Place Attachment Disruption: Emotions and Psychological Distress in Mexican Land Defenders

Abstract

1. Introduction

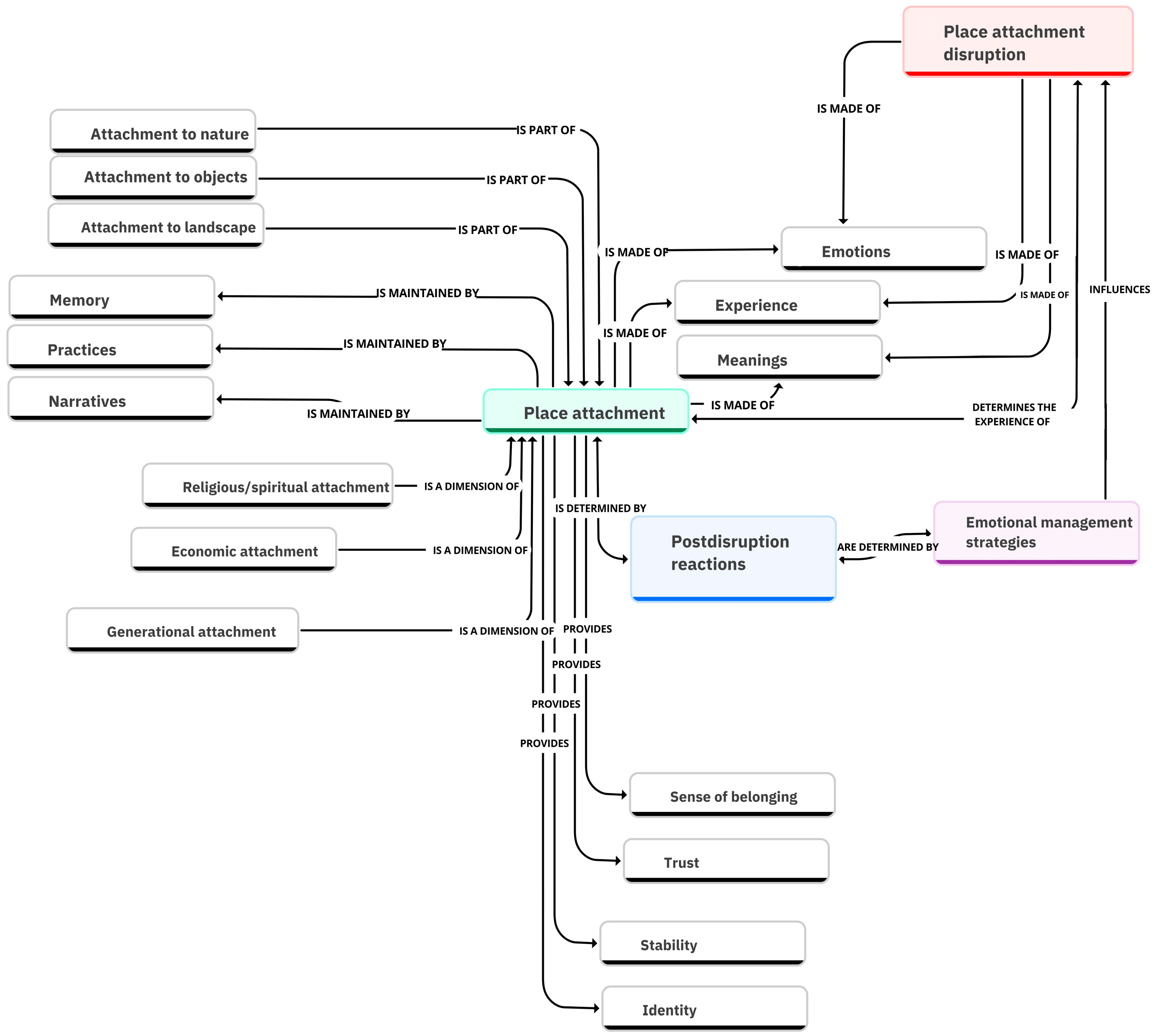

1.1. Theoretical Framework and Definitions

1.1.1. Place and Place Attachment

1.1.2. Place Attachment Disruption

1.1.3. Emotional Management

1.2. Objectives

- The emotions associated with place attachment disruption and psychological distress in land defenders.

- The relation of these emotions and land defenders’ emotional management strategies.

- The effects of emotional management strategies on psychological distress among land defenders over time.

