Socio-Scientific Perspectives on COVID-Planned Interventions in the Homeless Population

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. Data Sources & Research Strategy

2.2. Data Import and Screening

2.3. Data Treatment and Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Country Analysis

| Country | National Strategies for Combatting Homelessness | Additional Investment due to COVID-19 |

|---|---|---|

| USA | 2018-present [5] * - Home, Together (2018) - Expanding the Toolbox (2020) - All In (2022) | The Relief and Economic Security Act (2020) pledged USD 4 billion (USD) [22]. |

| Canada | 2019-present [5] * Reaching Home: Canadas Homelessness Strategy is a community-based | Additional CAD 157.5 million (CAD) on Canada’s Homelessness Strategy [22]. |

| Australia | 2018-Present [5] * There is no official homelessness strategy, but the National Housing and Homelessness Agreement (NAHA) requires state and territory governments to have a publicly available housing and homelessness strategy in place. | The combined additional funding in the five Australian states is AUD 229 million [22]. |

| Germany | Current programme [5] The National Action Plan Against Homelessness, “Together for a home,” approved in April 2024. | - |

| Hungary | There is no reported homelessness strategy at the national level (OECD, 2024) [5]. | - |

| South Africa | There is no official strategy specifically for people experiencing homelessness; however, the National Department of Human Settlements (NDHS) has a housing strategy in place (https://www.dhs.gov.za/ (accessed on 25 June 2025)). | Allocations were made to a solidarity fund to help combat the spread of the virus, with assistance from private contributions, and support municipal provision of emergency water supply, increased sanitation in public transport, and food and shelter for the homeless [50]. |

3.2. Place-Based Analysis

3.3. Thematic Analysis

3.3.1. Prevention

| Cite | Topic | Place | Location |

|---|---|---|---|

| [58] | COVID-19 vaccination outreach service for the homeless | Region | Torres Strait Islands, Australia |

| [70] | Peer support workers in a primary and community care clinic that serves the homeless | Clinic | Montreal, Canada |

| [71] | Isolation in a hospital building (safety-net hospital) for COVID-infected homeless people | Hospital | Boston, USA |

| [74] | COVID-19 Community Response Team, a partnership between hospitals and shelters as part of an outbreak prevention program | Hospitals and shelters | Toronto, Canada |

| [59] | Cross-sector partnership to enhance COVID vaccine confidence among Youth Experiencing Homelessness | County | Minneapolis, USA |

| [72] | Multiagency COVID-19 isolation and quarantine site tailored for people experiencing homelessness | Hotel | Baltimore, USA |

| [60] | COVID-19 vaccination program to promote the vaccine for the homeless | County | Los Angeles, USA |

| [61] | Inclusive COVID-19 information material to strengthen infection prevention and control for the homeless | City | Berlin, Germany |

| [73] | Temporary medical respite shelter for the homeless | Shelter | Chicago, USA |

| [62] | Community pop-up clinic to achieve high levels of vaccination among residents (homeless people) | City | Vancouver, Canada |

3.3.2. Substance-Related Disorders

| Cite | Topic | Place | Location |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brothers et al. (2022) [54] | Hotel isolation for the COVID-infected homeless with a health care team | Hotel | Halifax, Canada |

| Huggett et al. (2021) [53] | Hotel-based protective housing intervention to reduce the incidence of COVID-19 in the homeless | Hotel | Chicago, USA |

| Marcus et al. (2020) [55] | Stadium-based homeless shelter | Stadium | Tshwane, South Africa |

| Samuel et al. (2022) [56] | Prescribed buprenorphine program partnership among Behavioural Health Services Pharmacy and Shelter in Place (SIP) hotels to Opioid Use Disorder homeless | Hotel | San Francisco, USA |

| Tan et al. (2025) [57] | Shelter-in-place hotel program to provide non-congregate shelter to people experiencing homelessness and vulnerable to SARS-CoV-2 infections | Hotel | Kingston, Canada |

