Abstract

The role of media in collective action repertoires has been extensively studied, but media as an agent of socialization in social movement identity is less understood. It could be that social movement media is normalizing a particular activist identity to the exclusion of other demographics. For instance, Harper has identified white-centrism in anti-speciesist media produced by the Nonhuman Animal rights movement and supposes that this lack of diversity stunts movement potential. Using the lesser-studied Nonhuman Animal rights movement as a starting point, this study investigates two prominent Nonhuman Animal rights magazines. We compare those findings with an analysis of comparable leftist movements also known to exhibit diversity strains. A content analysis of Nonhuman Animal rights, women’s rights, and gay rights magazine covers spanning from 2000 to 2012 was undertaken to determine the manifestation of gender, race, body type, and sexualization. We find that the Nonhuman Animal rights media in our sample overwhelmingly portrays white women with a tendency toward thinness, but with low levels of sexualization as comparable to that of the other movements. All three movement samples unevenly depicted gender, overrepresented whites, and underrepresented non-thin body types.

1. Introduction

For social movements, media presence matters [1,2]. Exactly who is presented and how they are presented also matters. Diversity is an important strategy for effective and influential social movements, but not all movements are successful in this regard. This article will explore the intersections of media mobilization and diversity strains as may be relevant to movement resonance.

Notably, the American Nonhuman Animal rights movement is dominated by middle-class white women [3,4,5]. The reasons for this are complex. The low level of African American participation, for instance, has been speculated by some to be a consequence of social disadvantage [6], cultural barriers [5], and ongoing trauma from historical experiences with violence and discrimination that creates discomfort with insensitive trans-species comparisons [7]. It may also result from historical constructions of “whiteness” as an indicator of compassion and “Blackness” with an inability to empathize with others or engage humaneness [8]. Early reformers working in an era of abolition positioned concern for other animals as a trait that was inherent to whites but impossible for people of color, a characteristic that would be used to legitimize systemic racism. Limited African American participation is sometimes thought a consequence of off-putting tactics which are rounded in racial insensitivities, as well as the general failure of Nonhuman Animal rights agendas to resonate with communities of color [9,10]. 1 Many anti-speciesist and vegan activists of color have worked to ameliorate this disconnect [11] by establishing historical connections to veganism, challenging the colonized animal-based diet [4], increasing access to and knowledge about healthy vegan foods [12,13], 2 and exploring similarities in experiences of oppression [16,17,18]. Despite these important connections, Harper [4] observes that veganism and Nonhuman Animal rights are routinely represented as a “white thing”.3, 4 She also criticizes the body image idealized by Nonhuman Animal activism and lifestyle as conspicuously thin and thus potentially ostracizing to ethnic body types.

Intimately connected to these racial disparities, the connections between gender identification and anti-speciesist imagination have also been explored. Some have pointed to similarities in subjugation for women and other animals, for instance [22,23], as well as the high numbers of women in Nonhuman Animal activism [24,25,26]. Extending these relationships, others have noted increasing sexualization in the media that simultaneously normalizes and promotes the consumption of feminized bodies, both human and nonhuman [22]. The sexualization of women (white women in particular) has been adopted as a tactic by major Nonhuman Animal rights organizations to “sell” veganism, a trend that is sparking strong criticism from some [24,26,27,28]. Women and Nonhuman Animals, it is argued, are sexualized, objectified, and dehumanized to facilitate their indiscriminate consumption by society’s privileged, and the Nonhuman Animal rights movement paradoxically exploits this connection to promote nonhuman liberation and to recruit participants [29].

Much of this work on race, gender, and sexualization has emerged as a critical response to the problematic representation (or lack of representation) in mainstream vegan and Nonhuman Animal rights media. Harper [3] illustrates this shortcoming:

For example, a demographic measure of One Green Planet contributors indicates that 90% of the 137 featured authors present as white. 5 Likewise, of 67 Animal Rights Zone podcast guests, 93% appear to be white-identified. 6 Indeed, the Nonhuman Animal rights movement might be said to abide by post-racial epistemologies that, as Harper [3,4] suggests, are insufficient in recognizing the very real consequences of socially created racial ascriptions: “My critique is that there are those (white and non-white) who believe ‘race is a feeble matter’ in animal rights activism. Such people are producing and practicing their own ‘post-racial’ epistemologies and praxis of AR/VEG ‘cruelty free ethics’” [3] (p. 17). Adding to this, Adams [22], Gaarder [24], and Wrenn [29] have suggested that the movement also exploits gender inequality in an effort to advance Nonhuman Animal rights.Popular vegan-oriented literature in the USA […] [does] not deeply engage in critical analysis of how race (racialization, whiteness, racism, anti-racism) influences how and why one writes about, teaches, and engages in vegan praxis and ultimately produces vegan spaces to affect cultural change (p. 8).

The apparent lack of race and gender consciousness in the Nonhuman Animal rights movement is a problem that should be a concern to those agitating for species justice in particular, but also for those working for social justice in general. Inequality reproduced in social movement media may have serious implications for coalition-building in social justice efforts. One magazine included in our sample has been cited as an example of such problematic representations:

Though class is not specifically explored in this study, it is a variable that very often intersects with gender, race, and body size. Implicit class representations in social movement media may also work to prevent strategic alliances among left-leaning movements. For these reasons, inequality in movement-produced material is incompatible with social justice goals and is also detrimental to necessary coalition-building.Though VegNews surely has its largely upscale market and audience in mind, the magazine does little to effectively counter the prevailing notion of veganism as the exclusive practice of upper-class, new-agey “bourgies”, and it does little to promote solidarity or affinity based anything beyond buying cool “green” stuff [30] (p. 136). 7

This article seeks to address the manifestation of race and gender in American social movement media, specifically looking at the Nonhuman Animal rights movement and comparing it to the similar movements: the women’s rights movement and the gay rights movement, as both the women’s rights movement and gay rights’ movement have shared histories of homogeneity and exclusion [31,32,33]. The Nonhuman Animal rights movement was chosen as it has been relatively understudied in the social sciences and recent developments in intersectionality perspectives in its ranks make this research especially timely. The comparison with other leftist movements will be helpful in ascertaining the significance of the findings. Beyond the rough similarities in profile, the comparison movements were chosen based on availability of regular magazine publications that feature human subjects (we had difficulty locating a suitable sample from the environmental movement, for instance).

The findings could illuminate the possibility that social movement media mobilization is hindering resonance and response from some marginalized populations by excluding them from media representations. We expect that the findings will inform Harper’s observation of a superabundance of thin, white women in Nonhuman Animal advocacy media spaces. The Nonhuman Animal rights movement may not just reflect, but also reinforce and cultivate a largely female-identified and white constituency with a problematic emphasis on thinness and sexualization. This study does not investigate the actual influences this media may be having on audiences (nor is it framed to account for trans or agender visibility), but it does act as a starting point for future research. Comparing anti-speciesist media to feminist and queer media will allow us to differentiate the Nonhuman Animal rights movement as either unique or comparable in its representations. That is, whether or not the Nonhuman Animal rights movement is an outlier or simply part of a larger social movement trend could be evidenced in the study’s outcome.

While investigating how feminist and queer social movement media impacts the demographic makeup of their constituencies is beyond the scope of this study, we will offer some brief suggestions. Specifically, we speculate that social movement media mobilization is, to some degree, responsible for reproducing an identity inclusive of a specific demographic. This could seriously hinder any social movement interested in attracting a diverse participant base. It may also be a concern to a social movement that desires to dismantle social inequalities and purports to value intersectionality.

2. Literature Review

Social movements rely heavily on the media to increase visibility [34], extend claims-making, and to recruit participants [35,36,37]. Through media representations, movements can foster a group identity and all-important solidarity [38]. Unfortunately, the usefulness of media representation is often undermined by considerable bias that often works to the movement’s disadvantage. The media’s coverage of a movement is largely dependent upon political context and a myriad of other variables such as type of protest, size of protest, and fickle media attention cycles. Not all movements are likely to receive coverage equally, if they receive any at all [2,39,40,41].