2. Method

2.1. Study Area: El Salto and Juanacatlán

2.2. Participants

2.3. Methodological Approach: A Committed and Long-Term Perspective

2.4. Materials and Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Two Sides of One Story: Pre-Disruption and Disruption of Attachment to Place

“… I remember that the abundant one was mercury, because we used to play with it. We would grab it—you have seen how mercury looks like, right? We would grab little balls and throw them like this, and they would make a ton of little balls, and our game was to gather them up and make a little ball again, and ah… you would walk around playing like that, playing with that damn mercury”.(Pedro, age 63, personal communication, 30 September 2019)

“Since I worked for a company, they would perform maintenance every six months, around Easter and Christmas vacations. Then, I think that, back then, it was cyclical, you already knew (snaps his fingers), you would go out there in the, there in the…the damn river would turn white, they [the fish] would crowd like this in the backwaters, they would go like that, but in huge patches of hundreds of cubic and square meters”.(Pedro, age 63, personal communication, 30 September 2019)

“But… but before that, it… like it… I remember… that the… even when the river was already polluted, there was a livestock farm, as well as many animals, many trees Mmm…I remember there were so many anthills, that together-… there was a basketball court, and we would gather with our fists in our shirts the…the fine sand that they take from the anthills, the pebbles…we would gather them and make figures”.(Rosa, age 31, personal communication, 18 January 2020)

“I remember something very, very present…it was, I was already older, I tell you, I was like 19–20, there was my cousin and my uncle, one of my grandmother’s brothers, my uncle Rigo, my uncle Pepe, another of my grandmother’s brothers, my dad, my dad’s brothers, we were eating, and someone said: Do you remember when, when we went down the river and caught a fish so big, like this?. So, I asked, like… like they always took us hunting in another town, to search and so on. Why haven’t we gone there? Where is it? And then, like, in a tone that’s kind of teasing me (laughs), my dad says: Where could it be? Well… here. And I was like, Here? Where? Can you tell me where? (…) And he says: Here. Here by the river, haven’t you been to Juanacatlan? And I said, “Yes.” “The river runs through there, haven’t you seen it?” he asked me. And I was like… my cousin says that he felt like… his blood was burning and he says: “I felt like so much… anger” (…) The first thing I did was… that same day that happened, that same day, my cousin and I, we painted all the streets: “Did you know there is a river? Do you hear the river? Do you know where the river is?” We put up large signs on the walls in all the streets.(Rosa, age 31, personal communication, 18 January 2020)

Since I found out about the power plant and the gas pipeline, there hasn’t been a single day when I’ve been able to sleep peacefully. I go to sleep and dream, and I dream about the gas pipeline. I dream about the thermoelectric plant, I dream that I’m fighting, I dream that… It’s like my subconscious is constantly saying, “Bang, bang, bang, bang! You’re not doing enough.” You know? So, yes. Even my sleep time is: “bang, bang, bang, bang, bang!” Like a war, right? (Laughs) It reminds me a lot of the song by…Silvio Rodríguez, Sueño con serpientes (I Dream of Snakes), because I’m like that all the time…dreaming of a… disaster in my little head”.(Nisa, age 24, personal communication, 30 September 2019)

Field work Diary Log—5 April 2019, El SaltoVisit to Martha’s HouseContext notes: I visited Martha’s house today. She invited me to lunch to meet Laura, an academic visiting and working with the group for several years. We were having lunch with Martha and Rosa (members of the GLD), Laura, Doña Alicia (a domestic helper), a young woman assisting her, and me.“We continued eating, and the topic of insecurity in El Salto came up. The other visitor, Laura, was very interested in organized crime in the community. Doña Alicia and her helper calmly and naturally told us about some recent events, such as a shootout in Las Lilas, which they said did not appear in the newspaper, but photos of the bodies were posted in the community’s Facebook group; citizens themselves counted 16 dead. Doña Alicia’s helper showed me photos of something that had happened a week earlier: they found 10 bodies perfectly lined up on the roadside leading to the municipal center from the Chapala highway, as well as 17 bodies in the canal two weeks before. For them, this is an everyday reality [they commented with a grave expression and a following silence]”.

3.2. Disruption of Place Attachment as an Emotional Process

- (1)

- Meanings and emotions related to place attachment: nature’s fertility, source of life, enjoyment, and personal satisfaction, expressed with love, hope, and joy.

- (2)

- Meanings and emotions related to place attachment disruption: contamination, illness, death, and, therefore, pain, helplessness, fear, anger, guilt, and loss.

- (3)

- Meanings and emotions related to the actions and individual and collective reconstruction of place attachment.

“I realized that I can no longer speak about my territory because it is so devastated, so wounded, so… that it chokes me—I do not even know how to put it. It is no longer easy for me (while crying) to be on the front line because… it hurts so much (swallows and sobs) that my territory, something I love so deeply (sobs and takes a breath), is killing those I care about (…) But how to relate this?… That’s what has been difficult for me: making the connection between devastation and emotional impact. I do not know if I am making myself clear. Before, I could talk about it because I didn’t feel it as closely—I saw it in my neighbors, in someone I knew, in someone passing by—and now it is (laughs sadly) so close.”.(Rosa, age 31, personal Communication, 18 January 2020)

“How…how didn’t they tell us?” I mean, how didn’t they…I mean, like the adults, how…when they saw that they were dying, how didn’t they…? I mean, I do not know, like…I say it was so stunning, stunning, that not even they could stop it, well, I do not know.”.(Rosa, age 31, personal communication, 18 January 2020)

3.3. Post-Disruption and Reinvention of Place Attachments

“And that is why we’re defending it, and it takes a lot of work, but here we are (she mentions it with a sigh). Even though many people think we are… like we are crazy and… and that we are troublemakers, and that’s how they treat us, but we keep going anyway. That is basically what we do”.

