1. Introduction

Italy is a significant migrant destination for South Asians in the recent two decades, mainly from Pakistan, India, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, and Nepal [

1,

2]. Recent Asian migration to Europe reviews point to the fact that South and Southeast Asian migration has increased significantly over the past ten years due to economic opportunities, labour shortage among the hosts, and wider demographic pressures [

3]. These tendencies emphasize the increased place of Italy in broader European migration frames and offer a valuable background to the study of the labour market experience of South Asian migrants. These communities are now at the heart of agriculture, domestic labour, care work, construction, and logistics, the majority of which have high precarity, informality, and minimal legal protections [

4]. Despite their economic contributions, South Asian migrants continue to be affected by systemic constraints in settling into the labour market, including restrictions on legal status, language barriers, lack of credential recognition, and exploitation through non-formal employment contracts [

5]. There has also been evidence of high levels of occupational segregation and under-employment among these groups [

6]. However, recent evidence shows that the majority of migrants assess very high levels of job satisfaction, even under such tough conditions—a so-called “migrant satisfaction paradox” [

7]. This inconsistency raises important theoretical questions about how migrants form their subjective evaluations of their work in labour market despite structural disadvantages; this area of work is connected to segmented labour market theory, relative expectations, and migrants’ role in social networks. While growing attention is devoted to migrant job satisfaction, several research gaps still exist. Perhaps above all, satisfaction is generally analyzed at aggregate levels and not disaggregated by nationality or legal status, typically without exploring how different dimensions of satisfaction interact to shape general perceptions [

8,

9]. Furthermore, little empirical research exists on how these personal experiences correlate with structural results such as national identity, citizenship status, or gender positioning within the labour market. Previously available literature rarely incorporated theoretical frameworks like dual/segmented labour market theory, human capital challenges, or intersectionality in terms of explaining why specific migrant groups experience differentiated levels of job satisfactions. The South Asian community in Italy is particularly under-researched in this field despite being one of Italy’s fastest-growing and most structurally marginalized migrant groups [

10,

11]. In addition, there is limited validation of the measurement of job satisfaction itself in migration studies, even though the multidimensionality of satisfaction and the importance of contextual influences is highlighted by the internationally established scales. The purpose of this research is to fill these gaps by exploring the connection between multidimensional job satisfaction among South Asian migrants and the primary indicators of structural differentiation. The research, in particular, examines how nationality, legal status (Italian citizenship), and gender relate to satisfaction, in order to better understand the subjective labour evaluations reflected in the broader process of labour market stratification and the integration of migrants in the context of stratified labour markets.

In order to achieve these aims, this research study employs a three-step quantitative approach. First, frequency and percentage distributions of job satisfaction variables are computed in order to study variation across national groups. Descriptive analysis provides a preliminary sense of how different migrant communities think about key employment features. Second, Multiple Correspondence Analysis (MCA) is used to extract latent factors from multidimensional satisfaction data, and hierarchical clustering is then used to identify unique satisfaction profiles among migrants. Such clusters are subsequently profiled in order to reveal the typologies of the labour market experience, from low satisfaction and marginalization to high satisfaction and integration. Finally, multinomial logistic regression is used to investigate whether dimensions of satisfaction are effective predictors of migrants’ nationality, Italian citizenship status, and gender. This approach also helps to connect the descriptive patterns with explanatory models and enables the assessment of how subjective evaluations of jobs correspond to the structural inequalities of the market. This shift transforms analysis from an exploratory to an explanatory endeavour, revealing the extent to which subjective judgments of work correlate with structural identity markers. Together, these analyses create an integrated framework to link migrant job satisfaction to labour market segmentation and socio-legal positioning, thereby contributing to wider debates on migrant integration into the labour market in contemporary Italy.

2. Literature Review

Asian migration to Europe is not a recent phenomenon, and South Asian countries such as India, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka have been significant contributors to these flows. Colonial links initially drove South Asian migration to Europe, and the United Kingdom was one of the primary destinations. However, over time, focus has shifted to other European countries, like Italy, due to changing economic and political circumstances [

12,

13]. The migratory streams have been characterized by a mix of skilled and unskilled labour, with recent years witnessing an increased intensity of high-skilled migration [

14]. In Italy, migrants from South Asia, particularly Indians, have settled mainly in the north, where they are employed in agriculture, IT, and engineering. The Italian government has made efforts to facilitate the integration of these migrants, as they have made enormous contributions to the economy [

13]. However, the migratory context has become more complex due to the 2015–2016 migration crisis, leading to more closed-off policies and an even greater emphasis on skilled immigration [

12]. These developments highlight larger trends in Europe towards selective migration regimes privileging high-skilled workers while also maintaining entry restriction and mobility for migrants with low skills [

15]. Migrant worker integration in Italy has dramatically shifted in recent decades, with South Asian migrant workers from India, Bangladesh, Nepal, and Sri Lanka comprising a rising proportion of the workforce [

1,

2]. These groups are often employed in low-skilled, informal, and precarious jobs. Some of these include agriculture, industry, and domestic work [

16]. Migrants’ concentration in low-wage segments is generally explained by segmented labour market theory, which argues that migrants are disproportionately channelled into an insecure sector named the “secondary sector” with limited upward mobility [

17]. While abundant literature has documented objective inequalities, including underemployment, contractual insecurity, and discrimination, migrants’ subjective work experiences, including job satisfaction and perceived job security, have received considerably less attention. Some studies highlight pervasive mismatches between education and occupations among non-EU migrants in Europe by examining skill underutilization and overqualification [

18]. Existing Italian research challenges this gap. Piccitto et al., (2025) [

19], for example, find that migrants in Italy are more likely to be satisfied with their work than natives, despite structural disadvantages, a phenomenon they describe as the job-satisfaction paradox. The paradox suggests that migrants may reinterpret expectations or derive satisfaction from non-material benefits such as stability or social support. Similar studies comparing the UK, Spain, and Germany found that migrants often report unexpectedly higher satisfaction levels, which are influenced by the adaptation process, limited reference group, and lowered expectations [

20,

21,

22]. Sociological reviews also note that work satisfaction among immigrants results from an interplay between work factors (e.g., autonomy, pay, and work environment) and non-work factors (e.g., social integration and cultural congruence) [

23]. However, the existing literature rarely disaggregates satisfaction by nationality or legal status, or limits its understanding of how structural inequalities shape subjective evaluations. It is also argued by studies grounded in intersectionality that together, nationality, legal status, and gender produce stratified positions of the labour market, and these directly influence job satisfaction [

24,

25].

