2. An Overview of the Contemporary Afghan and Romanian Cultures and Social Realities

Though both countries have extensive experience with autocratic regimes and are collectivistic cultures, in essence, there are huge discrepancies between them [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20]. As such, for most of the 20th century, both countries were ruled by dictatorships that established an atmosphere of terror and lack of opportunities for their people. Both countries followed the Soviet communist doctrine, Afghanistan from 1978 to 1992 and Romania from 1947 to 1989. After the communist regime, Romania chose a new path, becoming a democratic country and a member state of the European Union in 2007, whereas Afghanistan entered a stage characterised by instability and war, denial of human rights, particularly women’s and girls’ rights, and a lack of education, health and social assistance, which slightly improved between 2001 and 2021 during the American intervention in the country only to lose these benefits after the withdrawal of the foreign forces that provided some kind of stability and normality.

Although the communist regimes are perceived as autocratic, depriving the citizens of some, if not most, of their rights, in the case of Afghanistan, it was one of the few regimes, that tried to modernise the country, offering the Afghan population, irrespective of gender, equal rights to work, study, vote, stand as a political candidate at local or national elections, obtain medical or social assistance, to mention but a few advantages. Such a blooming and promising phase was also experienced during the 20-year American and NATO forces' intervention in Afghanistan. Nevertheless, the modernisation process unfolded mainly in the urban areas, the rural areas remaining highly traditional and patriarchal [

6,

15,

16]. The Afghan patriarchal social structure “defines and interprets religious teachings as masculine and in favour of men” [

16] (p. 65), being essentially an “anti-development and anti-modernization” trigger (Sajjadi 2012:238, cited in [

16] (p. 69). Afghan society has always been patriarchal, with short lapses into modernity. Consequently, men have always been given a higher status than women, the former being considered more valuable than the latter [

15,

16,

17,

21,

22]. This attitude is strengthened by the existence of

bacha posh, i.e., “girls dressed as boys” [

22] (p. 1). In other words, families that do not have boys are allowed to change the girl names into boy names and to dress and raise their girls as boys, thus having all the rights and liberties of the Afghan boys. This is tolerated and even encouraged only to wash away the shame that a family has to bear if it does not produce a male representative [

15,

22]. In such a cultural and social context, it is no surprise that boys and men are allowed to study and obtain an education, go to work, and provide for the family as opposed to girls and women who have to stay at home, take care of the household, wear a

burka whenever they leave their house or in front of other men, and learn about the world from their male counterparts. The difficulty arises when the family, for one reason or another, lacks a man to provide for it since women cannot go outside the house without a male relative to accompany them. Furthermore, most women lack education and have no professional qualification or official work permit to help the family survive [

15,

16,

17,

21,

22,

23]. Post-2021 Afghanistan is dominated by men, with women and girls having no rights at all. Nevertheless, even men lose their rights and get punished if they stand for women and girls because, in most Afghans’ opinion, women and girls may have rights only in Western cultures and not in Afghan culture, with such progressive attitudes being perceived as a threat to Afghan culture [

24,

25].

In Romania, as in any country in the European Union, women and girls do have the same rights as men and boys. Both genders may go to school, obtain an education, work side by side, benefit from medical and social care or stand as political candidates at elections. Women are allowed to go outside their homes unaccompanied, obtain jobs, learn and work in the same environment as men [

26,

27,

28]. Fundamentally, women and men have the same rights and liberties; they are equal in the eyes of the law and of society. Women do not have to wear a burka; in other words, they do not have to hide their body shape, their faces or hair from others.

Besides sharing a communist past and experience with autocratic regimes, the two countries have one more trait in common, namely, they are both collectivistic cultures [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20]. In other words, the group is more important than the individual; the individual is valuable only in relation to the group s/he belongs to. Each member of the group caters to the welfare of the community, fulfilling pre-established roles. As such, the social interconnectivity and interdependence are tighter in collectivistic cultures than in individualistic ones, the latter putting the individual well-being above the collective one. In other words, “[p]eople in collectivist societies are more likely to be interdependent and concerned about other people’s perceptions, while those in independentism societies are more concerned about individual identity” [

29] (p. 201). Consequently, collectivist cultures tend to resonate better with other people, i.e., to be more empathic. Nevertheless, the degree of collectivism or individualism differs from culture to culture (

Figure 2), being evaluated on a scale from 1 to 100 according to the Cultural Dimensions Index proposed by Geert Hofstede [

8], from less collectivistic to highly collectivistic.

Culture, however, is a dynamic concept and changes in time as society evolves technologically and economically, shifting the focus from survival to self-expression [

30,

31,

32]. The former defines poor societies, whereas the latter defines developed ones. Therefore, collectivistic cultures may gradually become individualistic ones as the country gets more prosperous. Such a situation has been noticed in Romania, whose scores in the World Values Survey point to a change in the younger generation’s cultural profile, from collectivistic to individualistic [

33], that has occurred after Romania’s integration into the European Union, a trend anticipated by David [

13] as well.

The deeply rooted collectivism and patriarchal traditions in Afghan culture, which have historically shaped gender roles and societal norms, also extend their influence into other domains, such as business ethics and healthcare, where cultural practices and systemic challenges further illustrate the stark contrasts between Afghan society and more individualistic, egalitarian cultures such as that of the United States.

Two studies highlight these contrasts in the realms of business ethics and healthcare. The first study, “A Cross-Cultural Comparison of Business Ethics Study with Respondents from Afghanistan, Pakistan, Iran, and the United States” [

34], explores how Afghan culture, with its collective and high-context nature, contrasts with the individualistic and rule-based culture of the United States. This comparison reveals how systemic challenges and cultural norms in Afghanistan lead to a greater tolerance for unethical practices such as bribery, while the US emphasises transparency and legal compliance. The second study [

35] focuses on the maternal healthcare experiences of Afghan refugee women in the US, illustrating how traditional Afghan cultural practices, such as gender roles and decision-making dynamics, differ from Western healthcare norms. In Afghanistan, women often lack prenatal care and face disrespectful treatment, while in the US, they appreciate attentive care but struggle with language barriers and discomfort with male providers. Afghan women rely on husbands for decision-making and transportation, and while they maintain cultural practices such as breastfeeding for two years, they are open to contraception but need more education.

3. Research Methodology

The focus of the study detailed below was on identifying the students’ awareness of the post-2021 situation in Afghanistan, their perception of the way in which the life of citizens, in general, and of women, in particular, has changed due to the current political regime, and the eagerness of the surveyed population to resonate with Afghan culture, be it in Romania or in Afghanistan. As such, the following research objectives have been set by the research team:

RO1. To determine the students’ levels of awareness concerning the situation of the population in Afghanistan following the establishment of the current political regime;

RO2. To determine the students’ perception of the situation of the female population in Afghanistan following the establishment of the current political regime;

RO3. To identify the students’ level of receptiveness to the Afghan cultural situation.

