Abstract

This initial exploratory study examined the perceptions of teachers and school leaders in the Republic of Ireland regarding diversity in promotions to school principalship, framed by Equity Theory, Organisational Justice Theory, and Legitimacy Theory. A mixed-methods approach was utilised within this study. Data was collected from 123 participants via an online survey comprising Likert-type statements and open-ended questions. This data was analysed using descriptive statistics and quantitative analysis for the Likert-type statements and thematic analysis was used to examine the qualitative responses, allowing for the identification of recurring patterns and themes to complement the quantitative findings. Findings indicated disparities between perceived and desired prioritisation of diversity, alongside varied perceptions of its impact on school performance and leadership. Disability, social class, and religious diversity were perceived as the least prioritised in promotion practices, while gender and cultural diversity received greater support and were more frequently linked to positive leadership outcomes. Participants reported mixed perceptions across diversity dimensions, with gender, age, and cultural diversity associated with the most positive impacts. Concerns about tokenism and the perceived undermining of merit-based promotion were widespread, reflecting the importance of fairness, transparency, and alignment with stakeholder expectations. The study underscored the need for promotion processes that are both equitable and credible, and for organisational cultures that enable diverse leaders to thrive. These findings provided a foundation for further research and policy development to foster inclusive and representative school leadership in Ireland.

1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Context

School leadership is widely recognised as one of the most challenging and multifaceted roles within the education system, requiring individuals to navigate ongoing change, complexity, and accountability [1]. Governments and educational bodies invest significant resources into recruiting and supporting school leaders, acknowledging that effective leadership plays a pivotal role in promoting school quality and improving student outcomes [2,3]. Indeed, leadership is regarded as the second most important school-based factor influencing pupil learning, following classroom teaching [4]. Principals serve as the central agents of school improvement, and even under-resourced schools can thrive under strong leadership [5]. The breadth of the principal’s responsibilities is considerable, encompassing personnel and organisational management, instructional leadership, administrative and financial oversight, community engagement, and coordination with external agencies [6].

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) is an intergovernmental organisation through which member states collaborate to develop evidence-based policies and comparative data [7]. Across OECD countries, increasing policy emphasis on standardisation, performativity, and accountability has heightened pressures on school leaders [8]. Consequently, many principals are experiencing significant levels of stress and burnout, with global reports indicating early retirements and a reluctance among prospective candidates to apply for vacant roles [9,10].This leadership crisis is also evident in the Irish context, where principals report rising levels of mental health difficulties and a lack of work–life balance [11,12]. Against this backdrop of increased strain and diminishing interest in school leadership, concerns around the diversity of the profession have also emerged. The Republic of Ireland remains a largely homogenous society, predominantly white, Irish, and Catholic and this demographic profile is mirrored in the teaching workforce, particularly at primary level, where the majority are white Irish females [13,14]. However, Ireland’s school-aged population (5–18 years) is characterised by both a strong White Irish majority and growing ethnic and linguistic diversity. Approximately three-quarters of students at primary school level identify as White Irish, while the remainder belong to minority ethnic groups, including Other White, Mixed, Asian, Black, and Irish Traveller communities [15]. Around one in five students has an immigrant background, with 6% born abroad and a further 15% born in Ireland to non-Irish born parents [15]. Linguistic diversity is also evident, with almost one-third of pupils speaking a language other than English or Irish at home [15]. Gender distribution across primary and post-primary levels is relatively even, reflecting broader population trends [16].

Diversity in the workforce is essential for fostering inclusive environments, enhancing organisational effectiveness, and reflecting the pluralistic societies that institutions serve [17]. In the context of education, a diverse teaching workforce offers varied perspectives, promotes equity, and better supports the cultural and social needs of all students [18]. However, in The Republic of Ireland, the education sector remains notably homogenous [19]. This lack of diversity has implications for the leadership pipeline, as underrepresentation at the classroom level restricts opportunities for minority groups to progress into leadership roles [20]. Consequently, schools may miss the opportunity to benefit from the broader range of experiences, insights, and leadership styles that diversity can bring with Grissom et al. [21] noting that pupils benefit when their demographics are reflected within the school leadership team. Addressing this gap is critical not only for fairness and representation but also for strengthening the education system’s responsiveness to an increasingly diverse pupil population [22]. This is not a situation that is unique in The Republic of Ireland, as it can also be seen across several contexts including the United Kingdom, Australia, Germany and The Netherlands [23,24,25,26]. Irish research has long advocated for the importance of increasing diversity within the teaching profession, particularly in terms of ethnicity, socio-economic background, gender, religion and (dis)ability [27,28,29,30,31,32,33].

The Irish educational system is divided into primary and post-primary levels, each facing distinct challenges. Nearly 60% of primary school principals in Ireland are teaching principals, balancing classroom responsibilities with administrative tasks, while the remaining 40% are full-time administrative principals, often in larger urban schools [34,35]. Primary school principals report high levels of work-related stress, with many citing the unsustainability of their roles and poor work–life balance [11], thus making it an unattractive position to occupy. The administrative burden is further intensified by numerous circulars issued by the Department of Education, which focused largely on administrative rather than pedagogical tasks [2]. This has led to calls for more support and intervention at national and EU levels [12]. In post-primary education, school leaders, including principals and deputy principals, similarly face stress from excessive administrative duties, leading to burnout [36]. Concerns have also been raised about the effectiveness of school boards of management, which often rely heavily on principals for leadership, adding to their workload [35]. These challenges contribute to a recruitment crisis, with high stress levels deterring potential candidates [2].

1.2. Theoretical Framework

This initial exploratory study is grounded in three theoretical lenses (Equity Theory, Organisational Justice Theory and Legitimacy Theory), Equity Theory [37], posits that fairness exists when outcomes such as promotions are proportional to inputs like ability, training, and effort. Perceived imbalances create discomfort, prompting individuals to restore balance directly or indirectly [38]. The theory has been widely applied in organisational and educational research to examine fairness in promotions [39,40] and is particularly relevant in educational leadership, where processes can be unclear or influenced by informal networks [41]. Teachers and leaders from underrepresented groups may feel overlooked despite equal or greater inputs, while some majority-group members perceive diversity initiatives as conferring unfair advantages [42]. Kaiser et al. [42] support this dynamic in their series of seven experiments, showing that organisational diversity initiatives can heighten perceptions of racial victimhood among majority-group members, who may interpret such measures as signalling that their own contributions are undervalued. Organisational Justice Theory [43] extends this perspective by focusing on the fairness and transparency of processes (procedural justice) and the quality of interpersonal treatment (interactional justice), both of which are important for understanding concerns about tokenism. Legitimacy Theory [44,45] adds that diversity initiatives must align with stakeholder values and expectations to maintain trust. Together, these theories provide a robust framework for exploring educators’ perceptions, offering insights into both micro-level experiences of fairness and macro-level processes of institutional legitimacy. Table 1 summarises the core focus, principles, and practical aims of each theory as applied in this study.

