Unemployment Factors Among Venezuelan Immigrants in Colombia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background

2.1. Immigrant Economic Incorporation: Theoretical and Empirical Scholarship in Europe and U.S.

2.2. Unemployment and Informality of Venezuela Migrants in Columbia

3. Data and Methods

3.1. Study Variables

3.2. Data Analysis

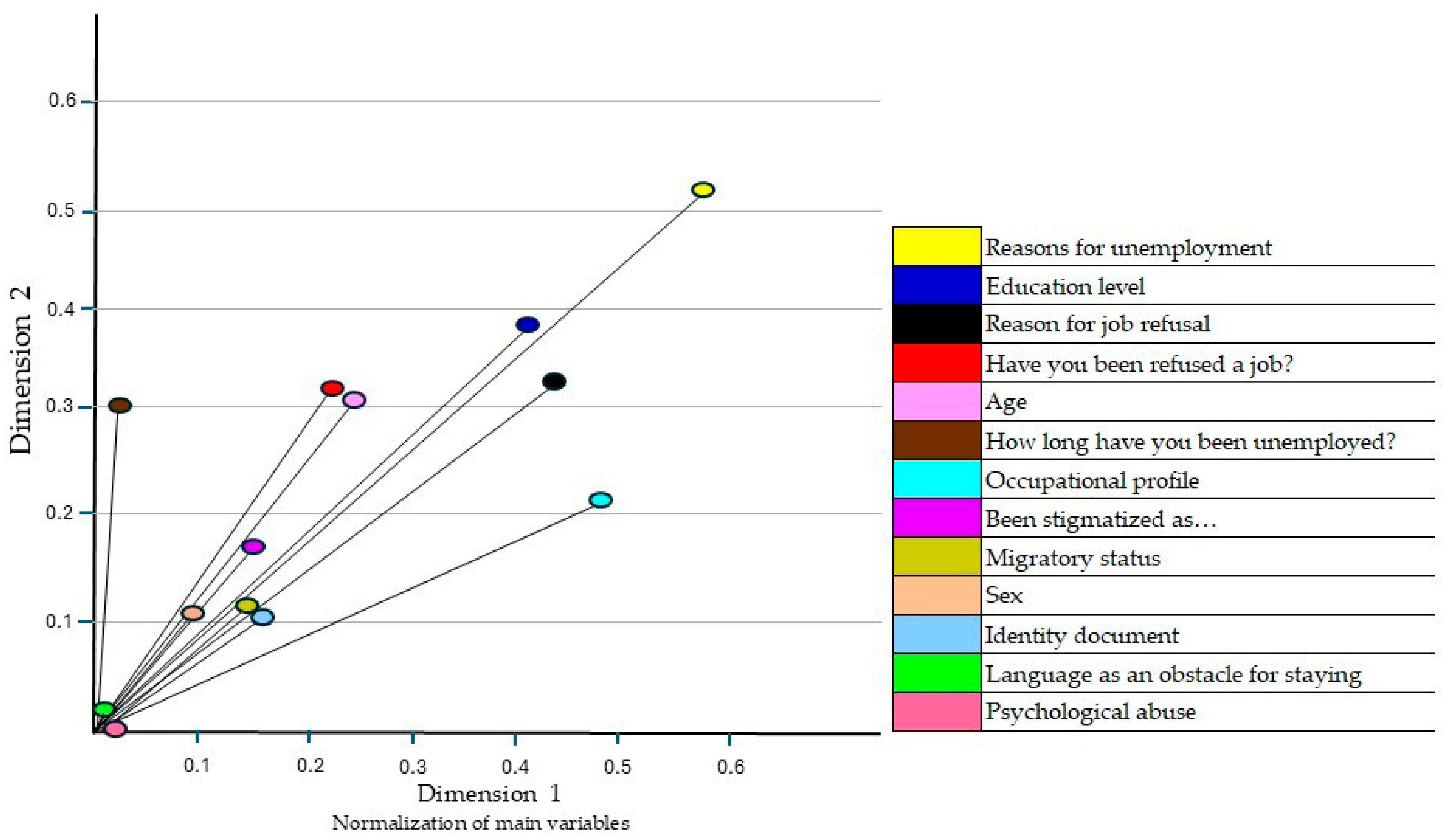

Multiple Correspondence Analysis

4. Results

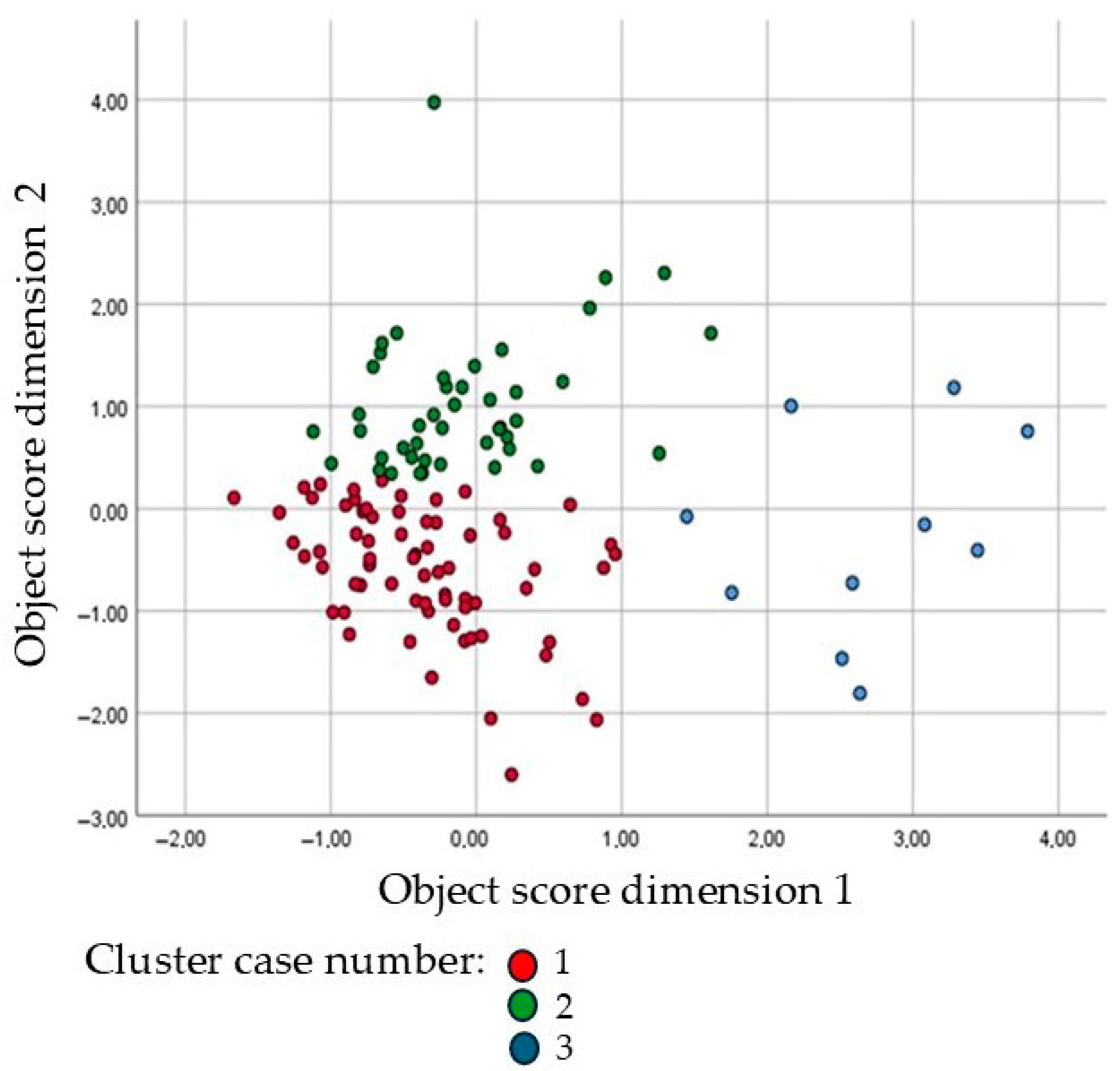

Cluster Analysis

5. Discussion

5.1. Characterisation of the Profiles of Unemployed Venezuelan Migrants

5.1.1. Profile 1

5.1.2. Profile 2

5.1.3. Profile 3

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Burzyński, M.; Deuster, C.; Docquier, F.; De Melo, J. Climate change, inequality, and human migration. J. Eur. Econ. Assoc. 2022, 20, 1145–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OIT. Estimaciones Mundiales de la OIT Sobre Los Trabajadores y Las Trabajadoras Migrantes. Resultados y Metodología, 3rd ed.; OIT: Geneva, Italy, 2021; Available online: https://www.fairrecruitmenthub.org/es/resources/estimaciones-mundiales-de-la-OIT-sobre-los-trabajadores-y-las-trabajadoras-migrantes (accessed on 8 December 2024).

- Herrera, G.; Nyberg, N. Migraciones internacionales en América Latina: Miradas críticas a la producción de un campo de conocimientos. Iconos 2017, 58, 11–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez Pizarro, J.; Cano Christiny, M.V.; Soffia Contrucci, M. Tendencias y patrones de la migración latinoamericana y caribeña hacia 2010 y desafíos para una agenda regional. Santiago de Chile: Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe (CEPAL). Poblac. Y Desarro. 2014, 109, 7–70. Available online: https://www.cepal.org/es/publicaciones/37218-tendencias-patrones-la-migracion-latinoamericana-caribena-2010-desafios-agenda (accessed on 12 December 2024).

