1. Introduction

Hikikomori is a Japanese term formed from the words

“引き籠もり” (to pull) and “

引きこもり” (to withdraw), meaning “to stay apart, to withdraw” [

1]. This term was first used in a scientific context—referring both to the syndrome and to individuals affected by it—by psychiatrist Tamaki Saito in 1998. Since voluntary isolation is a prodromal symptom of schizophrenia and major depression, in early diagnoses, Hikikomori syndrome was treated using the pharmacological and nursing therapies provided for schizophrenic patients [

1].

Nevertheless, in most cases, Hikikomori individuals do not exhibit reality distortion or sudden mood swings—hallmarks of schizophrenic disorders. Those who become Hikikomori remain lucid and capable of engaging in complex reasoning [

2,

3,

4].

However, in Adolescence Without End, Saito adopts a radical position, identifying Hikikomori as a new form of isolation linked to a novel psychopathology that is not overlapping with previously known conditions.

Although in some cases long-term social withdrawal leads to evident depressive symptoms, the majority of Hikikomori do not exhibit the typical symptomatology of depression [

5]. Instead, depression appears to be more a consequence of isolation than its cause—this has led several researchers to differentiate between the two psychopathologies [

1,

4,

5].

Consequently, in 2003, the Japanese Ministry of Health officially recognized Hikikomori as a new psychopathology and identified its key characteristics: continuous isolation for six months or longer; motivations for withdrawal stemming from the desire to escape the pressures of social achievement, rather than from an existing psychopathology; and a profound distrust in interpersonal relationships and societal dynamics.

Initially considered a phenomenon confined to Japanese society, Hikikomori has increasingly gained international scholarly attention. Recently, several authors [

5,

6] have documented the emergence of Hikikomori-like syndromes beyond Japan, particularly in economically developed and industrialized societies [

7].

Originally, Hikikomori syndrome emerged as an offline phenomenon [

1]; individuals who chose isolation did so independently of their online presence or use of digital tools, largely because—at the time of initial research—the internet was not yet as developed or pervasive as it is today. However, the current situation appears markedly different. Numerous studies have sought to establish a link between internet usage and the onset of Hikikomori, examining how new media may contribute to severe social withdrawal [

8,

9].

Having become a nearly global phenomenon, it shows marked significant difference among country: in Japan, it is more closely tied to school–work pressures and collectivist norms, prolonged co-residence with family that economically sustains isolation, strong stigma, and a predominance of males; in Western country, it more often emerges within clinical–educational services, with greater family and socioeconomic heterogeneity, unless unbalanced gender distribution, more visible internalizing comorbidities (anxiety, depressive disorders, and autism spectrum disorder, ASD), and digital use serving compensatory and bridging functions [

5,

6,

10,

11].

Today, there is a tendency, especially in public discourse, to confuse Hikikomori with two other disorders: Internet Addiction and Gaming Disorder. In the latter cases, isolation stems from addiction to the internet or video games, whereas in Hikikomori it arises from a broader social malaise not directly linked to external behaviors [

1,

5,

10].

In recent years, however, researchers have found that the internet and video games are often used by Hikikomori as tools for maintaining communication with the outside world and for constructing a form of “secondary sociality,” often with others experiencing similar distress [

11]. Besides this relational function, these tools also provide entertainment during prolonged isolation [

12,

13].

Initial studies conducted by Ricci and Pierdominici indicated that only 30% of Hikikomori were active online, estimating that merely one-tenth of all affected individuals were heavy internet users [

14,

15]. However, these figures have changed significantly, and several recent studies suggest that many Hikikomori now use the internet intensively and continuously during their period of withdrawal [

6].

In this context, the concept of

Compensatory Internet Use (CIU) has recently been introduced in the literature, defined as a retreat into the virtual world of the internet as a means of coping with social deficits and serving as a protective form of isolation from the external world [

16,

17]. Indeed, the use of online games appears to be directly proportional to the prolonged phases of social withdrawal [

18]. Similarly, difficulties in establishing relationships and engaging in social interaction—traits associated with the autistic spectrum—may lead to increased internet usage as a form of pathological social isolation [

19].

Recent literature highlights how the Hikikomori phenomenon has historically been more prevalent among males. However, emerging data suggest a significant increase in female cases in recent years, indicating an evolution in the disorder’s demographic patterns [

20,

21].

While traditional Hikikomori manifested as a radical form of social withdrawal, it was often accompanied by a complete disconnection not only from direct human contact but also from technological means of communication—including telephones, television, and, later, the internet. In the early stages of the phenomenon, individuals who withdrew from society typically severed all forms of connection with the outside world, both physical and digital, leading to a state of near-total isolation [

1,

2,

5].

Traditionally examined through psychological and psychiatric lenses, the Hikikomori phenomenon now is being studied under the digital sociology perspective, which interprets withdrawal as a practice mediated by the affordances of online platforms [

22]. In recent years, however, numerous studies have highlighted how many contemporary Hikikomori make extensive use of the internet. Rather than avoiding technology altogether, they often rely on it as their primary—and sometimes sole—means of interacting with the outside world. Social networks, online video games, forums, and streaming platforms serve as refuges, enabling individuals to maintain a certain degree of social connection, albeit in a virtual and highly selective manner. In some cases, these digital activities function as true surrogates for interpersonal relationships, though paradoxically they may also reinforce physical isolation [

12,

13].

This shift has led some researchers to describe a new form of “digital Hikikomori,” in which social withdrawal does not necessarily entail a total absence of communication, but rather a reconfiguration of relationships within virtual spaces. It is particularly noteworthy that certain applications—such as Pokémon Go, as analyzed by Walter and Olczyk [

20]—have paradoxically encouraged users, including socially withdrawn individuals, to leave their homes and interact with their physical environment, albeit within a gamified and technologically mediated framework. This suggests that while digital technologies can contribute to social isolation, they may also serve as tools for gradually re-engaging with society.