Table 1.

Theoretical Framework.

The survey was designed with these three theories in mind, using Likert-scale items to assess perceptions of whether specific diversity dimensions were or should have been prioritised in promotions, their perceived impact on leadership outcomes, and views on tokenism. In the Irish context, where the leadership workforce remains largely homogenous despite increasing pupil diversity [15,19], these theories guided both the survey design and the interpretation of findings.

1.3. Rationale for the Study

The lack of diversity in school leadership roles, particularly in The Republic of Ireland, presents a significant challenge. The Republic of Ireland’s educational system is homogenous [19], with limited representation of various diversity groups, including (a) age (b) disability (c) gender (d) national origin and cultural (e) racial and ethnic (f) sexual orientation (g) social class and (h) religious, within leadership positions [46]. This underrepresentation can be traced back to a lack of diversity in the teacher pipeline, which ultimately affects the promotion of diverse candidates to leadership roles. This study is timely as it is the first to explore the perceptions of teachers and school leaders across both primary and post-primary sectors in The Republic of Ireland regarding perceptions of diversity in the promotion to school principal. This study seeks to adopt an exploratory approach to garner the perceptions of the participants and to identify any initial themes that will inform subsequent, more in-depth analyses.

1.4. Objectives

The aim of this study is to examine the perceptions of teachers and leaders in primary and post-primary schools in Republic of Ireland regarding diversity in the promotion to the role of school principal. The objective is to:

- To examine the perceived prioritisation of various diversity dimensions in school leadership promotions and the impact on leadership effectiveness and school performance.

1.5. Research Questions

This study will address the following research questions:

- To what extent do teachers and school leaders perceive that various forms of diversity are prioritised in promotion decisions within schools?

- Do teachers and school leaders believe that these forms of diversity should be prioritised in the promotion to leadership roles?

- What impact do teachers and school leaders perceive prioritising these forms of diversity to have on school performance and leadership effectiveness?

These questions aim to explore the current perceptions regarding diversity in Irish leadership promotions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

This study employed a mixed-methods research design using a survey-based approach to explore the perceptions of teachers and school leaders in primary and post-primary schools in The Republic of Ireland regarding diversity in the promotion to the role of school principal complemented by a short qualitative data collection. A cross-sectional survey design was utilised, as it allowed for the collection of data at one point in time, providing a snapshot of participants’ views on diversity in leadership recruitment [47]. The research employed Likert scale questions to gauge perceptions on the prioritisation of different diversity dimensions in promotion decisions and their perceived impact on school leadership and performance. Open ended questions were employed at the end of the survey to allow participants to add depth to their previous answers. This approach was appropriate for examining trends and patterns in perceptions across a large sample, enabling generalisation of findings to the wider population of teachers and school leaders in The Republic of Ireland [48].

2.2. Instrumentation and Survey Design

The primary instrument for data collection was an online survey designed to capture the perceptions of teachers and school leaders regarding diversity in promotion to leadership roles. The survey consisted of both closed-ended questions (using Likert scales) and open-ended questions, with the primary focus of this paper on the Likert scale responses for the quantitative analysis, while the open-ended responses provide complementary qualitative insights through thematic analysis. The Likert scale questions asked participants to rate their agreement or disagreement with statements related to the prioritisation of diversity in promotion decisions and the perceived impact of diversity on leadership effectiveness and school performance. These questions covered eight dimensions of diversity: age, disability, gender, national origin and culture, race and ethnicity, sexual orientation, social class, and religious affiliation.

2.3. Data Collection Procedures

Data was collected through Qualtrics, an online survey platform used to design and distribute questionnaires, which in this case was distributed via email to a randomly selected sample of teachers and school leaders through a publicly available database and on selected social media sites. An invitation to participate was sent to participants, outlining the study’s purpose, the voluntary nature of participation, and the estimated time commitment, participants were also encouraged to share this survey with their colleagues. The survey remained open for a period of four weeks, allowing participants ample time to respond. Participation was anonymous, and no identifying information was collected. The survey was designed to be accessible on multiple devices, including smartphones and computers, to encourage broad participation. When the data collection period had concluded, responses were exported into SPSS software (version 29.0.2.0) for statistical analysis. Given the online nature of the survey, it ensured a streamlined and efficient data collection process while providing participants the flexibility to complete the survey at their convenience.

2.4. Participants

A total of 123 participants fully completed the online survey. This included primary and post-primary school teachers currently working in The Republic of Ireland, namely principals, deputy principals, assistant principals (I and II), class teachers, and guidance counsellors. As the survey included both Likert-type statements and open-ended questions and not everyone completed both fully, it was decided by the authors that only responses with fully completed Likert-type statements would be included in the analysis. This sample size will allow for meaningful statistical analysis and help ensure that the findings are both reliable and valid [49].

2.5. Ethical Considerations

This study adhered to the ethical guidelines set forth by the host institution’s Education and Health Sciences Ethics Committee (approval code: 2024_12_26_EHS). Informed consent was obtained from all participants, ensuring they were fully aware of the study’s purpose, their right to withdraw up to the point of survey completion without penalty, and the confidentiality of their responses. No personally identifiable information was collected, and all data was collected anonymously. Participants were assured that their participation was voluntary and that their responses will only be used for research purposes. Ethical considerations regarding data security and privacy were rigorously maintained throughout the study.

2.6. Data Analysis Techniques

The data analysis for this study comprised demographic questions, Likert scale questions, and open-ended questions. The demographic and Likert scale questions were analysed using descriptive statistics, which provided a clear overview of the participants’ characteristics and their responses to the structured questions. Descriptive statistics are essential in summarising and organising data in a meaningful way, allowing researchers to identify patterns and trends [50].

The open-ended questions were analysed using thematic analysis. which involved identifying and interpreting themes within the qualitative data. Thematic analysis was conducted following Braun and Clarke’s [51] six-phase framework, with the data coded and organised using NVivo software (version 14.23.0). An inductive approach was taken, allowing themes to emerge from the data rather than being guided by pre-existing theoretical constructs [51]. Direct quotes from participants, anonymised by role (e.g., “Teacher”, “Principal”), were included in the results to illustrate and support the identified themes. This method supported the findings from the descriptive statistics by providing deeper insights into the participants’ experiences and perspectives. Thematic analysis is a valuable tool for qualitative research as it enables the exploration of complex data and the identification of recurring themes [51].

