Disabling Norms, Affirming Desires: A Scoping Review on Disabled Women’s Sexual Practices

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

- Identifying the research question;

- Identifying relevant studies for the review;

- Selecting studies to include in the analysis;

- Charting the data extracted from each article;

- Collating, summarizing, and reporting the results.

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

- Explores the sexual practices of disabled women;

- Includes cis-heterosexual and/or queer disabled women in the study sample;

- Employed a quantitative, qualitative, or mixed-methods research design;

- Published between 1 January 2013 and 31 December 2023;

- Available in Portuguese, English, or Spanish.

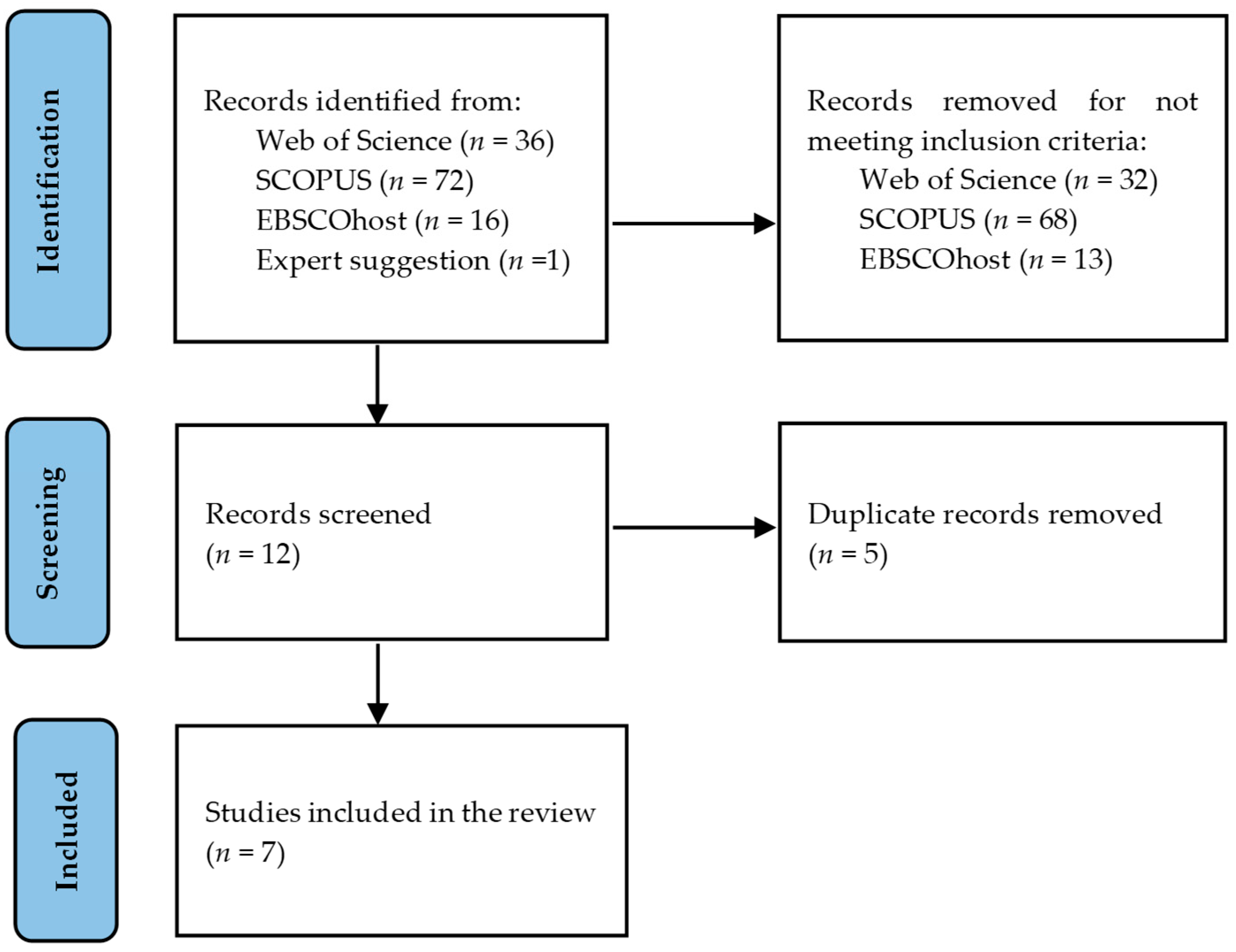

2.3. Search Strategy

2.4. Data Extraction and Analysis

- Author(s);

- Year of publication;

- Research aim(s);

- Participants;

- Context;

- Study design;

- Main findings.

