3. Applications of the Paradigms on Employment Relations

For each of the different sociological perspectives, applications are given in this section from the representativeness criteria in the European Commission Decision 500 of 1998 [

8], from the methodology of Eurofound representativeness studies, or from specificities of sectors, for which such representativeness studies have been conducted.

The interpretative sociological theory of Max Weber looks for meaning that actors give through their subjective experience of social realities. Equal importance is given to the expectations, concerns, and beliefs of the actors as well as to their behavior, which is more than the direct observable facts, to which positivists like Emile Durkheim limit their observations. To understand the real meaning of representativeness in each of the 27 EU member states, a combined quantitative approach and a qualitative empathic approach is needed to grasp the situation in its own interpretation, which applies to all three of the representativeness criteria in Article 1 of European Commission Decision 500 of 1998. These three criteria for national member organisations are the following:

- (a)

The national member organisations shall relate to specific sectors or categories and be organised at the European level;

- (b)

They shall consist of organisations which are themselves an integral and recognized part of Member States’ social partner structures and have the capacity to negotiate agreements, and which are representative of several Member States;

- (c)

They shall have adequate structures to ensure their effective participation in the work of the Committees.

The first criterium for representativeness is about the sector relatedness, how the membership domain of national sectoral trade unions and employers’ organisations matches partly or completely the entire scope of a sector. An example of how interpretative sociology helps to better understand the sectors comes with the sea fisheries sector, which is not part of the food producing sector, but because of the specificities of the work of seafarers, and the fact that they are represented by (maritime) transport trade unions, it is closer linked to the transport sectors. A good understanding of the different parts within a sector also helps to better understand the entire sector. For example, the construction sector covers large public works, like bridges, tunnels, or roads, but also an entire house that is being build, or special construction sector crafts, like electricity works, painting, or flooring. The chemical sector for example covers basic chemicals, specialty chemicals (like for example glue, paint, cleaning products, etc.), pharmaceuticals, rubber, and plastics.

The second representativeness criterium in the European Commission Decision 500 of 1998 mentions that national social partner organisations need to be recognized as an integral part of the social partner structures of the country. This cannot be measured by one similar European-wide standard, like for example the involvement, or not, in collective bargaining. On the contrary, this needs to be assessed in each country within the wider context and history of the social dialogue setting of the country. This justifies an approach where national representativeness criteria are taken into consideration, when considering the status of trade unions and employers’ organisations. For the data collection of the trade unions and employers’ organisations in each country, a specific national expert is collecting information about the representativeness of these organisations in that country. This data collection includes the meaning of representativeness in his or her national reporting. The reason for this procedure is that it is hard for one single researcher to grasp those different meanings in each of the different situations.

The different types of legitimacy distinguished by Weber [

17] may also help to understand the third representativeness criterium: national trade social partner organisations need adequate internal structures to ensure their effective participations in the European social dialogue [

38] or in Commission Consultations. Durkheim would have considered whether European social partner organisations can have their own reasons as a group, beyond the sum of the interests of each individual member organization. This would not only depend on the type of leadership, but also on internal structures and whether decision-making happens based on unanimity, majority voting, or as a form of organic solidarity, where interdependencies help to overcome internal differences.

Durkheim [

18] distinguishes mechanic solidarity based on similarities, from organic solidarity that is based on interdependency between different specializations, which also helps to better understand sector relatedness. Mechanic solidarity is found in the food and drink sector, where for each different type of food product specific associations exist, but also organic solidarity in umbrella organisations covering all types of food and drink production together. At the European level, FoodDrinksEurope is an umbrella organisation covering the employers of the entire sector, while there are also specific European associations for different food products and for different types of drinks.

