Human Resource Management in Industry 4.0 Era: The Influence of Resilience and Self-Efficacy on the Relationship Between Emotional Intelligence and Formative Assessment: A Study of Public Primary Educational Organizations

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Human Resource Management in the Industry 4.0 Era

1.2. Educational Leadership in Post-COVID Era

2. Literature Review

2.1. Human Resource Management, Educational Leadership, and Formative Assessment

2.2. Emotional Intelligence and Its Relationship with Formative Assessment, Resilience, and Self-Efficacy

2.3. Self-Efficacy and Its Relationship with Resilience

2.4. Resilience and Its Relationship with Formative Assessment

2.5. Self-Efficacy and Its Relationship with Formative Assessment

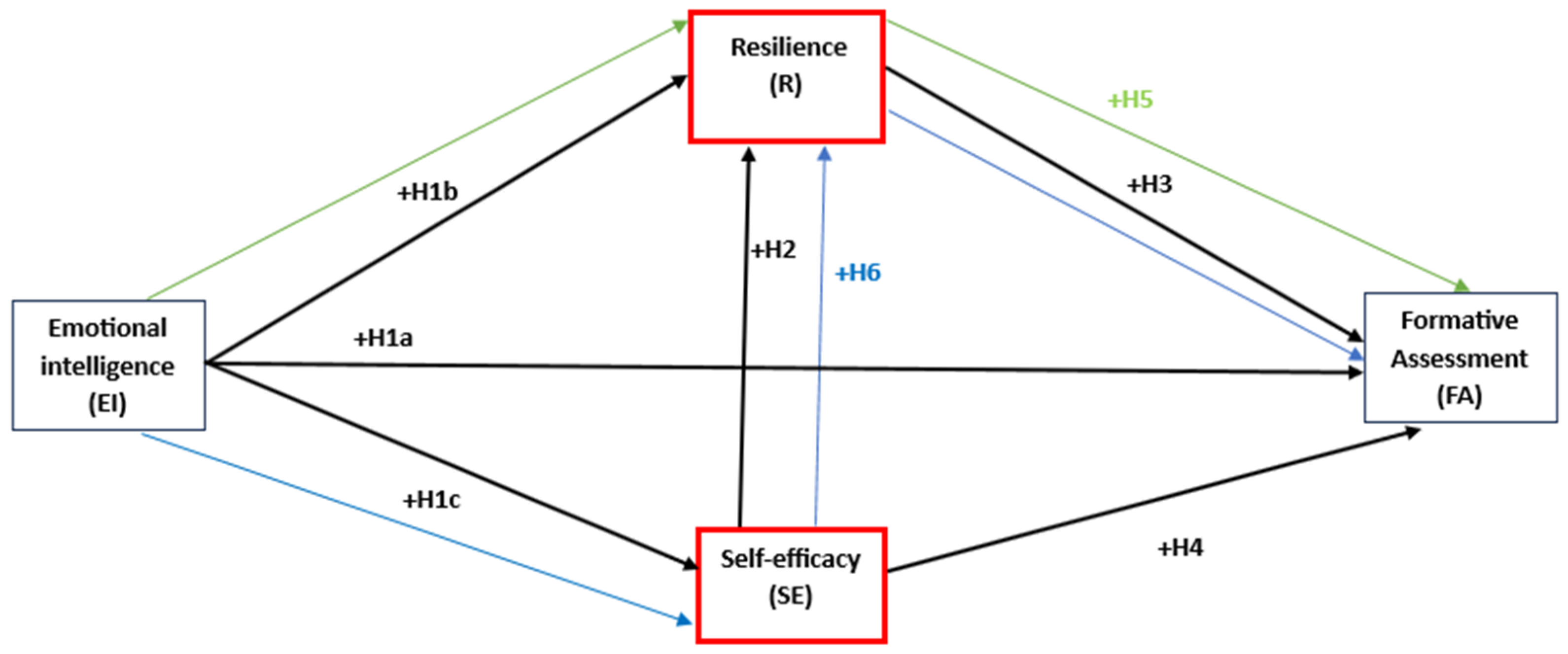

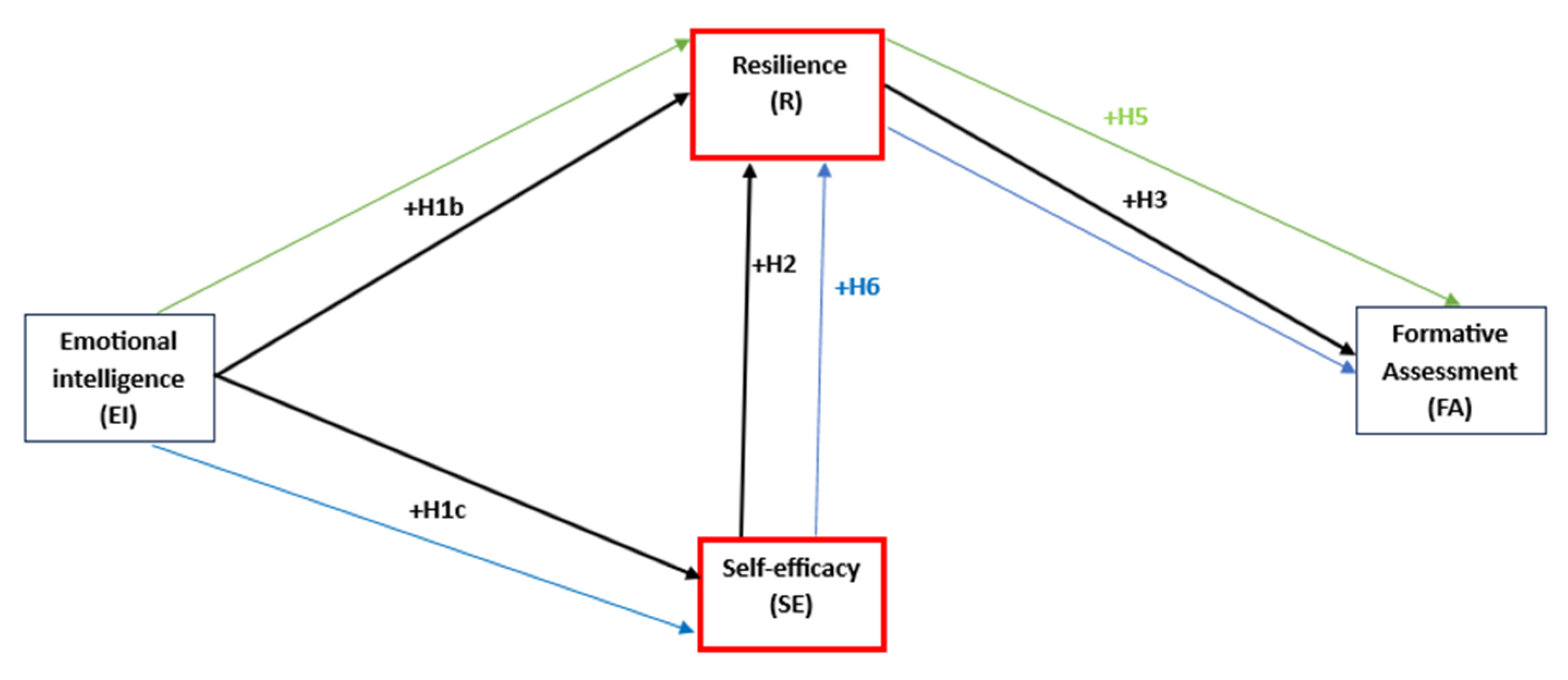

2.6. Resilience and Self-Efficacy as Mediators Between Emotional Intelligence and Formative Assessment

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Participants and Sample Descriptives

3.2. Measurement Tools and Data Collection

3.3. Statistical Analysis

3.4. Reliability and Validity of the Measurement Model

4. Results

4.1. Structural Model Analysis

4.2. Hypothesis Testing Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sofijanova, E.; Andronikov, D. Koмпoнeнти Ha Oпepaтивнo Hивo Ha Meнaџмeнт. Yearb.-Fac. Econ. 2021, 22, 51–55. [Google Scholar]

