Resilient Rice Farming: Household Strategies for Coping with Recurrent Floods in Tempe Lake, Indonesia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

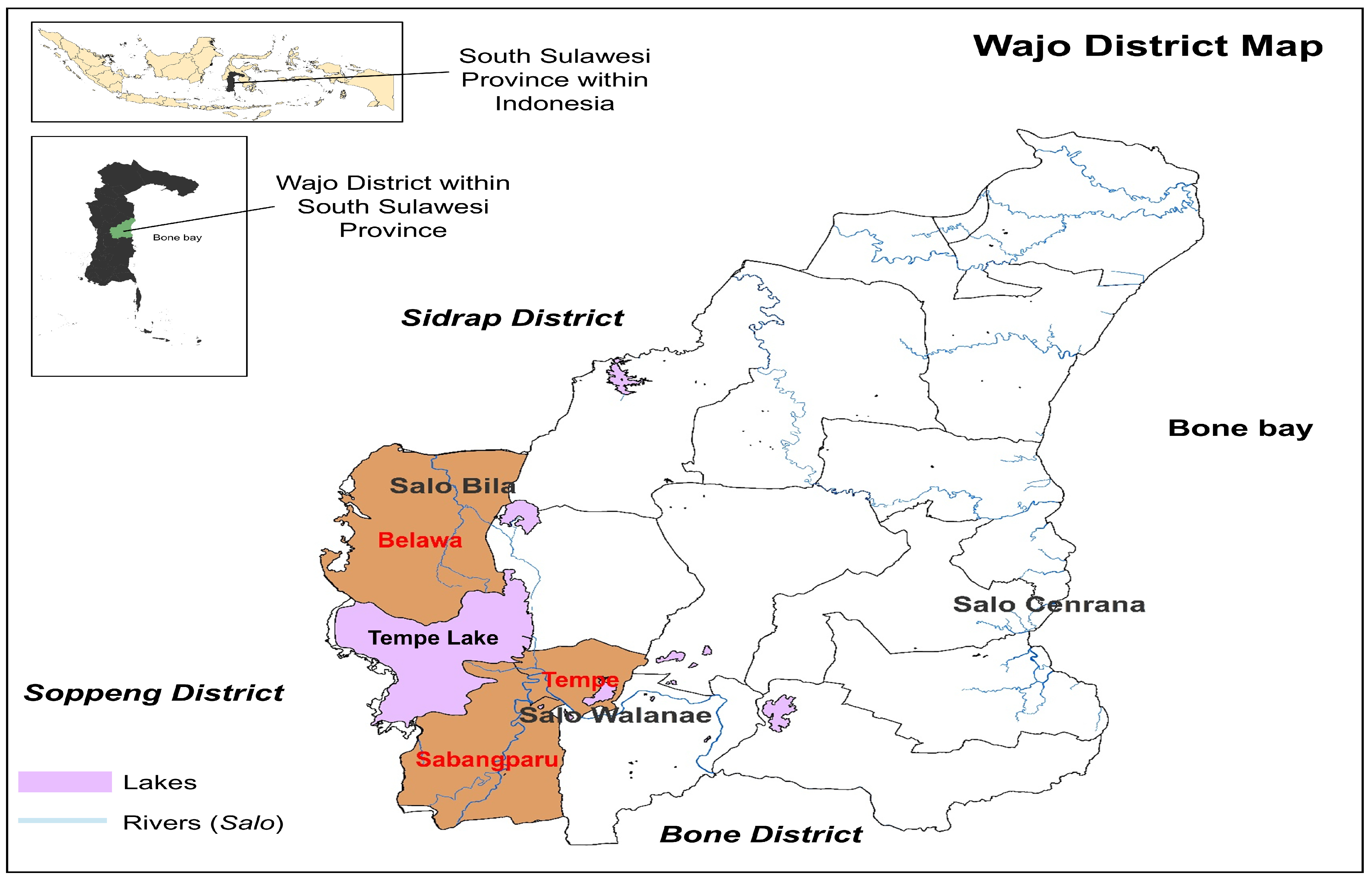

2.1. Study Sites

2.2. Study Design and Sampling

2.3. Data Collection

- (1)

- Household Survey: The study administered a structured questionnaire to all 160 households, capturing detailed socio-economic information, including household demographics, income sources, agricultural practices, and food security status;

- (2)

- Semi-Structured Interviews: In-depth interviews were conducted with ten key respondents (e.g., household heads and community leaders) to gain qualitative insights into adaptive strategies and coping mechanisms during floods. These interviews explored themes such as income diversification, social collaboration, and the use of flood-resistant crops;

- (3)

- Direct Observations: The study observed farming areas and households to document adaptive practices, such as planting schedules and flood mitigation techniques, and recorded field notes to contextualize survey and interview data.

