Vertical Educational (Mis)match and Inclusive Growth: Theoretical Conceptualizations and Evidence from a European Perspective

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. A Systematic Glimpse at Previous Literature

3. Theoretical Considerations

3.1. Skills/Educational Mismatch Through the Lens of the Capability Approach

3.2. Inclusive Growth

4. Data and Research Strategy

4.1. Data and Measures

- If AttainedEdu = ModalEduOcc, they are defined as matched.

- If AttainedEdu > ModalEduOcc, we classify the individuals as being vertically mismatched above.

- If AttainedEdu < ModalEduOcc, we classify them as vertically mismatched below.

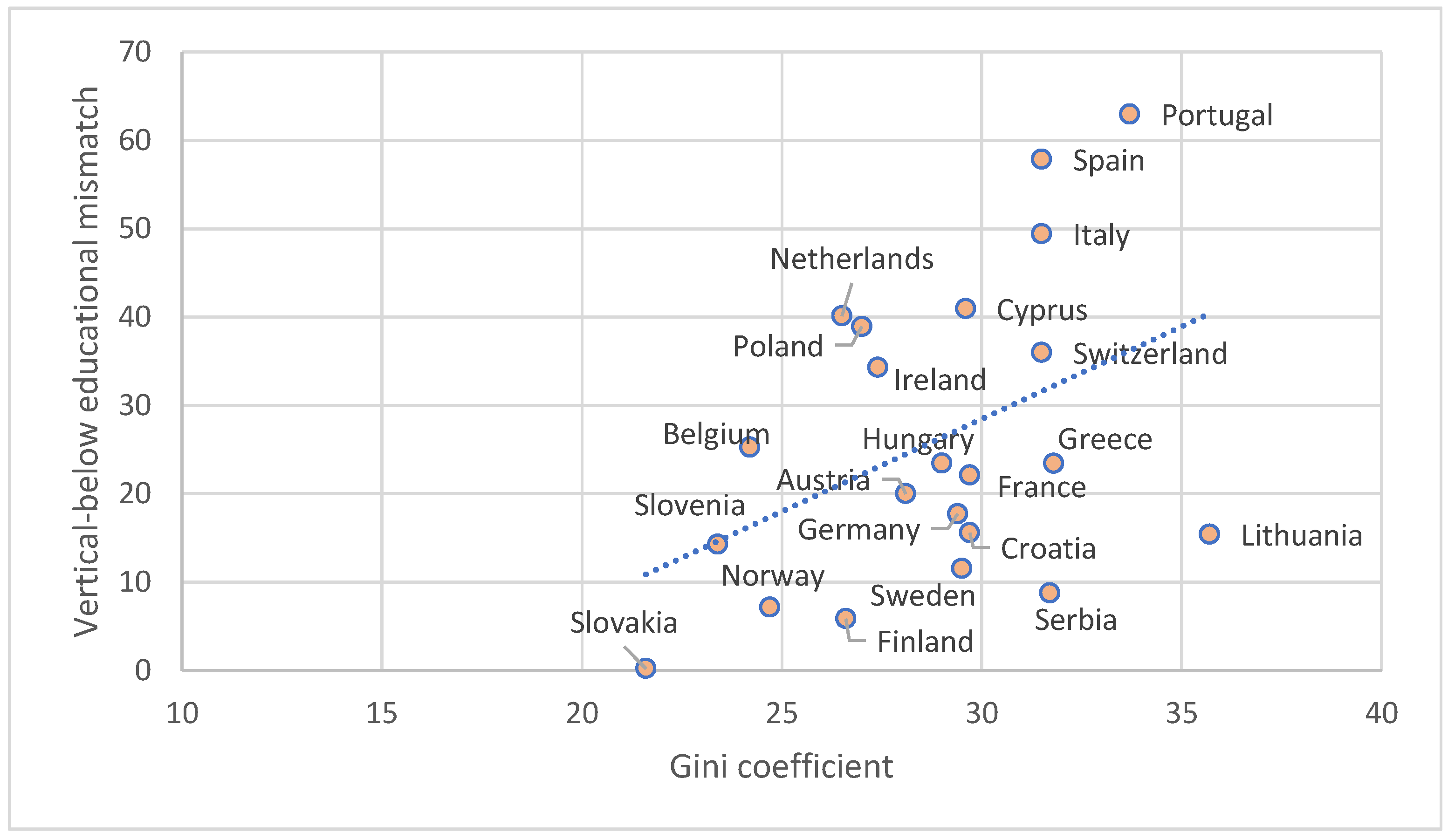

- Gini coefficient of equivalized disposable income. It is considered to be the best-known and the most common measure of income inequality, and the higher the Gini coefficient, the more unequal the income distribution in a given country is [76,77]. More specifically, it ranges between 0 and 100 and gives the extent to which the distribution of income within a country deviates from a perfectly equal distribution. A value of 0 means that income is distributed equally across the population, whereas 100 means that only one person receives all the income in the country (https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Living_conditions_in_Europe_-_income_distribution_and_income_inequality#Income_inequality). Source: Eurostat. Data code: ilc_di12 [Accessed on 11 April 2025].

- At-risk-of-poverty rate by poverty threshold. It is an income and living conditions indicator, which measures the at-risk-of-poverty rate (cut-off point: 60% of median equivalized income after social transfers). Its unit of measure is a percentage; the higher it is, the greater is the poverty in a given country. Source: Eurostat. Data code: ilc_li02 [Accessed on 11 April 2025].

- People at risk of poverty or social exclusion. It is used as a measure of poverty linked with the EU2030 targets. Its unit of measure is also a percentage. Source: Eurostat. Data code: ilc_peps01n [Accessed on 11 April 2025].

- In-work at-risk-of-poverty rate. It refers to the percentage of people in the total population from 18 to 64 years of age who declared themselves to be working (employed or self-employed) and who are at risk of poverty (i.e., with an equivalized disposable income below the risk-of-poverty threshold, which is set at 60% of the national median equivalized disposable income (after social transfers). Source: Eurostat. Data code: ilc_iw01 [Accessed on 11 April 2025].