Participants were analysed together due to the relatively small sample sizes within each subgroup and to highlight shared perspectives across roles in relation to the research questions. While the sample included 64 teachers, 14 Assistant Principals I, 15 Assistant Principals II, 1 Guidance Counsellor, 11 Deputy Principals, and 32 Principals, the overlapping nature of roles in the Irish educational context (e.g., teachers simultaneously holding assistant principal posts, teaching principals at primary school level, etc.) meant that subgroup comparisons would not have been statistically robust. Therefore, responses were considered collectively.

3. Results

The results show varied perceptions of diversity and inclusion in school promotions. Participant demographics are provided first (Table 2), followed by survey statistics (Table 3, Table 4, Table 5 and Table 6) and net agreement figures (Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4) addressing the research questions: (i) are these diversities prioritised; (ii) should they be; (iii) does prioritisation improve school performance and leadership effectiveness and (iv) perceptions of diversity and merit in promotion practices.

Table 2.

Demographics.

Table 3.

Is this diversity prioritized in promotions?

Table 4.

Should this diversity be prioritised in promotions?

Table 5.

Prioritising this diversity positively impacts school performance and leadership effectiveness.

Table 6.

Perceptions of Diversity and Merit in Promotion Practices.

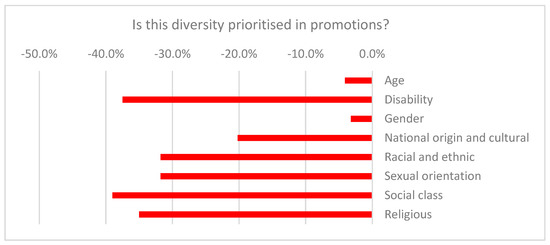

Figure 1.

Net agreement of “Is this diversity prioritised in promotions?”.

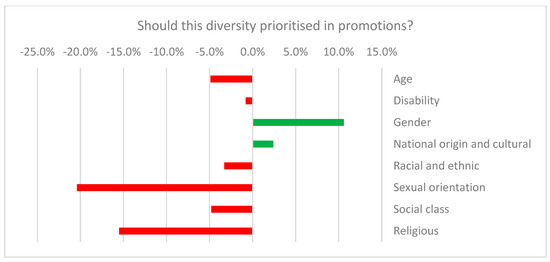

Figure 2.

Net agreement of “Should this diversity be prioritised in promotions?”.

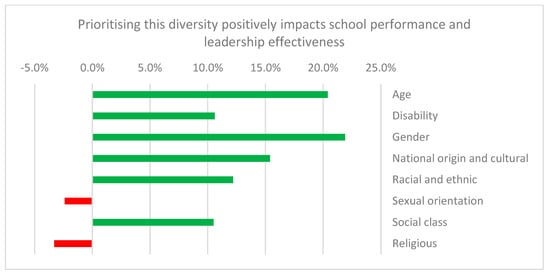

Figure 3.

Net agreement of “Prioritising this diversity positively impacts school performance and leadership effectiveness”.

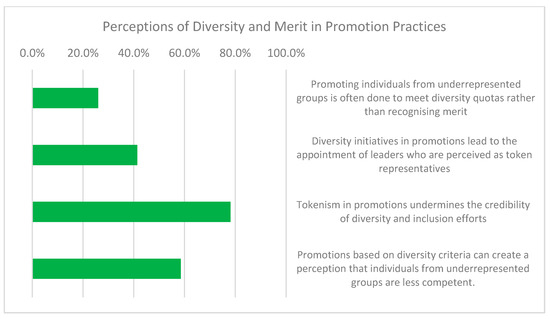

Figure 4.

Net agreement of Perceptions of Diversity and Merit in Promotion Practices.

This section presents quantitative trends and some qualitative insights on perceptions of diversity in school promotions, highlighting the complexity of attitudes towards diversity, merit and leadership effectiveness. It is organised into five sections: (i) Perceived Prioritisation of Diversity; (ii) Desired Prioritisation of Diversity; (iii) Perceived Impact of Diversity on School Performance and Leadership; (iv) Perceptions of Tokenism and Merit in Promotions; and (v) Summary. To summarise the overall balance of opinion for each statement, we calculated net agreement by subtracting the percentage of participants who disagreed from the percentage who agreed. This provides a single value that indicates whether the overall sentiment leans positive or negative: positive scores reflect a greater proportion of agreement (coloured in green), negative scores indicate more disagreement (coloured in red), and a score of zero suggests a balanced or neutral response. This approach provides a single directional measure that captures both the magnitude and polarity of opinion and has been employed in previous research across diverse fields [52,53].

3.1. Perceived Prioritisation of Diversity

Table 3 presents the data for the perceived prioritisation of different diversity dimensions in school promotion processes whilst Figure 1 details the net agreement scores. 9.7% of participants agreed that disability diversity is prioritised, compared with 47.2% who disagreed, producing a net agreement of −37.5%. One participant noted, “the teaching cohort is still primarily white Irish and non-disabled so there isn’t a range of available candidates that represents societal diversity” (Principal). Social class diversity received similar scores, with 11.4% agreement and 50.4% disagreement, giving a net agreement of −39%. Religious diversity (−35%), racial and ethnic diversity (−31.8%), and sexual orientation diversity (−31.8%) all recorded negative net agreement values. One participant stated, “the primary school profession are largely present as a homogenous group of white, female, heterosexual, Catholics” (Teacher). Age diversity had 32.5% agreement and 36.6% disagreement (−4.1% net agreement). Gender diversity had 35% agreement and 38.2% disagreement (−3.2% net agreement). National origin and cultural diversity recorded a net agreement of −20.2%. One participant observed, “Schools often struggle with bias—both conscious and unconscious—when selecting staff for promotions” (Principal).