3.3.3. Health Care

| Cite | Topic | Place | Location |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baggett et al. (2020) [65] | Health Care (COVID-19 care model) for the Homeless Program | City | Boston, USA |

| Békási et al. (2022) [63] | Telehealth for the homeless using shelters | City | Budapest, Hungary |

| Fuchs et al. (2021) [52] | Hotel-based COVID-19 isolation care system for the homeless | Hotel | San Francisco, USA |

| Meray et al. (2022) [64] | Telemedicine Homeless Monitoring Project | County | Miami, USA |

| Montgomery et al. (2021) [80] | Isolation hotel for the homeless with COVID-19 and a noncongregate hotel for PEH without COVID-19 but at risk of severe illness | Hotel | Atlanta, USA |

3.3.4. Diagnostic

3.4. Emerging Issues

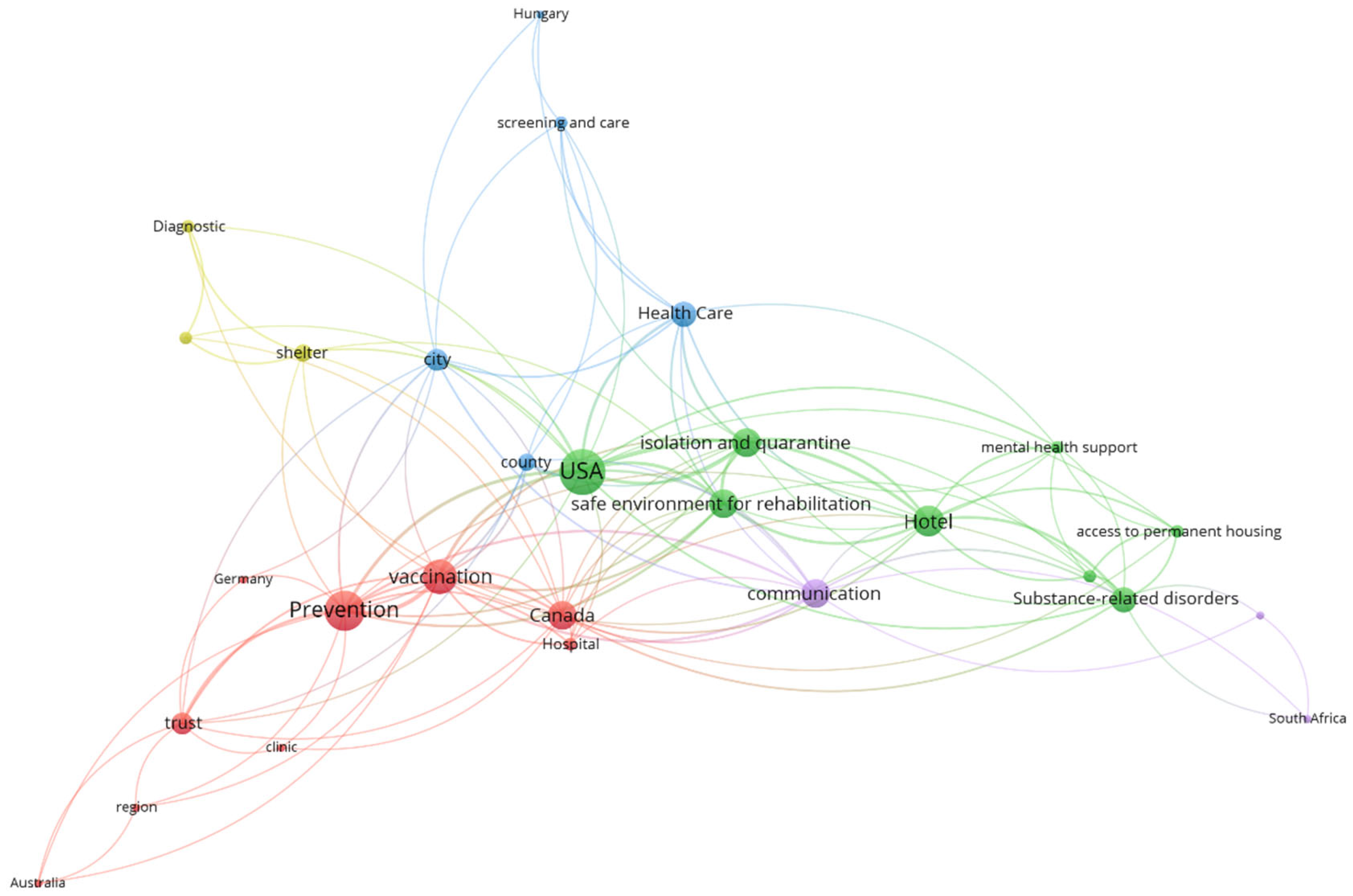

3.5. Thematic Relationships

| Other Support | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psychosocial Support | Prevention | No Other Support | |||