2.4. Analytical Framework

3. Results

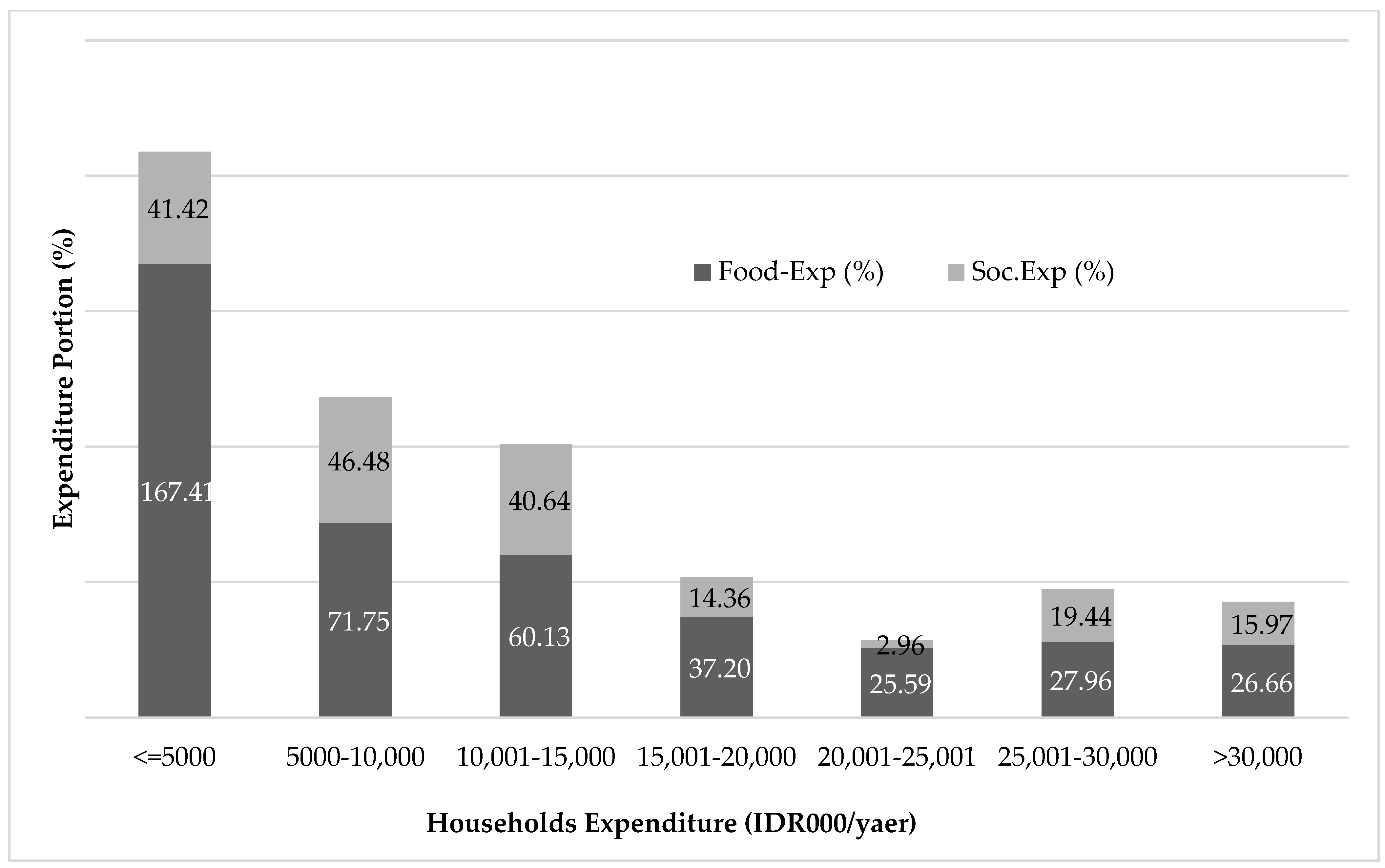

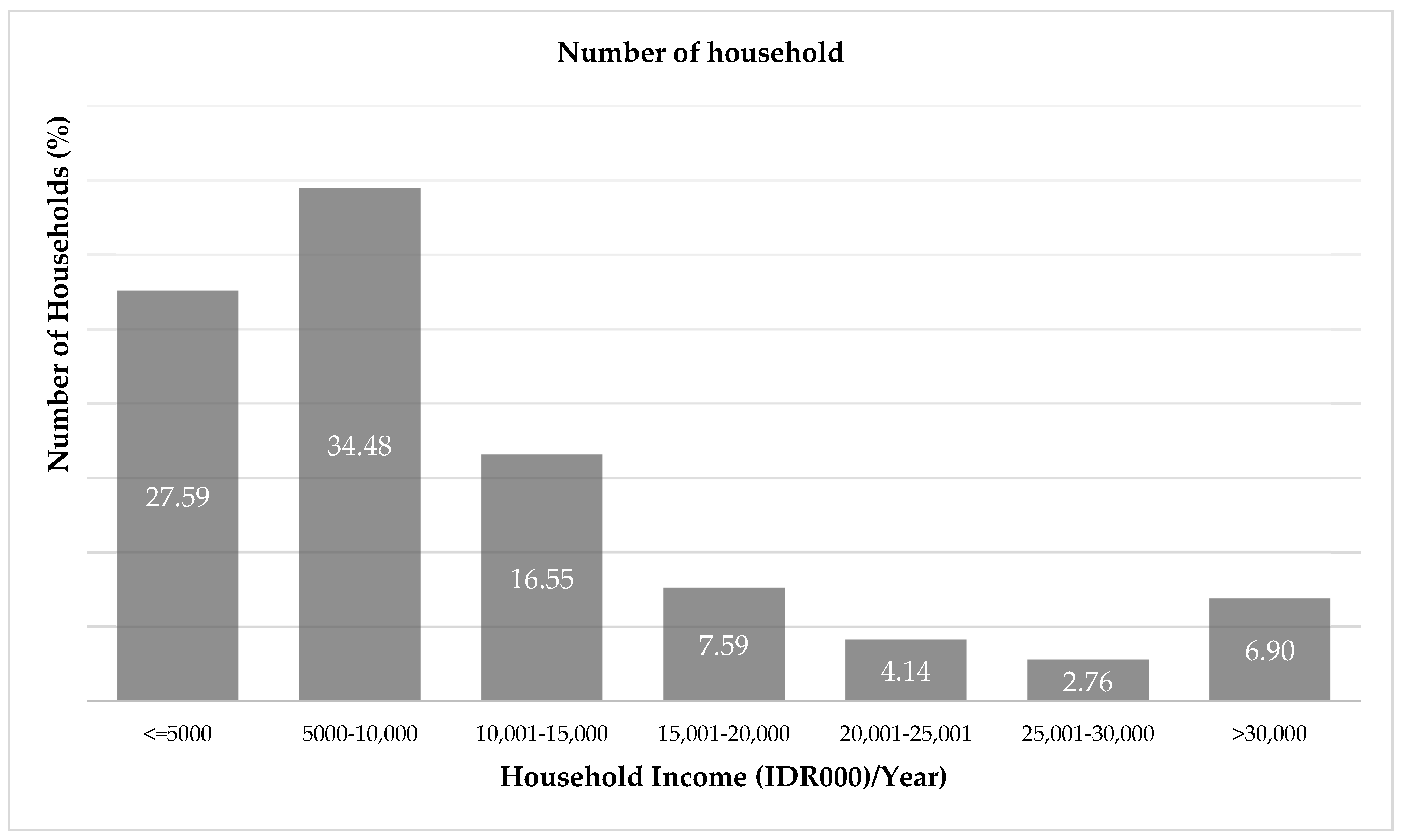

3.1. Household Socio-Economic Characteristics

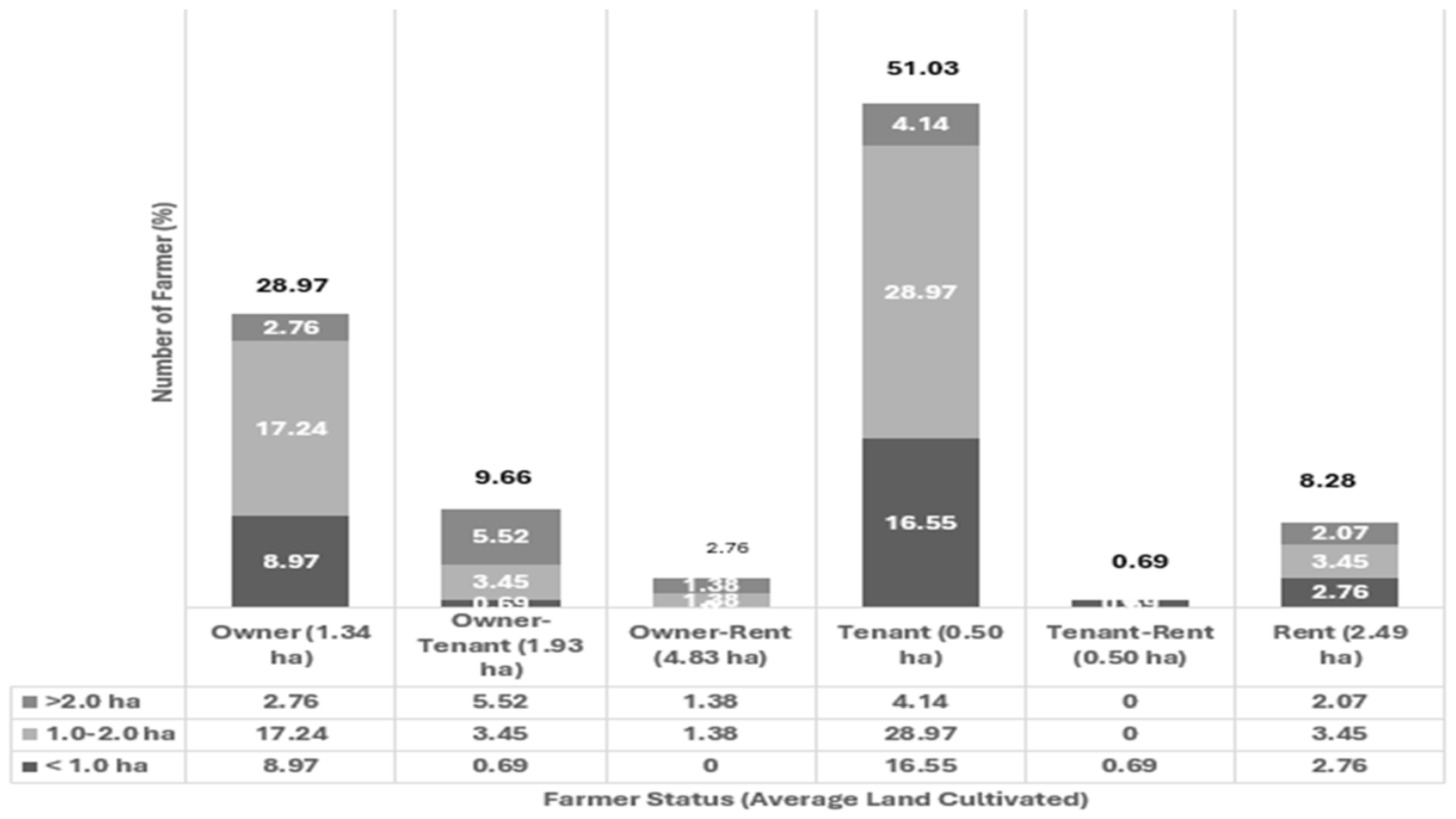

3.2. Farmer Status

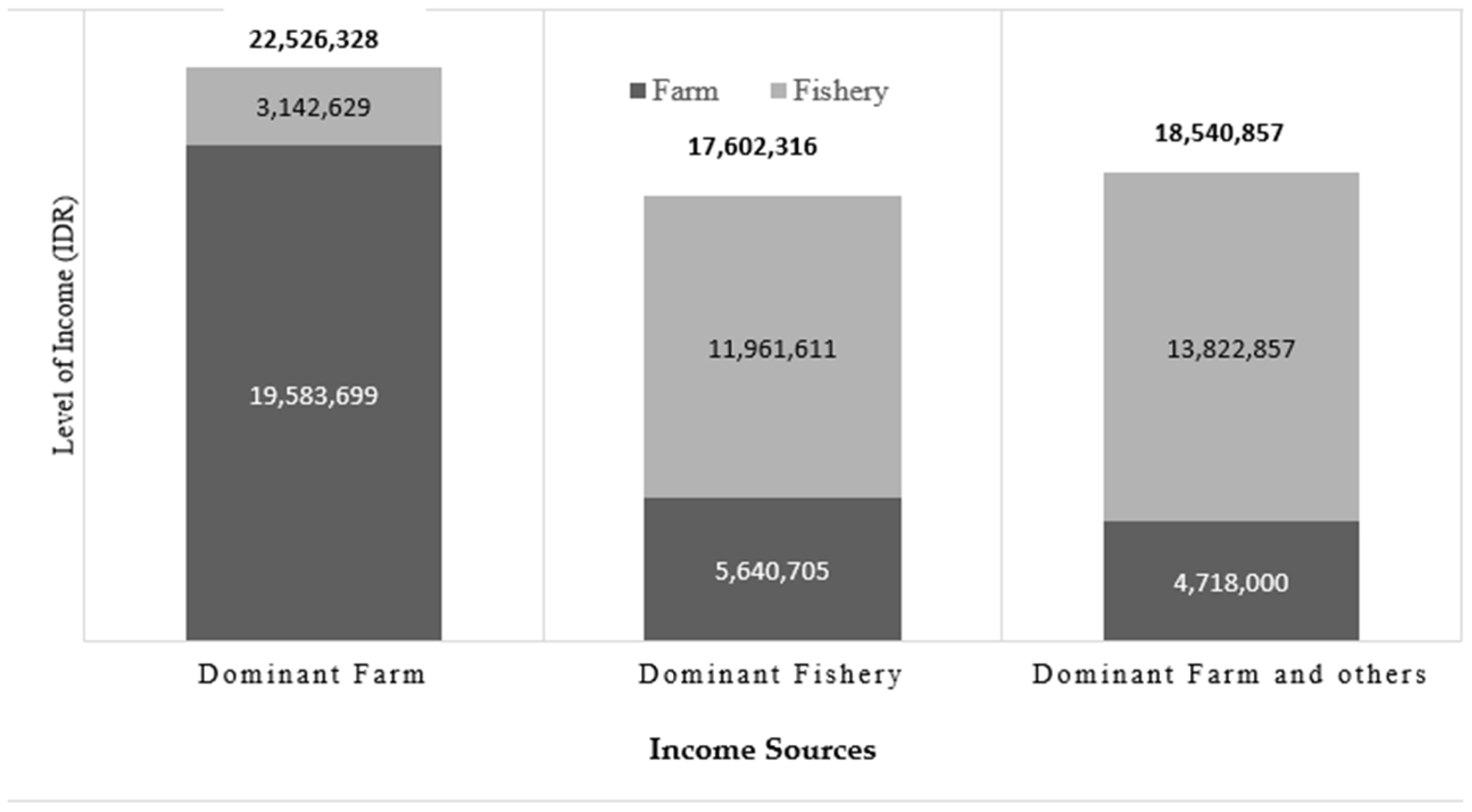

3.3. Livelihood Sources

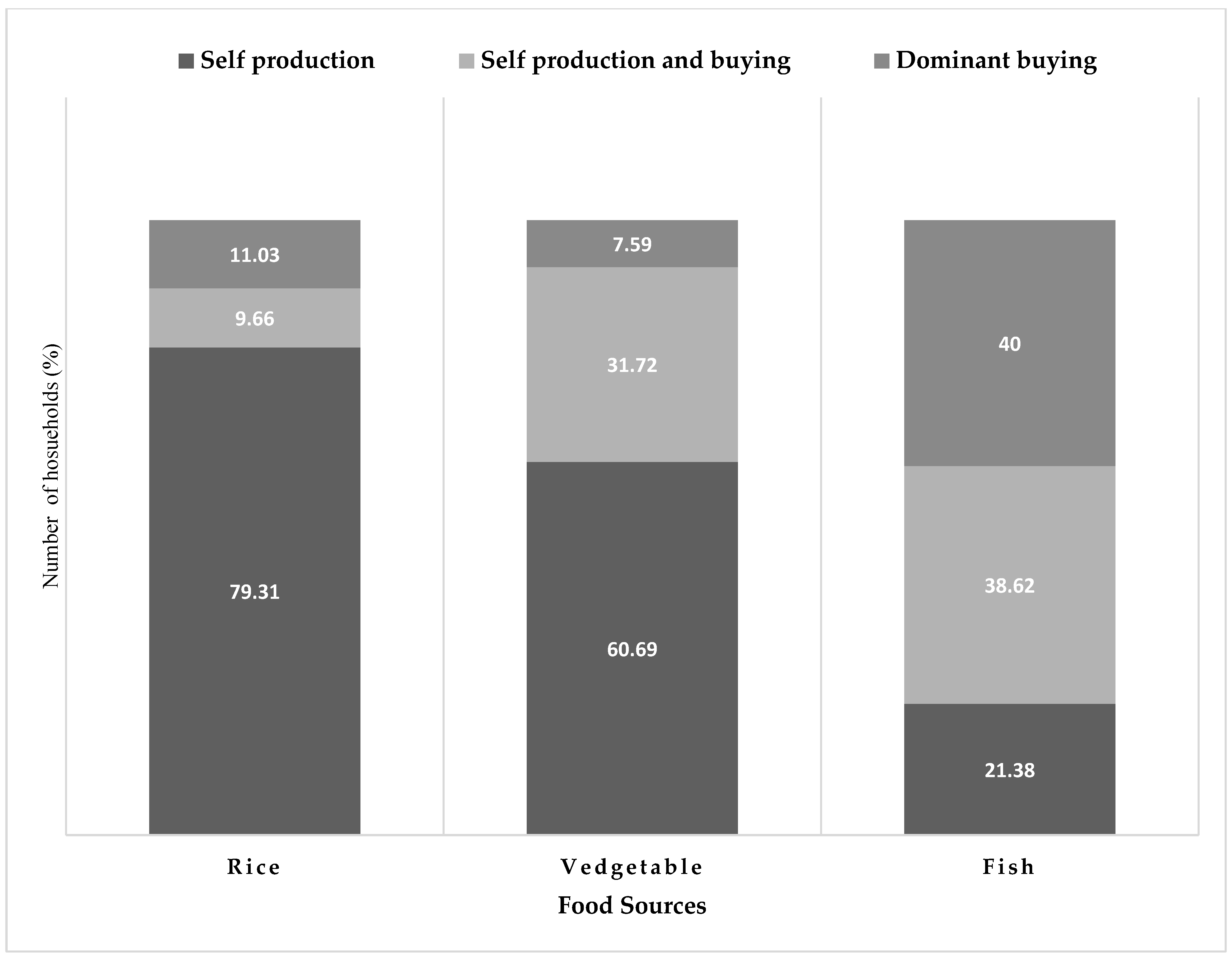

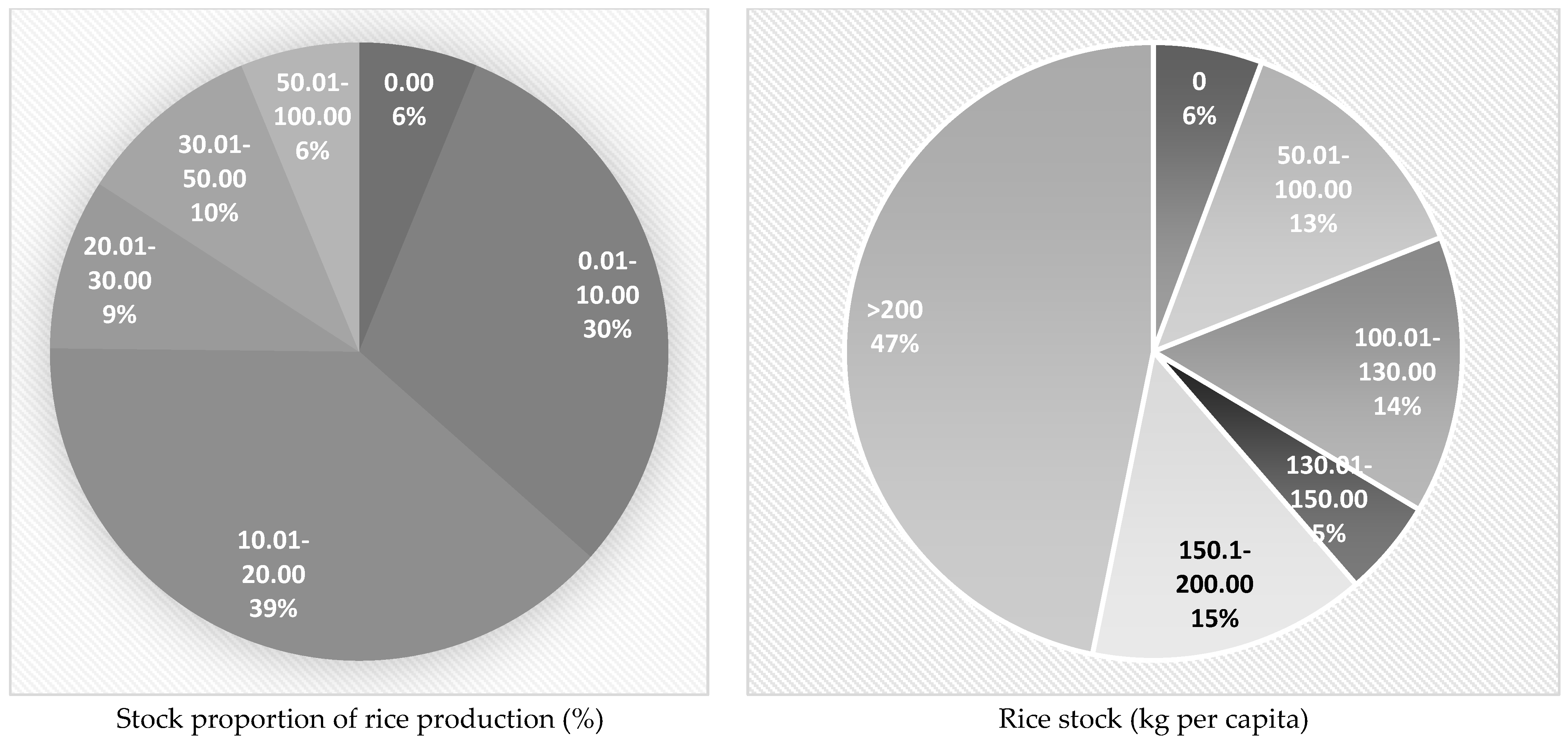

3.4. Food Sources and Consumption

4. Discussion

4.1. Farmer Households’ Adaptive Strategies for Flood Resilience

4.2. Food Fulfilment Strategy for Adapting to Flooding

4.3. Diversified Income Sources for Flood Adaptation Strategies

4.4. Strengthening Livelihoods and Enhancing Community Resilience

5. Conclusions and Policy Implications

Limitations of the Study

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dinh, Q.; Balica, S.; Popescu, I.; Jonoski, A. Climate change impact on flood hazard, vulnerability and risk of the Long Xuyen Quadrangle in the Mekong Delta. Int. J. River Basin Manag. 2012, 10, 103–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhassan, H. Farm households’ flood adaptation practices, resilience and food security in the Upper East region, Ghana. Heliyon 2020, 6, e04167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ntim-Amo, G.; Yin, Q.; Ankrah, E.K.; Liu, Y.; Ankrah Twumasi, M.; Agbenyo, W.; Xu, D.; Ansah, S.; Mazhar, R.; Gamboc, V.K. Farm households’ flood risk perception and adoption of flood disaster adaptation strategies in northern Ghana. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2022, 80, 103223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentle, P.; Maraseni, T.N. Climate change, poverty and livelihoods: Adaptation practices by rural mountain communities in Nepal. Environ. Sci. Policy 2012, 21, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darma, R.; Pada, A.A.T.; Bakri, R.; Darwis Amrullah, A.; Taufik, M. Community income analysis in lake Tempe Area, Wajo Regency. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 807, 032084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arouri, M.; Nguyen, C.; Youssef, A.B. Natural Disasters, Household Welfare, and Resilience: Evidence from Rural Vietnam. World Dev. 2015, 70, 59–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tambo, J.A. Adaptation and resilience to climate change and variability in north-east Ghana. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2016, 17, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awuor, O.L.; Edward, M.K. Harnessing the Potential of Underutilized Aquatic Bioresource for Food and Nutritional Security in Kenya. In Food Security and Safety: African Perspectives; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salam, M.; Sari, A.N.; Bakri, R.; Arsyad, M.; Saadah Jamil, M.H.; Tenriawaru, A.N.; Muslim, A.I. Determinant factors affecting farmers’ income of rice farming in Indonesia. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 343, 012115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akzar, R.; Amandaria, R. Climate change effects on agricultural productivity and its implication for food security. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 681, 012059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadiprayitno, I.I. Food security and human rights in Indonesia. Dev. Pract. 2010, 20, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neilson, J.; Wright, J. The state and food security discourses of Indonesia: Feeding the bangsa. Geogr. Res. 2017, 55, 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holling, C.S. Resilience and stability of ecological systems. In The Future of Nature: Documents of Global Change; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karsai, I.; Schmickl, T.; Kampis, G. Resilience and Stability of Ecological and Social Systems; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adger, W.N. Social and ecological resilience: Are they related? Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2000, 24, 347–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovett, J. Linking Social and Ecological Systems. Management Practices and Social Mechanisms for Building Resilience. In Environment and Development Economics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1999; Volume 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, R.; Conway, G.R. Sustainable rural livelihoods: Practical concepts for the 21st century. In IDS Discussion Paper 296; Institute of Development Studies: Brighton, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Dongdong, Y.; Xi, Y.; Weihong, S. How do ecological vulnerability and disaster shocks affect livelihood resilience building of farmers and herdsmen: An empirical study based on CNMASS data. Front. Environ. Sci 2022, 10, 998527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razafindrabe, B.H.N.; Parvin, G.A.; Surjan, A.; Takeuchi, Y.; Shaw, R. Climate Disaster Resilience: Focus on Coastal Urban Cities in Asia. Asian J. Environ. Disaster Manag. 