In order to achieve these objectives, a non-standardised 10-question (3 open-ended and 7 closed-ended) questionnaire was created, applying the Delphi Method [

36,

37], in which the experts were the students as co-researchers. Initially, 50 items were submitted for analysis to the group of students during the

Research Methods in Social Sciences course. After 4 iterations, the 33 items were selected, which make reference to the students’ level of awareness concerning the situation of the population in Afghanistan following the establishment of the current political regime, as well as their perception of the situation of the female population in Afghanistan and their level of receptiveness to the Afghan cultural situation. In this case, the value of CVR (Content Validity Report) proposed by Lawshe [

37] is 1 because a consensus with all the students participating in the study was reached [

37,

38]. The measurement scale used for each statement was a 5-point ordinal Likert scale. When the sixth answer option also appeared in the questions, it was an option by which the respondent declined his/her ignorance of the specifics of the question. The analysis stage of these questions involved grouping and coding the answers into general categories that would allow the processing and interpretation of the data. The results of the questionnaire were used both as statistical averages and as percentages of respondents.

The data were collected between January and February 2024, and the subjects were selected from all the years of study, irrespective of the degrees they were pursuing at Politehnica University of Timișoara, Romania. The responses of 420 subjects were recorded, the margin of error calculated by reference to the student population of this institution (13,500 students) [

39] being ±4.78%. The average age of the respondents was 22.1 years old. The gender distribution showed the following population distribution: 62.6% female and 37.4% male.

The completion of the questionnaire was performed online, voluntarily and anonymously, with the respondents able to give up any time before completion. No rewards were offered for obtaining answers, and no personal data were collected to allow the identification of the respondents. The average time required to fill in the questionnaire was 15 min, and the recorded response rate was approximately 50%.

4. Research Findings and Discussion

RO1. To determine the students’ levels of awareness concerning the situation of the population in Afghanistan following the establishment of the current political regime

In order to achieve this objective, the answers to a statement and two close-ended questions were considered. The statement used in the survey created the framework within which the students could describe the situation in Afghanistan in three words or in three sentences. The statement is based on Jung’s word association test [

40], and it puts the interlocutor in a difficult situation because it forces him/her to make use of his/her own memory and his/her own knowledge about the topic.

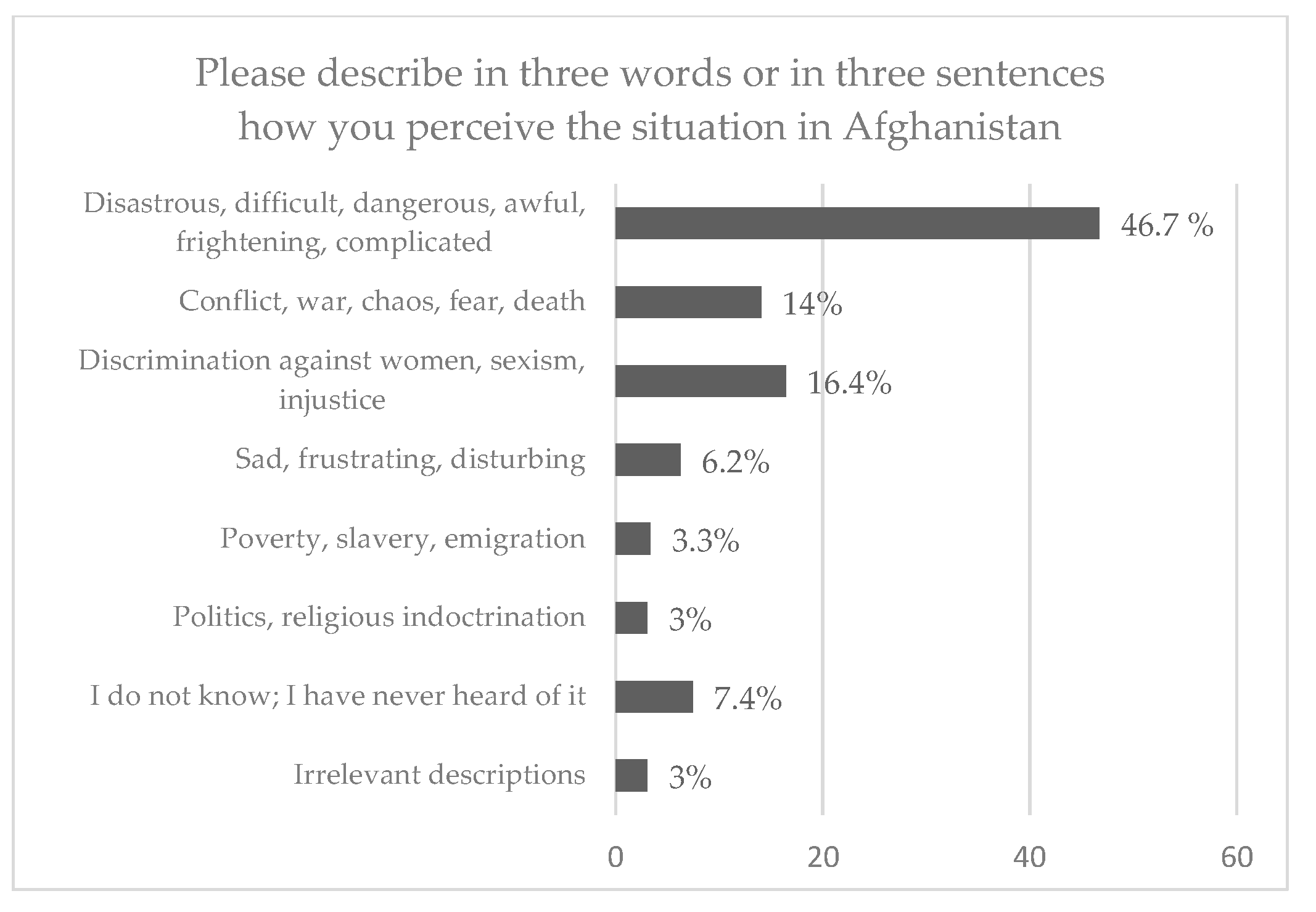

It can be seen that a very large number of respondents describe the situation as

disastrous, difficult, dangerous, awful, frightening and complicated (46.7%), while 14% of them see it as

conflict, war, chaos, fear, death. Moreover, 16.4% of the respondents talk about

discrimination against women, sexism and injustice (

Figure 3). Unfortunately, almost all wars have the effect of diminishing the rights of minorities and women [

41]. Other interviewees talk about the effects on people, the situation being

sad, frustrating, disturbing (6.2%) or even worse, bringing about

poverty, slavery, emigration (3.3%). All wars have also triggered waves of emigration [

42]. Another 3% of the interviewees mention

politics and

religious indoctrination. There is also a category of respondents who

do not know or

have not heard about this situation (7.4%) or who give

irrelevant responses (3%).