3.2. Desired Prioritisation of Diversity

Table 4 and Figure 2 show a shift towards higher net agreement scores when participants were asked if diversity dimensions should be prioritised. Gender diversity recorded the highest support, with 46.4% agreement and 35.8% disagreement, resulting in a net agreement of +10.6%. One participant stated, “while diverse leadership is a positive as a whole, the promotion shouldn’t be given just based on gender, race, etc” (Assistant Principal 2). National origin and cultural diversity followed, with 40.7% agreement and 38.3% disagreement (+2.4% net agreement). Other dimensions showed lower support. Disability diversity had 39% agreement and 39.8% disagreement (−0.8% net agreement). Racial and ethnic diversity recorded −3.3% net agreement. Sexual orientation diversity received 26.8% agreement and 47.2% disagreement (−20.4% net agreement). Religious diversity had 29.2% agreement and 44.7% disagreement (−15.5% net agreement). One participant commented, “Catholic ethos of the majority of schools is an issue and problematic in meeting the need for religious and sexual orientation diversity to be realised” (Principal). All diversity dimensions with the exception of age (being similar), were more favourably looked upon in terms of desire for inclusion in promotional practices.

3.3. Perceived Impact of Diversity on School Performance and Leadership

Table 5 details how the participants perceive each diversity dimension to impact on school performance and leadership effectiveness whilst Figure 3 displays the net agreement figures. The table shows that gender and age diversity had the highest positive net agreement scores for perceived impact on school performance and leadership. Gender diversity received 48.8% agreement and 26.9% disagreement, giving a net agreement of +21.9%. Age diversity had the same agreement level (48.8%) and 28.4% disagreement, resulting in a +20.4% net agreement. One participant noted, “young qualified teachers, perhaps with a master’s qualification, can be perceived as more competent, yet may lack the experience and common sense of older teachers” (Principal). National origin and cultural diversity recorded +15.4% net agreement, racial and ethnic diversity +12.2%, and disability diversity +10.6%. Sexual orientation diversity had −2.4% net agreement, and religious diversity −3.3%. One participant stated, “nothing outside of hard work and competency should result in promotion, specifically not meeting certain diversity criteria” (Teacher). Despite clear perceptions of many diversity dimensions not being considered and not desired for consideration by the participants, it was quite clear that they mostly recognised the value of the dimensions to school performance and leadership effectiveness.

3.4. Perceptions of Tokenism and Merit in Promotions

Table 6 displays the perceptions of meritocracy in promotional decisions, further emphasised by Figure 4 which displays the net agreement scores. This shows that 83.8% of participants agreed that tokenism undermines the credibility of diversity and inclusion efforts, compared with 5.7% who disagreed, producing a net agreement of +78.1%. One participant remarked, “tokenism can create the illusion of diversity without meaningful inclusion, leading to resentment and undermining credibility” (Teacher). A total of 67.5% agreed that promotions based on diversity criteria can create perceptions of reduced competence among individuals from underrepresented groups (+58.5% net agreement). 60.1% agreed that diversity initiatives lead to the appointment of leaders perceived as token representatives (+41.4% net agreement). In addition, 51.2% agreed that individuals from underrepresented groups are often promoted to meet diversity quotas rather than based on merit (+26% net agreement). One participant stated, “the unsuccessful candidate(s) may take umbrage when/if a candidate from diverse and underrepresented groups is appointed to a promotional position as it could be seen as tokenism” (Deputy Principal). Despite the participant recognising the value of most diversity dimensions and their perceived impact on school performance and leadership effectiveness, there was clear scepticism when it came to implementing these as can be seen from the data presented above.

3.5. Summary

The results reveal complex and often ambivalent perceptions of diversity in school promotion processes. Across multiple diversity dimensions, participants generally reported that little prioritisation currently occurs, with disability, social class, religion, race and ethnicity, and sexual orientation all recording strongly negative net agreement scores. Qualitative comments suggested this reflects the limited diversity within the teaching workforce itself and the dominance of a largely homogenous profession. When asked whether diversity should be prioritised, responses were more supportive, particularly regarding gender and cultural or national origin, though scepticism remained about initiatives that might override merit. Perceptions of diversity’s impact on school performance and leadership were more positive, with gender and age diversity receiving the strongest endorsement, followed by cultural and national origin, race and ethnicity, and disability. However, negative views persisted regarding religion and sexual orientation. Concerns about tokenism were striking, with more than four in five agreeing it undermines the credibility of diversity initiatives, and substantial proportions believing such measures could reduce perceived competence or lead to symbolic appointments. These findings suggest that while some support for greater diversity exists, it is tempered by strong anxieties around fairness, merit and legitimacy.

4. Discussion

This initial exploratory study contributes to an emerging body of research examining diversity within educational leadership, specifically focusing on the perceptions of teachers and school leaders in The Republic of Ireland. Findings reveal complex and, at times, contradictory views about the prioritisation and perceived value of diversity initiatives, underpinned by concerns surrounding merit, tokenism, and the authenticity of inclusion efforts. This discussion contextualises these findings within existing literature and explores the implications for policy and practice.

4.1. Perceived Prioritisation of Diversity Dimensions

Participants consistently perceived that diversity was inadequately prioritised in promotional processes across several of the domains presented to them, namely disability, social class, religious affiliation, and racial and ethnic backgrounds. This is consistent with wider research highlighting the persistent underrepresentation of minority groups within school leadership pipelines [54], not only in The Republic of Ireland but also across comparable international contexts such as the United Kingdom, Australia, and Germany [55,56,57]. Despite a growing awareness of the need for diverse representation, structural barriers appear deeply entrenched, limiting access for candidates from underrepresented groups [18]. The considerable negative net agreements reported, particularly for disability and social class diversity, underline the extent to which promotional pathways are perceived to privilege traditional demographics.

4.2. Selective Support for Certain Diversity Categories

Participants expressed greater support for the prioritisation of gender and cultural diversity than for other diversity dimensions. This selective acceptance mirrors patterns identified in international studies, where gender equity initiatives have received comparatively more focus than other forms of diversity [58], perhaps due to their longer historical presence within educational reforms. However, while gender diversity was more readily supported, researchers caution against assuming that gender parity equates to genuine inclusivity. Ryan [59] argues that focusing solely on numerical representation can obscure persistent systemic inequalities. The marginalisation of other identity categories such as disability, religious affiliation, and sexual orientation suggests that diversity initiatives risk becoming overly narrow in scope unless consciously broadened [60,61,62].

