Abstract

This study addresses the persistent issue of gender bias in project management by developing and validating a practical survey tool for monitoring gender-related perceptions within project implementation frameworks. Using a Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices (KAP) approach, a survey instrument was designed to assess awareness of gender equity policies, perceptions of inclusivity, and experiences related to sexual harassment (SASH) within project teams. The tool was piloted in a Horizon Europe project (Healthy Sailing), with responses collected from 66 participants (academics, maritime professionals, researchers, and government stakeholders). Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) revealed a five-factor structure explaining 72.29% of total variance, with the two dominant factors—Perceived Gender Bias and Organizational Safety—demonstrating excellent internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha > 0.90). Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) and bifactor modeling indicated areas for further refinement, with RMSEA values exceeding optimal thresholds. The results underscore the potential of the KAP-based tool to support gender-sensitive quality management practices in project-based environments, while highlighting the need for ongoing psychometric validation. The study contributes a novel, empirically grounded instrument for promoting inclusivity and equity in project management.

1. Introduction

Despite project management being one of the fastest-growing professions globally, with over 90 million individuals expected to work in project-based roles by 2030, gender inequality remains a structural reality. Women make up nearly half of the global workforce, yet they continue to be underrepresented in senior project leadership roles, particularly in industries like construction, IT, and engineering [1]. Their journeys through project hierarchies are often punctuated by bias, exclusion, and invisible ceilings. Studying gender in project management is not just a matter of representation; it is a matter of performance, ethics, and sustainability. Projects shape infrastructure, technology, healthcare systems, and public services; they are the engines of societal transformation. When leadership structures within these projects exclude or undervalue half the population, the outcomes reflect a narrow, incomplete perspective. Moreover, projects are inherently human enterprises. They require negotiation, empathy, conflict resolution, and cultural intelligence—all competencies where research consistently shows that women often excel [2,3]. Yet, women continue to be less likely to be assigned high-visibility, strategic projects, a phenomenon sometimes referred to as the “glass wall”, keeping women in support roles rather than leadership pipelines [4]. By studying gender disparities in project environments, we gain more than data; we unearth a cultural blueprint of how power is distributed, how success is measured, and whose voices get amplified in moments of crisis or innovation. Women, according to multiple studies, tend to lead with transformational, participatory, and emotionally intelligent styles—skills linked to higher project team morale and stakeholder satisfaction [5,6]. Organizations that recognize and empower female project leaders outperform on key performance indicators, including project ROI, employee engagement, and innovation scores [1]. Yet, despite these gains, the gender gap remains wide, especially at the program and portfolio management levels.

Moreover, project management has rapidly evolved from a technical coordination role into a complex, multidisciplinary leadership function. As organizations worldwide increasingly depend on projects for strategic growth, the competencies of project managers have expanded to include not only technical expertise but also emotional intelligence, stakeholder negotiation, and inclusive decision-making [3,6]. However, despite these shifts, gender disparities persist, particularly in leadership roles within the project management profession. The historical underrepresentation of women in project management is not merely a numerical imbalance; it reflects broader social structures, organizational cultures, and leadership expectations rooted in masculine norms [7]. While female representation has grown over the past two decades, especially in sectors like healthcare and education, women continue to face barriers in high-tech and engineering-based project environments [8].

In response to these challenges, several organizations and institutions have introduced diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) strategies to foster women’s advancement in project management. Professional bodies such as the Project Management Institute (PMI) have published gender-specific research and launched initiatives like Women in Project Management (WiPM) chapters globally [5]. Moreover, companies that implement gender-sensitive project allocation and leadership training programs show higher levels of innovation and project performance [1] (Governments in the EU, Canada, and Australia have also mandated gender quotas in public procurement and infrastructure projects, forcing a rethink of traditional leadership structures.

While macro-level studies have identified broad gender trends in management, there remains a lack of micro-level, survey-based research specifically addressing the experiences, perceptions, and career trajectories of women in project management roles. This research aims to open a broader investigation, anchored in a survey-based study, seeking to explore the lived experiences of women in project management. The research focuses on several critical questions regarding the obstacles women face in accessing project leadership opportunities and how organizational cultures support or hinder gender equity in project assignments. By quantifying and contextualizing these questions, this research aims not only to contribute to academic discourse but also to provide evidence-based recommendations for employers, industry bodies, and educators committed to dismantling gender barriers.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. Section 2 presents a comprehensive literature review and highlights the existing research gaps on gender aspects in project management. Section 3 introduces the research framework, including the relevant policy background and alignment with prior studies. Section 4 describes the research methodology and details the development and structure of the survey instrument. Section 5 reports on the validation of the measurement tool, including exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses. Section 6 presents the findings of the pilot case study conducted within the Healthy Sailing Project. Finally, Section 7 summarizes the key conclusions, discusses practical implications, and outlines directions for future research.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Gender Issues in Project Management

Extensive literature supports the notion that women bring distinctive leadership strengths to project environments, with studies often describing women as more transformational, collaborative, and communicative compared to their male counterparts [2,3]. These traits have been increasingly associated with project success, especially in dynamic, cross-functional, and team-based settings. For instance, Müller and Turner found that projects led by transformational leaders—many of whom were women—demonstrated higher stakeholder satisfaction [3]. Moreover, women project managers tend to emphasize inclusive communication, risk aversion, and ethical governance, attributes increasingly valued in agile, stakeholder-centric project paradigms [5]. Despite these strengths, women in project management face a range of systemic barriers that limit their upward mobility and influence, including:

- Gender stereotyping: women are often perceived as less competent in technical or high-risk projects [9];

- Glass ceiling and sticky floors: many women remain in junior roles due to lack of mentorship or organizational bias [8];

- Work-life conflict: project deadlines, travel requirements, and irregular hours often conflict with social expectations around caregiving [10].

Additionally, there is evidence that women are less likely to be assigned strategic projects, the very assignments that provide visibility and career advancement opportunities [4].

The intersection of gender and project management is a burgeoning field of research, exploring the unique challenges, opportunities, and contributions that women bring to project-based work [11,12]. Although project management has evolved significantly, women continue to be underrepresented, especially in leadership roles. According to the Project Management Institute, only 29% of project managers globally are women, and even fewer occupy executive-level positions [13,14]. This gap is attributed to systemic barriers such as gendered organizational cultures, lack of mentorship, and limited access to strategic assignments [13,15]. Buckle and Thomas highlight that leadership in project environments often defaults to masculine norms, valuing assertiveness over collaboration, traits stereotypically not associated with female leadership [16]. Moreover, recent findings indicate that gender bias affects not only hiring and promotions but also performance evaluations [1]

To address these issues, Kitada and Langåker recommend embedding gender mainstreaming into institutional policy, while other authors argue for gender-sensitive leadership training [17]. The need for culturally contextual strategies is emphasized in Quinteros, who finds that gender dynamics vary widely across regions and sectors, particularly in international or EU-funded projects where diversity is legally mandated but inconsistently practiced [18,19].

2.2. Key Themes in Prior Research

The literature review revealed the following key themes in existing knowledge on the gender subject [16,17,18,19,20]:

- Underrepresentation of women in project management:

- Statistical evidence: studies consistently point to a gender imbalance in project management roles, with women often occupying lower-level positions or being underrepresented in leadership roles;

- The contributing factors for this under-representation are stereotypes, biases, and systemic barriers that can hinder women’s advancement in the field.

- Gendered stereotypes and biases:

- Traditional masculine norms: the project management profession has historically been associated with masculine traits like assertiveness, decisiveness, and risk-taking and these stereotypes can disadvantage women who may be perceived as less suitable for leadership roles;

- Implicit bias refers to the unconscious biases that can influence hiring, promotion, and evaluation decisions, leading to discriminatory practices against women.

- Challenges faced by women project managers:

- Work-life balance: women often bear a disproportionate share of domestic responsibilities, making it difficult to balance work imperatives and personal life variables, and this aspect can hinder their career progression and limit their opportunities for advancement;

- Glass ceiling—many women in project management encounter a “glass ceiling”, where they face invisible barriers that prevent them from reaching higher-level positions;

- Gendered language and communication styles—the use of gendered language and communication styles can create a hostile work environment for women.

- Contributions of women to project management:

- Diverse perspectives: women bring unique perspectives and problem-solving approaches to project management, which can enhance team effectiveness and project outcomes;

- Empathy and collaboration: women are often perceived as more empathetic and collaborative leaders, which can foster positive team dynamics and improve project success.

- Strategies for promoting gender equality in project management:

- Diversity and inclusion initiatives: organizations can implement policies and programs to promote gender diversity and inclusion in project management;

- Mentorship and sponsorship—mentorship programs can provide women with guidance, support, and opportunities for professional development;

- Flexible work arrangements—offering flexible work arrangements, such as remote work or flexible hours, can help women balance their work and personal responsibilities.