This dichotomy is reflected in digital usage patterns. We adopt Internet use as the central analytical lens and introduce the notion of the digital Hikikomori: individuals in prolonged social withdrawal who—unlike “traditional” forms—maintain or even intensify strong online engagement—social media, gaming, chats, and online communities—as an integral part of their daily routines. This engagement should not be conflated with “Internet addiction”; rather, it lies along a pathological–non-pathological continuum and may serve compensatory, identity-forming, relational, and regulatory functions [

21,

23,

24].

Despite growing attention, a structured account that systematically defines the relationship between Hikikomori and the Internet is still lacking. The contribution of this paper is to propose a paradigm shift from “offline” traditional Hikikomori to “digital Hikikomori”, seeking to understand how online presence restructures routines, ties, and identities. The research questions guiding the three phases are therefore:

- −

RS1 (Survey phase): How do families perceive the role of Internet use in the daily withdrawal patterns and household dynamics of their Hikikomori son and daughters?

- −

RS2 (Netnographic phase): How do Hikikomori individuals use digital platforms to construct alternative routines, social connections, and identities during withdrawal?

- −

RS3 (Delphi phase): How do the Internet-based technologies will transform the hikikomori phenomenon?

2. Materials and Methods

The present study aims to explore and describe the phenomenon of Hikikomori. The adopted research approach is primarily exploratory-descriptive, with the objective of gaining a deep understanding of how this phenomenon manifests within the Italian context, in comparison to other territorial settings.

This study does not aim to provide a general theoretical redefinition of the Hikikomori phenomenon, but rather proposes its critical reconceptualization through the lens of digital practices, with particular focus on the Italian context. The objective is to investigate how Internet use—an element absent from original conceptualizations of social withdrawal—is radically reshaping the manifestations and very experience of contemporary Hikikomori.

Another goal of the study is to explore the role and influence of digital technologies and the internet in the lives of Hikikomori individuals. In particular, the study aims to analyze how the internet may serve both as an escape or refuge and as a factor that sustains or reinforces social isolation.

The analysis will thus focus on how such tools influence the experience of social isolation, highlighting their ambivalent role: on one hand, as a means of connection and relational compensation, and on the other, as potentially aggravating factors of social withdrawal.

This perspective may contribute to a shift in the perception of the Hikikomori syndrome, originally characterized as a deeply “offline” phenomenon associated with the rejection of external contact. Interaction with the digital world, in fact, introduces new dynamics that render the phenomenon more complex and multifaceted, raising questions about the evolution of isolation in the digital era.

The research design adopted is a three-phase Complex Mixed Methods Design [

25], with the use of the Internet as the central analytical lens, characterized by a complex/nested structure. The phases were implemented sequentially rather than in parallel, and those presented here correspond to the phases actually carried out in that order.

No data triangulation techniques were employed. It is essential to emphasize that the approach chosen was data integration, not triangulation: triangulation assumes that different techniques can be used as functionally equivalent to capture the same aspects of reality, with the aim of demonstrating the interchangeability of results as an indicator of internal validity; by contrast, integration preserves the specificities of qualitative and quantitative methods—even when combined—in order to access different and non-interchangeable dimensions of the phenomenon. We therefore adopted integration to overcome the limitations inherent in triangulation, as highlighted by Mauceri [

26] and Peters and Fàbregues [

27], considering the findings of the three phases in a complementary manner, leveraging the distinctive contributions of each method and enriching the understanding of the phenomenon under study.

2.1. Survey

The first phase of this research involved quantitative data collection [

28] through the administration of a questionnaire [

29] developed with reference to two previously validated instruments in the psychological and psychiatric fields [

10,

30]. The sample comprised exclusively parents whose sons and daughters had been in social withdrawal for at least six months. The survey consists of 33 items and was completed by 399 participants, yielding a 100% response rate: no item was skipped. Before starting survey, an informed consent module was presented, outlining the study’s aims and purposes and specifying that all data were anonymous and would be used solely for research; if consent was not provided, the questionnaire automatically ended.

Eligible respondents were identified with the support of the association Hikikomori Italia, the principal Italian organization dedicated to supporting individuals with Hikikomori, which operates nationwide with branches in every region. At present, the association has 3756 registered parents; the sample size was calculated with a 95% confidence level and a 5% margin of error. A stratified sampling design was used, with geographic area (Northern, Central, Southern Italy, and the Islands) as the stratification variable.

The questionnaire is divided into two sections, each designed to contribute to a comprehensive understanding of the Hikikomori phenomenon. The first section gathers information on the parents of the Hikikomori; the second collects information on the individual characteristics of the sons exhibiting Hikikomori behaviors, based on the parents’ reports of their children’s experiences. Measures were structured using Cantril scales—already employed in other instruments studying Hikikomori and adapted to the Italian context—for assessing the frequency of attitudes; categorical variables were used for socio-demographic data; and age and months of isolation were collected as continuous variables. The Internet-related variables presented here are dummy (binary) indicators, obtained by asking parents whether each characteristic was present or absent.

2.2. Netnography

The second phase of the study employed a qualitative methodological approach grounded in digital ethnography, specifically netnography [

25,

31,

32,

33], conducted on a single field site—a Telegram group—rather than on a meta-field (aggregates of posts from multiple contexts). Data collection was based on passive, non-interventionist observation within a community of 121 individuals who self-identified as Hikikomori, with access contingent upon administrator authorization to ensure control over membership composition.

The group was selected because it was frequented by youths reporting prolonged domestic isolation, consistent with the Hikikomori profile, and it constituted a pragmatic substitute given the impracticality of conducting direct interviews. Adherence was operationalized, at the observational stage, via recurring narrative indicators: self-identification as Hikikomori, predominant homebound status for ≥6 months, systematic avoidance of school/work and face-to-face interactions, and a marked preference for online, mediated exchanges.

Before formal data collection, one month of silent observation was undertaken to verify members’ fit with the Hikikomori profile; the community’s prior year of activity and high participation rates ensured sufficient informational density. Observation continued for six months (late May–early November 2023) and was ended with the theoretical saturation, when no further salient elements of the phenomenon emerged.

