Abstract

One of the most important changes after the COVID-19 pandemic was the adoption of remote or hybrid work, which has become increasingly common in many sectors and industries. In this context, based on data from a questionnaire survey, this study aims to explore the perceptions and expectations of students from two Eastern European countries—Romania and Bulgaria—regarding working from home as an effect of the COVID-19 pandemic. To achieve this aim, this study is based on The Job Demands–Resources Theory and the Task–Technology Fit model, which provide an important theoretical framework in interpreting the results. The research employed a non-probability sampling method, with the final sample including 260 respondents from various bachelor’s, master’s, and doctoral programs from two universities, 115 from Romania and 145 from Bulgaria. Data analysis was performed using descriptives statistics, nonparametric correlation analysis, nonparametric tests, as well as multinomial logistic regression and a two-step cluster analysis. The empirical results showed that there are significant differences between the two countries in terms of several aspects related to working from home. We found that the national context influences how people perceive the advantages and disadvantages of working from home and what skills are most important in the post-pandemic labor market. However, respondents have similar expectations regarding future working arrangements, with the majority wanting a hybrid work style. Consequently, the COVID-19 pandemic has had a powerful effect on how people currently work, an effect that will also continue in the future.

1. Introduction

Working from home is not a new phenomenon, but the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic has led to a sudden and significant increase in its popularity in a very short time, which brought a major change in the labor market. One of the most important changes was the adoption of remote or hybrid work, which has become increasingly common in many sectors and industries. This phenomenon has been studied and presented under various names over time (e.g., telework, remote work, home office, working from home), but these usually refer to work being carried out from home or any other location than that provided by the employer [1].

According to Eurostat data, in 2008 less than 8% of employees in EU Member States (aged 15–64) worked from home at least sometimes, while in 2019 this percentage was just over 11%. The pandemic led to a significant increase in this percentage, which exceeded 18% in 2020 and reached nearly 22% in 2021, the largest increase being mainly among people who “usually” worked from home. Regarding young people aged 15–29, Eurostat data show that in EU27, 14.5% worked from home in 2020, while in 2021 the percentage reached 18% [2]. Therefore, it is important to note that during the pandemic, young people were less likely to work from home compared to adults or older people [3].

Although multiple studies have been conducted on this topic since the beginning of the pandemic, there are still gaps in our understanding of how younger generations have been affected by the changes brought by the pandemic in the labor market. They represent an extremely important group, given that they are mainly students or graduates who have entered or are in the process of entering the labor market and who will contribute significantly to the future dynamics of the labor market. However, studies on working from home among young people and their perceptions of this aspect remain limited, especially at the level of EU member states, even though the literature on teleworking has grown considerably in recent years. Moreover, comparative research between member states, especially those in Central and Eastern Europe, is almost non-existent. In this regard, Romania and Bulgaria are among the countries underrepresented in the literature. The lack of this perspective in literature represents a significant gap that can make it difficult to anticipate how young people will relate to the labor market, where working from home and flexibility are becoming increasingly widespread.

In this context, it is important to investigate how young people perceive working from home in the post-pandemic period. The aim of this study is to explore the perceptions and expectations of students from two Eastern European countries—Romania and Bulgaria—regarding working from home as an effect of the COVID-19 pandemic. To achieve this aim, this research pursues the following objectives:

- Analyze students’ perceptions of the effectiveness, advantages, and disadvantages of working from home, as well as its impact on stress levels, work–life balance, and other professional factors;

- Identify students’ expectations regarding the most important skills in the post-pandemic labor market and the characteristics of the future job;

- Highlight the implications for universities and the labor market.

Given the purpose and objectives of the research, this study makes a relevant contribution to literature because it highlights students’ perspectives on this topic, a group that is often neglected in this type of research, but which is extremely important in the post-pandemic labor market. Another relevant and original aspect of the research is the comparative approach between the two countries, Romania and Bulgaria, which offers a regional perspective on a topic that is of global interest.

The analysis is based on data collected via questionnaire from undergraduates, master’s students, and doctoral students at two prestigious universities from Romania and Bulgaria. Therefore, this study aims to test the following hypotheses:

H1:

There is a statistically significant difference between Romanian and Bulgarian students’ perception of the effectiveness of working from home.

H2:

There is a statistically significant difference in the perceived importance of saving commuting time compared to other advantages of working from home among respondents in both countries.

H3:

There is a statistically significant difference in the perceived importance of Social isolation compared to other disadvantages of working from home among respondents in both countries.

H4:

There are statistically significant differences between the two countries in terms of perceptions of the advantages and disadvantages of working from home.