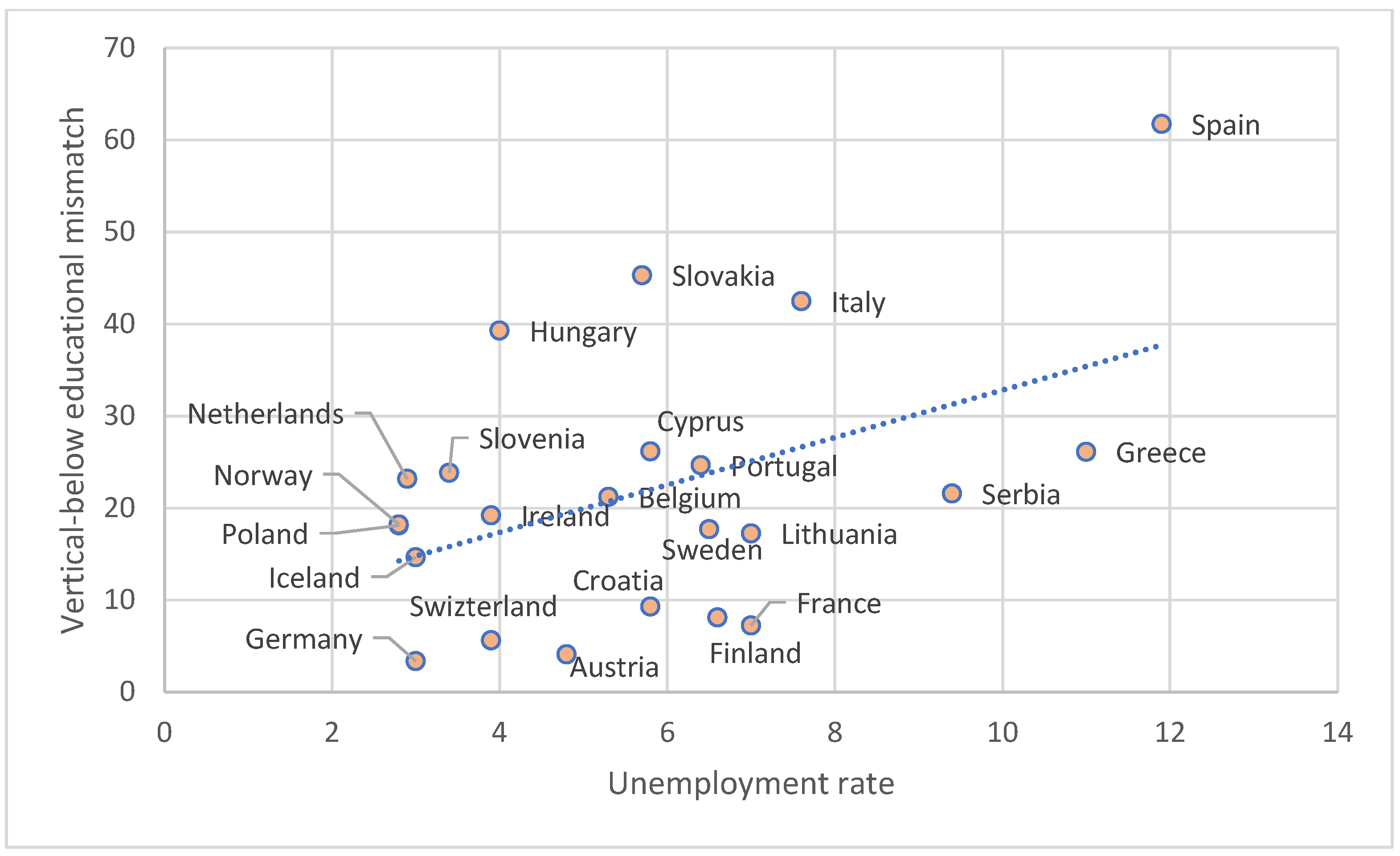

- Unemployment rate. It refers to the percentage of unemployment among the population aged 20 to 64 years in the labor force. Source: Eurostat. Data code: une_rt_a [Accessed on 11 April 2025].