- Becoming familiar with the data through the integral reading of the articles that served as a corpus for the analysis, while elaborating a list of initial ideas with possible meanings on the data and filling the data charting form;

- Identifying all aspects of each article relevant to the research question, inclusively and exhaustively, and assigning them a code;

- Aggregating codes with the same or related meanings into potential themes;

- Reviewing and refining the initial themes to ensure compliance with the homogeneity and mutual exclusion criteria;

- Naming and clearly defining the themes;

- Producing the scoping review output for results dissemination.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Reclaiming Sexuality: Breaking Stereotypes Through Agency

I stuck a meat fork into a carrot and covered the carrot in Saran Wrap to have some penetration (…) I had to organize things (…) and later, at the age of 43, I found a sex toy in a sex shop to stimulate the clitoris with different vibrations, so I took a long spaghetti fork and taped it onto it so I could use it with my hands [32] (p. 310).

There was this phase of a new exploration of sexuality with a new body or with a body that had differences, and I remember there were some positions that I couldn’t take …And yet, today I can say that I don’t feel limited because we always find alternatives [laughs] and because everything is done, even if it’s done differently from what we’re used to …I like the position in which the man is behind …and it was not possible, because as I’m amputated above the knee there aren’t two knees …And yet I found it was as simple as putting two or three pillows underneath [laughs]! But it wasn’t as immediate as that. There was some frustration and sadness [10] (p. 9).

3.2. Navigating Constraints: Cultural, Institutional, and Legal Factors

A person like me has to overcome several difficulties. First, those around have to notice that a person in a wheelchair is a person, then an adult, and then that the person is a woman, and then, that the person is non-heteronormative [35] (p. 782).

I was sent to a psychologist. I just told her I had a girlfriend […]. I was called to the principal’s office, and they asked me whether I was a lesbian, which I thought was quite shocking at the time. And when I nodded, I had to sign a letter that I would go for treatment […]—it was something like conversion therapy [35] (p. 785).

3.3. Barriers to Awareness: Sex Education and Specialized Training Deficiencies

I felt like a real idiot compared to other people, lots of them are younger than me, then someone was talking about the G spot and I had no idea what it was (…) I don’t even know where the clitoris is [32] (p. 308).

I found an absolute ignorance amongst gynaecologists about sexuality of disabled women, particularly spinal cord injuries acquired. In their minds we have no pleasure, nor should we have children, because it only gets complicated, due to their misinformation. For example, I had to educate my gynaecologist about this matter. And concerning psychologists and psychiatrists, it is the same. It remains a taboo subject [10] (p. 6).

3.4. Building Inclusive Futures

[…] people with disabilities must have access to sexual education that meets their specific needs. We also believe that a specific recognition of their needs must be applied when education programs are being formulated so they can develop sexual skills to meet those needs [32] (p. 312).

The creation of an expanded discourse on sexuality and more egalitarian modes of expression in rehabilitation institutions, as well as in the general public, are necessary and could be made possible through the use of technology (websites, mobile applications, virtual reality, etc.). Another solution might be the creation of specialized technical aids or sex toys [31] (p. 428).

[…] the fact that sex workers’ services are not legalized in our society or are otherwise controversial, makes some people reluctant to use them. As for the biopsychosocial benefits of masturbation, this study also observed that this activity can improve health, foster bodily learning and enhance body image [31] (p. 427).

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Sexual citizenship integrates sexual rights into the broader framework of citizenship. This concept emphasizes people’s ability to express their sexuality and make informed decisions regarding sexual identity, relationships, and health; recognizes sexual diversity and the safeguarding of sexual rights, particularly for marginalized groups; and underscores the principles of sexual autonomy, equality, and participation in sexual life, free from discrimination and exclusion [5,6]. Sexual citizenship draws attention to the structural inequalities that influence sexual experiences, advocating for social justice to ensure people’s fundamental sexual rights. |

| 2 | Romañach and Lobato [27] proposed “functional diversity” as a linguistic shift to refer to the natural variation in how human beings interact with their environment, encompassing physical, sensory, intellectual, and psychological differences. This terminology moves beyond medicalized or deficit-focused language, like disability, and frames diversity as a normal and dignified part of human existence. More common in Spain and Portugal, functional diversity aligns with a rights-based approach, emphasizing autonomy, social inclusion, and dismantling barriers imposed by structural ableism. By focusing on functionality as a spectrum rather than categorizing individuals based on impairments, this concept seeks to foster respect, equity, and recognition of individual capabilities. |

References

- World Health Organization. Defining Sexual Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/sexual-and-reproductive-health-and-research/key-areas-of-work/sexual-health/defining-sexual-health (accessed on 3 April 2025).