To some extent, movements are able to circumvent media bias by promoting their own media. Online entrepreneurship, for example, offers movements more freedom in recruitment and some control over how their organizations and claims are viewed [42,43]. As with those representations outside the movement’s control, the media that is movement-controlled is also vital for volunteer recruitment and other mobilization efforts.

As an agent of socialization, the media is important in influencing social behaviors and attitudes. This is because media works to “[…] maintain boundaries in a culture” [44] (p. 225). Modeling theory, for instance, posits that individual action can be guided through observing the normalized and institutionalized behavior of others [45]. It is thought that, through exposure to the media, individuals and groups absorb norms and values, appropriate behavior, and identity. Media, however, is generally constructed to reinforce hegemonic powers. Indeed, the media tends to reflect dominant culture at the expense of oppressed groups [46]. As one example, the National Association for Multi-Ethnicity in Communications [47] reports that ethnic minorities and women are still significantly underrepresented as writers, managers, executives, and other media producers.

In fact, the underrepresentation of minorities in the media has been heavily documented. Early research finds that Black appearances constituted less than 9% of prime time television programming. Cross-racial interactions constituted less than 2% of that time and generally displayed less intimacy and less shared decision-making [48]. More recent studies find that representation for African Americans has improved, but whites are still overrepresented while other minorities continue to be underrepresented and negatively depicted [49,50,51]. In addition to this failure to diversify representations, the media often fails to adequately cover issues of racism in content as well, sometimes to the effect of impeding productive discourse [52]. These societal trends provide the context for social movement activity. It is not a stretch to suppose that movements may be replicating social inequality already saturating media spaces here described.

Media can perpetuate prejudice against oppressed groups by exaggerating cultural differences and depicting negative portrayals [45,46,53]. This can jeopardize the self-concepts of minority children [54] and their mental health in general [55]. On the other hand, as the media increases in sophistication and becomes more sensitive to a public distaste for degrading ethnic images, it has the potential to overcompensate and create an unrealistic image of success which dilutes real social issues [56]. Indeed, vegan feminist Aph Ko [57] has taken issue with this problematic countermeasure in the Nonhuman Animal rights movement whereby tokenized images of Black and Brown persons are used superficially to illustrate narratives that essentially remain white-centric. “All too often”, she explains, “diversity discourse is used as an uncritical way to satisfy our culture’s desire to see minorities in predominately white-dominated fields without changing the actual white framework”. This process can lead to the erasure of difference and the replication of racism.

This review is not to suggest that audiences have no agency in their relationship with media. Certainly, viewers are frequently active participants in what they consume and interact with. For one, the ability to identify with the subject matter and to experience a feeling of similarity to those demographics represented can attract an audience. This attraction or detraction is one space for the audience to engage agency. So, in addition to theories of modeling and observational learning, it is helpful to recognize that audiences are not passive consumers. Instead, audience members are active participants in their media experience. Social cognitive theory, for example, sees social behavior as a product of cognitive and personal factors working reciprocally with environmental factors [58].

Thus, if some degree of agency in media consumption is recognized, an increase in positive and realistic representations of a movement’s diverse demographic would be needed to improve resonance. If an audience has the power to tune out or tune off, media producers would presumably be vested in accommodating consumer demand. Researchers explain: “Media have their greatest effect when they are used in a manner that reinforces and channels attitudes and opinions that are consistent with the psychological makeup of the person and the social structure of the groups with which he or she identifies” [46] (p. 44). For social movements, this could mean the self-produced media that reflects a limited demographic could be boxing in a limited demographic. These boundaries could not reasonably be expected to expand beyond that catered identity without some media cooperation. For example, one Hollywood diversity study finds that programming that features more diverse actors and writers is more popular, but the programs are “[…] nonetheless woefully underrepresented […]” [59]. Social movements, then, would probably not be advantaged in presuming their audiences to be passive recipients; a social movement’s audience, like any other, can pick and choose what it will tune into.

In spite of this audience agency, the media nonetheless both reflects and reinforces social attitudes, behaviors, and identities. A social movement concerned with social justice has good reason to be concerned with the social consequences of the media it produces. Media constructs a social reality and acts as an interpretive package for the public by giving meaning to social issues [1]. This not only pertains to racial categories and stereotypes, but also to gender roles. For example, women’s homemaker role is emphasized in commercials for domestic products (like vacuums and air fresheners) that overwhelmingly depict women as the consumers. Commercials for household goods (like refrigerators and tools), on the other hand, consistently underrepresent women [60]. In the world that much of the mass media presents, women’s subservient place is clear.

Another such trend is the increasing sexualization of women in the media [53,61]. This pattern is thought problematic because media could foster anti-feminist attitudes and increase aggressive behavior toward women [62,63,64,65,66,67]. Furthermore, the media’s glorification of thin bodies and its sexualization of women is linked to increased body dissatisfaction and decreased self-esteem [68,69,70,71]. Weight discrimination is also linked to hiring and promotional discrimination in the workplace and lower overall earnings, especially for women [72,73]. Hence, a thin and sexualized identity is perpetuated for women largely in the service of their societal devaluation. Social movement media that engages in the sexualization of women and the normalization of thinness might actually be contributing to inequality. If countering inequality is integral to that movement’s goals, as is true of the movements explored in this study, then accommodating these harmful norms in movement media could be particularly contradictory and problematic.

Certainly, some producers acknowledge the benefits to challenging stereotypes and privilege in media. Many advertisers attempt to increase their resonance by actively targeting minority populations, which in turn, has increased media multiculturalism. Social movement media operates similarly to that of advertising because it is generally intended to gain support and financial contributions from its audience. Therefore, it would presumably be advantageous to social movements to target marginalized demographics as well. Such a tactic would be in the interest of increased multiculturalism as a social justice matter, but, as a practical matter, it would also present greater potential for a movement’s frame resonance.

3. Methods

This study examines the demographical frequencies of some readily identifiable diversity indicators—race, gender, body type, and sexualization—in a sample of magazines representing some of the more prominent leftist movements. To accomplish this, the Nonhuman Animal rights movement, the feminist movement, and the gay rights movement are compared. The movements were chosen based on their similarity in justice-based, egalitarian claims-making, and their apparent interest in or tendency toward inclusivity. Other movements, such as the Black liberation movement and the environmental movement, might also have been useful to the study, but were not included due to restrictions in available or suitable sample material, but also in the interest of keeping the sample size manageable. The unit of analysis for this study is the human subject as depicted on covers of two major social movement publications from each of the three movements. The statistical analysis was conducted using SAS software. The questions proposed are considered in two parts: in regard to the sexualization of the magazine cover subjects, and in regards to the representation of gender and racial groups among the three movements. A more sophisticated content analysis exploring the content of these magazines could prove insightful. However, for the exploratory purposes of this study, we have chosen to focus specifically on covers under the assumption that the covers are designed to grab attention and quickly convey a specific message and image to the public.

3.1. Profile of Samples

People become vegan for all manner of reasons [5]. Subsequently, this study focuses on Nonhuman Animal rights rather than veganism exclusively. To represent this movement, we have analyzed PETA’s Animal Times (circulation of approximately 350,000) and VegNews (circulation of 76,000). Animal Times was selected as a representation of Nonhuman Animal rights outreach and movement culture, as PETA is one of the largest and most well-known organizations; VegNews is included as a representation of “normalized” vegan living. Indeed, because veganism is so intertwined with Nonhuman Animal rights, the behaviors of VegNews (the only mainstream vegan magazine at the time of this writing with a circulation of 76,000) should have implications for Nonhuman Animal liberation mobilization. Of note, the first two years of VegNews (2000–2001) and a number of issues in the years following were specifically related to Nonhuman Animal liberation and not the vegan lifestyle alone, thus speaking to its underlying anti-speciesist framework. Other magazines were not considered because they failed to regularly include human subjects on their covers. 8 Compassion Over Killing’s Compassionate Action, VIVA! UK, and the Humane Society of the United States’ All Animals, for example, feature mostly Nonhuman Animal subjects on their covers. Vegetarian Times, on the other hand, primarily features food.

