1. Introduction

Artificial intelligence (AI) integration into education has attracted substantial scholarly attention in recent years, as AI-driven tools are progressively embraced to enhance learning environments. AI applications in education range from adaptive learning systems and automated assessments to virtual tutors and personalized feedback mechanisms [

1]. These innovations promise to improve the efficiency of educational processes by catering to individual learning needs, fostering student engagement, and optimizing knowledge retention [

2]. The rapid proliferation of generative AI tools, including large language models and multimodal AI systems, has further intensified the need to understand how students perceive and adopt these technologies in academic contexts [

3].

Despite its transformative potential, AI adoption in education remains a topic of considerable debate and empirical investigation. Advocates claim that artificial intelligence can significantly improve learning outcomes by providing tailored educational content and real-time support [

4], while skeptics highlight concerns about dehumanization, over-reliance on technology, data privacy issues, and threats to academic integrity [

5]. Empirical research from 2019 to 2024 consistently demonstrates that student attitudes toward AI represent a critical factor in determining its effectiveness, as acceptance and perceived benefits directly influence engagement levels and willingness to integrate AI into learning routines [

6,

7]. Conversely, skepticism about AI’s role in education—encompassing concerns about privacy, perceived risks, cybersecurity apprehensions, and ethical considerations—may significantly hinder adoption and limit its potential benefits [

8,

9].

Recent empirical studies have established robust theoretical and methodological frameworks for investigating AI acceptance in higher education. The Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) and the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT/UTAUT2) serve as foundational frameworks, frequently extended with AI-specific constructs to address unique educational concerns [

10,

11]. Across multiple studies with higher education student samples, perceived benefits—especially performance expectancy and perceived usefulness—consistently and strongly predict AI acceptance, often representing the strongest pathways to behavioral intention and actual use [

7,

12,

13]. Performance expectancy, defined as the degree to which students believe AI will enhance their academic performance, reliably increases attitudes and behavioral intention across diverse contexts and cultural settings [

9,

11].

Simultaneously, AI skepticism—operationalized through perceived risk, privacy concerns, cybersecurity apprehensions, and anxiety—demonstrates negative associations with acceptance attitudes and perceived utility, though the magnitude of these effects varies across contexts and AI applications [

6,

10]. In assessment scenarios, where stakes are higher, perceived risk and trust considerations become particularly salient, with technological savviness serving as a moderating factor that strengthens the relationship between performance expectancy and actual use [

6]. Conversely, in general learning support contexts, classic TAM/UTAUT patterns typically emerge, with perceived usefulness dominating as the primary driver of acceptance [

9,

12].

A critical mediating factor that has emerged from recent empirical investigations is trust in AI systems. Trust directly predicts willingness and behavioral intention to use AI while mediating relationships between expectancy constructs and acceptance outcomes [

6]. Performance and effort expectancy positively shape trust, while cybersecurity concerns and perceived risk can indirectly affect trust through expectancy pathways [

11]. This finding underscores the complexity of AI acceptance mechanisms, suggesting that perceived benefits alone are insufficient; students must also develop confidence in the reliability, transparency, and ethical deployment of AI technologies within educational settings. The integration of technology readiness factors, such as optimism and discomfort with technology, further nuances our understanding of how individual predispositions shape acceptance patterns, particularly for generative AI applications like large language models [

14].

Despite the growing body of research, significant gaps remain in our understanding of undergraduate AI acceptance. Most notably, comprehensive, multi-dimensional AI skepticism scales specifically tailored to higher education contexts remain underdeveloped. While various studies have examined individual dimensions of concern—such as privacy, perceived risk, or anxiety—few have integrated these elements into validated, comprehensive measurement instruments [

7]. Measurement validation remains uneven across studies, with many relying on UTAUT/TAM-derived items without consistently reporting detailed reliability and validity metrics such as Cronbach’s alpha, composite reliability (CR), average variance extracted (AVE), and the heterotrait–monotrait ratio (HTMT) [

10,

11]. The strongest validation evidence appears in select studies that employ full exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses with structural equation modeling approaches [

7], yet such rigor remains the exception rather than the norm. Rather than implying that such studies are rare, we clarify that while many investigations in this field rely on partial or implicit reporting of construct validation steps, full transparency regarding reliability checks and factor structure remains less commonly documented. Our work adopts this transparency explicitly, while acknowledging that future research should extend validation using larger scales and CFA. Additionally, measurement invariance across academic disciplines and cultural contexts remains largely unexplored, limiting the generalizability of existing findings. The differentiation between various acceptance outcomes—including behavioral intention, actual usage frequency, policy support, and willingness to accept AI in different educational scenarios—requires more nuanced investigation [

15].