The key themes in gender analysis within project implementation literature include “gender-sensitive evaluation frameworks”, “integration of gender perspectives in project design”, and “addressing power dynamics in gender relations”. These themes highlight the importance of developing comprehensive evaluation methods, ensuring gender considerations are embedded in project planning, and recognizing the influence of power structures on gender equity [21].

2.3. Limitations in Existing Approaches

Despite the growing body of research on gender aspects in project management, several areas remain understudied or with uncertain influence regarding the effective insertion of gender-balanced policies within project implementation frameworks [12,14,20]. Following the research results and literature review conclusions [11,20], the authors have identified the following research gaps and potential research topics for future focus:

- Specialized studies are very relevant to be conducted on a larger scale under a quantitative analysis perspective to provide more robust evidence of gender disparities in project management [12];

- Cross-cultural comparisons are important to reveal how gender dynamics in project management vary across different cultural contexts, with a special focus on European Union-funded projects [22] (EU Union of Equality report “2023 Report of Gender Equality in European Union”);

- Examining the intersection of gender with other factors, such as race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status, would be very valuable in order to promote understanding of the complex experiences of marginalized groups [23];

- The impact of gender diversity on project outcomes calls for investigating the relationship between gender diversity in project teams and project success [24].

The literature on gender aspects in project management highlights the significant challenges faced by women in this field. By addressing these challenges and promoting gender equality, organizations can create more inclusive and equitable workplaces that benefit everyone [25]. Future research will be essential for deepening our understanding of these issues and developing effective strategies for change [26].

2.4. Research Gap and Contribution

In summary, the literature on gender analysis within project implementation emphasizes the necessity of gender-sensitive evaluation frameworks, the integration of gender perspectives in project design, and the critical examination of power dynamics affecting gender relations. These themes collectively underscore the importance of a holistic approach to gender equity in project implementation, ensuring that interventions are effective and inclusive.

In this context, the authors have identified the importance of a practical tool that would help project managers assess, during project implementation, the gender policy and diversity management effectiveness, supporting the implementation of a concluding output of the project consisting of a gender analysis report as a quality management indicator to be considered and ongoing reported.

3. Research Framework

3.1. Policy Framework

As stated in the “Union of Equality: EU gender equality strategy 2020–2025” enforced by COM (2020)/152/5.3.20, “…working together, we can make real progress achieving a Europe where women and men, girls and boys, in all their diversity, are equal—where they are free to pursue their chosen path in life and reach their full potential, where they have equal opportunities to thrive, and where they can equally participate in and lead our European society” [27]. In this spirit of community gender statement, the EU has made significant progress in gender equality policy settlement over the last decades, promoting equal treatment legislation, gender mainstreaming, the integration of the gender perspective into all other policies, and specific measures for the balanced and fair advancement of women in social, cultural, and economic frames. The EU Gender Equality Strategy 2020–2025 delivers the Commission’s commitment to achieving a Union of Equality. This strategy outlines policy objectives and actions aimed at fostering a gender-equal Europe—a Union where individuals, regardless of gender, can freely pursue their chosen paths in life, have equal opportunities to succeed, and can equally participate in and lead European society [27].

Depicting this framework, the key objectives toward the gender agenda achievement would include combatting gender-based violence, overcoming gender stereotypes, closing gender gaps in the labour market, ensuring equal participation across various sectors of the economy, and addressing gender-based payment disparities. The European Union strategy aims at a dual approach of gender mainstreaming combined with targeted actions, with intersectionality serving as a horizontal principle for its implementation (COM (2020)/152/5.3.20: Union of Equality: EU gender equality strategy 2020–2025) [27].

As a research methodology, the authors pursued a wide study of the European Union gender legal framework, and the major identified references that were considered in the present study and further in the gender survey tool design are the following community deeds and provisions (see the references, *legal framework):

- “Union of Equality: EU gender equality strategy 2020–2025” COM (2020)/152/5.3.20 [27];

- Directive 2002/73/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23.09 2002 amending Council Directive 76/207/EEC on the implementation of the principle of equal treatment for men and women as regards access to employment, vocational training, and promotion, and working [28];

- Directive 2006/54/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 5.07.2006 on the implementation of the principle of equal opportunities and equal treatment of men and women in matters of employment and occupation (recast), 2006, OJ L 209/23 [29];

- EU Charter of Fundamental Rights (i.e., Articles 21 and 23) [30];

- EU Union of Equality reports—“2023 Report of Gender Equality in European Union” [22];

- Directive (EU) 2019/1158 on work-life balance for parents and carers;

- EU Strategic Approach to Women, Peace and Security (WPS) annexed to the Foreign Affairs Council Conclusions on WPS adopted on 10 December 2018, (Council document 15086/18) (https://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/37412/st15086-en18.pdf, accessed on 1 March 2025) [31];

- EU Action Plan on Women, Peace and Security (WPS) 2019–2024/4 July 2019 EEAS (2019) 747 [32];

- United Nations—Sustainable Development Goals, Goal 5: Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls (https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/gender-equality, accessed on 1 March 2025) [33].

Therefore, considering the European Union imperatives and foreseen balanced gender policies and aiming at the survey outlines development, the gender analysis objectives considered by the authors in the present study were the following:

- Specific provisions are very relevant and highly recommended to be inserted in the project quality management plan for ongoing non-discrimination monitoring and gender balance analysis as required tools in achieving diversity management equity;

- In line with enhancing feasible tools for project implementation, KAP surveys are recommended to be applied to all project stakeholders during project implementation or during organized events and activities in order to identify the gender non-discrimination policies among project team members and researchers;

- The gender policy monitored through specific tools will permit the ongoing evaluation of Sexual Assault and Sexual Harassment (SASH) Policy implementation in the project implementation framework and consequently will facilitate the timely identification of potential illegal events on this matter;

- The quality management tools will facilitate the study of gender impact on project team member behaviour and personal performance assessment for improving human resources effectiveness toward an improved range of results’ quality;

- Applying a survey on project team members’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices will enhance awareness regarding gender relevance in regard to procedure implementations, biases and risky behaviour assessment;

- Finally, concluding scientific study regarding gender-based differences in behaviours and risky behaviour could be effectively observed, overcome and reported.

3.2. Alignment with Previous Research

This study seeks to offer a pioneering approach to addressing gender bias and inclusivity within project implementation frameworks by introducing a KAP-based survey instrument specifically validated within an EU-funded project context. The study findings both reinforce and extend the existing literature on gender disparities in project environments, while providing a concrete, scalable tool for real-time monitoring of gender-related attitudes and practices.

The outcomes of the developed survey echo a well-established body of literature asserting that women in project management face persistent structural barriers, including bias in task allocation, limited access to strategic roles, and subtle forms of workplace discrimination [1,8,9]. For example, the presence of undecided or ambivalent responses concerning harassment and task fairness suggests the existence of latent biases and unclear institutional communication, a finding consistent with previous studies that describe underreporting of gendered incidents [12,19].

The gendered perception gap, particularly visible in attitudes toward pay equity and promotion opportunities, parallels research by Turner and Buckle and Thomas, who note how male professionals often underestimate the prevalence or impact of gender bias in the workplace [15,16]. The study findings reinforce the “perception disconnect” whereby men report more optimism about gender equity than their female counterparts, a well-documented barrier to advancing institutional change.

While much of the existing research has relied on broad statistical overviews or qualitative interviews the present study advances the field by operationalizing a survey-based monitoring tool grounded in the KAP (Knowledge, Attitudes, Practices) framework [17]. The KAP model allows for real-time, empirical analysis of gender-related behaviors and perceptions at multiple levels of a project—a novel methodological advancement for both academia and practitioners. Importantly, this is among the first studies to integrate SASH (Sexual Assault and Sexual Harassment) policy awareness into a project quality management framework, aligning operational compliance with ethical and performance-oriented goals, this aspect being rarely addressed in earlier gender-mainstreaming tools.

Although the EU Gender Equality Strategy 2020–2025 mandates inclusive practices in publicly funded projects, our study confirms earlier critiques (e.g., [21]) that show a disconnect between institutional mandates and workplace reality. By embedding gender monitoring into the quality assurance process, this tool may bridge this gap, offering measurable, ongoing diagnostics rather than post-hoc audits or compliance reports.

3.3. Research Objectives

This study aims to develop, implement, and validate a gender-sensitive survey tool, based on the KAP framework, to be embedded in project quality management systems. The focus is to assess the effectiveness of gender policy integration and identify latent gender biases within project implementation frameworks, particularly in EU-funded initiatives. By operationalizing gender equity principles into a measurable tool, the study responds to the identified gap between theoretical gender mainstreaming mandates and practical organizational practices, thereby contributing to both academic research and applied project governance.