- Zolak Poljašević, B.; Gričnik, A.M.; Šarotar Žižek, S. Human Resource Management in Public Administration: The Ongoing Tension Between Reform Requirements and Resistance to Change. Adm. Sci. 2025, 15, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillai, R.; Paul, B. Industry 4.0 and the changing employment relations: A case of the Indian information technology industry. NHRD Netw. J. 2023, 16, 92–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troth, A.C.; Guest, D.E. The case for psychology in human resource management research. Hum. Res. Manag. J. 2020, 30, 34–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, M.F.N.; Mahmud, R.; Hidayati, R.; Lataruva, E. The Role of Emotional Intelligence and Self-Efficacy in Enhancing Employee Performance: A Systematic Literature Review. Res. Horiz. 2024, 4, 183–194. [Google Scholar]

- Koutroukis, T.; Chatzinikolaou, D.; Vlados, C.; Pistikou, V. The Post—COVID-19 Era, Fourth Industrial Revolution, and New Globalization: Restructured Labor Relations and Organizational Adaptation. Societies 2022, 12, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bikse, V.; Grinevica, L.; Rivza, B.; Rivza, P. Consequences and Challenges of the Fourth Industrial Revolution and the Impact on the Development of Employability Skills. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tusquellas, N.; Palau, R.; Santiago, R. Analysis of the Potential of Artificial Intelligence for Professional Development and Talent Management: A Systematic Literature Review. Int. J. Inf. Manag. Data Insights 2024, 4, 100288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asemota, M.O.; Owoeye, G. Integrating Human-Centric AI into Corporate Learning: Balancing Automation with Empathy. Dev. Learn. Organ. Int. J. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amy, A.H. Leaders as Facilitators of Individual and Organizational Learning. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2008, 29, 212–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, N.; Hirudayaraj, M. The Role of Leader Emotional Intelligence in Organizational Learning: A Literature Review Using 4I Framework. New Horiz. Adult Educ. Hum. Resour. Dev. 2021, 33, 51–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barile, S.; Ciasullo, M.V.; Testa, M.; La Sala, A. An Integrated Learning Framework of Corporate Training System: A Grounded Theory Approach. TQM J. 2023, 35, 1106–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borde, P.S.; Arora, R.; Kakoty, S. Leadership in Higher Educational Institutions Post 2020: Probing Effect of Pandemic and ICT. Eur. J. Educ. 2024, 59, e12680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jogezai, N.A.; Baloch, F.A. COVID-19 and School Leadership: A Tale of Transition. Int. J. Leadersh. Educ. 2024, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Teachers and Leaders in Schools: Supporting Effective Teaching and Learning. 2023. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/education/teachers/ (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Cortez Ochoa, A.A.; Thomas, S.M.; Moreno Salto, I. Teacher and Headteacher Assessment, Feedback, and Continuing Professional Development: The Mexican Case. Assess. Educ. 2023, 30, 273–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berisha, F.; Vula, E.; Gisewhite, R.; McDuffie, H. The Effectiveness and Challenges Implementing a Formative Assessment Professional Development Program. Teach. Dev. 2024, 28, 19–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofijanova, E.; Manev, M. Ability, Motivation and Employe Work Behaviors. J. Econ. 2020, 5, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karanikola, M.; Georganta, K.; Kaikoushi, K.; Koutroubas, V.S.; Kalafati, D. Qualitative Inquiry into Work-Related Distressing Experiences in Primary School Educational managers. Societies 2025, 15, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukandar, A. The Role of Leadership and Motivation of School Headmaster in Improving Teacher Performance. Int. J. Nusant. Islam 2018, 6, 182–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amrullah, S.; Ardiansyah, M.L. Sumarto Managerial Capabilities of Headmaster in Improving Teacher Performance. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Education and Multimedia Technology—ICEMT 2019, Nagoya, Japan, 22–25 July 2019; ACM Press: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lasuhu, A.R. Headmaster Evaluation of Teacher Performance Improvement in Madrasah Aliyah Swasta (Mas) Al Ma’arif Jikotamo. INCARE Int. J. Educ. Resour. 2023, 4, 043–054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Painter, S.R. Educational managers’ Efficacy Beliefs about Teacher Evaluation. J. Educ. Adm. 2000, 38, 368–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonner, S.M. Teachers’ Perceptions about Assessment: Competing Narratives. In Handbook of Human and Social Conditions in Assessment; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; pp. 21–39. [Google Scholar]