“Inés used to be one of the most involved persons in the struggle against the thermoelectric, but she broke her arm and her son is chronically ill, so the load was too much to handle, and now she had to take distance”.(Martha, age 63, discussion group, 16 May 2023)

“Imagine not being able to… You have to dehumanise yourself in some way to enter into a process of caring for and attending to others. But we are already very weak from the effort of trying to maintain an idea of… This issue is complex. First, to be able to tie everything together with each of the people we get involved with. And then, apart from that, to have the physical, emotional, economic, and social strength to walk. And then, to walk within the collective. And then, bound together, to walk outside. And then, with that monster of disease and death, it’s like: we hold hands, and we then look at it, and look it in the eye! (She mentions this in a hurried and agitated manner, as if he were running out of air) And how do we face it? And how to associate it and explain it? And tell them “your liver is damaged by that factory”. I mean, it is really complex to be able to associate the idea with new people who did not know the territory, which is the majority. I don’t know, there are a lot of things…”.(Martha, age 63, discussion group, 16 May 2023)

Emotional Management Strategies

“My goal is, since January started, every day I go to Cerro de la Cruz (a hill) for at least an hour, take my children for a walk, to fertilize…the air, the soil. And…because we can stop for a piece of paper, but in the meantime, we are in…I tell myself…”let us plant strawberries, and we will go like this,” like getting life back, well, like…that in itself there is an imposed illness (…) it hurts me that in the last two years, people very close to me have died as if for nothing, I mean like… from one moment to the next. Without expecting it, without being sick. And that they have died like that, and like that, that fear…how I try not to paralyze myself and…and move…in the sense of…like in another sense-, maybe not…not in recovering paradise but not that, the devastation frustrates the life of my children or those around me who yes…which is very…yes…”.(Rosa, age 31, personal communication, 18 January 2020)

“Before, all of this was covered in water. This is what the state is betting on: the state is betting on oblivion. On erasing from people’s memories what used to be on their land”.(Pedro, age 63, personal communication, Participant Observation Log, 3 February 2019)

“Comrade, what are we doing wearing ourselves out here, right? We could be building” (…) half, or more than half, like three-quarters of our lives are spent fighting, fighting, and fighting, and how much time do we have left to build? How much time do we have left to say: “Well, I learned to plant in a different way, um…I learned, or I went to take care of the river, I went to take care of the forest”, no?.(Nisa, age 24, Personal communication, 30 September 2019)

“Trying to get away from civilization a little, because civilization represents something that is already very…very damaged at the moment, to get closer to the earth, to plant, or rather, like…like my belief in the spiritual (referring to an intangible, supra-human dimension related to a sense of trascendence) has been, I think, or what I have developed as a spiritual belief is: “the closer we get to and improve our relationship with nature, as human beings, eh…we will be able to get out a little bit of the barbarism in which we find ourselves”.(Pepe, age 34, personal communication, 2 October 2019)