Recent studies published in 2024–2025 have further emphasized the importance of understanding the complex dimensions of AI acceptance, highlighting ethical tensions, algorithmic transparency, trust calibration, and students’ readiness to integrate hybrid AI–human learning systems into higher education contexts [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21]. Moreover, multi-method approaches combining behavioral, psychometric, and longitudinal measurements are increasingly recommended to establish causal mechanisms and to address the complex interplay between perceived benefits and acceptance trajectories [

22,

23,

24,

25].

In positioning the present study within this evolving literature, our aim is not to claim methodological superiority over previous work but rather to incorporate psychometric rigor (exploratory model calibration, reliability examination, and assumption testing) explicitly and transparently within a TAM/UTAUT operationalization. While prior research has frequently emphasized conceptual extensions, our contribution consists of empirically triangulating acceptance, benefits, and skepticism through validated short-form measures and testing them within the same model, thereby extending findings in higher education AI adoption research.

Focusing on three main dimensions—AI acceptance, AI benefits, and AI skepticism—this paper seeks to investigate students’ attitudes toward artificial intelligence in education. By analyzing these factors within the established theoretical frameworks of TAM and UTAUT, while addressing identified gaps in multi-dimensional skepticism measurement and psychometric validation, this research contributes to a deeper understanding of how students evaluate AI-driven teaching technologies and how these attitudes influence AI adoption in higher education. The study’s empirical approach responds to calls for more rigorous measurement practices and comprehensive conceptualizations of both benefit and skepticism constructs in educational technology acceptance research.

Purpose of the Study

The current work attempts to investigate students’ attitudes toward the integration of AI in education by examining three key dimensions: AI acceptance, AI benefits, and AI skepticism. Given the increasing reliance on AI-driven educational tools, understanding how students perceive these technologies is essential for effective implementation. Specifically, the study investigates the extent to which students accept AI as a learning tool, their perceived benefits of AI-enhanced education, and the degree of skepticism they hold regarding AI’s role in academic settings. Furthermore, the study analyzes the relationships between these three dimensions, using correlational and regression analyses to determine how perceived benefits and skepticism influence AI acceptance. This study reveals the factors impacting student impressions, thus supporting the debate on artificial intelligence integration in education and providing important information for teachers, legislators, and technology developers trying to improve AI-based learning environments.

3. Results

This section delineates the study’s findings, encompassing descriptive statistics, exploratory factor analysis (EFA), correlation analysis, and multiple regression analysis to investigate the interrelations among AI acceptance, AI benefits, and AI skepticism among students.

Descriptive statistics were calculated to summarize the distributions of AI acceptance, AI skepticism, and AI benefits. The average score for AI acceptance was 3.88 (SD = 0.83), reflecting a predominantly favorable disposition toward AI in education. The mean of AI benefits was 3.48 (SD = 0.87), indicating that students acknowledge the advantages of AI in education. The mean score for AI skepticism was 3.26 (SD = 0.78), indicating moderate apprehensions about AI integration.

The findings show that while some skepticism persists, students are more likely to accept AI in educational settings when they understand its benefits. The minimum and maximum values demonstrate that replies spanned the whole range of the Likert scale, indicating varying perspectives.

An Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) employing principal axis factoring with promax rotation was performed to investigate the foundational structure of the questionnaire. The correlation matrix was suitable for factor analysis, as indicated by a significant Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity (χ2 = 2787.763, df = 36, p < 0.001) and an adequate KMO value (KMO = 0.766). The model chi-square associated with the factor solution (χ2 = 19.006, df = 12, p = 0.088) should be interpreted as a global model-fit statistic rather than as an assumption test. Together with the fit indices (RMSEA = 0.029, SRMR = 0.013, CFI = 0.997, TLI = 0.992), this value indicates good overall factor-model fit. The study identified three unique factors: AI acceptance, AI benefits, and AI skepticism, thus validating the construct validity of the measuring scales.