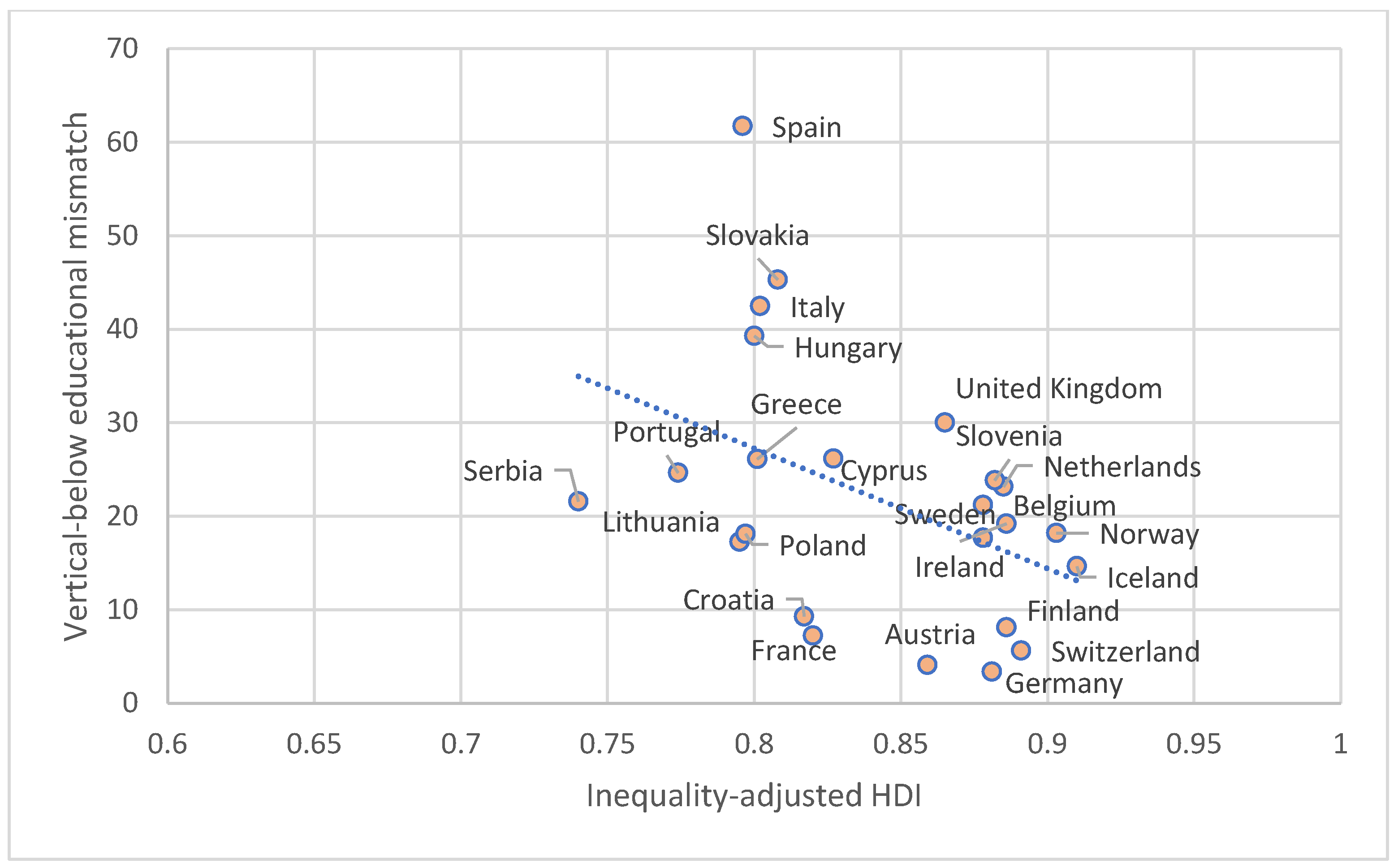

- Inequality-adjusted HDI. It is designed to adjust the Human Development Index value for inequality within countries in each of its components (health, education, and income)4 [17]. This index looks beyond the average progress of a country in terms of longevity, education, and income to show how these achievements are distributed among its residents. It ranges between 0 and 1, where the value of 1 means the best possible level of human development when inequality is accounted for.

