The Development of a Self-Report Questionnaire on Coping with Cyberbullying: The Cyberbullying Coping Questionnaire

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Preliminary Study: Coping SRQs’ Literature Review

2.1. Materials and Methods

2.2. Results

| Scale | Used in, Total Items, N, Ages | TB/CB | Categorizations | α | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-Report Coping Measure (SRCM; [48]) | TB |

|

α’s ranged from 0.64–0.86. No adjustments were made α’s were (1) 0.71, (2) 0.77, (3) 0.61, (4) 0.64 and (5) 0.67 The stem of the SRQ was changed into “When I have a problem with another kid at school, I…”. Some items were removed because they loaded on multiple factors; α’s were (1) 0.75, (2) 0.72, (3) 0.70, (4) 0.57 and (5) 0.60 A modified version of the SRCM with 20 items (four per factor) was used. Participants were asked to apply the questionnaire to bullying situations The SRQ included a definition of traditional bullying. In addition to the usual factors, seeking support was split up into adults and peers, and the factors submission, nonchalance and escape were added The hypothetical situation was changed into “When in my classroom someone repeatedly bullies another classmate, I usually…”. Externalizing was not included. α’s were (1) 0.80, (2) 0.84, (3) 0.78, and (4) 0.68 In addition to items from the SRCM, items from the HICUPS [55] were used. Some items from the internalizing, externalizing and support seeking scale (SRCM) and avoidant scale (HICUPS) were used, preceded by “When bullied…” Items were judged on a 4-point LS. A modified 23 item version [56] was used A modified version of the SRCM in addition to scales from [57] (i.e., (6) conflict resolution, (7) revenge) were used. α’s were (1) 0.89, (2) 0.88/0.85, (3) 0.67/0.71, (4) 0.74/0.80, (5) 0.72/0.77, (6) 0.75/0.74, and (7) 0.82/0.88 | ||

| Adolescent Coping Scale (ACS) [46] | CB TB |

|

| ||

| Survey for Coping with Rejection Experiences (SCORE; [49]) | TB |

|

| ||

| Utrechtse Coping List—Adolescents (UCL-A; [47]) | CB | a.1 Problem focused (confronting, social support) | 0.59 | The questionnaire that measures coping with cyberbullying is an adapted version of the UCL-A, items were rewritten for coping with cyberbullying, and are judged on a 4-point LS | |

| a.2 Emotion focused (palliative, avoidance, optimistic, express emotions) | 0.85 | ||||

| b.1 Depressive/emotional expression | 0.91 | ||||

| b.2.Avoidance/palliative | 0.57 | ||||

| b.3 Social support seeking | 0.76 | ||||

| The Coping Strategy Indicator (CSI; [64]) | [65] (33 items, N = 375, age M = 15.98, SD = 1.41) | CB | 1. Problem solving | 0.85 | The questionnaire is based on previous measures (e.g., [1] and suggestions from students and colleagues. Items are judged on a 3-point LS |

| 2. Seeking social support | 0.87 | ||||

| 3. Avoidance | 0.69 | ||||

| Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire—Kids version(CERQ-k; [66]) | [67] (36 items, N = 131, age 9–11) | TB | 1. Refocus on planning | 0.75 | The study initially focused on anxious children. However, 61% of these experienced bullying. The CERQ-k is an adapted (i.e., simplified and shortened) version of the CERQ [68]. Participants had to judge items on a 5-point LS |

| 2. Rumination | 0.73 | ||||

| 3. Putting into perspective | 0.68 | ||||

| 4. Catastrophizing | 0.67 | ||||

| 5. Positive refocusing | 0.79 | ||||

| 6. Positive reappraisal | 0.67 | ||||

| 7. Acceptance | 0.62 | ||||

| 8. Self-blame | 0.79 | ||||

| 9. Other-blame | 0.79 | ||||

| Children’s Coping Strategies Checklist (CCSC; [69]) | [70] (45 items, N = 230, age 8–13) | TB | 1. Active | 0.84 | Participants had to judge items on a 4-point LS. The four broad coping categories consist of: (1) cognitive decision-making, direct problem solving, positive cognitive restructuring, seeking understanding; (2) cognitive avoidance, avoidant actions; (3) distracting actions, physical release of emotions; and (4) problem-focused support, emotion focused support |

| 2. Avoidant | 0.75 | ||||

| 3. Distraction | 0.63 | ||||

| 4. Support seeking | 0.89 | ||||

| German Coping Questionnaire for Children and Adolescents [71] | [72] (36 items, N = 409, age 10–16) | TB | 1. Emotion-focused | 0.69 | Participants had to judge items on a 5-point LS. The three main scales consisted of nine subscales: (1) minimization, distraction/recreation; (2) situation control, positive self-instructions, social support; and (3) passive avoidance, rumination, resignation, aggression |

| 2. Problem-focused | 0.85 | ||||

| 3. Maladaptive | 0.87 | ||||

| Coping Styles Questionnaire (CSQ; [73]) | [74] (48 items, N = 99, age 18–21) | TB | 1. Rational | 0.77 | The CSQ normally consists of 60 items. In this study, a 48-item version was used in which male participants had to judge items on a 4-point LS. This study focused on bullying in prisons |

| 2. Detached | 0.71 | ||||

| 3. Emotional | 0.85 | ||||

| 4. Avoidance | 0.75 | ||||

| Ways of Coping Checklist (WCCL; [75]) | [8] (35 items, N = 459, age 9–14) | TB | 1. Problem-focused | 0.82 | Participants had to judge item on a 4-point LS |

| 2. Seek social support | 0.77 | ||||

| 3. Wishful thinking | 0.73 | ||||

| 4. Avoidance | 0.28 | ||||

| Life Events and Coping Inventory (LECI; [76]) | [77] (52 items, N = 510, age 10–12) | TB | 1. Aggression | 0.81 | Participants had to judge items on a 4-point LS, specifically for which behaviors they used at school |

