1. Introduction

Migration to Australia occurs through four key pathways: skilled migration, spouse visas, study programmes, and humanitarian entry [

1,

2]. In recent years, skilled migration has emerged as a dominant stream, positioning Australia as a hub for globally mobile professionals seeking career advancement and international recognition. This appeal is further strengthened by Australia’s promotion of multiculturalism and anti-discrimination policies, which project an inclusive and equitable national ethos [

2,

3]. Despite these formal commitments, a disjunction persists between policy rhetoric and lived realities. While organisations annually observe anti-discrimination campaigns such as Respect Month and the Positive Duty Oration Day, African migrant professionals continue to face subtle and layered exclusions in Australian workplaces. These professionals are first-generation skilled migrants from diverse African countries—highly educated individuals employed across sectors such as health, education, engineering, finance, and community services. These exclusions are not only enacted by dominant cultural groups but also emerge from within multicultural networks and fellow migrant communities [

4,

5,

6].

National frameworks such as the Australian Human Rights Commission’s Anti-Racism Strategy [

7] primarily address broad social inequities, often neglecting the specific, intersecting power dynamics experienced within professional settings. This disconnect reflects a gap between symbolic commitment to diversity and the deeper structural and interpersonal dynamics that shape migrant workplace experiences.

This paper critically examines the concept of “layered exclusions,” where exclusion operates simultaneously across various levels of the professional environment—from dominant groups, other migrant communities, and within migrants’ own ethnic or professional networks. It aims to provide new insights into the structural and cultural barriers impeding genuine inclusion and to assess how policy can better respond to these complexities. In doing so, this study contributes to scholarly debates on multiculturalism, migrant integration, and workplace equity by centring the nuanced lived experiences of African professionals in Australia.

While an expanding body of literature has addressed migrant integration and workplace discrimination, few studies have examined how exclusionary practices operate within multicultural professional environments. Ostrand [

8] outlines systemic discrimination across diverse settings but stops short of addressing internal group tensions. Salikutluk [

9] and Schweitzer [

10] acknowledge multicultural complexity but fall short of analysing how layered and intersecting exclusions play out within intra-migrant and inter-professional dynamics. Meanwhile, Scuzzarello [

11] and Wang et al. [

12] focus on identity and hierarchy in non-Australian contexts, limiting their applicability.

In Australia, much research has centred on host-migrant binaries, largely overlooking how inter-migrant dynamics and symbolic capital shape professional exclusion. The unique interplay of ethnicity, legal status, skill level, and cultural proximity to dominant norms has not been adequately explored. This study addresses this void by investigating how African professionals experience and navigate exclusion from multiple sources simultaneously.

The next section outlines the statement of the problem and the theoretical and conceptual framework, drawing on Intersectionality, Social Dominance Theory, and Bourdieu’s concepts of capital and habitus, as well as the research questions that guided the study. This is followed by the methodology, which details the research design, participant demographics, and data collection methods. The findings section presents key themes emerging from participants’ narratives of layered exclusions. The discussion then situates these findings within broader debates on multiculturalism and workplace equity, while the conclusion highlights implications for policy, practice, and future research.

2. Statement of the Problem

Australia’s commitment to multiculturalism has largely been conceptualised through a majority-minority lens, often assuming that shared migrant status leads to mutual support. However, African migrant professionals often confront a more complex terrain, experiencing exclusion not only from dominant workplace cultures but also from fellow migrants and within their own ethnic and professional communities. These forms of exclusion—what we define as “layered exclusions”—challenge the prevailing assumption that multicultural workplaces inherently foster inclusion.

This study conceptualises layered exclusions as intersecting and cumulative barriers that undermine professional belonging. These may include status policing, subtle gatekeeping, and differential recognition of cultural capital. The failure of current diversity frameworks to account for these dynamics constitutes a major gap in migration scholarship and workplace policy. This paper investigates how these dynamics unfold and how they shape African professionals’ access to power, opportunity, and recognition.

3. Theoretical Framework

This study is underpinned by a multi-theoretical framework that integrates Intersectionality Theory [

13], Social Dominance Theory [

14], and Bourdieu’s [

15,

16] concepts of cultural capital and habitus. Each of these frameworks has been widely applied in migration and diversity scholarship, yet their combined use offers a novel lens for examining layered forms of exclusion and intra-group power dynamics in multicultural workplace contexts.

This framework builds on, but moves beyond, prior work by migration scholars such as Ostrand [

8], Scuzzarello [

9], and Schweitzer [

17,

18], whose studies have largely focused on majority–minority power relations or systemic discrimination by host societies. However, few have explored inter-migrant discrimination—the often subtle, underexamined power imbalances and gatekeeping practices that arise among migrant groups themselves, particularly in settings like Australia where multiculturalism is both a policy and workplace norm.

Intersectionality Theory offers a critical lens to examine how overlapping identity markers—such as ethnicity, legal status, migration pathway, and professional background—intersect to shape differentiated experiences of privilege and marginalisation. This is especially relevant in contexts where solidarity based on shared migrant status is assumed but not always realised in practice.

Social Dominance Theory (SDT) enhances this analysis by unpacking how social hierarchies are maintained even within marginalised groups. It helps explain how more established migrants may assert dominance over newer or differently positioned peers through informal mechanisms like status policing, language privilege, or alignment with host cultural norms.

Bourdieu’s concepts of cultural capital, symbolic power, and habitus further illuminate how legitimacy and recognition are differentially distributed in professional spaces. For instance, migrants with Western-accredited qualifications or fluency in Australian workplace culture may be seen as more credible, marginalising others despite comparable skills or achievements.

While each framework has limitations—Intersectionality can be expansive and complex to operationalise; SDT risks reinforcing static group categories; and Bourdieu’s tools can be conceptually dense—their integration enables a more dynamic, context-sensitive analysis of workplace inequality.