- CIDH. Personas Refugiadas y Migrantes Provenientes de Venezuela. Comisión Interamericana de Derechos Humanos; Comisión Interamericana de Derechos Humanos (CIDH): Washington, DC, USA, 2023; [Documento OAS 217/23 del 20 de Julio 2023; Available online: https://www.oas.org/es/cidh/informes/pdfs/2023/informe-migrantesVenezuela.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Koechlin, J.; Vega, E.; Solórzano, X. Migración Venezolana al Perú: Proyectos Migratorios y Repuesta del Estado. In El Éxodo venezolano: Entre el exilio y la emigración; Koechlin, J., Eguren, J., Eds.; Lima, Peru, 2018; pp. 47–96. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=6746865 (accessed on 5 July 2025).

- United Nations-UN. Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees. 1951. Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/convention-relating-status-refugees (accessed on 18 August 2025).

- United Nations-UN. Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees. 1967. Available online: https://www.refworld.org/legal/agreements/unga/1967/en/41400 (accessed on 18 August 2025).

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees-UNHCR. Cartagena Declaration on Refugees, Colloquium on the International Protection of Refugees in Central America, Mexico and Panama Adopted by the Colloquium on the International Protection of Refugees in Central America, Mexico and Panama, held at Cartagena, Colombia from 19–22 November 1984. United Nations. Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/about-us/background/45dc19084/cartagena-declaration-refugees-adopted-colloquium-international-protection.html (accessed on 18 August 2025).

- Alto Comisionado de las Naciones Unidas para los Refugiados–ACNUR. Tendencias Globales. Desplazamiento Forzado en 2019; ACNUR: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2019; Available online: https://www.acnur.org/stats/globaltrends/5eeaf5664/tendencias-globales-de-desplazamiento-forzado-en-2019.html (accessed on 19 September 2024).

- R4V. Refugiados y Migrantes de Venezuela. Actualización de la Plataforma de Coordinación Interagencial para Refugiados y Migrantes. 2024. Available online: https://www.r4v.info/es/refugiadosymigrantes (accessed on 11 November 2024).

- Migración Colombia. Radiografía de venezolanos en Colombia. Informe Especial. 2017. Available online: https://unidad-administrativa-especial-migracion-colombia.micolombiadigital.gov.co/infografias-migracion-colombia/infografias-2017 (accessed on 28 October 2024).

- Mondelli, J.I. Instrumentos Regionales sobre Refugiados y temas relacionados. La fuerza vinculante de la definición regional de la Declaración de Cartagena sobre Refugiados (1984). 2018. Available online: https://www.refworld.org.es/docid/5d03d0b54.html (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- Martine, G.; Hakkert, R.; Guzmán, J.M. Aspectos Sociales de la Migración Internacional: Consideraciones Preliminares. Notas Poblac. 2001, 28, 163–193. Available online: https://repositorio.cepal.org/3c6466e9-7 (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Cabieses, B.; Gálvez, P.; Ajraz, N. Migración internacional y salud: El aporte de las teorías sociales migratorias a las decisiones en salud pública. Rev. Peru. Med. Exp. Y Salud Pública 2018, 35, 285–291. Available online: https://rpmesp.ins.gob.pe/index.php/rpmesp/article/view/3102 (accessed on 15 August 2025). [CrossRef]

- Fassio, C.; Kalantaryan, S.; Venturini, A. Foreign Human Capital and Total Factor Productivity: A Sectoral Approach. Rev. Income Wealth 2019, 66, 613–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzi, M.; Kahanec, M.; Kureková, L.M. How Immigration Grease is Affected by Economic, Institutional, and Policy Contexts: Evidence from EU Labor Markets. Kyklos 2018, 71, 213–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. Migration from Venezuela to Colombia: Short- and Medium-Term Impact and Response Strategy 1–208. Colombia. 2018. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10986/30651 (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- DANE. Caracterización de los migrantes y retornados desde Venezuela a partir del CNPV-2018. Informes de Estadística Sociodemográfica Aplicada N° 5. 2021. Available online: https://www.dane.gov.co/files/investigaciones/poblacion/informes-estadisticas-sociodemograficas/2021-10-01-caracterizacion-migrantes-y-retornados-desde-venezuela-CNPV.2018.pdf (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- DANE. La información del DANE en la toma de decisiones regionales. Área Metropolitana de Cúcuta. 2022. Sistema Estadístico Nacional (SEN). Available online: https://www.dane.gov.co/index.php/estadisticas-por-tema/informacion-regional/informacion-estadistica-desagregada-con-enfoque-territorial-y-diferencial/informacion-del-dane-para-la-toma-de-decisiones-en-departamentos-y-ciudades-capitales?highlight=WyJpbmZsYWNpb24iLCJpbmZsYWNpXHUwMGYzbiIsImRpY2llbWJyZSIsMjAyMV0= (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Massey, D.S.; Arango, J.; Hugo, G.; Kouaouci, A.; Pellegrino, A.; Taylor, J.E. Theories of International Migration: A Review and Appraisal. Popul. Dev. Rev. 1993, 13, 431–466. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2938462 (accessed on 18 December 2024). [CrossRef]

- Bonacich, E. ‘Advanced Capitalism and Race Relations in the United States: A Divided Interpretation of the Labour Market’. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1976, 41, 34–51. Available online: https://www.scilit.com/publications/04b94228bd662d0fb0f97fa7d9d0815c (accessed on 16 June 2024).

