Beyond Accessibility Compliance: Exploring the Role of Information on Apparel Shopping Websites for the Blind and Visually Impaired

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Blindness Spectrum and Challenges for Independence

1.2. Digital Accessibility

1.3. Theoretical Framework

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Qualitative Inquiry

2.2. Data Collection and Analysis

3. Results

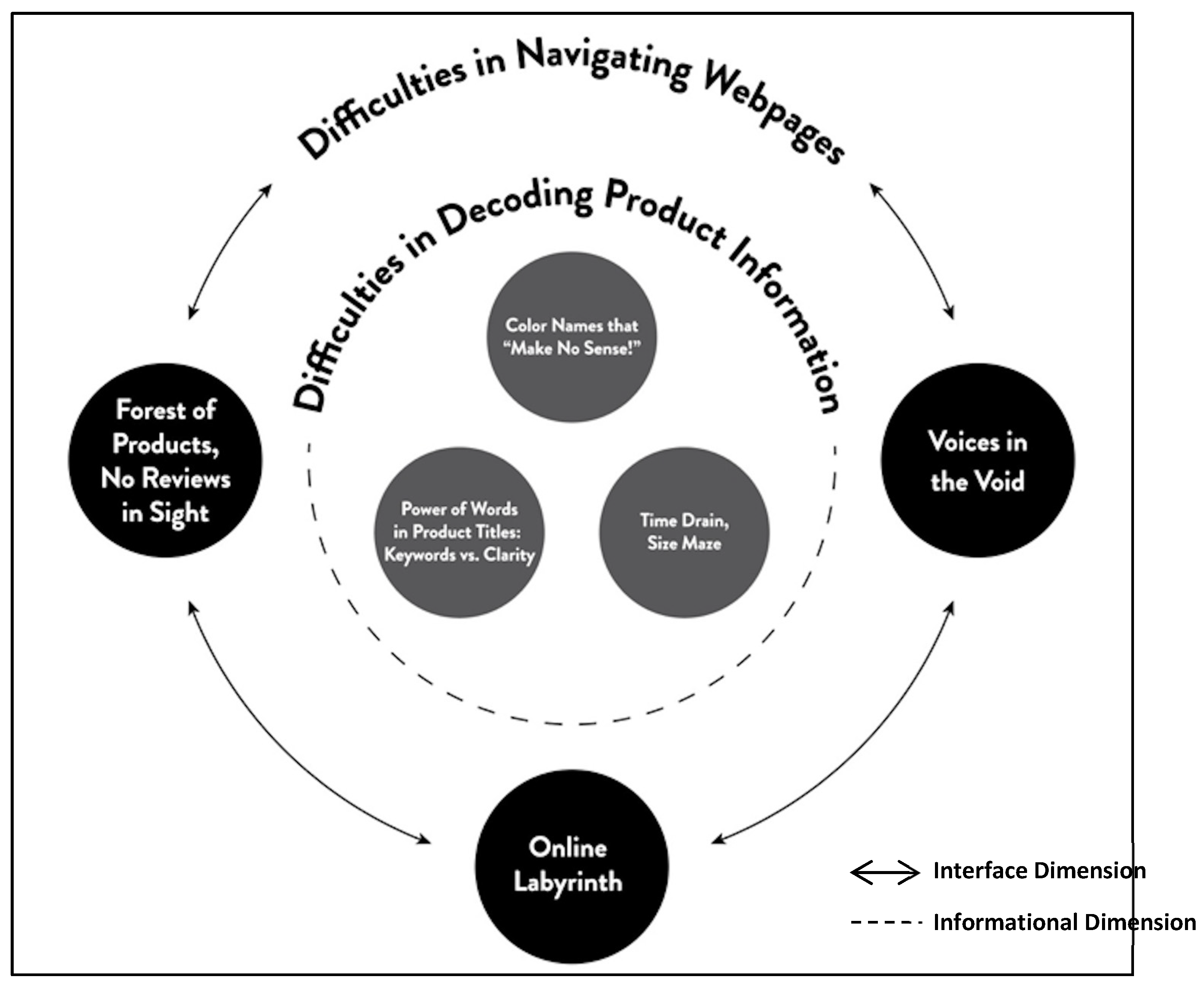

3.1. Difficulties in Decoding Product Information (Culnan’s [11] Informational Dimension)

3.1.1. Color Names That “Make No Sense.”

Dani: “Camo multi-3 [which is exactly ready by JAWS®]. So it should have 3 colors [in my mind], but I can only see black and maybe a gray? I was assuming by the name, that it was shades of green and tan…Isn’t that what you think when you think camo? (…) It’s hard for me to differentiate but usually those [green and tan] are lighter shades [than black and gray] with my vision and these look almost black”.