The data collected (approximately 90,000 messages; 1,525,178 characters; 310,168 words; 21,112 unique words) encompassed language use, topics discussed, and emotions expressed, and were analyzed using an inductive, narrative approach [

34], rather than a thematic one: findings are presented through interpreted excerpts without constructing exhaustive taxonomies, in line with the netnographic paradigm [

30,

32]. During the observation period, the number of users declined from 121 to 89, as some members were removed for non-adherence to the Hikikomori profile, demonstrating the group’s self-regulation and its identification of individuals no longer considered to meet the profile.

The platform’s semi-private and mediated nature facilitated confidentiality and self-disclosure, enhancing the ecological validity of interactions; at the same time, member self-selection and administrative gatekeeping may have narrowed the variability of experiences, the absence of probing questions limited the clarification of ambiguities, and the predominance of written text excluded paralinguistic cues. These effects were considered in the interpretation and are explicitly acknowledged in the discussion of results.

2.3. Delphi Method

The final phase of data collection was conducted using the Delphi Method, a well-established iterative approach that engages a panel of experts to reach consensus on specific issues [

35]. It involved 21 experts on the Hikikomori phenomenon and unfolded over five months, from January to April 2024.

Experts were recruited through a dual strategy: in the private sector, via collaboration with the association Hikikomori Italia and the Mite Foundation, both of which work intensively on the phenomenon; and, in parallel, by contacting researchers and university faculty with proven multi-year experience in studying and intervening on the topic. The Delphi investigation comprised three consecutive questionnaires: the first two, each consisting of five open-ended questions, enabled an in-depth examination of the phenomenon and the pursuit of qualitative consensus; the final round moved toward quantitative consensus, employing Cantril scales constructed on the basis of findings from the preceding rounds.

The excerpts presented in this paper, shows in

Table 1, derive primarily from the first two questionnaires, in which experts discussed the relationship between Hikikomori and the web and the Internet.

3. Results

Hikikomori phenomenon, originally emerging predominantly in offline contexts, has undergone significant evolution in recent years due to technological advances and communication tools [

6]. In Italy, the association between Hikikomori and the use of online platforms has been examined through various studies [

35,

36] that have analyzed the nature of this relationship.

3.1. Survey

Survey results indicate that over one-third of the sample involved in the survey regularly uses the internet. However, this finding is not new and may play a significant role in the context of the Hikikomori syndrome, as several authors [

37] suggest that individuals affected by Hikikomori tend to engage in frequent use of the internet and online platforms.

Table 2 presents the responses to the question regarding the intensive use of the internet by Hikikomori individuals in Italy. The data show that a large majority of respondents—71% (285 individuals)—reported that their Hikikomori child uses the internet intensively. This figure suggests that, for many socially withdrawn youths, the internet constitutes a fundamental component of their daily lives. Indeed, the internet can become a tool for entertainment, communication with the outside world, or a form of refuge and protection from the real world.

On the other hand, 29% of participants (114 individuals) stated that they did not observe excessive internet use by their loved one. While representing a minority, this finding is significant as it highlights the existence of a segment of the Hikikomori population that experiences isolation in a more “traditional” manner, without heavy reliance on digital technologies.

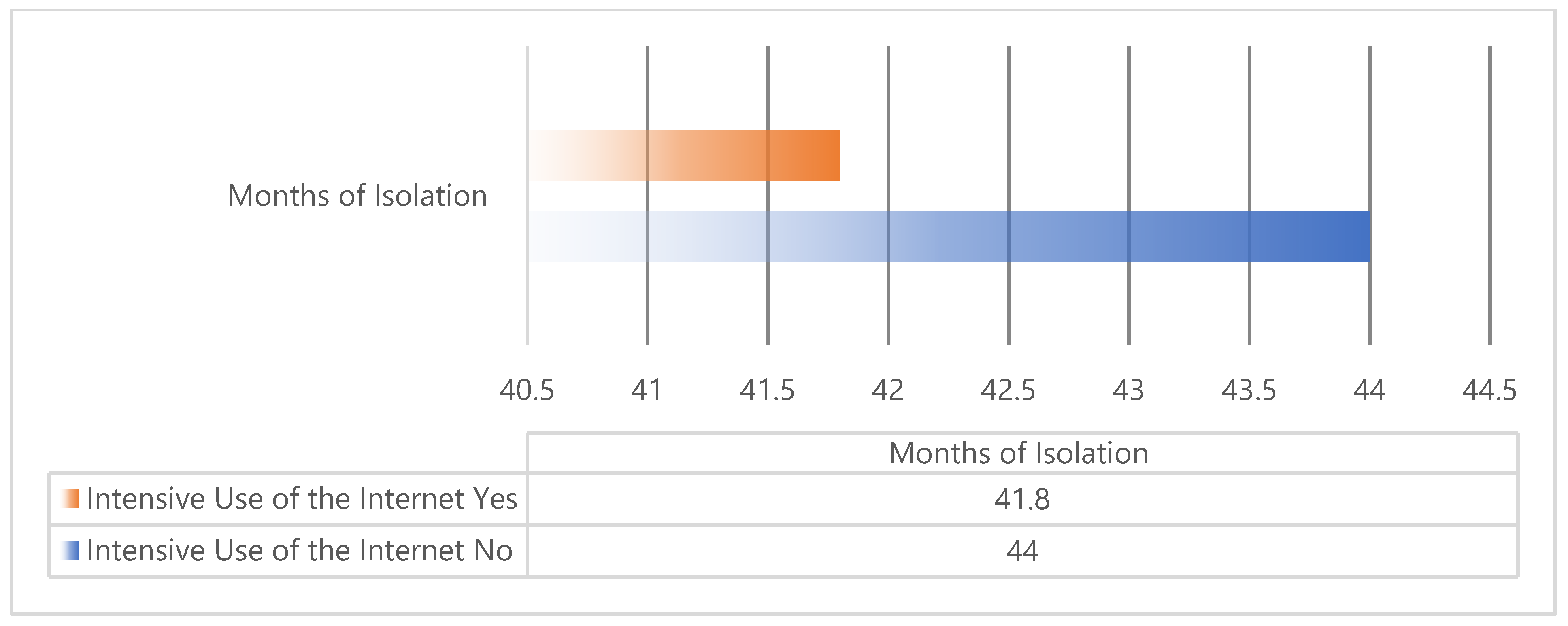

The findings of the research suggest a relationship between intensive internet use and less prolonged isolation among individuals affected by hikikomori, ah shows

