Mental Health Symptoms and Alcohol Counseling Among Young Adults: Implications for Equitable Preventive Care

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Data

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Health Provider Advice on Alcohol in the Past 12 Months

2.2.2. Sex Assigned at Birth and Sexual Identity

2.2.3. General Anxiety Disorder (GAD)-7 and Personal Health Questionnaire (PHQ)-8

2.2.4. Sociodemographic Variables

2.2.5. Health-Related Variables

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Prevalence of Medical Provider Advice on Alcohol

3.2. Logistic Regression Analyses of Medical Provider Advice on Alcohol

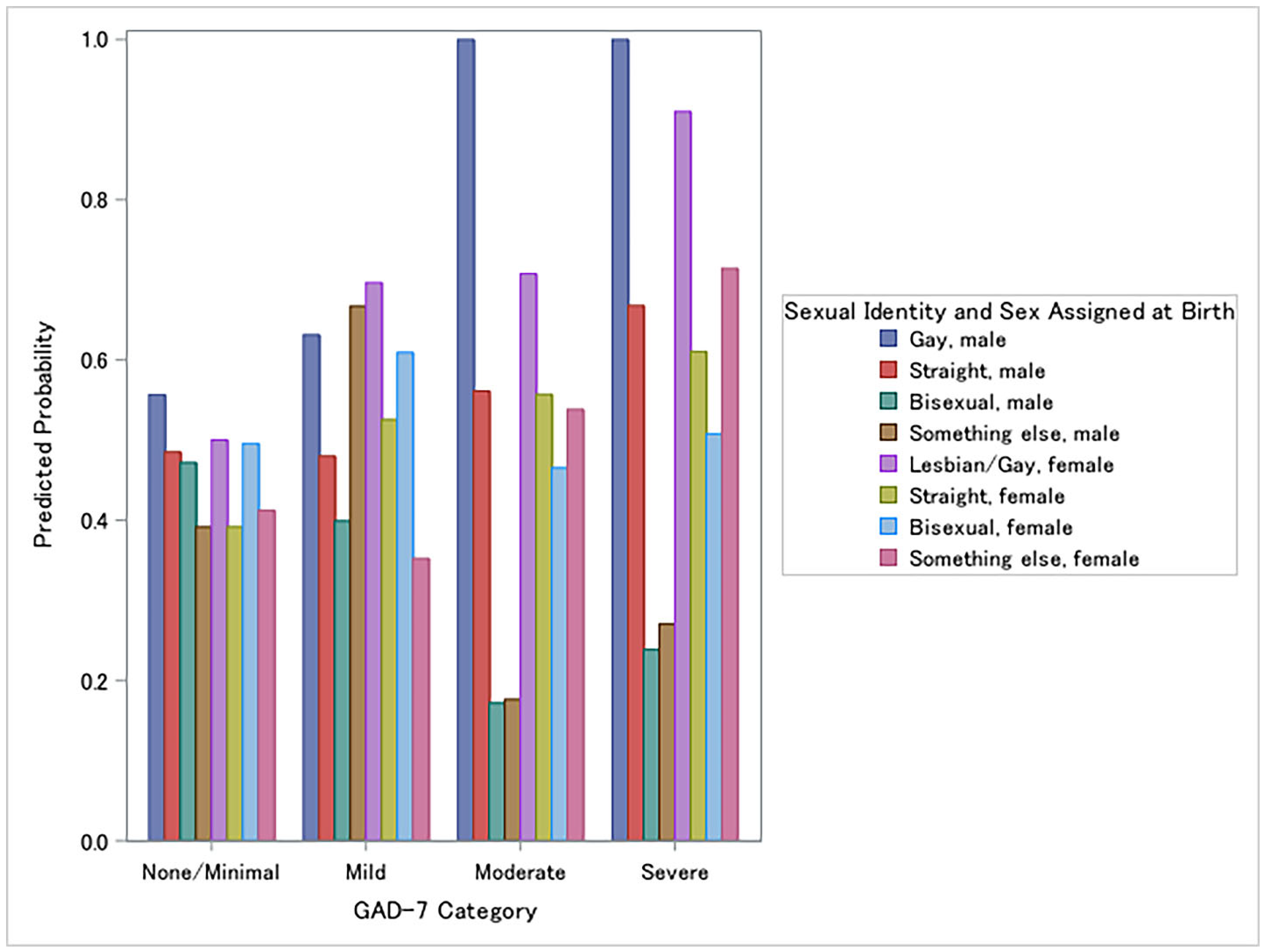

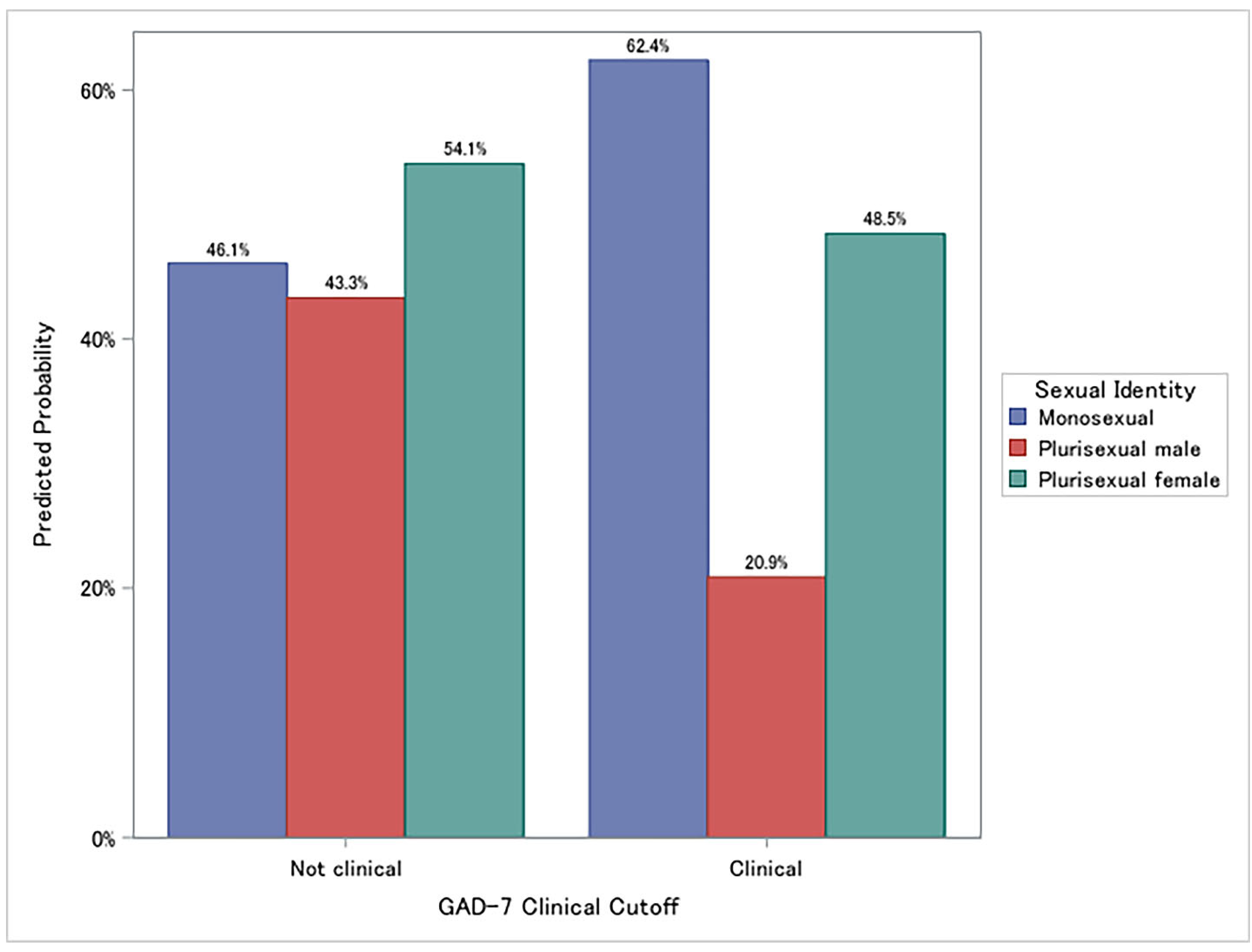

3.3. Moderation Effects of Sex/Sexual Identity on Medical Provider Advice on Alcohol

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

4.2. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wisk, L.E.; Weitzman, E.R. Substance use patterns through early adulthood: Results for youth with and without chronic conditions. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2016, 51, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrick, M.E.; Terry-McElrath, Y.M.; Kloska, D.D.; Schulenberg, J.E. Shifting age of peak binge drinking prevalence: Historical changes in normative trajectories among young adults aged 18 to 30. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2019, 43, 287–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Substance Abuse Mental Health Services Administration. Key Substance Use and Mental Health Indicators in the United States: Results from the 2021 National Survey on Drug Use and Health; HHS Publication No. PEP23-07-01-006, NSDUH Series H-58; Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration: Rockville, MD, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Terlizzi, E.P.; Zablotsky, B. Symptoms of Anxiety or Depressive Disorder Among Adults: United States, 2019 and 2022, National Health Statistics Reports, No. 213; National Center for Health Statistics, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Hyattsville, MD, USA, 2024; Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhsr/nhsr213.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Puddephatt, J.A.; Jones, A.; Gage, S.H.; Heron, J.; Hickman, M.; Munafo, M.R. Associations between anxiety, depression, and alcohol use disorders in the UK Biobank. Addiction 2022, 117, 357–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadland, S.E.; Marshall, B.D.L.; Kerr, T.; Qi, J.; Montaner, J.S.G.; Wood, E. Alcohol use among sexual minority and heterosexual youth: A population-based study of risk and protective factors. J. Adolesc. Health 2016, 58, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahill, S.; Makadon, H.J. Sexual orientation and gender identity data collection in clinical settings and in electronic health records: A key to ending LGBT health disparities. LGBT Health 2014, 1, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauckner, C.; Haney, K.; Sesenu, F.; Kershaw, T. Interventions to reduce alcohol use and HIV risk among sexual and gender minority populations: A systematic review. Curr. HIV/AIDS Rep. 2023, 20, 231–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehavot, K.; Johnson, K.E.; Simpson, T.L.; Kaysen, D. Alcohol screening and brief interventions among U.S. veterans who identify as lesbian, gay, or bisexual. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017, 173, 102–108. [Google Scholar]