2009, 1, 101–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassidy, L.; Barnes, G.D. Understanding household connectivity and resilience in marginal rural communities through social network analysis in the village of Habu, Botswana. Ecol. Soc. 2012, 17, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darma, R.; Connor, P.O.; Akzar, R.; Tenriawaru, A.N.; Amandaria, R. Enhancing Sustainability in Rice Farming: Institutional Responses to Floods and Droughts in Pump-Based Irrigation Systems in Wajo District, Indonesia. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dillen, S. Rural Livelihoods and Diversity in Developing Countries. J. Dev. Econ. 2003, 70, 248–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, F. Rural Livelihood Diversity in Developing Countries: Evidence and Policy Implications; Overseas Development Institute: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Dapilah, F.; Nielsen, J.Ø.; Friis, C. The role of social networks in building adaptive capacity and resilience to climate change: A case study from northern Ghana. Clim. Dev. 2020, 12, 42–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nhan, D.K.; Trung, N.H.; Van Sanh, N. The Impact of Weather Variability on Rice and Aquaculture Production in the Mekong Delta. In Advances in Global Change Research; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shikuku, K.M.; Winowiecki, L.; Twyman, J.; Eitzinger, A.; Perez, J.G.; Mwongera, C.; Läderach, P. Smallholder farmers’ attitudes and determinants of adaptation to climate risks in East Africa. Clim. Risk Manag. 2017, 16, 234–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gezie, M. Farmer’s response to climate change and variability in Ethiopia: A review. Cogent Food Agric. 2019, 5, 1613770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soekirman, A. Food and nutrition security and the economic crisis in Indonesia. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2001, 10, S57–S61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falcon, W.P.; Naylor, R.L.; Smith, W.L.; Burke, M.B.; McCullough, E.B. Using climate models to improve Indonesian food security. Bull. Indones Econ. Stud. 2004, 40, 355–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilby, R.L.; Keenan, R. Adapting to flood risk under climate change. Prog. Phys. Geogr. 2012, 36, 348–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, J.F.; Obidzinski, K. Framing the food poverty question: Policy choices and livelihood consequences in Indonesia. J. Rural Stud. 2017, 54, 344–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masud, M.M.; Azam, M.N.; Mohiuddin, M.; Banna, H.; Akhtar, R.; Alam, A.S.A.F.; Begum, H. Adaptation barriers and strategies towards climate change: Challenges in the agricultural sector. J. Clean Prod. 2017, 156, 698–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naing, N.; Santosa, H.R.; Soemarno, I. Kearifan Lokal Tradisional Masyarakat Nelayan Di Danau Tempe Sulawesi Selatan. Local Wisdom 2009, 1, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musdah, E.; Husein, R. Analisis Mitigasi Nonstruktural Bencana Banjir Luapan Danau Tempe. J. Gov. Public Policy 2014, 1, 648–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danianti, R.P.; Sarifuddin, S. Tingkat Kerentanan Masyarakat Terhadap Bencana Banjir Di Perumnas Tlogosari, Kota Semarang. J. Pengemb. Kota 2015, 3, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asti, A.F. Masyarakat Lokal Terhadap Banjir Tahunan Danau Tempe Di Kabupaten Wajo, Propinsi Sulawesi Selatan. In Proceedings of the Annual International Conference on Islamic Studies XIII, Surabaya, Indonesia, 5–8 November 2012; pp. 1429–1445. [Google Scholar]

