Abstract

Plastic beads have recently become of importance in the lives of women with disabilities in Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo (DR Congo). Using a materialist approach that focuses on such specific items, this article deviates from most materialist approaches to disability that are focused on the built environment, medical objects, or assistive technology. Rather, the focus is on “things” (this term is to be understood as items being alive in meshworks of social relations) that are explanatory of disability, gender, and world formation or “making”. We show how the interplay of materials, gender, and disability results in acts of creation and performance, and involves an unfolding of life and orientation towards the future.

1. Introduction

Plastic beads (“perles” in French) have become part of the lives of a number of people with physical disabilities at CEPROMEFHA (Centre de Promotion Maman Efinole Femmes Handicapées), in Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo (DR Congo). During our fieldwork in Kinshasa, our interest turned to the particular phenomenon of women with disabilities being involved in crafts with the aim of securing income. The work involving the practice of beadwork captured our attention. We asked initial questions about the historical origins of these beads, the emplacement of the practice in the context of social networks, and the impact of such practices on disability. Beadwork is described as historically and socio-culturally situated (i.e., as temporal and contextual). We looked into the social processes that coincided with it, and became interested in a material approach to better understand it. What can plastic beads do, and how do they have an impact on disability?

We start from the idea that the things in the world that we shape also shape us. We examine how beads as part of material culture are interrelated with gender and disability identity in Kinshasa. We understand disability not only as a historical and socio-cultural construction, but also, and especially, as the momentary outcome of a relational process. Aspects of identity such as gender, ethnicity, and disability are considered to be not static or essential, but rather dynamic and ongoing [1,2], fluid [3], and performed [4]. Our point of departure is that disability is highly relational in the sense that disabled people are socially and otherwise embedded [5]. In other words, disabled people are related to things, to other people, to the environment, and to the world surrounding them. Both Butler’s and Grosz’s performative philosophy inspired our interpretation of “gender”. Butler, for instance, elaborates on a genealogy of women [4] and describes matter as “a process of materialization that stabilizes over time to produce the effect of boundary, fixity, and surface” [6] (p. 18). Elizabeth Grosz emphasizes a woman’s experience of her body as something specific and irreducible [7]. Moreover, bodies are not passive and not just the result of outside forces. In her work, Grosz refers to these processes as the “outside in” and “inside out” of the body [7]. “What we are is determined to a large extent, not by who recognizes us, but by what we do, what we make, what we achieve or accomplish” [8] (p. 88).

Alfred Gell [9] developed in his work the idea that people and things act upon each other (e.g., people move cars, but a car also acts upon people; equally a work of art “acts” on people). There is a body of research that examines how agency can be ascribed to both humans and objects. This has introduced an important argument against representationalism, based on a dichotomy between people and things, which we follow. In this article we also step away from dichotomies such as self-other, individual-society, and nature-culture. This move beyond representationalism and human-centric reasoning is currently discussed by several theorists, such as Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari [10] (rhizome, becoming, affect), Karen Barad [11] (materiality, agential intra-action), Tim Ingold [12] (habitat, lines and meshworks), and Nigel Thrift [13] (on flow, play, everyday practices, things, effectivity), amongst others. Barad and Ingold challenge the idea of agency as such, and also of meaning and matter as separate entities on an ontological level. Instead, they offer a relational ontology as a perspective. In her work, Barad [11] investigates a move towards a performative understanding of discursive practices. More precisely, Barad suggests a materialist and posthumanist reworking of the notion of performativity. She asks us to:

Acknowledge nature, the body, and in the fullness of their becoming without resorting to the optics of transparency or opacity, the geometries of absolute exteriority or interiority, and the theorization of the human as either pure cause or pure effect while at the same time remaining resolutely accountable for the role “we” play in the intertwined practices of knowing and becoming.[11] (p. 812)

What is more, according to Barad, “thingification—the turning of relations into “things”, “entities”, “relata”—infects much of the way we understand the world and our relationship to it” [11] (p. 812).

Ingold opposes the idea of materiality, as for him everything is part of the material world: the bodies-that-we-are, natural objects, artefacts, air, the weather, and plastic beads [12,14]. In an unfolding world “the properties of materials, regarded as constituents of an environment, cannot be identified as fixed, essential attributes of things, but are rather processual and relational” [12] (p.14). Ingold does not assign agency as such to things and people, but rather believes that:

Things are active not because they are imbued with agency but because of ways in which they are caught up in these currents of the lifeworld. The properties of materials, then, are not fixed attributes of matter but are processual and relational. To describe these properties means telling their stories [12] (p. 1).—Tim Ingold

In this article, we consider the “thingification” of disability as useful, considering its (un)making as it interacts with beads among women in a specific place.

Here we do not just follow a representationalist approach which would imply that we have to “read beads” to uncover their meaning. We follow a postrepresentational approach in which materials participate on an ontological level, as part of a becoming. What do beads do? What do they re-create? What e/affects do they have? We want to examine how beads become part of an ongoing process of disability and world formation. By doing so, our research also enters a more recent idea about disability as containing a dimension of potentiality. Devlieger [15] describes this rather contradictory approach to disability as follows: “Disabled people represent a market, people who work and contribute to society, and ultimately they are people, expressed in people-first language. Ironically, the term disability also expresses the opposite, the negation of ability” [15] (p. 348).

This contradiction is also part of our current research. Previous research in this direction includes Devlieger’s and Strickfaden’s work on disability, (non-)place, and the senses. In the three related articles [16,17,18] they describe, amongst other things, the potential of disability. Their article about the Brussels Metro shows how disability can transform a non-place into a different space based on the sensorial influence that arose from developing systems of navigation from a visual-impairment perspective. Their work exemplifies the idea of disability as generative for cultural production.

In the course of this article we will consider the relationship between disability, gender, and beads in Kinshasa, DR Congo, by mainly focusing on one part of the storyline, namely beadwork. In the next section we outline our methodology. The third section explores beads as a central element in our material approach to disability. Beads can generate many stories, and we selected one snapshot out of the story of beads in relation to disability in the context of one particular place, namely CEPROMEFHA in Kinshasa. This ethnographic account unfolds in the fourth part of our article, where we offer a fragment of the meshwork of beads and people. In the fifth part of this article, we shall discuss this meshwork more in depth, and explore beadwork as a site of meaning-making and self-making (i.e., as enmeshed in social relations and part of disability, gender, and world formation).

2. Materials and Methods: “Joining in Correspondence”

The data presented in this article are the result of a number of field trips in Kinshasa’s urban environment organized by the first author during five visits to DR Congo between 2010 and 2015. Fieldwork was carried out in the context of the first and second author’s doctoral studies and its supervision by the third author. Participant observation took place in the context of the three authors’ previous and current research about the socio-cultural worlds of Congolese people with disabilities. These separate research projects also include a focus on material culture. Participant observation means here “to join in correspondence with those with whom we learn or among whom we study, in a movement that goes forward rather than back in time” [19] (p. 390). In other words, the authors participated to various extents in participants’ activities; one of these activities was beadwork at CEPROMEFHA. To learn about the material composition of the inhabited world of people with a disability in Kinshasa, Ingold suggests we should engage ourselves “quite directly with the stuff we want to understand” [14] (p. 3), namely by inscribing ourselves in the process of beadwork. Experience thus becomes an entry point in doing research at the center. As such, the material in this article is first of all the outcome of an anthropological enquiry as a practice of correspondence or “attentiveness” [12] or participant observation, and not merely an attempt at representation. This also implies that the knowledge production is contextual, and moreover, it is the result of the authors’ collaboration with participants. During and after participant observation, the authors made (thick) descriptions and followed an interpretive approach. During and after these visits to the center, the first two authors organized interviews to complement findings from the participant observations and to write up their ethnography. Our study engages with anthropology, pedagogy, disability studies, and gender studies.