- Lau, A.M.S. ‘Formative Good, Summative Bad?’—A Review of the Dichotomy in Assessment Literature. J. Furth. High. Educ. 2016, 40, 509–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zou, J.; Ge, Q.; Song, S.A. Bibliometric Analysis of the Psychologization of Human Resource Management. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2023, 34, 650–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, J. Leadership Potential: Measurement Beyond Psychometrics; The British Psychological Society: London, UK, 2020; Volume 12. [Google Scholar]

- Mulvale, S.; Teo, T. Psychologization and its vicissitudes. In Psychologie und Kritik; Balz, V., Malich, L., Eds.; Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2020; pp. 43–58. [Google Scholar]

- Yarbrough, D.B.; Shulha, L.M.; Hopson, R.K.; Caruthers, F.A. The Program Evaluation Standards: A Guide for Evaluators and Evaluation Users, 3rd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2010; pp. 278–285. [Google Scholar]

- Brookhart, S.M.; Nitko, A.J. Educational Assessment of Students, 8th ed.; Pearson College Div: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 152–165. [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson, M.L.; Mavrogordato, M.; Youngs, P.; Dougherty, S.M. Principals’ Priorities, Teacher Evaluation, and Instructional Leadership. Educ. Res. 2024, 53, 487–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellibaş, M.Ş.; Polatcan, M.; Alzouebi, K. Instructional Leadership and Student Achievement across UAE Schools: Mediating Role of Professional Development and Cognitive Activation in Teaching. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2025, 17411432241305702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhadra, M. Human Resources for Quality Management in School Education: Managerial Leadership Towards Development of Leaders. Int. Multidiscip. Res. J. 2024, 6, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Oikonomidou, M.; Konstantinidis, I. The Impact of HRM Practices to Employees’ Satisfaction and Organizational Performance in Public Administration: The Case of the Administration Services of Education in the Region of North Greece. Public Policy Bg 2019, 10, 103–120. [Google Scholar]

- Jahidin, N. The Role of Senior Leader Team on the Formative Assessment Practices among Primary School Teachers in Petaling. Ph.D. Thesis, Universiti Teknologi Mara (Kampus Puncak Alam), Puncak Alam, Malaysia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Garrett, J.M.; Camper, J.M. Formative Assessment as an Effective Leadership Learning Tool. New Dir. Stud. Leadersh. 2015, 2015, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattie, J.; Timperley, H. The Power of Feedback. Rev. Educ. Res. 2007, 77, 81–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wisniewski, B.; Zierer, K.; Hattie, J. The Power of Feedback Revisited: A Meta-Analysis of Educational Feedback Research. Front. Psychol. 2020, 10, 487662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triantafillidou, E.; Koutroukis, T. Employee Involvement and Participation as a Function of Labor Relations and Human Resource Management: Evidence from Greek Subsidiaries of Multinational Companies in the Pharmaceutical Industry. Adm. Sci. 2022, 12, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triantafillidou, E.; Koutroukis, T. Human Resource Management, Employee Participation and European Works Councils: The Case of Pharmaceutical Industry in Greece. Societies 2022, 12, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quirós-Alpera, S.; Roets, A.O.; Robina-Ramírez, R.; Leal-Solís, A. Bridging Theory and Practice: Challenges and Opportunities in Dual Training for Sustainability Education at Spanish Universities. Societies 2025, 15, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, R. The Mediating Role of Emotional Intelligence between Self-Efficacy and Resilience in Chinese Secondary Vocational Students. Front. Psychiatry 2024, 15, 1382881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merzaq, B.; El Hajjami, A.; Rkiai, M. The predictive role of emotional intelligence in psychological resilience among Moroccan baccalaureate students. J. Qual. Educ. 2024, 14, 120–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabregas, S.R.; Tamayo, A.R.R.; Villanueva, K.J.E.; Aguila, J.R.S. Emotional Intelligence and Mathematical Resilience of Pre-Service Teachers. Community Soc. Dev. J. 2025, 26, 84–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social Cognitive Theory of Self-Regulation. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 248–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrat, O. Knowledge Solutions; Springer: Singapore, 2017; pp. 329–339. [Google Scholar]