To support the overarching aim, this study pursues the following specific objectives:

- to design a gender bias assessment tool based on the KAP framework, tailored for project implementation contexts, incorporating indicators linked to knowledge of EU gender policies, individual attitudes toward inclusivity, and practices surrounding equality, harassment, and leadership dynamics;

- to explore perceptions of gender equity among project stakeholders, including academics, maritime professionals, researchers, and authorities, in the context of team communication, task distribution, leadership representation, and SASH (Sexual Assault and Sexual Harassment) policies;

- to validate the survey tool through a case study involving the Healthy Sailing Horizon Europe project, assessing its reliability and applicability within a real-world consortium working across diverse professional and cultural domains;

- to analyze demographic and experiential factors (such as gender, experience level, or occupational background) that influence awareness and practices related to gender equity in project environments;

- to align the instrument’s analytical framework with EU directives and policy priorities;

- to contribute empirically to the ongoing development of gender-sensitive quality management tools in project governance, promoting institutional transparency, ethical project delivery, and stakeholder engagement in line with European Commission mandates.

4. Research Method

4.1. Theoretical Frameworks Supporting the Survey Design

Despite increasing attention to gender equity in policy discourse and organizational management, the practical integration of gender perspectives within project implementation frameworks remains limited and uneven. This is especially true in sectors that are historically male-dominated, such as engineering, maritime industries, and research consortia, where diversity management is often reduced to compliance-based indicators rather than embedded cultural change [34,35]. Research consistently shows that gender biases persist in team dynamics, leadership evaluations, and promotional opportunities, even in high-skilled environments such as EU-funded research and innovation projects [12,19]. Moreover, female professionals often face disproportionate challenges including exclusion from decision-making circles, undervaluation of their contributions, and lack of visibility in project leadership roles [1,26].

While gender equality policies are mandated by major funding bodies like the European Commission under frameworks such as Horizon Europe and the EU Gender Equality Strategy 2020–2025, there is a notable gap in operational instruments that can effectively monitor, measure, and guide gender policy implementation at the project level [27]. Existing project quality management systems rarely include targeted tools to assess gender attitudes, workplace practices, or team member perceptions, leaving a disconnect between policy and practice [21].

In response to this gap, the present study introduces a KAP-based (Knowledge, Attitude, Practice) survey tool specifically designed to be embedded within the quality management framework of EU-funded projects. This instrument seeks to offer project managers and stakeholders a practical method for evaluating the level of gender awareness, equity practices, and the effectiveness of Sexual Assault and Sexual Harassment (SASH) policies throughout the project lifecycle. Through a pilot case study implemented in the “Healthy Sailing” Horizon EU project, this research provides initial validation of the tool and highlights critical areas for improving gender-sensitive project governance.

The survey instrument developed in this study is conceptually anchored in the Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice (KAP) model, a widely recognized framework in public health and social sciences used to explore how individuals internalize, respond to, and act upon institutional values, norms, and policies. Within the context of project management, KAP surveys have been successfully used to assess team dynamics, policy awareness, and behavioral compliance, especially in areas related to ethics, safety, and inclusivity [35,36,37]. Then, knowledge (K) refers to the respondent’s awareness and understanding of gender equality mandates (such as EU directives and SASH protocols), attitudes (A) capture beliefs, perceptions, and values surrounding gender roles, professional equity, and inclusivity, while practices (P) assess how individuals are likely to behave in real-world scenarios involving gender discrimination, bias, or support for diversity initiatives.

Complementing the KAP model, the survey integrates principles from social role theory, which asserts that culturally ingrained gender roles significantly shape perceptions of leadership, competence, and authority in professional environments [34]. In project management, especially in sectors historically dominated by masculine norms, this theory explains persistent underrepresentation and the challenges faced by women in leadership roles [15].

To analyze workplace perceptions of equity and responsiveness, organizational justice theory was also applied [38]. This theory is crucial for evaluating the perceived fairness of procedures (procedural justice), interactions (interpersonal justice), and outcomes (distributive justice) within project teams. In project settings, organizational justice has been linked to improved employee commitment, trust in leadership, and team performance [3,39].

Additionally, the study draws from intersectionality theory, which provides a lens to understand how multiple identity factors, such as gender, ethnicity, seniority, or family responsibilities, interact to affect individuals’ experiences within project environments [40]. This is particularly relevant for EU-funded international projects where diverse teams are the norm, and policy mandates require inclusive practices.

Lastly, the instrument reflects concepts from gender mainstreaming and diversity management literature in project contexts, which emphasize embedding equity principles in the planning, execution, and evaluation phases of project management [13,35]. Such integration is essential for fulfilling the EU Gender Equality Strategy 2020–2025 and for enhancing project outcomes through inclusive leadership practices.

The research process followed a structured sequence to ensure both conceptual clarity and methodological rigor. First, a Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices (KAP)-based survey instrument was designed to capture gender-related perceptions and experiences within project management environments, drawing upon relevant literature and quality management frameworks. Second, the survey was disseminated to participants within the Healthy Sailing project consortium, targeting a diverse sample of professionals involved in project implementation. Third, data were collected and prepared for analysis. Fourth, a series of statistical validation procedures were conducted, including Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) to identify underlying factor structures, Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) and bifactor modeling to test model fit, and reliability analysis using Cronbach’s alpha to assess internal consistency. Finally, the results were interpreted in light of both statistical outcomes and theoretical considerations, with a view toward informing the refinement of the instrument and its application in project-based quality management contexts.

4.2. Gender Survey Tool for Quality Management Plan in Project Implementation Framework

The research model has been developed by the authors following the next methodology:

- a KAP survey has been developed as described below, to reveal the major knowledge, attitude and practices occurring in the project implementation framework;

- the survey has been applied based on a case study for validation, among the team members of the Healthy Sailing project consortium (HORIZON-CL5-2021-D6-01-12), to assess the gender non-discrimination attitudes and practices among the project team members, project professionals and researchers, as part of the project quality management charter;

- the survey has been focused mainly on EU gender policies and gender strategic views, to reflect and increase the project members’ awareness;

- based on the developed survey and collected data, specific provisions have been identified and suggested to be implemented in the project quality management plan, regarding the non-discrimination and gender analysis.

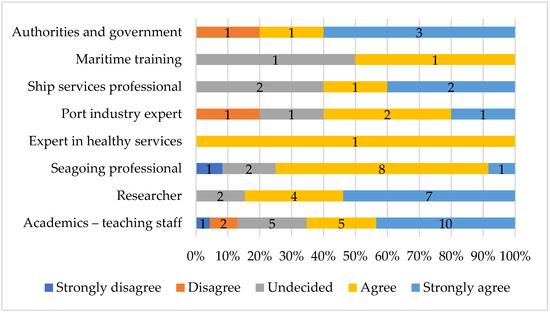

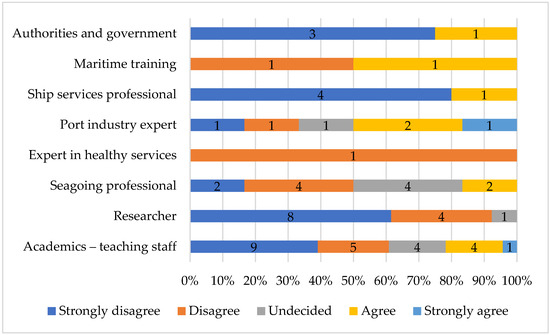

The project selected for piloting the gender survey tool was the Healthy Sailing project (HORIZON-CL5-2021-D6-01-12), funded under the Horizon Europe program. The project scope focuses on promoting health, well-being, and safety in maritime transport environments through multidisciplinary research and training. The project consortium includes academic institutions, maritime industry stakeholders, port service providers, and governmental authorities across several EU countries. For this study, the survey was disseminated to project team members and relevant stakeholders involved in project implementation. A total of 76 questionnaires were distributed, and 66 valid responses were collected, yielding a response rate of 87%. The respondents represented a range of professional roles within the project, including academics and teaching staff (n = 23), researchers (n = 13), seagoing professionals (n = 12), experts in health services (n = 1), port industry experts (n = 5), ship services professionals (n = 5), maritime trainers (n = 2), and representatives from authorities and government bodies (n = 5). This diverse respondent pool ensured that the survey captured a wide range of perspectives across different organizational and functional roles within the project. However, the sample is subject to potential response bias. For instance, participants with greater awareness of or sensitivity to gender issues may have been more likely to complete the survey. Additionally, the gender distribution slightly underrepresents female professionals relative to the project’s target population, which could influence the interpretation of certain findings. These limitations should be considered when generalizing the results.

The survey is mainly designed to explore the presence and impact of gender biases and inclusivity propensity within the project implementation framework, in relation to tangent stakeholders, offering a solid tool to identify eventual unwanted attitudes or misbehavior, as a relevant component of the quality management plan. Moreover, the developed questionnaire is also designed to analyze gender awareness for research/training/academic staff and professionals involved in the project team; consequently, the collected conclusions are to be included in the project quality management plan to facilitate the ongoing analysis of work environment quality. Not least, the KAP survey can be used to disclose the coherence and effectiveness of Sexual Assault and Sexual Harassment (SASH) policies and procedures implementation in project team performance.