4.3. Perceptions of Diversity Impact on Leadership Outcomes

The perceived impact of diversity on school leadership and organisational performance presents a similarly nuanced picture. Participants were most likely to associate positive outcomes with the prioritisation of gender, age, and cultural diversity, whereas sexual orientation and religious diversity were more likely to be met with scepticism. This aligns with existing literature, including the findings and discussions of Maji et al. [63] and Héliot et al. [60], who highlight that sexual orientation and religious diversity are often marginalised or inadequately addressed in workplace diversity initiatives. Research on gender identity, sexuality, and sexual orientation within organisations has been significantly overlooked until recently [64]. The prolonged absence of discussions within the literature on sexuality in management and leadership [65,66] can be attributed to two scenarios: the perception of sexuality as a taboo subject and the binary assumptions prevalent in gender discourse within organisations [64]. Compton and Dougherty [67] also noted that the silencing of non-normative identities is part of organisational experience.

The scepticism around religious diversity could be linked to the separation of state and religion within The Republic of Ireland, where Catholicism once dominated the educational landscape but is now in decline [13]. These perceptions may reflect prevailing societal narratives that position certain diversities as more acceptable within institutional environments [68]. Nonetheless, a growing body of research demonstrates that diverse leadership teams—across multiple identity dimensions—can lead to improved organisational outcomes [69,70] which in schools could include higher levels of innovation, better problem-solving, and increased pupil achievement. The limited appreciation for the broader benefits of diversity found in this study indicates a need for further education and advocacy within the sector.

4.4. Tokenism and the Fragility of Trust

Concerns about tokenism were a dominant theme throughout participants’ responses, highlighting the fragility of trust in diversity initiatives. The finding that over 80% of participants agreed that tokenism undermines the credibility of diversity efforts is particularly notable. Tokenism in workplace promotions is often negatively perceived as it can signal symbolic gestures rather than genuine commitment to diversity [71]. When organisations promote individuals from underrepresented groups solely to project inclusivity, it can foster resentment among peers who view such appointments as undeserved [72]. This perception undermines the legitimacy of both the promoted individual and the organisation’s diversity agenda. Moreover, tokenism can contribute to the maintenance of systemic inequalities by masking deeper structural issues and preventing substantive change. Colleagues may also interpret token promotions as anomalies, reinforcing stereotypes and limiting broader acceptance of minority leadership [73,74].

4.5. Lived Experience of Tokens and Their Consequences

For those positioned as tokens, the experience is frequently accompanied by heightened visibility, performance pressure, and isolation. Tokens often feel they must represent their entire identity group, leading to stress and reduced job satisfaction [75]. Their contributions may be scrutinised more closely, and their successes attributed to diversity policies rather than merit, diminishing their professional credibility. Furthermore, token employees can internalise these perceptions, resulting in imposter syndrome and disengagement. Over time, such dynamics can lead to attrition, as individuals opt out of hostile or unsupportive work environments [76]. Perceptions that individuals from minority backgrounds are sometimes promoted merely to fulfil quotas, rather than based on merit, were also prevalent. This reflects tensions identified in other studies, where meritocratic ideals are invoked both to resist and to support diversity initiatives [77].

4.6. Theoretical Lenses: Equity Theory, Organisational Justice Theory, and Legitimacy Theory

The findings can be understood through the intersecting perspectives of equity theory, organisational justice theory, and legitimacy theory, each of which both supports and complicates the interpretation of participants’ views. Equity theory [37] emphasises that fairness is judged by comparing inputs and outcomes, and dissatisfaction arises where perceived imbalances occur. The largely negative net agreement scores for current prioritisation of diversity dimensions resonate with this lens, as many participants appear to perceive that promotions do not adequately reflect the contributions of underrepresented groups. Qualitative comments about candidates being overlooked despite equal or greater inputs exemplify the inequities identified by Adams [37]. At the same time, the strong concern about tokenism challenges equity theory: when diversity measures are seen as privileging certain candidates irrespective of merit, majority-group respondents perceive an imbalance in their own input–outcome ratios. In this sense, equity theory helps to explain both underrepresented participants’ frustration at exclusion and majority participants’ anxieties about unfair advantage, revealing a double-edged tension.

Organisational justice theory [43] similarly aligns with the results. Perceptions of procedural and distributive justice are evident in participants’ references to unclear promotion processes, informal networks, and a lack of transparency. Negative net agreement scores for certain diversity dimensions suggest doubts about the fairness of outcomes, while widespread concern about tokenism reflects anxiety about the legitimacy of processes. Interactional justice is also visible, with participants noting the influence of respect, recognition, and bias in promotional decisions. Yet, the results also highlight a limit of organisational justice theory. While the theory explains dissatisfaction with fairness and transparency, it struggles to account for why some participants reject diversity initiatives even when procedures are transparent, indicating that justice alone may not fully explain resistance.

Legitimacy theory [44,45] provides a broader institutional lens, and here too the results are mixed. On the one hand, participants’ scepticism about tokenism reflects concerns that promotions aimed at symbolic diversity may undermine the legitimacy of leadership. On the other hand, many participants acknowledged that greater diversity could strengthen the credibility of schools. This suggests that legitimacy is fragile: initiatives perceived as imposed or misaligned with prevailing cultural norms risk eroding trust, while those embedded in shared values may reinforce it. Dobbin and Kalev [78] caution that many diversity programmes fail precisely because they rely on coercive, top-down approaches such as mandatory training, testing, or grievance systems, which can provoke backlash and entrench bias rather than reduce it. Their research demonstrates that well-intentioned interventions may inadvertently damage both justice and legitimacy by activating resistance or fostering symbolic agreement.

Taken together, the theories demonstrate why support for diversity coexists with deep anxieties about merit, fairness, and authenticity. They demonstrate that diversity initiatives in education cannot rely solely on policy mandates but must balance equity in outcomes, fairness in processes, and legitimacy in the eyes of all teaching staff.

4.7. Structural and Cultural Barriers in the Irish Context

Structural factors within the Irish education system—such as the predominance of Catholic ethos schools and the historical homogeneity of the teaching workforce—likely compound these perceptions [13,14]. Institutional cultures that favour particular identity profiles can implicitly disadvantage those who do not conform to dominant norms [79]. Given that most survey participants identified as white Irish females, this raises questions about the extent of awareness of systemic barriers among those currently in positions of influence. The observed divergence between participants’ recognition of diversity’s importance and their simultaneous concerns about tokenism reflects a tension between ideals and practical implementation. On one hand, there is support for more representative leadership; on the other, concerns about maintaining standards and ensuring appointments are perceived as legitimate persist.

4.8. Policy and Practice Recommendations

The findings of this study suggest several implications for policy and practice in the Republic of Ireland’s education sector. First, the consistent perception that diversity is not currently prioritised, combined with concerns of tokenism, highlights the need to define merit criteria more clearly in promotion processes. Transparent, competency-based assessments that value a broad range of skills and experiences could help address participants’ concerns about fairness. At the same time, care is needed to avoid reinforcing rigid approaches to merit that may inadvertently privilege dominant norms/groups. Structured training for selection panels can strengthen fairness, but evidence cautions that poorly designed training can sometimes provoke resistance rather than change attitudes [78].