Mechanical solidarity can also be found in the audiovisual sector, where different employers’ organisations cover the producers of movies or television programs on the one hand and the broadcasters on the other hand. Those producers are mostly smaller companies, while the broadcasters are larger companies, either formerly state-owned broadcasters, or commercial ones. The formerly state-owned broadcasters are represented by the European Broadcasting Union (EBU), while the commercial ones are represented by the Association of Commercial Television in Europe (ACT). The producers are represented by the International Federation of Film Producers’ Associations (FIAPF) and the European Audiovisual Production Association (CEPI). The employers of the radios are represented by the Association of European Radios (AER). Also, at the trade union side, there are different European trade union organisations for journalists, musicians, actors, and technicians and all other employees in the sector that are represented by UNI Europa—Media, Entertainment & Arts (EURO-MEI). The journalists are organised in the European Federation of Journalists (EFJ), the musicians in the International Federation of Musicians (FIM), and the actors in the International Federation of Actors (FIA).

A good example of organic solidarity can be found in the three parts of the civil aviation sector, i.e., the airlines, the air traffic controllers, and the ground handling activities. These three are strongly interdependent, although their activities are very different. Some professions, like pilots and air traffic controllers, have very specific trade union organisations, while the European Transport Federation is organizing all employees in the sector.

It is not because positivists ignore this subjective meaning and interpretation that their contribution is not valuable here. Positivists like Emile Durkheim look at representativeness as a fact that can be counted and calculated like in mathematics. This is how the number of trade union members is divided by the total number of employees in a company or a sector to calculate trade union density rates. In a similar way, the number of affiliated trade unions to a European trade union organisation are counted and divided by the total number of trade unions in a sector to calculate the organisational density rate. This is clearly a positivist approach of studying representativeness.

Furthermore, positivists consider social realities as facts that can be tested and verified, like as it is obtained in chemistry and physics. Positivism, applied to representativeness studies, gives the collected data after they are verified by social partners and cross-checked by different actors, in an iterative process, the status as proven facts. This transforms a collection of data from each of the 27 EU member states into a report that is after its final evaluation by all the actors involved considered as a picture, mapping the reality as it is at that moment in time, based on the available information. This process has, however, its limitations one should be aware of. When it comes to membership data, the membership databases of trade unions or employers’ organisations may be for all their members together, without specifying which one is active in a particular sector and which one is active in another sector. In some countries, such a database can exist at the regional level, without a possibility to gather the data from the different regions together to get the number for the entire country, as there is no willingness to disclose such political sensitive information. For these reasons, there are often only estimates communicated when it comes to the number of members. The reliability of the calculated density rates based on such estimates can be questioned. Allowing different organisations from each country to check and cross-check the data from all the organisations of that country is a form of triangulation in the methodology aimed at increasing the reliability of the findings in representativeness studies.

Robert K. Merton [

19] points also at the importance of the boundaries or limitations of representativeness. This happens by comparing the members with the different types of organisations that are not affiliated to European social partner organisation and are as such not represented in the European Sector Social Dialogue Committee (ESSDC). Merton would also mention former members that have stopped their membership; those that are not yet members, but interested in joining; and those that are indifferent, not interested in membership. This underscores the importance of listing the relevant national organisations not represented by European social partner organisations, or those that are affiliated to other European organisations that are not involved in the ESSDC, but nevertheless have some representativeness.

Membership of one employers’ organisation in the European employers’ organisation is considered as one unit that has the same value, as the membership of another organisation. The meaning, but also the value of each membership can, however, differ, which positivism does not allow including in its calculations. For example, the membership of the largest companies in a sector as corporate members in an employers’ organisation is of another nature than the membership of very small companies. The amount of membership fee they contribute to the functioning of the organisation will be larger for very large companies. Also, the influence larger companies have in the organisation will increase with their larger contributions in the budget of the organisation, because the organisation is also financially dependent on their membership. In the postal and courier sector, for example, the formerly state-owned postal company used to have a monopoly, but despite liberalization it will still have a very large part of the market share in the sector. That large national postal company can because of its size defend its interests on its own without being dependent on an employers’ organisation to gain sufficient collective weight in collective bargaining with trade unions, or in lobbying authorities. Their role as a member in an employers’ organisation is, however, crucial for their representativeness in terms of membership strength, but also in terms of their position in the sectoral industrial relations setting. The motivation of such large companies to become a member of the employers’ organisation can be to avoid that the employers’ organisation would undertake actions against the company’s interests. If this large company wants to undertake constructive initiatives, it can choose to do so at the company level, while its sector-level membership is more geared towards negative motivation, to avoid what is not wanted. A smaller company may have more constructive interests in being a member of the employers’ organisation, as it wants to be part of information and consultation procedures which as a smaller company it would not get, but as part of the employers’ organisations it may have the chance to advocate its interests. Attention for different kinds of motivations for membership in employers’ organisations is key in interpretative sociology.

