Exploring AI Amid the Hype: A Critical Reflection Around the Applications and Implications of AI in Journalism

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Artificial Intelligence in Journalism: Friend or Foe?

3. AI and Journalism: A Reality Check

4. Journalism and AI: A Critical Political Economy Perspective

5. From AI Hype to Responsible AI

6. AI and the Normative Role of Journalism

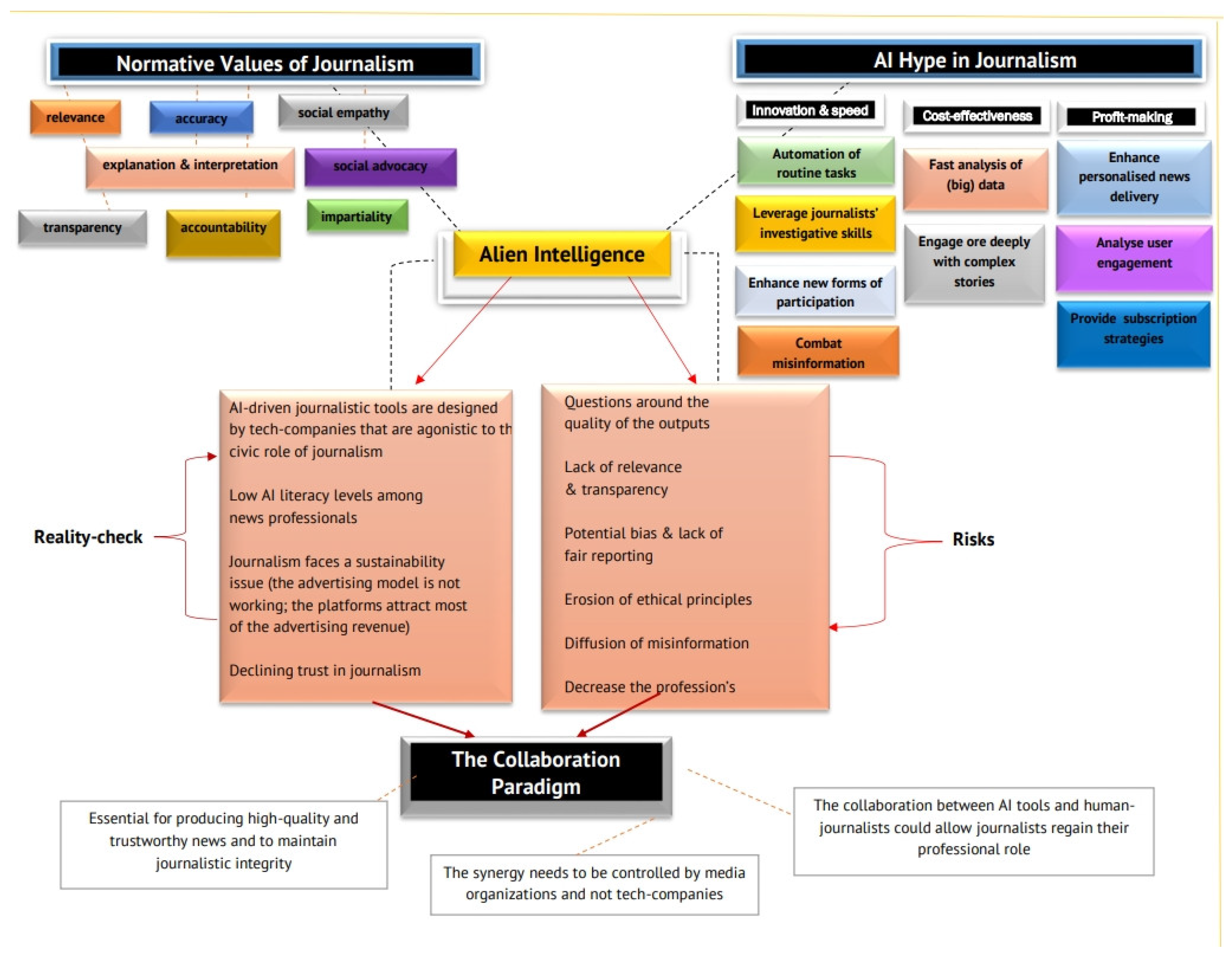

7. Alien Intelligence: Concept and Systemization

8. Artificial Intelligence and Journalism: The Road Ahead

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Yuval Noah Harari first coined the term “alien intelligence” in his book NEXUS: A Brief History of Information Networks from the Stone Age to AI (2024) to emphasize the idea that AI’s way of thinking is entirely different from humans. As AI learns and makes new decisions autonomously, it is no longer fully under human control. |