Second, the results revealed a gap between participants’ scepticism about existing prioritisation of diversity and their greater support for whether diversity should be prioritised in the future, particularly regarding gender and cultural or national origin. This suggests that representation is valued in principle, but questions remain about implementation. Policy interventions should therefore move beyond numeric targets to focus on meaningful inclusion, such as leadership development and mentoring programmes for underrepresented groups. These initiatives can build capacity and legitimacy by preparing candidates for senior roles, but they must be resourced and monitored carefully to avoid reinforcing perceptions of token appointments or symbolic compliance.

Finally, the findings pointed to the influence of Ireland’s historically homogenous teaching workforce and the continuing role of Catholic ethos in shaping leadership opportunities. This work can begin in the teacher pipeline and attract students into Initial Teacher Education (ITE) from varying backgrounds. In this context, stakeholder engagement is essential: diversity initiatives will only succeed if they resonate with the lived realities of schools. Developing policy collaboratively with teachers, leaders, and parents can enhance legitimacy and trust, while ensuring sensitivity to the pre-existing norms.

5. Conclusions

This initial exploratory study provides an overview of the perceptions of teachers and school leaders in the Republic of Ireland regarding diversity in promotion to school principalship. The findings reveal disparities between perceived and desired prioritisation of diversity, with disability, social class, and religious diversity being the least prioritised, while gender and cultural diversity receive more support. The mixed views on the impact of diversity on school leadership effectiveness highlight the complexity of integrating diversity into leadership roles. Concerns about tokenism and the authenticity of diversity initiatives underscore the need for transparent and merit-based promotion processes.

The study highlights the importance of aligning diversity initiatives with stakeholder expectations to foster a more inclusive and effective leadership environment in Irish schools. Addressing these challenges requires a multifaceted approach that includes stakeholder engagement, transparent promotion practices, and the creation of organisational cultures where diverse leaders and teachers can thrive.

The limitations of the study must be acknowledged. Although the survey sample was broad in terms of school levels and roles, it remained overwhelmingly white and Irish, potentially constraining the diversity of perspectives captured, but also reflecting the current composition of the Irish school workforce. Furthermore, the reliance on self-report survey data introduces potential biases, such as social desirability effects or misinterpretation of questions [80]. Future research would benefit from triangulating survey findings with qualitative interviews or case studies to explore how diversity dynamics play out within specific school contexts. Comparative studies across other countries would also provide valuable insights into how national contexts shape diversity perceptions.

Despite these limitations, the study offers important insights for policymakers and school leaders seeking to promote diversity within Irish educational leadership. Simply mandating diversity is insufficient. Authentic inclusion requires transparent, fair, and merit-based promotion practices that are perceived as legitimate by all stakeholders. Efforts must extend beyond recruitment to creating organisational cultures where diverse leaders can thrive, contribute meaningfully, and reshape the leadership landscape for future generations.

In conclusion, while there is growing commitment to diversity within school leadership in the Republic of Ireland, substantial work remains to bridge the gap between ambitions and realities. Addressing perceptions of tokenism, clarifying merit criteria, and fostering inclusive organisational cultures will be essential steps towards realising the full potential of a diverse educational leadership. This study provides a foundation for these efforts, highlighting both the opportunities and the challenges that lie ahead.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.H. and N.L.; methodology, R.H. and N.L.; formal analysis, R.H.; investigation, R.H.; writing—original draft preparation, R.H., N.L. and P.M.-M.; writing—review and editing, R.H., N.L. and P.M.-M.; visualization, R.H.; supervision, N.L. and P.M.-M.; project administration, N.L. and P.M.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by a Government of Ireland Postgraduate Scholarship awarded by the Irish Research Council (grant number GOIPG/2024/5169).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The research discussed in this paper received ethical approval from the Education and Health Sciences Ethics Department at University of Limerick on 7 January 2025. Approval number: 2024_12_26_EHS.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request due to restrictions placed on participant privacy; however, segments of the data can be requested by contacting the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Fullan, M. The Principal: Three Keys to Maximizing Impact; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- IPPN. Irish Schools Face Shortage of Principals as Role’s Managerial and Administrative Duties Deter Teachers from Stepping Up to Leadership Role—Education Report; Dublin, Ireland, 2022. Available online: https://www.ippn.ie/index.php/advocacy/press-releases/7225-7-march-2017-irish-schools-face-shortage-of-principals-as-role-s-managerial-and-administrative-duties-deter-teachers-from-stepping-up-to-leadership-role-education-report (accessed on 7 April 2025).

- Leithwood, K.; Jantzi, D. Linking Leadership to Student Learning: The Contributions of Leader Efficacy. Educ. Adm. Q. 2008, 44, 496–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leithwood, K.; Harris, A.; Hopkins, D. Seven strong claims about successful school leadership. Sch. Leadersh. Manag. 2008, 28, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fullan, M. Quality leadership <=> Quality Learning: Proof Beyond Reasonable Doubt; Líonra: Dublin, Ireland, 2006; Available online: https://issuu.com/ippn/docs/qualityleadershipquality_learning-f (accessed on 7 April 2025).