For the feminist movement, we sampled the covers of Ms. Magazine and BUST Magazine. Considered a “landmark institution” in women’s rights, Ms. has been in publication since the 1970s and represents the “second wave” feminist movement. It currently has a circulation of over 100,000. BUST is a newer publication and is reflective of a more contemporary generation of feminists, often those who identify as “third wave”. We specifically chose representatives of both waves to gain a more comprehensive look at a highly fractured movement. Ms. has a long history in the field, but BUST is a somewhat more modern magazine, active only since 1993 and catering to a younger demographic.

Representative of the gay rights movement, we chose Equality (published by the Human Rights Council) and The Advocate. Equality was selected because it is published by the largest gay rights organization in the United States, equivalent in size and structure to the Nonhuman Animal rights movement’s PETA. The HRC bills it as the largest LGBT magazine in circulation. The Advocate was selected because it is has a long history of publication (since the 1960s) and is advertised as world’s leading gay and lesbian advocacy publication. The Advocate has a circulation of almost 200,000.

3.2. Dataset

Published four times a year until 2010 (and three times a year from 2011), there are 47 covers of PETA’s Animal Times between Spring 2000 and Issue 4 of 2012. Usually published six times a year, 9 there are 129 covers of VegNews Magazine beginning with July/August 2000 and ending with November/December 2012.

Ms. Magazine was published six times a year between 2000 and 2001, four times a year between 2002 and 2004, three times in 2005, four times in 2006–2011, and three times in 2012. There were a total of 54 issues included in our sample. BUST Magazine was published four times a year until 2005, when it began to release six issues per year. There were a total of 60 issues included.

Equality was published four times a year between 2000 and 2012, so 52 issues were included in our sample. The Advocate’s publication varied considerably over our time span. It was published 25 times in 2000, 35 times in 2001, 24 times in 2002, 26 times in 2003, 24 times between 2004 and 2006, 23 times in 2007 and 2008, and 11 times between 2009 and 2012 for a total of 272 issues.

Data was located through three sources: (1) Some issues are available free online (as are some issues of Equality); (2) Some covers were available in the back issues page of the magazines’ websites; and (3) Those that could not be obtained online were obtained through our institutions’ library services. We were unable to locate several issues, which were coded as missing. 10

We excluded six issues of Animal Times, 24 issues of VegNews, 21 issues of Ms., 11 issues of Equality, and 20 issues of The Advocate because they failed to portray a human subject or a discernible human subject. 11 Animal Times, for example, often featured Nonhuman Animals, while VegNews often utilizes images of food. If, however, a nonhuman subject dominated the cover, but there was a thumbnail image featuring a human face; these human subjects were included. A few issues of The Advocate featured a dozen or so couples on the cover, all of which were coded individually. Regardless of scale, any human subjects depicted are presumed to be influential in shaping the magazine’s demographic identity.

These were not the only issues to arise when coding the covers. In one case, 12 a thumbnail image was reused on a subsequent cover and this was omitted. Another cover featured several equally prominent subjects with only one visible face; only the subject whose face was visible was coded. 13 Several covers featured a large image of a human subject whose face was not to the camera. Because they were the only subjects on the cover and we felt we could reasonably ascertain their race from skin and hair, we included those. One issue featured infants. In this case, only their race could be determined, but several other images featuring adult humans were on that cover, so infants were omitted while the other subjects were not. 14 Background subjects and cartoons were excluded, however very realistic drawings were included. In three issues, only a woman’s torso is pictured. 15 Because it was impossible to accurately code her race or degree of sexualization (according to the scale we have chosen), these images were omitted.

The final subject count came to 48 for Animal Times, 104 for VegNews Magazine, 69 for Ms., 64 for BUST, 109 for Equality, and 564 for The Advocate. Only one author coded the data, but a reliability check was performed on 10% of the sample with the second author resulting in a 71% agreement. The bulk of the disagreement resulted from racially ambiguous subjects and subjects that were on the border of sexualized and not sexualized. One androgynous-presenting subject resulted in disagreement as well.

3.3. Coding Schemes

3.3.1. Race and Gender

While race and gender are social constructions, and are therefore relatively subjective, an exploration into other content analyses of a similar nature did not uncover a coding scheme for either variable [51,61,74,75]. Therefore, we have depended on our personal socialization to discern race and gender. Race was coded as white, African American, Asian, Latinx, 16 other, or unknown/undetermined. Gender was coded as female-presenting or male-presenting. Transgender individuals and persons in drag were coded according to the gender they were presenting. 17 As there is no inherent order to gender or racial categorizations, a logistic model is not necessary. Instead, a two-way contingency table analysis was conducted for each variable against movement.

3.3.2. Body Type

We used Johnson’s [76] body type scale that divides bodies into five types: round bodies with excess body fat (endomorph), bodies with some muscle definition and also excess fat (endo-mesomorph), muscle-toned bodies with a lack of excess body fat (mesomorph), fit and thin bodies (ecto-mesomorph), and thin bodies with stringy muscles (ectomorph). Several subjects were coded as the default (ecto-mesomorph) if only their face was pictured (with no indication of facial fat) or their clothing covered up their body and it was not possible to detect if they were toned or not. The inability to gauge some non-thin body types on covers that feature only faces will limit the study. We analyzed under the presumption that the face is likely to indicate the presence of a round body type, but this approach could not be said to be fully valid or reliable.

3.3.3. Sexualization

To determine degree of sexualization, we draw on Hatton and Trautner’s [6] coding scale that rates images as not at all sexualized, sexualized, or highly sexualized. 18 Their system entails a 23 point additive scale with 11 separate variables: clothing/nudity; touch; pose; mouth; breast/chest, genitals, and buttocks; text; head vs. body shot; display of sex act; and sexual role play. The total of points received indicates the level of sexualization in the image.

Depending on the amount of nudity, a cover subject could score between 0 and 5 points. Here, 0 indicates unrevealing clothing; 1 indicates slightly revealing clothing (such as shirts with low necklines or exposed arms); 2 indicates somewhat revealing clothing (demonstrated by exposed midriffs); 3 indicates highly revealing and/or skin-tight clothing; 4 indicates swimsuits and lingerie; and 5 indicates no clothing at all. Images that showed subjects from the chest up with an indication that the person was not wearing clothes were coded as 5.

The depiction of touch was also used as a marker of sexualization, with subjects scoring between 0 and 3 points. Those subjects neither touching nor being touched scored 0, those engaging in casual touching scored 1, those engaging in provocative touching scored 2 (lifting one’s shirt, for example), and those engaging in explicit sexual touching scored 3. The Hatton and Trautner study intended the touch scale to refer to human subjects touching themselves or other humans, but we have extended this variable to include the touching of other animals as well.

Based on the subject’s pose, the individual could score between 0 and 2 points, with 0 indicating a nonsexual pose; 1 indicating a slightly suggestive pose (including raised arms, leaning, or sitting); and 2 indicating an overtly suggestive pose. The subject’s mouth is also examined on a scale of 0–2, with 0 indicating a mouth that does not suggest sexual activity; 1 indicating a slightly suggestive mouth (including parted, non-smiling lips); and 2 indicating an overtly suggestive mouth. The breasts/chests, genitals, and buttocks of subjects were also examined on a scale of 0–2 with 0 assigned when body parts were either not visible or not the focal point; 1 assigned when one or more body part was emphasized; and 2 assigned when that body part was the central focus.

Text was analyzed on a scale of 0–2 when text is directly related the subject. If unrelated to sexuality, the image was scored zero. If it was in some way sexually suggestive, for example, “On Fire: Joaquin Phoenix today’s hottest veg celebrity” (VegNews Magazine, Issue 40), it scored 1. Images would be scored 2 if an explicitly sexual reference was made, but no images met this criterion. Body shots, which Hatton and Trautner have argued to be more sexualized, scored 1 point, whereas headshots scored none. Sex acts and sexual role playing were included in our analysis as part of the Hatton Trautner methodology, but none of our images applied. According to Hatton and Trautner’s coding scheme, the scores from these 11 categories should be tallied to determine overall sexualization. Images that scored 0–4 points were labeled nonsexualized, those that scored 5–9 were labeled sexualized, and those that scored 10 or more points were labeled as hypersexualized.