3. Beads as Things in the Making

Beads and bead products are a particular aspect of Kinshasa’s evolving material culture. There has been a long tradition of anthropological interest in material culture, in general, and in objects, goods, and, more specifically, materials. Research about material culture and disability mostly focuses on the (accessibility of the) built environment, or on the multiple aspects of medical objects, or assistive technology. Our research corresponds more with the literature on artefacts that are the result of a specific training in job skills for people with disabilities [20]. The objects that we consider here have become part of the every-day lives of a number of people with disabilities in Kinshasa, DR Congo. The material aspects of disability have especially been, until now, examined in a European and a North-American context. Thus, the present article intends to expand this research to an African context.

In general, beads have a very long history and have experienced a worldwide diffusion [21]. Although first perceived as trivial, nowadays there is a growing body of research and literature about them. Beads have long since become items in museum collections and have been part of several ethnographic descriptions of objects that are made from them. In many cultures, beads have great significance. Much has been written about beads in Africa, specifically (e.g., Nigeria, Cameroon, and Kenya), and about the mass import of trade beads from Europe [22], as well as about bead production and beadwork in several African countries [23,24,25]. In the context of DR Congo (formerly known as Zaire), beads are often discussed in archeological [26] or historical research [27,28] as part of a monetary system, or arts and crafts, and often for decorative or ritual purposes. Margret Carey [25], for example, mentions “beaded clothing and masks found among the Kuba of Zaire, and the beaded crowns worn by royalty of the Pende and Yaka of Zaire” (p. 88). Although beads were often made out of natural materials (e.g., seeds, shells, wood, terracotta, glass, and copper), today plastic beads are common in markets and are used in the production processes of certain commodities. The introduction of new materials, such as plastic in crafts work and in particular socio-cultural contexts (e.g., the household, community rituals), has also been a recurrent topic in research [29,30,31]. The plastic beads that are discussed in this article are not produced in Congo but in factories elsewhere. A discussion of how plastic beads came into existence is beyond this article. Rather, we will focus on beadwork and examine its particular context in relation to people with disabilities, and more precisely on women with physical disabilities as makers of products from plastic beads in CEPROMEFHA in metropolis Kinshasa. The beads (“perles” in French) have an average of 5 mm-diameter in their circular form and most are the same size. They have a very low weight and are available in various bright colors. The beads are mass produced plastic items that are smooth and have a hole in the center. In CEPROMEFHA, people with disabilities thread beads with fishing line to make various products such as key rings (Figure 1), neckties, coasters (Figure 2), handbags (Figure 3), mobile phone covers, curtains, table cloths, and banners (Figure 4). These commodities show various designs but similar patterns often return. These patterns, for example, show the Congolese (Democratic Republic of the Congo and Republic of the Congo), French, or Belgian flags. Images of African animals, as well as colorful geometrical figures, such as lines, squares, rectangles, pentagons, and star and diamond shaped forms, are common. The national colors (blue, yellow, and red) reoccur in various objects. A number of items include phrases or words referring to particular celebrations (e.g., 50th Anniversary of independence) but also people or institutions (e.g., decorations for a doctor’s office or a church). Lots of houses are decorated with objects made of beads that symbolize the history and the culture of DRC, its resources, its animals and plants, and its suffering (especially during the period of colonization). Throughout its history, the country had several flags, and these different flags are reproduced in beadwork. Particular items such as musical instruments (e.g., a tam tam), tools (e.g., fishing nets and pottery) are also portrayed.

Figure 1.

Key rings.

Figure 2.

Coasters.

Figure 3.

Handbags.

Figure 4.

Decoration for a doctor’s office.

Bead products manufactured by people with a disability are a rather new phenomenon in the city. A number of interlocutors mentioned that, due to the massive arrival of West Africans, bead products and plastic beads entered Kinshasa’s urbanscape. Kinois (i.e., inhabitants of Kinshasa) call these West-African salesmen “ndingaris”. These salesmen buy their products in countries such as Senegal, Niger, Mali, Ghana, and Nigeria and bring them to DR Congo to resell them. At the same time, they often married Congolese women. Concurrently, negotiation took place, and disabled women started to acquire beads instead of finished products. They also worked through the wives of the ndingaris rather than the ndingaris themselves. The Senegalese have an especially long history of producing products made of beads, as well as embellishments with beads. The Senegalese equally have an extensive history of buying beads in large quantities, especially from China, and in some cases from Brazil. Also, people from Chad, Burkina Faso, and Mali have a long tradition of wearing clothes embellished with beads. The ndingaris who come to sell in Kinshasa are rather smaller businessmen. The products became very expensive, so Kinois started to make them by themselves. Women with disabilities were notably among the first to buy beads, as they were already into artisanal work. They have risked by trial and error not only to buy the beads and make the products, but also to be innovative in making new products and new models. The Catholic Church has been instrumental in creating a culture in which women with disabilities are involved in artisanal work, partly driven by the idea that they could not be involved in hard work, but rather could be involved in lighter work. However, women with disabilities might also have taken initiative to claim this particular market, and able-bodied women may also have rejected entering into this market for reasons of being associated with them.

4. Beads and Disability: A Story

The Centre de Promotion Maman Efinole des Femmes Handicapées (CEPROMEFHA) is located in the midst of the Kasa-Vubu commune. In Kinshasa’s vast cityscape, the multiple centers for people with disabilities are often out of sight of the ignorant passers-by. In many instances, these social enclaves find shelter in someone’s home or in buildings that lost their previous function due to the pillages in the 1990s. Many of these sites belong to the Church or the State and are, for the time being, assigned to an association or being occupied by a group of people, sometimes called a “floating population” (“population flottante”).

A small dirt road with the potential of turning into a mud pool during the rainy season brings one from the avenue to a robust metal gate. Upon entering the enclosed courtyard of the center after 9 am, the sound of mostly women’s talking comes towards its visitors while the noise of the busy main road vanishes into the background. The center consists of a courtyard and a number of small buildings surrounding it. There are several sheds that offer protection against the sun or the rain. Groups of women mostly gather under these sheds around large tables and in colorful plastic chairs. In 2015, one of the sheds fell down, so the entire group of women moved to the other side of the courtyard to gather beneath the other shed. Men and women who are part of the organization of the center come together inside a small building on the right side of the courtyard. Another small building is located opposite the entrance. In this building, men, in particular, deal with administrative tasks. Life in the center is never completely blocked off from life on the street as children’s neglect of borders regularly opens up the place, as do many other wayfarers (e.g., customers; sellers of jewelry, food and other items; journalists; researchers). Several balconies of the multi-story building next to the place are overlapping its courtyard. Its inhabitants, their daily occupations, and clothes lines are often merging in one way or another with life in the center.