4. Discussion

4.1. Theoretical Implications

4.2. Policy Implications

4.3. Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ripple, W.J.; Wolf, C.; Newsome, T.M.; Barnard, P.; Moomaw, W.R. World scientists’ warning of a climate emergency. BioScience 2020, 70, 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cianconi, P.; Betrò, S.; Janiri, L. The Impact of Climate Change on Mental Health: A Systematic Descriptive Review. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pihkala, P. Anxiety and the Ecological Crisis: An Analysis of Eco-Anxiety and Climate Anxiety. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballew, M.T.; Uppalapati, S.S.; Myers, T.; Carman, J.; Campbell, E.; Rosenthal, S.A.; Kotcher, J.E.; Leiserowitz, A.; Maibach, E. Climate change psychological distress is associated with increased collective climate action in the U.S. npj Clim. Action 2024, 3, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodds, J. The psychology of climate anxiety. BJPsych Bull. 2021, 45, 222–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flores, E.C.; Brown, L.J.; Kakuma, R.; Eaton, J.; Dangour, A.D. Mental health and wellbeing outcomes of climate change mitigation and adaptation strategies: A systematic review. Environ. Res. Lett. 2024, 19, 014056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, S.K.; Hogg, T.L.; Leviston, Z.; Walker, I. From anger to action: Differential impacts of eco-anxiety, eco-depression, and eco-anger on climate action and wellbeing. J. Clim. Change Health 2021, 1, 100003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.E.O.; Benoit, L.; Clayton, S.; Parnes, M.F.; Swenson, L.; Lowe, S.R. Climate change anxiety and mental health: Environmental activism as buffer. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 16708–16721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathers-Jones, J.; Todd, J. Ecological anxiety and pro-environmental behaviour: The role of attention. J. Anxiety Disord. 2023, 98, 102745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickman, C. Eco-Anxiety in Children and Young People—A Rational Response, Irreconcilable Despair, or Both? Psychoanal. Study Child 2024, 77, 356–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pihkala, P. Toward a Taxonomy of Climate Emotions. Front. Clim. 2022, 3, 738154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunsolo, A.; Ellis, N.R. Ecological grief as a mental health response to climate change-related loss. Nat. Clim. Change 2018, 8, 275–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojala, M.; Cunsolo, A.; Ogunbode, C.A.; Middleton, J. Anxiety, Worry, and Grief in a Time of Environmental and Climate Crisis: A Narrative Review. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2021, 23, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, G.; Sartore, G.M.; Connor, L.; Higginbotham, N.; Freeman, S.; Kelly, B.; Stain, H.; Tonna, A.; Pollard, G. Solastalgia: The distress caused by environmental change. Australas. Psychiatry Bull. R. Aust. New Zealand Coll. Psychiatr. 2007, 15, S95–S98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galway, L.P.; Beery, T.; Jones-Casey, K.; Tasala, K. Mapping the Solastalgia Literature: A Scoping Review Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horwitz, A.V. Distinguishing distress from disorder as psychological outcomes of stressful social arrangements. Health 2007, 11, 273–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheate, B. Climate change and mental health: The rising tide of eco-distress. Perspect. Public Health 2025, 145, 185–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, D.; Hanaček, K. A global analysis of violence against women defenders in environmental conflicts. Nat. Sustain. 2023, 6, 1045–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crandon, T.J.; Scott, J.G.; Charlson, F.J.; Thomas, H.J. A social–ecological perspective on climate anxiety in children and adolescents. Nat. Clim. Change 2022, 12, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Léger-Goodes, T.; Malboeuf-Hurtubise, C.; Trinity Mastine, T.; Généreux, M.; Paradis, P.O.; Camden, C. Eco-anxiety in children: A scoping review of the mental health impacts of the awareness of climate change. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 872544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UNEP (United Nations Environment Programme). Responding to the Needs of Environmental Defenders and Civil Society. 22 April 2020. Available online: https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/story/responding-needs-environmental-defenders-and-civil-society (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- Business and Human Rights Resource Centre. Land and Environmental Defenders. 2021. Available online: https://www.business-humanrights.org/en/big-issues/human-rights-defenders-civic-freedoms/land-environment-defenders/ (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- Glazebrook, P.; Opoku, E. Defending the Defenders: Environmental Protectors, Climate Change and Human Rights. Ethics Environ. 2018, 23, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markkula, I.; Turunen, M.; Rikkonen, T.; Rasmus, S.; Koski, V.; Welker, J.M. Climate change, cultural continuity and ecological grief: Insights from the Sámi Homeland. Ambio 2024, 53, 1203–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middleton, J.; Cunsolo, A.; Pollock, N.; Jones-Bitton, A.; Wood, M.; Shiwak, I.; Flowers, C.; Harper, S.L. Temperature and place associations with Inuit mental health in the context of climate change. Environ. Res. 2021, 198, 111166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Front Line Defenders. Global Analysis 2024/25. 2025. Available online: https://www.frontlinedefenders.org/sites/default/files/1609_fld_ga24-5_output.pdf (accessed on 28 September 2025).

- Gloss Nuñez, D.; García Chapinal, I. Environmental Knowledges in Resistance Mobilization, (Re)Production, and the Politics of Place. The Case of the Cooperativa Mujeres Ecologistas de la Huizachera, Jalisco (Mexico). In Feminism in Movement, 1st ed.; De Souza Lima, L., Otero Quezada, E., Roth, J., Eds.; Transcript Verlag: Bielefeld, Germany, 2023; pp. 261–273. Available online: https://www.transcript-open.de/isbn/6102 (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Carone, M.T.; Vennari, C.; Antronico, L. How Place Attachment in Different Landscapes Influences Resilience to Disasters: A Systematic Review. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leviston, Z.; Dandy, J.; Horwitz, P.; Drake, D. Anticipating environmental losses: Effects on place attachment and intentions to move. J. Migr. Health 2023, 7, 100152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, D.; Murphy, C.; Lorenzoni, I. Place attachment, disruption and transformative adaptation. J. Environ. Psychol. 2018, 55, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darabaneanu, D.; Maci, D.; Oprea, I.M. Influence of Environmental Perception on Place Attachment in Romanian Rural Areas. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowlby, J. Attachment and Loss, Volume 1: Attachment, 1st ed.; Hogarth Press and the Institute of Psychoanalysis: London, UK, 1969; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Low, S.M. Symbolic Ties That Bind. In Place Attachment; Altman, I., Low, S., Eds.; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1992; pp. 253–278. [Google Scholar]