- Palmucci, D.N.; Giovando, G.; Vincurova, Z. The Post-Covid Era: Digital Leadership, Organizational Performance and Employee Motivation. Manag. Decis. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Jones, L.M. Managing to Care, the Emotional Dimensions of Formative Assessment: Sustainability of Teacher Learner Relationships in Four Case Studies. Ph.D. Thesis, UCL (University College London), London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Garibello, C.; Young, M. Emotions and Assessment: Considerations for Rater-Based Judgements of Entrustment. Med. Educ. 2018, 52, 254–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychological Association 2014—The Road to Resilience. Available online: https://www.apa.org/topics/resilience (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Hassan, N.M.; Daud, N.; Mahdi, N.N.R.N.; Ibrahim, M.S.; Yusop, Y.M.; Pauzi, M.F. Modifiable Factors Influencing Emotional Intelligence among Medical Interns. BJPsych Open 2022, 8, S29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozo-Rico, T.; Poveda, R.; Gutiérrez-Fresneda, R.; Castejón, J.-L.; Gilar-Corbi, R. Revamping Teacher Training for Challenging Times: Teachers’ Well-Being, Resilience, Emotional Intelligence, and Innovative Methodologies as Key Teaching Competencies. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2023, 16, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, R.; Zeb, S.; Nisar, F.; Yasmin, F.; Poulova, P.; Haider, S.A. The Impact of Emotional Intelligence on Career Decision-Making Difficulties and Generalized Self-Efficacy Among University Students in China. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2022, 15, 865–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valente, S.; Veiga-Branco, A.; Rebelo, H.; Lourenço, A.A.; Cristóvão, A.M. The Relationship between Emotional Intelligence Ability and Teacher Efficacy. Univers. J. Educ. Res. 2020, 8, 916–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostić-Bobanović, M. Perceived Emotional Intelligence and Self-Efficacy among Novice and Experienced Foreign Language Teachers. Econ. Res.-Ekon. Istraz. 2020, 33, 1200–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chust-Hernández, P.; López-González, E.; Senent-Sánchez, J.M. Study Skills Intervention Addressing Academic Stress and Self-Efficacy in Newly Admitted University Students. Electron. J. Res. Educ. Psychol. 2024, 22, 533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniilidou, A.; Platsidou, M.; Gonida, E. Primary School Teachers Resilience: Association with Teacher Self-Efficacy, Burnout and Stress. Electron. J. Res. Educ. Psychol. 2020, 18, 549–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozdemir, C.; Kaplan, A. Factors affecting psychological resilience, self-efficacy and job satisfaction of nurse academics: A cross-sectional study. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2025, 72, e13007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthar, S.S. Resilience in Development: A Synthesis of Research across Five Decades. In Developmental Psychopathology; Cicchetti, D., Cohen, D.J., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; Volume 3, pp. 739–795. [Google Scholar]