The subjective well-being of migrants is one of the most important indicators of their integration and satisfaction level. Demographic and human capital variables such as age, education, and language proficiency have been proven to be significant determinants of life satisfaction among migrants in Italy [

26,

27]. More than these structural and integration-type determinants, there are larger gendered migration studies that indicate that the mobility of women is informed by specific labour restrictions and empowerment routes. Also, those that concentrate on internal migration within South Asia, like the study by Ram & Nizamani [

28], emphasize the feminization of migration in response to gendered labour-market inequalities, a dimension that explains why gender is a necessary aspect in examining the work experiences and satisfaction of migrants. Transnationalism and belonging are other key factors accountable for migrants’ life satisfaction. Migrants with strong links to their homelands and a sense of belonging to the host nation also tend to report greater well-being [

27]. Social capital theory highlights that ethnic or cross-ethnic networks both play a key role in shaping opportunities for work, expectations, and subjective evaluations [

29,

30]. Another important dimension is labour market motivation and migration pathways. Recent work by Impicciatore & Molinari [

2] shows how migrants’ migration motivations—economic, family, or humanitarian—shape initial labour market trajectories and the quality of employment, and thereby affect satisfaction and more medium-term integration. Their work shows that economic migrants migrate quickly into employment, albeit of low quality, which can create both satisfaction (at having an income) and dissatisfaction (due to mismatch). In addition, Indian migrants in Italy reveal fragmented integration: some attain labour market inclusion through transnational networks, while others are excluded by irregular status, skill under-recognition, or unfavourable institutional contexts [

1]. These further align with human capital theory [

31] and insider-outsider theory that emphasizes how migrants mainly remain “outsiders” and lack access to protections and stable contracts [

32]. A further gap concerns the measurement of job satisfaction in migration studies. Job satisfaction scales are widely validated in organization research, but their application to migration research and migrants’ data remains very limited. The foundational work by Spector [

33], Warr [

34], and Locke & Latham [

35] highlight that job satisfaction is multidimensional, taking into consideration extrinsic, intrinsic, and relational aspects of the work and that validated indicators are important for constructing validity and comparability. Still, migration studies rarely discuss such measures to align with the unique socio-economic context of migrant workers. Despite these advances, there are relatively few studies that combine multi-dimensional job satisfaction, profile analysis, and inferential modelling for South Asian migrants in Italy. This study fills this gap by combining descriptive frequency analysis, MCA-based clustering of satisfaction domains, and multinomial regression prediction of structural indicators such as nationality group, citizenship, and gender. In the process, the study bridges the gap between subjective experience and structural differentiation, moving forward to satisfaction paradoxes and employment inequality in Italy. By linking subjective job evaluations with structural markers, this study aligns with the recent emphasis on more integrative approaches for understanding inequalities for migrants in labour markets [

8,

9].

In general, the literature underlines the complexity of migrant job satisfaction in Italy: migrants may have acceptable levels of job satisfaction despite precarious jobs, and their satisfaction is shaped by legal inclusion, type of work, and migrant motivation. Still, there remain key gaps to identify latent satisfaction typologies and to understand how such patterns link with nationality, legal status, and gender—the key gaps this study addresses by the multistep analytical framework. Overall, the reviewed literature indicates that subjective job satisfaction among migrants cannot be explained independently of the structural factors of their involvement in the labour market. Segmented labour market theory puts emphasis on the fact that migrants have been disproportionately pushed down the low wage, insecure ladder of mobility into low wage segments, whereas both human capital and credential recognition perspectives explain why there is still underutilization of skills and overqualification. Intersectional approaches also place greater importance on the combined effects of nationality, gender, and legal status to formulate differentiated labour market roles and experiences. Simultaneously, studies on migrant well-being indicate that job satisfaction is also determined by not only the objective features of a job, but also the expectations, reference groups, and social meaning of work that migrants develop. Combined, these observations suggest the probability that the pattern of satisfaction differs in a systematic manner by migrant groups as well as by structural positions. These theoretical considerations form the basis of the analytical focus of the study and guide the specific expectations and objectives of the study that are stated in the objectives section of the paper.

3. Key Objectives

This research study has the following specific objectives.

To examine job satisfaction distribution among five major work dimensions: wages, job security, working hours, workplace relations, and careers, among South Asian migrants in Italy.

To determine the latent trends of job satisfaction by Multiple Correspondence Analysis (MCA) and hierarchical cluster analysis, and to develop typologies of different perceived employment experiences.

To test the relationship between these dimensions of satisfaction and latent profiles with structural identifiers of migrant labour market location, namely nationality, Italian citizenship, and gender, through multinomial logistic regression.

4. Material and Methods

A three-step quantitative analysis is applied in this research study to examine the connection between migrant workers’ satisfaction with various work conditions and their demographic and structural position in the host country’s labour market. The analysis specifically investigates how job satisfaction differs among nationalities (Step 1), identifies hidden satisfaction-based clusters of migrants (Step 2), and assesses how the patterns of satisfaction are linked with nationality, citizenship, and gender (Step 3). Mixed software was utilized, with frequency analysis and regression modelling conducted within SPSS 29 and multivariate clustering conducted using R 2023.06.0. Such a multi-step framework allows the research study to move from descriptive patterns to latent structure identification as well as finally towards explanatory modelling.