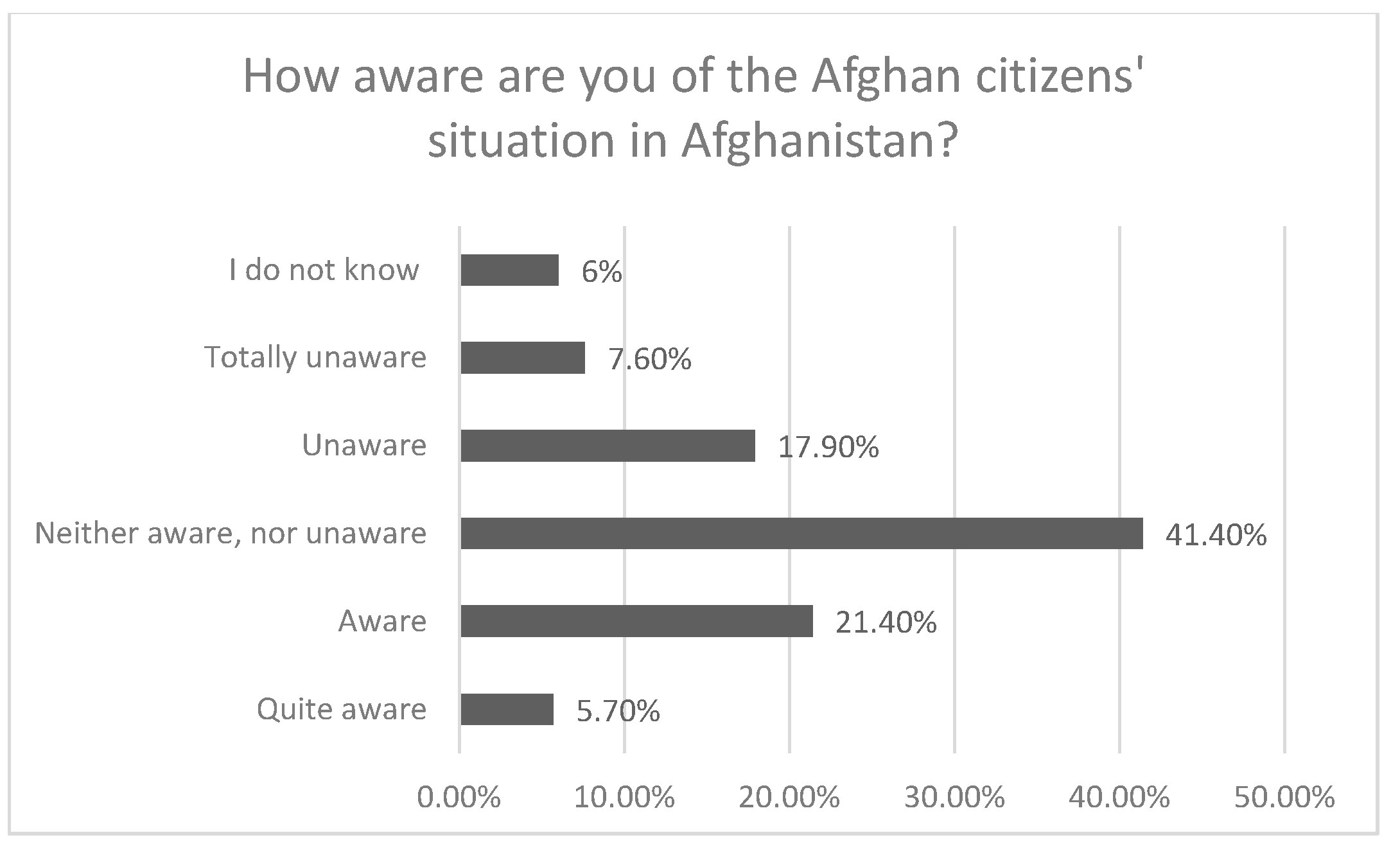

The next question deals with the respondents’ level of awareness of the situation in Afghanistan.

The surveyed Romanian students did not come into contact with Afghan citizens, except for very rare cases, since Afghanistan is a country far away from Romania, and only a few refugees were granted asylum in Romania, even after 2021 [

43]. More than half of the interviewees consider themselves aware, to some extent, of the situation in Afghanistan (

Figure 4). Therefore, 5.7% of the respondents are

quite aware, 21.4% of them are

aware and 41.4% are

neither aware, nor unaware. There are also participants who consider themselves

unaware (17.9%), who are

totally unaware (7.6%) and who

do not know (6%).

