1. Introduction

Dehumanization, the process of attributing less-than-human or non-human attributes to members of a group, facilitates several outcomes. First, it permits those in dominant or in-group positions to explain the actions, behaviours and attributes of those who are being dehumanized as natural or essential. This construction of natural inhumanness then permits treatment that would normally not be permissible if applied to real humans. This latter outcome has implications for the management of bodies that go beyond simple questions of discipline or brutality; it also permits the management of dehumanized bodies that have been rendered docile in ways that are optimally efficient for the ‘real’ humans who must deal with them.

For example, in Nazi Germany, people with disabilities, mental health concerns, homosexuals, immigrants, and of course, Jewish people were constructed as dangerous because they were seen to be dirty, dependent and possessed of different, vermin-like bodies that did not belong to the natural body social and that in fact threatened it [

1]. For these groups, this construction at the same time obfuscated the reality that their position as outsiders resulted from historical and contemporary practices that left them with no choice but to live in institutions, ghettos or to interact with others as abject outsiders [

2]. In turn, this made starvation, degradation and immunity to guilt or compassion predictable outcomes of the dehumanizing process. In the case of the Jewish holocaust, this dehumanizing process made it possible for non-Jewish guards and citizens and—as survivor narratives tell us—even at times for some Jews in the camps to distance themselves from what was happening and to assure themselves that the fate of the fully dehumanized inmate could be avoided [

3]. In this aspect of dehumanization, individual traits are erased and the individual comes to be seen as the embodiment of a group that is not fully human or present, that has neither the capacity nor the desire to be human, and hence need not, indeed, cannot be taken into account as a member of one’s own species [

3]. Further, this erasure permitted the treatment of disabled, sexually different, immigrant and Jewish people that was not only brutal and inhumane, but that was predicated on levels of efficiency that could only apply to the management of bodies that were constructed as not-human, such as transporting people in cars designed for cattle, or housing them in warehouses more suited to objects than sentient beings

2. In this paper, I discuss the management and control of the bodies of intellectually-disabled children and young adults in terms of this kind of dehumanization, arguing that the brutal conditions under which purportedly mentally defective children were kept in one specific institution, the Michener Center in Alberta, Canada, reflects dehumanizing processes that were not only violent and unfeeling, but that also facilitated efficiency, a desirable outcome in modernity.

Dehumanization is also related to the problem of

matter out of place in modernity; the unruly, abject body of the Other acts as a challenge to the order and predictability of normalcy [

4]. Both Hughes [

2] and Savage [

5] argue that the definition of certain bodies as matter out of place is a particularly modernist obsession wherein order and predictability are synonymous with goodness, while difference or matter out of its normative place is seen as a moral flaw. These aspects of dehumanization: unruliness, embodied difference and the problem of matter out of place [

6], have been particularly problematic for people with intellectual disabilities, whose unruly minds and bodies do not fit within normative orders of modern civil societies. In particular this disjuncture became heightened in the 20

th century with the increasing needs of industrialized capitalism, which in turn gave rise to congregated populations through such things as prisons, hospitals, and of particular relevance to this paper, public education [

7,

8]. With the rise of public schooling, for the first time, the unruly bodies of intellectually disabled people became visible, and disciplinary mechanisms arose to separate the human/potentially productive child from the subhuman/unproductive one [

9,

10]. The increasing visibility of the undocile body of the uneducable child, and the narrowing definition of good citizenry that accompanied modern, disciplinary societies [

11,

12] help to account for the movement towards sequestering the abject bodies of intellectually disabled people during the last century into a vast network of special institutions [

10]. This separation of the undocile, unproductive child’s body from the good, productive citizen can also account for the tremendous neglect and abuse that occurred within those institutions under the name of care; because these bodies were without value, it was not a far stretch to treat them in ways more normatively acceptable to the treatment of animals than of humans [

13].

The following discussion draws upon oral history interviews with 22 survivors

3 of lengthy internments (between the mid-1950s and early 1980s) in an institution for mental defectives, the Michener Center in Red Deer, Canada. This institution at its height in the late 1970s housed over 2,400 children and adults, most of whom entered the institution in early childhood, remaining for decades, often for life

4. My analysis is also informed by interviews with three ex-workers, archival materials including ward records, architectural drawings, photographs, annual reports and unusual incident files, and a tour of the facilities made in 2001.

The Michener Center opened in 1923 in an imposing three-storey brick building located in parkland just outside the small city of Red Deer, Alberta, as part of the great early 20

th century move in industrialized countries to institutionalize the unruly, unproductive bodies of those deemed to be mentally defective. Prior to its opening, children with intellectual disabilities had either remained in their communities, very often without services of any kind, or they were housed along with individuals labeled as mentally ill in places like the Mental Hospital in Brandon, Manitoba, situated two provinces and almost a thousand kilometers from the Alberta border. Thus, the Michener institution was lauded as a humane solution and as progressive because it segregated the “mentally retarded from the mentally ill”, moved children closer to their families, and purportedly shifted the focus of services from incarceration to education [

14]. Despite these claims to humanitarianism and education for reintegration as productive citizens, however, survivors’ narratives, ex-workers descriptions and the archival record instead illuminate that education and humane treatment were not the institutional order of the day. Rather, multiple avenues and outcomes of dehumanization operated in the institution, and these dehumanizing operations were accomplished through systemic (and systematic) ways of treating and perceiving the bodies of mentally defective inmates. I speculate here that these operations of dehumanization were in many ways measures of efficiency that facilitated the ease of care for paid, normate

5 workers. Further, these dehumanizing actions facilitated an historical and indeed persistent notion of the subhuman mental defective as undeserving of resources and a burden on the social body.