4.1. Data Preparation

The dataset used for this research has been drawn from ISTAT, comprising migrants from five South Asian nationalities: Pakistani, Indian, Bangladeshi, Sri Lankan, and Nepali. The data entails those that were interviewed by ISTAT. Missing values on any of the job satisfaction measures included the respondents in the listwise exclusion, and where relevant, descriptive weights offered by ISTAT were used to create representativeness. Primary demographic variables included nationality, sex, citizenship in Italy, and employment type. Job satisfaction was evaluated using various self-reported items on various qualities of work. Responses on items were measured on a 0–10 numeric scale or ordered categories, which were harmonized into low, medium, and high categories of satisfaction to allow comparability of responses across indicators.

The operationalised dimensions of analysis were based on the standard indicators of ISTAT as the following seven dimensions of satisfaction:

Satisfaction with job overall

Satisfaction with wage/income

Satisfaction with working hours

Satisfaction with workplace climate and social relations

Satisfaction with career advancement opportunities

Satisfaction with job security

Satisfaction with commuting conditions

These items are the fundamental dimensions of job quality and are consistent with the multidimensional models of satisfaction widely used. All the indicators of satisfaction were categorical to the MCA.

4.2. Step One—Frequency and Percentage Distributions by Nationality

The initial analytical step was descriptive. Frequency counts and percentage distributions for each of the variables of satisfaction were computed for different national groups. This enabled the determination of trends of satisfaction and variability across nationalities. Crosstabulations were conducted to contrast how the levels of satisfaction were distributed (e.g., low, moderate, high) among Pakistani, Indian, Bangladeshi, Nepalese, and Sri Lankan migrants. The differences in perceptions across the different nationalities were tested through chi-square tests to determine whether or not these differences were significant. Where possible, weighted estimates were provided.

4.3. Step Two—Multiple Correspondence Analysis (MCA) and Cluster Analysis

The second step sought to unveil concealed structures of satisfaction among migrants through Multiple Correspondence Analysis (MCA). MCA is a multivariate exploratory technique used to determine underlying patterns in categorical data. It is conceptually parallel to principal component analysis, but it is particularly adapted to categorical variables; hence, it is appropriate for the set of satisfaction indicators used in this research.

Let X be a matrix of individuals by categorical variable data. MCA analyzes the Burt matrix (a matrix of all cross-tabulations between variables) and reveals new concealed dimensions (factors) explaining variance (inertia) in the data. Normalization of the Burt matrix, extraction of eigenvalues, and retention of dimensions were based on the standardized procedures in the analysis: the proportion of inertia explained and the interpretability. The categories were considered to make contributions to each dimension in an attempt to establish which satisfaction indicators exerted the strongest influence on each latent factor.

The coordinates of the individuals on the first two dimensions of MCA were extracted and plotted to observe groupings. Individual variable category contributions to each dimension were calculated as follows:

where

fij: relative frequency of category j for individual i

dij: coordinate of category j on dimension k

λk: eigenvalue of dimension k

Subsequently, hierarchical cluster analysis (Ward’s method) was applied to the dimensions of the MCA to group those with similar satisfaction profiles. The number of clusters applied was the best, as the dendrogram, scree plot of inertia loss, and substantive interpretability were viewed together. Three clusters were identified and labelled based on their mean satisfaction levels:

Cluster 1: Low Satisfaction

Cluster 2: Moderate/Mixed Satisfaction

Cluster 3: High Satisfaction

Cluster-wise average satisfaction scores for all variables were calculated, and profiles were also charted with bar plots. Internal cluster validity was calculated by comparing between-cluster separation and within-cluster homogeneity.

4.4. Step Three—Multinomial Logistic Regression

The third step of the analysis utilized multinomial logistic regression to investigate the effect of major demographic and structural characteristics on the level of satisfaction of migrants. In this analysis, the harmonized satisfaction indicators were converted into three ordered categories of satisfaction, namely low, medium, and high, which were used as the dependent variable. The high category of satisfaction was determined as the reference category of comparative estimation. The main independent variables were the region of residence in Italy, group of nationality, year of arrival in Italy, household size, and sex. These predictors include the fundamental structural and demographic variables that might influence subjective perceptions of job quality.

The outcome of satisfaction was evaluated on six domains, and they were overall job satisfaction, wage satisfaction, satisfaction with workplace climate and social relations, satisfaction with working hours, job security, and satisfaction with commuting distance and time. Separate multinomial models were estimated in each of the satisfaction domains to determine whether the determinants were different across dimensions of job quality.

Multinomial logistic regression predicts the probability of belonging to a nominal outcome category as opposed to a reference category. The general model is:

where:

Y: outcome variable with J categories

r: reference category

βpj: regression coefficients for category j

Xp: predictors (satisfaction variables)

Model diagnostics involved model fitting statistics (likelihood ratio tests), pseudo R-square (e.g., Nagelkerke), and likelihood ratio tests of each predictor. Odds ratios (Exp(B)) and 95% confidence intervals were given as parameter estimates. The level of statistical significance was established as being less than p < 0.05.

In order to be robust, sensitivity tests were conducted through the estimation of models with and without population weights, and evaluation of multicollinearity among predictors. The constraints associated with possible self-selection into work, the under-representation of irregular migrants, and cross-sectional data are admitted.