Figure 1. This may indicate that internet use could play a significant role in facilitating social reconnection for those who have withdrawn from social interaction, allowing them to maintain social ties through online networks. Conversely, individuals who do not engage with social media or online platforms—more aligned with the traditional hikikomori profile—appear to experience a more extended period of isolation.

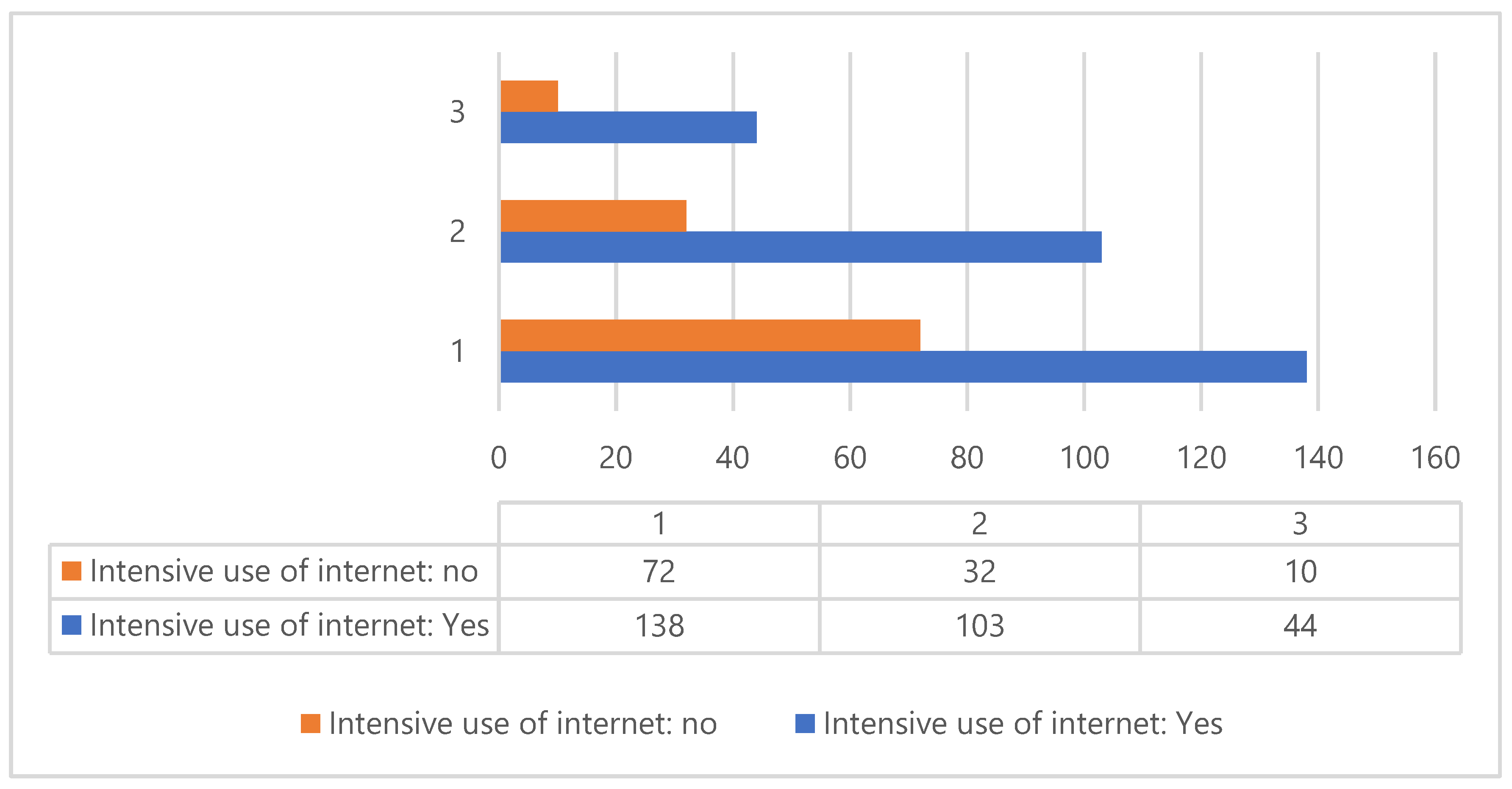

In all the geographic areas analyzed (

Figure 2), the majority of respondents reported intensive internet use by their hikikomori family member, thus confirming a consistent trend across the national territory.

These data align consistently with those concerning the nature of online interaction: as shown

Table 3 most hikikomori individuals maintain social relationships through the web, with particularly high percentages in the South and Islands (81.5%) and the Center (76.3%), and slightly lower figures in the North (65.7%). The association between geographic area and the maintenance of online relationships is statistically significant (

p = 0.02) and of small-to-moderate magnitude (Cramer’s V = 0.238; Phi = 0.239), indicating that the pattern varies by region but with an overall modest effect.

This indicates that social withdrawal does not necessarily imply a complete severance of relationships, but rather a reorganization of them in a digital form. Online interaction thus emerges as a selective and mediated form of sociability, allowing hikikomori to maintain connections, albeit in atypical and often anonymous ways.

Therefore, internet use does not appear to be merely a passive pastime, but rather an active tool for socialization. This dynamic seems to challenge the stereotypical image of the completely isolated hikikomori and suggests that over time the internet has begun to play a crucial role in redefining the very concept of isolation.