References

- Beckett, C. New Powers, New Responsibilities: A Global Survey of Journalism and Artificial Intelligence; The LSC: London, UK, 2019; Available online: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1utmAMCmd4rfJHrUfLLfSJ-clpFTjyef1/view (accessed on 20 October 2024).

- Sharadga, T.M.A.; Tahat, Z.; Safori, A.O. Journalists’ perceptions towards employing artificial intelligence techniques in Jordan TV’s newsrooms. Stud. Media Commun. 2022, 10, 239–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marconi, F. Newsmakers: Artificial Intelligence and the Future of Journalism; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Broussard, M.; Diakopoulos, N.; Guzman, A.L.; Abebe, R.; Dupagne, M.; Chuan, C.-H. Artificial intelligence and journalism. Journal. Mass Commun. Q. 2019, 96, 673–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helberger, N.; Marcel, V.D.; Judith, M.; Sander, V.; Steffen, E. Towards a normative perspective on journalistic AI: Embracing the messy reality of normative ideals. Digit. Journal. 2022, 10, 1605–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dörr, K. The Automation of Journalism; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Palomo, B.; Bahareh, H.; Pere, M. Horizon 2030 in journalism: A predictable future starring AI? In Total Journalism: Models, Techniques and Challenges; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 271–285. [Google Scholar]

- Vizoso, Á.; Vaz-Álvarez, M.; López-García, X. Fighting Deepfakes: Media and internet giants’ converging and diverging strategies against hi-tech misinformation. Media Commun. 2021, 9, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diakopoulos, N. Automating the News: How Algorithms Are Rewriting the Media; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Helberger, N.; Karppinen, K.; D’Acunto, L. Artificial intelligence and the public interest: Opportunities, risks, and tensions. Digit. Journal. 2019, 7, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Fridman, M.; Roy, K.; Fabrizio, P. How (not to) Run an AI Project in Investigative Journalism. Journal. Pract. 2023, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munoriyarwa, A. Have they got news for us? The decline of investigative reporting in Zimbabwe’s print media. Communication 2018, 44, 71–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diakopoulos, N. Algorithmic accountability: Journalistic investigation of computational power structures. Digit. Journal. 2015, 3, 398–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzman, A.L.; Lewis, S.C. Artificial intelligence and communication: A human–machine communication research agenda. New Media Soc. 2020, 22, 70–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Møller, L.A.; Skovsgaard, M.; de Vreese, C. Reinforce, readjust, reclaim: How artificial intelligence impacts journalism’s professional claim. Journalism 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deuze, M.; Beckett, C. Imagination, algorithms and news: Developing AI literacy for journalism. Digit. Journal. 2022, 10, 1913–1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donsbach, W. Journalism as the new knowledge profession and consequences for journalism education. Journal. Theory Pract. Crit. 2014, 15, 661–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, S.-J.; Fink, K. Keeping up with the technologies: Distressed journalistic labor in the pursuit of ‘shiny’ technologies. Journal. Stud. 2021, 22, 1987–2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittaker, J. Tech Giants, Artificial Intelligence, and the Future of Journalism; Routledge: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mellado, C.; Georgiou, M.; Nah, S. Advancing journalism and communication research: New concepts, theories, and pathways. Journal. Mass Commun. Q. 2020, 97, 333–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Örnebring, H. Technology and journalism-as-labour: Historical perspectives. Journalism 2010, 11, 57–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spyridou, P.; Danezis, C. Do algorithms do it better? Analysing occupational ideology in the age of computational journalism. Journal. Stud. 2024, 25, 1573–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posetti, J. Time to step away from the ‘bright, shiny things’? Towards a sustainable model of journalism innovation in an era of perpetual change. In RISJ Research Report; University of Oxford: Oxford, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Blumler, J.G. Foreword: The two-legged crisis of journalism. Journal. Stud. 2010, 11, 439–441. [Google Scholar]