- Naing, N.; Salim, H. Sistem Struktur Rumah Mengapung di Danau Tempe Sulawesi Selatan. J. Pemukim. 2013, 8, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusran Ali, M.S.S.; Dahliana, B.; Salman, D.; Dirpan, A.; Viantika, I.M. Community resilience in dealing with Tempe lake disaster. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 235, 012108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akzar, R.; Amiruddin, A.; Amandaria, R.; Rahmadanih Darma, R. Local foods development to achieve food security in Papua Province, Indonesia. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth. Environ Sci. 2020, 575, 012014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmer, P. Food Security in Indonesia: Current Challenges and the Long-Run Outlook. SSRN Electron. J. 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suryana, A. Menuju Ketahanan Pangan Indonesia Berkelanjutan 2025: Tantangan dan Penanganannya. Forum Penelit. Agro Ekon. 2014, 32, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diansari, P.; Nanseki, T. Perceived food security status—A case study of households in North Luwu, Indonesia. Nutr. Food Sci. 2015, 45, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saputri, R.; Lestari, L.A.; Susilo, J. Pola konsumsi pangan dan tingkat ketahanan pangan rumah tangga di Kabupaten Kampar Provinsi Riau. J. Gizi Klin. Indones. 2016, 12, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansar, M. Sustainable integrated farming system: A solution for national food security and sovereignty. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2018, 157, 012061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suciati, L.P.; Haryati, N.; Meitasari, D.; Zainuddin, A.; Murtisari, R.; Lasitya, D.S.; Irwandi, P.; Putri, R.W.; Aulia, B.M. Strategic Behavior of Small-Scale Farmers toward Sustainability of Rice Farming: A study of Entrepreneurial skill to Farming Performance. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2023, 1153, 012021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adebayo, E.F.; Dauna, Y.; Giroh, D.Y. Assessment Of Risk Factors In Rice Farming In Adamawa State, Nigeria. J. Agripreneurship Sustain. Dev. 2023, 6, 101–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwakyusa, L.; Dixit, S.; Herzog, M.; Heredia, M.C.; Madege, R.R.; Kilasi, N.L. Flood-tolerant rice for enhanced production and livelihood of smallholder farmers of Africa. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023, 7, 1244460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soeprobowati, T.R. Integrated Lake Basin Management for Save Indonesian Lake Movement. Procedia Environ. Sci. 2015, 23, 368–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salam, S.; Tantu, A.G.; Pallawagau, M. Penyelesaian Masalah Sosial Ekonomi Masyarakat KawasanDanau Tempe, Sulawesi Selatan. J. Penelit. Agrisamudra 2020, 7, 24–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.S.S.; Majika, A.; Salman, D. Food consumption and production in Tempe Lake, South Sulawesi, Indonesia. J. Asian Rural. Stud. 2017, 1, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zain, M.M. Overcoming the Deluge: The Community Resilience in Temp Lake, Indonesia. Pak. J. Life Soc. Sci. 2022, 20, 252–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humanitarian Data Exchange. Indonesia. Subnational Administrative Boundaries 2020. Available online: https://data.humdata.org/dataset/cod-ab-idn (accessed on 21 December 2024).

- Lapak, G.I.S. Shapefile Sulawesi Selatan. Lapak GISCom 2020. Available online: https://www.lapakgis.com/2020/07/shapefile-provinsi-sulawesi-selatan.html (accessed on 21 December 2024).

- De Bruijn, K.M. Resilience and flood risk management. Water Policy 2004, 6, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vadeboncoeur, Y.; Peterson, G.; Zanden, J.V.; Kalff, J. Benthic algal production across lake size Gradients: Interactions among morphometry, nutrients, and light. Ecology 2008, 89, 2542–2552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seneviratne, S.I.; Nicholls, N.; Easterling, D.; Goodess, C.M.; Kanae, S.; Kossin, J.; Luo, Y.; Marengo, J.; McInnes, K.; Rahimi, M.; et al. Changes in climate extremes and their impacts on the natural physical environment. In Managing the Risks of Extreme Events and Disasters to Advance Climate Change Adaptation: Special Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, I.; Hwang, Y.H.; Joo, S.T. Meat analog as future food: A review. J. Anim. Sci. Technol. 2020, 62, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bin Rahman, A.N.M.R.; Zhang, J. Flood and drought tolerance in rice: Opposite but may coexist. Food Energy Secur. 2016, 5, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, K.; Nelson, J. Sustainable Livelihoods and Livelihood Diversification; IDS Working Paper; Institute of Development Studies: Brighton, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- van den Berg, M. Household income strategies and natural disasters: Dynamic livelihoods in rural Nicaragua. Ecol. Econ. 2010, 69, 592–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakakaawa, C.; Moll, R.; Vedeld, P.; Sjaastad, E.; Cavanagh, J. Collaborative resource management and rural livelihoods around protected areas: A case study of Mount Elgon National Park, Uganda. For. Policy Econ. 2015, 57, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leinbach, T.R. Small enterprises, fungibility and Indonesian rural family livelihood strategies. Asia Pac. Viewp. 2003, 44, 7–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antara, M.; Lamusa, A.; Effendy Laksmayani, M.K.; Tangkesalu, D.; Imran, E. Income Diversity and Other Socioeconomic Factors That Influence the Household Food Security of Small-Scale Lowland Rice Farmers in Indonesia. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. Plan. 2023, 18, 971–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purwaningsih, Y.; Daerobi, A.; Mulyaningsih, T. Farmer’s Adaptation to Climate Change as Strategy to Achieve Food Security. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2022, 985, 012001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael, P.S.; Mwakyusa, L.; Sanga, H.G.; Shitindi, M.J.; Kwaslema, D.R.; Herzog, M.; Meliyo, J.L.; Massawe, B.H. Floods stress in lowland rice production: Experiences of rice farmers in Kilombero and Lower-Rufiji floodplains, Tanzania. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023, 7, 1206754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baishakhy, S.D.; Islam, M.A.; Kamruzzaman, M. Overcoming barriers to adapt rice farming to recurring flash floods in haor wetlands of Bangladesh. Heliyon 2023, 9, e14011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amandaria, R.; Darma, R.; Zain, M.M.; Fudjaja, L.; Wahda, M.A.; Kamarulzaman, N.H.; Bakheet Ali, H.; Akzar, R. Sustainable Resilience in Flood-Prone Rice Farming: Adaptive Strategies and Risk-Sharing Around Tempe Lake, Indonesia. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eakin, H.; Appendini, K. Livelihood change, farming, and managing flood risk in the Lerma Valley, Mexico. Agric. Hum. Values 2008, 25, 555–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keim, M.E. Floods. Koenig and schultz’s Disaster Medicine. In Comprehensive Principles and Practices; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McElwee, P.; Nghiem, T.; Le, H.; Vu, H. Flood vulnerability among rural households in the Red River Delta of Vietnam: Implications for future climate change risk and adaptation. Nat. Hazards 2017, 86, 465–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhraief, M.Z.; Dhehibi, B.; Daly Hassen, H.; Zlaoui, M.; Khatoui, C.; Jemni, S.; Jebali, O.; Rekik, M. Livelihoods Strategies and Household Resilience to Food Insecurity: A Case Study from Rural Tunisia. Sustainability 2019, 11, 907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caramanica, A. Building resilience from risk: Interactions across ENSO, local environment, and farming systems on the desert north coast of Peru (1100BC–AD1460). Holocene 2022, 32, 1410–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulaiman, A.; Saleh Ali, M.S.; Saud, Y.M.; Rahmadanih. Power and Interest of Actors in Using Tempe Lake in South Sulawesi. Hong Kong J. Soc. Sci. 2022, 59, 416–426. [Google Scholar]