2. Dehumanization and Unruly Bodies

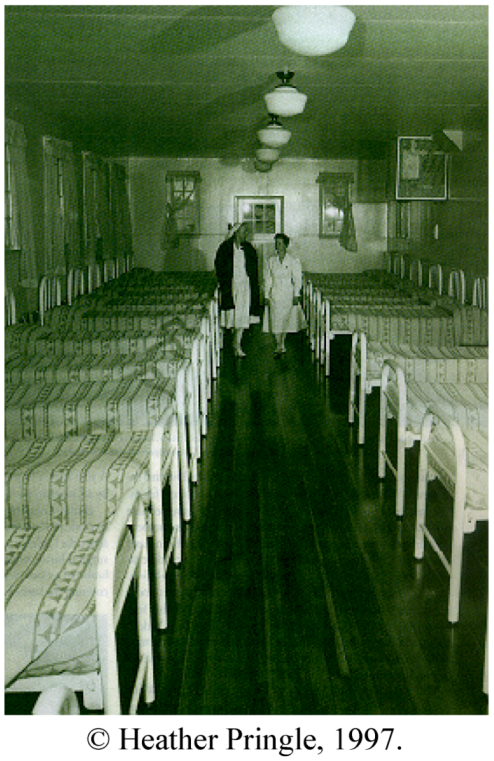

Dehumanization naturalizes the outsider status of certain people by erasing the individuality of the Other, producing them as a category rather than a person. Inside the institution, order, routine, regimentation and an erasure of inmates’ individuality was a major component and goal of daily life, used both to repress and produce the bodies of inmates. To illustrate, in a photograph taken in the late-1950s, a dorm comprised of a simple room without dividers houses two long rows of metal bedsteads, each with a striped coverlet (

Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Orderly beds in a staged photo of a 1950s Michener Center dormitory.

Figure 1.

Orderly beds in a staged photo of a 1950s Michener Center dormitory.

Reportedly, Dr. LeVann, the institutional Superintendent, was very particular that the stripes on these bed-covers should line up perfectly to create an atmosphere of precision and order undisturbed by the unruly bodies of actual inmates; once the rooms were cleaned, inmates were not permitted to return to them until bedtime [

15]. Such obsessions reflect an overarching perception that the inmates in all their embodied unruliness were expected to be subordinated to institutional regimes and were in fact seen as a blight upon the institutional order. They also reflect a normative understanding of how modern, productive and civilized bodily matter should be: orderly, calm, clean and docile. More importantly, however, depictions and arrangements of an idealized institutionalized space convey ideas about how a normal human’s space and life should look, and through the absence of non-compliant bodies, how little those bodies fit within this schema.

Juxtaposed against this normative ideal of the human body as orderly and docile, the descriptions that inmates provide about their daily experiences show us just how far outside this framing their bodies were. Days at Michener were characterized by long, painfully dull stretches of time, interrupted by brief, intense bursts of activity. A typical day began early, and followed the same numbing routine each day. Harvey Brown

6, who lived in the institution from the age of 12 to 21, describes how his childhood days unfolded:

Got up at 6:30. Had breakfast at 7:00. Made your bed and all that stuff. Had inspection. Went to school at 8:30. Came back for lunch at twenty to 12:00. Sat around. Supper at 5:00 or quarter to 5:00 and then a bath or shower at 6:30. Sat around and watched T.V. until 9 o’clock and then you went to bed.

These routines were adhered to relentlessly, and it should also be noted that Harvey was one of the rare children to attend any kind of schooling in the institution. For most children, the diversion of a half day of schooling would not have been part of the daily routine. The recreational activities of sitting around and watching TV that Harvey describes occurred in common dayrooms that were 50 deep and 50 wide with tiled flooring and shiny white walls. These rooms were lit by large, bright, bare mesh-fortified windows, and in the corner of each room was a television (