Two categorical models were built to measure the difference in sexualization of subjects. The independent variables (movement, race, gender) are all nominal variables, while the dependent variable (sexualization) is an ordinal variable. Therefore, a logistic model is most appropriate, as it models an ordinal variable as a function of one or several predictors. In this case, it was used to predict the probability of magazine cover subjects—that of varying races, genders, and representing three different movements—being not at all sexualized, sexualized, or very sexualized. The first of the two models established a baseline for comparison; sexualization as a function of gender and race. The second model built on those results, with movement added to determine its unique contribution, if any, to the variability in sexualization of the magazine models.

4. Results

4.1. Gender

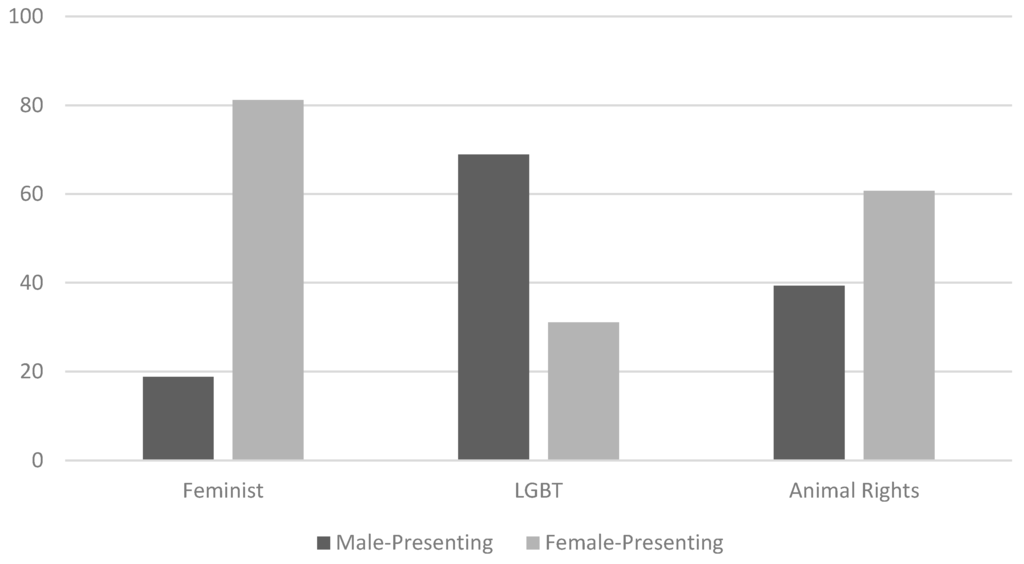

The contingency table analysis for association between gender and movement were significant (p < 0.001). That is, there are significant changes in the representation in gender associated with the different movements. Figure 1 illustrates where those differences arise: the gay rights movement predominantly used male-presenting models in the sample of covers studied (68.9%), while the Nonhuman Animal rights and feminist movements used predominantly female-presenting models (60.7% and 81.2%, respectively).

Figure 1.

Distribution of Gender.

4.2. Race

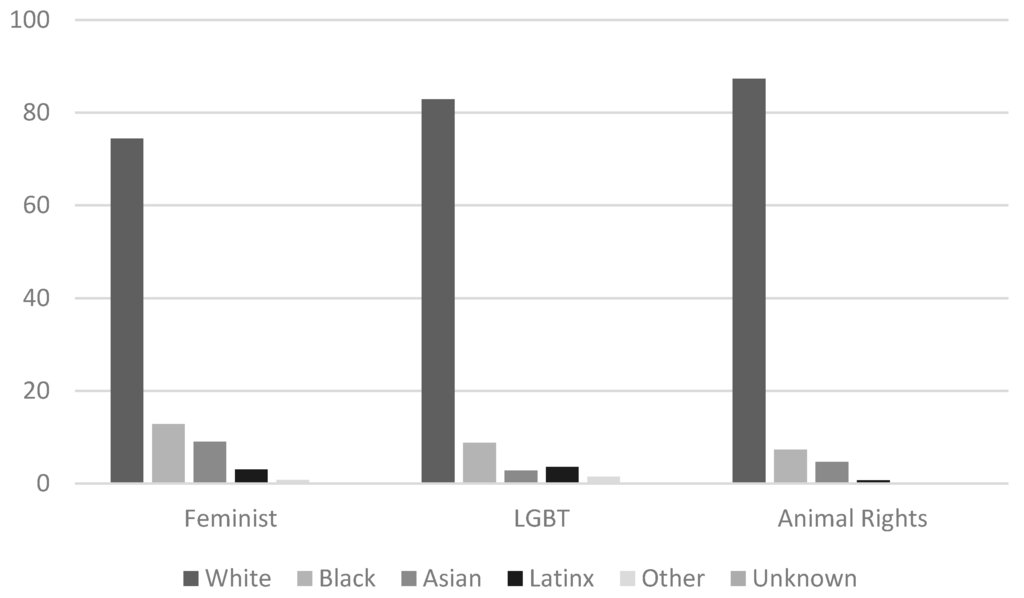

After combining human subjects of unknown and undetermined race with “other”, a chi-squared goodness of fit test including all 956 subjects from the three movements was conducted to determine whether the racial makeup of the images is the same as that of the US population [77]. The test was significant (p < 0.0001), indicating that the models were not representative of the population at large. Figure 2 demonstrates that white models are over represented in the sample, relative to the population, while the other races are underrepresented to varying degrees. The test for significant association between race and movement was significant (p = 0.0139), indicating that there are non-random changes in the representation of different races across the different movements. The distributions presented in Figure 2 illustrate where those differences arise: while whites and African Americans are represented most often in each of the movements in fairly consistent proportions, the ordering of Asians and Latinx of color in the three movements varies, as do their respective proportions across movements. Nonetheless, the Nonhuman Animal rights movement’s media does lay claim to the highest percentage of white subjects at 87.3%. This frequency is 4.4 percentage points higher than the gay rights movement media, and 12.9 percentage points higher than the feminist media.

Figure 2.

Distribution of Race.

In two cases, African Americans were underrepresented. African Americans comprise approximately 13% of the American population [77], but only 8.8% of the gay rights movement media sample and only 7.3% of the Nonhuman Animal rights sample. The feminist movement was relatively representative at 12.8%. About 5% of the American population is Asian, meaning that the 9% frequency for Asians in the feminist sample’s is somewhat over-representative, the Nonhuman Animal rights 4.7% frequency is somewhat representative, while the gay movement’s 2.8% frequency is somewhat lacking. Although Latinx persons comprise 17% of the population, they were seriously underrepresented in all three cases. The gay and feminist samples included about 3% Latinx subjects of color, while the Nonhuman Animal rights movement featured Latinx of color in less than 1% of the sample covers.