The recent interpretative evolution of the hikikomori phenomenon also unfolds through the conceptual distinction between primary and secondary forms of social withdrawal. As highlighted in the scientific literature [

5,

38], a primary hikikomori is defined as an individual who exhibits social isolation behaviors in the absence of any diagnosed psychopathologies. In these cases, the tendency to withdraw is attributed to relational, existential, or cultural factors rather than to an underlying clinical disorder. In contrast, secondary hikikomori is characterized by comorbidity with pre-existing psychopathological conditions, such as depression, schizophrenia, or social phobia, with the isolation behavior serving as a secondary symptom to the main pathology. In these latter cases, exiting the withdrawal condition appears possible in conjunction with the treatment and resolution of the associated psychological disorder [

5,

11].

In absolute terms (

Table 4), out of a total of 245 primary hikikomori, 170 report regular internet use, while 75 do not. Among secondary hikikomori, 115 out of 154 report frequent internet usage, compared to 39 who use it rarely or not at all.

These findings suggest that, although there is a slight difference between the two categories—with a marginally higher incidence of internet use among secondary hikikomori—the intensive use of digital technologies represents a transversal feature of the phenomenon. The widespread use of the internet across both types may indicate that, regardless of the presence of psychopathological comorbidities, the online environment plays a functional and adaptive role for these individuals.

For primary hikikomori, the digital sphere may serve as an alternative space for self-expression, identity construction, and the maintenance of protected forms of social interaction, consistent with a deliberate strategy of withdrawal from the physical social environment. For secondary hikikomori, internet use may serve a compensatory function in response to the limitations imposed by their clinical conditions, acting as an indirect psychological support and, in some cases, as an initial step toward potential social reactivation.

3.2. Netnography

The evolution of the hikikomori concept finds a particularly significant expression in the analysis of interactions within the Telegram group observed, which highlights a notable change in perspective compared to the traditional representation of the phenomenon. In this context, internet use assumes a central role for users, substantially contributing to the redefinition of socialization models typical of hikikomori individuals. The network, in this sense, is no longer just a means of escape but a true alternative social space that allows forms of connection, belonging, and exchange, even if in non-conventional modes:

“User 1: If someone seeks refuge online to find friends or relationships, they are not doing very well socially.”

(Telegram Group User, Male)

“User 2: I disagree with your opinion.”

(Telegram Group User, Male)

The group has gained considerable importance as a tool for meeting and sharing experiences and opinions among individuals seeking new friendships. This perspective marks a significant change from the traditional behavior of hikikomori in Japan, characterized by a strong tendency to social withdrawal and rejection of all forms of human interaction outside the home environment. This phenomenon, described by Teo [

10], Crepaldi [

5], is thus an innovative and diversified approach to sociability and interpersonal communication among those involved.

The association between internet and hikikomori seems to suggest a link between hikikomori and the opportunities offered by the internet for work and study. This scenario contrasts with more consolidated representations found in Japanese literature on hikikomori but aligns with evidence from studies conducted in European contexts [

11,

39].

It is interesting to note how the internet has profoundly influenced the social dynamics of hikikomori. Through the network, many users affected by loneliness have organized themselves and created online groups to connect with others sharing their condition. These groups can provide a virtual space where hikikomori can find a sense of belonging, share similar experiences, and establish social relationships through the internet:

“User 1: No, but online you can be yourself or pretend to be anyone.”

(Telegram Group User, Male)

“User 2: You can still find friends. Social deficits are alleviated.”

(Telegram Group User, Female)

“User 1: Exactly, this also applies to ‘normies,’ but for people like us with various issues, we will inevitably find problematic people like us. Friends, big word, more like people to talk to, maybe.”

(Telegram Group User, Male)

The use of internet by hikikomori appears as an ambivalent tool that, on the one hand, can facilitate contact with the outside world, but, on the other hand, can also cause conflicts and relational problems:

“User 1: On the internet, I do nothing, but when it comes to people you meet, it’s a problem because after trying to meet someone, any subsequent encounter is completely filled with a sense of shame (I don’t know how to describe it otherwise), if you try, you have to accept that maybe you won’t see that person for a long time or they will disappear.”

(Telegram Group User, Male)

“User 2: That’s crazy.”

(Telegram Group User, Male)

“User 3: For us who have no friends at all, a problem like that will never come up.”

(Telegram Group User, Male)

“Already, I imagined it there, full of friends made in this group… The harsh reality is that it will be like a dog.”

(Telegram Group User, Male)

This appears to highlight a novel dimension of the phenomenon: contrary to the traditional portrayal of hikikomori as entirely disengaged from society, the corpus analysis shows that some individuals utilize digital resources to maintain ties with education while avoiding physical interactions. Thus, the table not only empirically validates this observation but also provides a quantitative basis for reinterpreting the role of the Internet in contemporary social withdrawal.

Contrary to traditional conceptualizations originating from Japanese clinical observations [

5,

10]—which characterize hikikomori as complete social disengagement including academic abandonment—our netnographic corpus demonstrates an adaptive dimension of withdrawal. Participants frequently associate Internet use with educational maintenance, describing remote learning strategies that enable academic credential attainment while minimizing stressful physical interactions.

This finding aligns with emerging European research [

11,

39] suggesting the Internet serves as a functional alternative space for socially withdrawn individuals. Rather than representing mere isolation, digital platforms appear to facilitate atypical forms of educational participation and professional development. The quantitative correlations substantiate qualitative reports of Internet-enabled autonomy, where users access educational content and complete degree programs despite avoiding traditional social contexts.

The observed patterns challenge dichotomous interpretations of hikikomori as either complete disengagement or functional adaptation. Instead, they support a continuum model where digital technologies mediate withdrawal behaviors, simultaneously enabling educational persistence while reinforcing social avoidance. This dual functionality of Internet use warrants reconsideration of intervention frameworks to account for technology’s role in maintaining functional capabilities during withdrawal periods.