- Clark, K.; Garratt, L.; Li, Y.; Lymperopoulou, K.; Shankley, W. Local deprivation and the labour market integration of new migrants to England. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2019, 45, 3260–3282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piore, M. Birds of Passage: Migrant Labor and Industrial Societies; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piore, M. Dualism in the Labor Market: A Response to Uncertainty and Flux: The Case of France. Rev. Écon. 1978, 29, 26–48. Available online: https://www.persee.fr/doc/reco_0035 (accessed on 14 December 2024). [CrossRef]

- Hudson, K. The new labor market segmentation: Labor market dualism in the new economy. Soc. Sci. Res. 2007, 36, 286–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCollum, D.; Findlay, A. ‘Flexible’ workers for ‘flexible’ jobs? The labour market function of A8 migrant labour in the UK. Work Employ. Soc. 2015, 29, 427–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonacich, E. ‘A Theory of Ethnic Antagonism: The Divided Labour Market’. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1972, 37, 547–559. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2093450 (accessed on 19 October 2024). [CrossRef]

- Boswell, T. A Divided Interpretation of the Labour Market Discrimination Against Chinese Immigrants, 1850–1882. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1986, 51, 352–371. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2095307 (accessed on 25 October 2024). [CrossRef]

- Hirschman, C.; Wong, M. The Extraordinary Educational Attainment of Asian-Americans: A Search for Historical Evidence and Explanations. Soc. Forces 1986, 65, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portes, A.; Rumbaut, R. Immigrant America: A Portrait, 3rd ed.; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2006; Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/j.ctt1pq07x (accessed on 12 August 2025).

- Portes, A. Migración y cambio social: Algunas reflexiones conceptuales. RES 2009, 12, 9–37. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=3753768 (accessed on 6 December 2024).

- Beine, M.; Docquier, F.; Rapoport, H. Brain Drain and Human Capital Formation in Developing Countries: Winners and Losers. Econ. J. 2008, 118, 631–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herranz, Y. Inmigración e incorporación laboral. Migr. Publ. Del Inst. Univ. De Estud. Sobre Migr. 2016, 8, 127–163. Available online: https://revistas.comillas.edu/index.php/revistamigraciones/article/view/4414 (accessed on 6 November 2024).

- Zhang, H.; Nardon, L.; Sears, G.J. Migrant workers in precarious employment. Equal. Divers. Incl. 2022, 41, 254–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borjas, G. Heaven’s Door: Immigration Policy and the American Economy; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2001; Available online: https://press.princeton.edu/books/paperback/9780691088969/heavens-door (accessed on 17 October 2024).

- Bauder, H. Labor Movement: How Migration Regulates Labor Markets; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cranston, S. Expatriate as a ‘Good’ Migrant: Thinking Through Skilled International Migrant Categories. Popul. Place Space 2017, 23, 2058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winterheller, J.; Hirt, C. Career patterns of young highly skilled migrants from Southeast Europe in Austria: Investigating accumulation and use of career capital. Pers. Rev. 2017, 46, 222–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Rica, S.; Glitz, A.; Ortega, F. Immigration in Europe: Trends, Policies, and Empirical Evidence. In Handbook of the Economics of International Migration; Chiswick, B.R., Miller, P.W., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 1303–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasinitz, P.; Mollenkopf, J.H.; Waters, M.C.; Holdaway, J. Inheriting the City: The Children of Immigrants Come of Age; Russell Sage Foundation: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2008; Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7758/9781610446556 (accessed on 28 August 2025).

- Solé, C. Discriminación Racial en el Mercado de Trabajo; Consejo Económico y Social: Madrid, Spain, 1995; Available online: http://bibliotecaced.uab.cat/cgi-bin/koha/opac-detail.pl?biblionumber=6061&shelfbrowse_itemnumber=6004 (accessed on 22 October 2024).

- Becker, G. The Economics of Discrimination, 2nd ed.; Chicago University Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1971; Available online: https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/E/bo22415931.html (accessed on 24 August 2024).

- Arrow, K. The Theory of Discrimination. In Discrimination in Labor Markets; Ashenfelter, O., Rees, A., Eds.; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1973; pp. 3–33. Available online: https://dataspace.princeton.edu/handle/88435/dsp014t64gn18f. (accessed on 18 October 2024).

