The Social and Citizen Participation of Older People as a Factor for Social Inclusion: Determinants and Challenges According to a Technical Expert Panel

Abstract

1. Introduction

Objectives and Hypotheses

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Selection Criteria and Composition of the Technical Expert Panel

2.2. Dynamics of the Technical Expert Panel

3. Results

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bourassa, K.; Memel, M.; Woolverton, C.; Sbarra, D. Social participation predicts cognitive functioning in aging adults over time: Comparisons with physical health, depression, and physical activity. Aging Ment. Health 2017, 21, 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Douglas, H.; Georgiou, A.; Westbrook, J. Social participation as an indicator of successful aging: An overview of concepts and their associations with health. Aust. Health Rev. 2017, 41, 455–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santini, Z.; Jose, P.; Koyanagi, A.; Meilstrup, C.; Nielsen, L.; Madsen, K.; Koushede, V. Formal social participation protects physical health through enhanced mental health: A longitudinal mediation analysis using three consecutive waves of the survey of health, ageing and retirement in Europe (SHARE). Soc. Sci. Med. 2020, 251, 112906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sellon, A. The importance of meaningful participation: Health benefits of volunteerism for older people with mobility-limiting disabilities. Ageing Soc. 2021, 43, 878–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Townsend, B.; Chen, J.; Wuthrich, V. Barriers and facilitators to social participation in older people: A systematic literature review. Clin. Gerontol. 2021, 44, 359–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löfgren, M.; Larsson, E.; Isaksson, G.; Nyman, A. Older people’s experiences of maintaining social participation: Creating opportunities and striving to adapt to changing situations. Scand. J. Occup. Ther. 2022, 29, 587–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Yang, D.; Tian, Y. Enjoying the golden years: Social participation and life satisfaction among Chinese older people. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1377869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liougas, M.; Fortino, A.; Brozowski, K.; McMurray, J. Social inclusion programming for older people living in age-friendly cities: A scoping review. BMJ Open 2025, 15, e088439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baeriswyl, M.; Oris, M. Social participation and life satisfaction among older people: Diversity of practices and social inequality in Switzerland. Ageing Soc. 2021, 43, 1259–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ide, K.; Tsuji, T.; Kanamori, S.; Jeong, S.; Nagamine, Y.; Kondo, K. Participation and functional decline: A comparative study of rural and urban older people, using Japan gerontological evaluation study longitudinal data. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinazo, S.; Blanco, M.; Ortega, R. Aging in place: Connections, relationships, social participation and social support in the face of crisis situations. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newall, N.; Chipperfield, J.; Clifton, R.; Perry, R.; Swift, A.; Ruthig, J. Causal beliefs, social participation, and loneliness among older people: A longitudinal study. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 2009, 26, 273–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, T.; Kafková, M.P.; Katz, R.; Lowenstein, A.; Naim, S.; Pavlidis, G.; Villar, F.; Walsh, K.; Aartsen, M. Exclusion from social relations in late life: Micro- and macro-level patterns and correlations in a European perspective. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibáñez-del Valle, V.; Corchón, S.; Zaharia, G.; Cauli, O. Social and emotional loneliness in older community dwelling individuals: The role of socio-demographics. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Donder, L.; De Witte, N.; Buffel, T.; Dury, S.; Verté, D. Social capital and feelings of unsafety in later life: A study on the influence of social networks, place attachment and civic participation on perceived safety in Belgium. Res. Aging 2012, 34, 424–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Shek, D.; Du, W.; Pan, Y.; Ma, Y. The relationship between social participation and subjective well-being among older people in the Chinese culture context: The mediating effect of reciprocity beliefs. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehi, M.; Mohammadi, F. Social participation of older people: A concept analysis. IJCBNM 2020, 8, 55–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, K.; Leibbrandt, S.; Moon, H. A critical review of the literature on social and leisure activity and wellbeing in later life. Ageing Soc. 2011, 31, 683–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohli, M.; Hank, K.; Künemund, H. The social connectedness of older Europeans: Patterns, dynamics and contexts. J. Eur. Soc. Policy 2009, 19, 327–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levasseur, M.; Richard, L.; Gauvin, L.; Raymond, E. Inventory and analysis of definitions of social participation found in the aging literature: Proposed taxonomy of social activities. Soc. Sci. Med. 2010, 71, 2141–2149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Cabrero, G.; Rodríguez-Rodríguez, P.; Castejón, P.; Morán, E. Las Personas Mayores que Vienen. Autonomía, Solidaridad y Participación Social; Estudios de la Fundación Pilares: Madrid, Spain, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Pinazo, S.; Torregrosa, M.; Jimenez, M.; Blanco, M. Participación social y satisfacción vital: Diferencias entre mujeres y hombres. Rev. Psicol. Salud (New Age) 2019, 7, 202–234. [Google Scholar]