The central space in the courtyard is marked by the presence of several tables put next to each other to form one big table. This is a highly gendered space, as most of the time the area around or near this table is crowded with women, and men are rather unwelcome. In the corner of the courtyard next to the small building on the right side there is a separate space with a blackboard against the wall. In this part of the center letters and words appear on the board and float through the air. Next to literacy courses, a number of other activities are organized for women and also for men with disabilities. Besides literacy, the women also learn basic trades such as tailoring or handicraft production. Most of the action seems to be centered around one specific activity that draws a lot of attention. The big table is replete with singular colorful beads lying around or collected inside small plastic bags (Figure 5), and in between are beads as thing-manifested materials. Very few women are seated in a tricycle or a wheelchair. Above all, it is the presence of various kinds of crutches leaning against a table or a wall that discloses this place on the inside as a center for people with disabilities.

Figure 5.

Plastic bag with beads.

Much of the activity around the big table is focused on threading beads with fishing line. As such, the women’s hands creatively indulge in the endless possibilities presented by the small and mass-produced plastic material. Only a limited number of materials are necessary to produce various objects such as handbags (some with a plastic bag (to guard against the rain) and cloth on the inside, some without), mobile phone bags, pads, key chains, tablecloths, and much more. All the items have very bright, striking colors. Aesthetic quality comes from the different (but often repeated) designs. Most of the products have a feminine sense about them (their round shapes?) but, strangely enough, also an ambiguous feeling of both cheerfulness (the colors?) and sadness (the cheapness?). The most important material for these objects, namely the small plastic beads, looks and feels like cheap plastic. The final products are rather strong and flexible at the same time. For some visitors they might seem like simulacra of particular objects that often appear in industrialized chains of mass production. In a sense, these products mirror on a micro-level the city itself that “exists as a heterogeneous conglomeration of truncated urban forms, fragments and reminders of material and mental urban ‘elsewheres’” [32] (pp. 233–234). For some visitors, the place might evoke the image of a sheltered workshop.

Overall, men’s involvement in this production process is very uncommon. At this stage of the chain, the beads activity is mostly a women’s enterprise. After one of the women (often the same one) comes back from the market where she bought a particular weight of beads, the small plastic bags enter the central setting and end up on one of the tables. A number of women weave the beads into different designs and finished products while sitting together (Figure 6 and Figure 7). There are no templates nicely drawn on paper for these women to copy. Women teach the process of making these items to newcomers in a very straightforward way. Newcomers (new members or curious researchers) receive person-to-person training from one of the more experienced women. It seems that the production process of each item follows the same pattern. One starts with the form of a square that comes into existence by threading four beads to each other with the fishing line. The square eventually turns into a bigger shape (e.g., a simple coaster) that can be connected to other shapes, thus becoming different products.

Figure 6.

Threading beads.

Figure 7.

Threading beads.

While one woman takes up a role as teacher, the other instantly becomes her apprentice. Education first consists of imitation by watching attentively how the teacher’s fingers move, and by meticulously following all the steps. During beadwork, bodies take on different postures as both newcomers and experienced members un/consciously adjust their bodies (eyes, fingers, back, head, shoulders, legs, and even feet) to the situation of making [33]. There is always the chance of pricking one’s fingers with the needle when concentration is lost during this dance of materials. After the more precise act of pulling the thread through a tiny needle eye and ragging the thread through the first beads, one could easily lose one’s self in the repetitive manufacturing of the simple basic shapes. Even a beginner very soon becomes totally submerged in the same process as all the other women around the table where “the mindful or attentive bodily movements of the practitioner, on the one hand, and the flows and resistances of the material, on the other, respond to one another in counterpoint” [33] (p. 101).