- Beausaert, S.; Froehlich, D.E.; Devos, C.; Riley, P. Effects of support on stress and burnout in school principals. Educ. Res. 2016, 58, 347–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Francesco, F.; Guaschino, E. Reframing knowledge: A comparison of OECD and World Bank discourse on public governance reform. Policy Soc. 2020, 39, 113–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellar, S.; Lingard, B. The OECD and Global Governance in Education. In Testing Regimes, Accountabilities and Education Policy; Lingard, B., Martino, W., Rezai-Rashti, G., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Horwood, M.; Marsh, H.W.; Parker, P.D.; Riley, P.; Guo, J.; Dicke, T. Burning Passion, Burning Out: The passionate school principal, burnout, job satisfaction, and extending the dualistic model of passion. J. Educ. Psychol. 2021, 113, 1668–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krüger, M.L.; van Eck, E.; Vermeulen, A. Why principals leave: Risk factors for premature departure in the Netherlands compared for women and men. Sch. Leadersh. Manag. 2005, 25, 241–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, J.; Dempsey, M. Wellbeing in Post-COVID Schools: Primary School Leaders’ Reimagining of the Future; Maynooth University: Maynooth, Ireland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- McHugh, R. A six-component conceptualization of the psychosocial well-being of school leaders: Devising a framework of occupational well-being for Irish primary principals. Int. J. Leadersh. Educ. 2023, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, M.; James, C.; Murtagh, L. Reflections on recent developments in the governance of schools in Ireland and the role of the church. Manag. Educ. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foxe, K. 97% of People Working in Public Jobs are ‘White Irish’, Research Shows. Available online: https://www.rte.ie/news/business/2024/0624/1456419-97-of-public-jobs-workers-are-white-irish-research/ (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- Devine, D.; Bohnert, M.; Greaves, M.; Ioannidou, O.; Sloan, S.; Martinez-Sainz, G.; Symonds, J.; Moore, B.; Crean, M.; Davies, A.; et al. Children’s School Lives (CSL): National Longitdunal Cohort Study of Primary Schooling in Ireland. Migration and Ethnicity in Children’s School Lives; University College Dublin, School of Education: Dublin, Ireland, 2025; Available online: https://cslstudy.ie/downloads/CSL_8c_Migration-Ethnicity.pdf (accessed on 2 May 2025).

- Central Statistics Office. Census of Population 2022—Summary Results; CSO Statistical Publication: Dublin, Ireland, 2023. Available online: https://www.cso.ie/en/releasesandpublications/ep/p-cpsr/censusofpopulation2022-summaryresults/populationchanges/ (accessed on 12 April 2025).

- Croitoru, G.; Florea, N.V.; Ionescu, C.A.; Robescu, V.O.; Paschia, L.; Uzlau, M.C.; Manea, M.D. Diversity in the Workplace for Sustainable Company Development. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yip, S.Y.; Xu, Y. Increasing the diversity of the teaching workforce: A review of minority teacher candidates’ recruitment, retention, and experiences in initial teacher education. Pedagog. Cult. Soc. 2024, 33, 1687–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travers, J.; King, F. Social justice leadership in Irish schools: Conceptualisations, supports and barriers. Ir. Educ. Stud. 2025, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrone, F. Why a Diverse Leadership Pipeline Matters: The Empirical Evidence. Leadersh. Policy Sch. 2022, 21, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grissom, J.A.; Egalite, A.J.; Lindsay, C.A. How Principals Affect Students and Schools: A Systematic Synthesis of Two Decades of Research; The Wallace Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Leithwood, K. A Review of Evidence about Equitable School Leadership. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bundesamt, S. 24.3% of the Population Had an Immigrant History in 2022. 2022. Available online: https://www.destatis.de/DE/Presse/Pressemitteilungen/2023/04/PD23_158_125.html (accessed on 7 April 2025).

- UK Government, School Workforce in England: Reporting Year 2019. 2020. Available online: https://explore-education-statistics.service.gov.uk/find-statistics/school-workforce-in-England (accessed on 7 April 2025).

- Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership. A.I.f.T.a.S. Spotlight: Building a Sustainable Teaching Workforce. 2022. Available online: https://www.aitsl.edu.au/research/spotlights/building-a-sustainable-teaching-workforce (accessed on 7 April 2025).

- van den Berg, D.; van Dijk, M.; Grootscholte, M. Diversity Monitor 2011—Facts and Figures Concerning Diversity in Primary, Secondary, Vocational and Teacher Education; Education Sector Employment: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Heinz, M. The composition of applicants and entrants to teacher education programmes in Ireland: Trends and patterns. Ir. Educ. Stud. 2008, 27, 223–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinz, M.; Davison, K.; Keane, E. ‘I will do it but religion is a very personal thing’: Teacher education applicants’ attitudes towards teaching religion in Ireland. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 2018, 41, 232–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinz, M.; Keane, E.; Davison, K. Gender in initial teacher education: Entry patterns, intersectionality and a dialectic rationale for diverse masculinities in schooling. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 2021, 46, 134–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinz, M.; Keane, E.; Foley, C. Career Motivations of Student Teachers in the Republic of Ireland: Continuity and Change during Educational Reform and ‘Boom to Bust’ Economic times. In Global Perspectives on Teacher Motivation; Watt, H.M.G., Richardson, P.W., Smith, K., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Keane, E.; Heinz, M. Diversity in initial teacher education in Ireland: The socio-demographic backgrounds of postgraduate post-primary entrants in 2013 and 2014. Ir. Educ. Stud. 2015, 34, 281–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keane, E.; Heinz, M. Excavating an injustice?*: Nationality/ies, ethnicity/ies and experiences with diversity of initial teacher education applicants and entrants in Ireland in 2014. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 2016, 39, 507–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keane, E.; Heinz, M.; Eaton, P. Fit(ness) to teach?: Disability and initial Teacher education in the republic of Ireland. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2017, 22, 819–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forum, N.P. United for Integrity: Recommendations to address the untenable situation of Primary Principals. In Submission from the National Principals’ Forum to the Joint Oireachtas Committee on Education and Skills—August 2018; National Principals’ Forum: Dublin, Ireland, 2018; Available online: https://www.principalsforum.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/NationalPrincipalsForumSubmissionAugust-2018.pdf (accessed on 17 February 2025).

- Stynes, M.; McNamara, G. The challenge of perpetual motion: The willingness and desire of Irish primary school principals to juggle everything. Ir. Educ. Stud. 2018, 38, 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, C. School Principals Say Rising Administration Burden is Affecting Teaching and Learning for Students. The Irish Times, 12 October 2023. Available online: https://www.irishtimes.com/ireland/education/2023/10/12/school-principals-say-rising-administration-burden-is-affecting-teaching-and-learning-for-students/ (accessed on 17 February 2025).