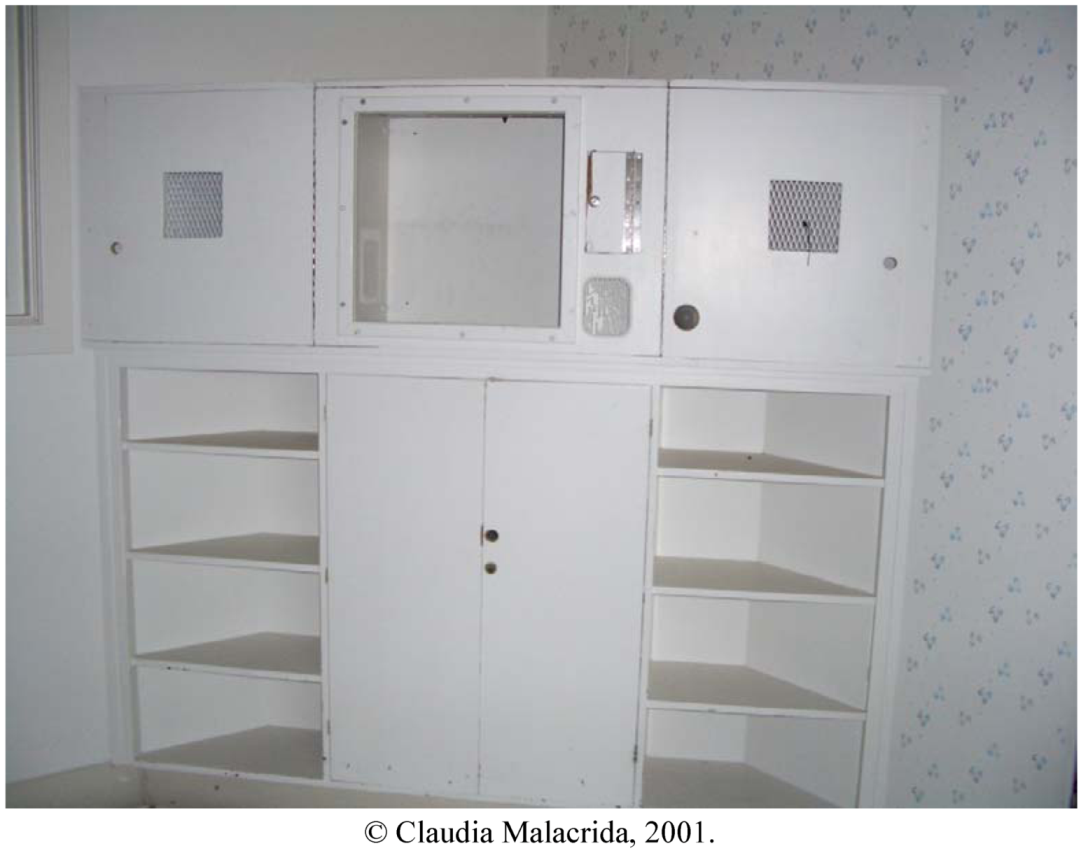

Figure 2) set built into a sturdy wooden, locked, mesh-covered cabinet.

Figure 2.

The locked television cabinet in a dayroom at Michener Center.

Figure 2.

The locked television cabinet in a dayroom at Michener Center.

According to survivors, although dayrooms were generally crowded, there were few chairs for people to lounge in, so that very often people milled around aimlessly, sat or lay on the floors, leaned against walls or, in some cases, sat in wheelchairs or on the occasional hard chair in the rooms. The dayrooms, like all spaces on the campus, were locked, so that inmates needing to use the toilet would have to yell for someone to give them access to the facilities. As a result, incontinence and stench were part of everyday recreational life for inmates.

In discussing a typical day, Ray, who entered the institution at seven years of age and left at 25, described the dayroom in the following terms:

We would all go to the dayroom there. They would lock the door behind us and we all would be, some of us would sit on the floor, and some of us would sit on the chairs, because they didn’t have the…didn’t have very many chairs and we were sitting on floors.

These uncomfortable settings did not simply serve as brief holding areas where young people might spend a few minutes waiting to be taken somewhere more hospitable to learn or to rest or to play. Rather, once they had been toileted and fed, inmates were put into the dayrooms where they spent very long stretches of time. The lack of furniture or decoration in these rooms, and lack of comfort inmates were afforded, seems to reflect a belief that inmates’ bodies were not entitled, indeed, did not require a comfortable or pleasant place to sit, like any ordinary person might. Instead, these rooms were little more than holding tanks or warehouses, and could have as easily been used for storing objects as for housing human bodies.

Not only was the children’s comfort unimportant, but it also seems to have been assumed that these children would not require interaction and stimulus in order to grow and develop, perhaps because they were not expected to grow and develop like any normal human child. In describing her impressions of the dayrooms and the activities in them, ex-worker Evelyn Stephens says:

Most of the people were very drugged up, you know, I can’t think of anything more mind-numbing and monotonous and deadening than—and I felt that so often—the routines of the day. Everyone was just walking around, like the walking dead...people were sitting, pacing, rocking, watching T.V.

The hypermedicating of people in the institution represents a very modern form of dehumanization, in the Foucauldian sense. Here, rather than brutalizing inmates, the seemingly benign effects of modern psychopharmaceutical treatment operated as a much more efficient vehicle for maintaining the docility of otherwise unruly bodies. The institutional records are replete with entries about increased medication for unruly or demanding behavior, and they describe the sometimes heroic efforts required to make inmates comply with these medical protocols. By keeping inmates drugged and docile, the institution and its workers were able to erase resistance, and importantly, to undermine the expression of (human) personalities amongst inmates.

Ex-worker Coral James’ description echoes Evelyn’s insights on the dayrooms; she noted nursing staff spent most of their days locked behind the doors and windows of the nursing station counting meds and charting, and she was unable to recall staff spending any time in the dayrooms interacting with inmates. Instead, her job was to put those patients who were deemed capable into the dayroom (bed-patients in fact lived even more dehumanizing lives than the dayroom occupants) and leave them there until they needed feeding or toileting again, according to the needs of the institutional schedule rather than the individual’s bodily requirements. The dayrooms thus acted as a further tool of segregation and Othering of the bodies of unruly inmates; while the normate bodies of staff remained safely sequestered behind glass in the nursing station, inmates sprawled, crawled and rocked their days away in the foul, unruly, subhuman space of the dayroom.