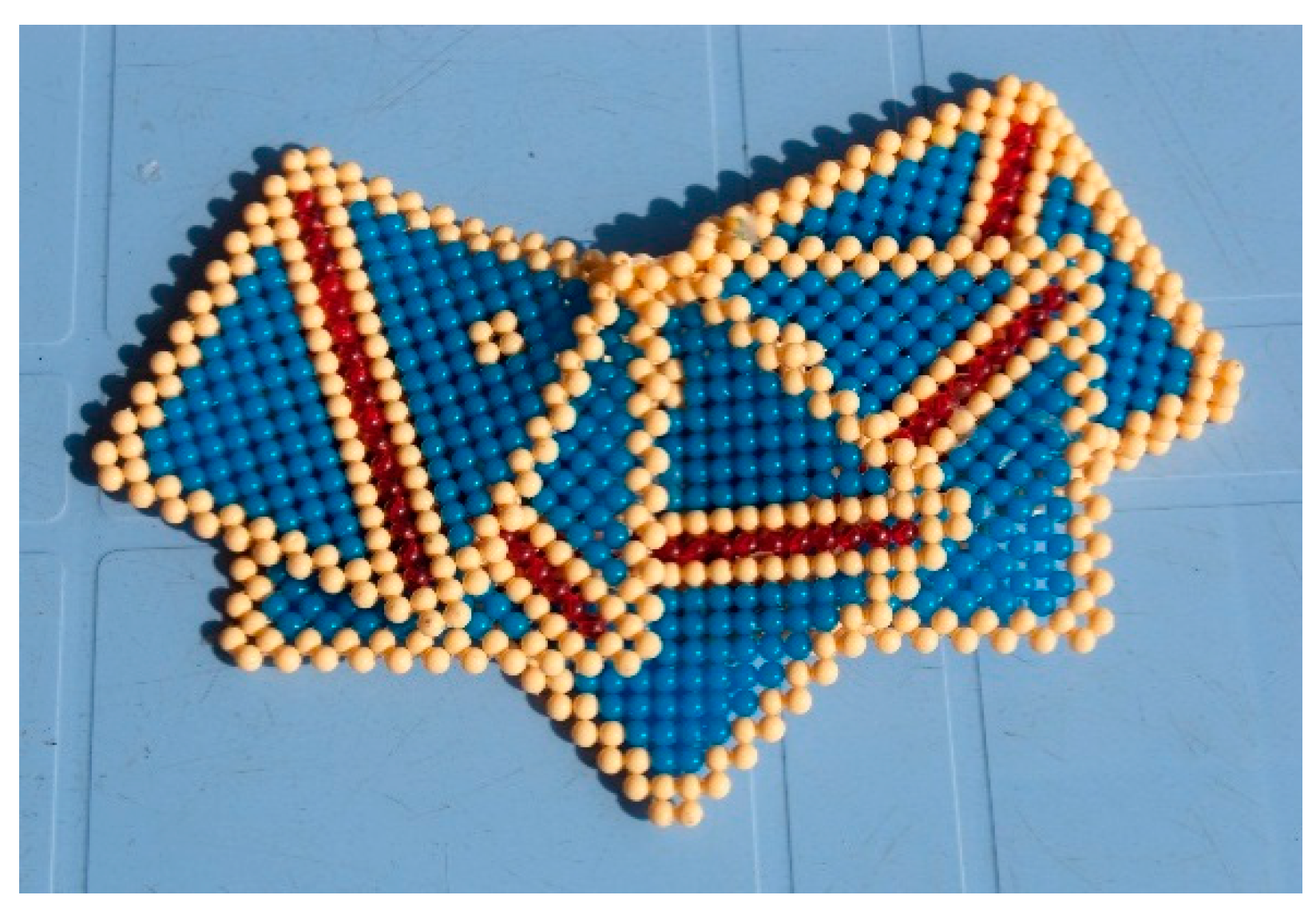

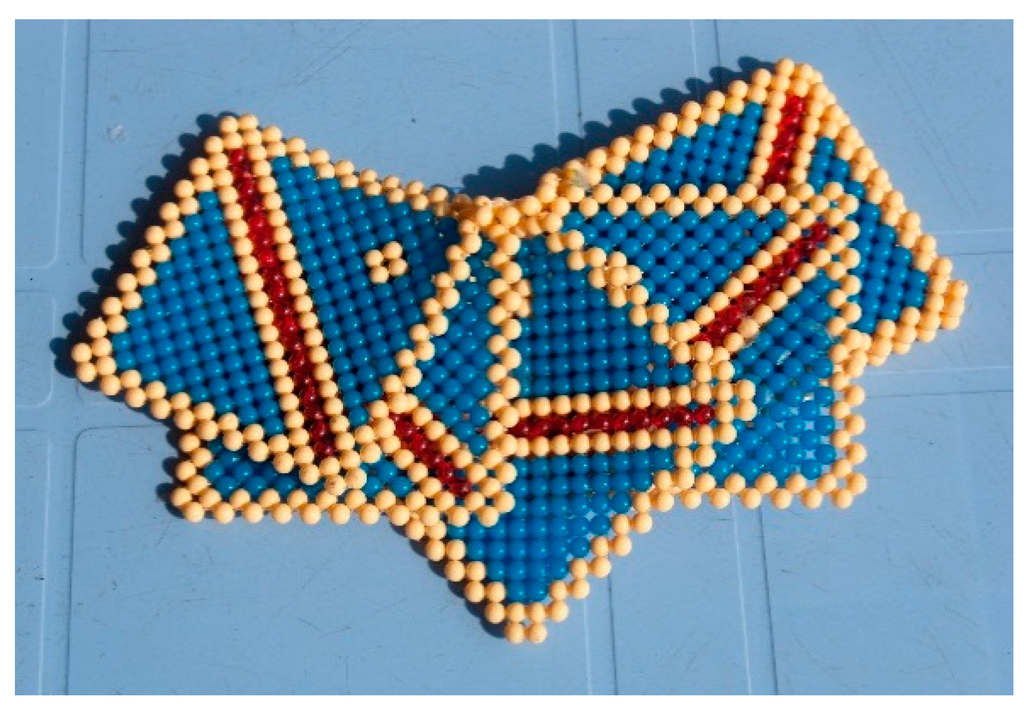

After a beginner understands the necessary basic skills to handle the material, the focus is moved from the teacher to the other events in the courtyard, and especially around the big table. More experienced members are able to continue conversation and laughter without the need to constantly look at the handled materials. Most of the time their hands take over from their eyes as their fingers count the number of beads, thus following the pattern in their mind. However, even a beginner with less fine-tuned skills who has to interrupt conversation from time to time to ask for help will soon find herself in the flow of things. While weaving fishing line through beads, one also finds oneself to some extent capable of ragging different conversations together and weaving one’s self into the fabric of the group. Most beginners will find it an easy rite of passage. The work happens in a relaxed way, as there is no stress to reach a certain quota. Sales do not seem important or successful enough to increase the production process. Orders are finished without much upheaval. Thus, the numerous hands incorporate beads into lines and shapes and small forms into bigger pieces. The quality of the weaving together of different materials (and a number of unwanted knots in the fishing line) remains as a trace of one’s presence. During some visits we found large cloths made out of thousands of beads lying on the floor, the result of many hours and hands’ work. These products would present a flag or other symbols (e.g., Figure 8) depending on who ordered them. On special occasions, such as “la journée de la femme” (Woman’s Day), final products like these are presented to a wider public and become a visible symbol of these women’s knowhow, skills, and group effort.

Figure 8.

Nappe (cloth).

The emphasis is, however, not always on the products themselves but on being there together, and on processes of transformation. In interviews some of these women stated that they go through a lot of physical effort and spend much money to come to the center by public transport from the other side of town. The little bit of money that these members indirectly receive from the government for being present in the center is not enough to cover even their transport costs. Participant observation and interviews made us understand that by sitting together around these tables, and sharing their work, that these women also share their troubles and life stories. Women often give advice to one another or discuss their daily concerns. Multiple moral landscapes unfold during this time of threading and weaving. Various different backgrounds (age, disability, ethnicity, marital status, and so on) are all presented, but not very important to have membership. Humor is part and parcel of life at the center, as laughter often arises from one of the different groups. Next to a sense of belonging, a feeling of equality is also created, as women with disabilities often make fun of each other’s shortcomings, but members without a disability are never allowed to do so. Unusual visitors such as the researchers are from time to time reminded of their outsider role by little jokes and remarks. These remarks would hint at being “different”. During participant observation, the male researcher, for instance, was laughed at for doing a woman’s job. The first author who is a female Belgian visitor had to figure out the seriousness of jokes about witchcraft. Other jokes involve searching for impairments with women who at first sight do not have any. After jokes like these, one notices that not all women around the table have both hands and arms. With all the movements that are going on around the table the particular movement of hands sometimes becomes less important. The various skills that one learns at the center are an obvious reason to be there, but everyone first of all emphasizes the members’ solidarity and the feeling of communitas that they share. Most narratives collected during participant observation at the center defined fellow members as family.

“This is my family! I love these women more than my proper family”.(Mama Efinole, interview in Belgium, November 2015)

Between 14:00 and 15:00 a good number of bead products are on the table, and most hands have stopped working. Some women are just sitting there, not making anything, sometimes even looking bored. Products are not really handled with care but sometimes just thrown to the “teacher” and put into a plastic bag at the end of the day. Some products end up on a pile; others fall on the dusty ground. Beginner’s work is evaluated and approved of. Unfinished work is taken up the next time. The weaving of the beads has stopped and the woven social fabric is temporarily broken up when all wayfarers leave the center to go their separate ways.

One evening, while sitting on a terrace somewhere in Kinshasa, two women passed our table, one of them carrying a sewing machine. One of us wanted to know whether the youngest of the two, who had a physical impairment, was familiar with making products from plastic beads. Soon, she reappeared at our table as a salesperson with a huge bag, putting a number of well-known and surprisingly new items in front of us. She did not go to a center and had learned the craft from her mother, who in her turn had learned it in a church center. In this context, the researcher—previously an apprentice—metamorphosed into an opportunity, namely a possible customer.

Weaving these threads and beads into colorful products also becomes the threading and weaving together of different people, transmitting skills, and connecting stories, thus linking one person to another throughout space and time, in one long unfolding and meshing of lines.