5. Results

5.1. Frequencies and Percentages Distributions of Socio-Economic Indicators

5.1.1. Level of Satisfaction with Current Job

Table 1 shows the self-reported job satisfaction distribution among South Asian migrants in Italy on a scale of 0 to 10. The overall distribution shows that the scale is mostly positively rated on job satisfaction, with the largest concentration at scale 8 (28.2%), and the next significant percentages at scales 9 (8.7%) and 10 (10.7%). Cases of explicit dissatisfaction were few, with reports of low satisfaction (0–3) being relatively rare. Only a small proportion (1.6) reported don’t know, implying that there is less ambiguity or indecision as far as job satisfaction is concerned. The respondents of Bangladeshi nationality showed a high level of satisfaction in all groups of nationalities, with high percentages at scales 7 and 8, and small percentages indicating dissatisfaction. The same was observed with Sri Lankan migrants with the majority of the answers ranging between 6 and 8, which again supported high levels of moderate to high satisfaction. Among Indian migrants, the highest proportion was found to be at scales 8 (30.4%) and 7 (26.4%), showing strong, positive ratings with low variation. The distribution of Pakistani migrants was more diverse, but satisfaction was still mostly positive, specifically at scales 7 (30.4%) and 8 (25.5%). Pakistani migrants were somewhat more concentrated in the middle-range and showed lower levels of satisfaction when compared to other groups (e.g., scales 5 and 6), which shows they are more heterogeneous. These patterns were mostly chosen by Nepali migrants at scales 7–9, but since the sample is small, it is not possible to interpret the patterns. Combined, the findings indicate that South Asian migrants in Italy, on average, report moderately to highly on the dimension of job satisfaction, with only a small fraction of them opting for the low side of the scale. The similarity in the percentage of mid-to-high evaluations of the work of all national groups indicates that positive job assessment is quite common, even though the majority of migrants are concentrated in the low- or semi-skilled area. The occurrence of low levels of satisfaction, however, albeit small, shows that there are negative job experiences that might be linked to disproportions in the working conditions or opportunities in the working conditions in a certain group in the labour market.

5.1.2. Level of Satisfaction with Wage

Table 2 indicates the wage satisfaction distribution of South Asian migrants in Italy on a 0–10 scale, with an added don’t know category. In general, wage satisfaction can be characterized by the concentration in the middle-to-high section, where the greatest proportions are voicing scales 7 (27.8%), 6 (22.6%), and 8 (20.6%). Most of the responses indicating the lowest levels of satisfaction (0–2) were restricted to a minor fraction of the sample (1.8%). All respondents (11.5% overall) scored high satisfaction (9–10), and 1.6% of all respondents responded with don’t know. At the nationality level, there was a balanced distribution of Bangladeshi migrants with a bias towards the middle-range categories, especially scales 6 (27.4) and 7 (26.7). An excellent minority (7.1) provided the greatest level of satisfaction, and the proportion of strong discontent was very small. Sri Lankan migrants experienced a prevalence of mid-range satisfaction, too, with most choosing scales 6 or 7, and only a minor portion gave low scores. The level of dissatisfaction was low but few, indicating that perceptions of adequacy of wages among this group were overall stable. Indian migrants were found to be more satisfied with their wages, with the highest proportion of 7 (29.7%), 8 (25.6%), and 6 (17.7%) scales. The number of Indian respondents who expressed dissatisfaction (scale less than 3) was very low, and this is a sign that there were consistently positive wage ratings in this group. Nepali migrants, most of whom responded to the question with scales 7–9, were found to experience high wage satisfaction, though there were only a few of them. The moderately positive distribution of Pakistani migrants shows the highest percentage of scales 7 (29.9) and 6 (20.6), which nevertheless has a relatively broader distribution in the lower categories than the other groups. Generally, the findings indicate that most South Asian migrants are satisfied with their wages, which are considered to be sufficient based on the high concentration in middle and high levels of satisfaction. Nevertheless, the existence of middle levels of satisfaction suggests that the wage terms are not entirely satisfactory among a group of migrants, which suggests the direction in terms of earnings or wage advancement.

5.1.3. Level of Satisfaction with the Climate and Social Relations

Table 3 shows the satisfaction level of workplace climate and social relations of South Asian migrants in Italy in terms of a 0–10 scale, along with the option of don’t know. The problem responses were mainly in the mid-to-high satisfaction band, with the highest percentages of 26 and 29.1 choosing scales 7 and 8, respectively, and then scale 6 (16%). The given tendency implies rather positive attitudes towards interpersonal relationships and the workplace. The likelihood of low satisfaction (scales 0–3) was low, and less than 1 percent of respondents were reported to be dissatisfied. High levels of satisfaction were also common, where 11.3% chose scale 9 and 10.4% chose scale 10. Only a small proportion (1.6) gave the response of not knowing, which may imply that there is a limited degree of uncertainty in assessing work relations.

There was high satisfaction as reported by Bangladeshi migrants, with most of the respondents choosing high satisfaction scales 7 or 8, and almost none of the lower-satisfaction scales. The same was observed among Sri Lankan migrants, where most of the responses were 7 or 8, and there were very few dissatisfied. Indian migrants reported a very high degree of satisfaction as well, and the clustering was quite high at the upper ranks (scales 7–9), consistently. Pakistani migrants were found to exhibit more diverse allocation of satisfaction; although, most of them also indicated mid-to-high levels of satisfaction, which were especially higher in the range of 7–10. All within a small sample, Nepali migrants only responded in the 7–9 range, indicating consistently positive events.

In all the national groups, the satisfaction levels with workplace climate and social relations were rather high, which means that most of the respondents had favourable interpersonal environments. These findings indicate that a good proportion of migrants feel that their places of work are inclusive and accommodating, as there are favourable interactions among the employees. The fact that dissatisfaction is not high suggests that few cases of negative interpersonal experiences or exclusionary dynamics have been reported. Still, the fact that there are a few low scores implies that there are still isolated cases of bad relations at the workplace that are worth focusing on.