Symbolic interactionism [

33] adds another interactive dimension to the meaning given to the processes of actors. Representativeness may, for example, also have a meaning in processes of mutual recognition, which are applied in, for example, Denmark, Finland, Sweden, and the UK [

9]. The importance and role of trade unions and employers’ organisations come from their willingness to recognize each other, cooperate in social dialogue, and in negotiating collective bargaining agreements. In a similar way, a national trade union or employers’ organisation, which at company level can have a relatively small degree of recognition in its industrial relations system, may gain extra importance through its involvement in social dialogue at a sector or higher cross sector level. Different views and expectations regarding membership and participation in an employers’ organisation may lead to tensions that lead to a dynamic of changing settings over time. Blumer [

33] thus correctly points out that industrial relations, and also representativeness, should not be seen as stable industrial relations settings written in stone, but as a potential dynamic, driven by different aspirations of different types of actors involved in it. An example of such different aspirations and how they can eventually change a European sectoral social dialogue setting can be found in the road transport sector that also covers the urban public transport activities. The trade unions and employers’ organisations from the urban public transport activities would prefer a separate ESSDC. The employers from the road transport sector would prefer to keep both activities together in one single ESSDC because they cover the freight road transport, the private sector passenger road transport, but also the private sector companies that operate the outsourced bus lines from the urban public transport activities.

Symbolic interactionism helps us to see these dynamics combining actions of cooperation in social dialogue and conflictual interactions in collective bargaining or industrial action (strikes). Interactions through shared participation in European social dialogue settings between employers and trade unions from one country that previously refused to dialogue or cooperate at the national level may also shift their views on each other’s organisations as a consequence of their involvement and cooperation at EU level.