This triangulated framework enables the study to capture the structural (SDT), identity-based (Intersectionality), and cultural-symbolic (Bourdieu) dimensions of exclusion. It responds to a critical gap in migration research by offering a theoretically grounded, empirically informed analysis of inter-migrant power relations—a phenomenon often overshadowed in studies of multiculturalism and workplace integration. As such, the framework advances current theoretical debates while providing analytical tools for understanding the multi-layered nature of exclusion in diverse professional settings.

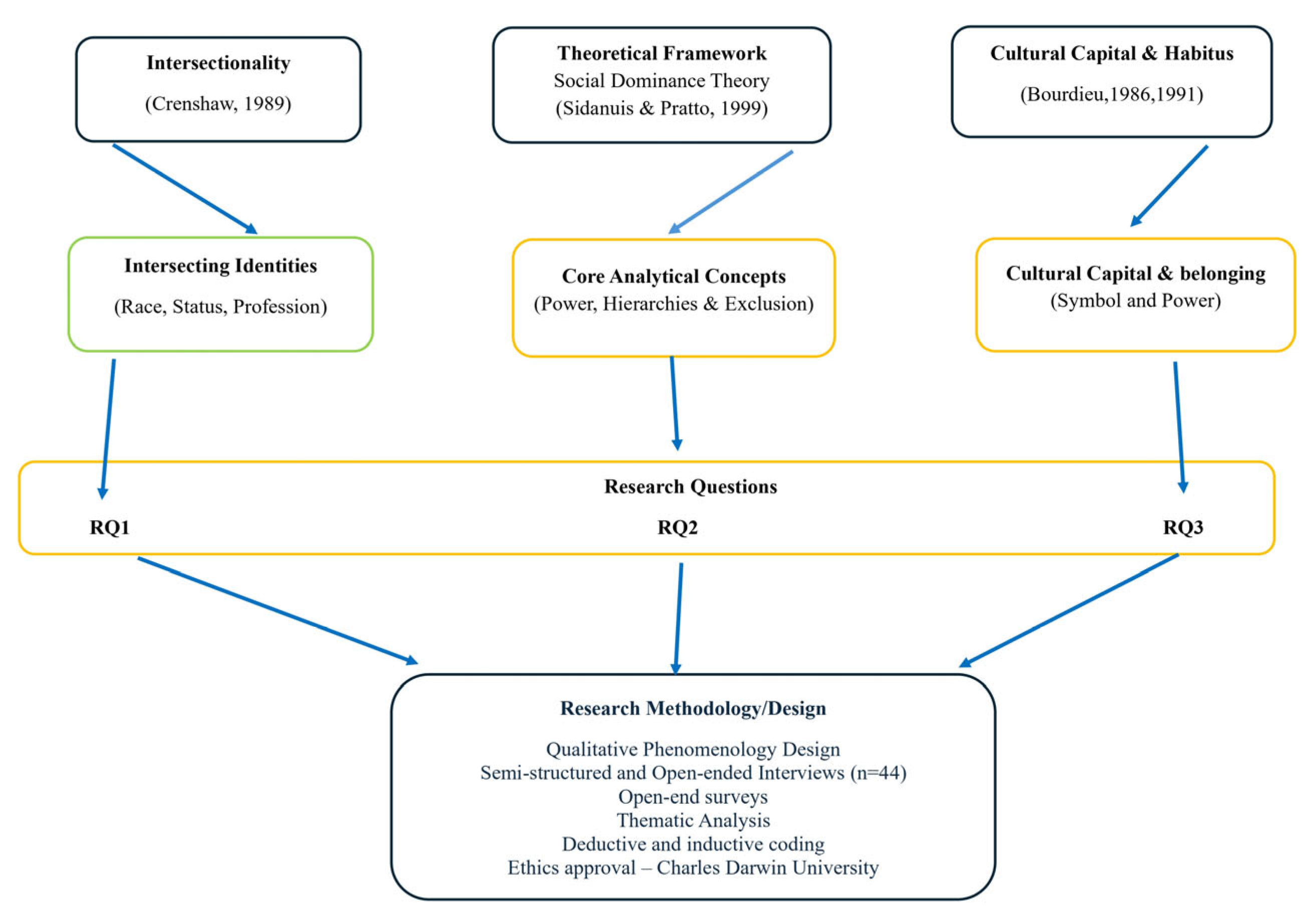

4. Conceptual Framework

As stated in

Figure 1, this study’s conceptual framework integrates key analytical constructs to explore how African migrant professionals experience and navigate exclusion within Australian workplaces. It draws on the interplay of identity, power, and professional belonging to understand the complex, layered nature of marginalisation. Central to the framework is the notion that individuals do not experience workplace dynamics through a single lens. Instead, overlapping aspects of identity—such as race, migration status, language proficiency, and educational background—interact to influence how these professionals are perceived and treated in professional settings. Guided by principles from Intersectionality Theory, this approach foregrounds how such identity intersections shape differentiated access to opportunity and recognition.

Alongside identity, the framework attends to the often subtle but persistent ways power hierarchies’ structure professional interactions. These hierarchies, informed by Social Dominance Theory, are embedded in workplace norms and expectations related to assimilation, cultural fluency, and perceived merit. Gatekeeping occurs through informal yet powerful mechanisms that can restrict African professionals’ participation, limit their progression, or question their competence. These dynamics are particularly potent in environments that promote multiculturalism on the surface but retain deeply embedded institutional biases.

Importantly, exclusion is not solely enacted by dominant cultural groups. The framework recognises that exclusion may also arise from within broader migrant networks and professional peer groups. Through the lens of Bourdieu’s concepts of cultural capital and habitus, the study examines how symbolic resources—such as recognised qualifications, manner of speech, and professional etiquette—shape perceptions of legitimacy. Migrants who lack locally valued forms of capital may be marginalised not only by mainstream institutions but also within intra-group or co-ethnic professional spaces.