4.3. Sexualization

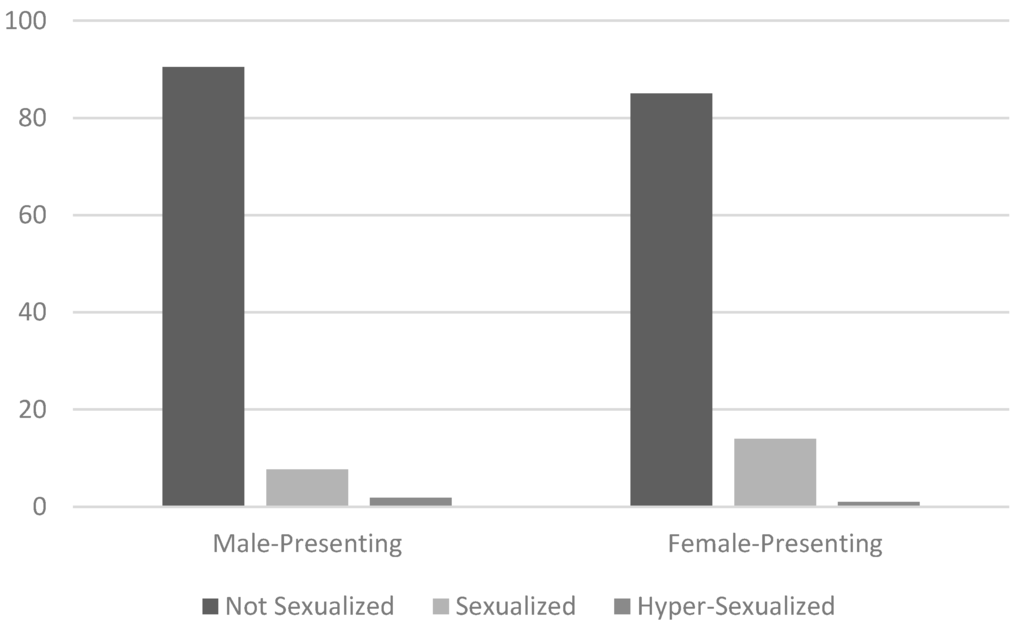

All three movements featured comparable levels of sexualization: 15.8% of the feminist sample featured sexualized subjects (an additional 0.75% were hypersexualized), 9.06% of the gay rights sample was sexualized (an additional 1.63% were hypersexualized), and 11.3% Nonhuman Animal rights subjects were sexualized (an additional 1.3% were hypersexualized). The initial model of sexualization vs. gender and race indicates that there is a significant difference in sexualization between women and men (p = 0.0139). The estimated odds ratio of sexualization for comparing male-presenting models to female-presenting models is 0.609, indicating that female-presenting models have lower odds of being sexualized than do male-presenting models (Figure 3). Race was not a significant predictor of sexualization (p = 0.6830), so it was removed from the subsequent model. To test for differences in sexualization due to movement, over and above that due to gender, another model was developed. Movement was not a significant predictor of sexualization (p = 0.6242), though gender remained significant (p = 0.0496), with an estimated odds ratio for females to males of 0.652.

Figure 3.

Distribution of Sexualization.

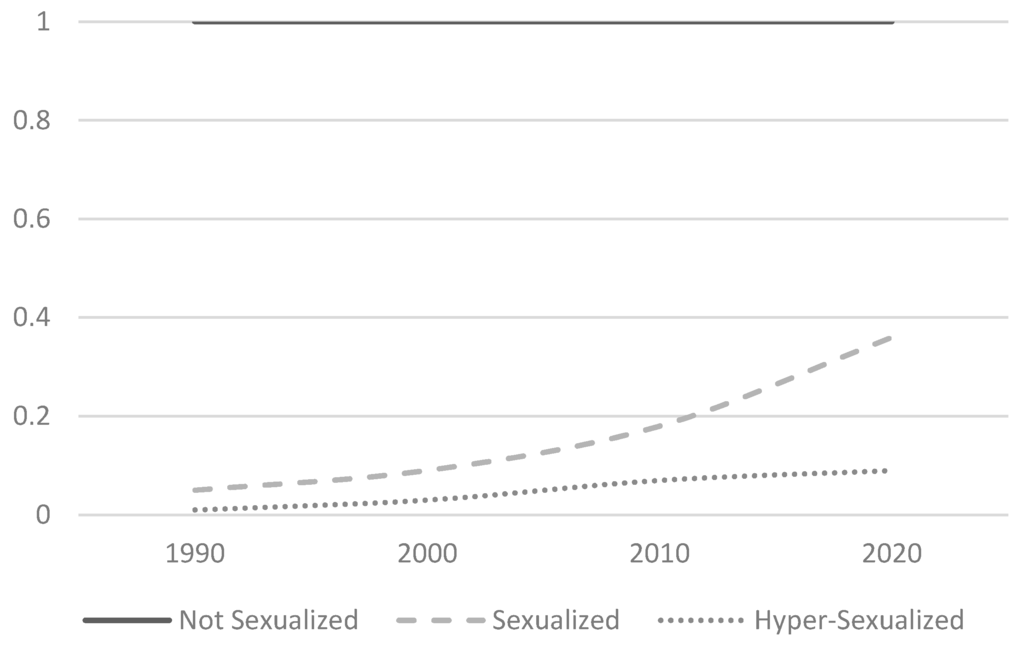

There is some evidence of increase in sexualization over time (Figure 4). The Spearman correlation between sexualization and publication year is significant (p = 0.0004), but relatively weak (r = 0.113); the large sample size is likely a driver of its significance. Modeling the relationship with a proportional odds model to determine probabilistic differences in the levels of sexualization over time likewise found a positive trend (p = 0.0032). The estimated odds ratio, regardless of movement, indicates that each additional year increases the likelihood of sexualization of a magazine cover model by a factor of 1.09. A plot of the relationship between the levels of sexualization and time supports the weak Spearman correlation and low odds ratio.

Figure 4.

Sexualization over Time.

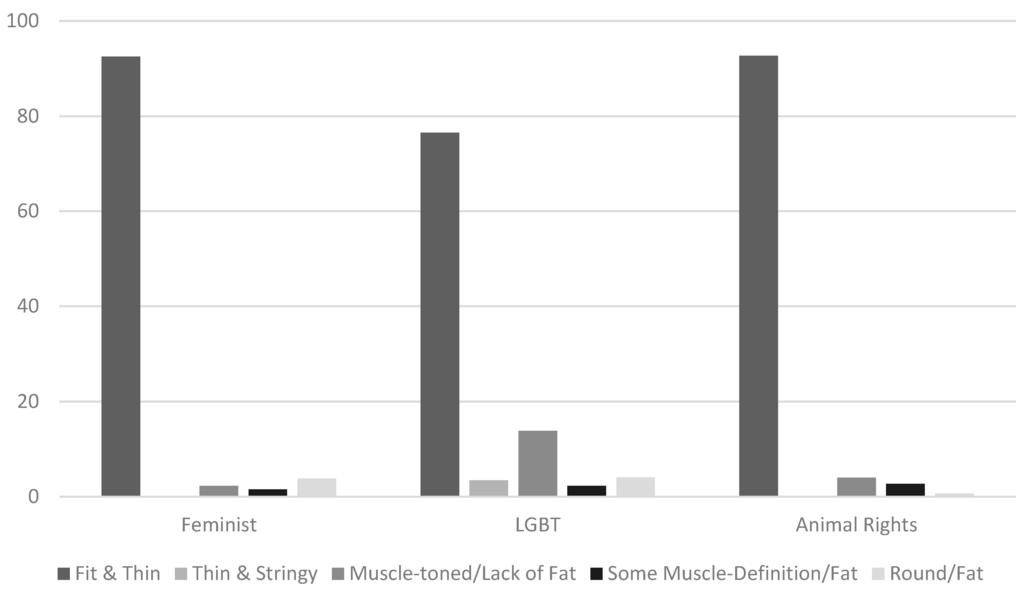

4.4. Body Type

There was a significant difference in body type representation across the three movements (p < 0.0001), though all three movements had a majority of fit and thin models on their covers (Figure 5). The gay rights magazines had a greater diversity of body types in their models, including more muscle-toned models and models of size than either of the other two movements; 76.5% of these models were of the fit and thin body type, and the remaining quarter were fairly evenly distributed among the remaining types. The feminist and Nonhuman Animal rights movements (92.5% and 92.7%, respectively) each had over 90% of the cover models fall within the fit and thin body type representation, with the remaining body types ranging from muscle-toned to round. The Nonhuman Animal rights sample was the least likely to include subjects of size.

Figure 5.

Distribution of Body Type.