3. Dehumanization and the Use of Space

Michel Foucault [

11,

16] has shown us convincingly that the spatial arrangements of buildings, public places and interiors are not simply constructed in ways that are haphazard or aesthetic, but they are also functional and political. In his work, we learn that modernity has been characterized by the development of large public institutions like Michener that are built and organized so as to exercise the surveillance over and control of large populations. For Foucault, this exercising of space and vision upon large congregations of docile bodies is a hallmark of modern disciplinary societies. Rather than brutally punish transgressors, modern disciplinary organizations work preventatively, through the organization of space and the practices of knowledgeable professionals, to keep people’s bodies and minds submissive and disciplined [

16]. Being able to view inmates, to measure their activities, and respond to their transgressions immediately with modern instruments such as the chart or the patient record that tracks every minute action, is a powerful tool of preventative discipline. The Panopticon, Foucault’s metaphor for these modern disciplinary practices, is more than simply a viewing tower or, in this case, a nursing station on a raised platform. Instead, it is a multi-modal set of practices that permits regulation through seeing, knowing, coding, recording and normalizing the bodies of those at the distal end of the gaze. The point for Foucault is that, even when inmates are not being watched, they come to learn that they must act as if they are being watched or could be caught at any potential moment, because their movements are not only constantly observable, but also because they are translated into a dossier, recorded and made visible through multiple means to others. The record stands as a further layer in disciplining unruly bodies, constructing patient/inmate identities as categories of people deemed as normal/not-normal, compliant/unruly, rather than as individuals [

16,

17,

18].

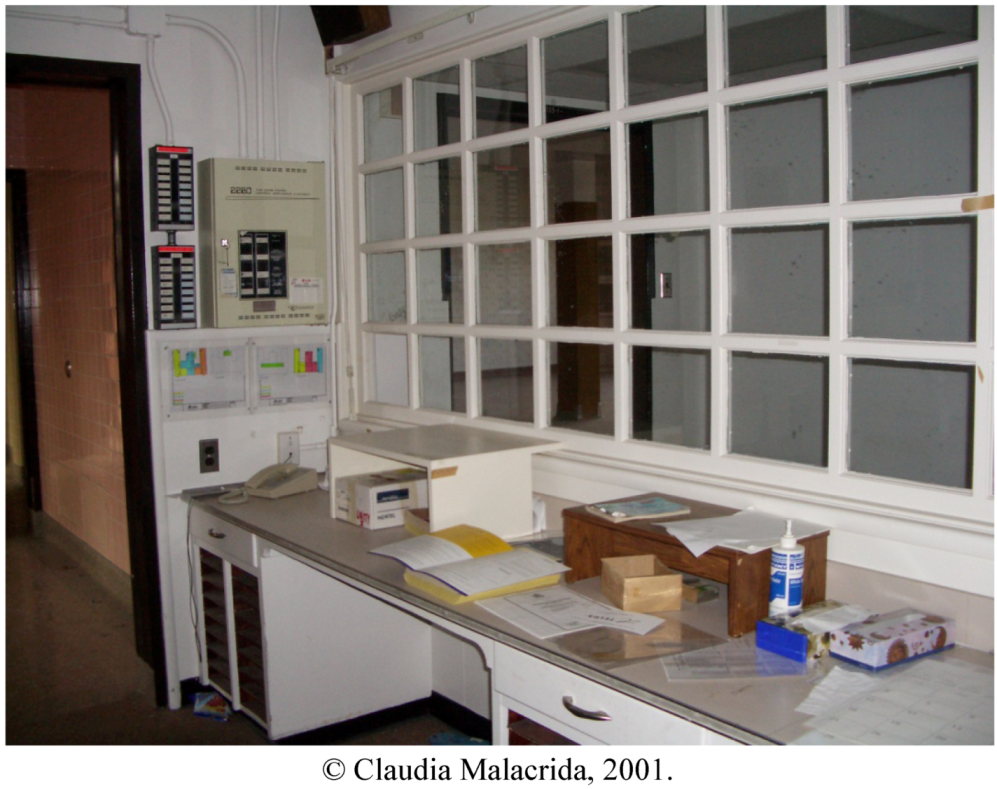

Of course these panoptic uses of space and categorization flourished in Michener Center. However, additional dehumanizing functions of spatial arrangements are also apparent from the survivor and ex-worker descriptions of the institution’s nursing stations, which were ubiquitous throughout the institution. Raised a foot or so off the main ground level, behind locked doors, the nursing stations overlooked the day areas in front of them and, to the side, the wards where inmates slept. Coral, who worked on several wards, describes the layout of these nursing stations:

The office was not unlike the one in [the film] “One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest.” Only I don’t remember the glass—there being a total glass front. But there was a lattice glass on three sides and there was a long counter and there were—so if I was looking out, I could look out into the dayroom area when I was looking forward from the office. Behind me, there would be charts, lots and lots of charts.

This enclosed space, raised above the rest of the rooms, and open visually onto all the patient spaces, of course operated as a kind of panopticon/watchtower (

Figure 3) from which inmates’ every movements were easily observed, their behaviours were readily recorded and charted, and their unruly actions could be speedily responded to by nursing staff, typically through physical restraint or by administering medications to sedate the offending inmate. The functions of the disciplinary gaze, emanating from the physical layout of the raised dais and paned windows of the nursing station, coupled with professional knowledge in the form of the openly visible array of patient charts and the swift retributive actions of staff towards resistant inmates, not only facilitated nursing observations, but they also produced a visual display of power and knowledge to inmates who could clearly see through the glass panes of the nursing station that they were being observed, controlled, and written into the institutional record.

Figure 3.

Nursing Station at Michener Center, taken looking out onto the dayroom.

Figure 3.

Nursing Station at Michener Center, taken looking out onto the dayroom.