H5:

There is a statistically significant difference in the perceived importance of Digital skills compared to other skills in the post-pandemic labor market among students in both countries.

H6:

There is a statistically significant difference in students’ preferences for hybrid, home-only and office-only working models in both countries.

To better interpret students’ perceptions and expectations regarding working from home, we will draw on two theoretical perspectives relevant to this study: the Job Demands–Resources (JD–R) theory and the Task–Technology Fit (TTF) model. The JD-R theory [4,5], which was developed at the beginning of this century, represents a widely used theoretical framework, especially in occupational psychology, which starts from the premise that each job has its own specific demands and resources. Demands involve various physical, psychological, social, and organizational aspects that require effort or certain skills and are associated with certain costs, while resources refer to the same aspects but help achieve goals, reduce the costs associated with requirements, and stimulate personal and professional growth and development [4,5,6]. Recently, this theory has also been applied in studies on the effects of the pandemic and working from home. These studies have shown that resources such as technological skills and organizational support mitigate demands such as stress, social isolation, and heavy workloads [7], but also that intensive use of technology in working from home can generate costs to well-being, highlighting the important role of resources in maintaining balance [8].

The second theoretical perspective relevant to this study is represented by the Task–Technology Fit (TTF) model. This model shows that employee satisfaction and performance depend on the extent to which available technology helps them perform their tasks [9,10]. Thus, we can say that the efficiency of working from home depends on the connection between tasks and available digital technologies. A recent study addressing this theory showed that tasks adapted to digital technologies improve performance but also reduce feelings of loneliness when working from home [11].

These two theoretical models complement each other providing an appropriate framework for interpreting the results of this study. The first theory highlights the importance of balance between demands and resources in the workplace, while the second emphasizes the importance of matching digital technologies to specific tasks.

This paper is structured as follows: Section 1 contains the introduction, which presents some important ideas about the topic of the paper, the context, as well as the objective and research hypotheses. Section 2 provides a literature review of the most relevant studies related to young people and working from home because of the COVID-19 pandemic. Section 3 describes the data and methods employed in this study. Section 4 presents empirical results, which are organized into three subsections. The profile of student respondents from the two countries is presented in Section 4.1. Section 4.2 explores students’ perceptions of working from home, while Section 4.3 analyzes students’ expectations regarding the future of work. Section 5 is for discussion, while Section 6 presents the main conclusions.

2. Literature Review

Working from home is not something new; it has existed for centuries, but nowadays it has become increasingly important and accessible to more people. According to ILO, before the COVID-19 pandemic, there were 260 million people working from home globally, representing 7.9% of the employed workforce [12]. However, according to a European Commission study, working from home was mainly practiced occasionally by highly qualified professionals and managers in EU member states before the pandemic [13]. Likewise, the proportion of people working from home varied greatly from country to country, with countries such as Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Bulgaria, and Romania having almost no home-based workers, while more than one in four employees worked from home at least occasionally in countries such as Finland, Sweden, Denmark, and the Netherlands [3]. In this regard, Andrei [14] traces the evolution of remote work in the European Union and Romania, noting that despite favorable technological conditions, telework remained limited in Romania until the pandemic accelerated its adoption.

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a significant impact on the labor market, with working from home becoming a necessity for many individuals, but also a way of adapting to this major shock [15]. However, even though the pace of working from home accelerated after the pandemic outbreak, differences remained depending on individuals’ professional and occupational status, the nature of their activity, and their country’s level of development [16]. The differences in the share of individuals working from home across countries can be explained by several factors, including the industrial and occupational structure of the economy, the level of individuals’ digital skills, the degree of internet connectivity, and access to appropriate technical equipment [15]. Other studies have shown that working from home was associated with high-level occupations (managers and professionals, while technicians and other groups were less likely to work from home), higher levels of education (over 30% of individuals with higher education worked from home at least sometimes, compared to only 10% of those with secondary education and only 4% of those with primary education), fewer employees in the company, and a high level of digital skills [3,17,18,19].

Romania and Bulgaria are among the EU member states where the share of people who worked from home before the pandemic was very low. According to Eurostat data, in 2019 just around 1% of the employed workforce (15–64 years old) in these countries worked from home at least part of the time [2]. In Romania’s case, this may also be due to the fact that remote working was officially regulated in 2018, shortly before the outbreak of the pandemic [20]. During the pandemic, the two countries recorded among the lowest percentage increases in the share of individuals working from home, even though the in-crease was more than five times higher than the pre-pandemic level, reaching approximately 6% in Bulgaria and 7% in Romania in 2021 [3].