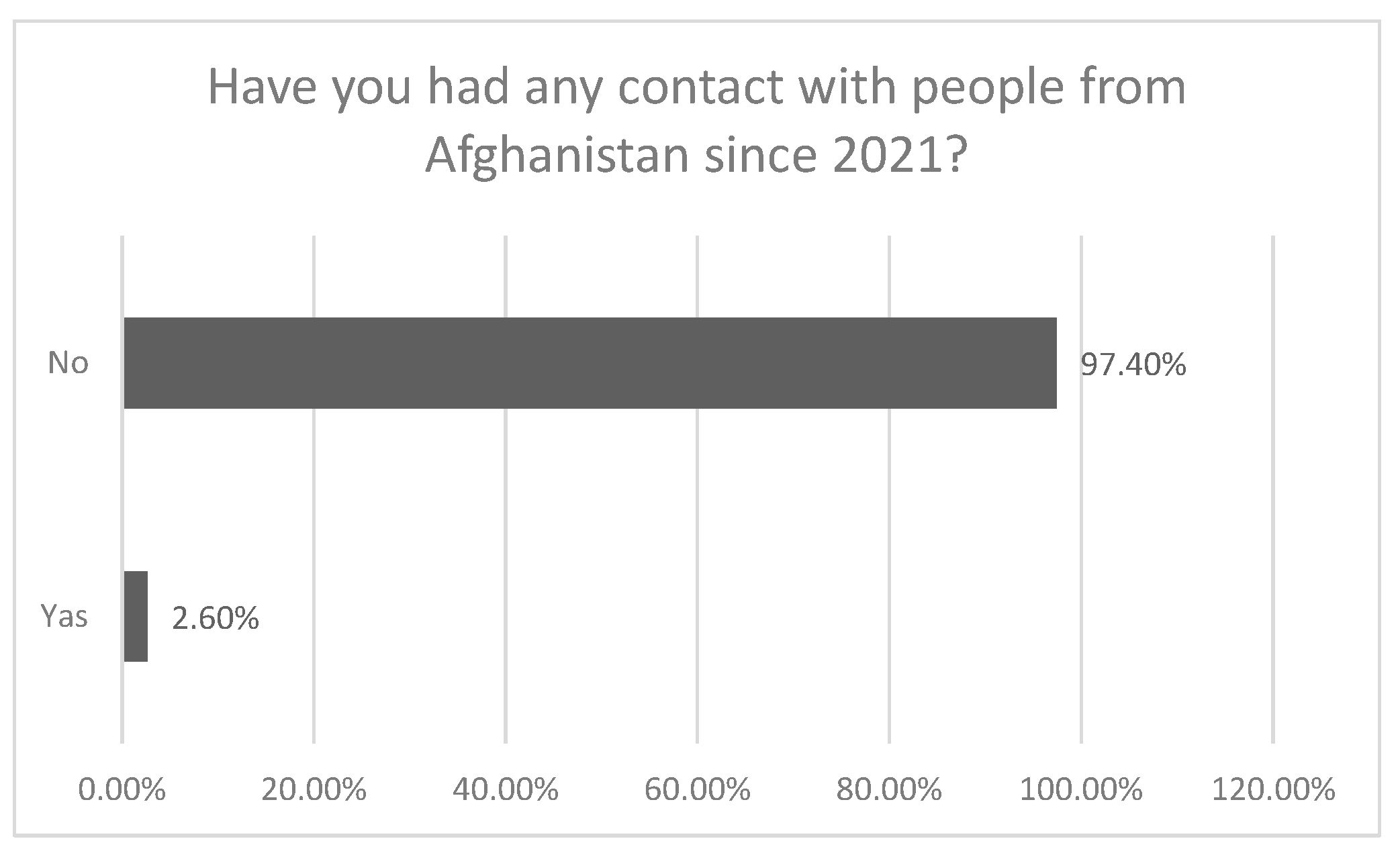

Related to the previous question, the subjects were also asked about any contacts or encounters with Afghan citizens since 2021 (

Figure 5).

As far as the relationship between the Romanians and the Afghans is concerned, the participants declared, in an overwhelming percentage of 97.4%, that they did not have contact with people from Afghanistan. As a result, the information they have about the situation under discussion is from the media, the Internet or from their own research. A small percentage of 2.6% of the participants answered positively (Yes) to this question, i.e., they have met people from this country under different circumstances. Yet, this study did not explore this aspect further in order to find out the contact methods they referred to.

RO2: To determine the students’ perceptions of the situation of the female population in Afghanistan following the establishment of the current political regime.

In order to meet this research objective, three close-ended questions were asked, their answers revealing the students’ perceptions of Afghan life, in particular that of the female population, under the Taliban regime. In what follows, the respondents’ perception of the Afghans’ life in general, with a stress on the Afghan women’s life, is presented.

Regarding the question related to Afghans’ life after the establishment of the current political regime, almost half of the respondents consider it worse, dividing it into

much worse—26.9% and

worse—21.2% (

Figure 6). These results were to be expected due to the fact that a less democratic political regime as the Taliban regime cannot be seen favourably by people from a European Union member country, particularly because of the cultural, political, religious and societal gap existing between Afghanistan and Romania [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20]. Moreover, 12.9% of the interviewees believed the lives of Afghanis were

the same, 7.1% believed that it was

better, 1.4% believed it was

much better and a high percentage (30.5) of the interviewees had

nothing to say about this matter. All in all, the results point to a lack of interest and information in 51.9% of the surveyed population regarding what happens in post-2021 Afghanistan, despite extensive coverage of the topic provided by the first four most trusted Romanian news brands, to mention but a few [

44,

45,

46,

47,

48].

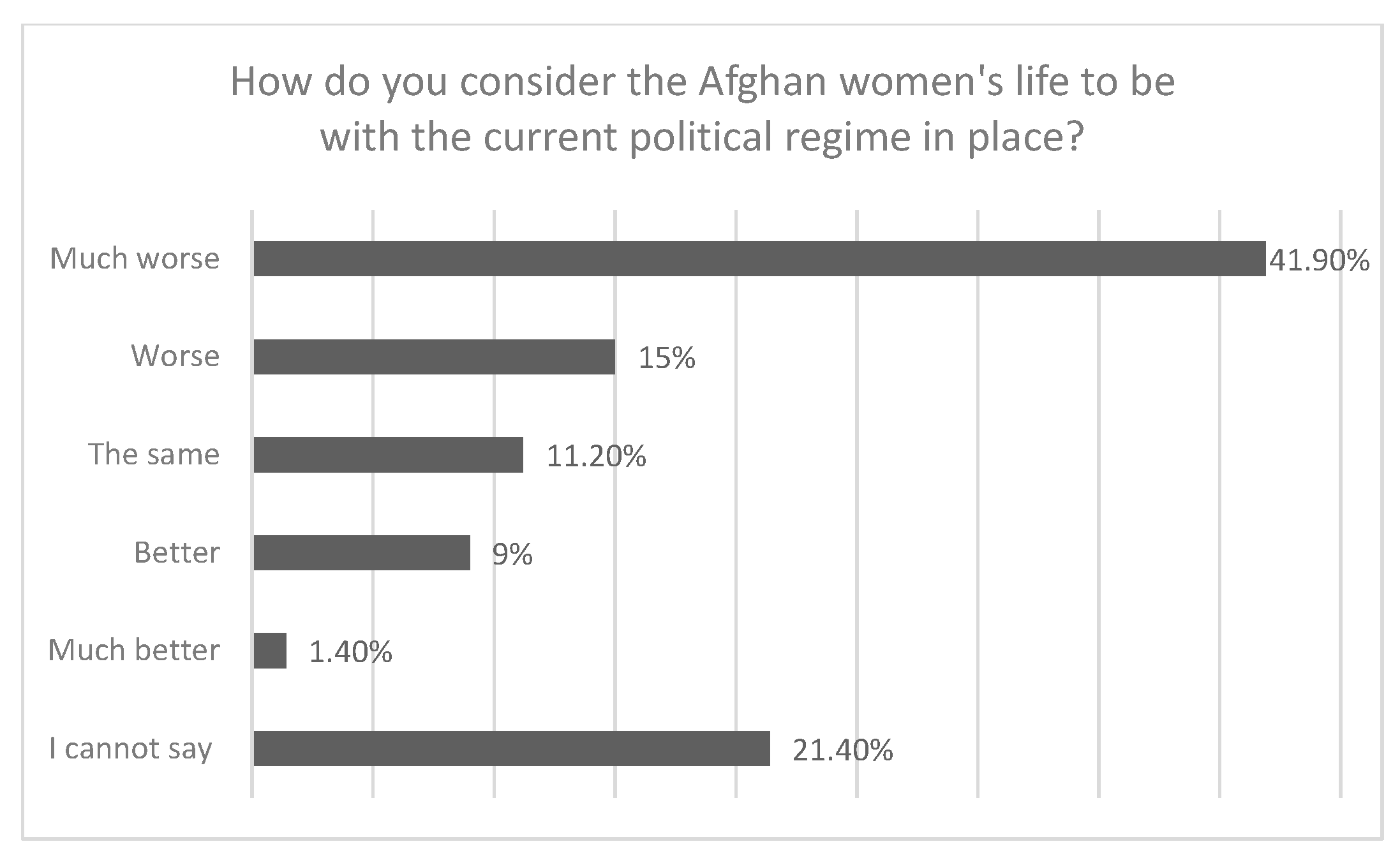

Regarding the perception of women’s lives in Afghanistan after the establishment of the current political regime, the percentages (