| 2. Distraction | 0.80 | ||||

| 3. Self-destruction | 0.77 | ||||

| 4. Stress-recognition | 0.75 | ||||

| 5. Endurance | 0.62 | ||||

| Coping Scale for Children—Short Form (CSC-SF; [61]) | c. [78] (16 items, N = 379, age 10–13) | TB | 1. Approach | 0.69 | Items had to be rated on a 3-point LS |

| 2. Avoidant | 0.70 | ||||

| The Problem-solving Style Inventory [79] | [80] (28 items, N = 236, age 12–15) | TB | 1. Helplessness | 0.80 | Higher scores mean more positive problem-solving style |

| 2. Control | 0.71 | ||||

| 3. Creativity | 0.75 | ||||

| 4. Confidence | 0.78 | ||||

| 5. Approach style | 0.73 | ||||

| 6. Avoidance style | 0.71 | ||||

| 7. Support-seeking | 0.73 | ||||

| Coping Orientation to Problem Experienced (COPE; [81]) | [82] (60 items, N = 1339, age 17–29) | TB | 1. Problem-focused | 0.92 | Participants judge items on a 4-point LS. Only the α for the complete questionnaire was mentioned |

| 2. Emotion-focused | |||||

| 3. Avoidant | |||||

| How I Cope Under Pressure Scale (HICUPS; [55]) | [51] (45 items, N = 311, age 10–13) | TB | 1. Active | 0.88 | Six items based on the avoidant actions subscale were used. Participants judged these items on a 5-point LS. Information about the scales, α’s and ages were found in [55] |

| 2. Distraction | - | ||||

| 3. Avoidance | 0.65 | ||||

| 4. Support Seeking | 0.86 | ||||

| Revised Ways of Coping (RWC; [83]) | [84] (66 items, N = 98, grade 6–12) | TB | 1. Problem-focused | The questionnaire measures styles used in relation to a distinguishable event. In this study, all participants were girls. They were asked to judge the items on a 4-point LS for relational aggression. α’s ranged from 0.59–0.88 | |

| 2. Wishful thinking | |||||

| 3. Detachment | |||||

| 4. Seeking social support | |||||

| 5. Focusing on the positive | |||||

| 6. Self-blame | |||||

| 7. Tension reduction | |||||

| 8. Keep to self | |||||

| ** | [85] (29 items, N = 573, age 12–13) | TB | 1. Counter aggression | 0.87 | Participants were asked to indicate on a 3-point LS how victims (including themselves) fit the situations. Two situations were dropped from the scale |

| 2. Helplessness | 0.75 | ||||

| 3. Nonchalance | 0.77 | ||||

| Children’s Emotional Dysregulation Questionnaire (CEDQ)* | [52] (9 items, N = 255, age 11–14) | TB | 1. Anger | 0.71 | Participants judge items on a 5-point LS. Higher scores reflect greater emotional dysregulation |

| 2. Sadness | 0.72 | ||||

| 3. Fear | 0.76 | ||||

| ** | [86] (9 items, N = 394, age M = 16.4, SD = 1.09) | TB | 1. Avoidance | 0.73 | This study focused on weight-based victimization. Participants were asked to judge 28 items on a 5-point LS. A subset of nine items was used |

| 2. Health behavior | 0.80 | ||||

| 3. Increased eating | 0.80 | ||||

| ** | [87] (10 items, N = 509, age 11–14) | TB | 1. Problem focused | 0.92 | Participants were asked to indicate how often each strategy (i.e., item) helped when being picked upon (based on [88]). α was only provided for the whole scale |

| 2. Seeking social support | |||||

| 3. Attending positive life events | |||||

| ** | [89] (14 items, N = 765, age M = 13.18, SD = 0.63) | CB | 1. Distant advice | 0.67 | Items were based on the results of a qualitative pilot study [90]. Students were asked what a hypothetical victim would do in a situation (situations varied between students) and had to rate the 14 items on a 4-point LS |

| 2. Assertiveness | 0.49 | ||||

| 3. Helplessness | 0.36 | ||||

| 4. Close support | 0.65 | ||||

| 5. Retaliation | - | ||||

| Items from LAPSuS project [91] | [92] (11 items, N = 1987, age 6–19) | CBTB | 1. Aggressive | Items were not specific for cyberbullying, participants were asked to rate the items on a 4-point LS with in mind being cyberbullied, physically or verbally bullied. The model had to be rejected (bad fits on RMSEA and Chi square test) | |

| 2. Helpless | |||||

| 3. Cognitive | |||||

| 4. Technical | |||||

| ** | [93] (26 items, N = 2092, age 12–18) | CB | 1. Technological coping | - | List of coping strategies was developed based on extensive literature review on coping strategies in general and coping strategies in cyberbullying. Classification was based on [94]. Participants indicated yes, no, or not applicable for each item |

| 2. Reframing | |||||

| 3. Ignoring | |||||

| 4. Dissociation | |||||

| 5. Cognitive avoidance | |||||

| 6. Behavioral avoidance | |||||

| 7. Seeking support | |||||

| 8. Confrontation | |||||

| 9. Retaliation | |||||

| ** | [95] (16 items, N = 830, age 8–14) | TB | - | - | Participants had to judge a list of 16 items on a 4-point LS (except for items related to making new friends). Items were based on coping responses validated in previous research |

| Questionnaire of Cyberbullying (QoCB)* | [38] (21 items, N = 269, age 12–19) | CB | - | - | A number of questions multiple-choice questions measured blocking the message or person, telling person to stop harassing, changing usernames, telling friends, telling parents, telling teachers, ignoring and not telling anyone |

| ** | [96] (11 items, N = 571, all ages) | CB | - | - | Participants had to indicate yes or no for each behavior |

| ** | [97] (4 items, N = 548, age < 25) | CB | - | - | The questionnaire included items on offline and online coping strategies. Participants were asked to indicate which strategy/strategies they had used, and how helpful these strategies were on a 3-point LS |