5.1.4. Level of Satisfaction with Job/Career and Business

Table 4 presents the results of South Asian migrants’ satisfaction with their job/career and business prospects on a 0–10 scale, with an option of don’t know. On the whole, career and business satisfaction is more concentrated in the middle ranges, with the largest percentages of 22.8, 20.3, and 13 choosing scales 6, 7, and 5, respectively. It is also interesting to note that a significant minority (11.2%) chose scale 0, which means highly dissatisfied. The further responses between scale 1 and 4 also show the existence of moderate dissatisfaction among the sample. Only a low percentage (1.9) chose not to respond.

Scale scores 5–7 indicate moderate satisfaction among Bangladeshi migrants, with a smaller but significant percentage giving a score of 0, which means strong dissatisfaction. The concentration of Sri Lankan migrants fell in scales 6 and 7, but 8.6% with strong dissatisfaction were present in scale 0. Indian migrants were more polarized, with a large portion choosing high levels of satisfaction (scales 7 and 8) and an equal percentage choosing dissatisfaction (15.9% at scale 0). Pakistani migrants indicated rather moderate dissatisfaction (especially at scales 6 and 7), but 11.3% of the respondents were strongly dissatisfied at scale 0, which implies significant variability in the group. Nepali migrants, despite being a small subgroup, indicated high levels of satisfaction generally, with most of their ratings ranging between scales 6 and 9.

These trends indicate a two-sided satisfaction picture: on the one hand, a substantial portion of migrants are satisfied with their career and business opportunities (moderate to high); on the other hand, a large population of migrants is obviously dissatisfied. The difference in answers can be connected to differences in the mobility of the career or sectoral opportunities, or a mismatch between migrants’ skills and jobs. Reduced levels of satisfaction can also be linked either to reduced promotion prospects, entrepreneurship challenges, or language or credentialing issues.

5.1.5. Level of Satisfaction with Job Security

The distribution of the level of job security satisfaction of South Asian migrants in Italy is provided in

Table 5, which is designed on the 0–10 scale with the addition of another category of response based on the don’t know designation. On the whole, job security satisfaction is concentrated in the upper-mid-range, where the largest percentages chose scales 8 (26.1%), 7 (22%), and 6 (19.8%). The level of satisfaction was high, with 7.9% choosing scale 9 and 8.7% choosing scale 10. There were very few poor ratings of job security (3.5% between scales 0–2), and 1.6% of the respondents chose don’t know.

It can be seen that there are differences in the distribution of job security satisfaction between nationality groups. Indian migrants had the greatest overall job security satisfaction, with a significant concentration on scales 7–9 and a high percentage (30.4) choosing scale 8. A very low proportion (2.7) of Indian respondents noted low satisfaction (0–3), which revealed that this group had extensive confidence in their job stability. Similar results were reflected in the responses of Bangladeshi and Sri Lankan migrants, who were found to be mostly mid-to-high satisfaction, with majority of the scales falling between 6 and 8, as well as there being few cases of dissatisfaction. Pakistani migrants exhibited a greater dispersion of satisfaction categories, with most in categories 7–8, and a slightly larger proportion reporting low satisfaction than other nationalities. Within the Pakistani respondents, only a small proportion (2.5%) chose not to answer. Nepali migrants—who were in very small number—recorded very high job security satisfaction, almost all of whom indicated scale 8 or 9.

On the whole, the majority of South Asian migrants stated that they felt safe in their workplaces, which implies that job stability is also a rather powerful feature of their labour market experience. Nonetheless, the dispersion within national categories, especially between Pakistani and some of the Bangladeshi and Sri Lankan workers, means that job security is not equally shared, which may become a manifestation of different sectional distribution or contractual stability.