This framework also considers how African professionals respond to these forms of exclusion. Rather than focusing solely on disadvantage, it explores agency and adaptability—how individuals resist marginalisation, navigate structural constraints, and cultivate new forms of belonging. These responses may include the strategic acquisition of valued capital, the reassertion of identity, or the development of alternative pathways to recognition and legitimacy. In doing so, the framework captures both the constraints imposed by institutional power and the resourcefulness of individuals working to sustain their professional identity and psychological wellbeing.

By connecting identity, power, exclusion, and adaptation in a coherent structure, this conceptual framework informs the study’s methodological choices, thematic focus, and research questions. It supports a phenomenological inquiry that is grounded in the lived realities of African professionals and sensitive to the social, structural, and symbolic conditions shaping their everyday work lives.

5. Research Questions

How do African migrant professionals experience and navigate layered forms of workplace exclusion in Australian professional environments?

What role do intersecting identities (race, gender, migration status, and professional qualifications) play in shaping workplace experiences for African professionals in Australia?

How do African migrant professionals resist, adapt to, and challenge subtle workplace marginalisation while maintaining their professional identity and psychological wellbeing?

These questions enabled the researchers to gain the needed understanding of the lived experiences, underlying causes, and professional impacts of inter-migrant discrimination among African migrant professionals in Australian workplaces.

6. Significance of the Study

This study brings attention to a neglected aspect of workplace diversity: the layered forms of exclusion African migrant professionals face within multicultural work settings. While most research highlights disparities between dominant and minority groups, this study explores how exclusion also occurs within migrant networks and professional communities. It examines how overlapping factors—such as race, migration status, language, and cultural capital—shape experiences of belonging, recognition, and advancement. By drawing on Intersectionality Theory, Social Dominance Theory, and Bourdieu’s concepts of capital and symbolic power, the study offers a lens to understand how informal gatekeeping and unspoken norms can undermine inclusion, even in settings that promote multicultural values.

Based on the experiences of 44 African professionals in Australia, the findings challenge the assumption that diversity automatically leads to solidarity or fairness. Instead, they show how subtle power dynamics can reinforce exclusion at multiple levels. This research speaks directly to ongoing efforts to create fairer and more inclusive workplaces. It calls for more nuanced approaches that recognise the complexity of identity, power, and belonging in migrant professionals’ lives, and urges institutions to look beyond surface-level diversity metrics to address the deeper structures that shape inclusion.

7. Research Design

This study employed a qualitative, phenomenological design to explore how African migrant professionals in Australia experience layered forms of workplace exclusion. Phenomenology was selected for its emphasis on lived experience and its capacity to illuminate how participants interpret and make sense of complex interactions within professional environments [

13,

19]. The approach is particularly suited to capturing the nuanced and subjective ways in which exclusion is encountered, negotiated, and understood across diverse workplace contexts.

A total of 44 participants were recruited through professional networks, community-based organisations, targeted email invitations, and snowball referrals. This multi-pronged recruitment strategy ensured the inclusion of a diverse cross-section of African professionals with varying migration pathways, legal statuses, genders, and career stages. Data collection combined open-ended surveys with semi-structured interviews, providing both breadth and depth in understanding participants’ perceptions of exclusion, power relations, and belonging.

Interview prompts were grounded in the study’s integrated conceptual framework, which combines Intersectionality Theory [

13,

20], Social Dominance Theory [

14], and Bourdieu’s concepts of capital and habitus [

13,

15]. This framework directed attention to the intersections of identity—such as race, migration history, professional standing—as well as to workplace hierarchies, informal norms, and symbolic markers of legitimacy.

7.1. Data Analysis

Data were analysed thematically using NVivo 12 software. A hybrid coding strategy was employed: deductive codes were derived from the conceptual framework (e.g., symbolic power, assimilation, layered exclusions), while inductive codes emerged directly from participants’ accounts. Beyond the coding process, survey data provided quantitative context—for example, demographic distributions (gender balance, years of residence, visa status)—which authenticated the representativeness of the sample. Interview data, by contrast, provided qualitative depth, capturing lived experiences and interpretations. The two data sources were integrated by using survey demographics to frame and contextualise the thematic narratives emerging from interviews, ensuring that the analysis was both empirically grounded and theoretically informed [

21].

7.2. Researcher Positionality and Reflexivity

All authors identify as African scholars, bringing insider perspectives to the research context. This positionality facilitated insider access to professional and community networks and enhanced rapport with participants. At the same time, we recognised the risk of interpretive bias. To mitigate this, we engaged in ongoing reflexivity, keeping analytic memos throughout the research process [

22], and conducted peer debriefing among the author team to interrogate assumptions and alternative interpretations.

Additionally, member checking was undertaken by sharing emerging themes with a subset of participants to confirm accuracy and resonance with their lived experiences [

23]. These steps ensured that findings were grounded in participants’ voices and not influenced by researchers’ prior assumptions. Together, reflexivity, triangulation of methods, and member validation enhanced the credibility and trustworthiness of the study.

7.3. Ethical Consideration

Ethical approval for this study was granted by Charles Darwin University, Northern Territory. All participants provided informed consent, and strict measures were taken to ensure confidentiality and anonymity.

7.4. Participant Demographics and Recruitment

This study draws on 44 African migrant professionals working in Australia across health, education, allied health, and community service sectors. Participants were recruited through professional networks, community associations, targeted email invitations, and snowball referrals. This strategy ensured the inclusion of a broad cross-section of African professionals with varying migration pathways, legal statuses, and career stages. Participation was voluntary, and informed consent was obtained from all respondents.