5. Conclusions

In representation of gender, the Nonhuman Animal rights movement more closely resembles that of feminist media, with more women than men represented. However, it also resembles queer media in that it presents gender ratios that do not closely match actual activist ratios. Queer media in our sample disproportionately features male-presenting subjects, which would inaccurately downplay the presence and involvement of lesbians. The relatively few number of women presented in gay rights magazines may speak to a history of lesbian exclusion in the movement [78] and lesbian underrepresentation in gay media [31,79]. Though the vegan media sample demonstrates higher than average numbers of women, these numbers do not come close to the actual presence of women in Nonhuman Animal rights spaces. This likely relates to patriarchal norms in the movement which position men as highly visible leaders and women as caregivers, organizers, or other support providers expected to remain behind the scenes [24]. Relatively few men were pictured on the feminist magazines, which may be indicative of the feminist goal of creating a woman-normative space that resists patriarchal domination. To be sure, the positive and dignified representation of women, especially as leaders and role models, is important in a patriarchal society; however, failure to include more male-presenting subjects may be hindering the feminist movement’s ability to attract male-identified allies. Alternatively, the feminist sample featured considerable sexualized subject matter, particularly BUST. This may reflect the third-wave focus on sex positivity, as well as the patriarchal co-optation of feminist spaces. These pressures sometimes increase the emphasis on sexual liberation to the effect of sexualizing feminism [80].

In representations of race, all movements fail to adequately represent minorities to some extent, though the feminist sample was most favorable to African Americans and Asians. All movements seriously underrepresented Latinx of color. The results of the gay rights sample are consistent with a long history of the gay media excluding people of color [31]. The Nonhuman Animal rights sample was the most white-centric, with almost nine out of ten subjects appearing to be white-identified.

While some of Hatton and Trautner’s sexualization variables did not surface in the data (the performance of a sex act and sexual role play), indicating potentially lower levels of sexualization in social justice magazines as compared to some of the mainstream media they analyzed, the substantial number of images that did score as sexualized is relevant. Despite its focus on sexual orientation and sexual liberation, queer media in our sample ranked lowest in sexualized subjects. Because the gay media is known to underrepresent female-presenting subjects and these subjects are more likely to be sexualized, this is understandable. The gay rights sample did, however, demonstrate the highest percentage of hyper-sexualization among sexualized subjects. This sexualization may be concerning given research which indicates that gay men are also susceptible to self-objectification, body shame, and restricted eating as a result of existing in a subculture that prioritizes physical appearance [81]. Probably reflecting third-wave “sex-positive” trends in feminism, our feminist sample ranked the highest in sexualization. Nonhuman Animal rights fell in between the two, though all three movements were relatively comparable in sexualization (levels ranged between 11% and 17%). Sexualization appears to be growing more prevalent across time, though only minimally and perhaps due to the large sample size. This trend does correspond with other findings regarding the increase of sexualization in the media [61,82,83]. It is also important to mention here that PETA, the publisher of Animal Times, is notorious for sexually objectifying the subjects in its media [24,27,28], which may have inflated the prevalence of sexualization in the results.

Regarding body type, the predominance of thinness in our samples may reflect the publishers’ interest in portraying a conventionally desirable body image. This may be intentionally cultivated by the gay rights movement following stereotypes of gays and lesbians as weak or ill. For the Nonhuman Animal rights media, the predominance of thinness may also be a response to perceived healthiness or unhealthiness of vegetarian and vegan diets that are often associated with the movement. Furthermore, Johnson [76] finds that negative personality ascriptions are associated with body types that “deviate” from thinness. Understandably, our sampled magazines are likely hoping to portray their respective movements as positively as possible. Though, in doing so, they create an unrealistic body type ideal. They also foster an identity that can potentially alienate other body types, specifically impacting people of color. Women of color often exhibit beauty aesthetics based in their own cultural legacies, or even nurture embodied difference as a form of resistance [84]. As a result, Black and Brown bodies can be pathologized or experience stigma in a thin-privileging media space.

To summarize, the Nonhuman Animal rights media in our sample, when compared to other leftist social justice movements, appears to be somewhat more gender-balanced, somewhat more white-centric, moderately sexualized, and less diverse in body type representations. Nonhuman Animal rights, women’s rights, and gay rights media could be reflecting a perceived demographic or they may be facilitating an idealized demographic. In utilizing media spaces, social change actors must overcome societal biases that tend to favor hegemonic status quo and invisiblizes social movement claims-making and activities. Social movements may be exacerbating this disadvantage in fostering their own bias. The media is essential in movement recruitment and claims-making: it constructs a social reality, and shapes public opinion. If a social movement’s own media representations are creating a limiting identity, they, alongside mainstream media, may be just as responsible for biased representation.

One major limitation in this study is the visibility of the magazines utilized. We selected magazines based on their accessibility to the public, and we chose covers because of their role in marketing the magazine’s theme and purpose expeditiously to passing customers. Some non-profit affiliated magazines, such as Animal Times and Equality, are issued only to subscribing members with only a few select issues available for online viewing and thus may be less influential to the public. For the most part, readers would have to subscribe to see the magazines, so these magazines may be more reflective of their existing demographic and would wield less power in advertising. However, PETA and HRC’s publications are far from top secret as they are advertised and shared, meaning that the identity maintained through these covers likely help foster a particular constituency. VegNews, Ms., BUST, and The Advocate on the other hand, are publically available publications. Yet, they, too, are limited in their reach because they cost a nominal fee and they are distributed in very specific sale locations. VegNews, for example, is a specialty magazine with a focus on an alternative diet and lifestyle, and tends to be offered in natural foods grocers. Natural foods grocers, in turn, tend to cater to middle class whites who are more likely to be privileged with the income and access for healthful shopping.

Nonetheless, as dominant representations of Nonhuman Animal rights culture, the white, feminized identity that is nurtured by Animal Times and VegNews could undoubtedly reach beyond a simple reflection of their existing demographic and may actually begin to police that identity through the exclusion of others. It would also be interesting to ascertain what impact this movement-nurtured identity is having for the majority demographic in regards to how they relate to the marginalized. As Harper bemoans, a false consciousness about diversity (sometimes referred to as “color-blindness”) can shut down critical discussions about persistent discrimination within activist spaces (and society in general).

This study is also limited in the small, non-random sample size which cannot be wholly representative. Movements are large, diverse, and factionalized, meaning that the prominent magazines we chose will present a relatively biased view. Likewise, magazines represent only one form of movement produced media. Additional analyses that include other publications and other forms of media (commercials, websites, music, etc.) could broaden the scope of this study’s implications for social movement diversity.

The Nonhuman Animal rights media thus examined favors thin white women,19 more so than that of the feminist movement and the gay rights movement. However, other movements are also recreating similar problems that reflect stereotypes about their demographics. This study cannot speak specifically to the impact these demographic representations are having on potential recruits or existing activists, but it does offer an important starting point for future research into the relationships between social movement media and social movement success. Further research into viewer interpretations, minority experiences in the ranks, and movement motivations and goals regarding diversity would be beneficial to this topic.

Author Contributions

Author Corey Lee Wrenn both conceived and designed the study. Wrenn also conducted the content analysis and authored the paper. Author Megan Lutz contributed the statistical analysis, interpreted the statistical analysis, and acted as the secondary analyst in the coding reliability check.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix

Table A1.