- United States Preventive Services Task Force. Recommendations. Available online: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/ (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Centers for Disease Control Prevention. Vital signs: Communication between health professionals and their patients about alcohol use—44 states and the District of Columbia, 2011. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2014, 63, 16–22. [Google Scholar]

- Reed, M.B. The effectiveness of brief alcohol interventions in primary care: A real-world study. J. Addict. Res. 2021, 34, 15–24. [Google Scholar]

- Tryggedsson, J.S.J.; Nielsen, A.S.; Nielsen, B. Long-term effectiveness of SBIRT by outreach visits on subsequent alcohol treatment utilization among inpatients from general hospital: A 36-months follow-up. Nord. J. Psychiatry 2024, 78, 736–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, J.; Wang, W.; Zhang, L.; Fu, R.; Zeng, Q.; Huang, L.; Zhao, M.; Du, J. The effect of SBIRT on harmful alcohol consumption in the community health centers of Shanghai, China: A randomized controlled study. Alcohol Alcohol. 2022, 57, 742–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wamsley, M.; Satterfield, J.M.; Curtis, A.; Lundgren, L.; Satre, D.D. Alcohol and drug screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment (SBIRT) training and implementation: Perspectives from 4 health professions. J. Addict. Med. 2018, 12, 262–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galupo, M.P.; Mitchell, R.C.; Davis, K.S. Sexual minority self-identification: Multiple identities and complexity. Psychol. Sex. Orientat. Gend. Divers. 2015, 2, 355–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, I.H. Resilience in the study of minority stress and health of sexual and gender minorities. Psychol. Sex. Orientat. Gend. Divers. 2015, 2, 209–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, I.H. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol. Bull. 2003, 129, 674–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testa, R.J.; Habarth, J.; Peta, J.; Balsam, K.; Bockting, W. Development of the gender minority stress and resilience measure. Psychol. Sex. Orientat. Gend. Divers. 2015, 2, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durso, L.E.; Meyer, I.H. Patterns and predictors of disclosure of sexual orientation to healthcare providers among lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals. Sex. Res. Soc. Policy 2013, 10, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feinstein, B.A.; Dyar, C. Bisexuality and health: New directions in research on identity, stress, and health disparities. Curr. Sex. Health Rep. 2023, 15, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCole, A.R.; Anderson, J.R. “Not queer enough”: A systematic review of the literature exploring experiences of bi-erasure. J. Bisex. 