5. Discussion

5.1. Contextualizing Disabilty in Kinshasa

In 1988, Mama Efinole Madeleine Yelika founded the center for adults with disabilities that carries her name. She often mentions how lucky she was to have parents that were able to take care (“prise en charge”) of their child with a disability. Aware of this advantage, she started up CEPROMEFHA together with some other women and became the center’s president with the aim of promoting women with disabilities. Although a number of men do engage in the center’s daily activities, in general, men with a disability are thought of as being too agitated or not patient enough to participate in this environment. Several people at the center, including Mama Efinole, mentioned that their impairment was the result of polio at a young age. Other women’s impairments were caused by traffic accidents, or the war in eastern Congo.

In this center, adult women receive an education and are trained in particular activities that could offer them an income. Like in many other centers, these activities encompass (amongst others) dressmaking, hairstyling, and making all kinds of products out of different materials. As such, women with disabilities can become economically self-sufficient. This in turn can enable them to take care of their families. In 2011, the embassy of the United States in DR Congo recognized the center for its work as they offered Mama Efinole their “Woman of Courage” Award during a ceremony in Kinshasa’s Grand Hotel. To explain this achievement, we will give an outline of the context in which CEPROMEFHA and the lives of most of the adult women in the center are to be situated.

Ngoma-Binda [34] argues that each disability is a social phenomenon that demands solidarity. In a Congolese context, this necessity for solidarity originates from a particular human-world view in traditional society. “The world is understood as wholly, as an internal coherent unity, in which each person or each being has his responsibilities towards the others” [34] (p. 24). However, Kinshasa’s modern and capitalist reality puts former clan and family solidarity to the test [35,36]. Moreover, disability itself has become especially individualistic and demands new and specific structures and strategies for social integration. Following Zamenga Batukezanga [37], Ngoma-Binda [34] mentions that charity cannot be a solution. Society needs to give people with disabilities the possibility to take care of themselves. Consequently, disability appears as a very paradoxical phenomenon within Kinshasa’s modern environment that includes occupations such as beggar, parasite, modern hero, and “bricoleur” [38].

In general, disability in Kinshasa needs to be analyzed within a highly complex context of globalization, capitalism, the postcolonial nation-state, and the multiple realities of African urbanization. Interestingly, the way disability is enmeshed in Kinshasa’s urban environment gives rise to a number of peculiar phenomena. One example, on a technological level, is that of the tricycle as a kind of “assemblage”. The tricycles’ particular shapes in Kinshasa’s city landscape are not only the result of mobility needs in the city, but also take form according to the social and economic circumstances [39] created by globalization. The activity of beadwork also needs to be understood as such a phenomenon.

Political instability (due to, among other reasons, lootings and wars in the 1990s) is ongoing and has its consequences on the socio-economic level of society. The State apparatus brings forth new disability phenomena, and the State is unable to develop sufficient structural solutions to improve people with disabilities’ everyday lives. At the same time, there are particular processes that instigate the social organization of different groups of people. In “Reinventing Order in the Congo” Trefon, for instance, refers to the “inventiveness of people’s practices and mental constructions” as a response to a failed Congolese State [40] (p. 3). As an example he gives the ONGization of society. “Although the NGO phenomenon is seen as being foreign and imported, Kinois increasingly speak of NGOization as a new form of social organization” [41] (pp. 100–101). Responsibility for people with a disability (“le prise en charge”) is “in the hands of humanitarian organizations. The approach based on actual needs is stronger than the rights approach” [42] (p. 95). In that sense, most structures that support people with disabilities in Kinshasa are, in fact, philanthropical [38]. Churches’, Non-governmental organizations’ (NGO’s), and various associations’ work is complemented with initiatives from commercial companies (e.g., Vodacom telecommunications) or foreign political institutions (e.g., Embassies). The number of organizations for people with disabilities is enormous, and many among these have even become transnational. For now, all these different structures manage the huge amount of people with disabilities in the capital, estimated at 120,000 people. Therefore, these social support systems carry a heavy weight.

At the same time, people with disabilities have trouble getting involved in society through family, education, employment, or even participation in the city’s public space (e.g., when assistive technology is necessary, but not available or affordable). Most people with disabilities work in the second economy, or in niches within the second economy, known as “petit métiers” or small jobs [43,44]. The involvement of people with disabilities in border trade at some of the country’s frontiers is well established. For decennia, the frontier between Kinshasa and neighboring capital Brazzaville has been a hot spot for people with disabilities [43,44,45,46,47,48,49]. During a visit at a doctor’s practice, the doctor explained to us how people with disabilities involved in this trade suffered from severe health conditions, and even physical malformation, due to the carrying around of heavy weights. Thus, the reality of disability entangled with poverty in Kinshasa’s contemporary urban environment also reveals the problematic making of physical bodies.

In Kinshasa, many people with disabilities are neglected by their family and rejected by their family-in-law. Many of them end up on the streets of Kinshasa, often without a proper education or employment. People with disabilities—especially women—often mention the problems they have to establish their own family. Although many among these women with disabilities have children, involving oneself in the social fabric through marriage is very difficult. Women with disabilities are often engaged as second wives (“deuxièmes bureaux”) and are regularly abandoned by their partners after being pregnant. Consequently, women with disabilities are one of the most vulnerable groups of inhabitants of Kinshasa.

People with disabilities in Kinshasa have developed their own networks to participate in society. These networks originate from, for instance, economic and other activities and not just from clan or family relations. Centers form an important knot for some of these networks to exist. As Mvuezolo and Kinkani indicate “these centers offer programmes for medical support, education, readaptation, professional apprenticeship, employment, housing and transport that help people with a disability” [50] (p. 46).

5.2. Un/Making Gender and Disability

Disability and gender are part of a process of “making”, as not only being produced, but also as producing, through the practice of beadwork. At the same time, we want to emphasize the blurred boundaries between the local and the global, the individual and the collective, and the self and the material. The material approach in our text considers beads as artefacts. In what follows we show how notions of place, space, practices, and artefacts construct gender and disability identities.

We start our discussion at the place where a particular group of people with a disability meet, namely the center, being a specific historical and socio-cultural place where women receive an informal education. We can, however, also think about the center as a “localized space” [51] (p. 25). The center as a place is not isolated, but opens up through all kinds of flows of multiple relations (through people and materials) that connect the “inside” and the “outside”. The center is never a static place, but a space where several processes are ongoing. These dynamic movements happen on a physical level (e.g., women leave the center to go to the market and bring back beads inside the center; they gain knowledge about the market) and on an imaginary level (e.g., they make a special bead product for Women’s Day; aspirations, etc.). These movements relate to individuals (e.g., Mama Efinole) but also to a collective of people (e.g., the staff at the center, the entire group of people with a disability at the center, the women who are doing beadwork). Place relates to space through these relations between people, but also through the material. When beads enter the center, they have an impact on its environment. Thus, not only the people, but also the artefacts shape the center as a place/space. For one thing, some of the activities have changed. Materials and space are co-produced (in processes of creation and use). During beadwork as an activity, relationships between people and materials come to the forefront.