- de Vreese, C.H.; Neijens, P. Measuring media exposure in a changing communications environment. Commun. Methods Meas. 2016, 10, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayyaz, Z.; Ebrahimian, M.; Nawara, D.; Ibrahim, A.; Kashef, R. Recommendation systems: Algorithms, challenges, metrics, and business opportunities. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 7748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.; Lewis, S. The one thing journalistic AI just might do for democracy. Digit. Journal. 2022, 10, 1627–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cave, S.; Dihal, K. Hopes and fears for intelligent machines in fiction and reality. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2019, 1, 74–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schudson, M. Why Democracies Need an Unlovable Press; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez-Caneda, B.; Vázquez-Herrero, J.; López-García, X. AI application in journalism: ChatGPT and the uses and risks of an emergent technology. Prof. Inf. 2023, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín-Sanchiz, C.R.; José María, V.-P.; Miguel, C.; Félix, A.-R. Mapping the use of artificial intelligence for the optimization of paywalls in the news media industry: How firms are taking advantage of machine learning and related technologies to increase reader revenue. In Future of Business and Finance Digital Disruption and Media Transformation; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 153–162. [Google Scholar]

- Salazar-García, I.-A. Robots and artificial intelligence. New challenges of journalism. Doxa Comun. 2018, 27, 295–315. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, S.; Norvig, P. Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach; Pearson: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Nardi, B.A. Activity theory and human-computer interaction. In Context and Consciousness: Activity Theory and Human-Computer Interaction; Nardi, B.A., Ed.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Simon, F.M. Uneasy bedfellows: AI in the news, platform companies and the issue of journalistic autonomy. Digit. Journal. 2022, 10, 1832–1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oremus, W. Why Robot. 2015. Available online: http://www.slate.com/articles/technology/future_tense/2015/02/automated_insights_ap_earnings_reports_robot_journalists_a_misnomer.single.html (accessed on 14 June 2024).

- Dörr, K. Mapping the field of algorithmic journalism. Digit. Journal. 2016, 4, 700–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, M. Automated journalism: A post man future for digital news? In The Routledge Companion to Digital Journalism Studies; Franklin, B., Eldridge, S., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Caswell, D. Structured journalism and the semantic units of news. Digit. Journal. 2019, 7, 1134–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, S.; Westlund, O. Actors, actants, audiences, and activities in cross-media news work. Digit. Journal. 2015, 3, 19–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejedor, S.; Vila, P. Exo Journalism: A Conceptual approach to a hybrid formula between journalism and artificial intelligence. Journal. Media 2021, 2, 830–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mooshammer, S. There are (almost) no robots in journalism: An attempt at a differentiated classification and terminology of automation in journalism on the base of the concept of distributed and gradualised action. Publizistik 2022, 67, 487–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danzon-Chambaud, S. A systematic review of automated journalism scholarship: Guidelines and suggestions for future research. Open Res. Eur. 2021, 1, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spyridou, L.P.; Veglis, A. Convergence and the changing labor of journalism: Towards the ‘super journalist’ paradigm. In Media Convergence Handbook-Vol. 1: Journalism, Broadcasting, and Social Media Aspects of Convergence; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 99–116. [Google Scholar]

- Quandt, T. Dark participation. Media Commun. 2018, 6, 36–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashidian, N.; Civeris, G.; Brown, P.; Bell, E.; Hartstone, A. Platforms and Publishers: The End of an Era. Tow Centre for Digital Journalism: New York, NY, USA, 2019. Available online: https://www.cjr.org/tow_center_reports/platforms-and-publishers-end-of-an-era.php/ (accessed on 22 October 2024).

- Coddington, M. Clarifying journalism’s quantitative turn. Digit. Journal. 2015, 3, 331–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, J.T.; Turner, F. Accountability Through Algorithm: Developing the Field of Computational Journalism. Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences Summer Workshop. 2009. Available online: https://web.stanford.edu/~fturner/Hamilton%20Turner%20Acc%20by%20Alg%20Final.pdf (accessed on 11 June 2024).