- Dizon, L.; Wiles, J.; Peiris-John, R. What is meaningful participation for older people? An analysis of aging policies. Gerontologist 2020, 60, 396–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, M. Inclusion, Social Inclusion and Participation. In Critical Perspectives on Human Rights and Disability Law, 1st ed.; Rioux, M., Basser, L., Jones, M., Eds.; Brill|Nijhoff: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hauke, B. Social participation and cohesion. On the relationship between “inclusion” and “integration” in social theory. Soc. Theory Pract. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Warburton, J.; Hung, S.; Shardlow, S. Social inclusion in an ageing world: Introduction to the special issue. Ageing Soc. 2013, 33, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merino, A.; Di Giusto, C.; Sáez, S. Social Inclusion in Cultural Participation: A Systematic Review; Universidad de Burgos: Burgos, Spain, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juma, F.; Fernández-Sainz, A. Social Exclusion Among Older People: A Multilevel Analysis for 10 European Countries. Soc. Indic. Res. 2024, 174, 525–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwachi, L. Relationship between Participation and Social Inclusion. Open J. Soc. Sci. 2021, 9, 46–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hocking, C.; Wright, V. Editorial: Special issue on inclusion and participation. J. Occup. Sci. 2017, 24, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdía, V. Participatory citizenship initiatives as a crucial factor for social cohesion. In Galician Migrations: A Case Study of Emerging Super-Diversity. Migration, Minorities and Modernity; De-Palma, R., Pérez-Caramés, A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulsen, T.; Christensen, U.; Lund, R.; Avlund, K. Measuring aspects of social capital in a gerontological perspective. Eur. J. Ageing 2011, 8, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera, M.; Fernández, M.; Elgueta, R. Social capital, social participation and life satisfaction among Chilean older people. Rev. Saúde Pública 2014, 48, 739–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiittanen, U.; Turjamaa, R. Social inclusion and communality of volunteering: A focus group study of older people’s experiences. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolrych, R.; Sixsmith, J.; Fisher, J.; Makita, M.; Lawthom, R.; Murray, M. Constructing and negotiating social participation in old age: Experiences of older people living in urban environments in the United Kingdom. Ageing Soc. 2021, 41, 1398–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadei, L.; Deluigi, R. Inclusion through participation: Approaches, strategies and methods. Educ. Sci. Soc. 2016, 1/2016, 82–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hintjens, H.; Kurian, R. Enacting citizenship and the right to the city: Towards inclusion through deepening democracy? Soc. Incl. 2019, 7, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. World Report on Ageing and Health; World Health Organization: Luxembourg, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Klimczuk, A. Comparative analysis of national and regional models of the silver economy in the European Union. Int. J. Ageing Later Life 2016, 10, 31–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogelj, V.; Bogataj, D. Social infrastructure of silver economy: Literature review and research agenda. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2019, 52, 2680–2685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Rodríguez, P. La atención integral y centrada en la persona (AICP) en el ámbito de los cuidados de larga duración. Sus fundamentos y sus dos dimensiones. In La Atención Integral y Centrada en la Persona. Fundamentos y Aplicaciones en el Modelo de Apoyos y Cuidados; Rodríguez-Rodríguez, P., Vilà, A., Ramos, C., Eds.; Tecnos: Madrid, Spain, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Tronto, J. Caring Democracy: Markets, Equality and Justice; NYU Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Global Age-Friendly Cities: A Guide; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Buffel, T.; De Donder, L.; Phillipson, C.; Dury, S.; De Witte, N.; Verté, D. Social participation among older people living in medium-sized cities in Belgium: The role of neighbourhood perceptions. Health Promot. Int. 2014, 29, 655–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard, L.; Gauvin, L.; Gosselin, C.; Laforest, S. Staying connected: Neighbourhood correlates of social participation among older people living in an urban environment in Montreal, Quebec. Health Promot. Int. 2009, 24, 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Porrero, C.; García-Milà, X. Diseño universal, accesibilidad en viviendas, tecnologías y servicios de apoyo. In La Atención Integral y Centrada en la Persona. Fundamentos y Aplicaciones en el Modelo de Apoyos y Cuidados; Rodríguez, P., Vilà, A., Ramos, C., Eds.; Tecnos: Madrid, Spain, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Frank, E. Habitar la Vejez. Dependencia.info. 2023. Available online: https://dependencia.info/noticia/5437/arquitectura-y-residencias/arquitectura-y-residencias:-habitar-la-vejez-habitar-la-ciudad-por-eduardo-frank-vi.html (accessed on 6 April 2025).