- Reyes, J.A.; Elias, M.J. Fostering Social–Emotional Resilience among Latino Youth. Psychol. Sch. 2011, 48, 723–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resilience Research Centre 2014—Resilience Research, Tools & Resources. Available online: https://resilienceresearch.org/ (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Mansfield, C.F.; Beltman, S.; Broadley, T.; Weatherby-Fell, N. Building Resilience in Teacher Education: An Evidenced Informed Framework. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2016, 54, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Q.; Day, C. Challenges to Teacher Resilience: Conditions Count. Br. Educ. Res. J. 2013, 39, 22–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H. Teacher Learning Opportunities Provided by Implementing Formative Assessment Lessons: Becoming Responsive to Student Mathematical Thinking. Int. J. Sci. Math. Educ. 2019, 17, 341–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Li, Z.; Panadero, E.; Yang, M.; Yang, L.; Lao, H. A Systematic Review on Factors Influencing Teachers’ Intentions and Implementations Regarding Formative Assessment. Assess. Educ. 2021, 28, 228–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Cheng, E.C.K. Primary Teachers’ Attitudes, Intentions and Practices Regarding Formative Assessment. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2015, 45, 128–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM). Available online: https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/a-primer-on-partial-least-squares-structural-equation-modeling-pls-sem/book270548 (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Ngui, G.K.; Lay, Y.F. The Predicting Roles of Self-Efficacy and Emotional Intelligence and the Mediating Role of Resilience on Subjective Well-Being: A PLS-SEM Approach. Pertanika J. Soc. Sci. Hum. 2019, 27, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Petrides, K.V.; Furnham, A. Trait Emotional Intelligence: Psychometric Investigation with Reference to Established Trait Taxonomies. Eur. J. Pers. 2001, 15, 425–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrides, K.V.; Furnham, A. Trait Emotional Intelligence: Behavioural Validation in Two Studies of Emotion Recognition and Reactivity to Mood Induction. Eur. J. Pers. 2003, 17, 39–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrides, K.V.; Furnham, A. Technical Manual for the Trait Emotional Intelligence Questionnaires (TEIQue), 3rd ed.; London Psychometric Laboratory: London, UK, 2009; pp. 59–63. [Google Scholar]

- Mansfield, C.F.; Wosnitza, M. Teacher Resilience Questionnaire—Version 1.5; Murdoch University, RWTH Aachen University: Perth, Australia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Platsidou, M.; Daniilidou, A. Meaning in Life and Resilience among Teachers. J. Posit. Sch. Psychol. 2021, 5, 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Gully, S.M.; Eden, D. Validation of a New General Self-Efficacy Scale. Organ. Res. Methods 2001, 4, 62–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherbaum, C.A.; Cohen-Charash, Y.; Kern, M.J. Measuring General Self-Efficacy: A Comparison of Three Measures Using Item Response Theory. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2006, 66, 1047–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Pastore, S. Assessing Teachers’ Strategies in Formative Assessment: The Teacher Formative Assessment Practice Scale. J. Psychoeduc. Assess. 2022, 40, 592–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiliam, D.; Thompson, M. Integrating Assessment with Instruction: What Will It Take to Make It Work. In The Future of Assessment: Shaping Teaching and Learning; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; pp. 53–82. [Google Scholar]

- Civelek, M.E. Essentials of Structural Equation Modeling; Zea E-Books: Lincoln, Nebraska, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kock, N.; Hadaya, P. Minimum Sample Size Estimation in PLS-SEM: The Inverse Square Root and Gamma-exponential Methods. Inf. Syst. J. 2018, 28, 227–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling: Rigorous Applications, Better Results and Higher Acceptance. Long Range Plann. 2013, 46, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.; Alamer, A. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) in Second Language and Education Research: Guidelines Using an Applied Example. Res. Methods Appl. Linguist. 2022, 1, 100027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Sarstedt, M. Explanation Plus Prediction—The Logical Focus of Project Management Research. Proj. Manag. J. 2021, 52, 319–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansfield, C.F.; Beltman, S.; Price, A.; McConney, A. “Don’t Sweat the Small Stuff”: Understanding Teacher Resilience at the Chalkface. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2012, 28, 357–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, C.L.; Kuah, A.T.H.; Foong, R.; Ng, E.S. The Development of Emotional Intelligence, Self-efficacy, and Locus of Control in Master of Business Administration Students. Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 2020, 31, 113–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; King, R.B. Assessment Is Contagious: The Social Contagion of Formative Assessment Practices and Self-Efficacy among Teachers. Assess. Educ. 2023, 30, 130–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Pan, Z. Modeling the Effect of Chinese EFL Teachers’ Self-Efficacy and Resilience on Their Work Engagement: A Structural Equation Modeling Analysis. Sage Open 2023, 13, 21582440231214329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Gao, Y.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, P. Relationships between Self-Efficacy and Teachers’ Well-Being in Middle School English Teachers: The Mediating Role of Teaching Satisfaction and Resilience. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinberg, C. Assessment as An. Engl. Teach. Pract. Crit. 2008, 7, 42–64. [Google Scholar]