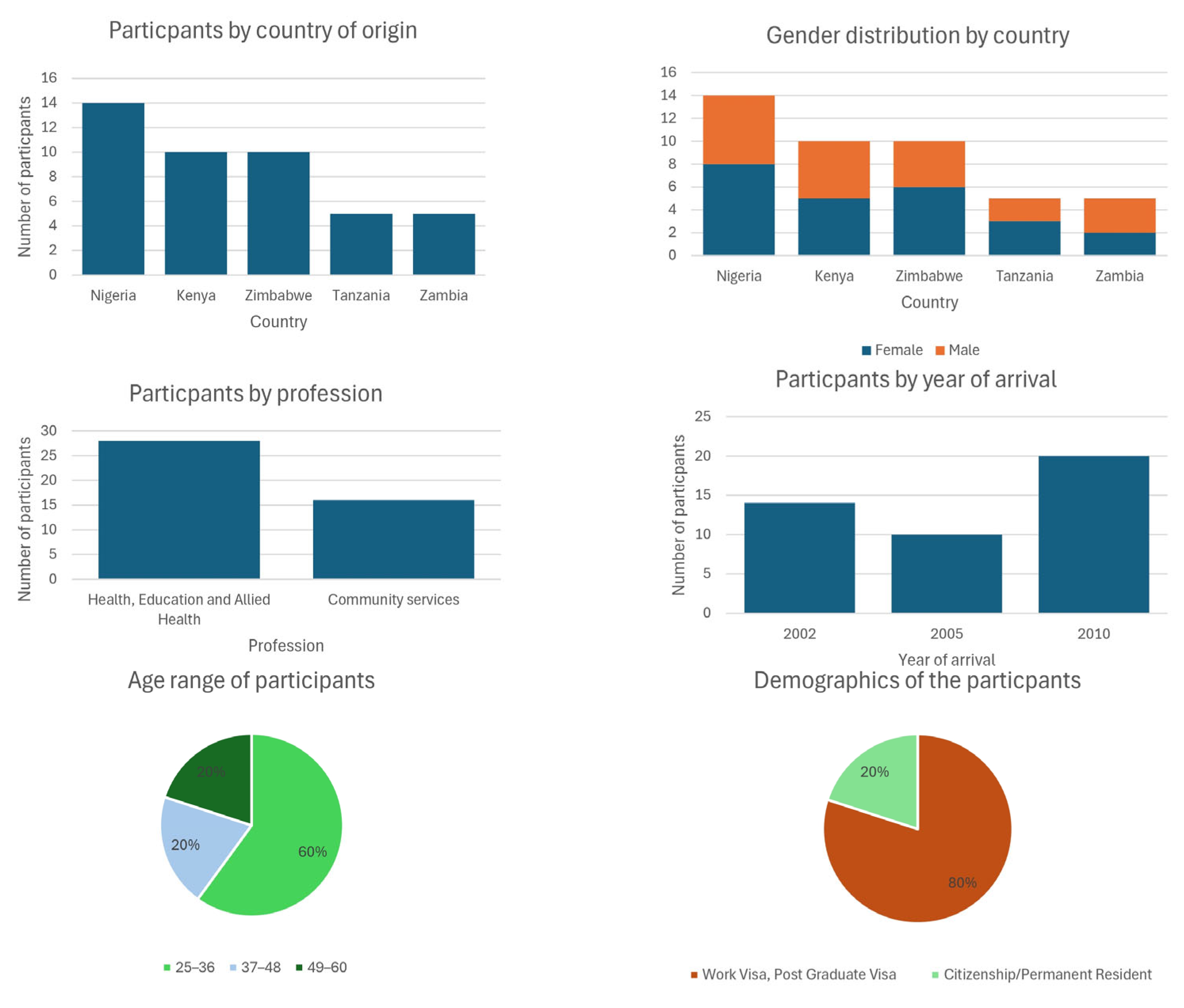

The demographic profile reflects both diversity and representativeness in relation to the study’s focus on intersectionality. National groups included Nigerian (n = 14), Kenyan (n = 10), Zimbabwean (n = 10), Tanzanian (n = 5), and Zambian (n = 5) professionals, most of whom were employed in skilled professions within education, health, and community services. Participants ranged in age from 25 to 60 years, with both younger early-career professionals and established mid- to late-career migrants represented. Gender distribution was relatively balanced (25 females and 19 males), although there were slight variations across national groups.

Years of residence in Australia ranged from 2002 to 2024, capturing both early skilled migrants and recent entrants. Visa status included temporary work visas, postgraduate student visas, permanent residency, and full Australian citizenship. This diversity is particularly significant within the intersectionality framework, as it highlights how legal status intersects with race, gender, and profession to shape access to opportunity and belonging.

Table 1 presents the demographic profile of the participants, disaggregated by country of origin, profession type, age, gender, years of residence, and visa status.

Figure 1 complements this table by providing a visual summary of these characteristics, illustrating variation across nationality, gender, age, professional background, settlement history, and visa categories. Together,

Table 1 and

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 demonstrate the diversity of the participant group and authenticate the study’s intersectional approach to analysing layered workplace exclusions.

8. Data Analysis and Findings

Building on the demographic profile presented in

Table 1 and

Figure 1, this section presents the key themes that emerged from the study. The analysis draws on 44 semi-structured interviews and survey data, situated within the integrated theoretical framework of Intersectionality Theory [

20], Social Dominance Theory [

14], and Bourdieu’s concepts of cultural capital and habitus [

15].

The findings illustrate how subtle exclusion, power struggles, and claims to legitimacy are negotiated not only between dominant and minority groups but also within migrant communities themselves. While much scholarly and policy attention has focused on majority–minority dynamics, the data reveal that layered exclusions represent a significant yet often overlooked force shaping professional belonging, access to opportunity, and workplace hierarchies. From this analysis, six key themes emerged, each shedding light on the structural and cultural barriers that African migrant professionals confront in their pursuit of workplace equity.