According to Bălăcescu et al., the quality of digital skills is one of the important fac-tors in quickly adapting to working from home. Therefore, this may be one of the reasons why the prevalence of working from home in Romania and Bulgaria is quite low compared to other Member States, given that the 2020 DESI index ranks them in the bottom four places alongside Greece and Italy [16]. Even though both countries were dealing with low digitization and less use of technology [21], the pandemic accelerated the adoption of digital technologies, remote work and digital services leading to a significant increase in internet use, especially in Romania [22]. On the other hand, a study from Neagu et al. shows that there are significant differences among young people in terms of digital skills depending on their place of residence, with those in rural areas having an extremely low level compared to the EU average and those in urban areas [23].

The existing body of research on the sudden shift to remote work during the COVID-19 pandemic reveals both significant advantages and notable difficulties (Table 1). One of the most evident benefits was the reduction in commuting time, which not only decreased stress but also freed up hours that could be dedicated to family, personal activities, or professional development [15,24,25,26]. Flexible schedules give employees more control over their work and make it easier to combine job tasks with family responsibilities [15,26,27,28,29]. Remote work has also been linked to a better work–life balance, as employees can more easily manage professional and personal duties [15,26,30,31]. In knowledge-based jobs, remote work has sometimes led to higher productivity, since tasks can be completed more efficiently from home [22,27,30]. Working from home often reduces expenses for transport, meals, and clothing [24,32]. Remote work can support the development of digital competences, which is especially important for young people entering the labor market [7,31,33]. Hybrid models are increasingly seen as a sustainable option, combining the flexibility of remote work with the social benefits of office presence [3,29,34,35,36]. It has been found that hybrid work is associated with lower levels of mental distress compared to fully remote or fully on-site arrangements [36]. The shift to hybrid models documented by Iogansen et al. [34] appears to be one of the pandemic’s most lasting workplace transformations. Hybrid work has recently been defined more precisely as the combination of on-site and remote practices that differ by communication mode, location, and timing, providing greater conceptual clarity for assessing its outcomes [37].

Turning to the disadvantages, the most common issue raised is social isolation. Many employees miss informal conversations and teamwork, which are harder to reproduce online [11,25,38]. Connected to this is the problem of unclear boundaries between work and private life [15,26,35,39,40,41,42]. When the home becomes the office, switching off at the end of the day can be difficult, which may lead to stress or even burnout. Recent ILO analysis further warns that the expansion of remote and hybrid work has increased the collection and use of workers’ digital data, raising concerns about privacy and surveillance in the home-based workplace [42]. Another theme is videoconference fatigue, reported especially in the first years of the pandemic [18]. In some countries, employees also face technical barriers and poor access to digital tools, which limit the effectiveness of remote work [23,43]. A further concern is gender inequality. Women working from home are more likely to experience emotional exhaustion, higher stress, and greater conflicts between work and family life compared to men [17,38,44,45,46]. Remote work often creates communication and coordination issues, as employees report weaker collaboration, less informal knowledge sharing, and difficulties in project management [3,25,26,28,47,48]. Some studies also mention reduced career visibility and promotion opportunities [26,49], as well as a heavy dependence on organizational support to make remote and hybrid arrangements work in practice [28,29,41,47]. Mandatory remote work has been linked to increased psychological stress, including emotional exhaustion, videoconference fatigue, and difficulties in balancing professional and personal life [25,35,38,39,44].

Table 1.

Advantages and disadvantages of remote work.

Table 1.

Advantages and disadvantages of remote work.

| Advantages | Supporting Studies | Disadvantages | Supporting Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Saving commuting time | Ipsen et al. [25]; Kozioł-Nadolna [24]; Oo et al. [26]; Vasilescu et al. [15] | Social isolation | Abelsen et al. [11]; Ipsen et al. [25]; Emmerich et al. [38] |

| Flexible schedules and autonomy | Alipour et al. [27]; Biron et al. [28]; Dara et al. [29]; Oo et al. [26]; Vasilescu et al. [15] | Blurred work–life boundaries | Abraha [42]; Athanasiadou & Theriou [40]; Bennett et al. [39]; Ferreira & Gomes [41]; Oo et al. [26]; Tobia et al. [35]; Vasilescu et al. [15] |

| Improved work–life balance | Cai et al. [31]; Ishii et al. [30]; Oo et al. [26]; Vasilescu et al. [15] | Videoconference fatigue | Bennett et al. [39] |

| Higher productivity | Alipour et al. [27]; Dumitra & Aldea [22]; Ishii et al. [30] | Technical barriers | Neagu et al. [23]; Sostero et al. [43] |

| Reduced expenses | Kozioł-Nadolna [24]; Radziukiewicz [32] | Gender disparities | Bhumika [44]; Couch et al. [45]; Emmerich et al. [38]; Kley & Reimer [17]; van der Lippe & Lippényi [46] |