- Plan International. Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights: Plan International’s Position Statement. 2016. Available online: https://plan-international.org/publications/sexual-reproductive-health-rights (accessed on 3 April 2025).

- International Planned Parenthood Federation. Sexual Rights: An IPPF Declaration. 2008. Available online: https://www.ippf.org/resource/sexual-rights-ippf-declaration (accessed on 3 April 2025).

- World Association for Sexual Health. Declaration of Sexual Rights. 2014. Available online: https://www.worldsexualhealth.net/was-declaration-on-sexual-rights (accessed on 3 April 2025).

- Richardson, D. Rethinking Sexuality; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Weeks, J. The sexual citizen. Theory Cult. Soc. 1998, 15, 35–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakespeare, T.; Gillespie-Sells, K.; Davies, D. The Sexual Politics of Disability: Untold Desires; Cassell: Sydney, Australia, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Shuttleworth, R.P. The search for sexual intimacy for men with cerebral palsy. Sex. Disabil. 2000, 18, 263–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmail, S.; Dary, K.; Walter, A.; Knupp, H. Attitudes and perceptions towards disability and sexuality. Disabil. Rehabil. 2010, 32, 1148–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, A.C.; Santos, A.L. Yes, we fuck! Challenging the misfit sexual body through disabled women’s narratives. Sexualities 2018, 21, 303–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulick, D.; Rydström, J. Loneliness and Its Opposite; Duke University Press: Durham, NC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Roseneil, S.; Crowhurst, I.; Hellesund, T.; Santos, A.C.; Stoilova, M. The Tenacity of the Couple-Norm: Intimate Citizenship Regimes in a Changing Europe; UCL Press: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, A.C.; Fontes, F.; Martins, B.S.; Santos, A.L. Mulheres, Sexualidade, Deficiência: Os Interditos da Cidadania Íntima; Almedina: Coimbra, Portugal, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, H. ‘An ordinary sexual life?’: A review of the normalisation principle as it applies to the sexual options of people with learning disabilities. Disabil. Soc. 1994, 9, 123–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, M. The politics of disability and feminism: Discord or synthesis? Sociology 2001, 35, 715–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN General Assembly. United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, 13 December 2006, A/RES/61/106. Available online: http://undocs.org/en/A/RES/61/106 (accessed on 3 April 2025).

- Vaughn, M.; McEntee, B.; Schoen, B.; McGrady, M. Addressing Disability Stigma within the Lesbian Community. J. Rehabil. 2015, 81, 49–56. [Google Scholar]

- Keates, N.; Dewar, E.; Waldock, K.E. “Lost in the literature.” People with intellectual disabilities who identify as trans: A narrative review. Tizard Learn. Disabil. Rev. 2022, 27, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harner, V.; Johnson, I.M. At the intersection of trans and disabled. In Social Work and Health Care Practice with Transgender and Nonbinary Individuals and Communities; Routledge: London, UK, 2020; pp. 359–372. [Google Scholar]

- Earle, S.; O’Dell, L.; Davies, A.; Rixon, A. Views and Experiences of Sex, Sexuality and Relationships Following Spinal Cord Injury: A Systematic Review and Narrative Synthesis of the Qualitative Literature. Sex. Disabil. 2020, 38, 567–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matin, B.K.; Ballan, M.; Darabi, F.; Kazemi Karyani, A.; Soofi, M.; Soltani, S. Sexual Health Concerns in Women with Intellectual Disabilities: A Systematic Review in Qualitative Studies. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naghdi-Dorabati, P.; Shahali, S.; Montazeri, A.; Ahmadi, F. The Unmet Need for Sexual Health Services among Women with Physical Disabilities: A Scoping Review. J. Public Health 2024. [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H.; McInerney, P.; Parker, D.; Soares, C.B. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. JBI Evid. Implement. 2015, 13, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, C. Interseccionalidade e psicologia feminista; Editora Devires: Bahia, Brazil, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Romañach, J.; Lobato, M. Functional diversity, a new term in the struggle for dignity in the diversity of the human being. In Independent Living Forum; European Network on Independent Living: Valencia, Spain, 2005; Volume 5, pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. health 2019, 11, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fish, R. ‘They’ve said I’m vulnerable with men’: Doing sexuality on locked wards. Sexualities 2016, 19, 641–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, E.; Gauthier, V.; Edwards, G.; Courtois, F. Masturbation practices of men and women with upper limb motor disabilities. Sex. Disabil. 2016, 34, 417–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, E.; Gauthier, V.; Edwards, G.; Courtois, F. Women with disabilities’ perceptions of sexuality, sexual abuse and masturbation. Sex. Disabil. 2016, 34, 303–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, D.A.; Hickey, H.; Nelson, A.; Rees, K.; Bollinger, H.; Hartley, S. Physically disabled women and sexual identity: A PhotoVoice study. Disabil. Soc. 2016, 31, 1030–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peta, C.; McKenzie, J.; Kathard, H. Voices from the periphery: A narrative study of the experiences of sexuality of disabled women in Zimbabwe. Agenda 2015, 29, 66–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wołowicz, A.; Król, A.; Struzik, J. Disabled women, care regimes, and institutionalised homophobia: A case study from Poland. Sex. Res. Soc. Policy 2022, 19, 777–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakespeare, T. The sexual politics of disabled masculinity. Sex. Disabil. 1999, 17, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rainey, S.S. Love, Sex, and Disability: The Pleasures of Care; Lynne Rienner Publishers: Boulder, CO, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- European Network on Independent Living. Independent Living. 2022. Available online: https://enil.eu/independent-living/ (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Inckle, K.; Brighton, J.; Sparkes, A. Who Is “Us” in “Nothing About Us Without Us”? Rethinking the Politics of Disability Research. Disabil. Stud. Q. 2023, 42, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author(s) | Year | Objectives | Participants | Context | Study Design | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fish [30] | 2016 | Explore sexuality among intellectually disabled women living in a secure unit. | 16 intellectually disabled women aged 18–60, and 10 staff members. | North England | Ethnographic, in-depth interviews, participant observation. |