Figure 7) indicate that more than half of the respondents believe that women suffer greatly due to the new political changes. The data show that 41.9% of the participants believe that women do

much worse and 15% believe they do

worse. Moreover, 11.2% of the respondents point out that the situation is

the same. A category of approximately 10% are confident that women do

(much) better while the current political regime is in place (9% better and 1.4% much better). A significant ratio of 21.4% of subjects did not give an answer. In other words, most of the interviewees (56.9%) have an accurate image of the situation of Afghan women under the current political regime [

15,

16,

17,

21,

22,

23], whereas the rest of the surveyees are less informed.

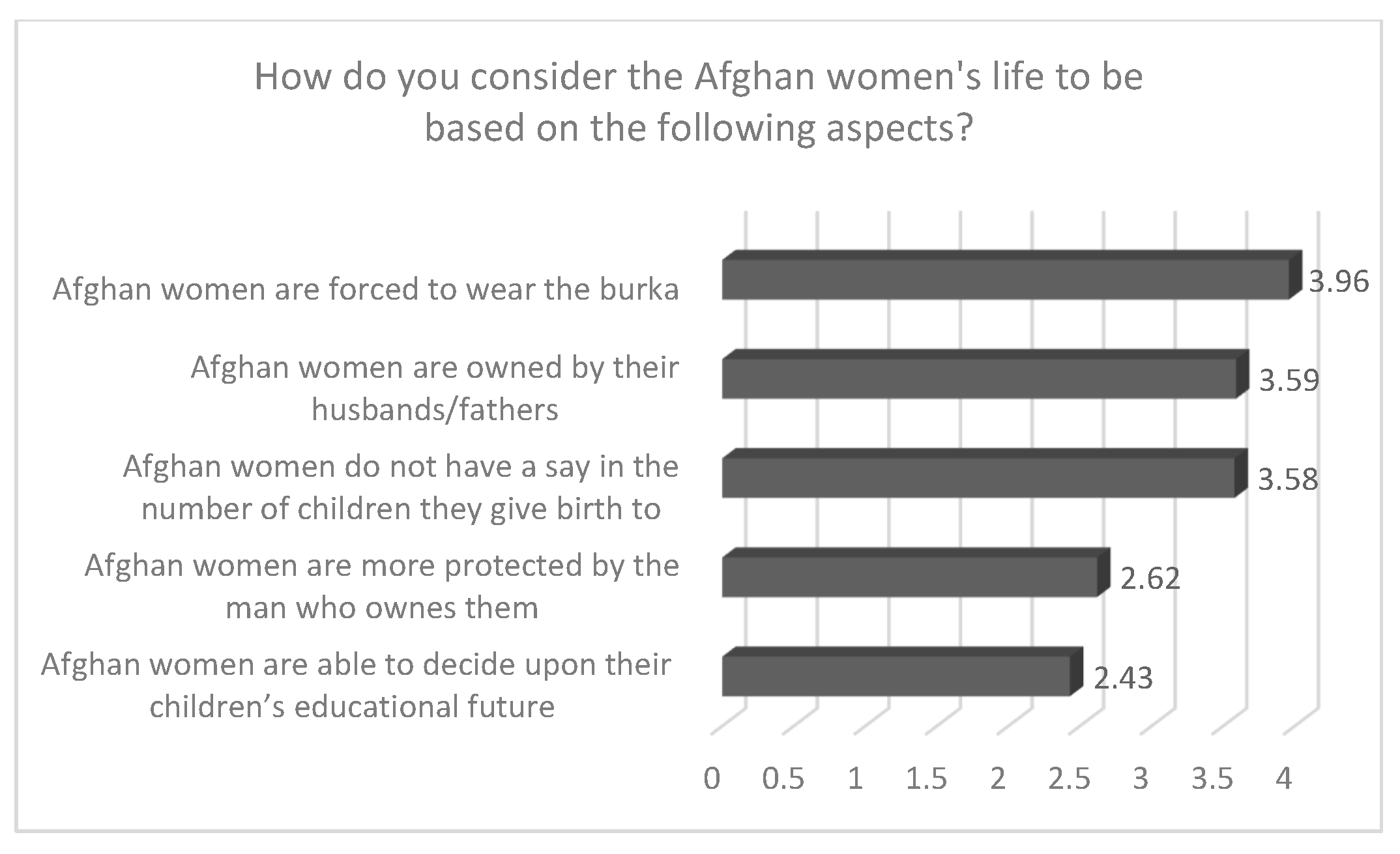

For this question, the respondents had to express their point of view about the life of Afghan women after the establishment of the current political regime. Knowing that it is a traditional and religious regime [

6,

16], the statements emphasised these particular aspects.

Figure 8 presents the answers on a measurement scale from 1 to 5, where 1 means

to a very small extent/not at all and 5 means

to a very large extent. Two categories of answers can be distinguished, i.e., the highest, as average statistics, relative to the middle of the scale, namely 3, and the lowest, relative to the same middle of the scale. In the first category, the following answers were recorded:

Afghan women are forced to wear the burka—3.96%;

Afghan women are owned by their husbands/fathers—3.59%;

Afghan women are able to decide upon their children’s educational future—3.58%. In other words, the most personal things in a woman’s life no longer belong to her. She can no longer have a public visual identity through her face. She has no rights since she is owned by her father or husband, and worse, she cannot decide on the matter of motherhood, i.e., on the number of children to give birth to. The second category of answers encompasses the following aspects, which scored averages below the middle of the scale, e.g.,

Afghan women are more protected by the man who owns them—2.62%;

Afghan women are able to decide upon their children’s educational future—2.43%. The percentage (2.62%) shows the respondents’ mistrust of the protection received by women from their men. Also, women are not able to decide much about their children’s educational future. Therefore, the respondents consider that women’s lives have not improved with the current political regime in Afghanistan.

RO3. To identify the students’ level of receptiveness to the Afghan cultural situation

The achievement of this objective relied on the answers to two open-ended and two close-ended questions.