- Vernby, K.; Dancygier, R. Can immigrants counteract employer discrimination? A field factorial experiment reveals the immutability of ethnic hierarchies. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0218044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar-Idáñez, M. Discriminaciones múltiples de los migrantes en perspectiva de derechos. In BARATARIA Revista Castellano-Manchega de Ciencias Sociales; Asociación Castellano Manchega de Sociología: Tolodo, Spain, 2014; pp. 39–54. Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=322132552003 (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- Doeringer, P.; Piore, M. Mercados Internos de Trabajo y Análisis Laboral. Madrid: Ministerio de Trabajo y Seguridad Social; Ministerio de Empleo y Seguridad Social: Madrid, Spain, 1985; Available online: https://libreriavirtual.trabajo.gob.es/libreriavirtual/detalle/ETR0003 (accessed on 15 October 2024).

- Guzi, M.; Kahanec, M.; Kureková, L.M. The impact of immigration and integration policies on immigrant-native labour market hierarchies. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2023, 49, 4169–4187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kangasniemi, M.; Mas, M.; Robinson, C.; Serrano, L. The economic impact of migration: Productivity analysis for Spain and the UK. J. Product. Anal. 2012, 38, 333–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, S. Borders in the age of mobility. In Human Security and Migration in Europe’s Southern Borders; Ferreira, S., Ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: Lisbon, Portugal, 2019; pp. 51–66. Available online: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-319-77947-8_4 (accessed on 9 September 2024).

- Benedetti, A.; Salizzi, E. Llegar, pasar, regresar a la frontera. Aproximación al sistema de movilidad argentino-boliviano. Transp. Y Territ. 2011, 4, 148–179. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=3674908 (accessed on 6 November 2024).

- Abel, G.J.; Sander, N. Quantifying Global International Migration Flows. Science 2014, 343, 1520–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiddian-Qasmiyeh, E.; Daley, P. Introduction. Conceptualising the Global South and South-South Encounters; Routledge Online Handbooks: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawyn, S.J. New directions for research on migration in the Global South. Int. J. Sociol. 2016, 46, 163–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawley, H.; Teye, J.K. South–South migration and inequality: An introduction. In The Palgrave Handbook of South–South Migration and Inequality; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanyoro, K. Rethinking Power and Reciprocity in the “Field”. In The Palgrave Handbook of South–South Migration and Inequality; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 105–123. Available online: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-031-39814-8_6 (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- Carella, F. The Governance of South–South Migration: Same or Different? In The Palgrave Handbook of South–South Migration and Inequality; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 587–607. Available online: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-031-39814-8_27 (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- Mazza, J.; Forero, V.N. Perú and Migration from Venezuela: From Early Adjustment to Policy Misalignment. In The Palgrave Handbook of South–South Migration and Inequality; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 653–678. Available online: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-031-39814-8_30 (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- Nawyn, S.J. Migration in the Global South: Exploring New Theoretical Territory. Int. J. Sociol. 2016, 46, 81–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiddian-Qasmiyeh, E. Recentering the South in Studies of Migration. Migr. Soc. 2020, 3, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acevedo, I.; Castellani, F.; Lotti, G.; Székely, M. Informality in the time of COVID-19 in Latin America: Implications and policy options. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0261277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CEPAL. Balance Preliminar de las Economías de América Latina y el Caribe 2020. Informe Anual de la Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe; CEPAL: Santiago, Chile, 2021; Available online: https://www.cepal.org/es/publicaciones/46501-balance-preliminar-economias-america-latina-caribe-2020 (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- Alvarez, J.; Pizzinelli, C. COVID-19 and the Informality-Driven Recovery: The Case of Colombia’s Labor Market; International Monetary Fund: Washington, DC, USA, 2021; Available online: https://www.elibrary.imf.org/view/journals/001/2021/235/article-A001-en.xml (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- Bertelsmann Stiftung. Annual Report 2024; Bertelsmann Stiftung: Gütersloh, Germany, 2025; Available online: https://www.bertelsmann-stiftung.de/en/publications/publication/did/bertelsmann-stiftung-jahresbericht-2024 (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- Galvis Molano, D.L.; Sarmiento Espinel, J.A.; Silva Arias, A.C. Perfil laboral de los migrantes venezolanos en Colombia-2019. Encuentros 2020, 18, 116–127. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=7772901 (accessed on 18 October 2024).

- Mutis, O.O.M.; Rios, I.C.J.; Montaño, G.L.M.; Monroy, R.V. Crisis u oportunidad: Impacto de la migración venezolana en la productividad colombiana. Rev. Desarro. Y Soc. 2021, 81, 13–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitácora Migratoria. Observatorio de Venezuela. Reporte N° 24; Universidad del Rosario: Bogota, Colombia, 2024; Available online: https://urosario.edu.co/sites/default/files/2024-04/reporte-abril-de-bitacora-migratoria-2024.pdf (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- DANE. Boletín Técnico: Ocupación Informal. Trimestre Enero-Marzo 2024. 10 de mayo de 2024. Departamento Administrativo Nacional de Estadísticas. Available online: https://www.dane.gov.co/files/operaciones/GEIH/bol-GEIHEISS-ene2024-mar2024.pdf (accessed on 23 November 2024).