Cole [52] states that people and environments mediate culture by interaction through artefacts. The everyday activities at the center are amongst others mediated by beads as artefacts [52] and are historically situated. As mentioned before, women with disabilities were already especially familiar with various crafts. Most of these women belong to lower social strata and are not always able to come to the center (e.g., due to the weather conditions or a lack of money to pay their transport). Work with beads is affordable and allows home-based work, but also both individual and group efforts. When the organizers of the center decided to start with beadwork they took into account the life conditions of the center’s members. These conditions and the center’s environment are in correspondence. In and out the center, the skills are specifically passed down from woman to woman. According to the center’s president and vice president, religious sisters taught the first skills at the center.

“We came to learn and afterwards others came to learn from us”.(Vice-President Ingrid in an interview, September 2015)

At the center, we observed that mostly women seated around the table are engaged in beadwork. Stringing and threading beads together is especially a female labor. One could even say it is their specialization. The men who participate in the center are more occupied with administrative tasks. Outside the center, men with disabilities can be perceived as doing more masculine work (e.g., being a musician or doing work that is physically more challenging). Moreover, gender at the center is also co-constructed through various salesmen who bring jewelry or cooking pots to the center, and through other interactive practices, such as women styling each other’s hair or using make up.

The group of women with disabilities involved in beadwork is not very homogenous. They do share adulthood and a poor educational background. According to Mama Efinole, the women at her center have various age and ethnic backgrounds. Some of them are married, but most of them are not. Many among them have children. There are women who witnessed war in the eastern part of the country, and women who suffered from disease, or were involved in accidents. The types of physical disability present at the center are very heterogeneous. Some of these women lack arms and hands to physically engage in beadwork, yet they participate in the collective effort.

On the one hand, beadwork as an activity and its products change women’s self-perception. Carey [25] notices something similar in her overview of gender and beadwork in Africa. During interviews, for instance, some women were delighted and proud to show new designs.

“I create models. I create! So, they gave me training, but now I am creating models myself. I create, I innovate, I make things that we did not learn during training”.(Interview with Mama Therese, at her house, September 2015)

These women often define themselves by what they are doing, by their beadwork, by what they create, or what they are aspiring to through their informal education at the center. Activities at the center, such as beadwork, also give them a sense of worth in a city where they are often made to be worthless. Through beadwork, they show their ability to produce things, but also their ability to engage with society. This engagement does not only take place on a socio-economic level (i.e., producing and selling things), but also on a symbolic level. The artefacts can carry symbolic meaning too, as several of the “nappes” (cloths) can reflect religious or political events. During Women’s Day, for example, the women dress up in similar “pagnes” (traditional female clothing) and participate as a group in parades while showing their work.

“I am really good at making art with beads. We sell these items to politicians (ministers, national deputies), expats, and other visitors from abroad. Especially the latter are potential clients. To attract their attention we prefer to include images, colours and writings that symbolize something. For example, sometimes we receive an order from married couples in which we include the phrase: ‘nous nous sommes mariés pour ne pas divorcer’ (we are married for life). We put the name of the husband on the left and his wife’s name on the right, to indicate that they love and accept each other. It shows that they share the same heart, thoughts and love. Our clients put these cloths against a wall in their living room or on the door of their bedroom. For them it is a kind of decoration but it is also a message to visitors about their intimacy”.(Interview with Bibiche at the center, August 2015)

However, beadwork as an activity does not just function as an informal education that provides these women with a kind of self-esteem and independence. The women at the center showed pride when they invented their own patterns (showing self-expression), but sometimes they also just seemed bored with the products. Moreover, product sales are not very high and are not their main motivation to come to the center.

The environment of the center stimulates different kinds of dynamic embodied interactions. While techniques of the body are being transferred from one person to another and produce colorful products, the women also engage on both a sensorial and a mental level. One could easily describe the atmosphere around the tables as sociable. The women create a sphere of belonging. In general, experiences are shared and there is a common understanding, thus bringing about integration in the group. Affective resonance ties the group together [53]. A number of women mentioned beadwork as positive for their psychological well-being.

“They reject you and most of the time they refer to you as a “sorcier” (witch). Your family writes you down as a witch. When you come to these networks… All of us are witches in these networks (laughs). When you leave your house they index you as a witch. You often go to these networks and the thoughts you had while at home… it decreases little by little and you find yourself only thinking about stories from these events and networks from work. These things remain in your mind instead of the thoughts you had while being at home”.(Interview with Mama Therese, at her house, September 2015)

“The idea of being here is first being together! The beads are a kind of work we created because we like to meet like that… Each person has her troubles. When you come you forget your problems a little bit because here there is moral chat, all kinds of chat, you are laughing, you forget your problems… Here, there is a little bit of ambiance and you forget everything you know”.(Interview with Ingrid, Vice-President of CEPROMEFHA, September 2015)

“It’s nice, you will see other people. A woman with a disability who arrives with her problems, stress. Arriving in such an environment where there is such a group of people that changes the idea. We also share experiences, certain stories”.(Interview with Mama Therese, at her house, September 2015)

Beadwork has an impact on the level of the individual and the group; the self and the artefact. Ingold [14] states that the properties of material emerge from processes in which human and non-human agents engage. The beads in the center have a smooth, round form with a hole in the center. This invites the threading of beads with other material, such as fishing line (which is also cheap and most importantly strong, flexible, and smooth) and a needle. The animacy of plastic beads is derived from its properties—from its “doing”. Beads invite particular motions such as threading. The vitality in the process comes from, for instance, the moving hands and the plastic beads, but not only that. In the making of products from plastic beads, different ingredients are caught up with each other (e.g., hands, eyes, air, the sun’s warmth, plastic beads, skin, feelings, energy, sound, fishing line, thoughts, the sharpness of the needle, and so on). These ingredients “circulate, mix with one another, solidify and dissolve in the formation of more or less enduring things” [12] (p.16). Not only beadwork skills are passed on.

“The younger girls are taught how to live in the family, how to be with others, how to participate in all that. They give these advices… they laugh very often… we have mamas who are specialized in things like that… What if you have a husband, how to take care of him, how to manage the household, prepare the table, how to receive guests…”.(Interview with Ingrid, Vice President of CEPROMEFHA, September 2015)

During beadwork, movements and transformations take place. From being an apprentice, a member transforms into a more experienced bead worker, and a teacher to others. One learns how to become autonomous and independent, while always with the possibility of support. Advice (moral, practical, and so on) is given. This could be about how to improve beadwork, but also about matters of personal life. During the performance of beadwork, differences—such as disability and gender, but also being Belgian or Congolese—are made, but also destabilized (through helping hands, but also through jokes). Stories about witchcraft and unfaithful husbands, but also alternative niche activities, enter the table discussions. What is taking place on a mental level is that mental processes are fundamentally transformed through artefacts. In their work, Cole and Wertsch [52] emphasize “the mediation of action through artefacts—in the development of mind”. Beadwork as a mediated cultural practice can transform the mental processes of the women at the center.