4.2. Research Strategy

4.3. Limitations of the Analyses

5. Results

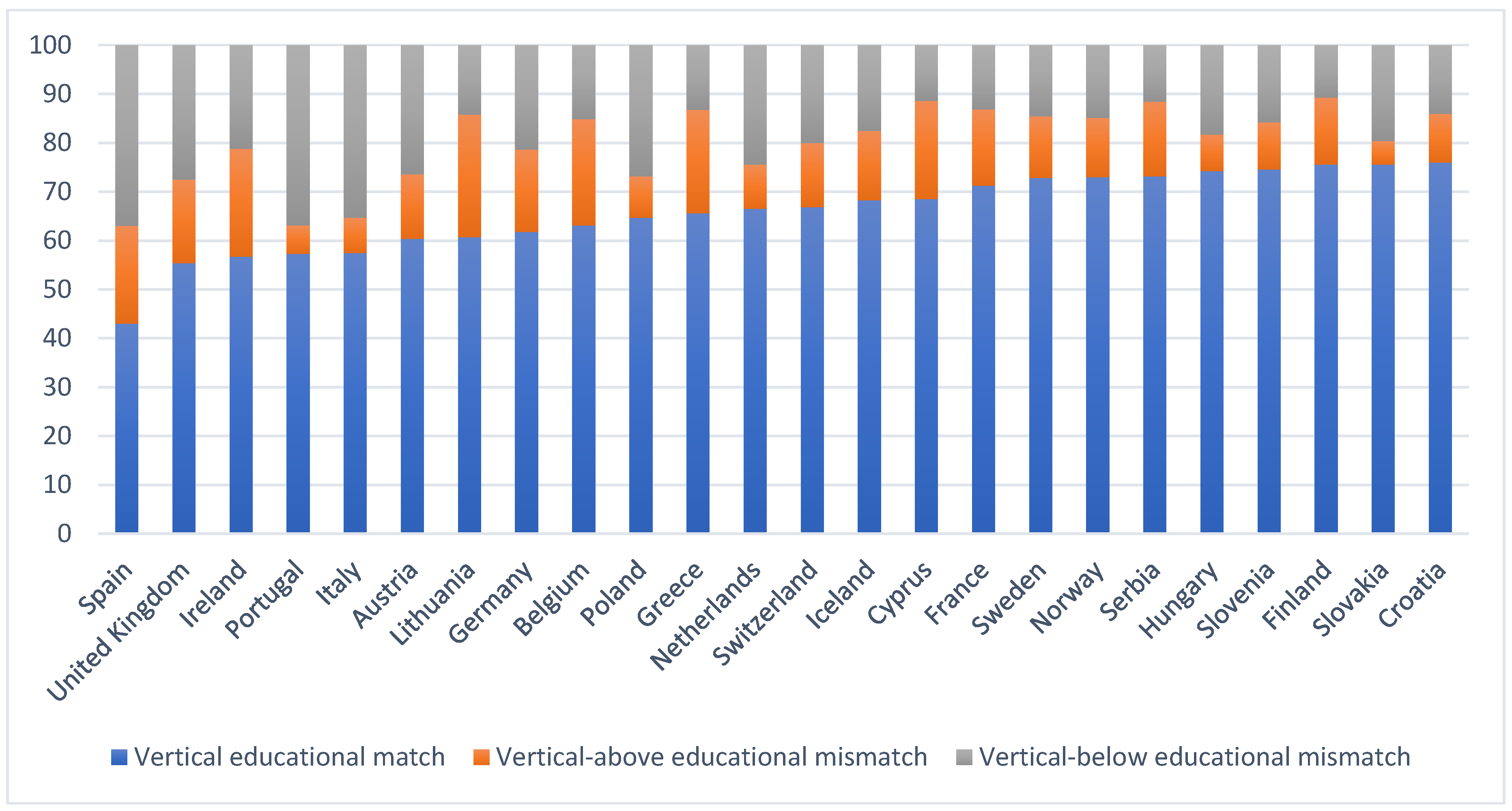

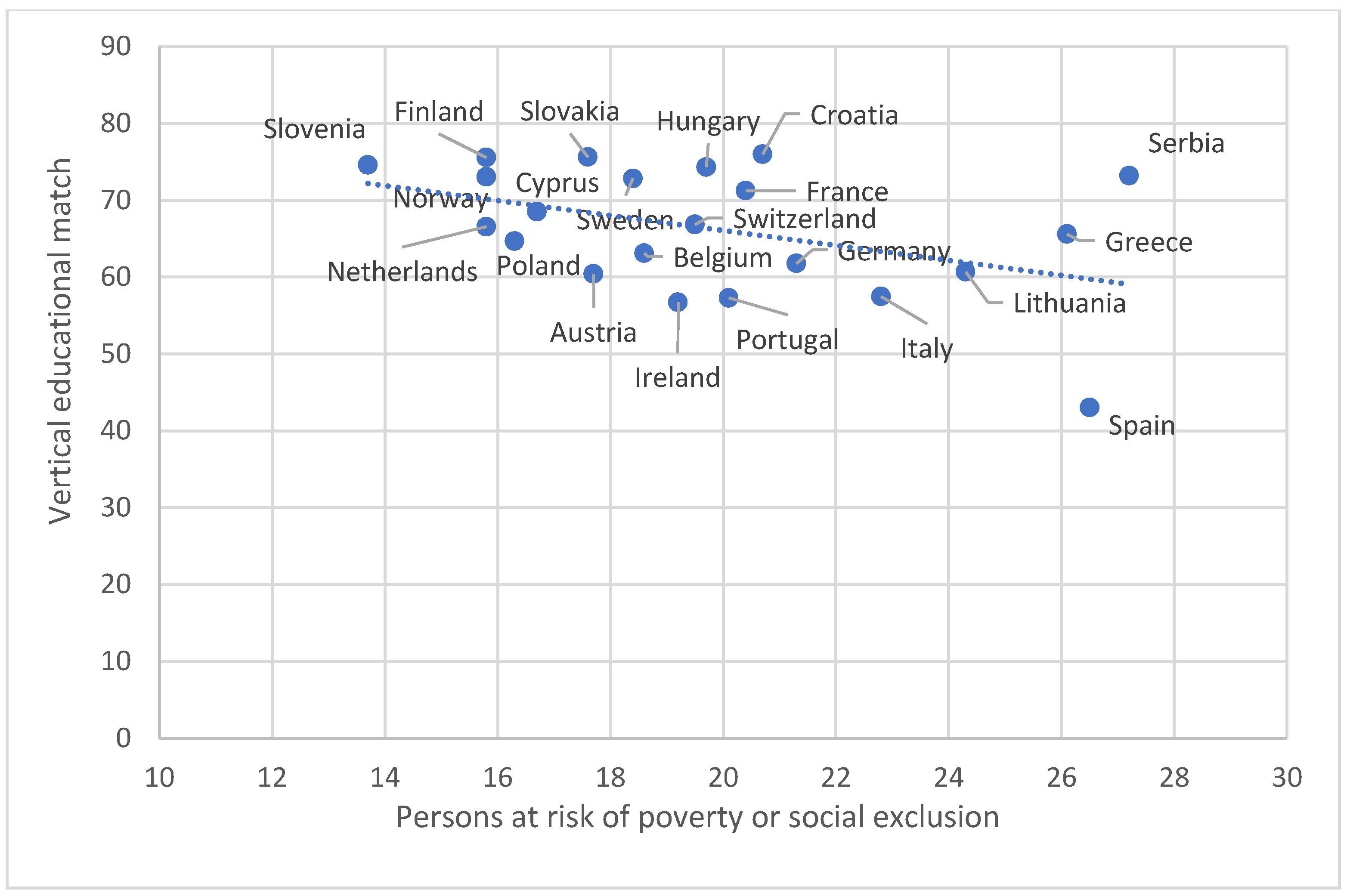

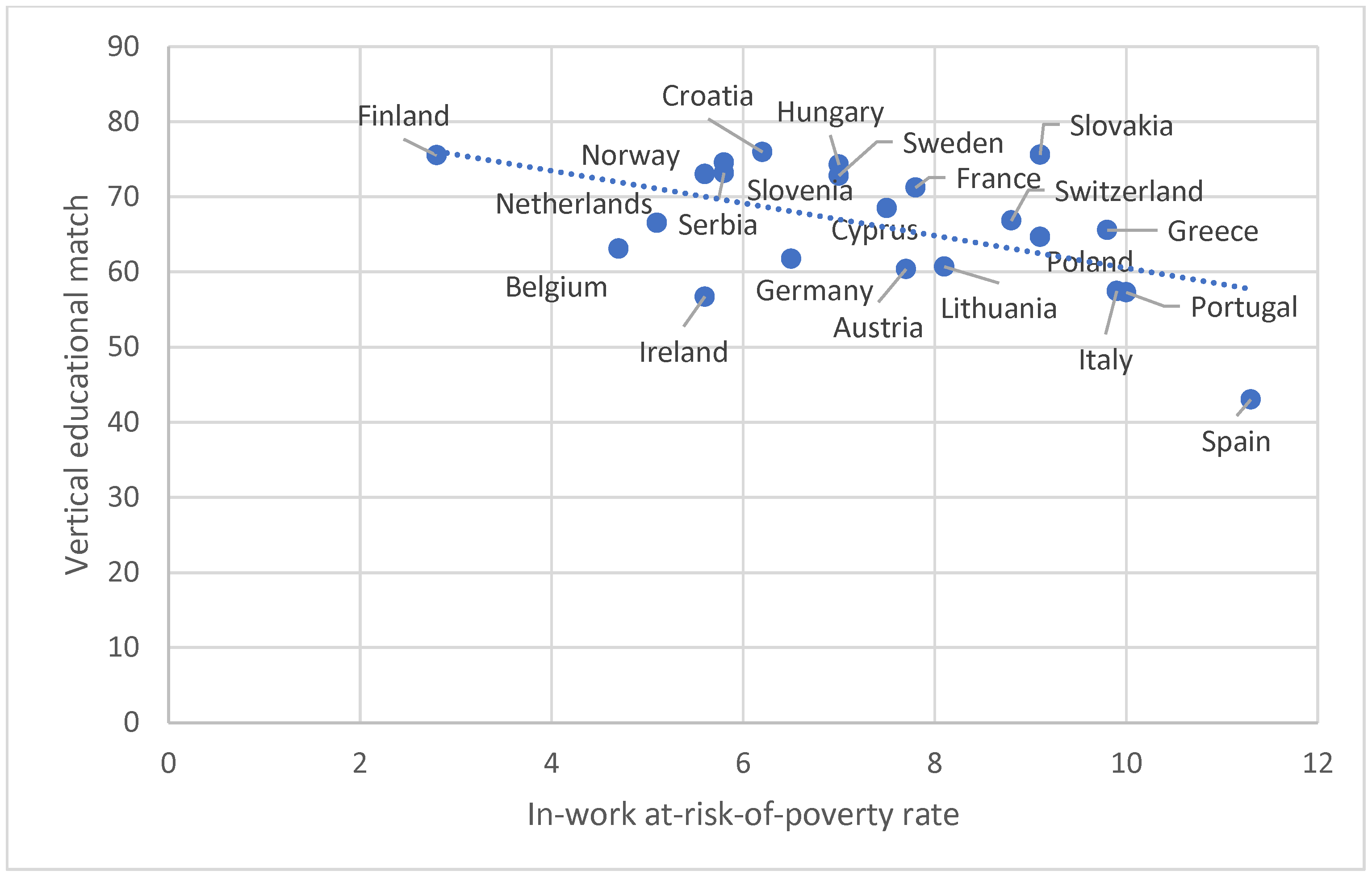

5.1. Vertical Educational Match

5.2. Vertical-Above Educational Mismatch

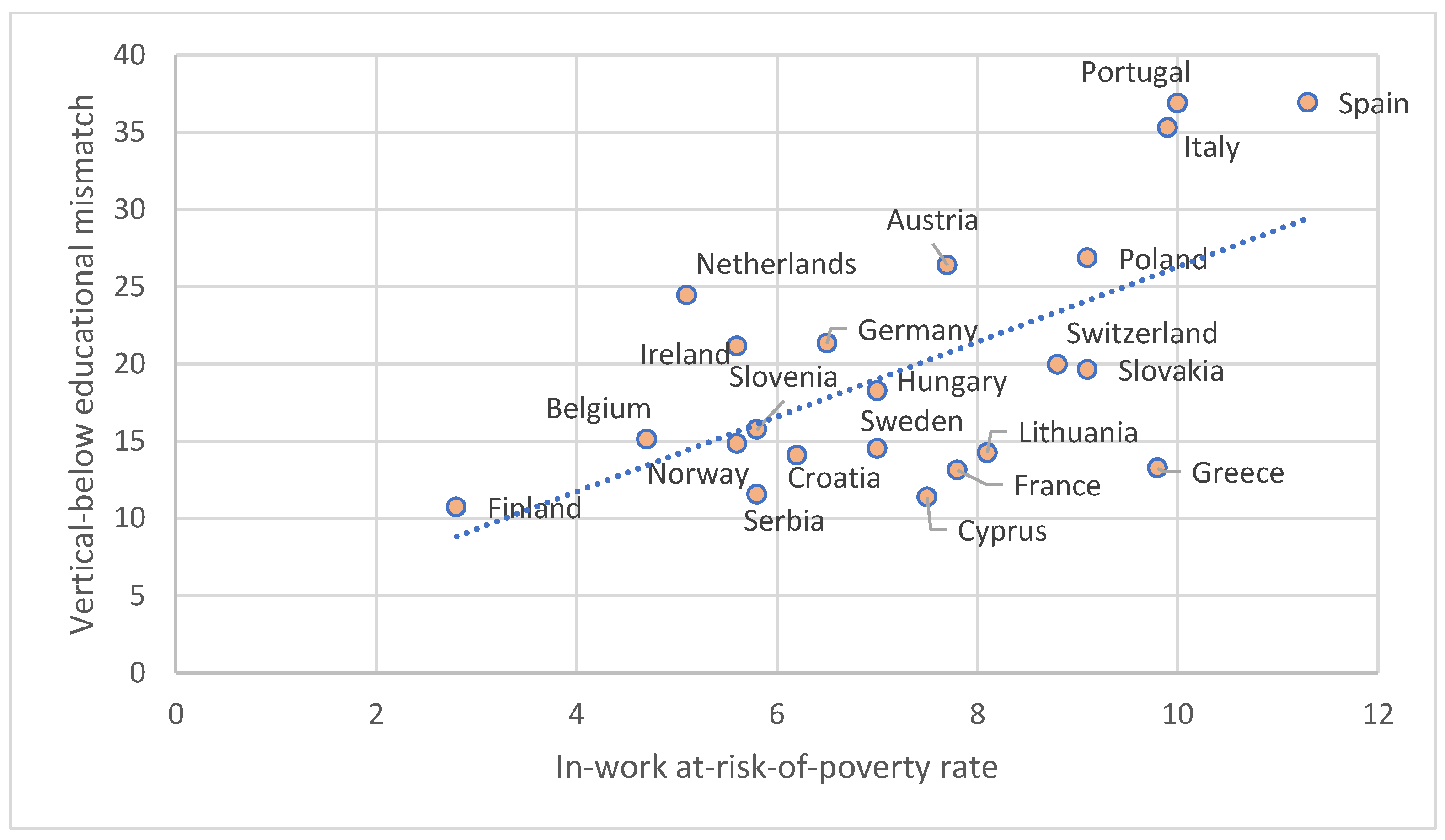

5.3. Vertical-Below Educational Mismatch

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Country | Gini Coefficient of Equivalised Disposable Income | At-Risk-of-Poverty Rate by Poverty Threshold | In-Work at-Risk-of-Poverty Rate | Persons at Risk of Poverty or Social Exclusion (%) | Unemployment Rate | Inequality-Adjusted HDI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Austria | 28.1 | 14.9 | 7.7 | 17.7 | 4.8 | 0.859 |