| Health | Diagnostic | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (9.1) | 2 (9.1) |

| Health support | 4 (18.2) | 8 (36.4) | 4 (18.2) | 16 (72.7) | |

| No health action | 2 (9.1) | 2 (9.1) | 0 (0) | 4 (18.2) | |

| Total | 6 (27.3) | 10 (45.5) | 6 (27.3) | 22 (100) | |

4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 |

References

- World Health Organisation [WHO]. WHO Timeline—COVID-19. 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/es/news/item/27-04-2020-who-timeline---covid-19 (accessed on 4 May 2025).

- Pleace, N.; Baptista, I.; Benjaminsen, L.; Busch Geertsema, V.; O’Sullivan, E.; Teller, N. European Homelessness and COVID-19. European Observatory on Homelessness & FEANTSA. 2021. Available online: https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/id/eprint/173020/ (accessed on 4 May 2025).

- Agulles Martos, J.M. COVID-19, personas sin hogar y respuesta institucional. Reflexiones desde la ciudad de Alicante (España). Cuad. Trab. Soc. 2022, 35, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. COVID-19: Protecting People and Societies. 2020. Available online: https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/view/?ref=126_126985-nv145m3l96&title=COVID-19-Protecting-people-and-societies (accessed on 4 May 2025).

- OECD. HC3.2. National Strategies for Combatting Homelessness. 2024. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/data/datasets/affordable-housing-database/hc3-2-homeless-strategies.pdf (accessed on 4 May 2025).

- Ogbonna, O.; Bull, F.; Spinks, B.; Williams, D.; Lewis, R.; Edwards, A. Interventions to mitigate the risks of COVID-19 for people experiencing homelessness and their effectiveness: A systematic review. Front. Public Health 2024, 11, 1286730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calvo, F.; Turró-Garriga, O.; Solench-Arco, X.; Lorenzo-Aparicio, A. ¿Qué pasó con las personas en situación de sinhogarismo durante el confinamiento? Estudio sobre la percepción de profesionales sobre las medidas tomadas ante el estado de alarma por el COVID-19. RES Rev. Educ. Soc. 2020, 31, 373–403. Available online: https://eduso.net/res/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/miscelanea_fran_calvo_res_31.pdf (accessed on 4 May 2025).

- Fenley, V.M. Everyday citizenship and COVID-19: “Staying at home” while homeless. Adm. Theory Prax. 2021, 43, 245–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farha, L. COVID-19 Guidance Note: Protecting Those Living in Homelessness. Special Rapporteur on the Right to Adequate Housing. Office of the High Commissioner of UN Human Rights. 2020. Available online: http://unhousingrapp.org/user/pages/07.press-room/Guidance%20Note%20Homelessness%20Actual%20Final%202%20April%202020[2].pdf (accessed on 4 May 2025).

- Buraschi, D.; Díez, J.A.; Peñate, Ú. Sinhogarismo: El punto ciego del Estado de Bienestar durante la crisis del COVID-19. Arx. Ciències Soc. 2023, 48, 38–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díez Dávila, J.A.; Peñate Martín, Ú.M. Las Personas en Exclusión Residencial Extrema en la isla de Tenerife. Documentación Social. 2023. Available online: https://documentacionsocial.es/contenidos/a-fondo/las-personas-en-exclusion-residencial-extrema-en-la-isla-de-tenerife/ (accessed on 4 May 2025).