In the process of beadwork, these women share space and time, their stories, and their lives. During beadwork, boundaries are fluctuating. Perspectives and templates are shifting in these “centers of action”. One also witnesses a materialization of relationships. Each of these lines becomes like “one strand in a tissue of trails that together comprise the texture of the lifeworld… a relational field… not of interconnected points but of interwoven lines; not a network but a meshwork”[12] (pp. 69–70). Through a process of correspondence, or “inside learning” [19], a movement is taking place that is oriented towards future events. Moreover, during this ongoing apprenticeship and unfolding of stories, the world is unfolding too. Following Ingold, this momentary performance or movement is the basis for an ontogenesis. To explain this process, Ingold uses the word wayfaring, referring to “a trail along which life is lived” [12] (p. 69). When the center’s doors close and it is time to leave, all wayfarers go their own separate ways whilst continuing their “making” and their “differential becoming” [11]. As Ingold reminds us, just like walking, beadwork is more than a kinetic and kinesthetic practice. Ingold argues we can also talk about a creative force. A lot of “things” are “going on” during beadwork. Fisher [30] connects Ingold’s ideas about material relations and ecology with the concept of “plasticity”, and thus “materials are never ‘a material’, but a property or a set of potentials… and they afford metaphysical plasticity, which can be mixed with or fashioned into a sense of self” (pp. 126–127). The embeddedness of beads and the relations they create (e.g., in terms of skills of distinction, collaborative actions, and/or feelings of togetherness) is also expressed in McKay’s work [31] where identity is also described as having a kind of plasticity. Beads and people (materials on the move) allow themselves to be embedded into a web of connections in infinite ways, and beadwork becomes a site of self-making. In these processes, in and around the center disability and gender identity too become an act of creation, performed and future orientated.

In this final part we discussed how disability and gender are “made” in a very particular place in Kinshasa. It is important to notice that both gender and disability identities are not completely bounded to the center as a place. Some women with disabilities also meet each other outside the center to make bead products. The first author, for instance, met other women who did not belong to a center and who taught each other these skills. When we interpret the center in terms of space, relations between people and materials come to the forefront and show us how beads, as matter through the particular cultural practice of beadwork, co-produce gender and disability in Kinshasa. Beads as artefacts have the potential to make and transform disability and gender identities.

6. Conclusions

In this article we described how disability, gender, and materiality unfold in the context of an association of women with disabilities in Kinshasa, DR Congo. We did not want to offer a “reading” of disability as something stable or static. Here, we considered disability or gender or materials not as fixed entities, but as dynamic and relational. A focus on beads’ entanglement in people with disabilities’ everyday lives (here, life at the center during beadwork) gives us the opportunity to understand disability and gender identity from a material approach. A focus on materials should, however, always take into account a historical and socio-cultural situation. We did this by situating beads and disability within the particular context of Kinshasa where the center and beadwork are part of bigger networks.

Within the center we focused on a particular social practice, namely beadwork, as a meaningful behavior. The women in our research do not cross the city’s inaccessible, and sometimes even dangerous, environment only to receive professional knowledge and low government payment. In the temporary state of creating beadwork around the center’s tables, transformations take place. Women with disabilities find a sense of solidarity, equality, sociability, and most importantly, family at the center. Beads are becoming bead products. Disability and gender disappear and reappear throughout different social processes as affording a kind of plasticity.

As such, we have suggested that the “thingification” of disability is useful, considering its (un)making as it interacts with beads, among women in gender specific places, and across gender power differentials, while resulting in skills that become marketable. Through such relations, both social and material thingness is reached, in a manner that may be akin to sustainable development.

In these processes at the center, there is apprenticeship taking place and an unfolding of life. Moreover, we rather took this into consideration with the specific opportunities of how they could be brought together and interact, so that the plasticity of disability, gender, and beads results in particular connections that are local and specific, but not unrelated to the ways in which disability, gender, and materiality may interact in other places in the world.

While “things” are becoming, out of culture new “things” are emerging. This also means that this type of anthropological inquiry can never be completed, and is always ongoing. When talking about the world that continuously unfolds, as we are making it but inhabit it at the same time, we also need to give these processes our critical attention. A critical examination of phenomena wherein differences appear and disappear and become entangled can give us a different insight into the daily struggles of people with disabilities. This kind of critical approach is necessary in developing capitalist economies such as Kinshasa’s changing urban environment where disability is often connected to “worthlessness”. The women’s participation in the social fabric of the center is not determined by economic processes or value, as such, and thus creates particular types of social organization. However, outside the center, in Kinshasa’s vast landscape city life is unfolding too, creating new differences and moments of inclusion and exclusion.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the editor and the reviewers of Societies who provided us with critical comments and wonderful feedback, which allowed us to great extent to improve our article.

Author Contributions

Jori De Coster and Eric Metho Nkayilu are currently doing a PhD research about people with a physical disability. Both of them visited a number of centers in Kinshasa, DR Congo, in the course of their fieldwork. Based on a shared part of their fieldwork experience they decided to work on these particular data together. Jori De Coster put the data together in one document. Patrick Devlieger is supervising both projects and has organized a number of research projects on disability in Kinshasa in which both PhD students participated. Patrick Devlieger organized reading sessions about Tim Ingold’s work and Jori De Coster and Patrick Devlieger participated in Tim Ingold’s seminar in Leuven, which formed the basis of this work. Thus data were delivered and analyzed by Jori De Coster and Eric Metho Nkayilu. Patrick Devlieger supported and reviewed the document and added remarks for improvement.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Hall, S.; du Gay, P. Questions of Cultural Identity; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Castells, M. The Power of Identity, the Information Age: Economy, Society and Culture; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2004; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Barnartt, S. Introduction. In Disability as a Fluid State; Emerald Group Publishing: Bingley, UK, 2010; Volume 5, pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, J. Gender Trouble. In Feminism and the Subversion of Identity; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Devlieger, P. From self-help to charity in disability service: The Jairos Jiri association in Zimbabwe. Disabil. Soc. 1995, 10, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, J. Bodies That Matter: On the Discursive Limits of Sex; Routledge: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Grosz, E. Volatile Bodies: Towards a Corporeal Feminism; Routledge: London, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Grosz, E. Time Travels: Feminism, Nature, Power; Allen and Unwin: Crows Nest, Australia, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Gell, A. Art and Agency: An Anthropological Theory; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Deleuze, G.; Guattari, F. A Thousand Plateaus; Bloomsbury: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Barad, K. Posthumanist performativity: Toward an understanding of how matter comes to matter. Signs 2003, 28, 801–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingold, T. Being Alive: Essays on Movement, Knowledge and Description; Routledge: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Thrift, N. Non-Representational Theory: Space, Politics, Affect; Routledge: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ingold, T. Materials against materiality. Archaeol. Dialogues 2007, 14, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devlieger, P. From handicap to disability: Language use and cultural meaning in the United States. Disabil. Rehabil. 1999, 21, 346–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devlieger, P.; Strickfaden, M. Reversing the (im)material sense of a non-place: The impact of blindness on the Brussels metro. Space Cult. 2012, 15, 224–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strickfaden, M.; Devlieger, P. Empathy through accumulating techné: Designing an accessible metro. Des. J. 2011, 14, 207–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strickfaden, M.; Devlieger, P. The Brussels metro: Accessibility through co-creation. J. Vis. Impair. Blind. 2011, 14, 207–229. [Google Scholar]

- Ingold, T. That’s enough about ethnography! Hau J. Enthnogr. Theory 2014, 4, 383–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ott, K. Disability and Disability Studies. In Material Culture in America: Understanding Everyday Life, 1st ed.; Sheumaker, H., Wajda, S.T., Eds.; ABC-CLIO: Oxford, UK, 2008; pp. 152–156. [Google Scholar]