8.1. Subtle Exclusion and Professional Gatekeeping by Fellow Migrants

Participants consistently identified subtle exclusion as a defining feature of their workplace experiences. This exclusion was not only enacted by dominant cultural groups but also by fellow migrants—particularly those perceived as more assimilated or professionally entrenched. A recurring form of exclusion involved professional gatekeeping, where migrant colleagues deliberately withheld or controlled access to workplace knowledge, thereby limiting opportunities for African professionals to progress.

Survey data reinforced these accounts: 55.77% of participants reported experiencing microaggressions “occasionally” to “constantly,” many of which involved lateral discrimination from other migrant colleagues. One participant reflected:

I once worked somewhere and one of my colleagues who was Indian was instructed by the supervisor to induct me… he intentionally did not show me a lot of things because he wanted me to make mistakes… he wanted his fellow Indian brother instead of me.

(WA Participant)

Such exclusion also undermined professional legitimacy. For example, one nurse described how patients responded differently depending on the ethnicity of staff:

Patients will question us about medication, but when a non-African nurse arrives, they just comply. It’s hard not to see that as racial. We’re at the bottom of the chart.

(WA Participant)

Leadership opportunities were also affected, with African professionals frequently required to “prove” competence even when their credentials were sufficient:

For Africans to be fully accepted into leadership role without they proving they are capable. Even if the resume says they can, it is viewed with a second look.

(NT Participant)

Additional survey data highlighted how hierarchies operated not only between migrants and dominant groups but also within migrant communities:

At times ones (sic) colour is just the main issue. Asians should be educated more on this, especially Indians…. Usually, Australians prefer working with each other rather than with migrants. Doesn’t mean they’re racist but just natural human behaviour.

(VIC Participant)

These findings show how professional proximity to dominant norms—such as whiteness, fluency, or seniority—enabled subtle but impactful gatekeeping among migrants themselves. This exclusion cut across healthcare, education, allied health and community services and highlighting its systemic character.

8.2. Performing to Belong: Overcompensation as a Strategy of Survival

Majority of the participants also reported a constant need to overperform in order to be seen as legitimate in their roles. This overcompensation was often a reaction to deficit assumptions and racial stereotypes that cast African professionals as less capable. The thoughts of the two participants reported below captures the feelings of other 42 African professionals interviewed in this study across states and territories.

Survey data confirmed this pressure: only 37.3% of participants felt their achievements were recognised “to a large extent” or “completely.” The majority described having to continually prove themselves. As one participant explained:

Sometimes because of your skin colour, people underrate you until you prove yourself with your skills and creativity…. I have to consistently put in efforts to prove my skills and that I can be trusted.

(QLD, NSW, VIC Participants)

This overperformance functioned as both a defensive mechanism and a coping strategy, but it came at significant emotional cost. One participant noted:

Managing such challenges is hard… I try to push through… I just learn to focus on my task and make sure I do my job effectively.

(NT Participant)

Others described the burden of always having to exceed expectations:

Very sketchy at the start until you prove yourself for the position you are occupying…. To do your best and show that your (sic) are overqualified for your roles…. Many doubted my ability to deliver but with tenacity, perseverance and resilience, I’m still climbing to the peak of my career.

(NSW Participant)

The psychological toll was also evident:

The drive to achieve excellence and acceptance in the society and the need for financial stability…. I just do my job to the back of my ability and let it speak for me.

(VIC Participant)

The survey revealed that 47.06% of participants rated their sense of belongingness as moderate, suggesting that even sustained overperformance often results in only conditional acceptance rather than full inclusion.

8.3. Cultural Capital Mismatch and the Devaluation of African Credentials

A recurring theme was the devaluation of African-acquired qualifications and experience. Many participants reported barriers such as re-certification requirements, mandatory language tests, or outright dismissal of their credentials.

Most Australians only recognise people who have gone through their education system… else you can only work on jobs Australians dislike. There are too many hurdles… ranging from eligibility to professional exams and English language exams.

(WA Participant)

The findings also revealed the comprehensive nature of these barriers. One participant detailed their experience:

As a professional migrant in Australia, I observed that there was no room or support for me to continue my career in my profession. There are too many hurdles to practicing my profession in Australia. Ranging from eligibility to professional exams and English language exams which I am required to satisfy before joining my profession in Australia.

(NSW Participant)

This mismatch often relegated African professionals to lower-status or unrelated jobs.

There are too many hurdles… ranging from eligibility to professional exams and English language exams.

(Participant, NT)

I’ve changed professions a couple of times just to keep myself sane and marketable professionally. I have tried to offer my Nigerian training as a teacher in some Australian schools, but the wages are evidence that I’m not an Australian-trained school staff.

(WA Participant)

Survey evidence highlighted professional underemployment and career disruption, with participants emphasising that recognition of African qualifications would significantly improve integration. Barriers such as accent, cultural differences, and employer reluctance further entrenched exclusion.

Participants identified specific systemic barriers including “accent differences and language barrier” and “Cultural differences and the lack of information on education and work experience of African migrants. Reluctance or non-acceptance of credentials and experiences of migrants.”

Two participants captured discrimination in hiring practices:

I felt excluded when I was discriminated against… after the completion of my study mainly due to my cultural background and the unwillingness of some employers to give migrants from CALD background a fair go.

(NT, QLD Participants)

8.4. Identity Policing and the Weight of Acceptable Diversity’

Participants noted that belonging in Australian workplaces was often conditional, dependent on conforming to narrow versions of diversity. Survey data reflected this: only 39.22% of participants felt their cultural background was valued “to a large extent” or “completely.” As one participant commented:

I felt included when my workplace needed a show of multiculturalism. (NT Participant)

Others noted the emotional toll of performing diversity without genuine recognition:

Just not resonating with some of the practices and celebrations they do in the workplace in the name of promoting diversity. When I had a baby, no one contacted me… but I was always asked to contribute money or gifts for other workmates who were pregnant.