| TB | |||||

| ** | [98] (10 items, N = 219, age 18–40) | TB | - | - | Participants were asked to indicate which of 10 coping strategies they have used (e.g., I talked to the bullies, I tried to ignore it) in response to TB |

| ** | [7] (12 items, N = 1852, age 4–19) | TB | - | - | Participants had to indicate which of the 12 given strategies they have used in responding to TB |

| ** | [99] (3 items, N = 207, age 13–14) | TB | - | - | For each type of bullying (physical, verbal, social), participants first had to give an open answer about—And then had to choose a coping strategy from a list of eight to ten strategies and indicate how useful this strategy was |

| ** | [100] (1 items, N = 2308, age 10–14) | TB | - | - | Participants were asked “What did you usually do when you were bullied at school?” |

| ** | [101] (N = 348, age 9–11) | TB | - | - | The questionnaire was based on previous studies. Participants were asked to indicate on a checklist which coping behaviors they displayed |

| ** | [102] (N = 1835, age 11–14) | TB | - | - | Participants were asked to name all coping strategies they have used in response to TB. Later, these answers were coded independently by two authors |

| Internet Experiences Questionnaire (IEQ)* | [103] (N = 856, age 16–24) | CB | - | - | Participants could select as many options as applicable to adequately describe their behavioral reactions |

| ** | [104] (7 items, N = 323) | TB | - | - | Participants were asked to indicate on a 3-point LS what they would do in response to being hit, teased, or left out of activities. Four items were adapted from [105], the other items came from the literature |

3. Main Study: Developing and Testing the CCQ

3.1. Materials and Methods

3.1.1. Item Selection

3.1.2. Initial Scale Construction (Preliminary PCA to Reduce Number of Items)

| Item No. | Item Content |

|---|---|

| Item 1 | I wait for the cyberbullying to stop |

| Item 2 | I ask for help on a forum |

| Item 3 | I focus on solving the cyberbullying problem immediately |

| Item 4 | I vent my emotions to myself |

| Item 5 | I think that other people are experiencing things that are much worse |

| Item 6 | I tell the cyberbullies when their behavior is bothering me |

| Item 7 | I think the cyberbullying event will make me a “stronger” person |

| Item 8 | I retaliate by cyberbullying |

| Item 9 | I try not to think about the cyberbullying |

| Item 10 | I think that the cyberbullying is not hurting me personally |

| Item 11 | I try to find a new way to stop the cyberbullying |

| Item 12 | I express my feelings |

| Item 13 | I think that I cannot change anything about the cyberbullying event |

| Item 14 | I laugh about the cyberbully/event |

| Item 15 | I delete the message from my profile or e-mail |

| Item 16 | I constantly think how terrible the cyberbullying is |

| Item 17 | I let the cyberbullying happen without reacting |

| Item 18 | I try to find the cause of the cyberbullying |

| Item 19 | I act as if the cyberbullying did not happen |

| Item 20 | I throw or break stuff |

| Item 21 | I contact the people behind the website |

| Item 22 | I think that there are worse things in life |

| Item 23 | I think that the cyberbullying will stop |

| Item 24 | I talk about the cyberbullying event with friends, family or someone I trust |

| Item 25 | I weep with grief |

| Item 26 | I save print screens, messages and text messages as evidence |

| Item 27 | I think about fun things that are not related to cyberbullying |

| Item 28 | I ignore the cyberbullies |

| Item 29 | I ask someone (parent, teacher, friend, peer) for help |

| Item 30 | I cannot think about anything else than being cyberbullied |

| Item 31 | I tell the cyberbullies to stop |

| Item 32 | I joke about the cyberbullying event |

| Item 33 | I think that it is just a game with the computer or telephone |

| Item 34 | I think about which steps I need to take to stop the cyberbullying |

| Item 35 | I show my irritation to the cyberbully |

3.1.3. Participants

3.1.4. Analysis

3.2. Results

3.2.1. Principal Components Analysis

| Item | Pattern Coefficients | Structure Coefficients | Communalities | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mental Coping | Passive Coping | Social Coping | Confrontational Coping | Mental Coping | Passive Coping | Social Coping | Confrontational Coping | ||

| 9 | 0.729 | 0.248 | −0.057 | −0.148 | 0.711 | 0.343 | 0.138 | 0.043 | 0.589 |

| 3 | 0.695 | −0.025 | 0.160 | 0.051 | 0.748 | 0.102 | 0.355 | 0.270 | 0.588 |

| 11 | 0.660 | 0.034 | 0.083 | 0.263 | 0.712 | 0.132 | 0.157 | 0.422 | 0.572 |

| 18 | 0.619 | −.091 | 0.337 | −0.064 | 0.679 | 0.044 | 0.476 | 0.172 | 0.566 |

| 5 | 0.583 | 0.026 | 0.019 | 0.299 | 0.672 | 0.128 | 0.246 | 0.460 | 0.537 |

| 19 | 0.193 | 0.742 | −0.068 | −0.124 | 0.256 | 0.758 | 0.055 | −0.058 | 0.616 |

| 17 | −0.159 | 0.738 | 0.188 | −0.234 | −0.060 | 0.731 | 0.191 | −0.206 | 0.633 |