- Noain-Sánchez, A. Addressing the impact of artificial intelligence on journalism: The perception of experts, journalists and academics. Commun. Soc. 2022, 35, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amponsah, P.N.; Atianashie, M.A. Navigating the new frontier: A comprehensive review of AI in journalism. Adv. Journal. Commun. 2024, 12, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friday, J.P.; Soroaye, M.P. The Rise of AI Journalism: How Algorithms Are Shaping News Content. Preprint 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siu, A. Through Understanding Bots, Journalists Can more Effectively Fight Disinformation. 2018. Available online: https://ijnet.org/en/story/through-understanding-bots-journalists-can-more-effectively-fight-disinformation (accessed on 7 June 2024).

- Jamil, S. Artificial intelligence and journalistic practice: The crossroads of obstacles and opportunities for the Pakistani journalists. Journal. Pract. 2020, 15, 1400–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manfredi Sánchez, J.L.; Ufarte-Ruiz, M.J. Artificial intelligence and journalism: A tool to fight disinformation. Rev. CIDOB D’afers Int. 2020, 124, 49–72. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y. Artificial intelligence in educational leadership: A symbiotic role of human-artificial intelligence decision-making. J. Educ. Adm. 2021, 59, 256–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ufarte Ruiz, M.J.; Calvo-Rubio, L.M.; Murcia-Verdú, F.J. Los desafíos éticos del periodismo en la era de la inteligencia artificial. Estud. Sobre Mensaje Periodís. 2021, 27, 673–684. [Google Scholar]

- Castillo-Campos, M.; Varona-Aramburu, D.; Becerra-Alonso, D. Artificial intelligence tools and bias in journalism-related content generation: Comparison between Chat GPT-3.5, GPT-4 and Bing. Tripodos 2024, 24, 99–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavtaradze, L. Challenges of Automating Fact-Checking: A Technographic Case Study. Emerg. Media 2024, 2, 236–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, S.C.; Guzman, A.L.; Schmidt, T.R. Automation, journalism, and human–machine communication: Rethinking roles and relationships of humans and machines in news. Digit. Journal. 2019, 7, 409–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckett, C.; Yaseen, M. Generating change. A global survey of what news organisations are doing with AI. In LSE Report; LSE: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Rawte, V.; Sheth, A.; Das, A. A survey of hallucination in large foundation models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2309.05922. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z. Sociological perspectives on artificial intelligence: A typological reading. Sociol. Compass. 2021, 15, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almakaty, S.S. The impact of artificial intelligence on global journalism industry: An analytical study. Rev. Commun. Res. 2024, 12, 115–133. [Google Scholar]

- Salamon, E. Negotiating Technological Change: How media unions navigate artificial intelligence in journalism. Journal. Commun. Monogr. 2024, 26, 159–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, F. Artificial Intelligence in the News: How AI Retools, Rationalizes, and Reshapes Journalism and the Public Arena. Available online: https://www.cjr.org/tow_center_reports/artificial-intelligence-in-the-news.php (accessed on 14 October 2024).

- Wahl-Jorgensen, K.A. Manifesto of failure for digital journalism. In Remaking the News: Essays on the Future of Journalism Scholarship in the Digital Age; Boczkowski, P.J., Anderson, C.W., Eds.; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Poell, T.; Nieborg, D.B.; Duffy, B.E. Spaces of negotiation: Analyzing platform power in the news industry. Digit. Journal. 2022, 11, 1391–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosco, V. The Political economy of communication: A living tradition. Media Asia 2009, 36, 146–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golding, P.; Murdock, G. The political economy of contemporary journalism and the crisis of public knowledge. In The Routledge Companion to News and Journalism; Stuart, A., Ed.; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Hardy, J. Political Economy of News. In The International Encyclopedia of Journalism Studies; Meier, K., Vos, T.P., Hanusch, F., Dimitrakopoulou, D., Geertsema-Sligh, M., Sehl, A., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gitlin, T. Journalism’s Many Crises Open Democracy. 25 May 2009. Available online: https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/a-surfeit-of-crises-circulation-revenue-attention-authority-and-deference/ (accessed on 5 October 2024).