(NT Participant)

Tokenism was also evident in cultural representation:

I have been asked several times to share my culture through my dressing or food. They divert to my expertise and seek my opinion when discussing African issues. We have slots available to tell colleagues about some important dates per their background. Like Independence Day or Christmas or Africa Union Day etc…There was a project where my team organized a cultural exchange event to celebrate diversity… I felt genuinely included and valued during this event.

(WA Participant)

These accounts reveal how workplaces often frame diversity for optics rather than inclusion, leaving African professionals valued more for symbolic representation than for their expertise. Survey evidence shows participants being valued primarily for their ability to represent diversity in visible, non-threatening ways “Being part of harmony day celebration. The day I won the best dressed in a community women’s day celebration”.(NSW Participant)

8.5. Silence, Isolation, and the Emotional Labour of Inclusion

The emotional toll of exclusion was significant. Many participants described coping strategies such as silence, self-isolation, and emotional suppression—ways to survive without risking professional standing.

I felt like I had to protect myself from exclusion by not putting myself out there…. over time, we have developed a thick skin and tend to ignore some of these things.

(WA Participant)

The survey data revealed the widespread nature of these coping mechanisms:

Over the time we have developed a thick skin and tend to ignore some of these things… our level of resilience increased…To be tough, thicker skin to subtle racist slurs can help you get through the day. Not to be overwhelmed and remain in your best self…I just do my work and not listen to toll.

(NT, WA, QLD, NSW, VIC Participants)

Survey evidence supported this pattern, showing widespread reliance on resilience and avoidance:

I decided not to cope with or deal with any emotional challenges… I address any issues… by speaking with the perpetrator in private.

(TAS Participant)

The survey provided extensive evidence of protective strategies:

So far I haven’t really felt excluded and it’s probably because most of the time I felt like I had to protect myself from any sort of exclusion by not putting myself out there.

(TAS Participant)

Minding my business and staying focused. I ignore it and keep leaning in. Managing such challenges is hard most of the time but I just try to push through and brush it off.

(NSW Participant)

Support systems such as faith, family, and African community networks also emerged as protective strategies

Self-love. Reinforcing in my mind that there is nothing wrong with me… My faith as a Christian. My family and my African community. Family, friends and communication with people in similar situations in diaspora… Taking long walks and venting /talking to my fellow nurses of the same skin colour.

(NSW, VIC, WA, NT, TAS Participants)

These strategies reflect Bourdieu’s concept of habitus, with participants adapting behaviours to survive exclusionary environments. Emotional labour became a necessary cost of professional survival.

8.6. Intra-Community Tensions and Internalised Hierarchies

The most unexpected theme that emerged was tension and discrimination within African migrant communities themselves. Participants described discriminatory or exclusionary behaviour from other migrants, including those of African descent. These intra-community tensions often complicated the assumption of solidarity within migrant groups.

One participant shared:

She said I wasn’t what she needed—she wanted someone white, someone Australian. The irony was that she was a migrant too. In that moment, my race wasn’t just questioned—it became a tool used to erase my humanity and dismiss my professional worth.

(Participant, WA)

The survey data revealed additional dimensions of intra-community challenges. Other participants expressed similar scenarios that clearly showed how gender played a role in intra-community dynamics:

I am facing a lot of challenges within the African Community and am unable to address them because of my gender as a single woman.

(Participant, ACT)

Other participants described imported political and cultural divisions:

The worst-case scenario is the politics from back home many Africans are practising in Australian society with their Chinese counterparts. I have no clue as to how to overcome those problems.

(WA Participant)

Cross-cultural tensions were equally evident, with African professionals excluded by other migrant groups:

I ones worked somewhere and one of my colleagues who was and Indian was instructed by the supervisor to induct me and the guy intentionally did not show me a lot of things because he wanted me to make mistakes. The reason is because he wanted his fellow Indian brother instead of me.

(WA Participant)

These accounts reveal how migrants may reproduce dominant hierarchies to assert professional legitimacy. Intersectionality and Social Dominance Theory help explain how power and exclusion operate within and between migrant groups, not just between dominant and minority populations.

Synthesis of Findings

These six themes reveal the layered and often contradictory dynamics that shape the workplace experiences of African migrant professionals in Australia. Subtle exclusion and professional gatekeeping (Theme 1), the pressure to overperform (Theme 2), and the devaluation of African-acquired credentials (Theme 3) demonstrate how systemic barriers limit professional legitimacy and mobility. At the same time, identity policing (Theme 4), the emotional labour of silence and isolation (Theme 5), and intra-community tensions (Theme 6) highlight the psychological, social, and relational costs of navigating these exclusionary environments. The integration of survey evidence and interview narratives confirms that these patterns cut across sectors, states, and years of residence, underscoring their structural rather than incidental nature. Importantly, the findings challenge binary framings of inclusion as a dominant–minority issue, showing instead that exclusion is reproduced within and between migrant groups. This complexity calls for diversity and equity frameworks that move beyond symbolic inclusion toward a deeper engagement with the relational and intersectional realities of migrant professional life.

9. Discussion

The findings illuminate a critical dimension of workplace discrimination that warrants deeper scholarly attention: the complex dynamics of exclusion and gatekeeping that African professionals face in multicultural workplaces. Participants’ narratives demonstrate that layered workplace exclusions originate from multiple sources—dominant cultural groups, other migrant communities, and even co-ethnic peers. This concept explains

where exclusion comes from and the different levels at which it operates. In contrast, intersectionality highlights

how identity markers—such as race, gender, class, visa status, and professional position—interact to intensify disadvantage or privilege [

20]. Put simply, layered exclusion addresses the origins of exclusion, whereas intersectionality captures the compounding effects of multiple identities. Distinguishing between these two dynamics enables a more nuanced understanding of both the structural locations and lived complexities of exclusion.