5.2. Latent Structures of Job Satisfaction Among Migrants

5.2.1. Latent Structure Identification via Multiple Correspondence Analysis (MCA)

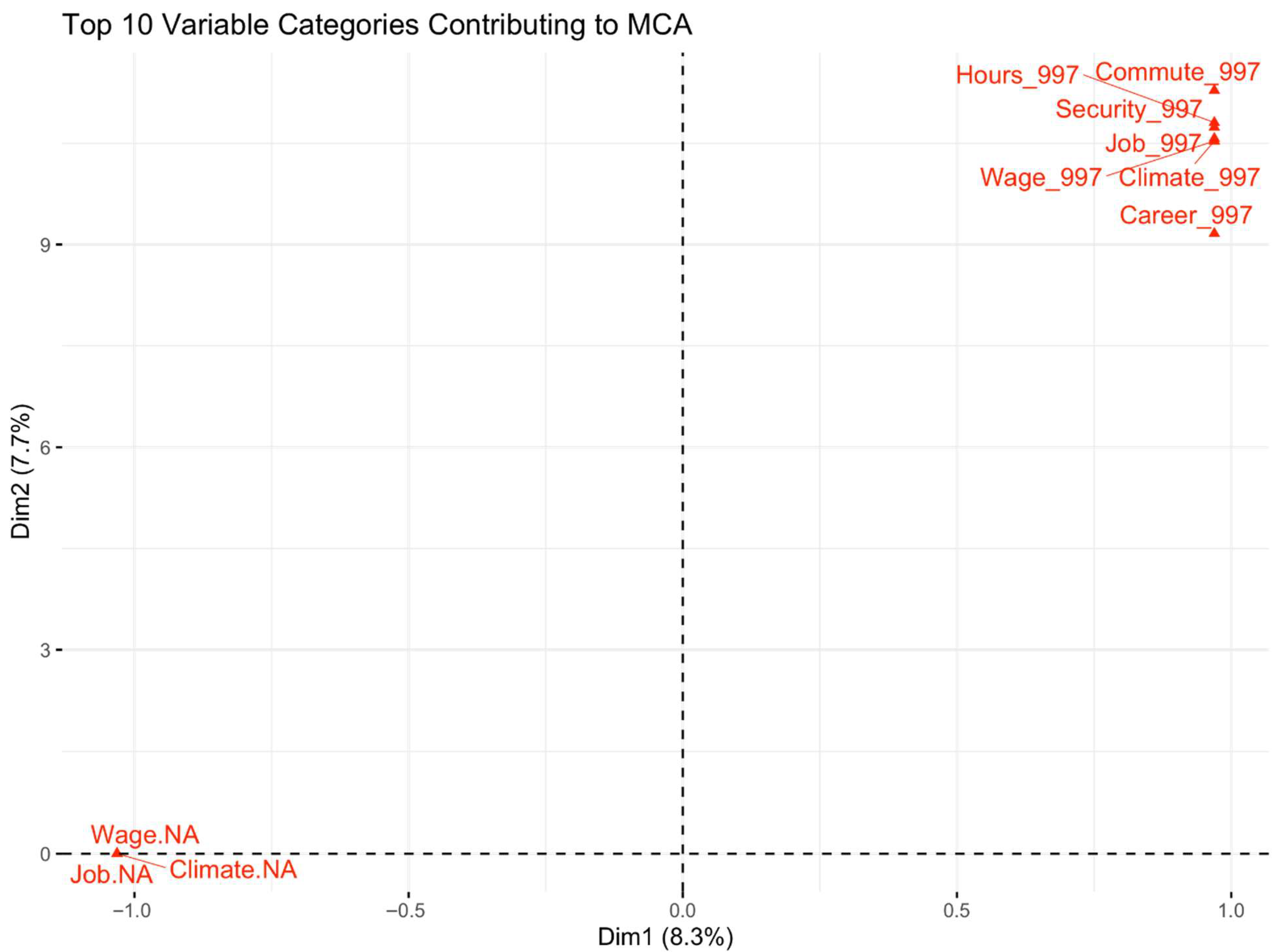

To determine the patterns that were found to be underlying job satisfaction, Multiple Correspondence Analysis (MCA) was carried out with seven categorical variables, which were overall job satisfaction, wage satisfaction, working hours, job security, workplace climate and social relations, career prospects, and commuting conditions. All satisfaction variables were recoded into ordered levels of category and were changed to active variables in the MCA. The MCA biplot presented in

Figure 1 illustrates the projection of individuals and the categories of satisfaction on the first two dimensions. The biggest portion of inertia was explained by Dimension 1 and Dimension 2, which are the most important latent variables that were used to explain the difference in responding to satisfaction. These dimensions were used to interpret the cumulative variance reflected by them.

The nominal pattern of spatial organization of categories and people denotes evident patterns of co-occurrence. The high satisfaction categories (e.g., Wage 10, Security 10, Career 10) also are concentrated on the positive side of the Dimension 1, indicating that people who report high satisfaction in one of the areas are likely to report high satisfaction in many areas. On the contrary, the low-satisfaction and missing variables (e.g., Job 0, Wage NA) are located in the middle or other regions of the plot, which is an indication of lower levels of satisfaction or uncertainty.

There were two interpretable latent factors:

Dimension 1 is an overall satisfaction gradient, where scores are positive when there is high satisfaction in a variety of aspects of the job, and negative when there is low satisfaction or indifference.

Dimension 2 splits the respondents with consistent patterns of satisfaction, as opposed to inconsistent or missing ones, and represents the variation that is due to uncertainty or inconsistent reporting.

5.2.2. Variable Contributions to the MCA Space

It is necessary to evaluate the contribution values in contribution dimensions (using squared cosines) in order to determine which categories contributed to the strongest MCA dimensions.

Figure 2 shows the top ten contributing categories in the first two dimensions, respectively.

High satisfaction levels were overrepresented in Dimension 1, which confirmed the fact that this dimension represents mostly the opposition between positive and negative satisfaction ratings. This trend suggests that job security, wage satisfaction, and career opportunity satisfaction have the greatest contribution to distinguishing respondents on the general satisfaction axis. On the other hand, missing/unspecified responses (e.g., NA categories) were stronger contributors to Dimension 2, which implies that this dimension represents uncertainty or inconsistent response behaviors.

These patterns of contributions validate the applicability of the chosen variables of satisfaction in attaining relevant variation in subjective experiences in the labour market.

5.2.3. Cluster Identification Based on MCA Dimensions

The MCA coordinates were subjected to hierarchical cluster analysis (Ward method) to cluster the respondents into groups that had similar satisfaction profiles. The dendrogram inspection, inertia loss, and interpretability were used to identify a three-cluster solution (

Figure 3).

The geometrical location of clusters on the MCA map is in line with the interpretive organization of the two dimensions.

Cluster 3 is located in the high-satisfaction area of the plot, which is consistent with such categories as “Wage10” or Security10” that represent a high level of satisfaction in all domains.

Cluster 1 is the opposite of Cluster 3 and is characterized by lower or uncertain satisfaction responses so that the evaluations are generally unfavourable.

Cluster 2 is between the two extremes and represents a group of respondents with mixed or moderate satisfaction profiles, which commonly report favourable assessments in one or more domains but not others.

Cluster cohesion was different: Cluster 3 had high internal homogeneity, whereas Cluster 1 was more scattered and had more heterogeneity between the respondents who were less satisfied.

5.2.4. Profiling Clusters Using Satisfaction Scores

To further describe the clusters, the mean score of the original 0–10 responses of satisfaction for each of the seven satisfaction indicators was calculated (

Figure 4).

The mean scores reveal substantial between-cluster differences.

The mean scores of Cluster 3 were the highest of all the domains of satisfaction, which proved that it was the high satisfaction group.

Cluster 1 had the lowest scores, particularly on wages, job security, and commuting conditions, which implies experiences that were related to more precarious jobs.

Cluster 2 also showed a moderate or mixed picture of satisfaction, as it had intermediate scores.