2025, 1–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Center for Health Statistics. National Health Interview Survey, 2022: Public-Use Data File and Documentation; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Hyattsville, MD, USA, 2023. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/documentation/2022-nhis.html (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Janssen, D.S.F. Monosexual/plurisexual: A concise history. J. Homosex. 2024, 71, 1839–1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B.; Lowe, B. An ultra-brief screening scale for anxiety and depression: The PHQ-4. Psychosomatics 2009, 50, 613–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitzer, R.L.; Kroenke, K.; Williams, J.B.W.; Löwe, B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006, 166, 1092–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, P.; Huang, M.; Zhu, H. Association between alcohol drinking frequency and depression among adults in the United States: A cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry 2024, 24, 836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guckel, T.; Prior, K.; Newton, N.C.; Stapinski, L.A. Mediators and moderators in the co-occurring anxiety and alcohol use relationship: Protocol for a systematic review and meta-analysis. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2023, 12, e48875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edelman, E.J.; Tetrault, J.M. Unhealthy alcohol use in primary care—The elephant in the examination room. JAMA Intern. Med. 2019, 179, 9–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeely, J.; Adam, A.; Rotrosen, J.; Wakeman, S.E.; Wilens, T.E.; Kannry, J.; Rosenthal, R.N.; Wahle, A.; Pitts, S.; Farkas, S. Comparison of methods for alcohol and drug screening in primary care clinics. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2110721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coates, D.; Coppleson, D.; Travaglia, J. Factors supporting the implementation of integrated care between physical and mental health services: An integrative review. J. Interprof. Care 2022, 36, 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaacs, A.N.; Mitchell, E.K.L. Mental health integrated care models in primary care and factors that contribute to their effective implementation: A scoping review. Int. J. Ment. Health Syst. 2024, 18, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanhope, V.; Videka, L.; Thorning, H.; McKay, M. Moving toward integrated health: An opportunity for social work. Soc. Work Health Care 2015, 54, 383–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blosnich, J.R. The intersectionality of minority identities and health. In Adult Transgender Care: An Interdisciplinary Approach for Training Mental Health Professionals; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 30–43. [Google Scholar]