- Gloss, D.M. Del Corazón a la Organización: El Apego al Lugar en Experiencias de Defensa del Territorio en Jalisco [From the Heart to the Organization: Attachment to Place in Territorial Defense Experiences in Jalisco]. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Guadalajara, Guadalajara, México, 2021. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Del+Coraz%C3%B3n+a+la+Organizaci%C3%B3n:+El+Apego+al+Lugar+en+Experiencias+de+Defensa+del+Territorio+en+Jalisco&author=Gloss,+D.M.&publication_year=2021 (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Scannell, L.; Gifford, R. Personally Relevant Climate Change: The Role of Place Attachment and Local Versus Global Message Framing in Engagement. Environ. Behav. 2013, 45, 60–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Si, W. Pro-Environmental Behavior: Examining the Role of Ecological Value Cognition, Environmental Attitude, and Place Attachment among Rural Farmers in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 17011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sýkora, J.; Horňáková, M.; Visser, K.; Bolt, G. ‘It is natural’: Sustained place attachment of long-term residents in a gentrifying Prague neighbourhood. Soc. Cult. Geogr. 2022, 24, 1941–1959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Best, K.; Carrico, A.R.; Donato, K.; Mallick, B. A multicontextual analysis of place attachment, environmental perceptions, and mobility in southwestern Bangladesh. Transl. Issues Psychol. Sci. 2022, 8, 461–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wnuk, A.; Oleksy, T. Too attached to let others in? The role of different types of place attachment in predicting intergroup attitudes in a conflict setting. J. Environ. Psychol. 2021, 75, 101615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Cai, L.; Bai, B.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, J. National forest park visitors’ connectedness to nature and pro-environmental behavior: The effects of cultural ecosystem service, place and event attachment. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2023, 42, 100621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karchegani, A.M.; Savari, M. Integrating the protection motivation model with place attachment theory to examine rural residents’ intentions toward low-carbon behaviors: Empirical evidence from Iran. Results Eng. 2025, 28, 107180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jardine, E.; Lange, E. Childhood Attunements to Nature Impact Adult Behavioral Patterns: The Importance of “Other-than-Human” Attachments. Eur. J. Ecopsychol 2024, 9, 38–73. Available online: https://lnkd.in/gjrmBxWi (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Brown, B.; Perkins, D. Disruptions in Place Attachment. In Place Attachment; Altman, I., Low, S., Eds.; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1992; pp. 279–304. [Google Scholar]

- Hochschild, A. The Managed Heart, 1st ed.; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2003; Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=The+Managed+Heart&author=Hochschild,+A.&publication_year=2003 (accessed on 4 October 2025).

- Whittier, N. Emotional Strategies: The Collective Reconstruction and Display of Oppositional Emotions in the Movement against Child Sexual Abuse. In Passionate Politics: Emotions and Social Movements, 1st ed.; Goodwin, J., Jasper, J., Polletta, F., Eds.; The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2001; pp. 233–251. [Google Scholar]

- Gravante, T.; Poma, A. Manejo emocional y acción colectiva: Las emociones en la arena de la lucha política [Emotional management and collective action: Emotions in the arena of political struggle]. Estud. Sociológicos 2018, 36, 595–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comisión Interamericana de Derechos Humanos (CIDH) [Inter-American Commission on Human Rights] Comunicado de Prensa. CIDH Otorga Medidas Cautelares a Favor de Pobladores de las Zonas Aledañas al río Santiago en México. [CIDH Grants Precautionary Measures in Favor of Residents of the Areas Surrounding the Santiago River in Mexico]. Available online: https://www.oas.org/es/cidh/prensa/comunicados/2020/028.asp#:~:text=CIDH%20otorga%20medidas%20cautelares%20a,al%20R%C3%ADo%20Santiago%20en%20M%C3%A9xico (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- Enciso, A. La Jornada. Muerte Lenta del río Santiago por Contaminación [Slow Death of the Santiago River Due to Pollution]. Available online: https://www.jornada.com.mx/2013/03/25/politica/002n1pol#:~:text=El%20r%C3%ADo%20es%20un%20%E2%80%9Cmal,Ambiente%2C%20no%20hubo%20respuesta%20positiva (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- Enciso, A. La Jornada. Ecocidio: En El Salto y Juanacatlán las Enfermedades “No Dan Tregua” a la Población: Especialista [Ecocide: In El Salto and Juanacatlán, Diseases “Give No Respite” to the Population: Specialist]. Available online: https://www.jornada.com.mx/2013/03/25/politica/003n1pol (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- Gloss, D. Emociones y estrategias de manejo emocional en la defensa del territorio de mujeres de la cuenca Lerma-Chapala-Santiago [Emotions and Strategies of Emotional Management in Land Defense of Woman of the Lerma-Chapala Basin]. In Trayectorias de los Estudios Feministas del Género: Una Antología Desde y Para América Latina [Trayectories of Gender Feminist Studies: An Anthology from and for Latin America; Sanchez, N.R., Ed.; Ibero Puebla: San Andrés Cholula, Mexico, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, D.; Malkin, E. Un Chernóbil en Cámara Lenta [A Chernobil in Slow Motion]. New York Times [Internet]. 1 January 2020. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/es/2020/01/01/espanol/america-latina/mexico-medioambiente-tmec.html (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Greenpeace. Estudio de la Contaminación en la Cuenca del Río Santiago y la Salud Pública en la Región [Study of Pollution in the Santiago River Basin and Public Health in the Region] [Internet]. 2012. Available online: http://www.greenpeace.org/mexico/global/mexico/report/2012/9/informe_toxicos_rio_santiago.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Gloss, D.M. Las formas de apropiación del espacio en la defensa del lugar: El caso de la Cooperativa Mujeres Ecologistas de la Huizachera [Forms of Space Appropriation in the Defense of Place: The Case of the Huizachera Women Ecologists Cooperative]. Master’s Thesis, ITESO, Guadalajara, México, 2015. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Las+Formas+de+Apropiaci%C3%B3n+del+Espacio+en+la+Defensa+del+Lugar:+El+caso+de+la+Cooperativa+Mujeres+Ecologistas+de+la+Huizachera&author=Gloss,+D.M.&publication_year=2015 (accessed on 4 October 2025).