| 28 | −0.195 | 0.722 | -0.004 | 0.343 | 0.003 | 0.706 | 0.116 | 0.318 | 0.618 |

| 23 | 0.143 | 0.599 | -0.034 | 0.149 | 0.263 | 0.621 | 0.116 | 0.202 | 0.435 |

| 1 | 0.153 | 0.544 | 0.093 | −0.136 | 0.223 | 0.574 | 0.176 | −0.054 | 0.371 |

| 27 | 0.052 | 0.437 | 0.057 | 0.394 | 0.238 | 0.468 | 0.216 | 0.438 | 0.402 |

| 26 | −0.169 | 0.142 | 0.783 | 0.004 | 0.063 | 0.220 | 0.757 | 0.138 | 0.614 |

| 29 | 0.150 | 0.022 | 0.748 | 0.016 | 0.358 | 0.144 | 0.795 | 0.223 | 0.655 |

| 24 | 0.210 | −0.002 | 0.699 | 0.061 | 0.414 | 0.124 | 0.769 | 0.272 | 0.641 |

| 6 | 0.198 | −0.034 | −0.070 | 0.740 | 0.371 | 0.015 | 0.142 | 0.776 | 0.637 |

| 31 | −0.004 | 0.049 | 0.277 | 0.719 | 0.269 | 0.113 | 0.442 | 0.781 | 0.689 |

| 35 | 0.110 | −0.209 | 0.365 | 0.412 | 0.286 | −0.129 | 0.458 | 0.514 | 0.438 |

| Eigen values | 4.69 | 2.34 | 1.39 | 1.18 | |||||

| % of variance | 27.59 | 13.77 | 8.15 | 6.97 | |||||

| α | 0.77 | 0.73 | 0.73 | 0.68 | |||||

| Ω | 0.77 | 0.73 | 0.75 | 0.7 | |||||

| GLB | 0.77 | 0.79 | 0.76 | 0.73 | |||||

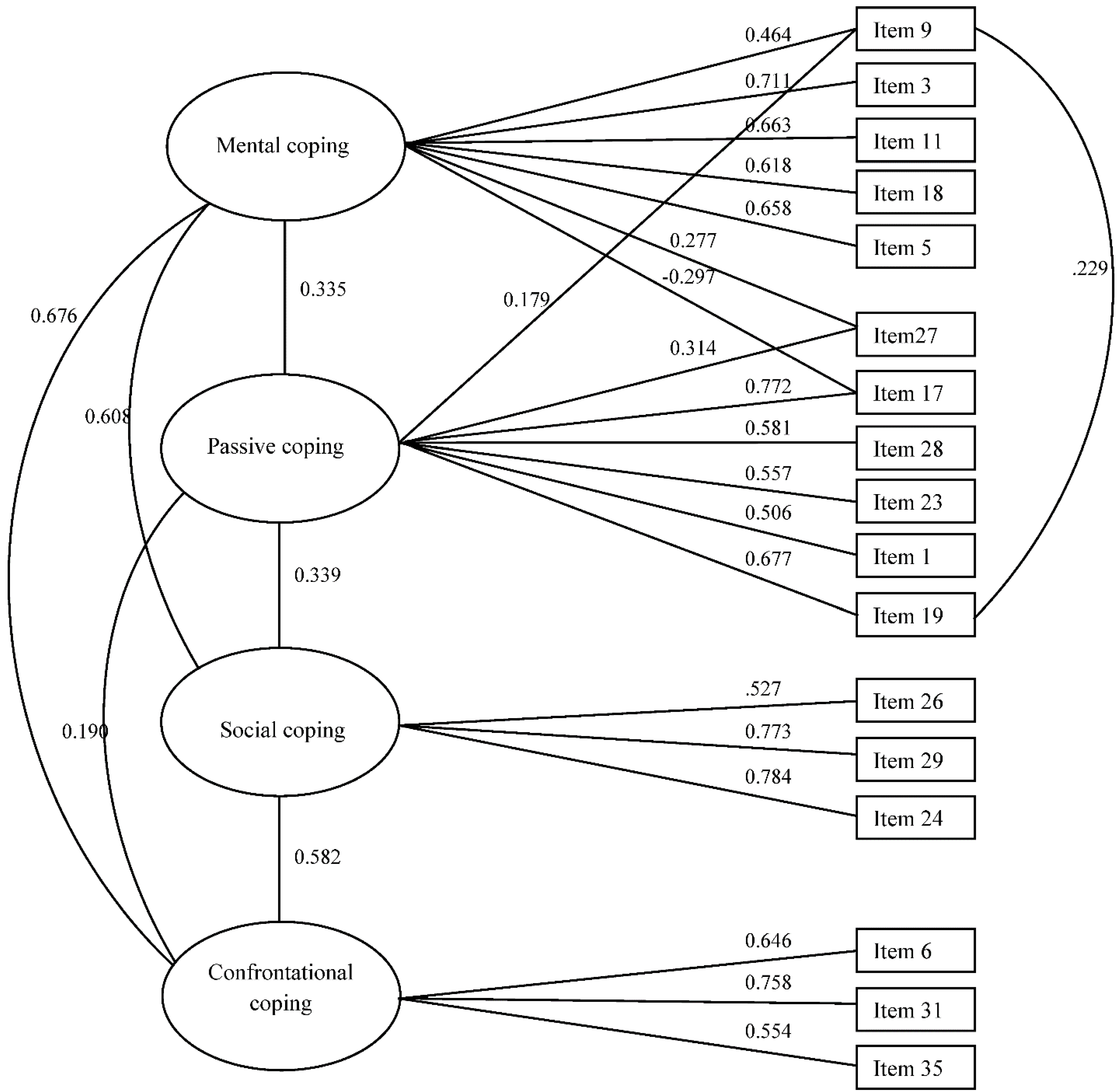

3.2.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

| Model | χ2 | df | χ2/df | Δχ2 | Δdf | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | SRMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st solution | 240.16 *** | 113 | 2.13 | - | - | 0.868 | 0.841 | 0.073 ** (CI 90%: 0.060–0.086) | 0.079 |

| 2nd solution | 189.87 *** | 109 | 1.74 | 294.1*** | 9 | 0.916 | 0.895 | 0.059 (CI 90%: 0.045–0.073) | 0.058 |

| Coping categories | α | Ω | GLB | Test-retest r |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mental coping | 0.7 | 0.72 | 0.74 | 0.65 * |