| Belgium | 24.2 | 12.3 | 4.7 | 18.6 | 5.3 | 0.878 |

| Switzerland | 31.5 | 16.4 | 8.8 | 19.5 | 3.9 | 0.891 |

| Cyprus | 29.6 | 13.9 | 7.5 | 16.7 | 5.8 | 0.827 |

| Germany | 29.4 | 14.4 | 6.5 | 21.3 | 3 | 0.881 |

| Spain | 31.5 | 20.2 | 11.3 | 26.5 | 11.9 | 0.796 |

| Finland | 26.6 | 12.2 | 2.8 | 15.8 | 6.6 | 0.886 |

| France | 29.7 | 15.4 | 7.8 | 20.4 | 7 | 0.82 |

| United Kingdom | - | - | - | - | - | 0.865 |

| Greece | 31.8 | 18.9 | 9.8 | 26.1 | 11 | 0.801 |

| Croatia | 29.7 | 19.3 | 6.2 | 20.7 | 5.8 | 0.817 |

| Hungary | 29 | 13.1 | 7 | 19.7 | 4 | 0.8 |

| Ireland | 27.4 | 12 | 5.6 | 19.2 | 3.9 | 0.886 |

| Iceland | - | - | - | - | 3 | 0.91 |

| Italy | 31.5 | 18.9 | 9.9 | 22.8 | 7.6 | 0.802 |

| Lithuania | 35.7 | 20.6 | 8.1 | 24.3 | 7 | 0.795 |

| Netherlands | 26.5 | 13 | 5.1 | 15.8 | 2.9 | 0.885 |

| Norway | 24.7 | 11.5 | 5.6 | 15.8 | 2.8 | 0.903 |

| Poland | 27 | 14 | 9.1 | 16.3 | 2.8 | 0.797 |

| Portugal | 33.7 | 17 | 10 | 20.1 | 6.4 | 0.774 |

| Serbia | 31.7 | 19.9 | 5.8 | 27.2 | 9.4 | 0.74 |

| Sweden | 29.5 | 16.1 | 7 | 18.4 | 6.5 | 0.878 |

| Slovenia | 23.4 | 12.7 | 5.8 | 13.7 | 3.4 | 0.882 |

| Slovakia | 21.6 | 14.3 | 9.1 | 17.6 | 5.7 | 0.808 |

| 1 | |

| 2 | See: https://europeansocialsurvey.org/news/article/second-release-round-11-data-now-available (accessed on 11 April 2025). |

| 3 | More specifically, we differentiate between four occupational groups distinguished based on ISCO broad categories at the single-digit level: high-skilled white-collar workers (ISCO 1–3), low-skilled white-collar workers (ISCO 4–5), high-skilled blue-collar workers (ISCO 6–7), and low-skilled blue-collar workers (ISCO 8–9). |

| 4 | Its values are as of 2022 because it was the latest release of the index available at the moment of the study. |

References

- Cerra, V. An inclusivse growth framework. In How to Achieve Inclusive Growth; Cerra, V., Eichengreen, B., El-Ganainy, A., Schindler, M., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2022; pp. 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiglitz, J. The Price of Inequality. How Today’s Divided Society Endangers Our Future; W.W. Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson, R.; Pickett, K. The Spirit Level: Why More Equal Societies Almost Always Do Better; Allen Lane: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Comin, F. Beyond the HDI? Assessing Alternative Measures of Human Development from a Capability Perspective; UNDP Human Development Report Office: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ianchovichina, E.; Lundstrom, S. Inclusive Growth Analytics: Framework and Application; Policy Research Working Paper 4851; The World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2009; Available online: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/771771468180864543/Inclusive-growth-analytics-framework-and-application (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Ranieri, R.; Ramos, A.R. Inclusive Growth: Building Up a Concept; Working Paper 104; International Policy Centre for Inclusive Growth, United Nations Development Programme: Brasilia, Brazil, 2013; Available online: https://ipcid.org/sites/default/files/pub/en/IPCWorkingPaper104.pdf (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Cerra, V.; Eichengreen, B.; El-Ganainy, A.; Schindler, M. (Eds.) How to Achieve Inclusive Growth; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Saher, L.; Tabák, L.; Lyeonov, S.; Vasa, L. Inclusive growth: Literature review. J. Int. Stud. 2024, 1, 205–232. Available online: https://www.ceeol.com/search/article-detail?id=1236169 (accessed on 15 November 2024). [CrossRef]

- Brunello, G.; Wruuck, P. Skill shortages and skill mismatch: A review of the literature. J. Econ. Surv. 2021, 35, 1145–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roosmaa, E.-L.; Saar, E.; Martma, L. Education Mismatch in European Countries During the 2008 Financial Crisis and After That: Determinants by Occupational Groups and the Mismatch on Salaries; RASI Toimetised nr 23; Tallinna Ülikool: Tallinn, Estonia, 2023; Available online: https://www.tlu.ee/sites/default/files/Instituudid/%C3%9CTI/RASI/2023_RASI%20toimetised%20nr%2023_Education%20mismatch%20in%20European%20countries%20during%20the%202008%20financial%20crisis%20and%20after%20that%20determinants%20by%20occupational%20groups%20and%20the%20mismatch%20on%20salaries.pdf (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Neycheva, M. Qualification (mis)match for upper secondary and higher education. Soc. Sci. 2021, 10, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schofer, E.; Meyer, J.W. The worldwide expansion of higher education in the twentieth century. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2005, 70, 898–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantwell, B.; Marginson, S.; Smolentseva, A. (Eds.) High Participation Systems of Higher Education; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Desjardins, R. Rewards to Skill Supply, Skill Demand and Skill-mismatch. Studies Using the Adult Literacy and Life Skills Survey; Lund Economic Studies No 176; Lund University: Lund, Sweden, 2014; Available online: https://lup.lub.lu.se/search/publication/4350627 (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- McGuinness, S.; Pouliakas, K.; Redmond, P. Skills mismatch: Concepts, measurement and policy approaches. J. Econ. Surv. 2018, 32, 985–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ESS Round 11: European Social Survey European Research Infrastructure (ESS ERIC) ESS11—Integrated File, 2nd ed.; [Data Set]; Sikt—Norwegian Agency for Shared Services in Education and Research: Bergen, Norway, 2024. [CrossRef]