- Treviranus, J.; Mitchell, J.; Clark, C.; Roberts, V. An introduction to the FLOE project. In Universal Access in Human-Computer Interaction. Universal Access to Information and Knowledge; Stephanidis, C., Antona, M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Teele, J. Measures of social participation. Soc. Probl. 1962, 10, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, R. Measuring social participation. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1983, 48, 864–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymond, E.; Sévigny, A.; Tourigny, A.; Vézina, A.; Verreault, R.; Guilbert, A. On the track of evaluated programmes targeting the social participation of seniors: A typology proposal. Ageing Soc. 2013, 33, 267–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, Z.; Madans, J.; Mont, D. Measuring the Autonomy, Participation and Contribution of Older People; Paper Prepared for Programme and Ageing Unit; Social Inclusion and Participation Branch, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Alberich, T.; Espadas, A. Asociacionismo, participación ciudadana y políticas locales: Planteamiento teórico y una experiencia práctica en Jaén. Altern. Cuad. De Trab. Soc. 2011, 18, 119–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levasseur, M.; Lussier-Therrien, M.; Biron, M.; Raymond, É.; Castonguay, N.; Naud, D.; Fortier, M.; Sévigny, A.; Houde, S.; Tremblay, L. Scoping study of definitions of social participation: Update and co-construction of an interdisciplinary consensual definition. Ageing Soc. 2022, 51, afab215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alberich, T.; Espadas, A. Democracia, participación ciudadana y funciones del trabajo social. Trab. Soc. Glob. 2014, 4, 3–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falanga, R.; Cebulla, A.; Principi, A.; Socci, M. The participation of senior citizens in policymaking: Patterning initiatives in Europe. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, D.; Castillo, J.; Sandoval, A. Young citizens participation: Empirical testing of a conceptual model. Youth Soc. 2020, 52, 251–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bracht, N.; Tsouros, A. Principles and strategies of effective community participation. Health Promot. Int. 1990, 5, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, M.; Dillman, D. Community participation, social ties, and use of the internet. City Community 2006, 5, 409–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, F.; Bush, R.; Modra, C.; Murray, C.; Cox, E.; Alexander, K.; Potter, R. Epidemiology of participation: An Australian community study. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2000, 54, 414–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgkin, S. I’m older and more interested in my community: Older people’s contributions to social capital. Australas. J. Ageing 2012, 31, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicognani, E.; Mazzoni, D.; Albanesi, C.; Zani, B. Sense of community and empowerment among young people: Understanding pathways from civic participation to social well-being. Voluntas 2014, 26, 24–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manthorpe, J.; Harris, J.; Mauger, S. Older people’s forums in the United Kingdom: Civic engagement and activism reviewed. Work. Older People 2016, 20, 165–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glidden, R.; Borges, C.; Pianezer, A.; Martins, J. La participación de las personas de la tercera edad en grupos de personas mayores y su relación de satisfacción con el apoyo social y el optimismo. Boletín-Acad. Paul. Psicol. 2019, 39, 261–275. [Google Scholar]