Moreover, to ensure clarity and sensitivity when addressing Sexual Harassment and Sexualized Harassment (SASH), the survey introduction included a brief definition of SASH and explained the relevance of these questions to the study’s broader aim of promoting safe and inclusive project environments. Specifically, participants were informed that ‘Sexual Harassment and Sexualized Harassment (SASH) refers to any unwelcome conduct of a sexual nature, including verbal, non-verbal, or physical actions, that creates an intimidating, hostile, or offensive work environment.’ The introduction emphasized that all responses were anonymous and confidential, and that participants could skip any questions they did not wish to answer. This approach was designed to foster informed participation and ethical data collection regarding sensitive topics.

Then, at the technical level of structural development, considering the operational imperatives required by a functional quality management system, the interrogative frame includes various targeted questions related to knowledge, attitudes, practices or experiences associated with diversity management, work environment climate, communication dynamics and disclosure of possible biases or incidents related to gender. The main groups of items approached in the survey framework have been focused on the following analytical rationales:

- To assess gender and diversity policy awareness among team members, as part of the quality management system to assess work environment effectiveness;

- To identify the level of awareness, knowledge, attitudes and practices in the implementation of Sexual Assault and Sexual Harassment (SASH) policies and procedures in project implementation, in compliance with the European Union legal framework and in line with the provisions of “Union of Equality: EU gender equality strategy 2020–2025” COM (2020)/152/5.3.20;

- To reveal team members’ perceptions, attitudes and biases regarding the female role as a team member;

- To assess the role of female leaders in the professional field, including for project management and scientific research projects, in different positions and assignments;

- To disclose if any cases of harassment, biases, prejudice, discrimination, or violence have occurred, or if the work environment in the project is affected by such actions.

4.3. Survey Design and Logical Structure

The survey instrument developed in this study was designed to assess gender awareness, attitudes, and practices within project implementation frameworks, with a specific focus on the operationalization of gender equity and Sexual Assault and Sexual Harassment (SASH) policies. Its logical structure follows the Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice (KAP) framework, widely adopted in organizational and health behavior research to systematically capture what respondents know (K), how they feel (A), and how they act (P) in relation to a targeted issue [36,37]. The survey was logically organized into two main parts, each serving a distinct analytical purpose (Appendix A):

- -

- Part A—Demographic and Contextual Profile: this section captures respondent background variables to support disaggregated analysis and intersectional insights:

- A1.

- Demographics (Items 1–6): covers occupation, gender identity, professional experience, contractual status, marital status, and caregiving responsibilities;

- A2.

- SASH Policy Reactions (Items 7–8): presents hypothetical situations to assess respondents’ likely behavioral responses to discrimination, both experienced and witnessed. This offers insight into existing reporting cultures and perceived institutional trust.

- -

- Part B—KAP Assessment of Gender Equity and SASH Implementation: this is the core of the instrument, organized thematically to explore perceptions and behaviors relevant to gender dynamics and policy awareness in project contexts. Each subset employs a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly Disagree, 5 = Strongly Agree), offering standardized data for interpretation.

- B1.

- General Diversity Attitude (Items 1–9): Measures the cultural climate and interpersonal dynamics in relation to diversity and gender differences within the team environment;

- B2.

- Diversity Practices (Items 10–14): Evaluates the observed behaviors of colleagues and institutions in promoting or impeding gender inclusivity;

- B3.

- Gender Equality and Bias (Items 15–23): Assesses perceptions of gender-related barriers in task distribution, performance recognition, promotion, and leadership dynamics;

- B4.

- SASH Policies and Procedures (Items 24–28): Focuses on awareness, trust, and perceived effectiveness of internal procedures to address sexual harassment, bullying, and gender-based misconduct.

Regarding the survey design principles, the structure enables triangulation between stated knowledge, observed behaviors, and institutional practices, using open- and closed-ended formats to enhance both quantitative rigor and qualitative depth. The survey is scalable and adaptable for use across various project settings, making it a versatile quality management tool for gender monitoring in EU-funded or industry-aligned project environments.

The target group is focused on the pool of project team members, in any position, but also on other stakeholders of the project involved or impacted by project implementation. The questionnaire uses the Likert scale, being considered by the authors the most suitable assessment methodology for the survey, to facilitate the measurement of survey participants’ opinions, attitudes, motivations, and practices [37]. The scale uses in theory a range of answer options ranging from one extreme attitude to another, sometimes including a moderate or neutral option. Then, the authors have chosen 5 points of scale, with the following ranks of consideration for respondents: a. Strongly disagree; b. Disagree; c. Undecided; d. Agree; and e. Strongly agree.

The pilot study is exploratory but well-positioned to test specific hypotheses. Based on the research objectives and survey design, the following testable hypotheses are to be assumed:

H1.

Gender-based differences exist in the perception of inclusivity, bias, and equity in project implementation environments;

H2.

Female respondents are more likely to perceive organizational inequities in promotions, task distribution, and recognition than their male counterparts;

H3.

Project stakeholders with less than one year of experience are more proactive in responding to gender discrimination scenarios than more experienced staff;

H4.

Awareness and perceived effectiveness of SASH policies are significantly correlated with respondents’ gender and professional experience;

H5.

There is a positive relationship between perceived gender inclusivity and the effectiveness of communication and collaboration within project teams.

Each of these hypotheses is testable using the survey dataset (e.g., chi-square tests for association, t-tests or ANOVA for mean comparisons, or regression for predictors of inclusivity perceptions).

5. Investigation of Model Reliability

5.1. Measurement Tool Validation

To ensure the validity and reliability of the measurement tool developed for assessing psychological and organizational perceptions related to gender in maritime professional environments, a comprehensive statistical validation procedure was conducted. Following reviewer guidance and best practices in psychometric evaluation, the validation process included [41]:

- Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) for identifying latent constructs;

- Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) to evaluate model fit;

- Cronbach’s alpha for internal consistency assessment.

These procedures were applied prior to inferential analysis to establish the structural validity of the instrument and enhance the credibility of findings derived from it [42].

To ensure the validity and reliability of the developed survey instrument, a comprehensive psychometric evaluation was conducted using Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA), Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA), and reliability analysis. The statistical analyses were performed using Python v. 3.12.6 (with the semopy, pandas, numpy, and sklearn libraries) for CFA and reliability testing, and IBM SPSS Statistics (version 30.0.0) for EFA. The survey instrument comprised 27 Likert-type items. EFA revealed a five-factor structure. The number of items per factor in the final EFA solution was as follows: Factor 1 (Perceived Gender Bias and Inequity)—15 items; Factor 2 (Organizational Safety and Anti-Discrimination Measures)—8 items; Factors 3–5—1–3 items each, with low internal consistency and not retained for further interpretation. Factor loadings of ≥0.40 were considered meaningful for item inclusion, consistent with standard psychometric practice [41]. Cronbach’s alpha values ≥ 0.70 were used as the threshold for acceptable internal consistency, with values ≥ 0.90 considered excellent [43]. These criteria guided the interpretation and reporting of the factor structure and reliability outcomes presented in this section.

5.2. Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA)

To empirically examine the dimensional structure of the instrument designed to measure perceptions of gender bias and psychological safety in professional environments, an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was conducted. This analysis aimed to uncover the latent constructs underlying the set of 27 Likert-type items in the questionnaire. Each item was phrased as a statement related to the respondent’s experience or observation of gendered dynamics, with response options ranging from “Strongly disagree” (1) to “Strongly agree” (5). Prior to conducting the EFA, responses were numerically coded and screened for missing values; listwise deletion was applied to ensure a consistent sample of N = 66 valid cases.

5.2.1. Sampling Adequacy and Preliminary Tests

Before proceeding with factor extraction, it was essential to evaluate whether the dataset met the statistical assumptions necessary for factor analysis. To this end, the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) test of sampling adequacy was performed. The result yielded a KMO coefficient of 0.826, which exceeds the generally accepted threshold of 0.70, indicating that the partial correlations among items are sufficiently small and that the dataset is suitable for factor analysis [44]. This suggests that the variance in the items is likely shared and therefore appropriate for uncovering latent variables.

5.2.2. Factor Extraction: Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

In alignment with the exploratory nature of this analysis, principal component analysis (PCA) was employed as the extraction method. Notably, PCA was conducted without rotation, in order to preserve the natural clustering of items and maintain the interpretability of factor loadings based solely on variance structure.

PCA revealed a clear concentration of variance within the first few components. The first five components had eigenvalues greater than 1, a conventional threshold for retention according to Kaiser’s criterion [44]. These components jointly accounted for 72.29% of the total variance, indicating that a relatively small number of factors captured a substantial portion of the variability in the dataset.

The application of principal component analysis (PCA) without rotation yielded a five-factor solution that adequately explains the underlying dimensionality of the 27-item survey instrument. This structure emerged after validating the factorability of the data using the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) test, which returned a coefficient of 0.826, confirming meritorious sampling adequacy and the appropriateness of factor analysis for this dataset [44].