Coding Scheme.

| Race | |

| 0 | White |

| 1 | African American |

| 2 | Asian |

| 3 | Latinx of Color |

| 4 | Other |

| 5 | Unknown/Undetermined |

| Gender | |

| 0 | Male-presenting |

| 1 | Female-presenting |

| Body Type | |

| 0 | Ecto-Mesomorph (Fit & Thin) |

| 1 | Ectomorph (Thin/Stringy Muscles) |

| 2 | Mesomorph (Muscle-toned, lack of fat) |

| 3 | Endo-Mesomorph (Some muscle definition/excess fat) |

| 4 | Endomorph (Round/excess fat) |

| Sexualization 20 | |

| 0 | Not at all sexualized (0–4) |

| 1 | Sexualized (5–9) |

| 2 | Highly sexualized (10–23) |

References

- Gamson, W.; Modigliani, A. Media discourse and public opinion on nuclear power: A constructionist approach. Am. J. Sociol. 1989, 95, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamson, W.; Croteau, D.; Hoynes, W.; Sasson, T. Media images and the social construction of reality. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1992, 18, 373–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, B. Race as a “feeble matter” in veganism: Interrogating whiteness, geopolitical privilege, and consumption philosophy of “cruelty-free” products. J. Crit. Anim. Stud. 2010, 8, 5–27. [Google Scholar]

- Harper, B. Sistah Vegan: Food, Identity, Health, and Society: Black Female Vegans Speak; Lantern Books: Brooklyn, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Maurer, D. Vegetarianism: Movement or Moment? Temple University Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Guither, H. Animal Rights: History and Scope of a Radical Social Movement; Southern Illinois University Press: Carbondale, IL, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, A. Should people of color support animal rights? Anim. Law 2009, 5, 15–32. [Google Scholar]

- Lundblad, M. Archaeology of a humane society: Animality, savagery, Blackness. In Species Matters: Humane Advocacy and Cultural Theory; DeKoven, K., Lundblad, M., Eds.; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 75–101. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey, C. We are what we eat: Feminist vegetarianism and the reproduction of racial identity. Hypatia 2007, 22, 39–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drew, A. Being a sistah at PETA. In Sistah Vegan: Food, Identity, Health, and Society: Black Female Vegans Speak; Harper, B., Ed.; Lantern Books: Brooklyn, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 61–64. [Google Scholar]

- VegNews Magazine. Available online: http://vegnews.com/articles/page/do?pageId=4438&catId=5 (accessed on 11 November 2015).

- Terry, B. Vegan Soul Kitchen: Fresh, Healthy, and Creative African American Cuisine; Da Capo Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Terry, B. The Inspired Vegan: Seasonal Ingredients, Creative Recipes, Mouthwatering Menus; Da Capo Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Williams-Forson, P. Building Houses out of Chicken Legs: Black Women, Food, and Power; The University of North Carolina Press: Chapel Hill, NC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Inness, S. Secret Ingredients: Race, Gender, and Class at the Dinner Table; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bahna-James, T.S. Journey towards compassionate choice: Integrating vegan and sistah experience. In Sistah Vegan: Food, Identity, Health, and Society: Black Female Vegans Speak; Harper, B., Ed.; Lantern Books: Brooklyn, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 155–168. [Google Scholar]

- Dunham, D. On being Black and vegan. In Sistah Vegan: Food, Identity, Health, and Society: Black Female Vegans Speak; Harper, B., Ed.; Lantern Books: Brooklyn, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 42–46. [Google Scholar]

- Spiegel, M. The Dreaded Comparison: Human and Animal Slavery; Mirror Books/I.D.E.A.: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Lowe, B.; Ginsberg, C. Animal rights as a post-citizenship movement. Soc. Anim. 2002, 10, 203–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inglechart, R. Modernization and Postmodernization: Cultural, Economic, and Political Change in 43 Societies; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Jasper, J. The Art of Moral Protest: Culture, Biography, and Creativity in Social Movements; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, C. The Sexual Politics of Meat: A Feminist-Vegetarian Critical Theory; The Continuum International Publishing Group, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, C.J.; Donovan, J. Animals and Women: Feminist Theoretical Explorations; Duke University Press: Durham, NC, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Gaarder, E. Women and the Animal Rights Movement; Rutgers University Press: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kemmerer, L.; Adams, C. Sister Species: Women, Animals, and Social Justice; University of Illinois Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Luke, B. Brutal: Manhood and the Exploitation of Animals; University of Illinois Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Deckha, M. Disturbing images: PETA and the feminist ethics of animal advocacy. Ethics Environ. 2008, 13, 35–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glasser, C. Tied oppressions: An analysis of how sexist imagery reinforces speciesist sentiment. Brock Rev. 2011, 12, 51–68. [Google Scholar]

- Wrenn, C. The role of professionalization regarding female exploitation in the Nonhuman Animal rights movement. J. Gender Stud. 2013, 24, 131–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, B. Making a Killing: The Political Economy of Animal Rights; AK Press: Oakland, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Chasin, A. Selling out: The Gay and Lesbian Movement Goes to Market; Palgrave: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, A. Women, Race, & Class; First Vintage Books: New York, NY, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Hooks, B. Ain’t I a Woman: Black Women and Feminism; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Vliegenthart, R.; Oegema, D.; Klandermans, B. Media coverage and organizational support in the Dutch environmental movement. Mobilization 2005, 10, 365–381. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, K.; Biggs, M. The dynamics of protest diffusion: Movement organizations, social networks, and news media in the 1960 sit-ins. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2006, 71, 752–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamson, W. Bystanders, public opinion, and the media. In The Blackwell Companion to Social Movements; Snow, D., Soule, S., Kriesi, H., Eds.; Blackwell Publishing: Oxford, UK, 2004; pp. 242–261. [Google Scholar]

- Sampedro, V. The media politics of social protest. Mobilization 1997, 2, 185–205. [Google Scholar]

- Roscigno, V.; Danaher, W. Media and mobilization: The case of radio and Southern textile worker insurgency, 1929 to 1934. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2001, 66, 21–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amenta, E.; Caren, N.; Olasky, S.; Stobaugh, J. All the movements fit to print; who, what, when, where, and why SMO families appeared in the New York Times in the twentieth century. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2009, 74, 636–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, J.; McPhail, C.; Smith, J. Images of protest: Dimensions of selection bias in media coverage of Washington demonstrations, 1982 and 1991. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1996, 61, 478–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, P.; Maney, G. Political processes and local newspaper coverage of protest events: From selection bias to triadic interactions. Am. J. Sociol. 2000, 106, 463–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, P.; Lichbach, M. To the Internet, from the Internet: Comparative media coverage of transnational protests. Mobilization 2003, 8, 249–272. [Google Scholar]

- Earl, J.; Schussman, A. The new site of activism: On-line organizations, movement entrepreneurs, and the changing location of social movement decision making. Res. Soc. Mov. Conflicts Chang. 2003, 24, 155–187. [Google Scholar]

- Shoemaker, P.; Reese, S. Mediating the Message: Theories of Influences on Mass Media Content, 2nd ed.; Longman Publishers: White Plains, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Dorr, A. Television and socialization of the minority child. In Television and the Socialization of the Minority Child; Berry, G., Mitchell-Kernan, C., Eds.; Academic Press: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1982; pp. 15–35. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, C.; Gutierrez, F. Race, Multiculturalism, and the Media: From Mass to Class Communication; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- National Association for Multi-Ethnicity in Communications. NAMIC and WICT Cable Telecommunications Industry Workforce Diversity Survey; NAMIC and WICT: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Weigel, R.; Loomis, J.; Soja, M. Race relations on prime time television. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1980, 39, 884–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, C. Images of women’s sexuality in advertisements: A content analysis of Black- and white-oriented women’s and men’s magazines. Sex Roles 2005, 52, 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastro, D.; Greenburg, B. The portrayal of racial minorities on prime-time television. J. Broadcast. Electron. Media 2003, 47, 638–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastro, D.; Stern, S. Representations of race in television commercials: A content analysis of prime-time advertising. J. Broadcast. Electron. Media 2003, 47, 638–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apollon, D.; Keheler, T.; Madeiros, J.; Ortega, N.; Sebastian, J.; Sen, R. Moving the Race Conversation Forward: How the Media Covers Racism, and Other Barriers to Productive Racial Disclosure; Race Forward: The Center for Racial Justice Innovation: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Coltrane, S.; Messineo, M. The perpetuation of subtle prejudice: Race and gender imagery in 1990s television advertising. Sex Roles 2000, 42, 363–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, G. The impact of television on the self-concept development of minority group children. In Television and the Socialization of the Minority Child; Berry, G., Mitchell-Kernan, C., Eds.; Academic Press: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1982; pp. 105–131. [Google Scholar]

- Spurlock, J. Television, ethnic minorities, and mental health: An overview. In Television and the Socialization of the Minority Child; Berry, G., Mitchell-Kernan, C., Eds.; Academic Press: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1982; pp. 71–80. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, H. Watching race: television and the struggle for blackness; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Koçieda, A. Understanding racism. Available online: http://veganfeministnetwork.com/resources/understanding-racism-101/ (accessed on 11 April 2016).