- Goerres, A. Why are older people more likely to vote? The impact of ageing on electoral turnout in Europe. Br. J. Politics Int. Relat. 2007, 9, 90–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goerres, A. The Political Participation of Older People in Europe. The Greying of Our Democracies; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Quinzán, S.; Groba, D.; Martínez, P. La dimensión política del envejecimiento activo: Personas mayores y participación política. Aposta: Rev. Cienc. Soc. 2022, 92, 87–105. [Google Scholar]

- Waggoner, J.; Carline, J.D.; Durning, S.J. Is there a consensus on consensus methodology? Descriptions and recommendations for future consensus research. Acad. Med. 2016, 91, 663–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Collado, A. Elementos esenciales para elaborar un estudio con el método (e)Delphi. Enfermería Intensiv. 2021, 32, 100–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilà-Mancebo, T. El nuevo paradigma legislativo y su relación con el modelo AICP. In La Atención Integral y Centrada en la Persona. Fundamentos y Aplicaciones en el Modelo de Apoyos y Cuidados; Rodríguez-Rodríguez, P., Vilà, A., Ramos, C., Eds.; Tecnos: Madrid, Spain, 2022. [Google Scholar]

| Tags/Domains | Dimensions | Characteristics | Examples of Inclusive Participation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Citizen participation Active participation Civic participation (linked to the notion of participation in public affairs) | POLITICAL AND ELECTORAL PARTICIPATION | Participating in political parties, voting, demonstrations, protests, etc. | Political party militancy, attending demonstrations, voting in elections, signing petitions |

| ACTIVE CITIZENSHIP AND CIVIC ENGAGEMENT | Expressing opinions on public affairs, public engagements, involvement in participatory democracy events, institutional decision-making, etc. | Participation in community workshops, participation in institutional participation processes, contacting politicians or officials | |

| Social participation Community involvement Nominal participation (linked to the generation of community capital) | ASSOCIATIONS AND VOLUNTEERING | Membership of organisations, participation in association activities, volunteer work, etc. | Being a member of associations, volunteering, participating in activities organised by associations |

| PUBLIC SOCIABILITY | Unorganised interaction in group contexts outside the private sphere, informal coexistence activities, etc. | Talking to people in the neighbourhood, attending a public event, attending a show, etc. |