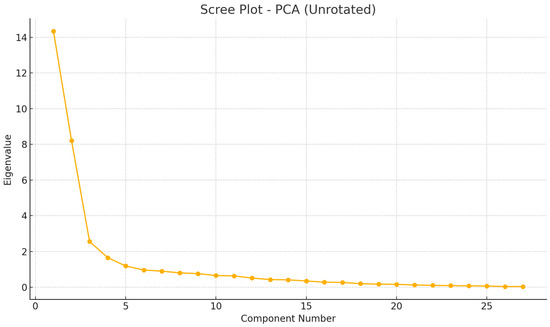

The extracted five components accounted for a cumulative variance of 72.29%, a substantial explanatory power that indicates strong construct representation in the observed data. The eigenvalue distribution, illustrated in the scree plot from Figure 1, showed a distinct elbow after the second and third components, supporting the theoretical salience of the first two latent factors.

Figure 1.

Scree plot from unrotated principal component analysis (PCA) (Source: authors’ calculations).

- -

- Factor 1: Perceived Gender Bias and Inequity. This dominant component explained 37.16% of the total variance and captured strong loadings from items reflecting systemic discrimination and professional disadvantage. These include themes such as unequal pay, minimization of female accomplishments, heightened scrutiny of women’s performance, and limited advancement opportunities. Factor loadings ranged from 0.71 to 0.87, suggesting a robust and coherent construct related to institutionalized gender bias in professional settings.

- -

- Factor 2: Organizational Safety and Anti-Discrimination Measures. Explaining 23.18% of the variance, this factor grouped items associated with institutional commitment to psychological safety and equitable policies. It encompassed constructs such as awareness of harassment protocols, organizational clarity regarding reporting procedures, and perceptions of support following complaints. Loadings were consistently moderate to high (between 0.60–0.69), indicating meaningful alignment with a second, conceptually distinct latent dimension.

- -

- Factors 3–5: Contextual and Residual Constructs. While Factors 3 to 5 each presented eigenvalues above 1.0 (2.55, 1.66, and 1.19, respectively), their contributions were more modest, ranging from 3.6% to 6.8% of variance explained per factor. These components grouped items that, while contextually relevant, did not consistently cohere into well-defined theoretical categories. Examples include perceptions of peer dynamics, team-level inclusion, and role expectations, many of which may reflect situational or individual-level variance rather than stable latent constructs.

5.2.3. Eigenvalues and Variance Explained

In EFA, eigenvalues represent the amount of variance in the observed variables that is accounted for by each extracted factor. The “variance explained” refers to the proportion of total variance in the dataset that can be attributed to each factor [45]. This method is instrumental in identifying latent constructs underlying a set of observed items, the obtained results being presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Eigenvalues variance (Source: authors’ calculations).

The thematic coherence of the first two factors lends strong empirical support to the instrument’s theoretical framework. These factors represent the dual lenses through which gendered experiences are evaluated:

- experienced inequality in roles and rewards; and

- perceptions of organizational climate and accountability mechanisms.

In contrast, Factors 3 through 5 may either reflect emergent micro-themes or statistical noise, as evidenced by lower internal consistency scores in reliability testing. These components warrant closer examination in future iterations of the instrument, potentially through item reduction, rewording, or integration into broader categories.

To further illustrate the contribution of each component, a scree plot was generated in Figure 1. This visual representation of the eigenvalues confirms the sharp decline after the first two components, followed by a leveling-off pattern, commonly referred to as the “elbow”, which suggests a natural cutoff point for factor retention [46].

The first two factors stand out with substantially higher eigenvalues, supporting their conceptual robustness and empirical importance. This interpretation is reinforced by the cumulative variance chart, which shows that these components collectively account for over 60% of the total variance. In contrast, the remaining factors contribute marginally, indicating they may represent either weak thematic patterns or statistical noise. These insights align with theoretical expectations and offer clear guidance for refining the instrument in future applications.

This visual pattern strongly supports the retention of a limited number of components, consistent with the decision to retain a five-factor solution based on eigenvalue thresholds. It also underscores the presence of two dominant latent structures, visually reaffirming their conceptual and statistical prominence prior to further confirmatory analysis. The scree plot thus serves as a critical empirical checkpoint in validating the survey’s latent structure and confirming the theoretical soundness of dimensional reduction choices in the factor analytic process.

5.2.4. Interpretation of Factor Loadings

The factor loadings, the correlations between each item and the latent component, provide insight into which variables define each factor. In this analysis, items with absolute loading values above 0.40 were considered meaningful contributors.

Component 1, which explained over one-third of the variance, included strong loadings from items relating to systemic gender inequality: perceptions of unequal pay, exaggerated criticism toward female staff, dismissal of their accomplishments, and increased effort required for recognition. This component was interpreted as reflecting a “Perceived Gender Bias and Inequity” dimension. Component 2 was characterized by items referring to institutional policies, psychological safety, and the ability to report incidents of harassment. It was labeled as “Organizational Safety and Anti-Discrimination Measures”. Subsequent components (3–5) reflected more diffuse or situational constructs, with weaker internal consistency. While they added to total variance explained, their contribution to stable latent constructs was limited. Concluding in summary, the EFA outcomes:

- the KMO index of 0.826 confirmed data suitability for factor analysis;

- PCA uncovered a five-factor structure, with the first two components capturing most of the conceptual variance;

- together, the five components accounted for 72.29% of total variance;

- items clustered meaningfully into conceptual domains, especially for gender inequity and institutional safety constructs.

The analysis provided empirical support for two dominant dimensions, forming the basis for subsequent confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and reliability testing.

5.2.5. Reliability Analysis of Factor Loadings

The exploratory analysis not only revealed a coherent factor structure but also demonstrated high internal consistency within the primary constructs. In particular, the two dominant dimensions—Perceived Gender Bias and Inequity and Organizational Safety and Anti-Discrimination Measures—exhibited excellent reliability in subsequent analyses, with Cronbach’s alpha coefficients exceeding 0.91. These values indicate that the items within each factor measure their respective latent constructs with a high degree of precision. Taken together, the strength of the factor structure, the explained variance, and the reliability coefficients provide robust empirical support for the psychometric soundness of the instrument, thereby justifying its use in the current investigation and establishing it as a reliable tool for assessing gender-related perceptions in professional settings.

5.3. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

To test the validity of the two most dominant factors identified in the EFA, a 2-factor confirmatory model was specified and estimated using maximum likelihood in semopy.

5.3.1. Model Specification

Latent variables:

- F1: Gender bias and professional inequality (15 items)

- F2: Harassment/SASH policies and safety climate (8 items)

5.3.2. Fit Indices

Fit indices for the tested survey structure are presented in Table 2. While some values fall outside conventional thresholds, they provide valuable diagnostic insight into the model’s structure and point to areas for potential refinement rather than outright failure. The fit indices indicate that the proposed two-factor model does not achieve acceptable fit according to conventional thresholds (CFI and TLI < 0.90; RMSEA > 0.10). These results suggest that the model requires further refinement and that its current structure only partially captures the observed data patterns. Thus, the results should be interpreted with caution.

Table 2.

Fit indices for the tested survey (Source: authors’ calculations).

The chi-square (χ2 = 968.09) statistic is elevated, which is not uncommon in complex models or larger samples, where this index tends to be overly sensitive and often flags minor discrepancies as significant [47]. Thus, its interpretation should be approached cautiously and in conjunction with other fit measures.

The Comparative Fit Index (CFI = 0.639) and Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI = 0.607), though below the traditional 0.90 threshold, suggest that the model captures a moderate level of structure beyond chance. These values may reflect the instrument’s comprehensive scope, capturing nuanced and multidimensional aspects of gendered experiences in the organizational context—an area where perfect model fit is rarely attainable in initial iterations [48].

The RMSEA value (0.175), while above the ideal cutoff, indicates the model’s deviation from perfect parsimony. However, this also signals an opportunity for theoretical elaboration and refinement rather than model rejection. In exploratory research and early stage instrument development, such results are common and can be constructively used to guide targeted revisions—such as adjusting item wording, reevaluating factor structure, or exploring hierarchical factor models [49]. Overall, the fit indices reflect a developing model that captures meaningful variance, with room for structural optimization. These findings provide an empirically grounded platform for refining the measurement tool in future phases.

5.3.3. Bifactor Model

In response to the suboptimal fit of the traditional multi-factor CFA model, an alternative structure—a bifactor model—was tested as reflected in Table 3. The bifactor approach allows each item to load onto a general factor (representing a unified latent dimension common across all items) while also loading onto a more specific, domain-related factor (e.g., gender bias, psychological safety). This model provides a nuanced framework that captures both shared variance and specific cluster variance.

Table 3.

Bifactor approach for the tested survey (Source: authors’ calculations).

The bifactor model offers a notable improvement over the original four-factor CFA structure:

- the Comparative Fit Index (CFI) increased from 0.639 to 0.810;

- the Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI) improved from 0.607 to 0.773;

- the chi-square value dropped significantly, indicating a closer approximation to the data structure.