- Bedmar, M.A.; Bennasar-Veny, M.; Artigas-Lelong, B.; Salva-Mut, F.; Pou, J.; Capitán-Moyano, L.; García-Toro, M.; Yáñez, A. Health and access to healthcare in homeless people. Medicine 2022, 101, e28816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doherty, J. El origen del sinhogarismo: Perspectivas europeas. Doc. Soc. 2005, 138, 41–62. [Google Scholar]

- Matulic, M.V. Nuevos Perfiles de Personas sin Hogar en la Ciudad de Barcelona: Un Reto Pendiente de los Servicios Sociales de Proximidad. Doc. Trab. Soc. Rev. Trab. Acción Soc. 2010, 48, 9–30. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/descarga/articulo/3655827.pdf (accessed on 4 May 2025).

- Shinn, M. International homelessness: Policy, socio-cultural, and individual perspectives. J. Soc. Issues 2007, 63, 657–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, G.; Pleace, N. How do we measure success in homelessness services? Critically assessing the rise of the Homelessness Outcomes Star. Eur. J. Homelessness 2016, 10, 31–51. Available online: https://www.feantsaresearch.org/download/10-1_article_24170470439113543118.pdf (accessed on 4 May 2025).

- European Federation of National Organisations [FEANTSA]. Report: 8th Overview of Housing Exclusion in Europe 2023. 2023. Available online: https://www.feantsa.org/public/user/Resources/reports/2023/OVERVIEW/Rapport_EN.pdf (accessed on 4 May 2025).

- United Nations General Assembly Universal Declaration of Human Rights. 1948. Available online: https://docs.un.org/en/A/RES/217(III) (accessed on 4 May 2025).

- Laparra, M.; Pérez Eransus, B. La exclusión social en España: Un espacio diverso y disperso en intensa transformación. In VI Informe Sobre Exclusión y Desarrollo Social en España; Fundación FOESSA y Cáritas Española: Madrid, Spain, 2008; pp. 173–205. [Google Scholar]

- Alkire, S.; Santos, M.E. Measuring acute poverty in the developing world: Robustness and scope of the multidimensional poverty index. World Dev. 2014, 59, 251–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Federation of National Organisations [FEANTSA]. The Impact of COVID-19 on Homeless Service Providers & Homeless People: The Migrant. 2021. Available online: https://www.feantsa.org/public/user/Resources/reports/Report_Cov19_&_migrants.pdf (accessed on 4 May 2025).

- Parsell, C.; Clarke, A.; Kuskoff, E. Understanding responses to homelessness during COVID-19: An examination of Australia. Hous. Stud. 2022, 38, 8–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronconi, L. Homeless People, COVID-19 and the Insufficient and Discriminatory Measures Adopted by the City of Buenos Aires’s Government. J. Hum. Rights Soc. Work 2022, 7, 256–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. Statement on the Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Pandemic and Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. United Nations. 17 April 2020. Available online: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/3856957/files/E_C.12_2020_1-EN.pdf (accessed on 4 May 2025).

- Andrade de Souza, A.; Jorge Martins, A.L.; Drummond Marques da Silva, G.; de Moraes Teixeira Vilela Dantas, A.C.; Alves Marinho, R.; da Matta Machado Fernandes, L.; Miranda Magalhães Júnior, H.; Debortoli, W.; Paes-Sousa, R. Study on access to social protection policies by homeless people during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur. J. Public Health 2024, 34 (Suppl. S3), ckae144.2164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martino, E.; Mansour, A.; Bentley, R. Housing Vulnerability and COVID-19 Outbreaks: When Crises Collide. Urban Policy Res. 2022, 41, 6–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Sullivan, E.; Benjaminsen, L.; Busch-Geertsema, V.; Filipovič Hrast, M.; Pleace, N.; Teller, N. Homelessness in the European Union. Publications Office of the European Union. 2023. Available online: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2861/4272 (accessed on 4 May 2025).

- Botija, M.; Panadero, S.; Matulic, M.V. Las personas en situación de sinhogarismo en la Agenda 2030. Rev. Prism. Soc. 2024, 44, 1–3. Available online: https://revistaprismasocial.es/article/view/5400 (accessed on 4 May 2025).