| Problems Identified in the Participation of Older People | |||

|---|---|---|---|

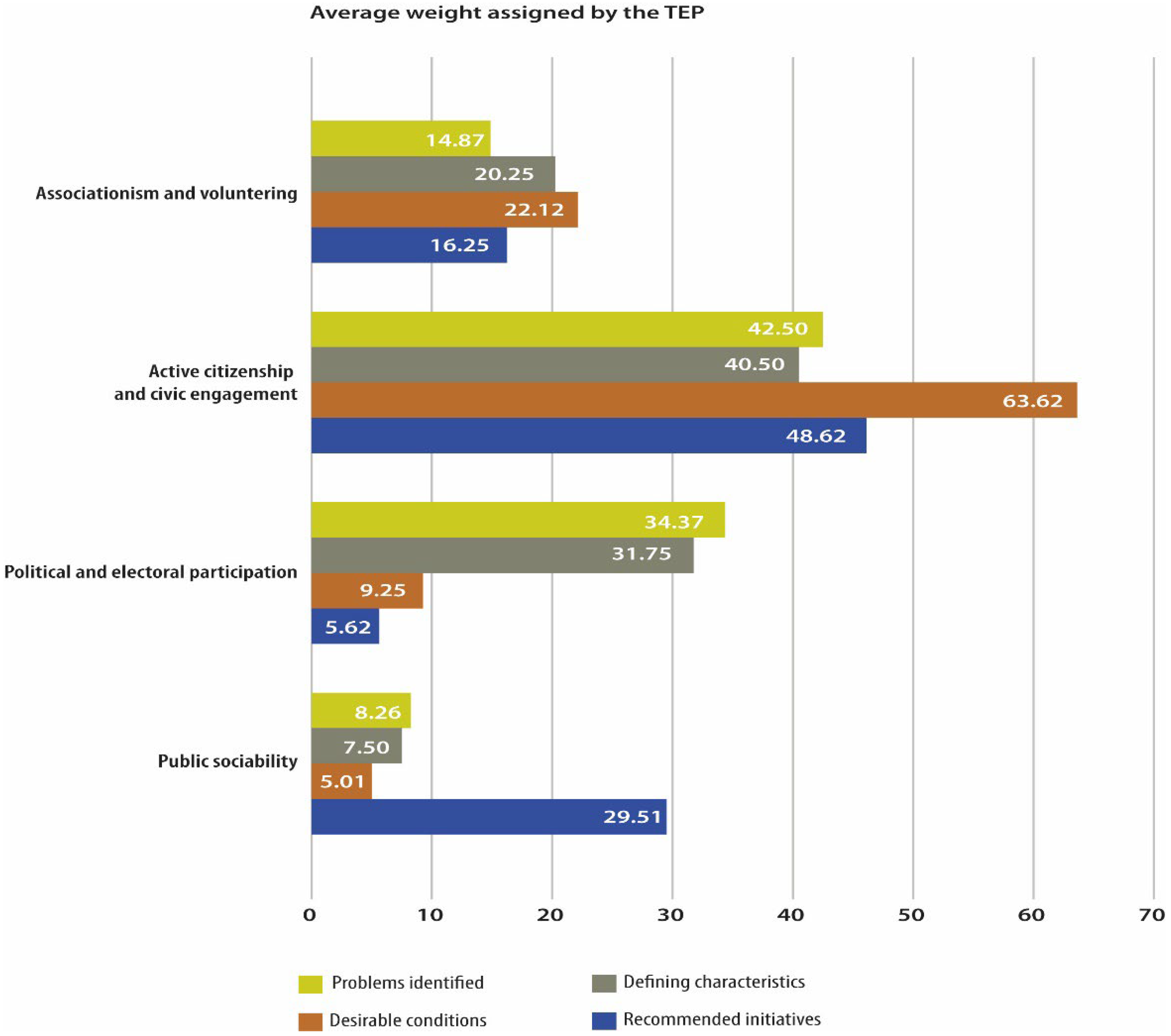

| Dimension | No. of Identified Challenges | Average Score of Challenges in Each Dimension | SD |

| Associations and volunteering | 7 | 14.87 | 5.86 |

| Active citizenship and civic engagement | 16 | 42.50 | 14.82 |

| Political and electoral participation | 11 | 34.37 | 13.30 |

| Public sociability | 6 | 8.26 | 5.06 |

| TOTAL | 40 | 100.00 | |

| Defining Characteristics of the Participation of Older People | |||

| Dimension | No. of Identified Challenges | Average Score for Challenges in Each Dimension | SD |