| Development of digital competences | Cai et al. [31]; Ferhataj et al. [33]; Karaca et al. [7] | Communication and coordination issues | Biron et al. [28]; Carillo et al. [47]; Eurofound [3]; Ipsen et al. [25]; Mthombeni & Matli [48]; Oo et al. [26] |

| Hybrid models as sustainable option | Dara et al. [29]; Eurofound [3]; Iogansen et al. [34]; Tobia et al. [35]; Treviño Garcia & Christensen [36] | Psychological stress (mandatory remote work) | Bennett et al. [39]; Bhumika [44]; Ipsen et al. [25]; Emmerich et al. [38]; Tobia et al. [35] |

| Career visibility/promotion | Oo et al. [26]; Țălnar-Naghi [49] | ||

| Dependence on organizational support | Carillo et al. [47]; Biron et al. [28]; Dara et al. [29] Ferreira & Gomes [41] |

Organizational and policy responses varied significantly. France saw successful adaptation when companies provided proper support [47], while Poland developed specific regulatory frameworks [32]. Evidence from Indonesia indicates that hybrid work can foster employee well-being, but only when accompanied by strong organizational support, while lack of such support increases the risk of burnout [29]. Key studies demonstrate that remote work’s effectiveness depends on proper task–technology alignment [11], organizational support structures [28,47], individual digital competencies [7,16], and supportive policy frameworks [13,32]. Mthombeni and Matli’s systematic data analysis [48] identified three critical barriers to sustainable remote work implementation: inadequate home office infrastructure, insufficient managerial training, and unequal access to digital tools across socioeconomic groups.

A systematic review of telework studies stressed both its benefits, such as flexibility and reduced costs, and its drawbacks, including isolation and coordination problems, while also pointing to the lack of clear definitions and theoretical frameworks [40]. More recent reviews using data-driven approaches also emphasize recurring challenges in productivity, coordination, and employee well-being [48]. An AI-based topic modeling analysis further shows that studies repeatedly focus on productivity, work–life balance, mental health, and digital transformation, but still leave many issues unresolved [50]. While much of the existing research has addressed remote and hybrid work in general, it is equally important to examine how these transformations affect specific groups, particularly younger generations. Young people, including those still in education and those entering the labor market at the beginning of their careers, are an extremely important group, but also an extremely vulnerable one to changes, especially during times of major shocks, such as the crisis caused by the pandemic. They represent an important group because they should be both the engine of economic development and an energizing factor for a society’s economy, as well as a source of support for the generations who once worked for them [51]. A study conducted on young people in Romania and Hungary found that, while young people in Hungary prefer a partially flexible work schedule, young people in Romania prefer a completely flexible work schedule [52]. Another study showed that job satisfaction among young people who worked from home before the pandemic was much higher than among older people, but this difference changed during the pandemic when job satisfaction inincreased with age, even for people over 40 [49]. A recent survey of undergraduate students in the United States found that, while many appreciated the flexibility of remote work, they also worried about its potential negative impact on career opportunities [53].

Even though young people are extremely important for every society, to our knowledge there is a significant lack of studies at the level of EU member states, but especially in Romania and Bulgaria, on the consequences of the pandemic crisis on young people, their perceptions of the changes it has brought about in the labor market, and how they view working from home in this context. Therefore, this study aims to shed some light on this topic by analyzing the perceptions of undergraduate, master’s, and doctoral students from two major universities in Romania and Bulgaria regarding working from home because of the pandemic, as well as their future expectations in terms of ways of working.

3. Materials and Methods

This study aims to explore the perceptions and expectations of students from two Eastern European countries—Romania and Bulgaria—regarding working from home as an effect of the COVID-19 pandemic. To achieve this objective, we conducted primary research based on a questionnaire survey. The research employed a non-probability sampling method consisting of a convenience sample of students from two universities who voluntarily agreed to participate and completed the questionnaire. This represents a limitation of the study, as the results reflect the perceptions of the students participating in this study, without being able to generalize to the entire student population. Nevertheless, the results provide valuable insights into how students perceive working from home and what their expectations are regarding the labor market, which is an important starting point for future research with larger and more representative samples.

The online questionnaire in Google Forms was distributed to undergraduate, master’s, and doctoral students at two economics universities—Bucharest University of Economic Studies in Romania and University of Economics–Varna in Bulgaria via student platforms, email, or social media. The data was collected between 17 June and 7 July 2025, and it took about 10 min to fill out the questionnaire.