- Ralli, M.; Cedola, C.; Urbano, S.; Latini, O.; Shkodina, N.; Morrone, A.; Arcangeli, A.; Ercoli, L. Assessment of SARS-CoV-2 Infection through Rapid Serology Testing in the Homeless Population in the City of Rome, Italy. Preliminary Results. J. Public Health Res. 2020, 9, 556–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owen, R.; Matthiessen, M. COVID-19 Response and Homelessness in the EU. European Journal of Homelessness. 2021. Available online: https://www.feantsa.org/public/user/Observatory/2021/EJH_15-1/EJH_15-1_RN1_Web.pdf (accessed on 4 May 2025).

- Daly, M. Abandoned: Profile of Europe’s Homeless People; The Second Report of the European Observatory on Homelessness; FEANTSA: Brussels, Belgium, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Kupferschmidt, K. Preprints bring “firehose” of outbreak data. Science 2020, 367, 963–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres Salinas, D. Ritmo de crecimiento diario de la producción científica sobre COVID-19. Análisis en bases de datos y repositorios en acceso abierto. Prof. Inf. 2020, 29, e290215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capitán Moyano, L.; Bedmar Pérez, M.Á.; Artigas Lelong, B.; Bennasar Veny, M.; Pou Bordoy, J.; Molina Núñez, L.; Gayà Coll, M.; Garcias Cifuentes, L.; García Toro, M.; Yáñez Juan, A.M. Personas sin hogar y salud: Vulnerabilidad y riesgos durante la pandemia de COVID-19. Estudio piloto. Acad. J. Health Sci. Med. Balear 2021, 36, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Fuente Roldán, I.N.; Sánchez Moreno, E. Exclusión social y pandemia: La experiencia de las personas en situación de sinhogarismo. Empiria Rev. Metodol. Cienc. Soc. 2023, 58, 123–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiter, S.; Bermpohl, F.; Krausz, M.; Leucht, S.; Rössler, W.; Schouler-Ocak, M.; Gutwinski, S. The Prevalence of Mental Illness in Homeless People in Germany. Dtsch. Aerzteblatt Int. 2017, 114, 665–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calvo, F.; Turró-Garriga, O.; Fàbregas, C.; Alfranca, R.; Calvet, A.; Salvans, M.; Giralt, C.; Castillejos, S.; Rived-Ocaña, M.; Calvo, P.; et al. Mortality risk factors for individuals experiencing homelessness in Catalonia (Spain): A 10-year retrospective cohort study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gläser, J.; Glänzel, W.; Scharnhorst, A. Same data—Different results? Towards a comparative approach to the identification of thematic structures in science. Scientometrics 2017, 111, 981–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Schuehle, J.; Porter, A.L.; Youtie, J. A systematic method to create search strategies for emerging technologies based on the Web of Science: Illustrated for ‘Big Data’. Scientometrics 2015, 105, 2005–2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar-Moya, R.; Melero-Fuentes, D.; Navarro-Molina, C.; Aleixandre-Benavent, R.; Valderrama-Zurián, J.C. Disciplines and thematics of scientific research in police training (1988–2012). Polic. Int. J. Police Strateg. Manag. 2014, 37, 696–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valderrama-Zurian, J.C.; Melero-Fuentes, D.; Aleixandre-Benavent, R. Origin, characteristics, predominance and conceptual networks of eponyms in the bibliometric literature. J. Informetr. 2019, 13, 434–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.J.; Bogdan, R. Introducción a Los Métodos Cualitativos de Investigación; John Wiley and Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. How to normalize cooccurrence data? An analysis of some well-known similarity measures. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2009, 60, 1635–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waltman, L.; Van Eck, N.J.; Noyons, E.C. A unified approach to mapping and clustering of bibliometric networks. J. Informetr. 2010, 4, 629–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjaminsen, L.; Muñoz, M.; Vázquez, C.; Panadero, S. Quantitative methods in homelessness studies: A critical guide and recommendations. In Proceedings of the Conference on Research on Homelessness in Comparative Perspective 2005, Brussels, Belgium, 3–4 November 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Toro, P.A. Toward an international understanding of homelessness. J. Soc. Issues 2007, 63, 461–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levesque, J.; Babando, J.; Loranger, N.; Johnson, S.; Pugh, D. COVID-19 prevalence and infection control measures at homeless shelters and hostels in high-income countries: A scoping review. Syst. Rev. 2022, 11, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Basu, M.; Ghosh, P.; Ansari, A.; Ghosh, M.K. COVID-19: Clinical status of vaccine development to date. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2023, 89, 114–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Bank. The World by Income and Region. Available online: https://datatopics.worldbank.org/world-development-indicators/the-world-by-income-and-region.html (accessed on 4 May 2025).