- Cyrus, K. Multiple minorities as multiply marginalized: Applying the minority stress theory to LGBTQ people of color. J.Gay Lesbian Ment. Health 2017, 21, 194–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mink, M.D.; Lindley, L.L.; Weinstein, A.A. Stress, stigma, and sexual minority status: The intersectional ecology model of LGBTQ health. J. Gay Lesbian Soc. Serv. 2014, 26, 502–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sattler, F.A.; Zeyen, J. Intersecting identities, minority stress, and mental health problems in different sexual and ethnic groups. Stig. Health 2021, 6, 457–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shangani, S.; Gamarel, K.E.; Ogunbajo, A.; Cai, J.; Operario, D. Intersectional minority stress disparities among sexual minority adults in the USA: The role of race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status. Cult. Health Sex. 2020, 22, 398–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, S.L.; Job, S.A.; Todd, E.; Braun, K. A critical deconstructed quantitative analysis: Sexual and gender minority stress through an intersectional lens. J. Soc. Issues 2020, 76, 859–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dentato, M.P.; Orwat, J.; Austin, A.; Craig, S.L.; Matarese, M.; Weeks, A. Practice Considerations: Use of the SBIRT Model Among Transgender & Nonbinary Populations; Center of Excellence on LGBTQ Behavioral Health Equity: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2022; Available online: https://lgbtqequity.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/SBIRT-TNB-Guidance-2022.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Russett, J.L. Best practices start with screening: A closer look at screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment in adolescent, military, and LGBTQ populations. J. Addict. Offender Couns. 2016, 37, 116–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, M.; Cooper, R.L.; Ramesh, A.; Tabatabai, M.; Arcury, T.A.; Shinn, M.; Im, W.; Juarez, P.; Matthews-Juarez, P. Training to reduce LGBTQ-related bias among medical, nursing, and dental students and providers: A systematic review. BMC Med. Educ. 2019, 19, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjarnadottir, R.I.; Bockting, W.; Trifilio, M.; Dowding, D.W. Assessing sexual orientation and gender identity in home health care: Perceptions and attitudes of nurses. LGBT Health 2019, 6, 409–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, S.I.; Jones, H.R.; Bogen, K.W.; Lorenz, T.K. Barriers experienced by emerging adults in discussing their sexuality with parents and health care providers: A mixed-method study. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2023, 93, 335–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rule, N.O.; Bjornsdottir, R.T.; Tskhay, K.O.; Ambady, N. Subtle perceptions of male sexual orientation influence occupational opportunities. J. Appl. Psychol. 2016, 101, 1687–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Full Sample (N = 2256) | No advice (n = 1150) | Advice (n = 1106) | p-Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Age group (in years) | 0.135 | ||||||