|

| Morales et al. [31] | 2016 | Document masturbation practices and sexual experiences of physically disabled men and women. | 18 participants (10 men, 8 women); aged 18+; heterosexual and gay; physically disabled without cognitive impairments. | Quebec, Canada | Qualitative, semi-structured interviews, NVivo analysis. |

|

| Morales et al. [32] | 2016 | Explore disabled women’s sexual experiences, perceptions of sexuality, and abuse. | 8 heterosexual physically disabled women, aged 18+, without cognitive impairments. | Quebec, Canada | Qualitative, semi-structured interviews, NVivo analysis. |

|

| Payne et al. [33] | 2016 | Examine young physically disabled women’s perspectives on sexuality and identity. | Four congenitally disabled women, aged 18–32, and three wheelchair users. | Auckland, New Zealand | Qualitative, participatory action research (PhotoVoice). |

|

| Peta et al. [34] | 2015 | Explore how disability intersects with gender, cultural norms, and sexual experiences of women. | A 38-year-old Zimbabwean woman with polio, mother of two sons, HIV-positive. | Harare, Zimbabwe | Qualitative, biographical narrative interpretive method. |

|

| Santos & Santos [10] | 2018 | Examine the social and cultural contexts of sexual experiences and desires of disabled women. | 30 Portuguese white disabled women, aged 29–49, mostly heterosexual, non-practicing Catholics. | Portugal | Qualitative, feminist disability studies, biographical narrative |

|

| Wolowicz et al. [35] | 2022 | Investigate how non-heterosexual disabled women navigate care regimes and homophobia in institutional and non-institutional settings. | 11 non-heterosexual congenitally physically disabled women, aged 30–47, mostly tertiary educated, with experiences in same-sex relationships. | Poland | Qualitative, Narrative analysis, NVivo, semi-structured interviews. |

|

| Themes | Records Included |

|---|---|

| Reclaiming Sexuality: Breaking Stereotypes through Agency | [10,30,31,32,33,34,35] |

| Navigating Constraints: Cultural, Institutional, and Legal Factors | [10,30,31,32,33,34,35] |

| Barriers to Awareness: Sex Education and Specialized Training Deficiencies | [10,30,31,32,33,35] |

| Building Inclusive Futures | [10,30,31,32,35] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Silva, I.; Santos, A.C.; Oliveira, A. Disabling Norms, Affirming Desires: A Scoping Review on Disabled Women’s Sexual Practices. Societies 2025, 15, 154. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15060154

Silva I, Santos AC, Oliveira A. Disabling Norms, Affirming Desires: A Scoping Review on Disabled Women’s Sexual Practices. Societies. 2025; 15(6):154. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15060154

Chicago/Turabian StyleSilva, Inês, Ana Cristina Santos, and Alexandra Oliveira. 2025. "Disabling Norms, Affirming Desires: A Scoping Review on Disabled Women’s Sexual Practices" Societies 15, no. 6: 154. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15060154

APA StyleSilva, I., Santos, A. C., & Oliveira, A. (2025). Disabling Norms, Affirming Desires: A Scoping Review on Disabled Women’s Sexual Practices. Societies, 15(6), 154. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15060154