- Anderson, C.W.; Bell, E.; Shirky, C. Post-Industrial Journalism: Adapting to the Present; Tow Center for Digital Journalism: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Goldhaber, M.H. The Attention Economy and the Net. First Monday 1997, 2, 4–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nixon, B. Recovering audience labor from audience commodity theory: Advertising as capitalizing on the work of signification. In Explorations in Critical Studies of Advertising; Hamilton, J.F., Bodle, R., Korin, E., Eds.; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Smyrnaios, N.; Rebillard, F. How infomediation platforms took over the news: A longitudinal perspective. Polit. Econ. Commun. 2019, 7, 30–50. [Google Scholar]

- Rashidian, N.; Brown, P.; Hansen, E.; Bell, E.; Albright, J.; Hartsone, A. Friend and Foe: The Platform Press at the Heart of Journalism. Columbia Journalism Review. 14 June 2018. Available online: https://www.cjr.org/tow_center_reports/the-platform-press-at-the-heart-of-journalism.php (accessed on 25 October 2024).

- Cherubini, F.; Rasmus, K.N. Editorial Analytics: How News Media are Developing and Using Audience Data and Metrics; Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Tandoc, E., Jr.; Vos, T. The journalist is marketing the news. Journal. Pract. 2016, 10, 950–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petre, C. All the News That’s Fit to Click: How Metrics Are Transforming the Work of Journalists; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Sjøvaag, H. The business of news in the AI economy. AI Mag. 2024, 45, 169–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raviola, E. Exploring organizational framings. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2012, 15, 932–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakke, N.A.; Barland, J. Disruptive innovations and paradigm shifts in journalism as a business: From advertisers first to readers first and traditional operational models to the AI factory. High. Educ. Future 2022, 12, 200–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleis, N.R.; Ganter, S.A. Dealing with digital intermediaries: A case study of the relations between publishers and platforms. New Media Soc. 2018, 20, 1600–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vatikiotis, P.; Maniou, T.A.; Spyridou, P. Towards the individuated journalistic worker in pandemic times: Reflections from Greece and Cyprus. Journalism 2024, 25, 2320–2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rick, J.; Hanitzsch, T. Journalists’ perceptions of precarity: Toward a theoretical model. Journal. Stud. 2024, 25, 199–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, D. Impact of artificial intelligence on journalism: A comprehensive review of AI in journalism. J. Commun. Manag. 2024, 3, 150–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Stefano, V. Negotiating the algorithm: Automation, artificial intelligence and labour protection. Comp. Labor Law Policy J. 2019, 41, 15–46. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, X.L.; Zhu, B.K.; Ma, C. Industrial robot use and manufacturing employment: Evidence from China. Stat. Res. 2020, 37, 74–87. [Google Scholar]

- Makwambeni, B.; Matsilele, T.; Msimanga, M.J. Through the lenses of the sociology of news production: An assessment of social media applications and changing newsroom cultures in Lesotho. J. Asian Afr. Stud. 2023, 2023, 00219096231179661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswal, S.-K.; Gouda, N.-K. Artificial intelligence in journalism: A boon or bane? In Optimization in Machine Learning and Applications; Kulkarni, A., Satapathy, S., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- de Lima-Santos, M.F.; Ceron, W. Artificial intelligence in news media: Current perceptions and future outlook. Journal. Media 2021, 3, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinrich, A.; Spyridou, P.L. Digital Sourcing. In The Routledge Companion to Digital Journalism Studies; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2024; pp. 299–308. [Google Scholar]

- Kuai, J.; Ferrer-Conill, R.; Karlsson, M. AI ≥ journalism: How the Chinese copyright law protects tech giants’ AI innovations and disrupts the journalistic institution. Digit. Journal. 2022, 10, 1893–1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, C.E. Media, Markets, and Democracy; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, R.K. The one thing journalism just might do for democracy. Journal. Stud. 2017, 18, 1251–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dafoe, A. AI Governance: A Research Agenda; Centre for the Governance of AI, Future of Humanity Institute, University of Oxford: Oxford, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Diago, G. Perspectives to address artificial intelligence in journalism teaching. A review of research and teaching experiences. Rev. Lat. Comun. Soc. 2022, 80, 29–45. [Google Scholar]