These profiles show that there are different regimes of migrant employment experience, with a consistently positive assessment on one end, and dissatisfaction with multiple dimensions on the other end.

5.3. Multinomial Logistic Regression

Multinomial logistic regression models were estimated in series to determine how far region, nationality, household size, sex, and year of arrival in Italy predict levels of satisfaction on six outcomes that are related to employment. All models used high satisfaction a reference.

5.3.1. Model Fit and Explanatory Power

In all six of the outcomes, the complete models performed much better compared to the intercept-only models (all p < 0.001), which means that the predictors jointly distinguished the three levels of satisfaction (low, medium, and high).

The values of Nagelkerke R2 were around 0.06–0.09, which is a normal attitudinal result in such studies of social science. Even though they are small, these values suggest that structural and contextual features make a significant contribution to the difference in satisfaction.

5.3.2. Key Predictors of Satisfaction Across Outcome Domains

- (a)

Regional variation: Region proved to be the most reliable and effective foreteller of all outcomes. Greater chances of reporting low or medium satisfaction compared to high satisfaction were found in migrants who lived in some areas. The region odds ratios (ORs) were significant in almost all comparisons, which highlights the high influence of territorial labour-market conditions in the development of subjective job evaluations.

- (b)

Nationality differences: Nationality was also a significant contributor to the difference in satisfaction especially between job satisfaction, wage satisfaction, and job security. In a number of the models, Indian and Sri Lankan migrants had a much lower likelihood to report high levels of satisfaction than the reference group (Pakistan). On the contrary, certain categories of people (e.g., Nepal in commuting satisfaction) were found to have significantly more odds of being poorly satisfied.

- (c)

Household size: The effect of household size was significant but not large in a number of the models (significant wage satisfaction and commuting satisfaction), and the larger the household size, the larger the odds of reporting medium rather than high satisfaction. This implies a possibility of economic or time-related stress relating to bigger families.

- (d)

Sex: Sex was not usually used as an important predictor, with the exception of the commuting model, in which male and female respondents showed differences in travel burden experiences.

- (e)

Year of arrival: The year of arrival was always not significant, and that is why the duration of stay in Italy is not a significant decision that can determine the level of satisfaction in the areas under consideration.

5.3.3. Outcome-Specific Highlights

Even though the predictors acted consistently across models, it is important to note that there are a number of outcome-specific patterns:

Job Satisfaction: Region and nationality had a big role to play in the reduction of satisfaction. There was no significant effect of household size or sex (

Appendix A:

Table A1,

Table A2,

Table A3 and

Table A4).

Wage Satisfaction: The significant determinants were region, nationality, and household size. High levels of satisfaction were less likely among migrants in some regions as well as among some nationality groups (e.g., India) (

Appendix A:

Table A5,

Table A6,

Table A7 and

Table A8).

Climate and Social Relations: The only strong predictor that had significant impacts was Region; the impact of nationality and demographic variables remained consistent (

Appendix A:

Table A9,

Table A10,

Table A11 and

Table A12).

Distance/Time of Commute: The distance/time of commuting is a socio-spatial experience that predicted levels of satisfaction significantly in region, nationality, sex, and household size (

Appendix A:

Table A21,

Table A22,

Table A23 and

Table A24).

5.3.4. Summary Interpretation

In all areas of satisfaction, the most significant predictors were found to be regional location and nationality; sex, household size, and year of arrival had weaker and more domain-specific effects. In general, the findings show that the subjective labour-market experiences of migrants are influenced by territorial and ethnicized structural variables rather than individual demographic variables. These results support the role of regional labour-market factors and nation-specific labour-market trajectories in explaining differences in the migrant job satisfaction in Italy.

6. Discussion

The results of the study show some clear and systemic patterns of South Asian migrants in Italy gauging the various dimensions of their employment experiences. The results of the descriptive statistics, which are backed up by MCA and clustering, indicate that satisfaction levels tend to be moderately high or high in most job areas. Nevertheless, the skewness of the latent profiles of satisfaction also implies heterogeneity, where there is also a distinct group of respondents that face continuously low levels of satisfaction with wages, job security, and career prospects. The multidimensionality of satisfaction can be highlighted by the three-cluster solution based on MCA, because one cluster always reports positive experiences, another reports mixed experiences, and another reports strong dissatisfaction. These trends indicate that migrant job satisfaction cannot only be determined at the aggregate level; it must be analyzed in terms of structural positions, employment pathways, and contextual differences.

The outcomes of the regression enrich this interpretation by showing that individual characteristics are the least determining factors of satisfaction, but contextual and structural factors are the strongest ones. In all six of the explored outcomes, region and nationality stand out as the most consistent predictors of either low or medium satisfaction with high satisfaction. This result is in line with the old debate on migration and labour market segmentation studies that adopt an opportunity structure perspective (unequal) and a territorial inequality approach (disparity) towards the experiences of migrants in the labour market, rather than being based only on individual characteristics. The regional variation in satisfaction probably reflects the differences in labour demand, stability of the contracts, sectoral composition, and the quality of working conditions in the Italian regions. This high impact of nationality suggests that the occupation performance of migrants is still stratified on ethnicized lines, as is corroborated by findings that other migrant groups are selecting different occupational niches and have disparate chances of being in precarious jobs. The fact that nationality still has an independent impact, despite the regulation of the region and demographics, only strengthens the idea of the existence of ethnic punishments that are part of the workforce sorting mechanisms.