- Domínguez Cortinas, G. Propuesta Metodológica Para la Implantación de Una Batería de Indicadores de Salud que Favorezcan el Establecimiento de Programas de Diagnóstico, Intervención y Vigilancia Epidemiológica en las Poblaciones Ubicadas en la Zona de Influencia del Proyecto de la Presa Arcediano en el Estado de Jalisco [Methodological Proposal for the Implementation of a Battery of Health Indicators that Favor the Establishment of Diagnostic, Intervention and Epidemiological Surveillance Programs in the Populations Located in the Area of Influence of the Arcediano dam Project in the State of Jalisco]; Universidad Autónoma de San Luis Potosí-Comisión Estatal del Agua de Jalisco: Guadalajara, México, 2011; Available online: https://transparencia.info.jalisco.gob.mx/sites/default/files/u531/INFORME%20FINAL%20ARCEDIANO_CEA_UEAS_JALISCO_2011_1%20-%20copia_opt.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Tribunal Interamericano del Agua. Caso: Deterioro y Contaminación del río Santiago. Municipios de El Salto y Juanacatlán, Estado de Jalisco, República Mexicana [Inter-American Water Tribunal. Case: Deterioration and Pollution of the Santiago River. Municipalities of El Salto and Juanacatlán, State of Jalisco, Mexican Republic]; Tribunal Interamericano del Agua: San José, Costa Rica, 2007; Available online: http://tragua.com/wpcon-tent/uploads/2012/04/caso_rio_santiago_mexico.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Un Salto de Vida. Problemática Ambiental de la Región de los Pueblos de El Salto, Juanacatlán, Puente Grande, Tolotlán y sus Comunidades en Jalisco, México [A Leap of Life (2008). Environmental Problems of the Region of the Towns of El Salto, Juanacatlán, Puente Grande, Tolotlán and Their Communities in Jalisco, Mexico]. 2020. Available online: https://cronicadesociales.files.wordpress.com/2008/08/radiografia-el-salto-1.pdf (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Palacios Rodríguez, O.A. La teoría fundamentada: Origen, supuestos y perspectivas [Grounded theory: Origin, assumptions and perspectives]. Intersticios Soc. 2021, 22, 47–70. Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=421769000003 (accessed on 4 October 2025).

- Glaser, B.G.; Strauss, A.L. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research; Aldine: Chicago, IL, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Besana, P.B. Notas sobre el uso de la etnografía y la teoría fundamentada en ciencia política. Un análisis amplio de la participación política y del Estado en asentamientos informales de la periferia de Buenos Aires, Argentina [Notes on the use of ethnography and grounded theory in political science: A broad analysis of political participation and the state in informal settlements on the periphery of Buenos Aires, Argentina]. Univ. Humanística 2018, 86, 107–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barajas, D. Rechazan Instalación de Planta Termoeléctrica en el Salto [Installation of Thermoelectric Plant in el Salto Rejected]; Milenio: Monterrey, Mexico, 2025; Available online: https://www.google.com/amp/s/amp.milenio.com/politica/comunidad/rechazan-instalacion-de-planta-termoelectrica-en-el-salto (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Devine-Wright, P. Rethinking NIMBYism: The role of place attachment and place identity in explaining place-protective action. J. Community Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 19, 426–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasper, J.M. Emotions and Social Movements: Twenty Years of Theory and Research. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2011, 37, 285–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Masso, A.; Dixon, J.; Durrheim, K. Place Attachment as Discursive Practice. In Place Attachment: Advances in Theory, Methods and Applications, 1st ed.; Manzo, L., Devine-Wright, P., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; pp. 75–86. [Google Scholar]