| 18 to 24 | 1061 | 55.3 | 562 | 57.0 | 499 | 53.4 | |

| 25 to 29 | 1195 | 44.7 | 588 | 43.0 | 607 | 46.6 | |

| Race/ethnicity | <0.001 | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 234 | 11.1 | 162 | 15.4 | 72 | 6.4 | |

| Hispanic | 513 | 21.3 | 285 | 23.0 | 228 | 19.5 | |

| Non-Hispanic, other/multiracial | 238 | 9.0 | 129 | 9.6 | 109 | 8.3 | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 1271 | 58.6 | 574 | 52.0 | 697 | 65.8 | |

| Sex | 0.169 | ||||||

| Male | 1107 | 51.1 | 534 | 49.6 | 573 | 52.9 | |

| Female | 1149 | 48.9 | 616 | 50.4 | 533 | 47.1 | |

| Sexual identity | 0.035 | ||||||

| Lesbian or gay | 89 | 3.8 | 33 | 2.5 | 56 | 5.2 | |

| Bisexual | 205 | 9.1 | 103 | 8.8 | 102 | 9.4 | |

| Something else | 53 | 2.4 | 28 | 2.5 | 25 | 2.3 | |

| Straight (not lesbian or gay) | 1909 | 84.7 | 986 | 86.1 | 923 | 83.1 | |

| Marital status | 0.391 | ||||||

| Widowed/divorced/separated | 42 | 1.1 | 22 | 1.3 | 20 | 0.9 | |

| Never married | 1449 | 65.6 | 721 | 64.6 | 728 | 66.8 | |

| Married/member of an unmarried couple | 765 | 33.3 | 407 | 34.1 | 358 | 32.3 | |

| In school | 0.067 | ||||||

| No | 1676 | 71.0 | 822 | 69.2 | 854 | 73.1 | |

| Yes | 580 | 29.0 | 328 | 30.8 | 252 | 26.9 | |

| Region | 0.003 | ||||||

| North Central/Midwest | 530 | 22.6 | 235 | 19.4 | 295 | 26.2 | |

| Northeast | 329 | 17.1 | 170 | 16.7 | 159 | 17.7 | |

| South | 832 | 38.2 | 458 | 42.2 | 374 | 33.7 | |

| West | 565 | 22.1 | 287 | 21.8 | 278 | 22.4 | |

| Educational attainment | <0.001 | ||||||

| Less than high school | 130 | 7.8 | 84 | 10.0 | 46 | 5.3 | |

| Graduated high school or GED | 611 | 30.0 | 335 | 31.5 | 276 | 28.2 | |

| Some college | 777 | 37.4 | 398 | 36.7 | 379 | 38.2 | |

| College graduate | 738 | 24.9 | 333 | 21.8 | 405 | 28.3 | |

| Usual place for medical care | 0.001 | ||||||

| No | 460 | 19.2 | 193 | 16.3 | 267 | 22.3 | |

| Yes | 1796 | 80.8 | 957 | 83.7 | 839 | 77.7 | |

| Insurance status | 0.001 | ||||||

| Private | 1498 | 65.1 | 715 | 61.0 | 783 | 69.6 | |

| Public | 364 | 17.1 | 224 | 20.1 | 140 | 13.9 | |

| Other | 82 | 2.7 | 46 | 2.9 | 36 | 2.6 | |

| Uninsured | 312 | 15.0 | 165 | 16.1 | 147 | 13.8 | |

| Health status | 0.687 | ||||||

| Poor/fair | 138 | 6.0 | 77 | 6.2 | 61 | 5.7 | |

| Good/very good/excellent | 2118 | 94.0 | 1073 | 93.8 | 1045 | 94.3 | |

| General Anxiety Disorder-7 score | 0.007 | ||||||

| None/minimal (0–4) | 1609 | 71.2 | 858 | 74.5 | 751 | 67.6 | |

| Mild (5–9) | 412 | 18.2 | 189 | 16.6 | 223 | 19.9 | |

| Moderate (10–14) | 137 | 5.7 | 62 | 5.2 | 75 | 6.3 | |

| Severe (15–21) | 98 | 4.8 | 41 | 3.6 | 57 | 6.2 | |

| Personal Health Questionnaire-8 score | 0.046 | ||||||

| None/minimal (0–9) | 1609 | 70.9 | 857 | 73.9 | 752 | 67.6 | |

| Mild (10–14) | 408 | 18.7 | 185 | 16.9 | 223 | 20.6 | |

| Moderate (15–19) | 142 | 6.0 | 66 | 5.6 | 76 | 6.4 | |

| Severe (20–24) | 97 | 4.4 | 42 | 3.6 | 55 | 5.3 | |

| aOR | 95% CI | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| LL | UL | ||