- UNDP. Human Development Report 2023/2024. Breaking the Gridlock: Reimagining Cooperation in a Polarized World; UNDP: New York, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Cedefop. Insights into Skill Shortages and Skill Mismatch: Learning from Cedefop’s European Skills and Jobs Survey; Cedefop Reference Series No 106; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2018; Available online: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2801/645011 (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- McGuinness, S.; Redmond, P.; Staffa, E.; Devlin, A.; Whelan, A. 15: Skills mismatch: What do we already know and what do we need to know? In Handbook of Education and Work; Maarten, H.J., Wolbers, M.H.J., Verhaest, D., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2025; pp. 318–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cedefop. Skill Mismatch in Europe Europe’s Challenge Is Not Just to Improve Skill Levels, But to Match People with the Right Skills to the Right Jobs. Briefing Note; Cedefop: Thessaloniki, Greece, 2010; Available online: https://www.cedefop.europa.eu/files/9023_en.pdf (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- McGuinness, S. Overeducation in the labour market. J. Econ. Surv. 2006, 20, 387–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delaney, J.; McGuinness, S.; Poulakis, K.; Redmond, P. Educational expansion and overeducation of young graduates: A comparative analysis of 30 European countries. Oxf. Rev. Educ. 2020, 46, 10–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, T.W. Investment in human capital. Am. Econ. Rev. 1961, 51, 1–17. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1818907 (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Mincer, J. Investment in human capital and personal income. J. Political Econ. 1958, 66, 281–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kautz, T.; Heckman, J.I.; Diris, R.; ter Weel, B.; Borghans, L. Fostering and Measuring Skills: Improving Cognitive and Non-Cognitive Skills to Promote Lifetime Success; IZA Discussion Paper No. 8696; IZA: Bonn, Germany, 2014; Available online: https://docs.iza.org/dp8696.pdf (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Heckman, J.; Corbin, C. Capabilities and Skills. J. Hum. Dev. Capab. 2016, 17, 342–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thurow, L. Generating Inequality; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch, F. Social Limits to Growth; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, R. The Credential Society: A Historical Sociology of Education and Stratification; First Printing Edition; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Bryson, J. Putting skill in its place. J. Educ. Work 2015, 28, 551–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergin, A.; Delaney, J.; Handel, M.; McGuinness, S.; Kupets, O.; Pouliakas, K.; Redmond, P. Skills and Jobs Mismatches in Low- and Middle-Income Countries; International Labour Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Verhaest, D.; van der Velden, R. Cross-country differences in graduate overeducation. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 2013, 29, 642–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhaest, D.; Sellami, S.; van der Velden, R. Differences in horizontal and vertical mismatches across countries and fields of study. Int. Labour Rev. 2017, 156, 2–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handel, M.J.; Valerio, A.; Sanchez Puerta, M. Accounting for Mismatch in Low- and Middle-Income Countries; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sparreboom, T.; Staneva, A. Is Education the Solution to Decent Work for Youth in Developing Economies? Identifying Qualifications Mismatch from 28 School-to-Work Transition Surveys; Work4Youth Publication Series No. 23; International Labour Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, J.; van der Velden, R. Educational mismatches versus skill mismatches: Effects on wages, job satisfaction, and on-the-job search. Oxf. Econ. Pap. 2001, 53, 434–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevalier, A.; Lindley, J. Overeducation and the skills of UK graduates. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. A Stat. Soc. 2009, 172, 307–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, A. Inequality Reexamined; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, A. Development as Freedom; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Nussbaum, M. Creating Capabilities. The Human Development Approach; The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press: Cambridge, UK; London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, A. Editorial: Human capital and human capability. World Dev. 1997, 25, 1959–1961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, A. The Idea of Justice; The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Robeyns, I. Wellbeing, Freedom and Social Justice. The Capability Approach Re-Examined; Open Book Publishers: Cambridge, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Boyadjieva, P.; Ilieva-Trichkova, P. Adult Education as Empowerment: Re-Imagining Lifelong Learning Through the Capability Approach, Recognition Theory and Common Goods Perspective; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Thapa, B.K. Capability approach to skill: Bridging the disciplinary differentials over conceptualizing skill. J. Tech. Vocat. Educ. Train. 2021, 1, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Støren, L.A.; Arnesen, C.Å. Winners and losers. In The Flexible Professional in the Knowledge Society; Allen, J., van der Velden, R., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2011; pp. 199–240. [Google Scholar]

- Laruffa, F. What is a capability-enhancing social policy? Individual autonomy, democratic citizenship and the insufficiency of the employment-focused paradigm. J. Hum. Dev. Capab. 2020, 21, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, A. Inequality, unemployment and contemporary Europe. Int. Labour Rev. 1997, 136, 160–164. [Google Scholar]

- Chiappero-Martinetti, E.; Sabadash, A. Integrating human capital and human capabilities in understanding the value of education. In The Capability Approach; Ibrahim, S., Tiwari, M., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2014; pp. 206–230. [Google Scholar]