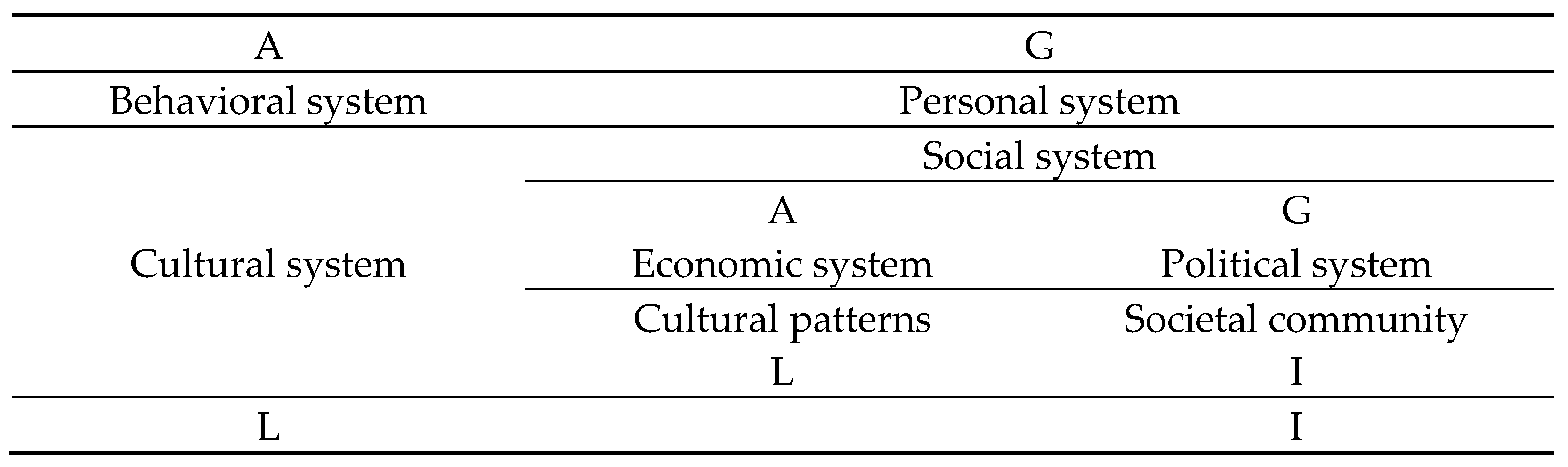

Functionalists, like Parsons [

22] and Merton [

19], also have a proper way to see different aspects of representativeness as interconnected. Each aspect would contribute to a different function in the entire system. An example of this can be found in the French approach of representativeness. Because of the low degree of trade union membership in France, there are clear rules, that do not look at membership, but at the outcome of the elections of trade union delegates for work councils at the company level to measure the relative representativeness of trade unions. The elections for workplace employee representatives thus have another function for the representativeness of an organisation—then the membership of workers in a trade union [

9]. Because there is a very low trade union membership rate in France, the proportion of elected trade union delegates at the workplaces can be seen as a functional equivalent for the membership strength, even though membership can be withdrawn and it can also include further involvement of the member in the organisation, while a vote in an election is only one single input in time. Membership can come with occasional or continuous internal participation in the trade union’s decision-making, and this can be the vehicle to provide for a negotiating mandate, or approve or disapprove draft agreements that have been reached, while a draft collective bargaining agreement can be endorsed in a ballot among all employees, not only the members, which subsequently serves the function of wider representativeness legitimizing the extension of the collective bargaining agreement to non-members.

Functionalists open the door for seeing evolutions, like in organisms with different functions in a body, that adjusts like species do in evolution theory. This functionalist approach to change over time is based on consensus in the system, whereas the critical sociology sees only the conflictual interests as drivers helping or hindering change. And as stated above, symbolic interactions realize to combine within its observations cooperative and conflictual interactions. But, let us first return to see how the functionalists perceive different elements of representativeness as parts of a harmonic consensus-based system.

The membership of a company in an employer’s organisation can be considered as a financial transaction of a paid membership fee, in return for the provided services to the affiliated companies. The budget of a European social partner organisation coming from the membership fees of the national affiliates determines the autonomy of the European organisation to develop its own policies beyond the sum of the individual interests of the affiliated organisations. The commitment of the member may be limited to the payment of the membership fees, or it may also involve political support, or the input of expertise, or a contribution to build coalitions within the organization, or its participation may also have the function of voting in a decision-making process. Structural functionalism opens our eyes for different formal types of membership and learns to distinguish full membership from an observer status. In the European Commission decision 500 [

16], there is a functionalist criteria prescribing that a European social partner needs to have appropriate structures that enable them to participate effectively in European social dialogue.

In the social exchange theory [

29], membership of a company in an employer organisation is a transaction where the membership fee is considered as a cost, and the benefits of the membership are balanced out in terms of added value of the membership fee investment. An example of this economic rational can be found in the UK system of trade union recognition at the company level [

9]. The management of a company may voluntarily recognize a trade union for collective bargaining negotiations, or this recognition can be refused. If it is refused, the trade union can request statutory recognition by the Central Arbitration Committee (CAC). If this CAC finds that 10% of the employees are unionized, a secret ballot is organized, of which the costs are equally distributed between the management and trade union(s). To obtain statutory recognition via this ballot, support is required of half of the voters, and the supportive voters need to be at least 40% of all the employees. Because of this arrangement of having to share the costs of the ballot, social exchange theory reassures us that actors will reason economically. Management will thus avoid the costs of a ballot and recognize a trade union voluntarily if it is clear that half of the employees are supportive to this. Trade unions, however, may refrain from calling for a ballot (and having to take up half of its costs) if they clearly do not have the required support among employees.