| Age group (in years) | |||

| 18 to 24 | 0.80 | 0.64 | 1.00 |

| 25 to 29 | Ref. | ||

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 0.36 | 0.24 | 0.53 |

| Hispanic | 0.76 | 0.59 | 0.99 |

| Non-Hispanic, other/multiracial | 0.70 | 0.50 | 0.98 |

| Non-Hispanic White | Ref. | ||

| Sex | |||

| Female | 0.88 | 0.72 | 1.09 |

| Male | Ref. | ||

| Sexual identity | |||

| Lesbian or gay | 1.81 | 1.03 | 3.18 |

| Bisexual | 0.99 | 0.69 | 1.43 |

| Something else | 0.73 | 0.38 | 1.41 |

| Straight (not lesbian or gay) | Ref. | ||

| Marital status | |||

| Widowed/divorced/separated | 0.87 | 0.43 | 1.74 |

| Never married | 1.30 | 1.05 | 1.61 |

| Married/member of an unmarried couple | Ref. | ||

| In school | |||

| No | 1.21 | 0.96 | 1.54 |

| Yes | Ref. | ||

| Region | |||

| North Central/Midwest | 1.21 | 0.87 | 1.68 |

| Northeast | 1.05 | 0.72 | 1.53 |

| South | 0.84 | 0.63 | 1.13 |

| West | Ref. | ||

| Educational attainment | |||

| Less than high school | 0.48 | 0.29 | 0.78 |

| Graduated high school or GED | 0.78 | 0.58 | 1.05 |

| Some college | 0.94 | 0.73 | 1.21 |

| College graduate | Ref. | ||

| Usual place for medical care | |||

| No | 1.53 | 1.20 | 1.96 |

| Yes | Ref. | ||

| Insurance status | |||

| Private | Ref. | ||

| Public | 0.75 | 0.56 | 1.01 |

| Other | 0.90 | 0.49 | 1.64 |

| Uninsured | 0.93 | 0.68 | 1.27 |

| Health status | |||

| Poor/fair | 0.86 | 0.55 | 1.34 |

| Good/very good/excellent | Ref. | ||

| General Anxiety Disorder-7 score | |||

| None/minimal (0–4) | Ref. | ||

| Mild (5–9) | 1.32 | 0.95 | 1.85 |

| Moderate (10–14) | 1.43 | 0.84 | 2.44 |

| Severe (15–21) | 2.10 | 1.11 | 3.94 |

| Personal Health Questionnaire-8 score | |||

| None/minimal (0–9) | Ref. | ||

| Mild (10–14) | 1.21 | 0.86 | 1.70 |

| Moderate (15–19) | 1.02 | 0.59 | 1.77 |

| Severe (20–24) | 1.04 | 0.52 | 2.10 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Falk, D.S.; Adeleke, C.A.; Macena, M.; Faro, A. Mental Health Symptoms and Alcohol Counseling Among Young Adults: Implications for Equitable Preventive Care. Societies 2025, 15, 335. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15120335

Falk DS, Adeleke CA, Macena M, Faro A. Mental Health Symptoms and Alcohol Counseling Among Young Adults: Implications for Equitable Preventive Care. Societies. 2025; 15(12):335. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15120335

Chicago/Turabian StyleFalk, Derek S., Christian A. Adeleke, Matheus Macena, and André Faro. 2025. "Mental Health Symptoms and Alcohol Counseling Among Young Adults: Implications for Equitable Preventive Care" Societies 15, no. 12: 335. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15120335

APA StyleFalk, D. S., Adeleke, C. A., Macena, M., & Faro, A. (2025). Mental Health Symptoms and Alcohol Counseling Among Young Adults: Implications for Equitable Preventive Care. Societies, 15(12), 335. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15120335