- Mayes, S.; Massawe, F.J.; Alderson, P.G.; Roberts, J.A.; Azam-Ali, S.N.; Hermann, M. The potential for underutilized crops to improve security of food production. J. Exp. Bot 2012, 63, 1075–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamka, I.M.; Naping, H. Nelayan Danau Tempe: Strategi Adaptasi Masyarakat dalam Menghadapi Kondisi Perubahan Musim. ETNOSIA J. Etnogr. Indones. 2019, 4, 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, P.; Defries, R.; Clark, J.; Flowerhill, N.; Arif, M.; Harou, A.; Downs, S.; Fanzo, J. Multiple cropping alone does not improve year-round food security among smallholders in rural India. Environ. Res. Lett. 2021, 16, 065017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, C.; Dimitrova Mårtensson, L.M.; Zachrison, M.; Carlsson, G. Sustainability of Diversified Organic Cropping Systems—Challenges Identified by Farmer Interviews and Multi-Criteria Assessments. Front. Agron. 2021, 3, 698968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anang, B.T.; Bäckman, S.; Sipiläinen, T. Agricultural microcredit and technical efficiency: The case of smallholder rice farmers in Northern Ghana. J. Agric. Rural. Dev. Trop. Subtrop. 2016, 117, 189–202. [Google Scholar]

- Robert, F.C.; Frey, L.M.; Sisodia, G.S. Village development framework through self-help-group entrepreneurship, microcredit, and anchor customers in solar microgrids for cooperative sustainable rural societies. J. Rural Stud. 2021, 88, 432–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran, M.; Ul Haq, S.; Ozcatalbas, O. Role of Microcredit in Sustainable Rural Development. In Sustainable Rural Development Perspective and Global Challenges; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudsiah, H.; Suwarni Rahim, S.W.; Hidayani, A.A.; Moka, W. Population dynamic of bungo fish (Glossogobius giuris) in three integrated lakes (Danau Tempe, Danau Sidenreng, and Danau Lampokka) South Sulawesi during rainy season. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 777, 012010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegmon, M. The Risks of Sharing and Sharing as Risk Reduction: Interhousehold Food Sharing in Egalitarian Societies. Between Bands States 1991, 9, 309–329. [Google Scholar]

- Kantun, W.; Fatma, W.M.; Rapi, N.L.; Awaluddin. Bioaccumulation of heavy metals in Bungo Fish (Glossogobius giuris Hamilton, 1822) in Lake Tempe, South Sulawesi, Indonesia. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2024, 1410, 012048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Zhang, C.; Song, J.; Qiu, Z.; Li, W.; Wang, W. Do Livelihood Strategies Affect the Livelihood Resilience of Farm Households in Flooded Areas? Evidence From Hubei Province, China. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2022, 10, 909172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Range (N = 160) | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year) | <40 | 40–60 | >60 | |

| 29.66 | 60.00 | 10.34 | 100.00 | |

| Employment | Farmer | Farmer+fihserment | Farmer+others | |

| 2.07 | 84.83 | 13.10 | 100.00 | |

| Household head education | Illiterate | Elementary | High school | |

| 20.69 | 54.48 | 24.82 | 100.00 | |

| Household size (people) | <4 | 4–6 | >6 | |

| 58.62 | 37.24 | 4.4 | 100 | |

| History settlement in the lake region | Place of birth | Marriage with a local resident | Migration to the lake region | |

| 57.24 | 29.66 | 13.10 | 100.00 | |

| Income Sources | Frequency (n = 160) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variation (%) | Lowest | Highest | Respondent (%) | |

| Dominant Farm | 74.92 | 1,540,000 | 81,036,000 | 61.38 |

| Farm | 78.08 | 810,000 | 55,472,000 | |

| Fishing | 140.36 | 120,000 | 5,560,000 | |

| Dominant Fishing | 68.86 | 1,979,000 | 45,707,520 | 24.83 |

| Farm | 97.37 | 240,000 | 21,876,000 | |

| Fishing | 73.49 | 1,200,000 | 33,900,000 | |

| Farm-Fishery-Others | 92.16 | 1,212,600 | 85,060,000 | 13.79 |

| Farm | 69.38 | 732,600 | 75,460,000 | |

| Fishing | 86.28 | 300,000 | 23,580,000 | |

| Total Income | 27.96 | 4,015,200 | 85,060,200 | 100.00 |

| Farm | 6.00 | 720,400 | 75,460,000 | |

| Fishing | 112.42 | 240,000 | 33,900,000 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Darma, R.; Rahmadanih, R.; Zain, M.M.; Amandaria, R.; Mario, M.; Akzar, R. Resilient Rice Farming: Household Strategies for Coping with Recurrent Floods in Tempe Lake, Indonesia. Societies 2025, 15, 129. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15050129

Darma R, Rahmadanih R, Zain MM, Amandaria R, Mario M, Akzar R. Resilient Rice Farming: Household Strategies for Coping with Recurrent Floods in Tempe Lake, Indonesia. Societies. 2025; 15(5):129. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15050129

Chicago/Turabian StyleDarma, Rahim, Rahmadanih Rahmadanih, Majdah M. Zain, Riri Amandaria, Mario Mario, and Rida Akzar. 2025. "Resilient Rice Farming: Household Strategies for Coping with Recurrent Floods in Tempe Lake, Indonesia" Societies 15, no. 5: 129. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15050129

APA StyleDarma, R., Rahmadanih, R., Zain, M. M., Amandaria, R., Mario, M., & Akzar, R. (2025). Resilient Rice Farming: Household Strategies for Coping with Recurrent Floods in Tempe Lake, Indonesia. Societies, 15(5), 129. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15050129