3.1.2. Power of Words in Product Titles: Keywords vs. Clarity

3.1.3. Time Drain, Size Maze

3.2. Difficulties in Navigating Webpages (Culnan’s [11] Interface Dimension)

3.2.1. Online Labyrinth

“I find shopping online to be rather frustrating, either in the case of websites not being accessible with JAWS® or having so many links, advertisements, and stuff like that [visual stimulated shopping pathways]. Sometimes it’s hard to navigate around and just ‘quote, unquote’ see what’s on the screen”.

3.2.2. Forest of Products, No Reviews in Sight

3.2.3. Voices in the Void

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chevalier, Stephanie: Leading Fashion E-Commerce Companies Worldwide. 2023. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/245648/leading-fashion-e-commerce-companies-by-market-cap/ (accessed on 6 March 2025).

- Andreas Kleynhans, S.; Fourie, I. Ensuring accessibility of electronic information resources for visually impaired people: The need to clarify concepts such as visually impaired. Library Hi Tech 2014, 32, 368–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Technology-Related Assistance for Individuals with Disabilities Act of 1988, 29 U.S.C. § 2201 et seq. 1988. Available online: https://www.congress.gov/bill/100th-congress/senate-bill/2561 (accessed on 26 March 2025).

- United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. Available online: https://www.un.org/disabilities/documents/convention/convention_accessible_pdf.pdf (accessed on 6 March 2025).

- The World Health Organization. International Classification of Diseases (ICD 10). Available online: https://icd.who.int/browse10/2019/en#/H54 (accessed on 20 June 2024).

- Bashiti, A.; Rahim, A.A. Physical barriers faced by people with disabilities (pwds) in shopping malls. Procedia—Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 222, 414–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazar, J.; Goldstein, D.; Taylor, A. Ensuring Digital Accessibility Through Process and Policy; Morgan Kauffman: Burlington, MA, USA, 2015; ISBN 9780128006467. [Google Scholar]

- W3C. Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) 2.1. Available online: https://www.w3.org/TR/WCAG21/#background-on-wcag-2 (accessed on 7 May 2024).

- United States Department of Justice. Guidance on Web Accessibility and the ADA. Available online: www.ADA.gov (accessed on 2 March 2024).

- United Nations Sustainable Development Group. Disability Inclusion Practice Note Working Draft: ICT & Digital Accessibility. Available online: https://unsdg.un.org/sites/default/files/2021-04/ICT-Digital%20Accessbility-BOS-Disability%20Inclusion-Practice%20Note-20210303.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2024).

- Culnan, M. The dimensions of perceived accessibility to information: Implications for the delivery of information systems and services. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. 1985, 36, 302–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleck, H. What Blindness Really Looks Like. Available online: https://www.perkins.org/what-blindness-really-looks-like/ (accessed on 20 June 2024).

- World Health Organization (WHO). Vision Impairment and Blindness. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/blindness-and-visual-impairment (accessed on 14 July 2024).

- Barbosa, N.M.; Hayes, J.; Kaushik, S.; Wang, Y. Every website is a puzzle!: Facilitating access to common website features for people with visual impairments. Trans. Access. Comput. (TACCESS) 2022, 15, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leporini, B.; Paternò, F. Applying web usability criteria for vision-impaired users: Does it really improve task performance? Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2008, 24, 17–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Kim, J.; Jung, H. Challenges and design opportunities for easy, economical, and accessible offline shoppers with visual impairments. In Proceedings of the 2020 Symposium on Emerging Research from Asia and on Asian Contexts and Cultures, Honolulu, HI, USA, 25 April 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zor, B.S.; Vuruskan, A. Developing an assistive technology for individuals with visual impairment: Smart glove concept. In Proceedings of the 2022 AUTEX 21st World Textile Conference on Passion for Innovation, Lodz, Poland, 10 June 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira, J.; Cunha, J.; do Amaral, I. The Problems of a Visually Impaired User in the Process of Buying Fashion Products. In Proceedings of the International Fashion and Design Congress, Mexico City, Mexico, 4–6 October 2023; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabel, A.; McBee-Black, K.; Dimka, J. Apparel-related participation barriers: Ability, adaptation, engagement. Disabil. Rehabil. 2016, 38, 2184–2192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramalta, A.; Mastamet-Mason, A. The decision-making processes of visually impaired consumers in an apparel retail environment. In Proceedings of the 2013 Design Education Forum of Southern Africa Conference Design Cultures: Encultured Design, Vanderbijlpark, South Africa, 2–3 September 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Stangl, A.; Kothari, E.; Jain, S.; Yeh, T.; Grauman, K.; Gurari, D. BrowseWithMe: An online clothes shopping assistant for people with visual impairments. In Proceedings of the 20th International ACM SIGACCESS Conference on Computers and Accessibility, Galway, Ireland, 22 October 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosma Navigating Blindness. Available online: https://www.bosma.org/ (accessed on 15 May 2024).