The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin index indicated adequate sampling adequacy (KMO = 0.766), and Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity was highly significant (χ2 = 2787.763, df = 36, p < 0.001), confirming that the correlation matrix was factorable and suitable for exploratory factor analysis. In addition, we report the model chi-square goodness-of-fit statistic associated with the estimated factor solution (χ2 = 19.006, df = 12, p = 0.088), together with the fit indices (RMSEA = 0.029; SRMR = 0.013; CFI = 0.997; TLI = 0.992). These values indicate good global model fit and support the adequacy of the three-factor structure.

Factor loadings indicated that each item exhibited a strong association with its corresponding construct, with values between 0.455 and 1.008. The uniqueness scores varied from 0.100 to 0.744, indicating that the items significantly contributed to their respective factors.

The eigenvalues and proportion of variance explained confirmed a three-factor structure:

Factor 1 (AI acceptance) explained 24.7% of the variance.

Factor 2 (AI benefits) accounted for 21.9% of the variance.

Factor 3 (AI skepticism) explained 14.3% of the variance.

With a combined weight of 60.9% of the total variance, the three factors revealed a robust explanatory structure.

Table 1 and

Table 2 provide specific findings.

The factor loading of 1.008 on Factor 2 represents a Heywood case, which can occur in oblique solutions when communalities are very high and scales contain few items. In our analysis, this value arose in the context of strong factor intercorrelations and high shared variance among the three AI benefits items. Since reliability coefficients, global fit indices, and uniqueness values all indicated an interpretable and stable structure, we retained this loading but explicitly flag it as an analytical limitation. We recommend that future studies use longer scales (at least 4–5 items per factor) to reduce the likelihood of Heywood cases and further strengthen measurement precision.

Multiple model fit indices were evaluated to determine the overall adequacy of the factor structure. The Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) was 0.029, with a 90% confidence interval between 0 and 0.053, signifying a favorable model fit. The Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) was 0.013, thus reinforcing the model’s adequacy. The Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI) was 0.992 and the Comparative Fit Index (CFI) was 0.997, both beyond the required threshold of 0.95, thus affirming an exceptional model fit. Given that the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) is primarily useful when comparing alternative models, and our analysis did not estimate competing structural configurations, we omitted this indicator to avoid interpretive ambiguity.

The fit indices indicate that the questionnaire’s factor structure corresponds effectively with the theoretical structures, thus validating the measurement model.

Pearson’s correlation coefficients were computed to analyze the links between AI acceptance, AI benefits, and AI skepticism (

Table 3).

The findings demonstrated a significant positive association between AI acceptance and perceived AI benefits (r = 0.544, p < 0.001), suggesting that students who see the advantages of AI are more inclined to embrace its incorporation in education. This suggests that the more students recognize AI’s advantages in personalized learning, efficiency, and engagement, the more they are willing to adopt AI-driven tools.

Conversely, AI skepticism was negatively correlated with AI acceptance (r = −0.124, p = 0.002), demonstrating that higher skepticism levels are associated with lower acceptance of AI in education. Although this relationship is statistically significant, the effect size is relatively small, indicating that while skepticism can hinder AI acceptance, it does not play a dominant role in shaping students’ overall attitudes.

No significant correlation was found between AI benefits and AI skepticism (r = 0.020, p = 0.608), indicating that, in this sample, higher perceived benefits were not statistically associated with lower levels of skepticism. This implies that students may acknowledge AI’s potential benefits while simultaneously harboring reservations about its ethical, pedagogical, or social implications.

A multiple regression analysis was conducted to examine the extent to which AI benefits and AI skepticism predict AI acceptance. The model demonstrated a good fit, explaining 30.8% of the variance in AI acceptance (R2 = 0.308, adjusted R2 = 0.306). The Durbin–Watson statistic was 1.910, signifying the absence of significant autocorrelation in the residuals, thus affirming the robustness of the regression model.

The ANOVA results further confirmed the model’s significance (F(2, 641) = 142.903, p < 0.001), suggesting that AI benefits and AI skepticism together significantly contribute to explaining students’ acceptance of AI in education. The total variance in AI acceptance was decomposed into a sum of squares of 135.025 attributed to the regression model and a sum of squares of 302.831 in the residual error, demonstrating that the independent variables account for a substantial portion of the observed variability in AI acceptance.