- Bandura, A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory; Prentice-Hall, Inc.: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt, D. Hollywood Diversity Brief: Spotlight on Cable Television; Ralph, J., Ed.; Bunche Center for African American Studies: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bartsch, R.; Burnett, T.; Diller, T.; Rankin-Williams, E. Gender representation in television commercials: Updating an update. Sex Roles 2000, 43, 735–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatton, E.; Trautner, M. Equal opportunity objectification? The sexualization of men and women on the cover of Rolling Stone. Sex. Cult. 2011, 15, 256–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalof, L. The effects of gender and music video imagery on sexual attitudes. J. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 139, 378–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lanis, K.; Covell, K. Images of women in advertisements: Effects on attitudes related to sexual aggression. Sex Roles 1995, 32, 639–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKay, N.; Covell, K. The impact of women in advertisements on attitudes towards women. Sex Roles 1997, 36, 573–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malamuth, N.; Check, J. The effects of mass media exposure on acceptance of violence against women: A field experiment. J. Res. Personal. 1981, 15, 436–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mundorf, N.; D’Alessio, D.; Allen, M.; Emmers-Sommer, T. Effects of sexually explicit media. In Mass Media Effects Research: Advances through Meta-Analysis; Preiss, R., Gayle, B., Burrell, N., Allen, M., Bryant, J., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 181–198. [Google Scholar]

- Ward, L. Does television exposure affect adults’ attitudes and assumptions about sexual relationships? Correlation and experimental confirmation. J. Youth Adolesc. 2002, 31, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubrey, J.; Stevens, J.; Henson, K.; Hopper, M.; Smith, S. A picture is worth twenty words (about the self): Testing the priming influence of visual sexual objectification on women’s self-objectification. Commun. Res. Rep. 2009, 26, 271–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groesz, L.; Levine, M.; Murnen, S. The effect of experimental presentation of thin media images on body satisfaction: A meta-analytical review. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2002, 31, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmstrom, A. The effects of the media on body image: A meta-analysis. J. Broadcast. Electron. Media 2004, 48, 196–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, S.; Hamilton, H.; Jacobs, M.; Angood, L.; Dwyer, D. The influence of fashion magazines on body image satisfaction of college women: An exploratory analysis. Adolescence 1997, 32, 603–614. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Puhl, R.; Andreyeva, T.; Brownwell, K. Perceptions of weight discrimination: Prevalence and comparison to race and gender discrimination on America. Int. J. Obes. 2008, 32, 992–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zagorsky, J. Is Obesity as dangerous to your wealth as to your health? Res. Aging 2004, 26, 130–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazell, V.; Clarke, J. Race and gender in the media: A content analysis of advertisements in two mainstream Black magazines. J. Black Stud. 2008, 39, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kean, L.G.; Prividera, L. Communicating about race and health: A content analysis of print advertisements in African American and general readership magazines. Health Commun. 2007, 21(3), 289–297. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, K. Impressions of personality bases on body forms: An application of Hillestad’s model of appearance. Cloth. Text. Res. J. 1990, 8, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Census Bureau. People QuickFacks 2012. Available online: http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/00000.html (accessed on 11 November 2015).

- Lindsey, L. Gender Roles: A Sociological Prospective, 5th ed.; Prentice Hall: Boston, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Dhoest, A.; Simons, N. Questioning queer audiences: Exploring diversity in lesbian and gay men’s media uses and readings. In The Handbook of Gender, Sex and Media; Ross, K., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: West Sussex, UK, 2014; pp. 260–276. [Google Scholar]

- Levy, A. Female Chauvinist Pigs: Women and the Rise of Raunch Culture; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Martins, Y.; Tiggemann, M.; Kirkbride, A. Those speedos becomes them: The role of self-objectification in gay and heterosexuals men’s body image. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2007, 33, 634–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graff, K.; Murnen, S.; Krause, A. Low-cut shirts and high-heeled shoes: Increased sexualization across time in magazine descriptions of girls. Sex Roles 2013, 69, 571–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichert, T.; Carpenter, C. An update on sex in magazine advertising. J. Mass Commun. Q. 2004, 81, 823–837. [Google Scholar]

- Van Amsterdam, R. Big fat inequalities, thin privilege: An intersectional perspective on “body size”. Eur. J. Women’s Stud. 2013, 20, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 1A reviewer has suggested that this disconnect could also stem from a long history of white supremacist brutality against Black communities via the use of dogs.

- 2Bryant Terry is a food justice advocate for communities of color; his activism is discussed in the cookbooks referenced. Food and cooking are integral to African American cultures of political resistance [14]. They have also been essential to feminist and environmentalist efforts [15].

- 3Although veganism and activism for other animals are often distinct, the two concepts are often used interchangeably. Most Nonhuman Animal rights efforts idealize veganism as foundational to anti-speciesist efforts, and the public tends to conflate the two. The Nonhuman Animal rights literature included in this study happens to be vegan-based (non-vegan magazine sources were not deemed suitable for analysis due to low numbers of human subjects). For these reasons, veganism will sometimes be used to reference Nonhuman Animal rights.

- 4The Nonhuman Animal rights movement is considered to be a “post-citizenship” movement [19]. Participants of post-citizenship movements generally advocate on behalf of others or for non-material values and morals. They also tend to be well-integrated and relatively privileged in their society [20,21]. This may partially explain why disadvantaged demographics are underrepresented in the Nonhuman Animal rights movement.

- 5This analysis was conducted in 2013 and was based on contributor avatars listed on One Green Planet’s website: http://www.onegreenplanet.org/channel/about-us. One Green Planet is an influential online webzine and community featuring many of the most prominent authors and activists in the movement.

- 6This analysis was conducted in 2013 according to the guests listed on the ARZone podcast page: http://arzone.ning.com/page/podcasts. Guests who made repeat appearances in more than one episode were counted once for each appearance. The regular hosts were excluded. ARZone is an academically-focused online community that also features the most prominent authors and activists in Nonhuman Animal rights mobilization.

- 7Vegan consumer items of convenience and comfort are, arguably, helpful in the transition to veganism and sustaining a vegan lifestyle. Torres’ critique, however, points to the problematic ways in which the consumer focus of veganism undermines its political capacity.

- 8It is worth considering that nonhuman subjects (who are less likely to present gender norms) could have an equalizing effect and may actually welcome underrepresented groups. Furthermore, nonhuman imagery is heavily utilized by the Nonhuman Animal rights movement to stimulate empathy and mobilization. This relationship between nonhuman cover subjects and propensity for participation would be worth exploring in future research.

- 9Three times in 2000, 10 times in 2001, 9 times in 2002, and 5 times in 2004.

- 10Bust Magazine (11); Equality (23); and The Advocate (6).

- 11For example, the Winter 2007 issue of Equality depicted a blurred face and an outreaching hand. Gender was undeterminable, and because the library scan was in black and white, the race of the subject was also unknown.

- 12VegNews 2001, January (4).

- 13VegNews 2001, February (5).

- 14VegNews 2001, May/June (8,9).

- 15VegNews 2004, September/October (39); 2004, January/February (41); 2008, January/February (59).

- 16This is the gender-neutral term meant to include trans and gender fluid persons.

- 17Admittedly, the framework of the analysis and its focus only on cover subjects makes addressing gender variance difficult; it also reinforces a limiting gender binary.

- 18Please see the original study for further explanation on how variables we’ve included were coded and why.

- 19Recall that the sample from the feminist movement features more women, but these women are more likely to be diverse in race and body type.

- 20See Hatton and Trautner’s [61] study cited in this manuscript for a full description of the sexualization coding scheme.

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons by Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).