Our findings expand existing scholarship on workplace discrimination [

9,

10,

11] by showing how symbolic boundaries and hierarchies operate

within multicultural teams, challenging simplified majority–minority binaries. Participants’ accounts revealed that exclusion was enacted through subtle gatekeeping practices, credential devaluation, identity policing, emotional labour, and intra-community tensions, underscoring that multicultural workplaces do not automatically guarantee inclusion.

The integration of our three theoretical frameworks—Intersectionality Theory, Social Dominance Theory, and Bourdieu’s concepts of capital and habitus—provides a more comprehensive understanding of these dynamics than any single framework could offer. Social Dominance Theory [

14] explains the persistence of group-based hierarchies, including how dominant and migrant groups maintain their advantage through legitimising myths and everyday practices. Yet, it cannot account for how intersecting identities create unique vulnerabilities. Intersectionality fills this gap, illustrating, for example, how African women on temporary visas experienced distinct forms of exclusion compared with African men with permanent residency [

24]. Bourdieu’s concepts of cultural capital and habitus [

15] further illuminate why African-acquired credentials were routinely devalued: professional legitimacy was tied to forms of capital recognised within Australian institutions, privileging local over foreign qualifications. When combined, these frameworks reveal not just the mechanisms of discrimination but also their symbolic and relational dimensions [

25,

26].

Although Australia positions itself as a multicultural society with robust anti-discrimination frameworks [

4,

7], our findings align with critiques that such policies often fail to address the micro-political tensions that professionals face daily [

5,

6]. More recent analyses [

24,

26] confirm this gap between policy rhetoric and lived realities, showing that the persistence of layered exclusions disrupts assumptions that multicultural environments automatically foster inclusion. Instead, assimilation, professional status, and perceived legitimacy produce complex hierarchies where exclusion emerges not only from dominant cultural groups but also from migrants competing for recognition.

These findings also resonate with global patterns. A study [

27] reveals that migrant professionals in diverse contexts experience lateral discrimination and stratification, with proximity to whiteness and Western institutional norms functioning as valuable forms of social capital. Yet, the Australian case reflects its own historical and political specificities. Legacies of colonisation, geographic location in the Asia-Pacific, and immigration policies create distinctive dynamics that shape how African professionals are positioned compared with their counterparts in Europe or North America [

28,

29].

The theme of subtle exclusion and gatekeeping illustrates how power manifests informally through selective language use, withholding workplace knowledge, or privileging certain groups. This supports [

14] argument in Social Dominance Theory that hierarchies are reproduced through everyday interactions as much as through formal structures. Consistent with [

30,

31], participants described how those without fluency in dominant cultural scripts or visible proximity to whiteness were particularly vulnerable to exclusion, undermining narratives of multicultural cohesion.

Other findings highlighted the emotional labour of survival. African professionals reported patterns of overcompensation and self-regulation as strategies to gain legitimacy, reflecting [

15] notion of symbolic capital. This constant burden of proving competence echoes [

32] work on “double consciousness,” where African professionals must simultaneously manage external perceptions and intra-community expectations. The devaluation of African-acquired credentials further entrenched marginalisation, aligning with [

16] argument that cultural capital only has value when recognised by institutional gatekeepers. These findings parallel research across the Asia-Pacific [

32] showing how qualification recognition remains unevenly distributed, often disadvantaging professionals from African and other CALD backgrounds [

33,

34].

The theme of identity policing and ‘acceptable diversity’ revealed the symbolic nature of multicultural inclusion, where diversity is celebrated for optics rather than structural integration [

5,

11,

33]. Participants described being asked to represent cultural difference—through food, dress, or cultural events—while their expertise was undervalued, leaving them hyper-visible as symbols of diversity but marginalised as professionals. Similarly, the themes of silence, isolation, and emotional regulation reflect how habitus shapes behaviour in exclusionary environments, forcing individuals to adapt to survive while carrying psychological costs [

6,

27].

Perhaps most significantly, the theme of intra-community tensions challenges the assumption that shared racial or cultural identity guarantees solidarity. Instead, participants reported exclusionary behaviour from other migrants, including Africans, who reproduced dominant hierarchies to secure their own proximity to privilege. These dynamics reflect what Schweitzer [

18] and Salikutluk [

9] describe as stratification within migrant groups, where internalised hierarchies mirror broader social inequalities. Here, intersectionality again proves critical: gender, migration status, and class intersected with ethnicity to shape divergent experiences of exclusion [

25,

35].

These findings complicate binary models of inclusion and exclusion by exposing how power circulates across different levels and sources. They show that exclusion is not merely top-down from dominant to minority groups but is reproduced horizontally within migrant communities themselves. This confirms recent work by [

24] on hierarchies of acceptability, where assimilation and professional legitimacy operate as social currencies in competitive labour markets.

While the study highlights enduring structures of exclusion, it also reveals African professionals’ agency and resistance. Participants described strategic code-switching, creating informal support networks, and invoking diversity policies to challenge discriminatory practices. These strategies align with Kwansah-Aidoo and Mapedzahama’s [

32] notion of “strategic resistance,” demonstrating that African professionals are not passive victims but active agents reshaping workplace power dynamics.

In summary, this study contributes to migration and workplace diversity scholarship by clarifying the distinction between layered exclusion (origins of exclusion) and intersectionality (compounding identities), while situating both within the wider frameworks of Social Dominance Theory and Bourdieu’s capital and habitus. By applying this multi-theoretical lens, it reveals how exclusion in multicultural workplaces is simultaneously structural, symbolic, and relational. The findings suggest that genuine inclusion requires moving beyond symbolic multiculturalism toward policies that recognise the complex, multi-sourced, and intersectional nature of exclusion [

24,

29].