- International Monetary Fund. Available online: https://www.imf.org/en/Topics/imf-and-covid19/Policy-Responses-to-COVID-19 (accessed on 4 May 2025).

- Shinn, M. Homelessness, Poverty and Social Exclusion in the United States and Europe. Eur. J. Homelessness 2010, 4, 19–44. Available online: https://www.feantsaresearch.org/download/article-1-23498373030877943020.pdf (accessed on 4 May 2025).

- Fuchs, J.D.; Carter, H.C.; Evans, J.; Graham-Squire, D.; Imbert, E.; Bloome, J.; Fann, C.; Skotnes, T.; Sears, J.; Pfeifer-Rosenblum, R.; et al. Assessment of a hotel-based COVID-19 isolation and quarantine strategy for persons experiencing homelessness. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e210490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huggett, T.D.; Tung, E.L.; Cunningham, M.; Ghinai, I.; Duncan, H.L.; McCauley, M.E.; Detmer, W.M. Assessment of a hotel-based protective housing program for incidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection and management of chronic illness among persons experiencing homelessness. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2138464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brothers, T.D.; Leaman, M.; Bonn, M.; Lewer, D.; Atkinson, J.; Fraser, J.; Gillis, A.; Gniewek, M.; Hawker, L.; Hayman, H.; et al. Evaluation of an emergency safe supply drugs and managed alcohol program in COVID-19 isolation hotel shelters for people experiencing homelessness. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2022, 235, 109440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcus, T.S.; Heese, J.; Scheibe, A.; Shelly, S.; Lalla, S.X.; Hugo, J.F. Harm reduction in an emergency response to homelessness during South Africa’s COVID-19 lockdown. Harm Reduct. J. 2020, 17, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samuel, L.; Caygill-Walsh, R.; Suen, L.W.; Mohebbi, S.; Geier, M. Triple threat: Response to the crises of COVID-19, homelessness, and opioid use disorder with a novel approach to buprenorphine delivery: A case series. J. Addict. Med. 2022, 16, 733–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, Y.; Revell, Z.; Wilson, V.; Guan, T.H.; Lambert, J.; Saeed, S. Isolation to stabilization: A Housing First approach to address homelessness in Kingston, Ontario. Can. J. Public Health 2025, 116, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hollingdrake, O.; Grech, E.; Papas, L.; Currie, J. Implementing a COVID-19 vaccination outreach service for people experiencing homelessness. Health Promot. J. Aust. 2025, 36, e885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osman, I.; Sieving, R.; Vasilakos, L.; Pierson, K.; Elgonda, A.; Bartlett, T.; O’Brien, J.R.G. Promoting COVID-19 vaccine confidence and access among youth experiencing homelessness: Community-engaged public health practice. Prog. Community Health Partnersh. Res. Educ. Action 2024, 18, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, A.D.; Senturia, A.; Howerton, I.; Kantrim, E.U.; Evans, V.; Malluche, T.; Miller, J.; Gonzalez, M.; Robie, B.; Shover, C.L.; et al. A COVID-19 vaccination program to promote uptake and equity for people experiencing homelessness in Los Angeles County. Am. J. Public Health 2023, 113, 170–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Specht, A.; Sarma, N.; Linzbach, T.; Hellmund, T.; Hörig, M.; Wintel, M.; Martinez, G.E.; Seybold, J.; Lindner, A.K. Participatory development and implementation of inclusive digital health communication on COVID-19 with homeless people. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 1042677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yi, S.; Wiesmann, C.; Truong, D.; Sharma, S.; Conway, B. Harnessing the power of the community to increase vaccination among homeless populations in inner-city Vancouver. Future Virol. 