In addition to these Foucauldian aspects of spatial practices, the dehumanizing functions of the Nursing Stations can be decoded as texts about purity and pollution. We can discern in the locked door, the glass enclosure and the raised dais that these were not only observational platforms, but they were also isolation chambers that segregated the clean and orderly bodies of staff from the disorderly and unclean bodies of inmates, in turn keeping staff from seeing inmates as human or from developing meaningful human relationships with them. As ex-worker Jim Sullivan described:

You didn’t have time. You couldn’t sit individually with the kid, you know, when kids are upset, you know the nine year old when he’s going to bed and he’s sort of upset. You couldn’t sit and chat with them because [there was] nowhere private, because you weren’t to bring these kids into the chart room or the staff room. That was sacred territory. And then the supervisors would come around at that time and if you were caught sitting, talking with a kid, you weren’t doing your job. You’re supposed to be cleaning, or writing your bloody reports.

In Jim’s description we hear how space and its organization led to dehumanization; certain spaces were only open to real humans, while freedom of movement, privacy, and the expression of human feelings were constructed as inappropriate for inmates and were the domain of staff alone. Further, as Jim insightfully points out, the distinction between the nursing station and the dayroom operated as a metaphor for the distinction between the sacred and the profane, constructing inmates as little more than dirt or clutter that would contaminate the sacred/clean space of the nursing station.

In practical terms, this institutionally routinized bodily segregation contributed to two kinds of emotional and psychological distancing. First, it produced a seemingly natural distance between staff and inmates and made it possible for staff to no longer see the inmates as real humans with concerns and feelings or rights to human considerations. Secondly, it facilitated staff members’ emotional distance from the often brutal and dehumanizing work that they did, enabling them to become accustomed to and accepting of practices that, under normal, human conditions would have been emotionally distressing or perhaps even impossible for workers to sustain.

4. Dehumanization and Ease of Care

Another aspect of dehumanization is that it not only naturalizes the outsider status of those it targets, but it actually justifies the prejudices and abuses of those in the powerful in-group. Using Nazism as an example

7, the systematic ill-treatment of people with disabilities, mental illness, members of sexual minorities, foreigners and Jews by the German authorities resulted in poverty, illness and lack of dignity for those people. In turn, these outcomes were used to legitimatize old abuses and develop new inhumane mistreatments—after all, so the logic went, they were drains on the social body or vermin who threatened it, hence they deserved nothing more than the ill-treatment they received [

19]. In the case of Michener Center, with its chronic over-crowding and staff shortages, inmates were treated with little dignity, housed in large warehouse-like spaces, fed, clothed and showered en masse, and often medicated so heavily as to erase their humanity. In the end, such dehumanization of the inmates was used to justify, or at the very least make it easier to feed, house, clean and regard inmates’ bodies with neglect or routine abuse because they seemed to deserve or require little more. For paid workers, dehumanization can make it possible to assume that human feelings of shame, decency, modesty or entitlement do not apply to inmates; in turn, such assumptions can make it seem reasonable to simply to toss someone unthinkingly into a wheelchair and leave them for hours or hose them down publicly in a communal shower.

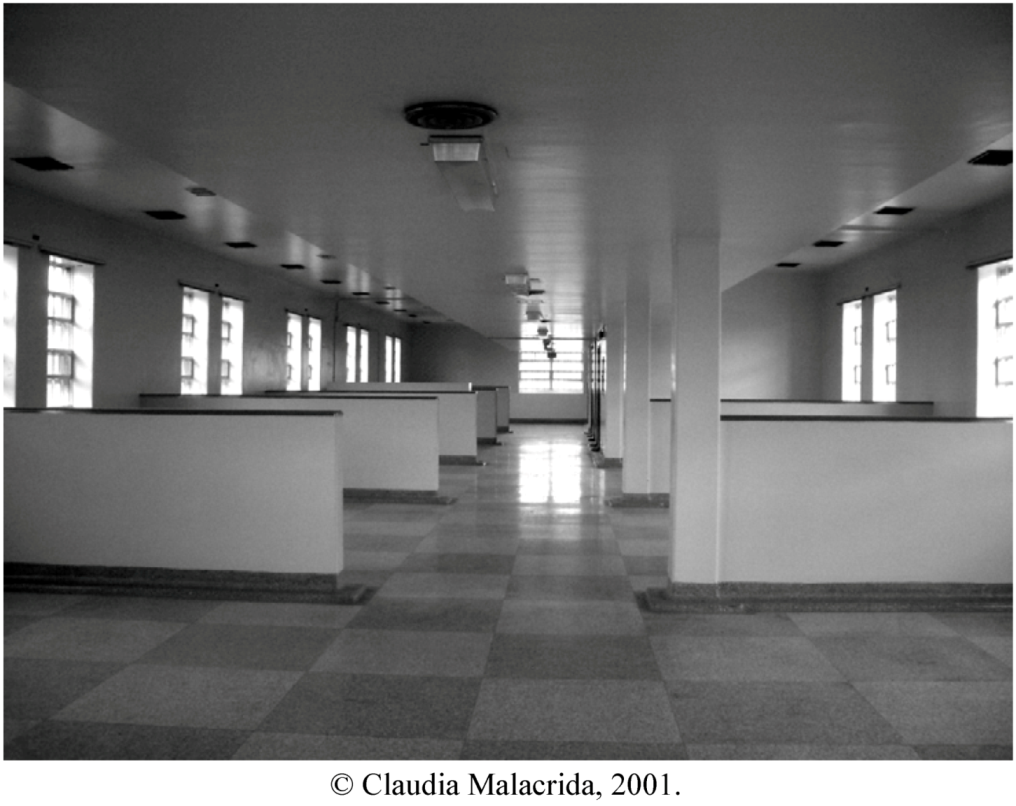

Survivors’ descriptions show us how negligence and dehumanization were built into the architecture of the institution. Coral, an ex-worker interviewed for this project, described inmates’ sleeping arrangements as follows:

The ward—the dorm—was a big wide open area and it ran the width of the building. And there were probably—there were pods. There would be one, two, three, four beds in a pod. And then there would be…a half wall and a pillar. And then four beds in the next pod with a half wall and a pillar. There was no privacy whatsoever. None whatsoever. So there must have been close to 50 people, I would think.