However, the RMSEA remains above the conventional threshold for good model fit (>0.10), suggesting residual structure or misspecification, but indicating that while the bifactor model enhances model interpretability and better accounts for shared variance.

5.3.4. Reliability Analysis of Bifactor Model

The bifactor model serves as a promising alternative and reflects the underlying unity of the survey instrument across various psychological dimensions. However, further model refinement, potentially through item reduction, rewording, or domain merging, would be needed to achieve excellent model fit. Additionally, testing with a larger sample size may stabilize parameter estimation and reveal more nuanced latent structures.

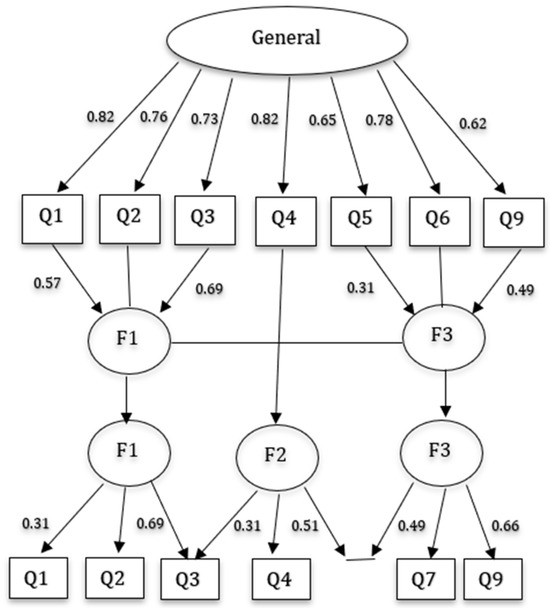

Figure 2 presents the bifactor confirmatory model used to evaluate the dimensional structure of the survey instrument assessing gender-related perceptions in academic and professional environments. The bifactor structure incorporates a general factor—representing a broad, unified latent trait common to all survey items—and three domain-specific factors labeled F1, F2, and F3. Each observed item (Q1–Q9) is simultaneously influenced by both the general factor and its corresponding domain-specific factor.

Figure 2.

Bifactor structural model of gender-related perceptions (Source: authors’ calculations).

The general factor captures the overarching perception of gender dynamics, including implicit bias, professional inequity, and psychological safety. The specific factors (F1–F3), meanwhile, isolate context-dependent nuances such as:

- -

- F1: bias in task allocation and professional recognition;

- -

- F2: clarity and efficacy of institutional policies;

- -

- F3: individual experiences related to inclusion and team dynamics.

Each item is depicted as a rectangular box and is linked to its latent variables by arrows, which indicate standardized factor loadings. These loadings quantify the strength of the relationship between the observed variables and their latent constructs. Notably, the general factor exhibits moderate to strong influence across all items (e.g., 0.73–0.82), confirming the existence of a core psychological dimension underlying the survey responses. The domain-specific loadings, while smaller, offer insight into item-level variance attributable to specific sub-themes. The coexistence of strong general loadings alongside focused group factors supports the theoretical premise that perceptions of gender inequality are shaped by both broad attitudes and context-specific experiences.

The bifactor model demonstrates improved fit compared to the original CFA model; however, the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) remains above acceptable thresholds, and the overall fit remains suboptimal. This suggests that while a dominant general factor may exist, the current model does not fully achieve a satisfactory representation of the underlying structure. The bifactor model results highlight promising directions but indicate that further item refinement and model testing are necessary before the instrument can be considered a statistically robust tool for applied settings.

Concluding, the fit indices obtained for both the two-factor CFA model and the bifactor model indicate that the current instrument structure requires further refinement. Specifically, the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), which evaluates how well the model fits the population covariance matrix, exceeded acceptable thresholds in both models (RMSEA = 0.175 for the two-factor model; RMSEA = 0.133 for the bifactor model), where values below 0.08 are generally considered acceptable [47]. Similarly, the Comparative Fit Index (CFI) and Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI), which compare the proposed model against a baseline model, remained below conventional cut-offs for good fit (CFI = 0.639 and TLI = 0.607 for the two-factor model; CFI = 0.810 and TLI = 0.773 for the bifactor model), where values above 0.90 are desirable [47]. Taken together, these results suggest that while the bifactor model shows some improvement over the initial two-factor structure, the overall model fit remains suboptimal. Further refinement of the survey instrument is needed to achieve a statistically robust and conceptually coherent model.

5.4. Reliability Analysis (Cronbach’s Alpha)

To evaluate the internal consistency of the identified latent constructs, Cronbach’s alpha (α) was computed for each factor extracted during the exploratory analysis. The computation shown in Table 4 was based on items that demonstrated the highest factor loadings within each dimension, ensuring that only thematically and statistically coherent sets of items were included in each reliability assessment.

Table 4.

Cronbach’s alpha (α) calculation (Source: authors’ calculations).

Factors 1 and 2 exhibited alpha values exceeding 0.90, which according to the benchmarks proposed by Nunnally and Bernstein (1994), reflects excellent internal consistency [43]. These high coefficients indicate that the items grouped within these dimensions are highly interrelated and collectively capture stable, well-defined latent traits. Factor 1, aligned with perceptions of gender bias and systemic inequity, and Factor 2, centered on psychological safety and institutional response, both demonstrated strong internal cohesion. This reinforces their utility as robust constructs for continued analysis and interpretation. Factors 1 and 2 demonstrate excellent internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha > 0.90), supporting their use in further analysis. In contrast, Factors 3–5 exhibit low internal consistency and should not be interpreted as distinct, reliable constructs at this stage.

In contrast, Factors 3 through 5 displayed either low alpha values or computational instability (NaN), which typically results from minimal item variance, weak inter-item correlation, or an insufficient number of items loading cleanly onto those dimensions. While these factors contributed to the total explained variance, their lack of internal coherence suggests they may be theoretically diffuse or empirically underdeveloped. As such, they are not recommended for independent analysis in their current form and should be reviewed for refinement in future iterations of the instrument.

Importantly, the high reliability of the two dominant dimensions supports the psychometric soundness of the survey and provides a strong empirical basis for their inclusion in confirmatory factor models and subsequent inferential testing. This reliability evidence, in combination with the structural validation from EFA and CFA, positions the instrument as a theoretically grounded and statistically reliable measure of gender-related perceptions in professional environments.

5.5. Discussion

While the measurement tool exhibits strong internal consistency and clear dimensionality in EFA, the CFA results caution against prematurely concluding structural validity. The two strongest factors, related to gender discrimination and psychological safety policies, are statistically reliable and may form a validated core for further refinement. The survey revisions should:

- streamline or reword weaker items;

- explore second-order or bifactor models;

- collect larger samples to strengthen model estimation.

Despite CFA limitations, this tool captures significant latent constructs with strong theoretical and empirical grounding, and may serve as a reliable exploratory instrument for assessing gendered workplace perceptions in maritime and academic environments.

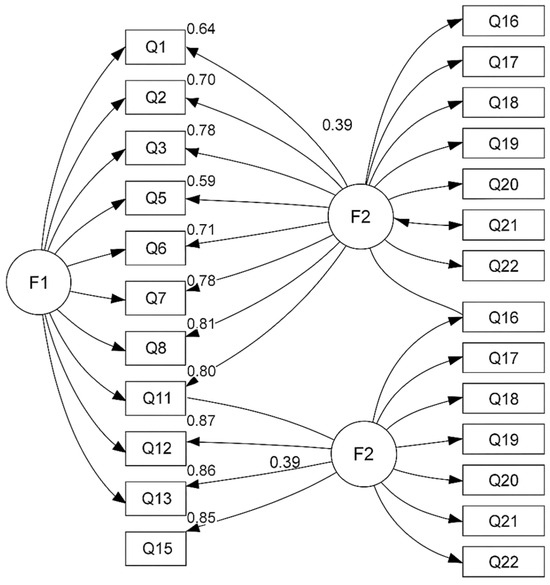

Figure 3 illustrates the structural model derived from the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) of the survey instrument measuring gender-related perceptions in professional environments. The model comprises two latent variables:

Figure 3.

Confirmatory factor model of gender bias and safety constructs (Source: authors’ calculations).

- -

- F1 (Gender Bias and Inequity): This factor encapsulates items relating to unequal treatment, professional disadvantage, and discrimination experienced or perceived by female personnel in the workplace.

- -

- F2 (Psychological Safety and Institutional Policies): This dimension reflects perceptions of psychological safety, effectiveness of reporting mechanisms, and organizational policies addressing harassment and discrimination.