Prior to participation, all participants were clearly informed about the purpose of the research, the fact that their participation was entirely voluntary and the responses submitted are fully anonymous and used only for statistical and research purposes. Data was gathered without including any personally identifiable details that could disclose the students’ identities, and no IP addresses or other digital traces were stored.

The final sample included 260 respondents from various bachelor’s, master’s, and doctoral programs at the two universities, 115 from Romania and 145 from Bulgaria. The sample size was determined by the availability and willingness of students to respond to this questionnaire during the data collection period.

The structured questionnaire used in this research was designed to investigate students’ perceptions and future expectations regarding working from home in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. It included 23 questions grouped into three sections. The first section, which contains 13 questions, consists of socio-demographic data such as gender, age, place of residence, level and field of education, current occupation and field of activity, as well as the number of days currently worked from the office or from home. The second section includes 5 questions about perceptions of working from home, while the third section includes 5 questions about respondents’ future expectations regarding how work will be carried out. The second section examined students’ perceptions of the efficiency of working from home compared to working in the office, as well as the main advantages and disadvantages of working from home (where students had to choose a maximum of 3 advantages and 3 disadvantages). Among the mentioned advantages are “flexible schedule”, “higher productivity”, and “saving commuting time”, while among the disadvantages are the following: “technical issues”, “social isolation” and “communication difficulties with colleagues”. This section also used a 5-point Likert scale to measure respondents’ degree of agreement or disagreement (from Strongly disagree to Strongly agree) on some items that addressed the impact on stress, work–life balance, team communication and professional development. Among these items are the following: “Working from home reduces daily stress”, “Working from home offers more balance between personal and professional life”. The third section began with a question about the most important skills in the post-pandemic labor market (where students had to choose a maximum of 3 skills), while the next question was related to the type of work they would like to do in the future. They were also asked which is the most suitable work model for their generation and if they will be willing to refuse a job that does not offer flexibility. Furthermore, students’ expectations regarding the importance of some characteristics of their future workplace (the possibility of working remotely, flexibility in schedule, security/stable contract, learning and development opportunities, work–life balance support) were measured using a five-point Likert scale (from Not at all important to Very important). The entire questionnaire used for data collection is included in Appendix A, at the end of the manuscript, in order to provide transparency and replicability.

The questions included in the second and third sections of the online questionnaire were developed and formulated by the authors specifically for this study, taking into account the research nature of the study. It should be emphasized that no directly adopted or adapted validated scales were applied in the preparation of the questions. However, their formulation followed established research practices from reputable scientific publications that focus on the thematic area related to remote and hybrid work and the future expectations of students on the labor market after the pandemic situation [17,28,37]. The application of this approach allowed, on the one hand, the authors to reflect the specific context and characteristics of students in the two Eastern European countries when compiling the questionnaire, and on the other hand, the questions to be conceptually consistent with established research scientific publications.

Data were collected using two Google Forms questionnaires, one in Romanian and one in Bulgarian. The resulting two databases were translated into English and combined into a single dataset. This dataset allowed for comparative and aggregate analysis using IBM SPSS Statistics Premium Faculty Pack Version 30.

To analyze students’ perceptions of working from home, descriptive analyses and graphs were performed. In addition, a nonparametric correlation analysis was carried out, as well as the nonparametric Kruskal–Wallis’s test to see if there are significant differences in certain statements regarding working from home between different groups, based on socio-demographic variables. Several chi-square tests were also performed to see if there are significant differences between the two countries in terms of various aspects related to working from home because of the pandemic. Given that all items related to advantages, disadvantages and the most important skills are coded as binary variables (1 = mentioned, 0 = not mentioned), we conducted some non-parametric procedures. We used Cochran’s Q test to assess the differences in the frequency of responses across items, while the Kendall’s W coefficient measured the degree of agreement among respondents related to the perceived advantages, disadvantages and the most important skills. We also conducted post hoc McNemar pairwise dominance tests to see if there are significant differences between items. This study also includes a multinomial logistic regression analysis and a two-step cluster analysis.