Household size has significant yet small relationships with the chosen outcomes, especially wage and commuting satisfaction, implying that economic demands and inability to spend time with larger families can be determinants of a migrant’s perception of labour conditions. Conversely, sex and year of arrival are not significant predictors of satisfaction in most of the models. The lack of meaningful effects of year of arrival also indicates that years of residence is not a guarantee of ironing out labour market inequalities or converting years of residence into enhanced subjective experiences—which is an important finding that refutes some linear integration assumption. In the same direction, the minimal impact of sex can also be attributed to the gendered nature of the migrant labour markets in Italy, where the gendered distribution of men and women in low-skilled and precarious jobs can be a way of reducing the gap in gender in subjective appraisals.

Combined, the empirical evidence suggests two major conclusions. To begin with, the subjective job satisfaction among South Asian migrants is not just a factor of individual optimism or accommodation, but is entrenched in structural reality. The difference in the level of satisfaction of migrants in areas where labour conditions are less favourable, or in migrants of a particular nationality, are systematically lower in several job dimensions. Second, the relative presence of a very high sense of satisfaction combined with the recorded structural inequalities resonates with the migrant satisfaction paradox. The high-satisfaction cluster also indicates that, in the case of most migrants, it can be viewed that employment in Italy could be better than employment in the country of origin, even when the objective conditions are precarious; however, the fact that there is also a definite low-satisfaction cluster indicates that this paradox is not universal.

The contribution of the study to the migration literature is that it incorporates descriptive, multivariate, and predictive research methods to locate the subjective labour market experience of a large and multifaceted migrant population. The analysis helps fill a literature gap whereby satisfaction is usually analyzed separately and not in the context of the wider socio-economic frameworks. The implications of the findings have significant policy implications, as better governance of the regional labour market, more effective regulation of the sphere of precarious employment, and more focused provision of migrant groups vulnerable to cumulative disadvantage can result in significant benefits to the quality of jobs and improved outcomes of integration. Enhancing awareness of qualification, overcoming mobility restrictions, increasing access to stable contracts, and enhancing local integration infrastructures are tangible channels in terms of which regional and national gaps in contentment could be minimized.

In general, the findings highlight the importance of the fact that migrant job satisfaction is context-specific, multi-layered, and dependent on structural opportunities instead of on individual or demographic characteristics. These dynamics are critical in understanding how the interventions can be designed to facilitate equitable labour market integration and improve the well-being of migrant communities in Italy.

7. Conclusions

This study explored how subjective job satisfaction among South Asian migrants in Italy reflects, as well as reinforces, overall patterns of structural differentiation within the labour market. While previous studies have concentrated on objective labour market experiences—i.e., wage gaps, legal precariousness, or occupational segregation—this research shifted its focus to migrants’ self-stated experiences of job satisfaction along different dimensions. The research develops a more detailed picture of how migrants assess themselves in the Italian labour market by looking at the patterns of their satisfaction according to factors related to the structural markers of nationality, region of residence, household size, and sex. To this end, the research applied a three-stage quantitative design. Firstly, descriptive frequency and percentage distributions were used to explore how satisfaction with pay, job security, working hours, social climate, and career advancement varied by nationality. Secondly, Multiple Correspondence Analysis (MCA) and cluster analysis were performed to create a typology of satisfaction profiles, which identified three groups of migrants: low satisfaction, moderate satisfaction, and high satisfaction. Lastly, multinomial logistic regression was performed was used to determine the relationship between the structural and demographic variables (region, nationality, sex, household size, and year of arrival) and the probability of falling into the low, medium, or high category of satisfaction. This mix of descriptive, exploratory, and explanatory techniques facilitated a multi-layered examination of subjective labour market positioning.

The results produced noteworthy patterns. In almost all job dimensions, region and nationality proved to be the same predictors of satisfaction, which proves that structural and territorial variables are much stronger than individual population characteristics. Household size exhibited moderate relationships in the choice of areas, whereas sex and year of arrival were not essential in most of the satisfaction results. The MCA and clusters also indicated that the experiences of migrant workers cannot be homogenous but can be characterized under three different regimes of satisfaction that are always positive, always negative, or always mixed. Collectively, these results demonstrate that the presence of high levels of so-called reported satisfaction with objectively precarious employment conditions reflects aspects of the so-called migrant satisfaction paradox.

By connecting structural location to subjective satisfaction, this research calls for greater attention to migrant well-being, not only in economic terms, but also in terms of the quality of the work experience. Policies can reduce inequalities and improve the integration of migrants by focusing on regional inequalities, job security, and qualification credibility, and on groups that experience a cumulative disadvantage. The paper adds to the current discussions on the segmentation and subjective integration of the labour market, as well as to the significance of considering job satisfaction as a personal assessment, and as the manifestation of the overall structural limitations.

8. Limitations

There are a number of limitations involved in this study that must be considered during interpretation of the results. To begin with, the analysis is based on secondary data provided by ISTAT, limiting the scope of available variables. Critical factors that determine job satisfaction, including the terms of the contract, industry-specific factors in working conditions, the English language, or discrimination cases, could not be monitored, and this constrained the explanatory capacity of the models. Second, the indicators of satisfaction are self-reported and are prone to biases in responses, such as the process of adaptation and the cultural conditioning of dissatisfaction expression. This is especially so in the context of migration, whereby the satisfaction paradox can be based on relative expectations, as opposed to the actual job quality.

Third, MCA and cluster analysis are very useful in terms of their insights into latent satisfaction structures, but both methods are nonparametric and can be impacted by decisions related to coding and sample illustration. The stability and generalizability of cluster profiles may also be constrained because of small subsamples of certain nationalities (e.g., Nepali migrants). Fourth, the data is cross-sectional and thus the data cannot be used to infer causality. Even though the models reveal links between the structural variables and the levels of satisfaction, they are not able to show the direction of effects or reflect the change through time.

Lastly, regional variation was also gauged on an aggregate level, and this can conceal some crucial within-region differences in dynamics and local integration conditions in the labour market. Further studies may be able to add to these results by employing longitudinal or mixed-methods studies, more detailed measures of job quality, and more specific regional or sector data.