- Sciama, L.D.; Eicher, J.B. Beads and Bead Makers: Gender, Material Culture and Meaning, 2nd ed.; Berg Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Trivellato, F. Out of Women’s Hands: Notes on Venetian Glass Beads, Female Labour and International Trades. In Beads and Bead Makers: Gender, Material Culture and Meaning, 2nd ed.; Sciama, E., Ed.; Berg Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2001; pp. 47–83. [Google Scholar]

- Fagg, W. Yoruba Beadwork: Art of Nigeria; Lund Humphries: London, UK, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Carey, M. Beads and Beadwork in West and Central Africa; Shire: Aylesbury, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Carey, M. Gender in African Beadwork. In Beads and Bead Makers: Gender, Material Culture and Meaning, 2nd ed.; Berg Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2001; pp. 83–95. [Google Scholar]

- Clist, B.; Cranshof, E.; De Schryver, G.-M.; Herremans, D.; Karklins, K.; Matonda, I.; Polet, C.; Sengelov, A.; Steyaert, F.; Verhaeghe, C.; et al. The elusive archaeology of Kongo urbanism: The case of Kindoki, Mbanza Nsundi (Lower Congo, DRC). Afr. Archaeolo. Rev. 2015, 32, 369–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vansina, J. The Tio Kingdom of the Middle Congo, 1880–1892; Oxford University: Oxford, UK, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Atumisi Sinyange, A. La perle dans la société Lega (Territoire de Mwenga). Likundoli. Enquêtes d'Histoire Congolaise 2003, 21–32. (In French) [Google Scholar]

- Platte, E. Towards an African Modernity: Plastic Pots and Enamel Ware in Kanuri-Women’s Rooms (Northern Nigeria). Paideuma 2004, 50, 173–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, T. Fashioning Plastic. In The Social Life of Materials: Studies in Material and Society, 1st ed.; Drazin, A., Küchler, S., Eds.; Bloomsburry Publishing: London, UK, 2015; pp. 119–136. [Google Scholar]

- McKay, D.; Perez, P.; Bimuyag, R.; Bonnevie, R.S. Subversive Plasticity: Materials’ Histories and Cultural Categories in the Philippines. In The Social Life of Materials: Studies in Material and Society, 1st ed.; Drazin, A., Küchler, S., Eds.; Bloomsburry Publishing: London, UK, 2015; pp. 175–192. [Google Scholar]

- De Boeck, F.; Plissart, M.F. Kinshasa Tales of the Invisible City, 1st ed.; Ludion: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ingold, T. Making: Anthropology, Archaeology, Art and Architecture, 1st ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ngoma-Binda, H.-L. Vision africaine du handicap physique et progress de la société: Brève réflexion en compagnie de l’écrivain et humaniste Zamenga Batukezanga. In Handicap et Société Africaine: Culture et Pratiques, 1st ed.; Devlieger, P., Nieme, L., Eds.; L’Harmattan: Paris, France, 2011; pp. 19–28. (In French) [Google Scholar]

- Mudaba, Y.L. Kinshasa, Signes de Vie; L’Harmattan: Paris, France, 1999. (In French) [Google Scholar]

- De Herdt, T. Hidden Families, Single Mothers and Cibalabala: Economic Regress and Changing Household Composition in Kinshasa. In Reinventing Order in the Congo: How People Respond to State Failure in Kinshasa; Trefon, T., Ed.; Zed Books: London, UK, 2004; pp. 116–136. [Google Scholar]

- Batukezanga, Z. Homme Comme Toi; Association des Centres pour Handicapés en Afrique Centrale: Kinshasa, Zaire, 1979. (In French) [Google Scholar]

- Devlieger, P. Lecture de la société à travers certains phénomènes de handicap. In Handicap et Société Africaine: Culture et Pratiques, 1st ed.; Devlieger, P., Nieme, L., Eds.; L’Harmattan: Paris, France, 2011; pp. 29–39. (In French) [Google Scholar]

- Kohrman, M. Motorcycles for the Disabled: Mobility, Modernity and the Transformation of Experience in Urban China. Cult. Med. Psychiatr. 1999, 23, 133–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trefon, T. Introduction: Reinventing Order. In Reinventing Order in the Congo: How People Respond to State Failure in Kinshasa; Trefon, T., Ed.; Zed Books: London, UK, 2004; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Giovannoni, M.; Trefon, T.; Banga, J.K.; Mwema, C. Acting on Behalf (and in Spite) of the State: NGOs and Civil Society Associations in Kinshasa. In Reinventing Order in the Congo: How People Respond to State Failure in Kinshasa; Trefon, T., Ed.; Zed Books: London, UK, 2004; pp. 99–115. [Google Scholar]

- Lusambila, M. Encadrement, structures et experiences des personnes vivant avec un handicap en RDC. In Handicap et Société Africaine: Culture et Pratiques, 1st ed.; Devlieger, P., Nieme, L., Eds.; L’Harmattan: Paris, France, 2011; pp. 93–98. (In French) [Google Scholar]

- MacGaffey, J. Entrepreneurs and Parasites. In The Struggle for Indigenous Capitalism in Zaire; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- MacGaffey, J. Paradoxes, Problems and Opportunities in Zaïre. Am. Anthropol. 1997, 99, 369–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayimpam, S. Commerce et contrebande: Les réseaux d’importation des textiles imprimés entre Brazzaville et Kinshasa. Espac. Soc. 2013, 4, 63–77. (In French) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devlieger, P. Een Economische Niche in Congo. In Niet Normaal: Diversiteit in Kunst, Wetenschap en Samenleving, 1st ed.; NAi Publishers: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2009. (In Dutch) [Google Scholar]

- De Coster, J. Pulled towards the Border: Creating a Disability Identity at the Interstices of Society. Disabil. Stud. Q. 2012, 32, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yekoka, J.F. Les jeunes commerçantes handicaps moteurs dans la négotiation de la vie entre Brazzaville et Kinshasa (1970–2009). In Negotiating the Livelihoods of Children and Youth in Africa’s Urban Spaces; Bourdillon, M.F.C., Ed.; Africa Books Collective: Oxford, UK, 2012; pp. 105–122. (In French) [Google Scholar]

- Smith, S. Le Fleuve Congo; Actes Sud: Paris, France, 2003. (In French) [Google Scholar]

- Mvuezolo, I.; Kinkani, F.A. Handicap et développement: Un enjeu socio-économico-éthique. In Handicap et Société Africaine: Culture et Pratiques, 1st ed.; Devlieger, P., Nieme, L., Eds.; L’Harmattan: Paris, France, 2011. (In French) [Google Scholar]

- De Boeck, F. The rootedness of trees: Place as cultural and natural texture in rural southwest Congo. In Locality and Belonging; Lovell, N., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 1998; pp. 25–52. [Google Scholar]

- Cole, M.; Wertsch, J. Beyond the Individual-Social Antimony in Discussions of Piaget and Vygotsky. Hum. Dev. 1996, 39, 250–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mühlhoff, R. Affective Resonance and Social Interaction. Phenomenol. Cogn. Sci. 2014, 14, 1001–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons by Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).