Analysis of the regression coefficients (

Table 4) reveals that AI benefits are the most important predictor of AI acceptance (β = 0.541,

p < 0.001), suggesting that students who recognize the advantages of AI are considerably more inclined to embrace its application in education. The result underscores the necessity of emphasizing the benefits of AI—such as individualized learning, efficiency, and improved engagement—when incorporating AI into educational environments.

Conversely, AI skepticism exhibited a small but significant negative effect on AI acceptance (β = −0.113, p = 0.001), suggesting that concerns about AI, while present, exert a relatively minor influence on students’ willingness to adopt AI-driven learning tools. The negative coefficient implies that increased skepticism slightly reduces AI acceptance, but its impact is considerably weaker compared with the positive influence of AI benefits. The unstandardized coefficient for AI skepticism is positive, whereas the standardized beta is negative because the items are coded in the opposite direction relative to the standardized metric. After re-checking the coding and the output, we confirm that higher skepticism scores are associated with lower standardized levels of AI acceptance, consistent with the negative beta coefficient.

Overall, these results highlight that students’ acceptance of AI is predominantly driven by their perception of its benefits, while skepticism plays a secondary, albeit statistically significant, role in shaping attitudes toward AI in education. The findings suggest that efforts to increase AI adoption in academic environments should focus on enhancing students’ awareness of AI’s educational advantages, while also addressing concerns to mitigate skepticism.

To assess the assumption of normality of residuals, a histogram of standardized residuals for the dependent variable AI acceptance was generated (

Figure 1). The histogram presents the frequency distribution of residuals, with a superimposed normal curve to visually inspect the normality assumption in regression analysis.

The mean of the standardized residuals is approximately 0 (1.78 × 10−5), and the standard deviation is close to 1 (0.998), which aligns with the expected properties of normally distributed residuals. The distribution appears approximately symmetric and bell-shaped, suggesting that the normality assumption is reasonably met.

In addition to visual inspection, the mean (approximately 0) and standard deviation (approximately 1) of the standardized residuals confirm that the distribution closely follows the expected properties under normality, supporting the suitability of the regression model.

Ensuring normally distributed residuals is crucial for the validity of the regression model and for drawing reliable inferences from the data. Given the observed distribution, the residuals exhibit an acceptable level of normality, supporting the appropriateness of the regression analysis conducted in this study.