- Hummon, D. Community Attachment: Local sentiment and sense of place. In Place Attachment, 1st ed.; Altman, I., Low, S., Eds.; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1992; pp. 253–278. [Google Scholar]

- Cebeci, F.; Reyes, M.E.S.; Innocenti, M.; Kochuchakkalackal, G.; Jeremie, W.; Buvar, A.; Atak, I.; Karaman, M.; Dinçer, R.; Nalbantçılar, S.C.; et al. Eco-Anxiety Without Borders: A Cross-National Study on Climate Perceptions, Beliefs About Government Climate Action, and Climate Concern. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2025, 2025, 00207640251378601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boivin, M.; Gousse-Lessard, A.S.; Hamann Legris, N. Towards a unified conceptual framework of eco-anxiety: Mapping eco-anxiety through a scoping review. Cogent Ment. Health 2025, 4, 2490524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gravante, T. Forced Disappearance as a Collective Cultural Trauma in the Ayotzinapa Movement. Lat. Am. Perspect. 2020, 47, 87–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bingley, W.J.; Tran, A.; Boyd, C.P.; Gibson, K.; Kalokerinos, E.K.; Koval, P.; Kashima, Y.; McDonald, D.; Greenaway, K.H. A Multiple Needs Framework for Climate Change Anxiety Interventions. Am. Psychol. 2022, 77, 812–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabhan, G.P.; Orlando, L.; Smith Monti, L.; Aronson, J. Hands-On Ecological Restoration as a Nature-Based Health Intervention: Reciprocal Restoration for People and Ecosystems. Ecopsychology 2020, 12, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vela Sandquist, A.; Biele, L.; Ehlert, U.; Fischer, S. Is solastalgia associated with mental health problems? A scoping review. BMJ Ment. Health 2025, 28, e301639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gloss Nuñez, D.M.; Nuñez Fadda, S.M. Emotional Management Strategies and Care for Women Defenders of the Territory in Jalisco. Societies 2024, 14, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westerhof, G.J.; Keyes, C.L. Mental Illness and Mental Health: The Two Continua Model Across the Lifespan. J. Adult Dev. 2010, 17, 110–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergunst, F.; Williamson, R.; Massazza, A.; Berry, H.L.; Olff, M. A dual-continuum framework to evaluate climate change impacts on mental health. Nat. Ment. Health 2024, 2, 1318–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iasiello, M.; van Agteren, J. Mental health and/or mental illness: A scoping review of the evidence and implications of the dual-continua model of mental health. Evid. Base 2020, 1, 1–45. Available online: https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/informit.261420605378998 (accessed on 4 October 2025).

- Qiu, S.; Qiu, J. From individual resilience to collective response: Reframing ecological emotions as catalysts for holistic environmental engagement. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1363418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Hidalgo, M. The ambivalent political work of emotions in the defence of territory, life and the commons. Environ. Plan. E Nat. Space 2021, 4, 1291–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Hidalgo, M.; Zografos, C. Emotions, power, and environmental conflict: Expanding the ‘emotional turn’ in political ecology. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2020, 44, 235–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poma, A. Climate change and environmental activism: The role of attachment to the place. TLA-MELAUA Rev. Cienc. Soc. 2019, 13, 215–237. [Google Scholar]

- Leuschner, E.; Versteegen, P. The Dynamics of Emotions in Protests. Working Paper Series 2023:13. Gothenburg. QoG, Department of Political Science, University of Gothenburg. 2023. Available online: https://www.gu.se/sites/default/files/2023-10/2023_13_Leuschner_Versteegen.pdf (accessed on 4 October 2025).

- Gerber, Z. Self-compassion as a tool for sustained and effective climate activism. Integr. Environ. Assess. Manag. 2023, 19, 7–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, W.J.; Hine, D.W. Self-compassion, physical health, and health behaviour: A meta-analysis. Health Psychol. Rev. 2021, 15, 113–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yip, V.T.; Tong, M.W.E. Self-compassion and attention: Self-compassion facilitates disengagement from negative stimuli. J. Posit. Psychol. 2021, 16, 593–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, S.; Massazza, A.; Akhter-Khan, S.C.; Wray, B.; Husain, M.I.; Lawrance, E.L. Mental health and psychosocial interventions in the context of climate change: A scoping review. npj Ment. Health Res. 2024, 3, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojala, M. How do children cope with global climate change? Coping strategies, engagement, and well-being. J. Environ. Psychol. 2012, 32, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventriglio, A.; Bellomo, A.; di Gioia, I.; Di Sabatino, D.; Favale, D.; De Berardis, D.; Cianconi, P. Environmental Pollution and Mental Health: A Narrative Review of Literature. CNS Spectr. 2020, 26, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marczak, M.; Wierzba, M.; Zaremba, D.; Kulesza, M.; JSzczypiński, J.; Bartosz Kossowski, B.; Magdalena Budziszewska, M.; Jarosław, M.; Michałowski, J.M.; Christian, A.; et al. Beyond climate anxiety: Development and validation of the inventory of climate emotions (ICE): A measure of multiple emotions experienced in relation to climate change. Glob. Environ. Change 2023, 83, 102764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Surname | Age | Years as Part of the Group | Interview Date and Place | Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pedro | 63 | 16 | September 30th, 2019 El Salto | Narrative |