I have been able to observe these wards, and Coral’s estimates are correct. In a half-walled dorm housing almost 50 people, there were no curtains to separate the beds, no carpets on the floors, no bedside dressers on which to array personal items or photographs, no personal touches such as coloured bedspreads or stuffed toys on beds, no pictures on walls—indeed, there were no walls to speak of (

Figure 4). In one of the small rooms off each ward were clothing storage cupboards, approximately three feet tall by four or five feet wide, filled with cubbyholes with names taped to the front; these small spaces, no larger than one foot wide by one foot high and 18 inches deep, were where a child’s slippers or underclothing would be kept. Inmates’ outer clothing, provided by the institution, consisted of institutionally-sewn overalls for both sexes that obliterated any sense of personal identity or style. Thus, inmates’ bodies and their identities were produced as undifferentiated, as not-human through simple spatial and material practices.

Figure 4.

A typical ward, Michener Center.

Figure 4.

A typical ward, Michener Center.

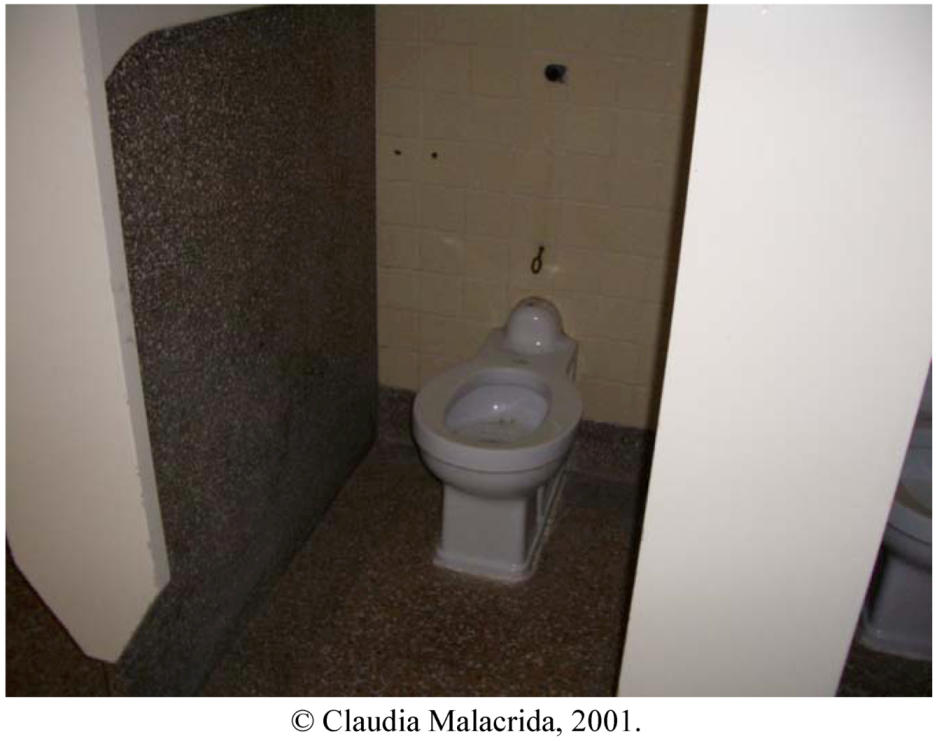

Close by the storage and sleeping room were several smaller rooms where daily hygiene took place. As with the sleeping quarters, the lack of privacy and the routinization of negligence were built directly into the architecture of these rooms. The first and most obvious thing that struck me when observing the toilets and showers was that they not only did not have doors, but that there was no evidence that they had ever

had them; there were no boreholes where latches and door hinges might once have existed (

Figure 5). This lack of doors on the toilets codes the privileging of facilitating the staff’s ability to supervise multiple inmates over any concerns for the privacy or dignity of inmates. In another example of the lack of privacy afforded to inmates, several rooms with elevated bathtubs in them also housed wash racks for equipment and a hopper for cleaning out bedpans, making it conceivable that one staff person might be emptying and cleaning soiled bedpans next to another person bathing a patient who required the more personalized care of these private baths rather than that afforded in the more public showers. In sum, the layout of these most intimate spaces makes it clear that the residents of the institution were conceived as other than human, not-human, and undeserving of the most basic bodily decencies.

Figure 5.

A more ‘private’ toilet, with walls, but no door.

Figure 5.

A more ‘private’ toilet, with walls, but no door.