3.3. Delphi Method

Experts indicate on the Internet a crucial way out for hikikomori, who, thanks to it and digital platforms, can alleviate the suffering of social isolation:

“It’s a fact that many hikikomori have particular predispositions regarding internet use, social networks, and especially video games because, through these, they sometimes feel they can better reveal their personality online than how they express it offline. However, new technologies often appear as a kind of cure rather than the cause: the PC allows communication that would otherwise not happen. In my cases, in fact, the web essentially represents the tool they frequently use to maintain relationships with the outside world, to create interpersonal and social relations that they otherwise cannot have.”

(Sociologist, 54 years old)

For experts, Internet is not considered one of the main causes of isolation or a factor that reinforces hikikomori’s withdrawal. On the contrary, it is often regarded as a solution and a tool through which secondary sociality can develop, helping hikikomori to make their social withdrawal less oppressive:

“Internet allows hikikomori young people to open up to the outside; it is the only window to the world, the only way to talk with peers and others, to play, to have social contact, to experience emotions—all of which would be impossible without the internet and with such strong withdrawal. Sometimes, the internet even becomes the only therapeutic access to these boys’ world.”

(Psychologist, 56 years old)

Experts agree that Internet plays a central role in the daily life of hikikomori, often representing the last window to the world for these young people living in social isolation. However, it is important to emphasize that, according to experts, internet use is not the cause of social withdrawal but rather a refuge and an escape opportunity for individuals affected by this condition:

“The role of internet is fundamental in the daily life of a young person living a social withdrawal; not with a negative connotation, as often happens, but as a refuge and the only window to the world that allows them to maintain a virtual contact with the outside. It’s a reassuring refuge where one feels competent and can live relationships that are less exhausting than face-to-face ones. Furthermore, it is used as an information tool (though those who fall into information overload risk experiencing the withdrawal in its most severe form, with possible psychotic slips, as even virtual relationships are not maintained.”

(Clinical Psychologist, 62 years old)

According to experts, the internet now plays a significant role in the phenomenon of Western hikikomori. The position held is that many individuals who develop this disorder become reclusive due to their dependence on the internet, through which they progressively transfer their interests and activities. Therefore, for hikikomori who primarily withdraw online, it becomes particularly difficult to define their identity independently, unlike those who do not resort to the web:

“The role of the internet, at least for Western hikikomori, is decisive. Cyberspace has created the possibility of living and ‘inhabiting’ spaces without having to expose a body, thus avoiding social judgment. I invite you to reflect on the concept of ‘digital migration,’ which is fundamental to understanding whether we are dealing with a ‘clinical’ hikikomori.”

(Clinical Psychologist, 62 years old)

A significant part of the investigation focuses on analyzing the possible evolutionary trajectories of hikikomori. In this regard, two main interpretative orientations emerge. The first suggests that the phenomenon is destined for gradual expansion, should the social context continue to reinforce stigmatization processes against atypical forms of social withdrawal. The second orientation, however, emphasizes the current impossibility of making certain predictions about the phenomenon’s evolution, given its multidimensional complexity. Nonetheless, in the Italian context, several experts observe an emerging trend toward forms of “semi-withdrawal,” characterized by a partial reduction in social contacts rather than complete isolation, thus outlining new configurations of the phenomenon:

“The complexity of the phenomenon is such that it is impossible to predict possible and certain trajectories regarding its “social and psychological” evolution. In recent months, it seems that the phenomenon is more expressed through forms of semi-withdrawal. We mean forms in which, in some ways, the young person does not completely withdraw from the social and school scene, but certainly manifests fragility and vulnerability in these dimensions. In fact, such forms of withdrawal allow the young person to preserve certain spaces for growth and to invest more functionally in emotional and cognitive resources.”

(Psychologist, 56 years old)

4. Discussion

The conceptualization of the hikikomori phenomenon is relatively recent and, consequently, the available scientific literature remains limited, particularly with respect to interactions between this condition and new technologies. Nevertheless, a significant increase in studies on the topic is anticipated, driven both by growing international interest and by the continual evolution of the technological landscape. Owing to rapid changes in the digital realm, definitional issues have progressively extended into the online context, making it necessary to broaden traditional conceptual boundaries in order to adequately describe new manifestations of the phenomenon.

The findings emerging from the investigation, together with the testimonies collected, make a significant contribution to understanding Hikikomori, highlighting a conceptual evolution that departs from the traditional representation of social isolation as an exclusively offline condition. Integrating the digital dimension shows that, for many individuals in a state of social withdrawal, the internet is not merely a tool for passive entertainment but an active resource through which relationships can be built, identities expressed, and contact with the external environment maintained, albeit in mediated form [

40,

41].

Such evidence appears to suggest the emergence of “hybrid” forms of withdrawal, in which physical isolation does not necessarily equate to a total absence of social interactions.

The research integrates three phases, collectively illustrating the internet’s role as an active facilitator of mediated sociability. Phase 1′s survey data reveal that 71% of participants engage in intensive internet use, which correlates with a statistically significant reduction in isolation duration (p = 0.04; Cramer’s V = 0.433). This suggests that online connectivity can alleviate the most severe consequences of social withdrawal by maintaining interpersonal contacts and reinforcing daily routines. Phase 2, which employs netnographic methods, corroborates and elaborates on these findings: interactions within the observed Telegram group highlight the internet as a viable alternative social space that fosters a sense of belonging, mitigates perceived social deficits, and supports distance learning and identity construction. Finally, Phase 3, utilizing the Delphi method, provides a coherent interpretive framework, indicating that experts do not see digital technologies as primary drivers of withdrawal. Instead, they view these technologies as potential “last access” points of therapeutic and relational value, facilitating forms of secondary sociability and gradual re-engagement strategies.