2024, 19, 465–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Békási, S.; Girasek, E.; Győrffy, Z. Telemedicine in community shelters: Possibilities to improve chronic care among people experiencing homelessness in Hungary. Int. J. Equity Health 2022, 21, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meray, V.; Motorwala, A.; Sellers, K.P.; Suarez, A.; Schneider, G.W. Telehealth Monitoring for Individuals Experiencing Homelessness During the Early COVID-19 Pandemic: An Innovative Clinical and Medical Education Model. Cureus 2022, 14, e31528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baggett, T.P.; Racine, M.W.; Lewis, E.; De Las Nueces, D.; O’Connell, J.J.; Bock, B.; Gaeta, J.M. Addressing COVID-19 among people experiencing homelessness: Description, adaptation, and early findings of a multiagency response in Boston. Public Health Rep. 2020, 135, 435–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, A.J.; Halperin, D.M.; Condran, B.R.; Kervin, M.S.; Di Castri, A.M.; Salter, K.L.; Bettinger, J.A.; Parsons, J.A.; Halperin, S.A. Exploring the effects of COVID-19 outbreak control policies on services offered to people experiencing homelessness. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 2804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perri, M.; Dosani, N.; Hwang, S.W. COVID-19 and people experiencing homelessness: Challenges and mitigation strategies. Can. Med Assoc. J. 2020, 192, E716–E719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez, N.M.; Lahey, A.M.; MacNeill, J.J.; Martinez, R.G.; Teo, N.E.; Ruiz, Y. Homelessness during COVID-19: Challenges, responses, and lessons learned from homeless service providers in Tippecanoe County, Indiana. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benfer, E.A.; Vlahov, D.; Long, M.Y.; Walker-Wells, E.; Pottenger, J.L.; Gonsalves, G.; Keene, D.E. Correction to: Eviction, health inequity, and the spread of COVID-19: Housing policy as a primary pandemic mitigation strategy. J. Urban Health 2021, 98, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isabel, M.; Turgeon, D.; Lessard, É.; Panaite, A.C.; Ballu, G.; Desroches, O.A.; Rouly, G.; Boivin, A. From Disruption to Reconstruction: Implementing Peer Support in Homelessness During Times of Crisis for Health and Social Care Services. Int. J. Integr. Care 2025, 25, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komaromy, M.; Harris, M.; Koenig, R.M.; Tomanovich, M.; Ruiz-Mercado, G.; Barocas, J.A. Caring for COVID’s most vulnerable victims: A safety-net hospital responds. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2021, 36, 1006–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosecrans, A.M.; Moen, M.A.; Harris, R.E.; Rice, M.S.; Augustin, V.S.; Stracker, N.H.; Burns, K.D.; Rives, S.T.; Tran, K.M.; Callahan, C.W.; et al. Implementation of Baltimore City’s COVID-19 isolation hotel. Am. J. Public Health 2022, 112, 876–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.Y.; Palma, M.L.; Haley, C.; Watts, J.; Hinami, K. Rapid Creation of a Multiagency Alternate Care Site for COVID-19–Positive Individuals Experiencing Homelessness. Am. J. Public Health 2021, 111, 1227–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loutfy, M.; Kennedy, V.L.; Riazi, S.; Lena, S.; Kazemi, M.; Bawden, J.; Wright, V.; Richardson, L.; Mills, S.; Belsito, L.; et al. Development and assessment of a hospital-led, community-partnering COVID-19 testing and prevention program for homeless and congregate living services in Toronto, Canada: A descriptive feasibility study. Can. Med. Assoc. Open Access J. 2022, 10, E483–E490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gould, T.E.; Williams, A.R. Family homelessness: An investigation of structural effects. J. Hum. Behav. Soc. Environ. 2010, 20, 170–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadermann, A.M.; Hubley, A.M.; Russell, L.B.; Palepu, A. Subjective health-related quality of life in homeless and vulnerably housed individuals and its relationship with self-reported physical and mental health status. Soc. Indic. Res. 2014, 116, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connell, M.J.; Kasprow, W.J.; Rosenheck, R.A. The impact of current alcohol and drug use on outcomes among homeless veterans entering supported housing. Psychol. Serv. 2013, 10, 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López Bermúdez, A. Sinhogarismo: Concepción y abordaje desde el punto de vista de las/los trabajadoras/es sociales de Mallorca. Rev. Trab. Soc. Acción Soc. 2019, 62, 32–49. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/descarga/articulo/7639711.pdf (accessed on 4 May 2025).