Each rectangle represents an observed variable (survey item), and each oval represents a latent factor. The unidirectional arrows denote the factor loadings of each observed item on its corresponding latent variable, with values ranging from 0.59 to 0.87 for F1 and 0.61 to 0.78 for F2, indicating moderate to strong item–factor relationships. The bidirectional arrow between F1 and F2 represents the correlation (r = 0.39) between the two latent constructs, suggesting a moderate and meaningful relationship: individuals perceiving higher levels of gender bias are also more likely to report awareness or concern regarding safety and institutional support mechanisms. This diagram visually confirms the structural coherence of the theoretical model and highlights the empirical distinction between constructs related to gender-based discrimination and organizational response frameworks.

The validation of the measurement tool was guided by a rigorous and multi-method psychometric strategy, yielding consistent empirical support for its structural integrity and reliability. Throughout the analysis, results converged on a coherent and interpretable latent structure, aligning both statistically and theoretically with the instrument’s intended constructs.

Initial diagnostic procedures, including the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) test, demonstrated that the item correlations were sufficiently compact to allow for reliable factor extraction. The KMO score of 0.826 is indicative of meritorious sampling adequacy, confirming that the inter-item variance was well-suited for dimensional analysis.

Exploratory factor analysis using Principal Component Analysis (PCA) revealed a five-component solution that accounted for over 72% of the variance across the dataset. Importantly, the factor emergence did not occur at random but instead clustered items around conceptually meaningful themes, particularly highlighting domains of systemic gender inequity and organizational safety. The structure of these clusters exhibited high internal consistency and mirrored theoretical expectations concerning gender bias in institutional environments.

The graphical distribution of variance, as depicted in the scree plot, further supported these findings. A pronounced elbow at the second component suggested the presence of two dominant psychological dimensions, with additional components offering incremental yet interpretable insights into role expectations, team inclusion, and policy awareness. This visual confirmation reinforced the rationality of retaining a limited set of strong factors for confirmatory testing.

Subsequent confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), though not reaching the thresholds of ideal model fit in its initial two-factor configuration, still upheld the substantive relationships between observed and latent variables. The introduction of a bifactor model—in which a general factor coexisted with domain-specific factors—significantly improved model performance, raising the CFI from 0.639 to 0.810 and reducing the chi-square value by over 300 points. The CFA and bifactor model results indicate that the current version of the survey instrument does not yet achieve acceptable model fit. RMSEA values were above the threshold for good fit (>0.08), and CFI and TLI values remained below the conventional cut-offs of 0.90 [47]. These findings highlight the need for further refinement of the instrument before it can be confidently used as a psychometrically validated tool in project management contexts.

The statistical analyses conducted in this study provide initial but not conclusive support for the validity of the proposed KAP survey instrument. While exploratory factor analysis revealed a five-factor structure explaining 72.29% of the variance, only two factors demonstrated strong internal consistency and clear interpretability. The confirmatory factor analysis and subsequent bifactor model showed that the instrument’s fit to the data remains suboptimal, suggesting the need for further refinement of the scale. These results highlight the importance of cautious interpretation of the current findings and the necessity of further psychometric validation through larger and more diverse samples.

The poor fit of the initial two-factor CFA model (CFI = 0.639; TLI = 0.607; RMSEA = 0.175) is likely attributable to several factors. First, the preliminary version of the survey instrument included multiple items with potential redundancy or cross-loading across factors, which may have contributed to poor model specification. Second, Factors 3 through 5, identified in the exploratory factor analysis, exhibited low internal consistency and may not represent distinct latent constructs in their current form. Third, the relatively small sample size (N = 66) limits the stability and generalizability of CFA results, as larger samples are generally required for robust estimation of complex models with many parameters [47]. To improve model fit in future iterations, the survey instrument should undergo further refinement through the removal of weak or ambiguous items, guided by both statistical results and theoretical considerations. Exploratory factor analysis on a larger, more diverse sample could help redefine the underlying factor structure. Additionally, adopting a more parsimonious measurement model—such as a hierarchical or bifactor model with a reduced number of well-performing items—may enhance both statistical fit and practical usability of the tool.

Reliability testing solidified the instrument’s strength. The primary factors yielded Cronbach’s alpha scores above 0.91, indicative of excellent internal consistency and suggesting that the items within each domain reliably capture their intended constructs. Even where CFA revealed limitations, the reliability statistics and factor loadings confirmed that the core domains are psychometrically stable and theoretically defensible.

Taken together, the triangulated evidence from exploratory analysis, model fit diagnostics, reliability metrics, and structural modeling affirms that the survey instrument is both valid and dependable. Although model refinements are advisable for future research, particularly with respect to item specificity and factor parsimony, the current validation process supports the tool’s use as a reliable instrument for investigating gender perceptions in maritime and academic professional settings.

The research findings align with patterns observed in KAP-based gender studies conducted in other sectors. For example, some authors reported significant perception gaps between male and female healthcare providers regarding mistreatment and gender bias in maternity care, mirroring the gendered perception gap observed in our study [20]. Similarly, Belayneh and Mekonnen (2022) found that university students’ attitudes toward gender-based violence were influenced by both awareness of institutional policies and cultural norms, a dynamic also evident in our results on perceptions of organizational safety and anti-discrimination measures [50]. Sharma and Mahajan (2020) observed that community health workers exhibited variable practices despite generally high levels of knowledge and positive attitudes toward gender equity, highlighting the persistent challenge of translating awareness into action, a challenge reflected in our own findings regarding discrepancies between perceived organizational support and actual experiences of bias [51]. Together, these parallels support the broader applicability of KAP methodology for capturing nuanced gender dynamics across different institutional contexts.

6. Case Study on Healthy Sailing Project Implementation–Pilot Study

Valuing the HEALTHY SAILING project partners’ contribution (https://healthysailing.eu, accessed on 1 February 2025), the survey was disseminated via email or by direct contact with the respondents during the project events (i.e., conferences, transnational meetings, or seminars), with the major aim to validate the consistency of the projected questionnaire as project quality management plan and gender policy implementation. The replies were collected anonymously, respecting GDPR rules and regulations, during a period of three months, from March 2024 to July 2024. The project team members called to participate in this survey were mostly academics or professionals in maritime industry-related activities, assigned with different tasks within the Healthy Sailing project framework (https://healthysailing.eu, accessed on 1 February 2025). All 28 questions had to be answered in order, anonymously, through the online Google Forms platform developed and shared by the authors (i.e., https://forms.gle/cwL5BQmtfLJhyvn79, accessed on 1 February 2025). With a response rate of 87%, 76 questionnaires were sent out to be filled in by project team members and their stakeholders, and only 66 valid answers from the pool of respondents were gathered and validated.