| Passive coping | 0.73 | 0.73 | 0.8 | 0.47 * |

| Social coping | 0.73 | 0.75 | 0.76 | 0.74 * |

| Confrontational coping | 0.68 | 0.7 | 0.73 | 0.60 * |

3.2.3. Test-Retest Reliability

3.2.4. Discriminant Validity

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lazarus, R.S.; Folkman, S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Folkman, S.; Lazarus, R.S. An analysis of coping in a middle-aged community sample. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1980, 21, 219–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skinner, E.A.; Edge, K.; Altman, J.; Sherwood, H. Searching for the structure of coping: A review and critique of category systems for classifying ways of coping. Psychol. Bull. 2003, 129, 216–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Völlink, T.; Bolman, C.A.W.; Eppingbroek, A.; Dehue, F. Emotion-Focused Coping Worsens Depressive Feelings and Health Complaints in Cyberbullied Children. J. Criminol. 2013, 2013, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreou, E. Bully/Victim Problems and their Association with Coping Behaviour in Conflictual Peer Interactions Among School-age Children. Educ. Psychol. 2001, 21, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bijttebier, P.; Vertommen, H. Coping with peer arguments in school-age children with bully/victim problems. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 1998, 68, 387–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craig, W.; Pepler, D.; Blais, J. Responding to Bullying: What Works? Sch. Psychol. Int. 2007, 28, 465–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, S.C.; Boyle, J.M.E. Appraisal and coping strategy use in victims of school bullying. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2004, 74, 83–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kristensen, S.M.; Smith, P.K. The use of coping strategies by Danish children classed as bullies, victims, bully/victims, and not involved, in response to different (hypothetical) types of bullying. Scand. J. Psychol. 2003, 44, 479–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahady Wilton, M.M.; Craig, W.M.; Pepler, D.J. Emotional Regulation and Display in Classroom Victims of Bullying: Characteristic Expressions of Affect, Coping Styles and Relevant Contextual Factors. Soc. Dev. 2000, 9, 227–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, D.G.; Hodges, E.V.E.; Egan, S.K.; Juvonen, J.; Graham, S. Determinants of chronic victimization by peers: A review and new model of family influence. In Peer Harass. Sch. Plight Vulnerable Vict; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2001; pp. 73–104. [Google Scholar]

- Skrzypiec, G.; Slee, P.; Murray-Harvey, R.; Pereira, B. School bullying by one or more ways: Does it matter and how do students cope? Sch. Psychol. Int. 2011, 32, 288–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalski, R.M.; Giumetti, G.W.; Schroeder, A.N.; Lattanner, M.R. Bullying in the digital age: A critical review and meta-analysis of cyberbullying research among youth. Psychol. Bull. 2014, 140, 1073–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, M.A.; Spears, B.; Slee, P.; Butler, D.; Kift, S. Victims’ perceptions of traditional and cyberbullying, and the psychosocial correlates of their victimisation. Emot. Behav. Difficulties 2012, 17, 389–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perren, S.; Dooley, J.; Shaw, T.; Cross, D. Bullying in school and cyberspace: Associations with depressive symptoms in Swiss and Australian adolescents. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2010, 4, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ybarra, M.L.; Mitchell, K.J. Youth engaging in online harassment: associations with caregiver-child relationships, Internet use, and personal characteristics. J. Adolesc. 2004, 27, 319–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hinduja, S.; Patchin, J.W. Bullying, cyberbullying, and suicide. Arch. Suicide Res. 2010, 14, 206–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, S.K.; O’Donnell, L.; Stueve, A.; Coulter, R.W.S. Cyberbullying, school bullying, and psychological distress: A regional census of high school students. Am. J. Public Health 2012, 102, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinduja, S.; Patchin, J.W. Offline Consequences of Online Victimization. J. Sch. Violence 2007, 6, 89–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, R.; Elipe, P.; Mora-Merchán, J.A.; Genta, M.L.; Brighi, A.; Guarini, A.; Smith, P.K.; Thompson, F.; Tippett, N. The emotional impact of bullying and cyberbullying on victims: A European cross-national study. Aggress. Behav. 2012, 38, 342–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gradinger, P.; Strohmeier, D.; Spiel, C. Traditional bullying and cyberbullying: Identification of risk groups for adjustment problems. Z. Psychol. Psychol. 2009, 217, 205–213. [Google Scholar]

- Ševčíková, A.; Šmahel, D.; Otavová, M. The perception of cyberbullying in adolescent victims. Emot. Behav. Difficulties 2012, 17, 319–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Eijnden, R.; Vermulst, A.; van Rooij, T.; Meerkerk, G.J. Monitor Internet en Jongeren: Pesten op Internet en het Psychosociale Welbevinden van Jongeren; IVO: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2006. (In Dutch) [Google Scholar]

- Black, C.; Wilson, G.T. Assessment of eating disorders: Interview versus questionnaire. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 1996, 20, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gravetter, F.J.; Forzano, L.B. Research Methods for the Behavioral Sciences; Wadsworth/Thomson Learning: Belmont, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Parris, L.; Varjas, K.; Meyers, J.; Cutts, H. High School Students’ Perceptions of Coping With Cyberbullying. Youth Soc. 2011, 44, 284–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compas, B.E.; Connor-Smith, J.K.; Saltzman, H.; Thomsen, A.H.; Wadsworth, M.E. Coping with stress during childhood and adolescence: Problems, progress, and potential in theory and research. Psychol. Bull. 2001, 127, 87–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roth, S.; Cohen, L.J. Approach, avoidance, and coping with stress. Am. Psychol. 1986, 41, 813–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kochenderfer-Ladd, B.; Skinner, K. Children’s coping strategies: Moderators of the effects of peer victimization? Dev. Psychol. 2002, 38, 267–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Šleglova, V.; Cerna, A. Cyberbullying in Adolescent Victims: Perception and Coping. Cyberpsychol. J. Psychosoc. Res. Cybersp. 2011, 5. Article 4. Available online: www.cyberpsychology.eu/view.php?cisloclanku=2011121901&article=4. [Google Scholar]