| Martha | 59 | 16 | September 30th, 2019 El Salto | Narrative |

| Nisa | 24 | 3 Participates in three groups | September 30th, 2019 Juanacatlán | Narrative |

| Pepe | 34 | 6 Participates in two groups | October 2nd, 2019 Juanacatlán | Narrative |

| Rosa | 31 | 15 Participates in two groups | January 18, 2020 El Salto | Narrative |

| Raco | 30 | 7 Participates in two groups | January 18, 2020 El Salto | Narrative |

| 10 Members of the Group of land defenders | 24–60 | 3–16 years Includes participants of the three groups | January 18, 2020 El Salto | Discussion group |

| Sabina | 41 | 10 Participates in two groups | May 15, 2023 El Salto | Narrative |

| 7 Members of the Group of land defenders (Martha, Nisa, Marina, Rubi, Pedro, Jorge, Oscar) | 30–64 | 6–19 years Includes participants of the three groups | May 16, 2023 El Salto | Discussion group |

Exploratory Interview Guide

|

| Frst Collective History Discussion Group Guide 2005–2007 Emergence and influences: How GLD was envisioned, shaped by political experiences, literature, ideology, and music. Identity and purpose: Why create GLD instead of joining existing organizations, and what GLD represented at that time. 2007–2012 Strategic changes: Shifts in objectives or strategies due to context and conditions. Collective vs. movement: Active participants and the relationship between GLD and the broader movement. 2012–2013 Distance and participation: Brief overview of the situation, members’ roles, and participation from afar. Impact of distance: What distance represented, new influences, and GLD’s identity at that moment. 2013–2018 Strategic evolution: Possible changes in objectives or strategies shaped by context. Active participation and identity: Who was involved and what GLD represented during this stage. 2018–2020 Strategic adjustments: Shifts in objectives or strategies due to conditions and context. Collective identity: Active participants and GLD’s meaning at that time. |

Community Involvement and Practices

|

| Conceptual Level | Categories |

|---|---|

| First Conceptual Level: Place attachment and defense of place |

|

| Second Conceptual Level: Emotions |

|

| Third Conceptual Level: Emotions in collective action |

|

| Surname | Age | Love | Pride | Anger/Rage | Pain | Trust (in Community) | Trust | Fear (of Violence, Premature Death and/or Disease) | Sadness | Solitude | Guilt | Nostalgia |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pedro | 63 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||

| Martha | 59 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Rosa | 31 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||

| Nisa | 24 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||

| Raco | 30 | x | x | x | ||||||||

| Sabina | 41 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||

| Pepe | 34 | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||

| Rubi | 30 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Marina | 63 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Disruption Phase | Emotions | Related Categories |

|---|---|---|

| Place attachment Pre-disruption | Love | Memory Community Identity Sense of stability Psychological wellbeing |

| Pride | ||

| Trust | ||

| Place attachment disruption | Moral shock, feeling overwhelmed | Psychological distress Dominant emotions |

| Powerlessness, Helplessness | ||

| Hopelessness | ||

| Worry, Constant Fear of premature death, fear of illness | ||

| Defeat, frustration | ||

| Guilt | ||

| Treason (loss of trust) | ||

| Anger, rage, resentment | ||

| Disappointment, disillusionment | ||

| Sadness, Pain, sorrow | ||

| Nostalgia- homesickness | ||

| Astonishment, feeling overwhelmed, stunned | ||

| Post-disruption: attachment reconstruction emotional management strategies: Activism/ struggle Solidarity Care and support Restorative actions with land Contact with nature Family connections Community involvement and connection | Love | Emotional management strategies Emotions of resistance Psychological wellbeing Psychological distress |

| Trust | ||

| Empathy | ||

| Strength | ||

| Solidarity | ||

| Hope | ||

| Courage, bravery |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Nuñez Fadda, S.M.; Gloss Nuñez, D.M. Place Attachment Disruption: Emotions and Psychological Distress in Mexican Land Defenders. Societies 2026, 16, 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc16010014

Nuñez Fadda SM, Gloss Nuñez DM. Place Attachment Disruption: Emotions and Psychological Distress in Mexican Land Defenders. Societies. 2026; 16(1):14. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc16010014

Chicago/Turabian StyleNuñez Fadda, Silvana Mabel, and Daniela Mabel Gloss Nuñez. 2026. "Place Attachment Disruption: Emotions and Psychological Distress in Mexican Land Defenders" Societies 16, no. 1: 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc16010014

APA StyleNuñez Fadda, S. M., & Gloss Nuñez, D. M. (2026). Place Attachment Disruption: Emotions and Psychological Distress in Mexican Land Defenders. Societies, 16(1), 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc16010014