- Mora García, E.M. El trabajo informal y la calidad de vida: Paradigma en la frontera colombo venezolana. Línea Imaginaria 2022, 13, 279–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erazo, K. Cúcuta, la Ciudad Atrapada en la Violencia y la Extorsión Masiva. Reseña publicada en el portal de la Fundación Paz & Reconciliación, 2023, 21 de abril de 2023. Available online: https://www.pares.com.co/cucuta-la-ciudad-atrapada-en-la-violencia-y-la-extorsion-masiva/ (accessed on 21 June 2025).

- OIM. Diagnóstico Socioeconómico y Migratorio de Cúcuta (2020–2023); Fondo de la OIM para el Desarrollo: Bogota, Colombia, 2023; Available online: https://repository.iom.int/bitstream/handle/20.500.11788/2409/4.%20C%C3%BAcuta_Diagn%C3%B3stico%20Socioecn%C3%B3mico.pdf.pdf?sequence=15&isAllowed=y (accessed on 17 June 2025).

- Taborda Burgo, J.C.; Acosta Ortiz, A.M.; Garcia, M.C. Discriminación en silencio: Percepciones de migrantes venezolanos sobre la discriminación en Colombia. Desarro. Y Soc. 2021, 89, 143–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ossa Rubio, S.L. Vulnerabilidad y pobreza en tránsito: Un caso de representación visual de la migración venezolana en Colombia. Papel Político 2022, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, A.; Peters, M.E.; Zhou, Y.-Y. Left Out: How Political Ideology Affects Support for Migrants in Colombia. J. Politics 2024, 86, 1291–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OIT. Mujeres Refugiadas y Migrantes de Venezuela en Colombia: ¿Quiénes Son y Que Barreras Enfrentan Para su Integración Socioeconómica? Resumen Ejecutivo; Organización Internacional del Trabajo–IOT: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024; Available online: https://www.ilo.org/es/publications/mujeres-refugiadas-y-migrantes-de-venezuela-en-colombia (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Sánchez Calderón, B.J.; Munevar Avila, L.A. Inclusión Laboral para la población migrante proveniente de Venezuela en Colombia: Sistematización del piloto para la identificación y mitigación de barreras de acceso al mercado laboral del servicio público de empleo, 2019; Estudio del Banco Interamericano de Desarrollo en conjunto con la OIT y la Unidad del Servicio de Empleo: Bogotá, Colombia, 2020; Available online: https://www.ilo.org/sites/default/files/wcmsp5/groups/public/%40americas/%40ro-lima/documents/publication/wcms_759357.pdf (accessed on 21 June 2025).

- Felbo-Kolding, J.; Leschke, J. Wage Differences between Polish and Romanian Intra-EU Migrants in a Flexi-Secure Labour Market: An Over-Time Perspective. Work Employ. Soc. 2023, 37, 877–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albornoz Arias, N.; Cuberos, M.A.; Ramirez Martinez, C.; Santafe, A. Situation and perceptions of Venezuelan migrants settled in Cúcuta, La Parada and Los Patios de Norte de Santander, Colombia. 2025. UNISIMON, Barranquilla, Colombia, V1, UNF:6:XtEFFf68IMbw5b1ZFE1+sQ== [fileUNF]. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, J. Fertility, migration, and maternal wages: Evidence from Brazil. J. Hum. Cap. 2016, 10, 377–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhavan, S.; Schatz, E.; Clark, S.; Collinson, M. Child mobility, maternal status, and household composition in rural South Africa. Demography 2012, 49, 699–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schieckoff, B.; Sprengholz, M. The labor market integration of immigrant women in Europe: Context, theory, and evidence. SN Soc. Sci. 2021, 1, 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntioudis, D.; Masa, P.; Karakostas, A.; Meditskis, G.; Vrochidis, S.; Kompatsiaris, I. Ontology-Based Personalized Job Recommendation Framework for Migrants and Refugees. Big Data Cogn. Comput. 2022, 6, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, B.; Munevar, L. Inclusión laboral para la población migrante proveniente de Venezuela en Colombia. Sistematización del piloto para la identificación y mitigación de barreras de acceso al mercado laboral del servicio público de empleo 2019; Inter-American Development Bank and the International Labour Organization: Bogotá, Colombia, 2020; Available online: https://www.ilo.org/es/publications/inclusion-laboral-para-la-poblacion-migrante-proveniente-de-venezuela-en (accessed on 19 August 2024).

- DANE. Estadísticas por tema. Departamento Administrativo Nacional de Estadística Colombia. 2019. Available online: https://www.dane.gov.co/index.php/estadisticas-por-tema (accessed on 22 August 2024).