Whether sleeping, toileting, bathing, dining, or spending so-called recreational time in dayrooms, privacy was an elusive property; bodies were handled, observed, and processed, always in groups, and always under the watchful eye of someone in a position of power. Ray Petrenko described a typical shower experience:

And if we went to take a shower, there was no private stalls. All there was was shower [heads] from one wall to the other. We had to stand in a long line in the hallways, and then we were paraded to go inside in the shower. There was no curtains or nothing. Everybody had to go into one stall, all at the same time. We would all line up and you had to parade with your clothes off and walk down the hallway and into the shower.

Former worker Evelyn Stephens confirms this description of the parade of naked bodies each morning, noting that the way the staff handled inmates’ bodies added to the dehumanization:

They’d be standing in the hallway naked waiting for you… There was like this long room with shower heads coming out of the wall. And umm, we had, the staff had rubber aprons, we had to get in there and scrub and (pause) and then, yeah, so they were showered that way and then we hosed them off there as well.

In similar ways to the showers, toileting was also typically accomplished collectively, at times that suited staff needs rather than inmates’ bodily urges. Thus, inmates were rounded up and taken en masse to toilets upon waking, after meals and prior to bedtime, regardless of personal choices or needs.

A final indignity, as Evelyn told me, and as I observed during my tour of the buildings, was that some of these toilets were mechanized so they could be flushed simultaneously. This would be accomplished by staff members, who used a pull-cord hanging near the door of the toileting room, thus maximizing workers’ efficiency and maintaining a hygienic distance between staff members, inmates and toilets. This last detail conveys a dystopian vision of a mechanized, routinized delivery of human services within the institution that completely denied the individuality, privacy, dignity, or humanity of the people being served; in this scenario, the utility of saving a few workers’ steps to flush individual toilets was seen as more important than the probability that at least some of the inmates would be forced to sit in their own—or their neighbor’s—stench until the staff member would decide that it was time to deliver that final, collective flush.

In these descriptions of bodies rendered inhuman, we can see that the modern, docile body is expanded upon; instead of simply producing a subject who is well-behaved and disciplined, dehumanization produces a subject who in many ways is not a subject at all. Rather, dehumanization produces a body without subjectivity that is perceived and treated as little more than a means to efficiency for those who must interact with it.

5. Dehumanization, Pollution and Hygiene

A fourth aspect of dehumanization draws on medical discourses of infection, contamination and disease, through which members of dominant groups come to see the bodies of Others as scourges and dangers to the cleanliness, decency, and health of the modern body social. In turn, this enables dominant group members to see cleansing or the actual removal/disinfection of the polluting body as desirable in terms of protecting the proper or hygienic social body [

2]. Thus, Nazi discourse spoke in terms of contamination and of the “necessity to sweep clean the world [of] sick people, cripples, psychologically immoral people, contaminated by Jewish, Gypsy or other blood” [

5]. Indeed, this type of discourse and practice has become such a normalized part of dehumanization that, although we might be horrified by the Nazis use of the word

disinfection to describe their state’s genocidal practices, by the 1990s we were able, without irony or horror, to use

ethnic cleansing as a common descriptor of similar practices in the former Yugoslavia, among others [

5].

At Michener, this type of dehumanization was built into the fortress-like construction of the facility itself as an isolated complex of buildings situated on the outskirts of the small town of Red Deer, where children deemed defective were hived off from normate society, often into their deep adulthood, sometimes for their entire lives. Indeed, the entire purpose of such institutions can be seen as a reflection of this desire to remove bodies seen as dangerous or polluting from the main social body, in what can be characterized as a form of passive eugenics. It is also in keeping with these values that the operations of the Michener institution and the Alberta Eugenics Board intertwined in more active eugenic ways. Alberta, the province in which Michener Center was situated, instituted an involuntary sterilization programme under the Alberta Sterilization Act that operated between 1928 and 1972, sterilizing almost 3,000 people, most of them deemed to be mental defectives. During the years of the Act, the Superintendent of Michener Center was a standing member of the Eugenics Board, Board meetings were held quarterly on the Michener campus, and many Michener inmates were involuntarily sterilized [

13,

20,

21] through the Board’s routinized eugenic practices.

In part, the disproportionate number of Michener inmates amongst Alberta’s eugenic survivors is due to a legislative act of dehumanization. When the Sterilization Act was first implemented, its operations were limited to people who volunteered for sterilization. Unsurprisingly this voluntary program saw little enthusiasm from members of the public seeking its services. As a result, an amendment to the act was produced in 1937, in which individuals who were assessed with an IQ score below 70 (the categorical cut-off typically used to identify mental defect and to categorize people as, literally, morons) were deemed to be

incapable of providing consent, and hence, could be eugenically processed without their knowledge or agreement [

22]. In effect, by declaring these people intellectually and legally non-human, they were rendered fodder for the eugenic machine.

On a more mundane level, issues of pollution, hygiene and embodiment played out within the institutional walls on a quotidian basis. Donna Bogdan, who was institutionalized between the ages of 21 to 28, was able to describe compellingly her first experiences of showering upon admission at Michener:

They said I was going to Red Deer, and I was going to Training School, and I thought, oh, that’s fantastic. I’m going to really learn something going to school. Well I got quite a big surprise! As soon as I was admitted in, they stripped us and we had to take some showers. They sprayed some stuff onto us…something to get rid of bugs, to get rid of lice…so we were sprayed with some stuff and we were all stripped naked and they gave us a bath. I wasn’t too happy with what they did, but I guess that’s what they did to everybody.