- Zamith, R.; Braun, J.A. Technology and journalism. Int. Encycl. Journal. Stud. 2019, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Fenton, N. Post-Democracy, press, politics and power. Political Q. 2016, 87, 81–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, R. Helpfulness as journalism’s normative anchor. Journal. Stud. 2019, 20, 364–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carey, J. A Critical Reader; U of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Hanitzsch, T.; Vos, T. Journalistic roles and the struggle over institutional identity: The discursive constitution of journalism. Commun. Theory 2017, 27, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lischka, J.A. Fluid institutional logics in digital journalism. J. Media Bus. Stud. 2020, 17, 113–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christians, C.G.; Glasser, T.; McQuail, D.; Nordenstreng, K.; White, R.A. Normative Theories of the Media: Journalism in Democratic Societies; University of Illinois Press: Champaign, IL, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Blumler, J.-G.; Cushion, S. Normative perspectives on journalism studies: Stock-taking and future directions. Journalism 2014, 15, 259–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jungherr, A. Artificial intelligence and democracy: A conceptual framework. Soc. Media + Soc. 2023, 9, 20563051231186353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges-Rey, E. Data journalism in Latin America: Community, development and contestation. In Data Journalism in the Global South; Bruce, M., Saba, B., Eddy, B.-R., Eds.; Palgrave: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- McChesney, R.W. The Political Economy of Media: Enduring Issues, Emerging Dilemmas; NYU Press: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson, M. Automating judgment? Algorithmic judgment, news knowledge, and journalistic professionalism. New Media Soc. 2018, 20, 1755–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelizer, B. Why journalism is about more than digital technology. Digit. Journal. 2019, 7, 343–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harari, Y.N. Nexus: A Brief History of Information Networks from the Stone Age to AI; Random House Publishing Group: New York, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs, C. Ibn Khaldun and the political economy of communication in the age of digital capitalism. Crit. Sociol. 2024, 50, 727–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, M.; Meritxell, R.-S.; Jon, M.K.; George, K. Artificial Intelligence: Practice and Implications for Journalism; Tow Center for Digital Journalism and the Brown Institute for Media Innovation: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kuai, J. Unravelling copyright dilemma of AI-generated news and its implications for the institution of journalism: The cases of US, EU, and China. New Media Soc. 2024, 26, 5150–5168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porlezza, C. Promoting responsible AI: A European perspective on the governance of artificial intelligence in media and journalism. Communications 2023, 48, 370–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graefe, A. Guide to Automated Journalism. 2016. Available online: https://www.cjr.org/tow_center_reports/guide_to_automated_journalism.php (accessed on 10 June 2024).

- Lopez-Ortega, O. Computer-assisted creativity: Emulation of cognitive processes on a multi-agent system. Expert Syst. Appl. 2013, 40, 3459–3470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marconi, F.; Seigman, A. The Future of Augmented Journalism: A Guide for Newsrooms in the Age of Smart Machines. Report; Associated Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017; Available online: https://jeanetteabrahamsen.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/ap_insights_the_future_of_augmented_journalism.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2024).

- Moran, R.E.; Shaikh, S.J. Robots in the news and newsrooms: Unpacking meta-journalistic discourse on the use of artificial intelligence in journalism. Digit. Journal. 2022, 10, 1756–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spyridou, P.; Djouvas, C.; Milioni, D. Modeling and validating a news recommender algorithm in a mainstream medium-sized news organization: An experimental approach. Future Internet 2022, 14, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, M.S.; Borges-Rey, E. Re-opening the black box of code in the era of digital technology. Digit. Journal. 2024, 12, 1068–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Spyridou, P.; Ioannou, M. Exploring AI Amid the Hype: A Critical Reflection Around the Applications and Implications of AI in Journalism. Societies 2025, 15, 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15020023

Spyridou P, Ioannou M. Exploring AI Amid the Hype: A Critical Reflection Around the Applications and Implications of AI in Journalism. Societies. 2025; 15(2):23. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15020023

Chicago/Turabian StyleSpyridou, Paschalia (Lia), and Maria Ioannou. 2025. "Exploring AI Amid the Hype: A Critical Reflection Around the Applications and Implications of AI in Journalism" Societies 15, no. 2: 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15020023

APA StyleSpyridou, P., & Ioannou, M. (2025). Exploring AI Amid the Hype: A Critical Reflection Around the Applications and Implications of AI in Journalism. Societies, 15(2), 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15020023