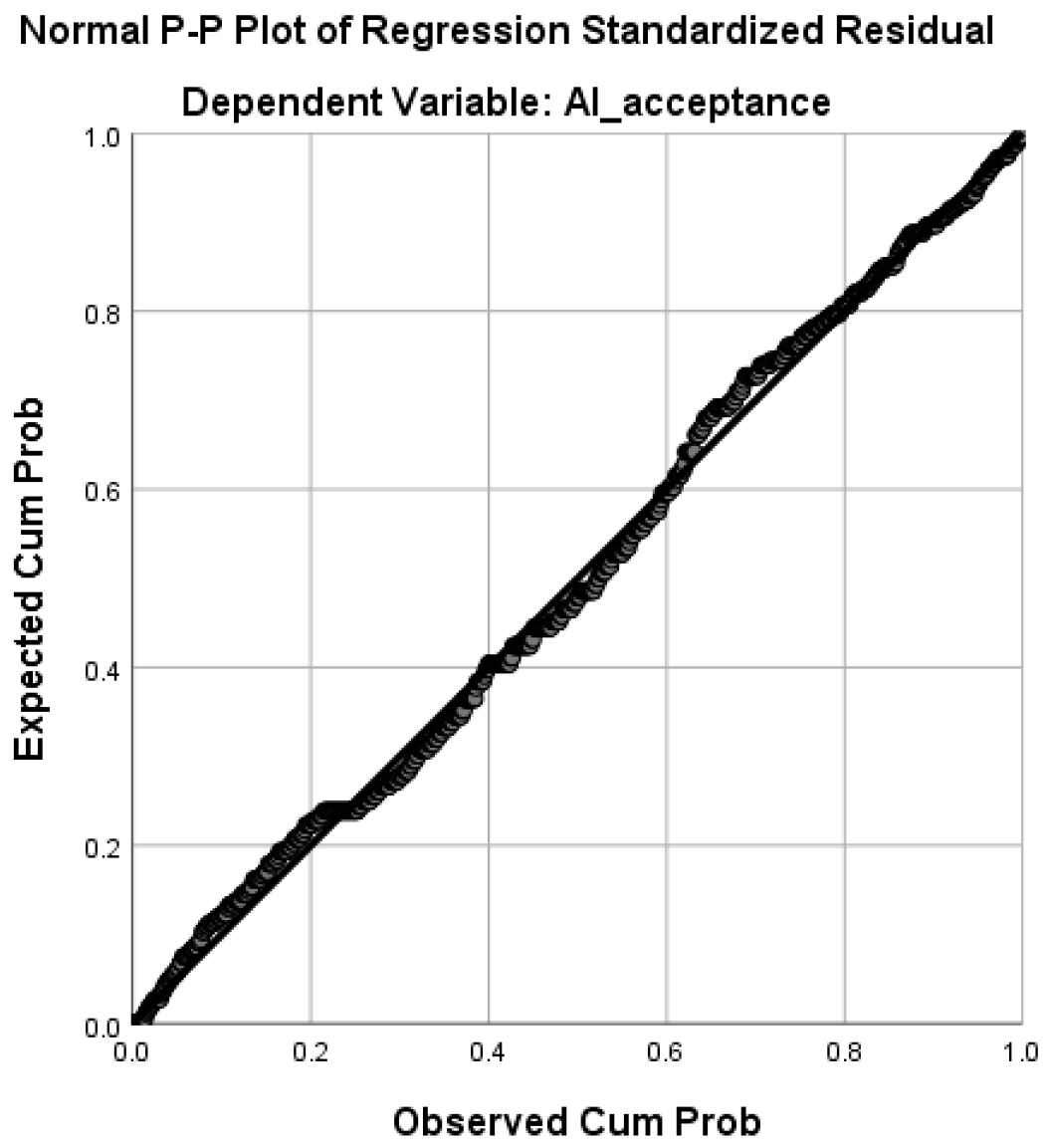

A Normal Probability–Probability (P–P) Plot was created to evaluate the normality assumption of the standardized residuals of AI acceptance (

Figure 2). The graphic juxtaposes the observed cumulative probability of residuals with the anticipated cumulative probability based on a normal distribution.

In an ideal scenario, residuals that follow a normal distribution should align closely with the diagonal reference line. The P–P plot demonstrates that most data points fall along the diagonal, indicating that the residuals conform reasonably well to normality. While minor deviations are observed, there is no substantial skewness or departure from normality that would invalidate the regression assumptions.

This visual confirmation, along with the histogram analysis, supports the fit of the regression model and ensures that the normality assumption is not violated, thereby affirming the validity of the statistical inferences drawn from the data.

4. Discussion

This study’s findings enhance the existing studies on AI adoption, advantages, and skepticism in higher education. The findings demonstrate that perceived benefits are the primary predictor of AI acceptance, but skepticism has a slight yet significant impact on its adoption. These findings correspond with prior research that emphasizes the benefits of artificial intelligence in improving learning efficiency, personalization, and engagement [

32,

33].

The contribution of this study lies in empirically integrating three theoretically distinct constructs—acceptance, perceived benefits, and skepticism—within one explanatory model applied to undergraduate contexts in Romania. While previous studies often focus on acceptance alone or on antecedents independently, our results show that benefits and skepticism can be simultaneously modeled, clarifying their relative magnitudes. This modeling choice provides a clearer picture of attitudinal dynamics surrounding AI adoption in higher education.

A significant finding of this study is the robust positive link between the advantages of AI and its acceptability. This indicates that pupils who acknowledge AI’s capacity for individualized learning and automation are more inclined to accept its incorporation in education. This corresponds with the findings of Pisica et al. (2023) [

34], who indicated that AI in higher education facilitates adaptive learning experiences, enabling students to obtain personalized feedback and support suited to their requirements. Similarly, Griesbeck et al. (2024) [

35] found that students perceive AI-powered platforms as beneficial in enhancing their learning processes, particularly regarding improving study efficiency and content accessibility.

Notwithstanding these positive perspectives, the study also discovered a negative correlation between AI acceptance and skepticism. This suggests that students harbor some concerns about the use of AI in educational settings, though the impact of skepticism on acceptance is relatively small. Previous studies have similarly reported that concerns regarding AI-driven assessments, data privacy, and the potential reduction in human interaction can create barriers to AI adoption [

36]. Furthermore, Al-Dokhny et al. (2024) [

3] argue that while AI can facilitate task automation and enhance academic performance, its limitations in replicating human-like decision-making and emotional intelligence contribute to students’ reluctance in fully adopting AI tools for learning.