Social exchange theory assumes that member companies can more or less calculate whether the price of membership is acceptable in comparison with the risks of exclusion from decision-making if they refrain from membership. If the price is not acceptable, the union can save the membership fee, and the time to spend being involved in the employers’ organisation. This cannot reasonably be expected from individual members. Therefore, the importance of paying attention to the motivation to be a member stressed by interpretative sociologists cannot be ignored. Max Weber [

17], for example, does not only stress instrumental rational motivation and value-rationality, but also traditional grounds for membership. In social exchange theory, membership would mainly be assessed by referring to the goal rational motivation, which is a simplification of the reality. Exchange theory helps to see that cooperation of social partners in representativeness studies can be motivated by the reward of them being recognized as a representative social partner organisation. Historically, the 1951 European Coal and Steal Treaty included a strong institutionalized social dialogue, because both sectors were well organised, and had to be granted their European social dialogue structures in return for their approval and support for this European Coal and Steel Community.

Critical theory conceptualizes industrial relations as a power struggle. European social partner organisations are inclined to safeguard their position as most representative organisations and may want to overestimate their representativeness and try to influence researchers in this way. Simultaneously, the representativeness of rival organisations may be criticized or questioned, in an attempt to reduce this, which could help their relative importance.

The reticence or refusal of trade unions to reveal the number of their members may also be a way to protect themselves from the dominance of the system over their lifeworld, and their autonomy as a social partner organisation. The European commission as a system indeed introduced rules for European social dialogue and has made it dependent on its financing, subordinating the specificity of the lifeworld of some sectors and some specific actors. Critical sociology can thus encourage us to reflect openly on the methodology used in studying representativeness to check whether this methodology is not assuming an objectivism that is in fact re-enforcing the status quo of colonization practices. Consideration for potential adjustments to the standard methodology may also open up the analyses for other aspects of representativeness that empower the lifeworld and its actors. For example, the European commission has not created a new ESSDC between 2010 and 2022 [

26] and tried to gather other existing ones that are closely related, like for example the leather sector and the footwear sector. When the trade unions and employer organisations from the aerospace sector asked for a separate European sector social dialogue [

39], the reply from the European Commission [

40] indicated the expectation that the ongoing representativeness study for the metal sector would provide information about the social partner organisations’ representative for that sector. In this context, there was a demand to provide research findings that would justify and support the political decision to integrate aerospace within the metal sector of the European Social Dialogue Committee (ESSDC). While, for shipbuilding, a separate ESSDC exists [

41], whereas in principle these economic activities are also part of the scope of the metal sector of the ESSDC. Another example is the establishment of a European social dialogue for the football sector in 2008, while several years before efforts to make a European social dialogue for all sports failed. Habermas would point at the importance of huge amounts of money involved in the lifeworld of professional football to explain this. While for the power aspect, the importance of the capacity to negotiate needs to be studied in each representativeness study. Article 155 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union [

42] gives social partners the power to make agreements that can be implemented as a European Council Directive, for which no vote in the European Parliament is needed, because the representativeness study legitimizes the decision-making power of social partners to regulate the working conditions in their sector.

Symbolic interactionism indicates that industrial relations research needs to consider the changes in the sectors and the changes aspired in the relations and in the working conditions in the sector. Studying the representativeness of social partners should also include the dynamics in the sector, the aspirations and tensions. Examples of such changing settings can be found in the postal sector and in the telecom sector. Historically, the postal sector was dominated by the former state-owned post companies that are all affiliated to PostEurop. Since the postal sector has been liberalized, there are many other courier companies, and some of the formerly state-owned companies are now competing with the incumbents in other countries. The package delivery activities of courier companies is in fact not much different from the last mile delivery from freight road transport, bringing the postal sector and the road transport sector towards each other. Another example is the telecom sector, which historically was also dominated by state-owned monopolists. Here we find liberalization, but also technical changes that brought changing settings of the sector. Nowadays, telephones are not only mobile, but also more like computers, which has brought the IT and ICT sectors to merge with the telecom sector as one.