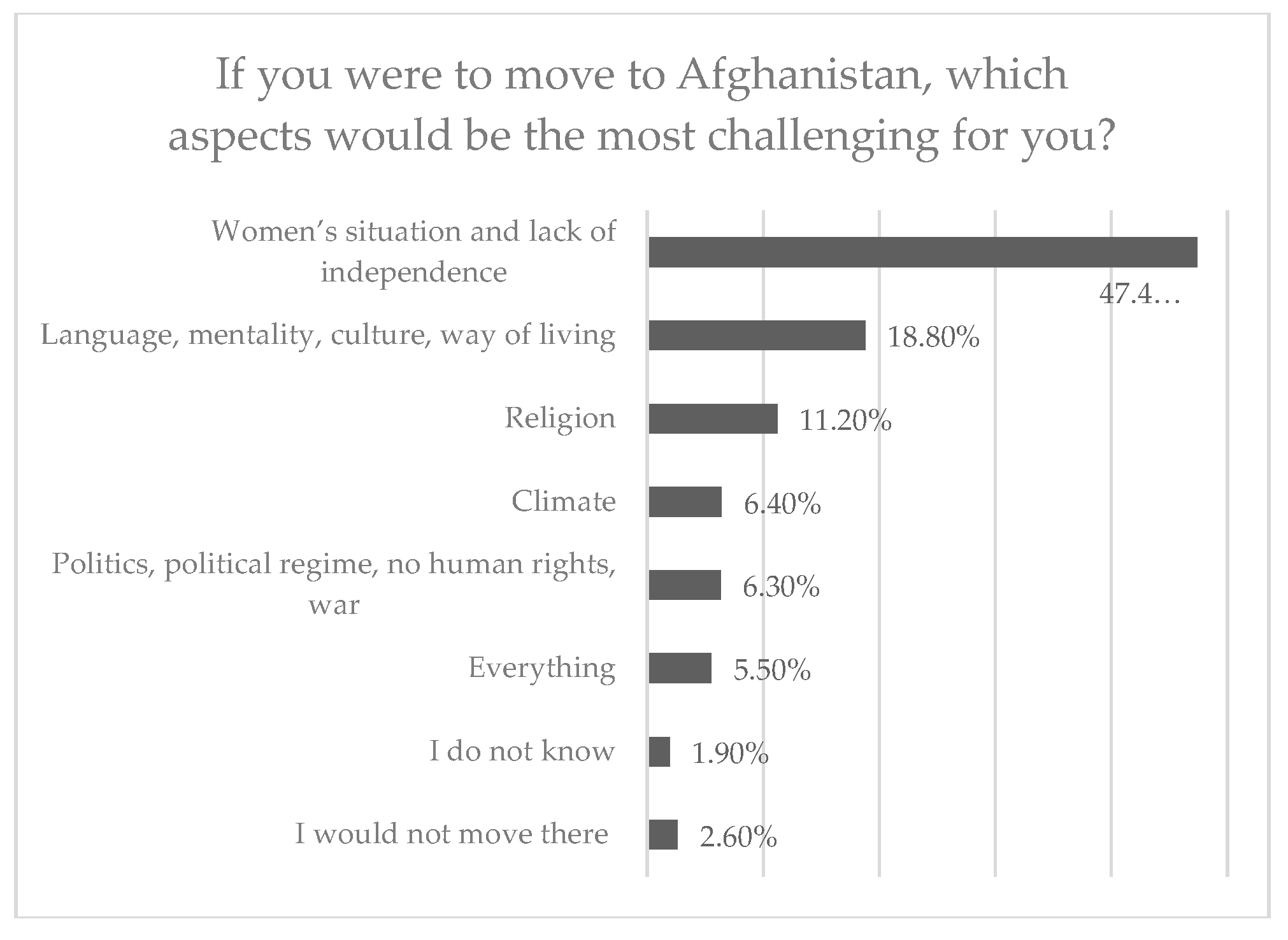

The first question regarding a hypothetical move to Afghanistan made the respondents think about facing such a difficult situation (

Figure 9). A very small percentage of them refused to perform this hypothetical exercise and answered

I would not move there—2.6% or

I do not know—1.9%. The other respondents dared to perform this exercise and imagine the challenges that would be in store for them. Therefore, the most challenging aspect for the interviewees is

women’s situation and lack of independence—47.4%. In what follows,

language, mentality, culture, way of living—18.8%;

religion—11.2%;

climate—6.4%;

politics, political regime, no human rights, war—6.3% rank second, third, fourth and fifth. On the extreme side, there are the participants believing that everything (5.5%) would be extremely challenging with such a move.

The second question mirrors the previous one in trying to find out the aspects that the respondents would find easier to cope with if they moved to Afghanistan. As seen in

Figure 10, 39.5% of the participants view

climate, environment, time zone as the easiest things to get accustomed to; 18.6% view

language, traditions, culture, religion, people as the easiest changes; and 5.7% consider

food as very adaptable. It is interesting to note that, even if in very low percentages,

male supremacy, women’s lack of independence scores 2.9%. There is also the category of those who believe that

everything would be difficult (2.7%) as well as the category of the respondents who

do not know and

cannot say (11.8%) or of the ones who

would not move there (18.8%).