A second key finding highlights the widespread adoption of digital technology across various clinical profiles. The survey reveals that both primary hikikomori (170 indicating usage versus 75 not) and secondary hikikomori (115 indicating usage versus 39 not) demonstrate intensive digital engagement. This empirical overlap suggests that the use of digital technologies is an inherent aspect of the phenomenon, rather than simply linked to the presence or absence of psychopathological comorbidity. In essence, the online environment serves adaptive and relationally regulatory functions that transcend clinical diversity, while taking on different meanings and roles based on individual and family contexts.

Ultimately, all phases contribute to a nuanced understanding of hybrid withdrawal trajectories: isolation does not equate to a complete exit from the social realm but rather signals a reorientation of connections towards digital contexts. The “digital migration” referenced by experts in the Delphi study, along with the selective sociability observed in the netnography, supports the shift beyond the “real vs. virtual” dichotomy towards an offline–online continuum. Within this framework, individuals renegotiate their modes of participation, belonging, and agency. Thus, the interplay between quantitative data (from surveys) and qualitative insights (from netnography and Delphi) encourages a reexamination of interpretive models of hikikomori, recognizing that the digital realm serves not only as a refuge but also as a relational infrastructure, potentially facilitating a gradual return to social engagement.

However, the integrated analysis of these materials also reveals the micro-relational complexities inherent in mediated sociability. While there are benefits in terms of support and belonging, these are coupled with various tensions and risks associated with the offline manifestation of relationships, such as feelings of shame, embarrassment, unmet expectations of friendship, and challenges stemming from managing fragile or anonymous interactions. These contextual dynamics, which are often overlooked by mere prevalence metrics, shed light on the everyday costs of digital communication and illustrate how strategies for emotional regulation, identity construction, and educational engagement coexist with relational vulnerabilities. From this perspective, a clinical–therapeutic interpretation reconfigures the operational landscape: the digital realm functions simultaneously as a tool for tele-engagement and a “window onto the world,” while demanding attention to the risks of information overload and potential identity shifts when life is primarily lived online, leading to challenges in self-definition.

The evidence suggests moving past the “real vs. virtual” dichotomy towards an offline–online continuum, where individuals renegotiate participation and belonging. This reframes hikikomori, recognizing the digital space as both a refuge and a relational infrastructure that can facilitate gradual social reopening when appropriately mediated. In a Western context, internet use is not just an accessory but integral to the withdrawal experience. As Castell [

42] notes, daily life increasingly exists in a “space of flows,” where digital networks shape the rules of engagement through asynchronous interactions. In this ecosystem, networks support identity and belonging practices through mass self-communication, enabling individuals to create content and establish community ties even without physical presence.

Quantitative evidence (prevalence of intensive use and its association with shorter isolation) and qualitative evidence (belonging, self-presentation, distance learning) converge in indicating that digital participation is not residual but organizational of the withdrawal experience: it provides relational capital and frames of meaning capable of offsetting, at least in part, the friction of face-to-face sociability. The cross-cutting character of such practices across clinical profiles suggests that the digital dimension does not necessarily derive from psychopathological comorbidity but contributes to structuring the phenomenon independently of it, according to network logics—modularity, scalability, and reconfigurability of ties [

13,

42]. It follows that the traditional opposition between the “space of places” and the “space of flows” loses explanatory power: the data describe a hybrid ecosystem in which agency, belonging, and trajectories of functioning are negotiated through reticular connections that traverse and reconnect the two planes. Such a reframing requires interdisciplinary, context-sensitive approaches capable of integrating prevalence, subjective meanings, and therapeutic implications into a coherent reading of the phenomenon and of guiding assessment tools and staged interventions that leverage the digital as a potentially transformative infrastructure.

Given the proposed theoretical framework that positions hikikomori as a phenomenon situated within the context of network society and the “space of flows,” it is crucial to differentiate it from Internet Addiction and Gaming Disorder. Evidence points to a continuum that encompasses both physical isolation and digital engagement, where a variety of hybrid configurations can emerge. Individuals navigating this continuum can sustain relational and formative functions devoid of physical presence, dynamically adjusting the intensity and character of their online interactions to align with their specific needs, contexts, and available resources.

In this light, digital participation assumes multifaceted roles. It can act as a regulatory refuge [

16,

17], afford a platform for self-presentation and community affiliation to foster identity and belonging [

11,

12,

13], and serve as a conduit for micro-reopenings to the offline world. These dynamics operate under network logics such as modularity, scalability, and reconfigurability. Consequently, the traditional dichotomy between the real and the virtual becomes less viable for explanatory purposes; hikikomori should be reconceptualized as a reorganization of social bonds within reticular infrastructures. Within this framework, agency and pathways to functionality are negotiated through mediated connections, which can both entrench withdrawal and facilitate gradual transitions back to the physical world [

42,

43,

44]

The findings discussed seem to outline an offline–online continuum wherein digital engagement takes on varying—often pivotal—roles in influencing the trajectory of withdrawal. In certain instances, internet use serves as a stable refuge: the online environment primarily functions to help regulate anxiety and manage social exposure [

5,

6,

8]. This is characterized by low-reciprocity interactions, homogeneous networks, and predictable routines, which over time may entrench domestic seclusion. At the other end of the spectrum, we observe uses that act as a gradual bridge: moderated settings, clinical–educational tele-engagement, and collaborative activities (including distance learning) foster a sense of belonging and self-efficacy, broaden the diversity of social connections, and facilitate the translation of specific skills and contacts into small re-engagements in the offline world. Between these extremes exist hybrid and dynamic configurations: in the oscillating hybrid profile, phases of withdrawal alternate with attempts at reactivation, displaying notable sensitivity to contextual factors (such as family, school, and work) and irregular patterns of digital participation that necessitate longitudinal monitoring and contingency planning. Conversely, the “traditional” withdrawal profile [

1,

4,

7] is marked by minimal or absent digital engagement, which heightens individuals’ risk of prolonged isolation and diminishes their access to resources, information, and web-mediated pathways for re-engagement.