- Pfeiffer, S. The Vision of “Industrie 4.0” in the Making—A Case of Future Told, Tamed, and Traded. Nanoethics 2017, 11, 107–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godard, J. The Psychologisation of Employment Relations? Hum. Res. Manag. J. 2014, 24, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, R.A. The Education Leadership Challenges for Universities in a Postdigital Age. Postdigit Sci Educ 2024, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| PERFECTURE | 1/S | 2/S | 3/S | 4/S | 5/S | 6/S | 7/S | 8/S | 9/S | 10/S | 11/S | 12/S | 13/S | 14/S | 15/S | 16/S | 17/S | TOTAL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PIERIA | 1 | 7 | 6 | 3 | - | 20 | 3 | 4 | 1 | - | - | 16 | - | - | - | - | - | 61 |

| IMATHIA | - | 3 | 3 | 12 | 7 | 27 | 7 | 2 | 2 | 4 | - | 10 | - | - | - | - | - | 77 |

| PELLA | 9 | 14 | 9 | 12 | 8 | 31 | 6 | 1 | - | 1 | 3 | 5 | 1 | - | - | - | - | 100 |

| ΚΙLKIS | - | 5 | 6 | 3 | 1 | 12 | 2 | 2 | 3 | - | - | 7 | - | - | - | - | - | 41 |

| CHALKIDIKI | 3 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 4 | 17 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | - | 7 | - | - | - | - | - | 53 |

| A’ THESS/NIKI | 1 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 37 | 9 | 8 | 9 | 11 | 14 | 27 | 6 | 5 | 2 | 6 | 1 | 143 |

| Β’ THESS/NIKI | 2 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 46 | 10 | 8 | 10 | 14 | 22 | 37 | 9 | 1 | 1 | - | 1 | 176 |

| SERRES | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 45 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 7 | - | - | - | - | - | 78 |

| TOTAL | 729 | |||||||||||||||||

| CONSTRUCT | RETAINED OUTER LOADINGS AFTER DELETION |

|---|---|

| Emotional intelligence (EI) | 17, 20, 21, 24, 30 |

| Self—efficacy (SE) | 1, 2, 3, 4, 8 |

| Resilience (R) | 3, 4, 13, 16 |

| Formative Assessment (FA) | 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 10 |

| Cronbach’s Alpha | Composite Reliability (rho_a) | Composite Reliability (rho_c) | Average Variance Extracted (AVE) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EI | 0.769 | 0.773 | 0.844 | 0.519 |

| FA | 0.817 | 0.841 | 0.863 | 0.513 |

| R | 0.725 | 0.725 | 0.830 | 0.550 |

| SE | 0.783 | 0.794 | 0.851 | 0.534 |

| EMOTIONAL INTELLIGENCE | FORMATIVE ASSESSMENT | RESILIENCE | SELF-EFFICACY | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EI | 0.721 | |||

| FA | 0.273 | 0.716 | ||

| R | 0.569 | 0.462 | 0.741 | |

| SE | 0.492 | 0.214 | 0.541 | 0.731 |

| EMOTIONAL INTELLIGENCE | FORMATIVE ASSESSMENT | RESILIENCE | SELF-EFFICACY | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| assessment_1 | 0.216 | 0.773 | 0.458 | 0.301 |