- Muñoz-Mora, J.C.; Aparicio, S.; Mrtinez-Moya, D.; Urbano, D. From immigrants to local entrepreneurs: Understanding the effects of migration on entrepreneurship in a highly informal country. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2022, 28, 78–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanek, M.; Veira, A. Ethnic nichingin a segmented labour market: Evidence from Spain. Migr. Lett. 2012, 9, 249–262. Available online: https://www.ceeol.com/search/article-detail?id=480921 (accessed on 13 November 2024). [CrossRef]

- Bowser, D.M.; Agarwal-Harding, P.; Sombrio, A.G.; Shepard, D.S.; Harker, A. Integrating Venezuelan Migrants into the Colombian Health System During COVID-19. Health Syst. Reform. 2022, 8, 2079448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrench, J.; Modood, T. The Effectiveness of Employment Equality Policies in Relation to Immigrants and Ethnic Minorities in the UK; International Labour Office Geneva: Geneva, Switzerland, 2000. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/sites/default/files/wcmsp5/groups/public/@ed_protect/@protrav/@migrant/documents/publication/wcms_201869.pdf (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- Zanoni, W.; Díaz, L. Discrimination against migrants and its determinants: Evidence from a Multi-Purpose Field Experiment in the Housing Rental Market. J. Dev. Econ. 2024, 167, 103227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neckerman, K.M.; Kirschenman, J. Hiring strategies, racial bias, and inner-city workers. Soc. Probl. 1991, 38, 433–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, P.; Tilly, C. Stories Employers Tell: Race, Skill, and Hiring in America; Russell Sage Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 2021; Available online: https://books.google.com.co/books?hl=es&lr=&id=_gOGAwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PR7&dq=Stories+employers+tell:+Race,+skill,+and+hiring+in+America&ots=jeCzeZdNOu&sig=mY1MdIJoGIdvV5DNsddYGPmKlyk&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=Stories%20employers%20tell%3A%20Race%2C%20skill%2C%20and%20hiring%20in%20America&f=false (accessed on 30 July 2025).

| Variable | Code | Category | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 122 | 100.0% | ||

| Age | 1 | 18–29 years old | 47 | 38.5% |

| 2 | 30–35 years old | 21 | 17.2% | |

| 3 | 36–47 years old | 34 | 27.9% | |

| 4 | 48–61 years old | 10 | 8.2% | |

| 6 | More than 61 years | 10 | 8.2% | |

| Sex | 1 | Male | 25 | 20.5% |

| 2 | Female | 97 | 79.5% | |

| Education Level | 3 | None | 1 | 0.8% |

| 4 | Incomplete primary school | 12 | 9.8% | |

| 5 | Completed primary school | 5 | 4.1% | |

| 6 | Did not complete secondary school | 35 | 28.7% | |

| 7 | Completed secondary school | 48 | 39.3% | |

| 8 | Graduate | 0 | 0.0% | |

| 9 | Completed primary school | 5 | 4.1% | |

| 10 | Advanced Technical University | 5 | 4.1% | |

| 11 | University | 11 | 9.0% | |

| Occupational profile | 1 | Farmer and skilled agricultural, forestry and fishing worker | 0 | 0.0% |

| 2 | Director and manager | 2 | 1.6% | |

| 3 | (*) Essential occupations | 16 | 13.1% | |

| 4 | Officer, operator and craftsman of mechanical arts and other trades | 6 | 4.9% | |

| 6 | Installation and assembly machine operator | 1 | 0.8% | |

| 7 | Administrative support staff | 2 | 1.6% | |

| 8 | Scientific and intellectual professional | 3 | 2.5% | |

| 9 | Mid-level technician professional | 8 | 6.6% | |

| 10 | Service worker | 31 | 25.4% | |

| 11 | Sex worker | 1 | 0.8% | |

| 12 | Retail and trade seller | 52 | 42.6% | |

| (**) Current immigration status? | 1 | Irregular | 29 | 23.8% |

| 2 | Regular with permission | 76 | 62.3% | |

| 3 | Regular migrant with visa | 0 | 0.0% | |

| 4 | Regular refugee | 5 | 4.1% | |

| 6 | Regular resident | 12 | 9.8% | |

| Does an identity document support your regular immigration status? | 1 | Certification of Single Registry of Venezuelan Migrants in Colombia (RUMV). Temporary Protection Permit | 55 | 59.1% |

| 2 | Identification document issued by the host country | 16 | 17.2% | |

| 3 | Neither | 8 | 8.6% | |

| 4 | Other | 9 | 9.7% | |

| 6 | Expired passport | 4 | 4.3% | |

| 7 | Valid passport | 1 | 1.1% | |

| How long have you been unemployed? | 1 | 0–3 months | 38 | 31.1% |

| 2 | 10–12 months | 12 | 9.8% | |

| 3 | 4–6 months | 20 | 16.4% | |

| 4 | 7–9 months | 10 | 8.2% | |

| 6 | More than 12 months | 42 | 34.4% | |

| Why are you out of work? | 1 | Native citizens of the host country are prioritised. | 23 | 19.5% |