- Völlink, T.; Bolman, C.A.W.; Dehue, F.; Jacobs, N.C.L. Coping with Cyberbullying: Differences Between Victims, Bully-victims and Children not Involved in Bullying. J. Community Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2013, 23, 7–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandebosch, H.; Van Cleemput, K. Cyberbullying among youngsters: Profiles of bullies and victims. New Media Soc. 2009, 11, 1349–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalski, R.M.; Limber, S.P. Electronic Bullying Among Middle School Students. J. Adolesc. Health 2007, 41, S22–S30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sveinbjornsdottir, S.; Thorsteinsson, E.B. Adolescent coping scales: A critical psychometric review. Scand. J. Psychol. 2008, 49, 533–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Ouytsel, J.; Walrave, M.; Vandebosch, H. Correlates of Cyberbullying and How School Nurses Can Respond. NASN Sch. Nurse 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noar, S.M.; Benac, C.N.; Harris, M.S. Does tailoring matter? Meta-analytic review of tailored print health behavior change interventions. Psychol. Bull. 2007, 133, 673–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dehue, F.; Bolman, C.; Völlink, T. Cyberbullying: Youngsters” experiences and parental perception. Cyberpsychol. Behav. 2008, 11, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aricak, T.; Siyahhan, S.; Uzunhasanoglu, A.; Saribeyoglu, S.; Ciplak, S.; Yilmaz, N.; Memmedov, C. Cyberbullying among Turkish adolescents. Cyberpsychol. Behav. 2008, 11, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, P.; Mahdavi, J.; Carvalho, M.; Tippett, N. An investigation into cyberbullying, its forms, awareness and impact, and the relationship between age and gender in cyberbullying. Available online: http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20130401151715/http://www.education.gov.uk/publications/eOrderingDownload/RBX03-06.pdf (accessed on 5 December 2013).

- Jacobs, N.C.L.; Goossens, L.; Dehue, F.; Völlink, T.; Lechner, L. Dutch Cyberbullying Victims’ Experiences, Perceptions, Attitudes and Motivations Related to (Coping with) Cyberbullying: Focus Group Interviews. Societies 2015, 5, 43–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, C. Conceptualization and measurement of coping during adolescence: A review of the literature. J. Nurs. Scholarsh 2010, 42, 166–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naylor, P.; Cowie, H. The effectiveness of peer support systems in challenging school bullying: The perspectives and experiences of teachers and pupils. J. Adolesc. 1999, 22, 467–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kokkinos, C.M.; Antoniadou, N.; Dalara, E.; Koufogazou, A.; Papatziki, A. Cyber-Bullying, Personality and Coping among Pre-Adolescents. Int. J. Cyber Behav. Psychol. Learn. 2013, 3, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharp, S. How much does bullying hurt? The effects of bullying on the personal wellbeing and educational progress of secondary aged students. Educ. Child Psychol. 1995, 12, 81–88. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, J.; Gillies, R.M. How Adolescents Cope With Bullying. Aust. J. Guid. Couns. 2004, 14, 195–210. [Google Scholar]

- Frydenberg, E.; Lewis, R. The Adolescent Coping Scale: Administrator’s Manual; Australian Council for Educational Research: Melbourne, Australia, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Bijstra, J.O.; Jackson, S.; Bosma, H.A. De Utrechtse Coping Lijst voor Adolescenten. Kind En Adolesc. 1994, 15, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Causey, D.L.; Dubow, E.F. Development of a self-report coping measure for elementary school children. J. Clin. Child Psychol. 1992, 21, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandstrom, M.J. Pitfalls of the peer world: How children cope with common rejection experiences. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2004, 32, 67–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pozzoli, T.; Gini, G. Active Defending and Passive Bystanding Behavior in Bullying: The Role of Personal Characteristics and Perceived Peer Pressure. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2010, 38, 815–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terranova, A.; Harris, J.; Kavetski, M.; Oates, R. Responding to Peer Victimization: A Sense of Control Matters. Child Youth Care Forum 2011, 40, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, S.; De Young, A.; Toon, C.; Bond, S. Longitudinal examination of the associations between emotional dysregulation, coping responses to peer provocation, and victimisation in children. Aust. J. Psychol. 2009, 61, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visconti, K.J.; Sechler, C.M.; Kochenderfer-Ladd, B. Coping with peer victimization: The role of children’s attributions. Sch. Psychol. Q. 2013, 28, 122–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shelley, D.; Craig, W.M. Attributions and Coping Styles in Reducing Victimization. Can. J. Sch. Psychol. 2009, 25, 84–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayers, T.S.; Sandler, I.N. Manual for the Children’s Coping Strategies Checklist and the How I Coped Under Pressure Scales. Available online: http://prc.asu.edu/docs/CCSC-HICUPS%20%20Manual2.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2014).

- Kochenderfer-Ladd, B.; Pelletier, M.E. Teachers’ views and beliefs about bullying: Influences on classroom management strategies and students’ coping with peer victimization. J. Sch. Psychol. 2008, 46, 431–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kochenderfer-Ladd, B. Peer Victimization: The Role of Emotions in Adaptive and Maladaptive Coping. Soc. Dev. 2004, 13, 329–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, C.W.C.; Frydenberg, E. Coping in the Cyberworld: Program Implementation and Evaluation—A Pilot Project. Aust. J. Guid. Couns. 2009, 19, 196–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodge, J.; Frydenberg, E. Cyber-Bullying in Australian Schools: Profiles of Adolescent Coping and Insights for School Practitioners. Aust. Educ. Dev. Psychol. 2007, 24, 45–58. [Google Scholar]

- Murray-harvey, R.; Skrzypiec, G.; Slee, P.T. Effective and Ineffective Coping With Bullying Strategies as Assessed by Informed Professionals and Their Use by Victimised Students. Aust. J. Guid. Couns. 2012, 22, 122–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodge, J. Exploring the measurement and structure of children’s coping through the development of a short form of coping. Aust. Educ. Dev. Psychol. 2006, 23, 35–45. [Google Scholar]