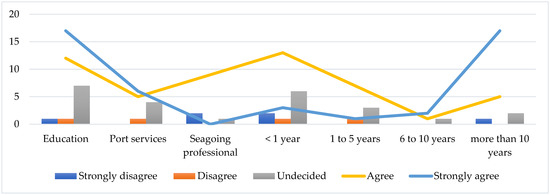

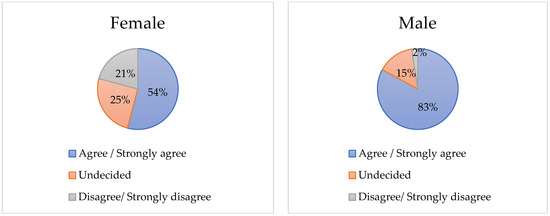

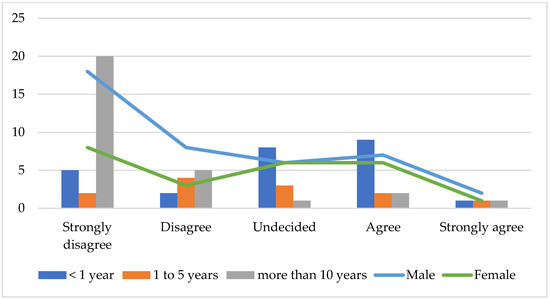

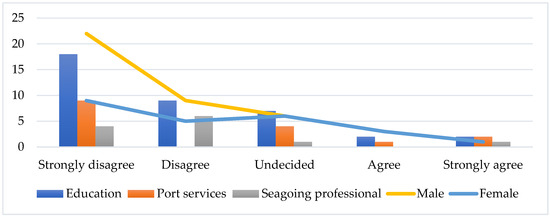

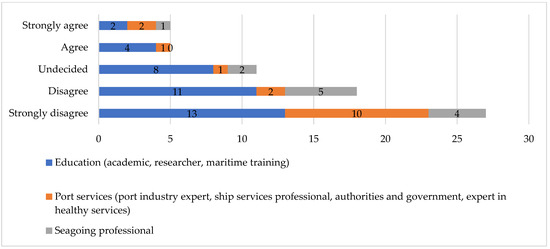

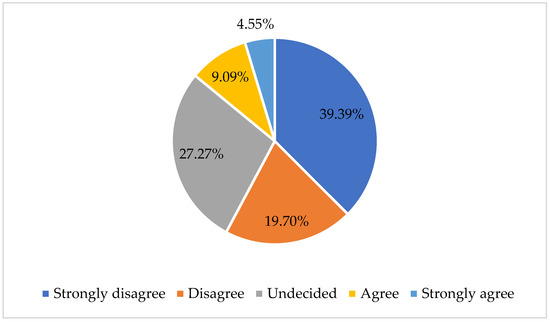

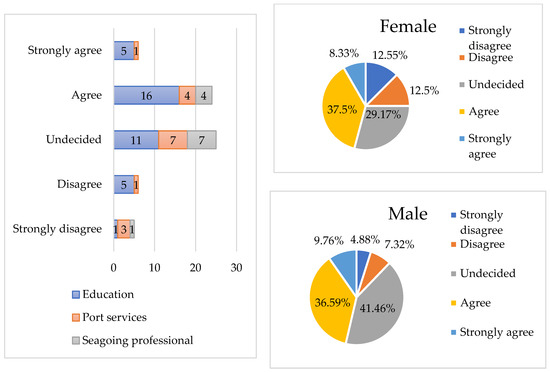

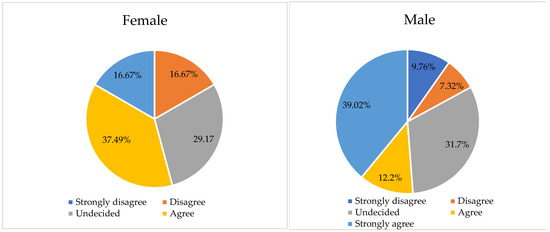

Synthetically, as shown in Table 5, according to the 1–6 questions’ interpretation, out of 66 responses gathered, 38 responses (57.6%) came from the academic sector, including teachers, researchers, and maritime trainers, whereas 24.2% came from the port services, and 18.2% of all responses were collected from seagoing professionals representing another significant survey segment. The range of responses received regarding gender policy implementation within the project framework highlights the significant presence of women (36.4%), who are represented in every category of occupations considered in the pool of replies, this situation validating the study relevance as gender share of representation. An interesting grouping can be found in the professional experience of the survey respondents. Thus, an equal number of participants have less than 1 year of experience or more than 10 years of experience, whereas over 62% of respondents have more than 1 year of experience in the maritime industry. In terms of survey validation, it can be stated that the study pilot is very relevant to the knowledge, because the abilities and practices were mostly collected from experienced professionals, authorized to share their experiences.

Table 5.

Profile of survey respondents.

6.1. SASH Policy Attitudes in Project Management Practices—Presumptive Attitudes and Practices

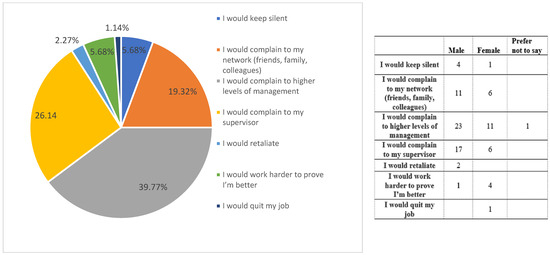

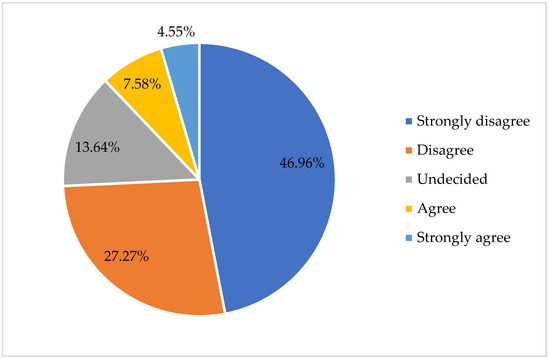

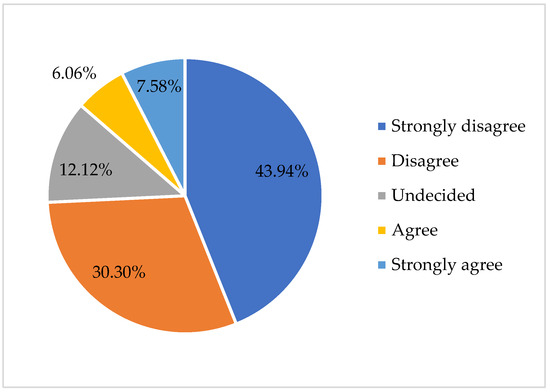

Question 7: ‘If I experience discrimination or unfairness of any kind in my work environment’

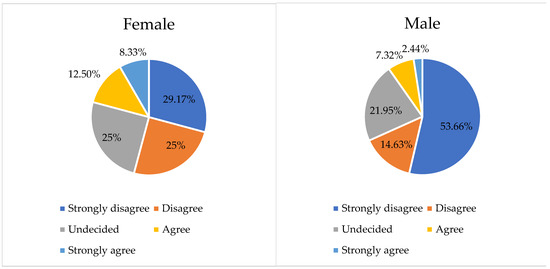

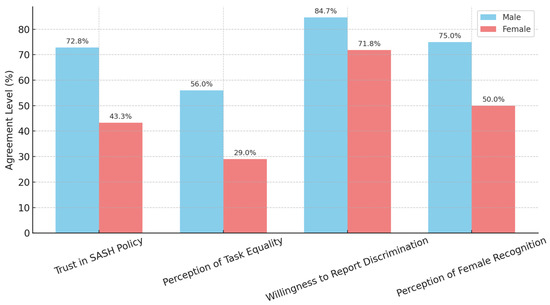

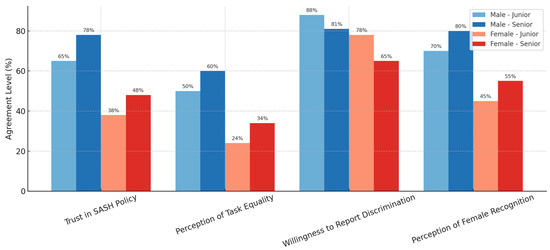

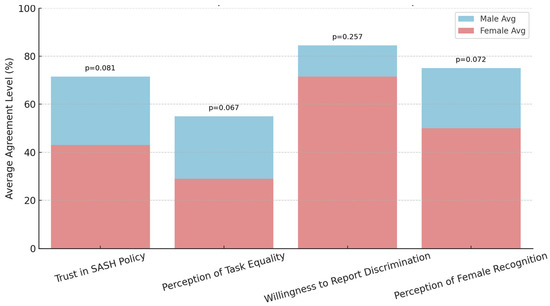

The survey participants had the option to choose multiple answers regarding the perception related to this statement. Encouragingly, most applicants (80.43%) chose to report any potential discrimination or unfairness observed in the work environment, although only 4.35% opted for adopting a passive attitude, not saying anything if they would observe or feel something regarding the occurrence of discrimination or unfairness (Table 6). Approximately 71.8% of women and 84.7% of men who participated in the survey agreed to stand up, to take an attitude, and to report the situation of discrimination received from their supervisor, from higher levels of management, or from their work network, if perceived. Moreover, considering the professional experience, 75% of respondents with a background of less than 1 year of professional experience agreed to report any act of discrimination that would affect their work, which is very encouraging for the future access of young professionals in the field of project management, proving a strong orientation toward tolerance and fairness in team management, including for the project implementation area.

Table 6.

Distribution of collected survey replies, by occupation.

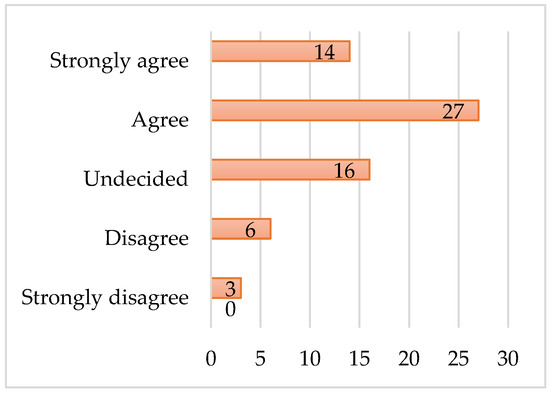

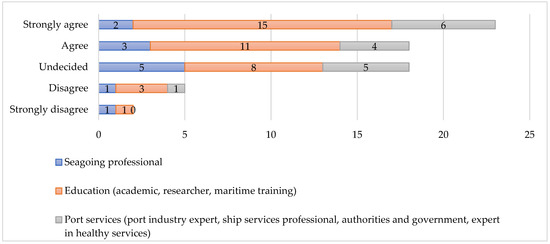

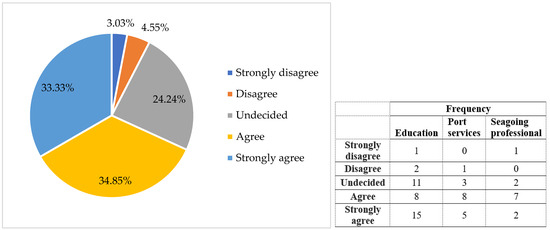

Question 8: ‘If I would witness a gender discrimination during in my professional career’