10. Conclusions and Recommendations

This study illuminates the complex nature of workplace discrimination experienced by African migrant professionals in Australia, with particular emphasis on the under-researched phenomenon of layered workplace exclusions. The narratives presented challenge conventional assumptions of solidarity within multicultural environments and demonstrate how assimilation, symbolic capital, and perceived legitimacy function as tools of both inclusion and exclusion across different levels and sources. These findings reveal significant limitations in existing diversity and inclusion strategies that primarily focus on binary power models, often overlooking the nuanced, intersecting dynamics that profoundly shape workplace belonging and professional advancement.

The experiences shared by participants demonstrate that discrimination exists not only along majority–minority lines but also within the intricate relational dynamics across different groups in multicultural professional environments. This understanding demands a fundamental reconsideration of how workplace inclusion is conceptualised, measured, and implemented in increasingly diverse professional environments [

2,

26,

28]. Genuine inclusion requires addressing not only explicit discrimination but also the subtle ways in which power operates through professional legitimacy, cultural capital, and assimilation pressures across different levels.

Implementing these changes will inevitably face challenges. Organisational resistance may stem from limited resources, competing priorities, or a lack of understanding about layered workplace exclusions. Some diversity initiatives may resist expanding their focus beyond majority–minority dynamics, viewing complex intra-group tensions as secondary concerns. Additionally, addressing these issues requires confronting uncomfortable realities about how privilege operates within marginalised communities themselves. As Hiruy and Hutton [

29] observe, there can be resistance from migrant groups who have achieved relative privilege and may perceive changes to existing hierarchies as threatening. Organisations must anticipate these barriers and develop strategies to address them, including data-driven approaches that document the impact of layered workplace exclusions on productivity, innovation, and retention [

31].

To move toward more inclusive and equitable workplaces that recognise these complexities, we recommend the following actions, presented in order of priority and foundational importance:

Expand inclusion policies to address layered forms of exclusion. Diversity frameworks must be redesigned to explicitly consider various forms of exclusion within multicultural professional environments. This includes developing policy language and implementation tools that recognise the impact of internalised hierarchies and racialised gatekeeping among culturally diverse staff. As Hiruy and Hutton [

29] and Kwansah-Aidoo and Mapedzahama [

32] suggest, this requires moving beyond representation metrics to address the relational quality of workplace interactions across different groups and levels.

Revise accreditation and recruitment frameworks to recognise diverse cultural capital. Accreditation bodies such as the Australian Skills Quality Authority (ASQA) and Australian Qualifications Framework Council (AQFC) should broaden recognition pathways for international qualifications, including partial equivalency models, recognition of prior learning (RPL) assessments tailored for overseas-trained professionals, and streamlined bridging programs co-designed with professional associations. This would disrupt the implicit privileging of Western-acquired credentials and enable more equitable recognition of global professional experience [

7,

34].

Embed intersectionality in organisational practice. Inclusion efforts must be grounded in an intersectional approach that addresses how race, gender, visa status, and class interact to shape workplace experiences across different levels. Leadership training and HR practices should reflect this complexity, as recommended by Colic-Peisker and Tilbury [

25]. This includes developing protocols for addressing complaints of layered forms of exclusion that might otherwise fall outside conventional reporting frameworks.

Adopt and implement language courtesy guidelines. Organisations should introduce formal “language courtesy” policies, such as requiring English (or another agreed shared language) in professional meetings while still valuing linguistic diversity in informal or cultural settings. These guidelines should include: (i) clear expectations for inclusive communication, (ii) training for staff on avoiding exclusionary use of language, and (iii) recognition of multilingualism as an asset in service delivery. Such policies strike a balance between cohesion and cultural expression [

31].

Address emotional labour and psychological safety. The silent burden of emotional regulation must be acknowledged in workplace mental health frameworks. Initiatives to support culturally responsive well-being practices, peer mentorship, and storytelling platforms should be prioritised [

35,

36]. Organisations should develop specific supports for professionals navigating exclusion from multiple sources, including confidential counselling services and resilience-building workshops that validate lived experiences of layered exclusion.

Fund research and dialogue on complex workplace relations. Government agencies such as the Department of Home Affairs, the Australian Human Rights Commission, and state-based Equal Opportunity and Human Rights Commissions should fund research into layered workplace exclusions and their impacts. Priority questions include: How do visa categories and migration pathways affect power dynamics between groups? What organisational structures mitigate layered exclusions? How do generational differences influence intra-community tensions? In addition, platforms for critical dialogue within multicultural communities can foster reflection, healing, and culturally grounded solutions [

31,

37].

It is important for organisations to have clear metrics to assess the effectiveness of these interventions. Success indicators might include reduced turnover rates among African professionals, increased representation in leadership positions, improved scores on psychological safety measures, greater recognition of diverse qualifications, and documented incidents of cross-group collaboration and mentorship. Regular climate surveys that explicitly measure layered exclusion, combined with qualitative methods such as externally facilitated focus groups, can capture subtle changes in workplace dynamics [

38].

Addressing layered workplace exclusions requires coordinated action across multiple stakeholders. Government agencies (e.g., ASQA, AQFC, Department of Home Affairs, Australian Human Rights Commission) must revise accreditation frameworks and provide targeted funding. Employers should commit to evidence-based policy changes and leadership development. Professional associations (e.g., Australian Medical Council, Nursing and Midwifery Board of Australia, Engineers Australia) can design bridging programs and mentoring networks that bridge communities. Community organisations can facilitate dialogue on internal hierarchies, while universities and training institutions can integrate these insights into diversity curricula. As Trenerry et al. [

31] argue, this multi-level approach creates an “ecosystem of inclusion” with reinforcing supports across the professional landscape.

By adopting a more nuanced, relational, and critically reflexive approach to workplace inclusion, policymakers and employers can move beyond symbolic diversity initiatives toward substantive engagement with the complex power dynamics that shape belonging in multicultural workplaces. As Australia positions itself as a globally competitive destination for skilled migrants, addressing layered workplace exclusions will be essential for creating genuinely inclusive professional environments where migrants can contribute their full potential.