Czech Republic-YouTube. 2018. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Nl8pvAQks6g&t=7s (accessed on 22 April 2018).

- Gandalovičová, J. The arrival of ABA in the Czech Republic. Eur. Assoc. Behav. Anal. Newsl. 2016, 12, 7–9. [Google Scholar]

- PEAT, Parents Education as Autism Therapists (Northern Ireland). 1997. Available online: http://peatni.org/ (accessed on 20 April 2018).

- NI4Kids, PEAT Named NI4Kids Family Awards 2016 Finalist. 2016. Available online: http://www.peatni.org/news/view/27/peat-named-ni4kids-family-awards 2016-finalist (accessed on 21 April 2018).

- SimpleSteps, Simple Steps Autism: The Online Teaching Platform for the Treatment of Autism. Parents Education as Autism Therapists. 2013. Available online: www.simplestepsautism.com (accessed on 29 October 2014).

- Peregrine, P.N. Seeking Truth among ‘Alternative Facts’. The Conversation. 2017. Available online: https://theconversation.com/seeking-truth-among-alternative-facts-72733 (accessed on 4 December 2017).

- Foxx, R.M.; Mulick, J.A. Controversial Therapies for Autism and Intellectual Disabilities: Fad, Fashion, and Science in Professional Practice, 2nd ed.; Routledge: Oxford, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, H.; Byrne, T. Mikey—Dealing with courts, tribunals and politicians. In Applied Behaviour Analysis and Autism: Building a Future Together; Keenan, M., Henderson, M., Dillenburger, K., Kerr, K.P., Eds.; Jessica Kingsley Publishers: London, UK; Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2005; pp. 208–218. [Google Scholar]

- The Irish Times, The Sinnott Case. 2000. Available online: https://www.irishtimes.com/opinion/the-sinnott-case-1.1106719 (accessed on 4 December 2017).

- The Irish Times, Autistic Boy Awarded Costs after Failed Court Bid. The Irish Times. 2005. Available online: https://www.irishtimes.com/news/autistic-boy-awarded-costs-after-failed-court-bid-1.1178956 (accessed on 4 December 2017).

- WalesOnline, Autistic Child’s Parents Lose Treatment Case. WalesOnline. 2005. Available online: http://www.walesonline.co.uk/news/wales-news/autistic-childs-parents-lose-treatment-2393042 (accessed on 4 December 2017).

- UNCRPD, United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. United Nations. 2006. Available online: http://www.un.org/disabilities/convention/conventionfull.shtml (accessed on 13 October 2014).

- UNCRC, United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. UN Office of the High Commissioner. 1990. Available online: http://www.ohchr.org/EN/ProfessionalInterest/Pages/CRC.aspx (accessed on 22 April 2018).

| 1 | Implementing an ABA program is not something that is ‘done to someone’, rather it is something that is ‘done with someone’. The goal is to provide opportunities for an individual to acquire skills that increases opportunities to make choices in life. Keenan [46] commented on the misinformation that is circulated about this goal: ‘It is considered a perversion by some to encourage parents to employ the principles of behaviour in the context of educating their children with autism. Using insights from behaviour analysis, it is argued, is something to be discouraged. ABA is caricatured as NOT being person-centred and it is also argued that designing experiences based on awareness of the influence of [laws of learning] to educate someone necessarily involves coercion, and that the science is guilty of forcing people to conform to one view of the world.’ (p. 7) |

| Discipline | RCTs and Systematic Reviews |

|---|---|

| Medical Science | None available |

| Dentistry | None available |

| Pediatrics | None available |

| Audiology | None available |

| Nursing | None available |

| Pharmacy | None available |

| Radiology | None available |

| Speech-Language Pathology | None available |

| Occupational therapy | None available |

| Psychology; clinical; educational | None available |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Keenan, M.; Dillenburger, K. How ‘Fake News’ Affects Autism Policy. Societies 2018, 8, 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc8020029

Keenan M, Dillenburger K. How ‘Fake News’ Affects Autism Policy. Societies. 2018; 8(2):29. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc8020029

Chicago/Turabian StyleKeenan, Mickey, and Karola Dillenburger. 2018. "How ‘Fake News’ Affects Autism Policy" Societies 8, no. 2: 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc8020029

APA StyleKeenan, M., & Dillenburger, K. (2018). How ‘Fake News’ Affects Autism Policy. Societies, 8(2), 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc8020029