- Ravallion, M.; Chen, S. Measuring pro-poor growth. Econ. Lett. 2003, 78, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klasen, S.; Kneib, T.; Bue, M.; Prete, V. What’s behind pro-poor growth? An investigation of its drivers and dynamics. J. Econ. Inequal. 2024, 23, 43–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinley, T. Inclusive Growth Criteria and Indicators: An Inclusive Growth Index for Diagnosis of Country Progress; ADB Sustainable Development Working Paper Series No. 14; Asian Development Bank: Metro Manila, Philippines, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Anand, R.; Mishra, S.; Peiris, S.J. Inclusive Growth: Measurement and Determinants; The Economic Premise Note Series No. 122; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- James, C.; Devaux, M.; Sassi, F. Inclusive Growth and Health; OECD Health Working Paper No. 103; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samans, R.; Blanke, J.; Corrigan, G.; Hanouz, M. The Inclusive Growth and Development Report 2017; World Economic Forum: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Europe 2020: A Strategy for Smart, Sustainable, and Inclusive Growth; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Inclusive Growth at a Crossroads. Part One of Strengthening Inclusion and Facilitating the Green Transition; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hay, C.; Hunt, T.; McGregor, J.A. Inclusive growth: The challenges of multidimensionality and multilateralism. Camb. Rev. Int. Aff. 2022, 35, 888–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, A.; Das, D. Inclusive growth: Economics as if people mattered. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2018, 19, 756–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNCTAD. Stark Contrast in Inclusive Growth: Progress Towards Equal Opportunities Needed Everywhere; SDG Pulse; 2022. Available online: https://sdgpulse.unctad.org/inclusive-growth/ (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Pritchett, L. Where has all the education gone? World Bank Econ. Rev. 2001, 15, 367–391. Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/17434 (accessed on 15 November 2024). [CrossRef]

- Sunde, U.; Vischer, T. Human capital and growth: Specification matters. Economica 2015, 82, 368–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atiq-ur-Rehman Rauf, A.; Khan, G. Human capital-growth nexus: The skill mismatch. Intellect. Econ. 2021, 15, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kampelmann, S.; Mahy, B.; Rycx, F.; Vermeylen, G. Over-, required, and undereducation: Consequences on the bottom lines of Firms. Labour 2020, 34, 80–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuinness, S.; Sloane, P.J. Labour market mismatch among UK graduates: An analysis using Reflex data. Econ. Educ. Rev. 2011, 30, 130–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz de Bustillo Llorente, R.; Sarkar, S.; Sebastian, R.; Antón, J.-I. Education mismatch in Europe at the turn of the century: Measurement, intensity and evolution. Int. J. Manpow. 2018, 39, 977–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boll, C.; Leppin, J.S.; Schömann, K. Who Is Overeducated and Why? Probit and Dynamic Mixed Multinomial Logit Analyses of Vertical Mismatch in East and West Germany; Papers on Multidisciplinary Panel Data Research, No. 661; SOEP: Berlin, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Cedefop. Setting Europe on Course for a Human Digital Transition: New Evidence from Cedefop’s Second European Skills and Jobs Survey; Cedefop Reference Series No. 123; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2022; Available online: https://www.cedefop.europa.eu/cs/publications/3092 (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Flisi, S.; Goglio, V.; Meroni, E.C.; Rodrigues, M.; Vera-Toscano, E. Measuring occupational mismatch: Overeducation and overskill in Europe—Evidence from PIAAC. Soc. Indic. Res. 2017, 131, 1211–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capsada-Munsech, Q. Measuring overeducation: Incidence, correlation and overlaps across indicators and countries. Soc. Indic. Res. 2019, 145, 279–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiglitz, J.E.; Sen, A.; Fitoussi, J.-P. Mismeasuring Our Lives. Why GDP Doesn’t Add Up? The Report by the Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress; The New Press: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Chancel, L.; Thiry, G.; Demailly, D. Beyond-GDP Indicators: To What End? Study N 04/14; IDDRI: Paris, France, 2014; Available online: https://www.iddri.org/sites/default/files/import/publications/st0414en.pdf (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Biggeri, M.; Mauro, V. Towards a more ‘Sustainable’ Human Development Index: Integrating the environment and freedom. Ecol. Indic. 2018, 91, 220–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoekstra, R. Replacing GDP by 2030: Towards a Common Language for the Well-Being and Sustainability Community; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- UNDP. Human Development Report, The Real Wealth of Nations: Pathways to Human Development; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Jeliazkova, M. The Polarized Bulgarian Society: Persistent Poverty and Toxic Inequalities; Polis Publishers: Sofia, Bulgaria, 2024. (In Bulgarian) [Google Scholar]

- Alkire, S.; Santos, M.E. Poverty and inequality measurement. In An Introduction to Human Development and Capability Approach: Freedom and Agency; Deneulin, S., Shanani, L., Eds.; Earthscan: London, UK; Steling, UK, 2009; pp. 121–161. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, J.D. Straightforward Statistics for the Behavioral Sciences; Brooks/Cole Publishing: Pacific Grove, CA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Salkind, N.J. Statistics for People Who (Think They) Hate Statistics, 4th ed.; Sage: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Anand, P.; Jones, S.; Donoghue, M.; Teitler, J. Non-monetary poverty and deprivation: A capability approach. J. Eur. Soc. Policy 2021, 31, 78–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Boyadjieva, P.; Ilieva-Trichkova, P. Vertical Educational (Mis)match and Inclusive Growth: Theoretical Conceptualizations and Evidence from a European Perspective. Societies 2025, 15, 113. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15040113

Boyadjieva P, Ilieva-Trichkova P. Vertical Educational (Mis)match and Inclusive Growth: Theoretical Conceptualizations and Evidence from a European Perspective. Societies. 2025; 15(4):113. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15040113

Chicago/Turabian StyleBoyadjieva, Pepka, and Petya Ilieva-Trichkova. 2025. "Vertical Educational (Mis)match and Inclusive Growth: Theoretical Conceptualizations and Evidence from a European Perspective" Societies 15, no. 4: 113. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15040113

APA StyleBoyadjieva, P., & Ilieva-Trichkova, P. (2025). Vertical Educational (Mis)match and Inclusive Growth: Theoretical Conceptualizations and Evidence from a European Perspective. Societies, 15(4), 113. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15040113