- Waasdorp, T.E.; Bagdi, A.; Bradshaw, C.P. Peer Victimization Among Urban, Predominantly African American Youth: Coping With Relational Aggression Between Friends. J. Sch. Violence 2009, 9, 98–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Southam-gerow, K.L.; Goodman, M.A. The regulating role of negative emotions in children’s coping with peer rejection. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2010, 41, 515–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amirkhan, J.H. A factor analytically derived measure of coping: The Coping Strategy Indicator. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1990, 59, 1066–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palladino, B.E.; Nocentini, A.; Menesini, E. Online and offline peer led models against bullying and cyberbullying. Psicothema 2012, 24, 634–639. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Garnefski, N.; Rieffe, C.; Jellesma, F.; Terwogt, M.M.; Kraaij, V. Cognitive emotion regulation strategies and emotional problems in 9–11-year-old children: The development of an instrument. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2007, 16, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jellesma, F.C.; Verhulst, A.F.; Utens, E.M.W.J. Cognitive coping and childhood anxiety disorders. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2010, 19, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garnefski, N.; Kraaij, V.; Spinhoven, P. Negative life events, cognitive emotion regulation and emotional problems. Pers. Individ. Dif. 2001, 30, 1311–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayers, T.S.; Sandier, I.N.; West, S.G.; Roosa, M.W. A Dispositional and Situational Assessment of Children’s Coping: Testing Alternative Models of Coping. J. Pers. 1996, 64, 923–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmer-Gembeck, M.J.; Lees, D.; Skinner, E.A. Children’s emotions and coping with interpersonal stress as correlates of social competence. Aust. J. Psychol. 2011, 63, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampel, P.; Dickow, B.; Petermann, F. Reliability and validity of the German Coping Questionnaire for Children and Adolescents (Ger-man). Z. Diff. Diagn. Psychol. 2002, 23, 273–289. [Google Scholar]

- Hampel, P.; Manhal, S.; Hayer, T. Direct and relational bullying among children and adolescents: Coping and psychological adjustment. Sch. Psychol. Int. 2009, 30, 474–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roger, D.; Jarvis, G.; Najarian, B. Detachment and coping: The construction and validation of a new scale for measuring coping strategies. Pers. Individ. Dif. 1993, 15, 619–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grennan, S.; Woodhams, J. The impact of bullying and coping strategies on the psychological distress of young offenders. Psychol. Crime Law 2007, 13, 487–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halstead, M.; Johnson, S.B.; Cunningham, W. Measuring Coping in Adolescents: An Application of the Ways of Coping Checklist. J. Clin. Child. Psychol. 1993, 22, 337–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dise-Lewis, J.E. The Life Events and Coping Inventory: An assessment of stress in children. Psychosom. Med. 1988, 50, 484–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olafsen, R.N.; Viemerö, V. Bully/victim problems and coping with stress in school among 10- to 12-year-old pupils in Åland, Finland. Aggress. Behav. 2000, 26, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodge, J.; Feldman, S.S. Avoidant coping as a mediator between appearance-related victimization and self-esteem in youn Asutralian adolescents. Br. J. Dev. Psychol. 2007, 25, 633–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassidy, T.; Long, C. Problem-solving style, stress and psychological illness: Development of a multifactorial measure. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 1996, 35, 265–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cassidy, T.; Taylor, L. Coping and psychological distress as a function of the bully victim dichotomy in older children. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 2005, 8, 249–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carver, C.S.; Scheier, M.F.; Weintraub, J.K. Assessing coping strategies: A theoretically based approach. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1989, 56, 267–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newman, M.L.; Holden, G.W.; Delville, Y. Coping With the Stress of Being Bullied: Consequences of Coping Strategies Among College Students. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folkman, S.; Lazarus, R.S. If it changes it must be a process: Study of emotion and coping during three stages of a college examination. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1985, 48, 150–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Remillard, A.M.; Lamb, S. Adolescent Girls’ Coping With Relational Aggression. Sex Roles 2005, 53, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmivalli, C.; Karhunen, J.; Lagerspetz, K.M.J. How do the victims respond to bullying? Aggress. Behav. 1996, 22, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puhl, R.M.; Luedicke, J. Weight-based victimization among adolescents in the school setting: Emotional reactions and coping behaviors. J. Youth Adolesc. 2012, 41, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harper, C.R.; Parris, L.N.; Henrich, C.C.; Varjas, K.; Meyers, J. Peer Victimization and School Safety: The Role of Coping Effectiveness. J. Sch. Violence 2012, 11, 267–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenenbaum, L.S.; Varjas, K.; Meyers, J.; Parris, L. Coping strategies and perceived effectiveness in fourth through eighth grade victims of bullying. Sch. Psychol. Int. 2011, 32, 263–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machmutow, K.; Perren, S.; Sticca, F.; Alsaker, F.D. Peer victimisation and depressive symptoms: Can specific coping strategies buffer the negative impact of cybervictimisation? Emot. Behav. Difficulties 2012, 17, 403–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machmutow, K.; Perren, S. Coping with cyberbullying: Successful and unsuccessful coping strategies. In Poster presented at the 3rd COST workshop on cyberbullying, Turku, Finland, 13 May 2011.