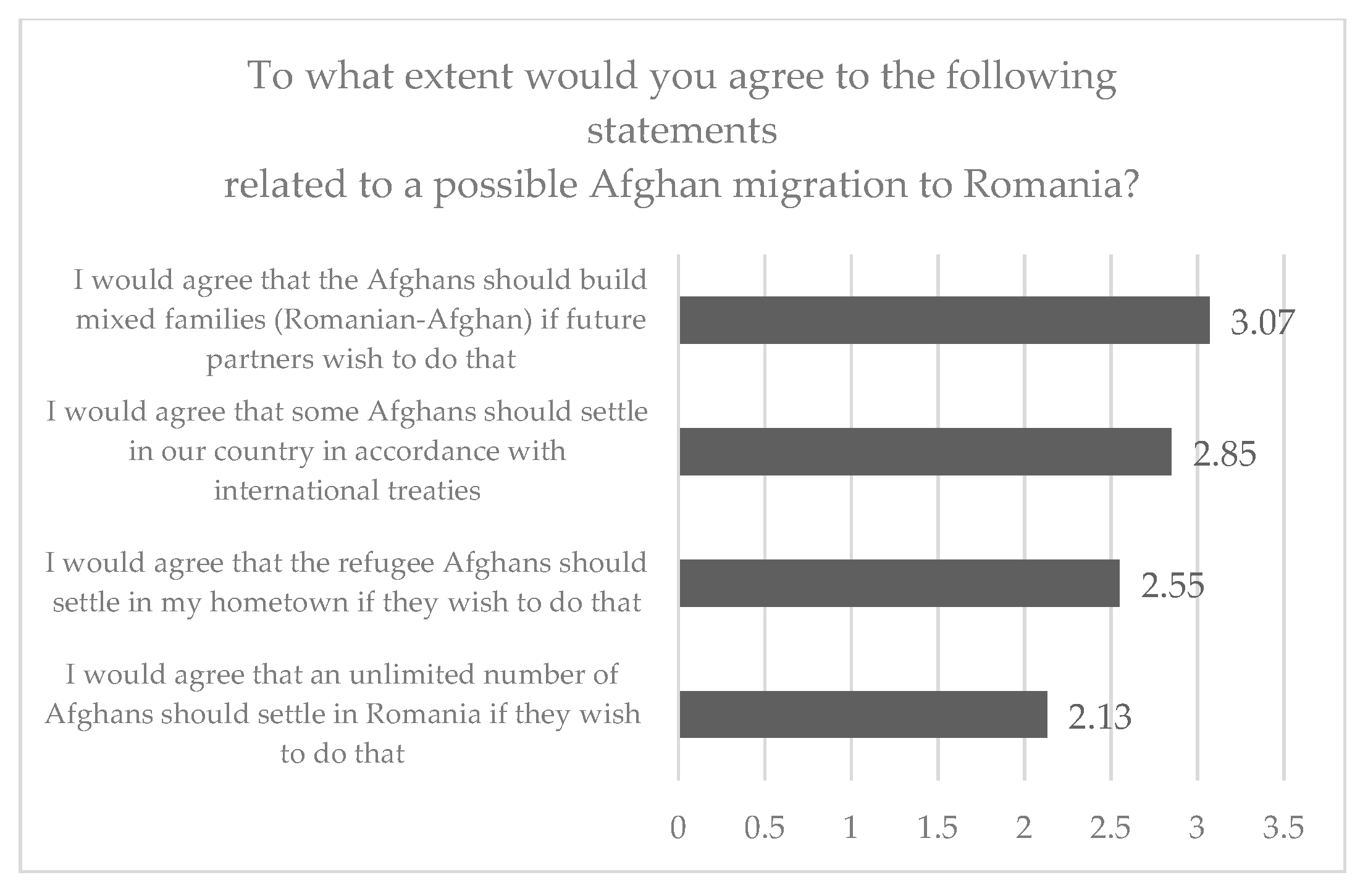

Inspired by the Bogardus social distance scale [

49,

50], in the third question, the respondents were asked about their degree of tolerance towards possible Afghan refugees (

Figure 11). On the same scale from 1 to 5, as in the previous question, answers were recorded above average and below average. Above the average of 3 on the scale, there is only one answer related to life and personal decisions, i.e.,

I would agree that the Afghans build mixed families (Romanian–Afghan) if future partners wish to do that (3.07%). Regarding the number of Afghans who could settle in Romania, different perceptions can be observed. Thus, the recorded answers are as follows:

I would agree that some Afghans settle in our country in accordance with international treaties (2.85%), and

I would agree that the refugee Afghans should settle in my hometown if they wish to do that (2.55%). In other words, although the averages are close (2.85% and 2.55%), they still would not agree to the same extent for Afghans to come and settle in Romania and in their hometown. Ranking last, as a statistical average, is the statement

I would agree that an unlimited number of Afghans should settle in Romania if they wish to do that (2.13%). This percentage could be explained by the ancestral fear that if other people coming from another culture and with other customs came in unlimited numbers to settle in your country, a part of your culture and existence would disappear [

51]. Furthermore, the Romanian collectivist culture with recent individualistic influences tends to protect the existing group by not easily accepting newcomers [

13,

33].