| 2 | Because I’ve been sick since I arrived. | 10 | 8.5% | |

| 3 | Because of my irregular status (no documents). | 35 | 29.7% | |

| 4 | I have no networks of friends or acquaintances to help me find a job. | 18 | 15.3% | |

| 6 | I don’t know where to get information about job vacancies. | 10 | 8.5% | |

| 7 | No work is available since the pandemic began. | 26 | 22.0% | |

| 8 | Others | 13 | 11.0% | |

| Have you ever been denied a job? | 1 | No | 26 | 21.3% |

| 2 | Yes | 96 | 78.7% | |

| (***) Believes he/she was denied the job due to | 1 | Being a migrant or foreigner | 51 | 53.7% |

| 2 | Age | 29 | 30.5% | |

| 3 | Sex (being a man or being a woman), age, a lot of competition (labour supply) | 4 | 4.2% | |

| 4 | Not having experience | 12 | 12.6% | |

| 6 | Not having documents | 33 | 34.7% | |

| 7 | High level of competition (labour supply) | 18 | 18.9% | |

| 8 | Skin colour | 1 | 1.1% | |

| Have you ever felt that the language used in your current location has been an obstacle to your settlement or permanence? | 1 | Sometimes | 39 | 32,00% |

| 2 | Hardly ever | 10 | 8.2% | |

| 3 | Almost always | 3 | 2.5% | |

| 4 | Never | 70 | 57.4% | |

| (****) In the place where you currently reside, you have been reported as | 1 | Worker | 81 | 67.5% |

| 2 | Honest | 74 | 61.7% | |

| 3 | Entrepreneur | 50 | 41.7% | |

| 4 | Job creator | 2 | 1.7% | |

| 5 | None of the above | 13 | 10.8% | |

| In the place where you currently reside, have you been a victim of psychological abuse (unequal treatment with respect to nationals, insults, ridicule) by immigration officials? | 1 | Sometimes | 19 | 15.6% |

| 2 | Hardly ever | 10 | 8.2% | |

| 3 | Almost always | 5 | 4.1% | |

| 4 | Never | 86 | 70.5% | |

| 6 | Always | 2 | 1.6% |

| Dimension | Cronbach’s Alpha | Variance Accounted for | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (Eigenvalue) | Inertia * | % Variance | ||

| 1 | 0.725 | 3.027 | 0.233 | 23.332 |

| 2 | 0.711 | 2.910 | 0.224 | 22.419 |

| Total | 5.937 | 0.457 | ||

| Mean | 0.718 a | 2.968 | 0.228 | 22.159 |

| Dimension | Mean 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | ||

| Sex | 0.098 | 0.110 | 0.104 |

| Age | 0.247 | 0.313 | 0.280 |

| Education level | 0.424 | 0.381 | 0.403 |

| Occupational profile | 0.487 | 0.213 | 0.350 |

| Migratory status | 0.131 | 0.115 | 0.123 |

| Identity document | 0.142 | 0.106 | 0.124 |

| How long have you been unemployed? | 0.088 | 0.300 | 0.194 |

| Reasons for unemployment | 0.407 | 0.330 | 0.369 |

| Have you been refused a job? | 0.224 | 0.325 | 0.274 |

| Reason for job refusal | 0.579 | 0.502 | 0.540 |

| Language as an obstacle for staying | 0.011 | 0.047 | 0.029 |

| Been stigmatized as… | 0.145 | 0.164 | 0.155 |

| Psychological abuse | 0.044 | 0.004 | 0.024 |

| Total, active 1 | 3.027 | 2.910 | 2.968 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Morffe Peraza, M.Á.; Albornoz-Arias, N.; Cuberos, M.-A.; Ramírez-Martínez, C.; Peña Echezuría, J.A. Unemployment Factors Among Venezuelan Immigrants in Colombia. Societies 2026, 16, 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc16010015

Morffe Peraza MÁ, Albornoz-Arias N, Cuberos M-A, Ramírez-Martínez C, Peña Echezuría JA. Unemployment Factors Among Venezuelan Immigrants in Colombia. Societies. 2026; 16(1):15. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc16010015

Chicago/Turabian StyleMorffe Peraza, Miguel Ángel, Neida Albornoz-Arias, María-Antonia Cuberos, Carolina Ramírez-Martínez, and José Alberto Peña Echezuría. 2026. "Unemployment Factors Among Venezuelan Immigrants in Colombia" Societies 16, no. 1: 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc16010015

APA StyleMorffe Peraza, M. Á., Albornoz-Arias, N., Cuberos, M.-A., Ramírez-Martínez, C., & Peña Echezuría, J. A. (2026). Unemployment Factors Among Venezuelan Immigrants in Colombia. Societies, 16(1), 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc16010015