- Jäger, T.; Jäger, R.S. LAPSuS: Landauer Anti-Gewalt-Programm für Schülerinnen und Schüler; Zentrum für Empirische Pädagogische Forschung: Landau, Germany, 1996. (In German) [Google Scholar]

- Riebel, J.; Jäger, R.S.; Fischer, U.C. Cyberbullying in Germany—An exploration of prevalence, overlapping with real life bullying and coping strategies. Psychol. Sci. Q. 2009, 51, 298–314. [Google Scholar]

- Machackova, H.; Cerna, A.; Sevcikova, A.; Dedkova, L.; Daneback, K. Effectiveness of coping strategies for victims of cyberbullying. Cyberpsychol. J. Psychosoc. Res. Cybersp. 2013, 7. Article 5. Available online: http://www.cyberpsychology.eu/view.php?cisloclanku=2014012101&article=5 (accessed on 30 July 2014). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perren, S.; Corcoran, L.; Cowie, H.; Dehue, F.; Garcia, D.; Mc Guckin, C. Cyberbullying and traditional bullying in adolescence: Differential roles of moral disengagement, moral emotions, and moral values. Eur. J. Dev. Psychol. 2012, 9, 195–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, S.C.; Boyle, J.M.E.; Warden, D. Help seeking amongst child and adolescent victims of peer-aggression and bullying: The influence of school-stage, gender, victimisation, appraisal, and emotion. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2004, 74, 375–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patchin, J.W.; Hinduja, S. Bullies Move Beyond the Schoolyard: A Preliminary Look at Cyberbullying. Youth Violence Juv. Justice 2006, 4, 148–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, M.; Dalgleish, J. Cyberbullying: Experiences, impacts and coping strategies as described by Australian young people. Youth Stud. Aust. 2010, 29, 51–59. [Google Scholar]

- Hunter, S.C.; Mora-Merchan, J.; Ortega, R. The Long-Term Effects of Coping Strategy Use in Victims of Bullying. Span. J. Psychol. 2004, 7, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanetsuna, T.; Smith, P.K. Pupil Insights into Bullying, and Coping with Bullying—A Bi-National Study in Japan and England. J. Sch. Violence 2002, 1, 5–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, P.K.; Shu, S. What Good Schools can Do About Bullying: Findings from a Survey in English Schools After a Decade of Research and Action. Childhood 2000, 7, 193–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, S.C.; Boyle, J.M.E. Perceptions of control in the victims of school bullying: The importance of early intervention. Educ. Res. 2002, 44, 323–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naylor, P.; Cowie, H.; Rey, R. Coping strategies of secondary school children in response to being bullied. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2001, 6, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schenk, A.M.; Fremouw, W.J. Prevalence, Psychological Impact, and Coping of Cyberbully Victims Among College Students. J. Sch. Violence 2012, 11, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elledge, L.C.; Cavell, T.A.; Ogle, N.T.; Newgent, R.A.; Faith, M.A. History of peer victimization and children’s response to school bullying. Sch. Psychol. Q. 2010, 25, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochenderfer, B.J.; Ladd, G.W. Victimized children’s responses to peers’ aggression: Behaviors associated with reduced versus continued victimization. Dev. Psychopathol. 1997, 9, 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garnefski, V.; Kraaij, N.; Spinhoven, P. Manual for the Use of the Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire; DATEC: Leidorp, The Netherlands, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, N.C.L.; Völlink, T.; Dehue, F.; Lechner, L. Procesevaluatie van Online Pestkoppenstoppen; Open University: Heerlen, The Netherlands, 2014. (In Dutch) [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, N.C.L.; Völlink, T.; Dehue, F.; Lechner, L. Online Pestkoppenstoppen: Systematic and theory-based development of a web-based tailored intervention for adolescent cyberbully victims to combat and prevent cyberbullying. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conway, J.M.; Huffcutt, A.I. A review and evaluation of exploratory factor analysis practices in organizational research. Organ Res. Methods 2003, 6, 147–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using SPSS, 3rd ed.; SAGE Publications Limited: Los Angeles, CA, USA; London, UK; New Delhi, India; Singapore, Singapore; Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg, M. Conceiving the Self; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S. Using Multivariate Statistics, 5th ed.; Allyn & Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Linting, M.; van der Kooij, A. Nonlinear principal components analysis with CATPCA: A tutorial. J. Pers. Assess. 2012, 94, 12–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linting, M.; Meulman, J.J.; Groenen, P.J.F.; van der Koojj, A.J. Nonlinear principal components analysis: Introduction and application. Psychol. Methods 2007, 12, 336–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kline, P. An Easy Guide to Factor Analysis; Routledge: London, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, D.L.; Gillaspy, J.A.; Purc-Stephenson, R. Reporting practices in confirmatory factor analysis: An overview and some recommendations. Psychol. Methods 2009, 14, 6–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kenny, D.A. Measuring Model Fit 2012. Available online: http://davidakenny.net/cm/fit.htm (accessed on 2 July 2014).

- Bollen, K.A. Structural Equations with Latent Variables; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle, J.L. Amos 20 User’s Guide; IBM: Chicago, IL, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S. Using Multivariate Statistics, 4th ed.; Allyn & Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Heirman, W.; Walrave, M. Assessing Concerns and Issues about the Mediation of Technology in Cyberbullying. Cyberpsychol. J. Psychosoc. Res. Cybersp. 2008, 2, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

© 2015 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jacobs, N.C.L.; Völlink, T.; Dehue, F.; Lechner, L. The Development of a Self-Report Questionnaire on Coping with Cyberbullying: The Cyberbullying Coping Questionnaire. Societies 2015, 5, 460-491. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc5020460

Jacobs NCL, Völlink T, Dehue F, Lechner L. The Development of a Self-Report Questionnaire on Coping with Cyberbullying: The Cyberbullying Coping Questionnaire. Societies. 2015; 5(2):460-491. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc5020460

Chicago/Turabian StyleJacobs, Niels C.L., Trijntje Völlink, Francine Dehue, and Lilian Lechner. 2015. "The Development of a Self-Report Questionnaire on Coping with Cyberbullying: The Cyberbullying Coping Questionnaire" Societies 5, no. 2: 460-491. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc5020460

APA StyleJacobs, N. C. L., Völlink, T., Dehue, F., & Lechner, L. (2015). The Development of a Self-Report Questionnaire on Coping with Cyberbullying: The Cyberbullying Coping Questionnaire. Societies, 5(2), 460-491. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc5020460