| Associations and volunteering | 6 | 20.25 | 6.56 |

| Active citizenship and civic engagement | 11 | 40.50 | 12.25 |

| Political and electoral participation | 9 | 31.75 | 12.27 |

| Public sociability | 6 | 7.50 | 7.07 |

| TOTAL | 32 | 100.00 | |

| Desirable Conditions for the Participation of Older People | |||

| Dimension | No. of Identified Challenges | Average Score for Challenges in Each Dimension | SD |

| Associations and volunteering | 8 | 22.12 | 12.75 |

| Active citizenship and civic engagement | 20 | 63.62 | 10.94 |

| Political and electoral participation | 4 | 9.25 | 4.68 |

| Public sociability | 6 | 5.01 | 8.00 |

| TOTAL | 38 | 100.00 | |

| Recommended Initiatives for the Participation of Older People | |||

| Dimension | No. of Identified Challenges | Average Score for Challenges in Each Dimension | SD |

| Associations and volunteering | 9 | 16.25 | 9.73 |

| Active citizenship and civic engagement | 13 | 48.62 | 9.02 |

| Political and electoral participation | 7 | 5.62 | 6.43 |

| Public sociability | 9 | 29.51 | 11.23 |

| TOTAL | 100.00 | ||

| Analytical Lines | Challenges Identified by Experts | DIMENSION | Percent Panel Agreement | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Associations and Volunteering | Political and Electoral Participation | Active Citizenship and Civic Engagement | Public Sociability | |||

| Problems identified | Lack of community vision of political representatives regarding the participation of older people | X | 87.5% | |||

| Very individualistic society with little appreciation of the community, which prevents active engagement | X | 62.5% | ||||

| Digital divide in some segments of the older people population of access to certain mechanisms of political participation | X | 62.5% | ||||

| Defining characteristics | Lack of awareness of the potential of the older people, who are regarded as passive consumers | X | 87.5% | |||

| Institutional participation bodies have a consultative nature with little impact on political agendas | X | 87.5% | ||||

| Little renewal in the leading positions of the groups of older people, which hinders the regeneration of associations | X | 75.0% | ||||

| Political parties are interested in the older people segment of the population only in electoral periods | X | 62.5% | ||||

| Desirable conditions | Going beyond the consultative nature of most domains linked to the participation of the older people, seeking more effective participation | X | 75.0% | |||

| Greater role of older people in the design of programmes and policies, not only as recipients | X | 75.0% | ||||

| Take advantage of the political capital deriving from the life experience and knowledge of older people | X | 62.5% | ||||

| Elimination of stereotypes, myths, or social prejudices regarding ageing and older people | X | 62.5% | ||||

| Design of public policies based on person-centred and appropriate care for an ageing society | X | 62.5% | ||||

| Recommended initiatives | Act on homes that generate isolation and create new housing solutions that favour coexistence | X | 75.0% | |||

| Find new formulas or mechanisms for the participation of older people that differ from traditional solutions | X | 62.5% | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Francés-García, F.; Ramos-Feijóo, C.; Lillo-Beneyto, A. The Social and Citizen Participation of Older People as a Factor for Social Inclusion: Determinants and Challenges According to a Technical Expert Panel. Societies 2025, 15, 185. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15070185

Francés-García F, Ramos-Feijóo C, Lillo-Beneyto A. The Social and Citizen Participation of Older People as a Factor for Social Inclusion: Determinants and Challenges According to a Technical Expert Panel. Societies. 2025; 15(7):185. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15070185

Chicago/Turabian StyleFrancés-García, Francisco, Clarisa Ramos-Feijóo, and Asunción Lillo-Beneyto. 2025. "The Social and Citizen Participation of Older People as a Factor for Social Inclusion: Determinants and Challenges According to a Technical Expert Panel" Societies 15, no. 7: 185. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15070185

APA StyleFrancés-García, F., Ramos-Feijóo, C., & Lillo-Beneyto, A. (2025). The Social and Citizen Participation of Older People as a Factor for Social Inclusion: Determinants and Challenges According to a Technical Expert Panel. Societies, 15(7), 185. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15070185