| assessment_10 | 0.146 | 0.658 | 0.288 | 0.043 |

| assessment_2 | 0.098 | 0.713 | 0.262 | 0.161 |

| assessment_3 | 0.134 | 0.721 | 0.175 | 0.103 |

| assessment_4 | 0.305 | 0.727 | 0.410 | 0.157 |

| assessment_6 | 0.186 | 0.699 | 0.192 | 0.027 |

| efficacy_1 | 0.353 | 0.110 | 0.379 | 0.739 |

| efficacy_2 | 0.363 | 0.099 | 0.379 | 0.725 |

| efficacy_3 | 0.332 | 0.133 | 0.344 | 0.691 |

| efficacy_4 | 0.310 | 0.153 | 0.357 | 0.711 |

| efficacy_8 | 0.422 | 0.257 | 0.492 | 0.784 |

| emotional_17 | 0.690 | 0.201 | 0.391 | 0.353 |

| emotional_20 | 0.714 | 0.134 | 0.418 | 0.334 |

| emotional_21 | 0.734 | 0.194 | 0.347 | 0.284 |

| emotional_24 | 0.757 | 0.222 | 0.527 | 0.370 |

| emotional_30 | 0.707 | 0.227 | 0.340 | 0.417 |

| resilience_13 | 0.435 | 0.289 | 0.695 | 0.441 |

| resilience_16 | 0.429 | 0.324 | 0.720 | 0.414 |

| resilience_3 | 0.426 | 0.392 | 0.747 | 0.398 |

| resilience_4 | 0.393 | 0.357 | 0.799 | 0.346 |

| Heterotrait–Monotrait Ratio (HTMT) | |

|---|---|

| FA <-> EI | 0.493 |

| R <-> EI | 0.855 |

| R <-> FA | 0.678 |

| S <-> EI | 0.746 |

| SE <-> FA | 0.380 |

| SE <-> R | 0.828 |

| Original Sample (O) | Sample Mean (M) | Standard Deviation (STDEV) | T Statistics (|O/STDEV|) | p Values | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FA | 0.215 | 0.231 | 0.058 | 3.737 | 0.000 |

| R | 0.414 | 0.421 | 0.061 | 6.810 | 0.000 |

| SE | 0.242 | 0.252 | 0.049 | 4.972 | 0.000 |

| VIF | |

|---|---|

| EI -> FA | 1.592 |

| EI -> R | 1.319 |

| EI -> SE | 1.000 |

| R -> FA | 1.706 |

| SE -> FA | 1.521 |

| SE -> R | 1.319 |

| Direct | p | Indirect | p | Confidence Interval 97.5% | Total Direct | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EI -> SE -> FA | −0.029 | 0.445 | 0.047 | ||||

| EI -> SE -> R -> FA | 0.081 | 0.000 | 0.126 | ||||

| EI -> R -> FA | 0.190 | 0.001 | 0.307 | ||||

| EI -> SE -> R | 0.169 | 0.000 | 0.246 | ||||

| SE -> R-> FA | 0.164 | 0.000 | 0.247 | ||||

| EI -> FA | 0.032 | 0.680 | 0.273 | 0.001 | |||

| EI -> R | 0.400 | 0.000 | 0.569 | 0.000 | |||

| EI -> SE | 0.492 | 0.000 | 0.492 | 0.000 | |||

| R -> FA | 0.475 | 0.000 | 0.475 | 0.000 | |||

| SE -> FA | −0.059 | 0.424 | 0.106 | 0.000 | |||

| SE -> R | 0.344 | 0.000 | 0.344 | 0.000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Panagiotidou, A.; Chatzigeorgiou, C.; Christou, E.; Roussakis, I. Human Resource Management in Industry 4.0 Era: The Influence of Resilience and Self-Efficacy on the Relationship Between Emotional Intelligence and Formative Assessment: A Study of Public Primary Educational Organizations. Societies 2025, 15, 138. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15050138

Panagiotidou A, Chatzigeorgiou C, Christou E, Roussakis I. Human Resource Management in Industry 4.0 Era: The Influence of Resilience and Self-Efficacy on the Relationship Between Emotional Intelligence and Formative Assessment: A Study of Public Primary Educational Organizations. Societies. 2025; 15(5):138. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15050138

Chicago/Turabian StylePanagiotidou, Athanasia, Chryssoula Chatzigeorgiou, Evangelos Christou, and Ioannis Roussakis. 2025. "Human Resource Management in Industry 4.0 Era: The Influence of Resilience and Self-Efficacy on the Relationship Between Emotional Intelligence and Formative Assessment: A Study of Public Primary Educational Organizations" Societies 15, no. 5: 138. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15050138

APA StylePanagiotidou, A., Chatzigeorgiou, C., Christou, E., & Roussakis, I. (2025). Human Resource Management in Industry 4.0 Era: The Influence of Resilience and Self-Efficacy on the Relationship Between Emotional Intelligence and Formative Assessment: A Study of Public Primary Educational Organizations. Societies, 15(5), 138. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15050138