- Adams, J.S. Inequity in Social Exchange. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1965, 2, 267–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jost, J.T. Profiles in Social Justice Research—Elaine Hatfield. Soc. Justice Res. 2008, 21, 409–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castilla, E.J.; Ranganathan, A. The Production of Merit: How Managers Understand and Apply Merit in the Workplace. Organ. Sci. 2020, 31, 909–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scully, M.A. Manage Your Own Employability: Meritocracy and the Legitimacy of Inequality in Internal Labor Markets. In Relational Wealth: The Advantages of Stability in a Changing Economy; Leana, C.R., Rousseau, D.M., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Hannan, R.; Lafferty, N.; Mannix McNamara, P. Leadership Opportunities in the School Setting: A Scoping Study on Staff Perceptions. Societies 2023, 13, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, C.R.; Dover, T.L.; Small, P.; Xia, G.; Brady, L.M.; Major, B. Diversity Initiatives and White Americans’ Perceptions of Racial Victimhood. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2022, 48, 968–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, J. A Taxonomy of Organizational Justice Theories. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1987, 12, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowling, J.; Pfeffer, J. Organizational Legitimacy: Social Values and Organizational Behavior. Pac. Sociol. Rev. 1975, 18, 122–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suchman, M.C. Managing Legitimacy: Strategic and Institutional Approaches. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 571–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chui, C.W.S.; Kleinlogel, E.P.; Dietz, J. Diversity. Wiley Encycl. Manag. 2015, 6, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryman, A. Integrating quantitative and qualitative research: How is it done? Qual. Res. 2006, 6, 97–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, A.; Kale, S.; Chandel, S.; Pal, D. Likert Scale: Explored and Explained. Br. J. Appl. Sci. Technol. 2015, 7, 396–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 8th ed.; Cengage Learning: Andover, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, M.J.; Marshall, A.P. Understanding descriptive statistics. Aust. Crit. Care. 2009, 22, 93–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzahrani, F.; Almutairi, N.; Aloufi, A.; Kattan, A.; Hakeem, A.; Alharbi, M.; Alarawi, N.; Fadil, H.A.; Habeeb, E. Adoption of evidence-based medicine: A comparative study of hospital and community pharmacists in Saudi Arabia. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0324620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haughey, S.; Loughran, T. Public opinion and consociationalism in Northern Ireland: Towards the ‘end stage’ of the power-sharing lifecycle? Br. J. Politics Int. Relat. 2023, 26, 187–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedetti, C. Fighting Fit: Developing Racially Diverse Principal Pathways in Historically Homogeneous Communities. J. Educ. Leadersh. Policy Stud. 2022, 6, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer, R.; Jacobs, R.; Tuxworth, J.; Qi, J.; Harris, D.X.; Manathunga, C. Schools as inclusive workplaces: Understanding the needs of a diverse teaching workforce in Australian schools. Aust. Educ. Res. 2024, 52, 765–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, L.; Lengyel, D. Research on Minority Teachers in Germany: Developments, Focal Points and Current Trends from the Perspective of Intercultural Education; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worth, J.; McLean, D.; Sharp, C. Racial Equality in the Teacher Workforce: An Analysis of Representation and Progression Opportunities from Initial Teacher Training to Headship; National Foundation for Educational Research: Slough, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher, L.; Beauregard, A.T. The psychology of diversity and its implications for workplace (in)equality: Looking back at the last decade and forward to the next. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2022, 95, 577–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, M.K. Addressing workplace gender inequality: Using the evidence to avoid common pitfalls. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2023, 62, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Héliot, Y.G.; Gleibs, I.; Coyle, A.; Rousseau, D.M. Religious identity in the workplace: A systematic review, research agenda, and practical implications. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2019, 59, 153–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrotty, C. How Inclusive are Diversity and Inclusion Strategies for People with Disabilities in the Workplace? Ahead J. A Rev. Incl. Educ. Employ. Pract. 2021, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Priola, V.; Lasio, D.; Serri, F.; De Simone, S. The organisation of sexuality and the sexuality of organisation: A genealogical analysis of sexual ‘inclusive exclusion’ at work. Organization 2018, 25, 732–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maji, S.; Yadav, N.; Gupta, P. LGBTQ+ in workplace: A systematic review and reconsideration. Equal. Divers. Incl. Int. J. 2023, 43, 313–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köllen, T. Bisexuality and diversity management—Addressing the B in LGBT as a relevant ‘sexual orientation’ in the workplace. J. Bisexuality 2013, 13, 122–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewis, J.; Sinclair, J. Exploring embodiment: Women, biology and work. In Body and Organization; Sage Publishing: London, UK, 2020; pp. 192–214. [Google Scholar]

- Colgan, F.; Rumens, N. Sexual Orientation at Work: Contemporary Issues and Perspectives; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Compton, C.A.; Doughtery, D.A. Organizing Sexuality: Silencing and the Push–Pull Process of Co-sexuality in the Workplace. J. Commun. 2017, 67, 874–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNulty, Y.; McPhail, R.; Inversi, C.; Dundon, T.; Nechanska, E. Employee voice mechanisms for lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender expatriation: The role of employeeresource groups (ergs) and allies. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2018, 29, 829–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brimhall, K.C.; Fenwick, K.; Farahnak, L.R.; Hurlburt, M.S.; Roesch, S.C.; Aarons, G.A. Leadership, Organizational Climate, and Perceived Burden of Evidence-Based Practice in Mental Health Services. Adm. Policy Ment. Health Ment. Health Serv. Res. 2015, 43, 629–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makkonen, F. Board diversity and firm innovation: A meta-analysis. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2022, 25, 941–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kataria, A.; Kumar-Verma, M. Perceived Tokenism and Its Impact on Employee Morale and Job Satisfaction: A Study in Corporate Workplaces. Libr. Prog. Int. 2023, 43. [Google Scholar]

- Danaher, K.; Branscombe, N.R. Maintaining the system with tokenism: Bolstering individual mobility beliefs and identification with a discriminatory organization. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 49, 343–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanter, R.M. Men and Women of the Corporation; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Yoder, J.D. Rethinking Tokenism: Looking beyond Numbers. Gend. Soc. 1991, 5, 178–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holgersson, C.; Romani, L. Tokenism Revisited: When Organizational Culture Challenges Masculine Norms, the Experience of Token Is Transformed. Eur. Manag. Rev. 2020, 17, 649–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gullifor, D.P.; Gardner, W.L.; Karam, E.P.; Noghani, F.; Cogliser, C.C. The impostor phenomenon at work: A systematic evidence-based review, conceptual development, and agenda for future research. J. Organ. Behav. 2023, 45, 234–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foley, M.; Cooper, R.; Colley, L.; Williamson, S. Best person or best mix? How public sectormanagers understand the merit principle. Aust. J. Public Adm. 2022, 81, 401–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobbin, F.; Kalev, A. Why Diversity Programs Fail. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2016. Available online: https://hbr.org/2016/07/why-diversity-programs-fail (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Banaji, M.R.; Fiske, S.T.; Massey, D.S. Systemic racism: Individuals and interactions, institutions and society. Cogn. Res. Princ. Implic. 2021, 6, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caputo, A. Social desirability bias in self-reported well-being measures: Evidence from an online survey. Univ. Psychol. 2017, 16, 245–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).