In this description we can link the cleansing of the newly-admitted inmate to the initiation of the dehumanizing process, to stigmatization, and even to eugenic discourses about cleansing the ‘healthy’ social body of undesirable stock. We can see in this room and its practices how cleanliness, othering, and dehumanization were interwoven in the institution. Most obviously, because the showers were public and given in groups, it is clear that privacy and modesty were not seen as important, perhaps not even relevant, to inmates’ bodies. The impersonal roughness attached to being stripped down, sprayed off, and cleaned up in a public setting not only shows a distinct disdain for the individual’s dignity, but is indeed a degradation ritual, a hallmark of total institutions and of depersonalization. Degradation rituals in institutions are designed to usher in personality change; in total institutions such rituals operate to symbolically erase the person who existed prior to admission, opening the way for a new identity as inmate or prisoner to be constructed in that old person’s stead [

23]. Through these means, the inductee learns that the things that a person typically can expect in terms of social niceties and human interactions cannot be counted upon by that individual any longer; in the institution their rights to a full identity and human dignity are forfeit [

23]. Additionally, the routine delousing that Donna experienced on admission reflects eugenic discourses about pollution and cleansing, indicating that staff presumed that these individuals, perhaps because of their disabilities, family backgrounds, ethnic categories or socioeconomic status, were naturally unclean, and would thus require disinfection before entering institutional life.

6. Conclusions

All four aspects of dehumanization—the naturalization of abject/otherness amongst inmates, the routinized justification of neglect and abuse against them, the use of space to distance and categorize them, and the rationale for culling undesirable/polluted bodies from the body social—were threaded throughout every aspect of daily institutional life at Michener, occurring along axes of space and its use, privacy and personal property, human emotions and personal hygiene. Life in the institution was made impersonal to a level that seems not only thoughtless but intentionally cruel and dehumanizing. Inmates, regardless of their age or disability, were treated terribly. They were not given choices in their clothing, their food preferences, their sleeping arrangements, or their access to personal objects. They were collectively herded around, often naked, in spaces such as showers and toilets, denied freedom of movement, and denied any arena for freedom of emotional expression. There were kept in locked rooms and wards, and were kept at a distance not only from material comforts, but from comfort in the form of human interaction with staff. Violence and neglect formed the fabric of their daily lives. As such, they were treated, and perhaps came to see themselves, as abject Others with few rights and fewer expectations.

As can be imagined, the enduring dehumanization that these people experienced during their tenure at Michener has had lifelong consequences for these survivors, particularly for those who were interred in early childhood. Since leaving the institution they have, literally, had to learn how to do everything that is normatively human, from making decisions about what to eat and wear, to knowing how to trust and relate to other human beings. It is clear that devastating dehumanization occurred for residents who were stripped systematically of the rights to personal space, possessions, and feelings. As occurred in many institutions, these restrictions in turn had profound effects on inmates’ abilities, both within and upon leaving the institution, to develop relationships, to engage in personal development, to understand appropriate boundaries, to make choices and accept responsibilities—in short, how to live as human beings in the world [

24]. The effects of this institutionalization have been profound and long-lasting, and we can speculate that for some, these effects have been insurmountable.

However, the effects were also profound for those who worked in the institution. The three ex-workers interviewed for this project each spoke about entering into human services work and how their experiences at Michener informed their practice. In particular, Evelyn noted that her lifelong engagement in disability advocacy has been “a life of atonement” for what she had to do while working in the institution.

However, many employees at Michener found the work tolerable enough to spend many years doing institutional work, enjoying long-term, well-paid careers that were otherwise not readily available to them in their small town [

14]. Ironically, the effects of tolerating this kind of daily, routinized dehumanization seem to have left some of these workers with less of their own humanity. Some insight into these effects can be intimated from a newspaper article published during the period when Michener was seeing its ranks reduced as a result of deinstitutionalization and normalization [

25]. The article includes an interview with a staff member who explained that the lack of doors and curtains and the public washings, toiletings and feedings were necessary because of “lack of space, resident safety and staff convenience”, reflecting a wholesale acceptance that human and embodied rights were to be properly subordinated to institutional routines and worker efficiency. The article goes on to quote John Runge, a social worker at Michener, who argued that improving the living spaces of these inmates would be a waste of funds and energy, saying instead, “Use the money for the people where it’s going to do the most good. There are a number of them [inmates] that you might as well be talking to a chicken” [

25].

In this quote we can discern several intertwined discourses about humanity and human worth. Recall that the institutions arose in part because of the needs of capital in early industrialization and urbanization, and the capacity of disciplines like education and psychology to identify and segregate the non-productive and potentially non-productive from the ‘rest of us’. Further recall that, once the hope of educating individuals with intellectual disabilities into productivity had faltered as a social and educational experiment, the warehousing of these people began to make calculable sense to reformers. These ideas about the lack of entitlement that is due to non-producers is echoed and sustained in Mr. Runge's comments. In this framing, the apportioning of resources is simply a form of modern rationality in action; of course there is no point in wasting resources on those who will not repay the investment. This is modern capitalism taken to its logical, if horrifying, conclusion.

Finally, in this quote we are able to see how someone who has worked in a place that treats people in the ways that animals are typically treated in modern, western societies, can readily make the transition to thinking that some people actually

are animals

8, barely worth the money spent to keep things at an abusive level, let alone worthy of improved conditions. We can also see how such exposure can erode one’s sense of human decency and leave one diminished. In Runge’s comments we are able to understand just how effective dehumanization is and what the long-term damages of it can be, not only for inmates but for all who engage in the embodied daily work of accomplishing it.