Multinomial logistic regression was employed to examine factors influencing young people’s preferences for future work arrangements (office-only, hybrid, or home-only). Given the nominal nature of the outcome variable, the method was considered appropriate. It was applied to model how categorical and continuous predictors affect the likelihood of belonging to one category relative to a reference group (office-only). The predictors included demographic characteristics (age, gender, country), perceptions of working from home (efficiency, stress reduction, work–life balance), and job flexibility preferences (importance of remote work, schedule flexibility). Categorical variables such as gender and country were specified as nominal, while ordinal variables were tested for linearity assumptions. The analysis was conducted in SPSS using the NOMREG procedure. In this process, dummy variables were created automatically and reference groups were specified. To ensure robustness, categories with fewer than 5% of cases were merged or excluded. Multicollinearity was checked through variance inflation factors, and proportional odds assumptions were verified for ordinal variables. A forward stepwise selection procedure was applied to identify the most relevant predictors. The process was initiated with an empty model, and variables were added sequentially according to the significance of likelihood-ratio statistics (entry criterion: p < 0.05). Non-significant predictors (p > 0.10) were removed to maintain parsimony. The final model retained only variables that improved prediction accuracy, as determined by the Bayesian Information Criterion. Model fit was assessed through likelihood-ratio tests for predictor significance and Nagelkerke’s pseudo-R2 for explained variance. This approach was adopted to achieve a balance between model fit and complexity while minimizing the risk of overfitting.

A two-step cluster analysis was used to identify respondent segments based on work flexibility preferences. The algorithm was chosen for its ability to handle mixed variable types and to treat ordinal measures as categorical data. The analysis included both nominal categorical variables—future work preference (office-only, hybrid, home-only) and willingness to refuse inflexible jobs—and ordinal variables, such as the perceived importance of remote work and schedule flexibility, which were treated as categorical. The clustering procedure applied a likelihood-based distance measure, using multinomial distributions for categorical variables while applying appropriate metrics for each variable type. This approach preserved the ordered nature of ordinal variables without assuming equal intervals. The Bayesian Information Criterion was used to automatically determine the optimal number of clusters. Three clusters were identified and labeled according to their dominant characteristics: Office-Centric Traditionalists, Flexibility-Seeking Hybrid Workers, and Remote-First Advocates. The stability of the solution was assessed with discriminant analysis, which confirmed the distinctiveness of the segments.

4. Results

4.1. Respondent Sample Profile

This section presents the socio-demographic profile of the respondents. 115 responses were collected from Romania and 145 from Bulgaria. Of the total 260 respondents, 69.6% are female, 68.5% come from large cities and 19.2% from small- or medium-sized cities. In terms of age, they range from 18 to 55, with 74.6% of respondents aged between 18 and 29. Most respondents are enrolled in bachelor’s degree programs (61.9%), followed by doctoral programs (27.3%) and master’s programs (8.8%). Of all respondents, 74.2% are enrolled in full-time programs and 11.5% in distance learning programs. More than half of the respondents are studying economics, followed by those studying computer science and information technology (29.2%) and those studying administration and management (10.4%). Also, currently 49.2% work full-time, 13.8% work part-time, and 21.5% are not working. The fields in which most respondents currently work are: IT and software development (15.8%), Sales, retail, and customer service (11.9%), Finance, banking, or insurance (10.4%), Tourism, hospitality, or event planning (7.7%), and Education and professional training (7.3%). Furthermore, 34.6% work in large companies with over 250 employees, 14.2% in small companies (10–49 employees), while 11.9% of respondents work in micro-enterprises and 11.9% in medium-sized companies.

Regarding studies during the pandemic, 53.1% of respondents became students after the pandemic, while 31.5% were students for part of that period, and 15% were students throughout the pandemic period. Also, 46.2% did not work during the pandemic, 24.2% worked from their workplace, 18.5% worked both from home and from their workplace, while 11.2% worked only from home during the pandemic. Currently, among respondents who have a job, 51.5% work only from their workplace, while 15.2% work only from home (remotely). In addition, 11.3% work two days from home and the rest at their workplace, while 9.8% of the respondents work three days from home and the rest at their workplace.

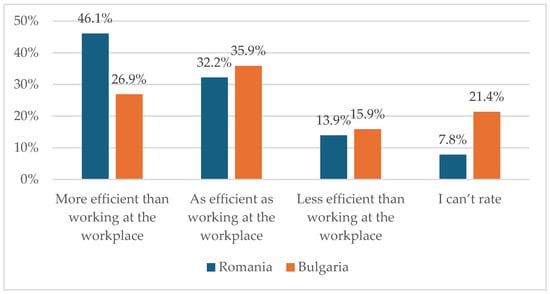

4.2. Students’s Perceptions Regarding Working from Home

In order to study students’ perceptions of working from home, respondents were asked to compare its effectiveness with that at the workplace. Figure 1 shows that working from home is perceived as more efficient than working at the workplace, especially by respondents in Romania (46.1% vs. 26.9%), while respondents in Bulgaria are more uncertain, with 21.4% unable to rate the efficiency of working from home compared to only 7.8% of respondents in Romania. On the other hand, the proportion of students who considered working from home to be as effective or less effective than working at the workplace is relatively similar in both countries. The chi-square test performed on these data showed that there are significant differences between the two countries. The test results () show that perceptions of the effectiveness of working from home are influenced by the national context.