- Lee, S.; Reddie, M.; Carroll, J.M. Designing for independence for people with visual impairments. In Proceedings of the Association for Computing Machinery Human-Computer Interaction, Yokohama, Japan, 8–13 May 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M. Mobile App Design Research Project: Blind People to Enjoy an Independent Clothing Lifestyle. Unpublished. Master’s Thesis, Ewha Woman’s University, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Alluqmani, A.; Harvey, M.; Zhang, Z. The barriers to online clothing websites for visually impaired people: An interview and observation approach to understanding needs. In Proceedings of the Designing Interactive Systems Conference, Pittsburg, PA, USA, 10–14 July 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J.B. The Online Apparel Shopping Experience of Blind Consumers. Unpublished. Ph.D. Dissertation, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Botelho, F.H. Accessibility to digital technology: Virtual barriers, real opportunities. Assist. Technol. 2021, 33, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Gordón, M.-L.; Moreno, L. Toward an integration of web accessibility into testing processes. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2014, 27, 281–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Grieves, J.; Kaneko, M. Engineering Software for Accessibility; Microsoft Press: Redmond, WA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bhowmick, A.; Hazarika, S. An insight into assistive technology for the visually impaired and blind people: State-of-the-art and future needs. J. Multimodal User Interfaces 2017, 11, 149–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freedom Scientific. Available online: https://www.freedomscientific.com/products/software/jaws/ (accessed on 20 June 2024).

- Djamasbi, S.; Tullis, T.; Girouard, M.; Hebner, M.; Krol, J.; Terranova, M. Web accessibility for visually impaired users: Extending the technology acceptance model (TAM). In Proceedings of the Americas Conference on Information Systems, Acapulco, Mexico, 6 August 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Merriam, S.B.; Tisdell, E.J. Qualitative Research: A Guide to Design and Implementation, 4th ed.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2015; ISBN 9781394266449. [Google Scholar]

- Moustakas, C. Phenomenological Research Methods; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Akhtar, W.H.; Watanabe, C.; Tou, Y.; Neittaanmäki, P. A new perspective on the textile and apparel industry in the digital transformation era. Textiles 2022, 2, 633–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha-Brookshire, J.E.; Dyer, B. Apparel import intermediaries: The impact of a hyperdynamic environment on u.s. apparel firms. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2008, 26, 339–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiggle, S. Analysis and interpretation of qualitative data in consumer research. J. Consum. Res. 1994, 21, 491–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jameson, K.A.; Alvarado, N. The relational correspondence between category exemplars and names. Philos. Psychol. 2003, 16, 25–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dimensions | Perceived Accessibility to Information 1 | Digital Accessibility Adaptation 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Physical | Gaining physical access to a terminal and system. | Gaining physical access to a personal computer and an apparel website through assistive technology. |

| Interface | The extent of translating a request into a non-natural language. | The use of assistive technology features to command the language to formulate a website query and navigate between webpages. |

| Informational | The ability to retrieve the information independent of any subsequent judgment as to the item’s relevance. | The use of assistive technology to retrieve desired information based upon command language of website query and subsequent judgment to the output’s relevance. |

| Participant 1 | Age | Vision 2 and Perception Level 3 | Online Shopping Frequency | Assistive Technology | Assistive Technology Experience Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dani | 53 | Blind, SLP | Often | Magnifier, colored keyboard, reading lamp | Knowledgeable |

| Eva | 42 | Blind, NLP | Often | JAWS®, braille keyboard | Expert |

| Suzy | 50 | Low vision, SLP | Often | Zoom text, magnifier | Learning |

| Nora | 51 | Blind, SLP | Often | JAWS®, Zoom text, magnifier | Knowledgeable |

| Piper | 69 | Low vision, SLP | New | Zoom text, magnifier | Learning |

| Rita | 39 | Blind, SLP | Often | JAWS® | Knowledgeable |

| Mia | 32 | Blind, SLP | Often | Fusion | Knowledgeable |

| Kate | 28 | Blind, SLP | Often | JAWS® | Expert |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nicoson, E.; Ha-Brookshire, J. Beyond Accessibility Compliance: Exploring the Role of Information on Apparel Shopping Websites for the Blind and Visually Impaired. Societies 2025, 15, 90. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15040090

Nicoson E, Ha-Brookshire J. Beyond Accessibility Compliance: Exploring the Role of Information on Apparel Shopping Websites for the Blind and Visually Impaired. Societies. 2025; 15(4):90. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15040090

Chicago/Turabian StyleNicoson, Emma, and Jung Ha-Brookshire. 2025. "Beyond Accessibility Compliance: Exploring the Role of Information on Apparel Shopping Websites for the Blind and Visually Impaired" Societies 15, no. 4: 90. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15040090

APA StyleNicoson, E., & Ha-Brookshire, J. (2025). Beyond Accessibility Compliance: Exploring the Role of Information on Apparel Shopping Websites for the Blind and Visually Impaired. Societies, 15(4), 90. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15040090