This reading of the phenomenon may help clarify how internet use, within hikikomori trajectories, can operate now as a regulator and protective container, now as a relational infrastructure oriented toward reopening, or as a valve that modulates oscillation between closure and contact. It also enables the interpretation of territorial differences and clinical profiles as factors that nudge individuals toward one configuration or another: the availability of digital-informed services, the family climate, local educational and employment opportunities, or the presence of comorbidities may facilitate movement from a stable refuge toward a gradual bridge—or, conversely, entrench a more traditional form of withdrawal.

5. Conclusions

While observed across diverse cultural settings, the hikikomori phenomenon demonstrates particularly high prevalence within highly industrialized and globalized societies [

5,

6,

10,

44]. Empirical investigations have consistently identified significant concentrations of hikikomori cases in affluent, technologically advanced nations. Within the Italian context, a growing body of research [

5,

9,

35,

36] has documented a steady epidemiological increase, mirroring global trends while exhibiting distinctive local characteristics.

The actual hikikomori experience is fundamentally shaped by digital engagement, with study findings revealing nearly universal participation in digital technologies among research subjects. This empirical evidence substantiates existing theoretical models that position technology as central to contemporary withdrawal experiences [

18]. Importantly, digital connectivity serves multiple complex functions that extend far beyond simple entertainment or escapism. It operates simultaneously as a sophisticated arena for social interaction, a reflective medium for self-examination, and a transformative platform for identity development and expression.

This profound digital integration [

22,

45] has achieved remarkable consensus across all groups involved in the study—encompassing family members, mental health professionals, and individuals experiencing withdrawal themselves. The convergence of perspectives strongly suggests that internet use represents an essential, structural component of hikikomori phenomenology within the Italian context, rather than merely an ancillary or secondary characteristic. The depth and consistency of digital immersion points to its constitutive role in shaping the very nature of social withdrawal as it manifests in contemporary society.

Studies conducted in various international contexts [

18,

37] show that the use of digital technologies has become an integral part of daily life for many hikikomori, pointing to a transformation in the very concept of social isolation. From this perspective, a broader theoretical reflection is necessary—one that proposes a redefinition of the hikikomori phenomenon by incorporating the digital dimension as a constitutive element. Social withdrawal no longer appears as a condition of total relational absence, but rather as a form of selective sociability, mediated by online platforms and shaped by the new modes of interaction offered by the digital environment.

However, the sampling method adopted in this study introduces a potential bias, as participants were selected through the Hikikomori Italia Association. While this may limit the representativeness of the sample in relation to the entirety of parents with socially withdrawn children, it is important to acknowledge the methodological challenges associated with recruiting this population, which is traditionally difficult to access through institutional or conventional channels. In this regard, the use of an already established organization with a solid network of contacts represents a justifiable choice, capable of facilitating access to a significant—albeit partial—segment of the target population. Future research could aim to produce a broader mapping of the Italian context, providing more comprehensive national data.

Additional limitations of the study concern the netnographic component, which focused on a single online group of hikikomori individuals not directly connected to the parents involved in the quantitative phase. Despite this limitation, the vast amount of information gathered from the selected group helps to compensate for this issue.

Lastly, in the Delphi panel, although the experts involved addressed the hikikomori phenomenon in depth, there was a tendency to frame it within broader problem categories, such as adolescent distress, school difficulties, or psychiatric and psychological comorbidities. While this approach enriches the understanding of the phenomenon from a multidimensional perspective, it also complicates the formulation of a univocal definition, highlighting the need for further interdisciplinary studies aimed at clarifying the theoretical and operational boundaries of hikikomori.

The overall picture appears to indicate a paradigm shift from “offline Hikikomori” to “digital Hikikomori”, with differences between Japan and the West but also shared features linked to Internet use [

44,

46]. Assuming that Hikikomori entails a dimension of digital centrality may guide the formulation of more pertinent public policies, beginning with the updating of operational definitions and monitoring systems to include indicators of usage patterns and online functions. This, in turn, calls for stable intersectoral governance—integrating schools, social services, youth policies, and the third sector—capable of promoting early identification and continuous social care, while simultaneously developing low-threshold access points and e-outreach strategies in the digital spaces actually frequented by young people, in full compliance with privacy and ethical standards.

From this perspective, national programs of digital literacy and digital well-being aimed at families and peers become central instruments, as do structured collaborations with platforms to enable safe reporting procedures, informed moderation practices, and protective protocols. Finally, support for hybrid online/offline socio-educational services—from digital help desks to academic tutoring and educational–vocational guidance—should be accompanied by outcome evaluation mechanisms, thereby consolidating the strategic use of the digital sphere as a lever for social re-engagement and for strengthening institutional capacities for prevention and inclusion.

In conclusion, understanding hikikomori requires an interdisciplinary integration that brings psychopathological dimensions into dialogue with social and cultural factors and with digital communication practices [

1,

10,

11,

28,

38,

39]. This entails adopting multilevel theoretical frameworks—simultaneously considering the individual, the family, institutions, and platform infrastructures—and mixed-method research designs capable of capturing both the phenomenological breadth and the depth of lived experience. Such an approach makes it possible to grasp, in a coordinated way, the clinical mechanisms (emotion regulation, avoidance, comorbidity), the social logics (online relational capital, group norms, family and territorial specificities), and the communicative forms (self-presentation, belonging, mediated learning) that structure the everyday life of withdrawal.

Such an approach would make it possible to translate the conceptual reframing into operational metrics—for example, indicators of the degree and function of digital participation, the stability/fragility of ties, and functional educational, relational, and clinical outcomes—as well as into assessment tools capable of integrating quantitative data, qualitative evidence, and digital traces. This would in turn enable staged, context-sensitive interventions (tele-engagement, moderated online groups, blended offline–online educational and clinical–educational programs) that leverage the digital as a potentially transformative infrastructure, without reductionism, but with attention to the risks of information overload and identity vulnerability. From this perspective, the convergence of clinical, sociological, and educational knowledge constitutes the condition for effective policies and practices oriented toward relational reopening and the sustainability of pathways out of withdrawal.