Figure 1.

In your opinion, working from home is: Romania vs. Bulgaria.

Another question in this section of the questionnaire asked them to express their level of agreement for some statements related to working from home using a five-point Likert scale, ranging from “Strongly disagree” to “Strongly agree”. Table 2 shows the distribution of responses. Over 73% of respondents agree that working from home reduces daily stress, while three out of four respondents believe that it offers more balance between personal and professional life. Furthermore, only one-third of respondents believe that working from home negatively affects team communication, and only 23% of them agree that it reduces their chances of promotion/professional development. Furthermore, 78% want their future job to allow them to work from home.

Table 2.

Distribution of responses regarding statements related to working from home (%).

In order to better examine respondents’ perceptions and how these dimensions of working from home are associated with each other, a nonparametric correlation analysis was performed between the five items described above, using Kendall’s tau_b coefficient. The results can be seen in Table 3. One of the positive and statistically significant correlations is between the first two statements, which shows us that respondents who experience less stress due to working from home are more likely to report a better work–life balance. Furthermore, these two statements are positively and significantly correlated with the last statement in the table, the one related to the desire to work from home, from which we can conclude that the two benefits, stress reduction and work–life balance, determine individuals’ desire to work from home in the future.

Table 3.

Kendall’s tau_b nonparametric correlation matrix for statements related to working from home.

On the other hand, the analysis also reveals significant negative correlations. One of these is between work–life balance and reduced chances of promotion, which shows us that those who value this balance are less concerned about the impact of working from home on their career. Moreover, the statements regarding reduced chances of promotion and negative impact on team communication are negatively correlated with the statement regarding desire to work from home. This shows that those who perceive working from home as affecting team communication and professional development are less eager to do so in the future.

Furthermore, based on the same statements presented above, we want to see if the perception of working from home is influenced by various socio-demographic variables. In this regard, the Mann–Whitney and Kruskal–Wallis tests were used to see if there are significant differences between groups in terms of perceptions related to working from home. All socio-demographic variables available in the database were tested, but Table 4 shows only those that show statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) for at least one of the five statements.

Table 4.

Differences in Student’s perceptions regarding the following statements of working from home based on socio-demographic variables.

In the case of the statement “Working from home reduces daily stress” there are significant differences in respondents’ perceptions depending on their level of study but not depending on the other variables considered in the analysis. Regarding the second statement, “Working from home offers more balance between personal and professional life” it can be observed that there are significant differences in students’ perceptions depending on where they carry out their activities and how many days they work from home in the present. For the third statement, “Working from home negatively affects team communication” the type of study program is responsible for the differences in students’ perceptions, this variable leading to significant differences also in the case of statement four, “Working from home reduces chances of promotion/professional development”, along with another variable related to the place where they carry out their activities. Furthermore, in the case of the last statement, “I would like my future job to allow working from home” we can see that there are significant differences in students’ perceptions depending on their type of study program, their field of study, their field of work, but also depending if they worked during the pandemic and depending on where they carry out their activities and how many days they work from home in the present.

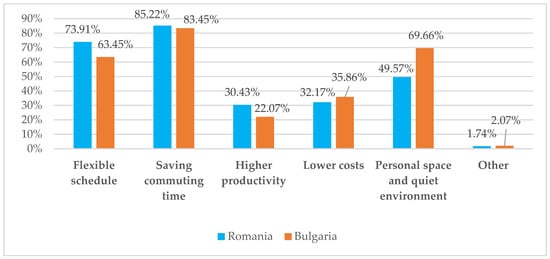

When analyzing students’ perceptions of working from home, it is important to consider also the advantages and disadvantages they attribute to this type of work. The questionnaire included two questions related to the main advantages and disadvantages of working from home for respondents, where each respondent could choose a maximum of three advantages and a maximum of three disadvantages.

Figure 2 shows that the most important advantages considered by respondents are: Saving commuting time, Flexible schedule, Personal space and quiet environment. Regarding the first advantage mentioned above, we can see that the proportion of respondents who chose it is similar in the two countries analyzed. However, significant differences can be observed in the case of the other two advantages: a higher proportion of respondents in Romania consider flexible schedule to be a main advantage of working from home, while those in Bulgaria favor personal space and quiet environment much more, which could indicate that they value comfort in the workplace more highly. It should also be noted that respondents in Romania consider high productivity to be a greater advantage of working from home than those in Bulgaria, while in terms of lower costs, the proportion of respondents who consider this to be an important advantage is similar in both countries. To determine if there are statistically significant differences in perceptions of the advantages of working from home between the two countries, a chi-square test was performed. The test results () showed that there is a significant association between the country and the chosen advantages. Among the other socio-demographic variables that were tested using the same test, only the place of residence, occupational status, and the number of days worked from home per week showed statistically significant associations with the chosen advantages.