- Corey, J.; Lyons, J.; O’Carroll, A.; Stafford, R.; Ivers, J.-H. A Scoping Review of the Health Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Persons Experiencing Homelessness in North America and Europe. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montgomery, M.P.; Paulin, H.N.; Morris, A.; Cotton, A.; Speers, A.; Boyd, A.T.; Buff, A.M.; Mathews, D.M.; Wells, A.; Marchman, C.; et al. Establishment of isolation and noncongregate hotels during COVID-19 and symptom evolution among people experiencing homelessness—Atlanta, Georgia, 2020. J. Public Health Manag. Pract. 2021, 27, 285–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akingbola, S.; Fernandes, R.; Borden, S.; Gilbride, K.; Oswald, C.; Straus, S.; Tehrani, A.; Thomas, J.; Stuart, R. Early identification of a COVID-19 outbreak detected by wastewater surveillance at a large homeless shelter in Toronto, Ontario. Can. J. Public Health 2023, 114, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aranda-Díaz, A.; Imbert, E.; Strieff, S.; Graham-Squire, D.; Evans, J.L.; Moore, J.; McFarland, W.; Fuchs, J.; Handley, M.A.; Kushel, M.; et al. Implementation of rapid and frequent SARS-CoV2 antigen testing and response in congregate homeless shelters. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0264929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahillan, T.; Emmerson, M.; Swift, B.; Golamgouse, H.; Song, K.; Roxas, A.; Mendha, S.B.; Avramović, E.; Rastogi, J.; Sultan, B. COVID-19 in the homeless population: A scoping review and meta-analysis examining differences in prevalence, presentation, vaccine hesitancy and government response in the first year of the pandemic. BMC Infect. Dis. 2023, 23, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Land, S.R.; Derrien, M.M. Homelessness and Nature across Landscapes and Disciplines: A Literature Review. Landscape and Urban Planning 2025, 255, 105254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, E.; Waring, T.; Ahern, E.; O’Donovan, D.; O’Reilly, D.; Bradley, D.T. Predictors and consequences of homelessness in whole-population observational studies that used administrative data: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, N.; Adams, E.A.; Haddow, K.; Brown, J.; Bleksley, D.; Morrison, S.; Kesten, J.; Howells, K.; Sanders, C.; Adamson, A.J.; et al. Learnings from providing integrated health, housing and wider care for people rough sleeping during the COVID-19 pandemic: A national qualitative study of the ‘Everyone In’ policy initiative. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2025, 25, 549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puig Domènech, A. Por Qué y Cómo se Hace la Ciencia: CSIC y Catarata. 2021. Available online: https://www.csic.es/es/ciencia-y-sociedad/libros-de-divulgacion/coleccion-que-sabemos-de/por-que-y-como-se-hace-la-ciencia (accessed on 4 May 2025).

- Lachaud, J.; Yusuf, A.A.; Maelzer, F.; Perri, M.; Gogosis, E.; Ziegler, C.; Mejia-Lancheros, C.; Hwang, S.W. Social isolation and loneliness among people living with experience of homelessness: A scoping review. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 2515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Melero-Fuentes, D.; Aguilar-Moya, R. Socio-Scientific Perspectives on COVID-Planned Interventions in the Homeless Population. Societies 2025, 15, 197. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15070197

Melero-Fuentes D, Aguilar-Moya R. Socio-Scientific Perspectives on COVID-Planned Interventions in the Homeless Population. Societies. 2025; 15(7):197. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15070197

Chicago/Turabian StyleMelero-Fuentes, David, and Remedios Aguilar-Moya. 2025. "Socio-Scientific Perspectives on COVID-Planned Interventions in the Homeless Population" Societies 15, no. 7: 197. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15070197

APA StyleMelero-Fuentes, D., & Aguilar-Moya, R. (2025). Socio-Scientific Perspectives on COVID-Planned Interventions in the Homeless Population. Societies, 15(7), 197. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15070197