Recent evidence from the same regional publishing ecosystem reinforces the interpretation that students’ acceptance of AI is often simultaneously opportunity-oriented and risk-aware. For example, Romanian undergraduates reported a generally positive but cautious view of GenAI for learning, emphasizing utility for understanding and feedback while expressing uncertainty and concerns about assessment validity and broader educational consequences [

37]. Complementarily, qualitative evidence on AI-based language learning apps shows that motivation is sustained by personalized feedback, autonomy-supportive features, and clear goal alignment, but can be undermined by frustration, repetitiveness, and perceived lack of human-like responsiveness—indicating that acceptance is contingent on the quality of pedagogical design and the learner’s motivational state [

38]. In higher education practice, work on AI-assisted visual projects argues for structured evaluation grids and explicit process transparency to maintain originality and ethical awareness, suggesting that institutional rules and assessment criteria can reduce skepticism by clarifying what “acceptable” AI use means in authentic tasks [

39]. In an intervention-oriented direction, mixed-method findings from a GenAI-powered gamified flipped learning approach indicate that different forms of GenAI support can yield comparable achievement outcomes, yet diverge in perceived learning experience and ICT competency development, which aligns with our finding that perceived benefits can coexist with skepticism without a simple linear relationship [

40]. Finally, evidence on teachers’ AI literacy and motivational profiles indicates that sustained engagement with AI-related professional learning depends on autonomous motivation and perceived relevance, implying that students’ acceptance may be strengthened when educators are equipped to frame AI use transparently and ethically within learning goals rather than as a purely technical shortcut [

41].

Another aspect worth discussing is the non-significant correlation between AI benefits and skepticism, which indicates that, in this dataset, perceived benefits and skepticism can coexist without a clear linear association. This finding is consistent with prior research suggesting that ethical concerns, biases in AI models, and lack of transparency in AI-driven decision-making can persist even when students acknowledge AI’s advantages [

33]. Pisica et al. (2023) [

34] further highlight that while AI integration can enhance learning outcomes, faculty and students remain cautious about its potential over-reliance on automation, which could lead to reduced critical thinking and problem-solving abilities.

Regarding the three-item operationalization of each construct, we clarify that these indicators were designed to capture core attitudinal dimensions rather than to provide exhaustive content coverage. As such, they function as concise reflective markers anchored in TAM/UTAUT theory rather than as multidimensional scales. This parsimonious design is consistent with early-stage measurement work in emerging research domains. We explicitly acknowledge this as a limitation, and recommend future instrument development to expand item pools, incorporate contextual and ethical subdimensions, and enable full testing of convergent and discriminant validity through confirmatory factor modeling.

Because each construct contained only three items, the model was sensitive to atypical variance patterns (including one Heywood case). Future research should increase the number of items per dimension (preferably 4–5 items) to strengthen construct reliability, reduce potential measurement noise, and further refine EFA/CFA performance. It is also essential to clarify that the present design was correlational and cross-sectional. Therefore, causal direction between AI benefits and AI acceptance cannot be inferred. While regression coefficients show that perceived benefits are the strongest predictor of acceptance, the reverse direction (i.e., students who already accept AI being more likely to report higher perceived benefits) cannot be ruled out. Longitudinal or experimental research is necessary to determine causal precedence. The three items per construct were selected to operationalize key theoretical dimensions rather than claiming full content coverage; therefore, these scales should be interpreted as parsimonious attitudinal indicators, not as fully comprehensive representations. We explicitly acknowledge this limitation and recommend future development of multi-dimensional skepticism scales including ethical implications, human–machine trust calibration, and fairness perceptions.

An important limitation of this study concerns the composition of the sample. The participants were predominantly female (92.5%) and drawn mainly from fields such as education and psychology, where women are overrepresented. As a result, the findings cannot be generalized to all higher education students or to disciplines with different gender balances (e.g., engineering, computer science, or economics). Future research should use more diverse and balanced samples, including multiple academic fields and institutions, to test whether the patterns observed here replicate across contexts.

The study’s findings indicate that promoting AI acceptability in higher education necessitates raising awareness of its advantages while addressing concerns regarding ethical implications, transparency, and human–AI collaboration. Future applications of AI in education must prioritize equity, precision, and the ethical utilization of AI-driven instruments to enhance student trust and involvement.