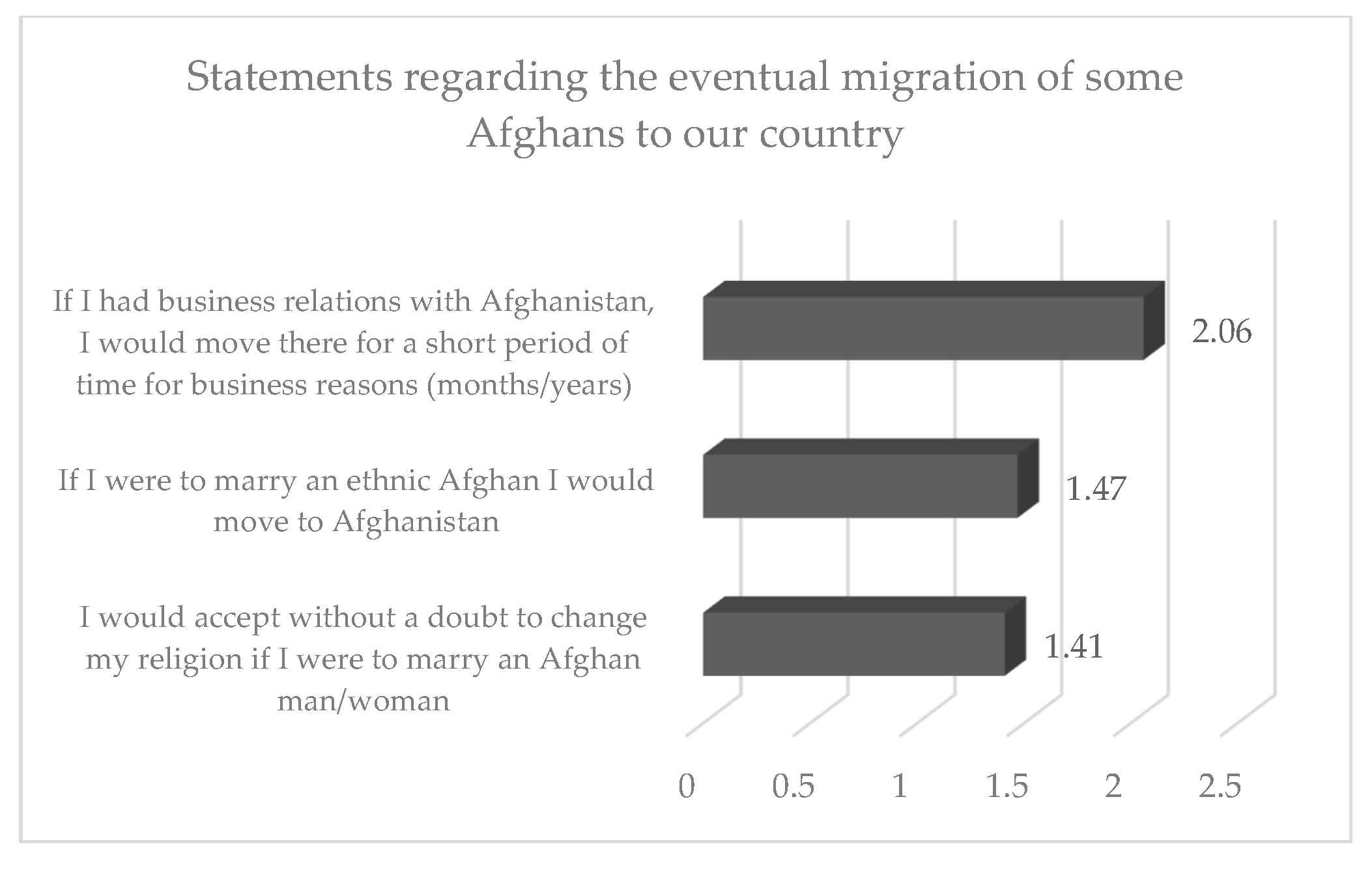

The fourth question is also related to hypothetical situations (

Figure 12). The answer ranking first is

If I had business relations with people from Afghanistan, I would move there for a short period of time for business reasons (months/years) (2.06%). Although the average of the responses is below the middle of the scale of 3, the respondents still consider the possibility of a move to Afghanistan if the business/job requires it. The other two hypothetical situations are less likely to change:

If I were to marry an Afghan man/woman, I would move to Afghanistan (1.47%),

I would accept without a doubt to change my religion if I were to marry an Afghan man/woman (1.41%). Moving to Afghanistan when the country is ravished by war, even by marriage or due to business reasons, would be unlikely. Therefore, the recorded answers portray a profile of the surveyees that reflects the national cultural traits revealed by other studies [

5,

8,

9,

11,

12,

13,

14,

16,

19,

33,

52], namely, Romanians avoid uncertainty and are rather long-term oriented, pragmatic, traditionalist, religious but not fundamentalist. Ultimately, Romanians safeguard the well-being of the group they belong to.

5. Conclusions

Living at a time when war and conflict are ravaging the world, some of the eternal issues that emerge in such periods are related to human rights, pointing out the vulnerability of the weak ones but also the weaknesses of the strong ones. In this context, Afghanistan is only one of the many regions in which violence has become the rule of law [

53], and human rights are constantly violated, especially those of women. Although non-interference in domestic affairs is stipulated by international law, one cannot turn a blind eye and refrain from drawing attention to the situations unfolding in various conflict zones across the globe. Considering all this, an online survey was carried out to highlight Romanian students’ perspectives on post-2021 Afghanistan, in general, and on Afghan women’s status, in particular, in a society wrenched by violence and injustice. Furthermore, the research aimed to show the respondents’ eagerness to resonate with the Afghan culture and situation, either in Romania or in Afghanistan. Therefore, almost half of the respondents described the situation in post-US-withdrawal Afghanistan as

disastrous, difficult, dangerous, terrible,

complicated where

conflict, war, chaos, fear, death are words that characterise everyday life and have that triggered waves of emigration. Only 2.6% of the respondents had direct contact with people from Afghanistan because of the geographical distance and the small number of Afghan migrants coming to Romania either to stay or in passing [

43]. Nevertheless, just over 63% of respondents declare themselves aware, to various degrees, of the situation in Afghanistan.

As for the way in which the respondents perceive Afghans’ lives with the current regime in place, almost half of them (49.1%) consider it worse or much worse, pointing once more to the cultural, religious, societal and political values that differ tremendously between the two countries [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

34,

35]. Moreover, 30.5% of them cannot give an answer due to a lack of information in spite of extensive media coverage of the post-2021 Afghan situation, both by national and foreign media companies operating in Romania [

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

54,

55].

As far as the situation of women in Afghanistan is concerned, 56.9% of the study participants believe that their lives are worse or much worse, thus revealing that they are indeed well acquainted with the critical situation of the Afghan female population [

15,

16,

17,

21,

22,

23]. Thus, the respondents think that women are forced to wear the burka, obey their men and do not have much say in terms of the number of children they carry, i.e., they will be one of the man’s assets. These answers once more stress the fact that women are the first to be affected by authoritarian political regimes that restrict the citizens’ rights and freedoms, and Afghanistan is no exception to that [

53].

In order to touch upon the respondents’ level of cultural receptiveness, some imaginative approaches were used through two open questions or through a series of statements related to the possible migration of Afghans to Romania. According to the interviewees, in case of a move to Afghanistan, the most difficult aspects to face would be those related to the situation of women and their rights, as well as those related to cultural elements such as language, mentality and religion. The climate, politics or consequences of the war were also taken into account. On the other hand, cultural differences are perceived by the respondents as more difficult to overcome and as barriers to cultural adjustment. The easiest aspects to accept by the survey participants would be the climate and the environment. There is also a percentage of almost 20% of them who flatly state that they would not move there. In what concerns the acceptance of Afghans in Romania, tolerance towards Romanian–Afghan mixed families could be noticed, but reservations regarding the acceptance of an unlimited number of Afghans in Romania could also be observed. All in all, the surveyees’ life choices illustrate the cultural traits of the Romanians, who are highly uncertainty avoidant, pragmatic, traditionalist, religious but not fundamentalist, rather long-term oriented and moderately collectivist and ready to protect the group(s) they are part of [

5,

8,

9,

11,

12,

13,

14,

16,

19,

33,

52].

As for the limitations of the study, the aforementioned sample size and the population from which this sample was drawn, namely, students pursuing a degree at the same university, Politehnica University of Timișoara (Romania), who generally come from the Western part of Romania. Another limitation is related to the limited experience of the recruited sample. In other words, the respondents are students who have usually learned about the approached topic from the mass media and have rarely met Afghan nationals in person. In compensation, the study should be continued on a sample extended to the entire territory of Romania and to other social environments, as different as possible from the university ones.

Such research certainly plays a pivotal role in helping the young population in democratic societies uphold their values and discover ways to advocate for equal opportunities and treatment for both women and men within their communities, although it might not improve women’s situation in Afghanistan significantly. While cultural identity profoundly influences human personality and shapes perceptions of different groups, misunderstandings about various cultures may arise due to inadequate or misleading information about groups outside one’s cultural area [

56]. Additionally, the surveyed Romanian students’ perceptions of the Afghan population may have been influenced by the media sources from which these young people are informed (see

Section 4: Research Findings and Discussion). Therefore, to foster intercultural understanding between Romania and Afghanistan, awareness and education should be prioritised by introducing educational programs and workshops to bridge knowledge gaps about Afghan culture, history and gender inequality. In other words, it becomes essential for those responsible for public education and information dissemination to extensively provide more accurate and thorough information. Also, cultural exchange programs should be promoted, focusing on shared values and addressing cultural differences. These efforts can build mutual understanding and solidarity between the two cultures. Furthermore, investing in digital inclusion and connectivity in Afghanistan can bridge the digital divide, empowering Afghan women and youth through online education, healthcare and economic opportunities while enabling virtual cultural exchanges with Romania.