Figure 2.

The main advantages of working from home—Romania vs. Bulgaria.

Furthermore, the analysis based on Cochran’s Q test showed that there are statistically significant differences in the frequency with which the advantages of working from home were selected by students (Q = 422.615, p < 0.001). The Kendall’s W coefficient of concordance (W = 0.33) shows a moderate level of agreement among students, which indicates that although they agreed to a greater extent with the main advantages of working from home (saving commuting time, flexible schedule), there were some differences in the importance given to the other advantages. Post hoc McNemar pairwise dominance tests were also conducted to see which of the advantages were perceived as the most important. The results of these tests confirmed that saving commuting time was the advantage selected significantly more frequently (p < 0.001), with a medium to large effect size (Cohen’s g > 0.40). Additionally, it was found that advantages such as flexible schedule, personal space and quiet environment were significantly different from advantages such as lower costs and higher productivity.

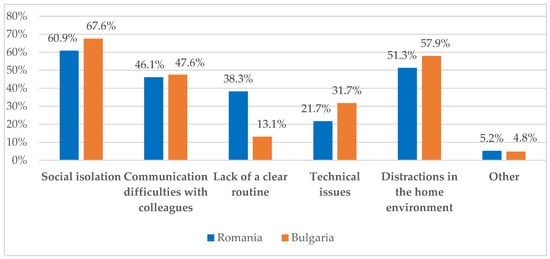

Figure 3 shows that the most important disadvantages considered by respondents are: Social isolation, Distractions in the home environment, and Communication difficulties with colleagues. Regarding the last disadvantage mentioned above, we can see that the proportion of respondents who chose it is similar in the two countries. On the other hand, regarding the other two disadvantages already mentioned, there is a significant difference between the proportion of respondents in the two countries, with more respondents in Bulgaria perceiving them as significant disadvantages than those in Romania. Furthermore, respondents in Romania consider that there is a lack of a clear routine when working from home, while those in Bulgaria seem to encounter more technical issues when working from home compared to those in Romania. In this case a chi-square test was also performed to see if there are statistically significant differences in perceptions of the disadvantages of working from home between the two countries. The test results () showed that there is a significant association between the country and the chosen disadvantages. Moreover, other socio-demographic variables that showed statistically significant associations with the chosen disadvantages after performing the same test were the place of residence, the type of the study program, the way of working during the pandemic and the number of days worked from home per week.

Figure 3.

The main disadvantages of working from home—Romania vs. Bulgaria.

As in the case of advantages, the analysis based on Cochran’s Q test showed that there are statistically significant differences in the frequency with which the disadvantages of working from home were selected by students (Q = 250.792, p < 0.001). In this case, the Kendall’s W coefficient of concordance (W = 0.19) shows a low to moderate level of agreement among students which may indicate the fact that students have experienced various negative aspects of working from home. Although social isolation was the main disadvantage mentioned by most respondents, communication difficulties with colleagues and distractions in the home environment are also significant disadvantages of working from home for students. These results were also confirmed by the post hoc McNemar pairwise dominance tests, which showed that social isolation was the disadvantage selected significantly more frequently (p < 0.001), with a medium to large effect size (Cohen’s g between 0.40 and 0.60). Statistically significant differences also appeared in the case of disadvantages such as communication difficulties with colleagues and distractions in the home environment compared to disadvantages such as technical issues and lack of a clear routine.

The Chi-Square test results () also revealed significant differences between respondents in the two countries for the following question: “Do you think the COVID-19 pandemic has influenced the way people work today?” In Romania, 95.7% of respondents believe that the pandemic has changed the way people currently work, and only 1.7% do not believe this, while 2.6% of respondents don’t know. In contrast, in Bulgaria, a much higher percentage, 10.3%, answered “I don’t know” to this question, and 7.6% do not believe this, while only 82.1% agree that the pandemic has influenced the way people work today.

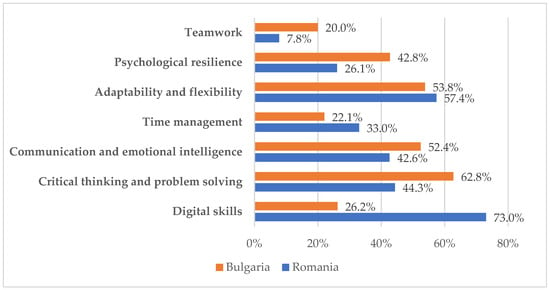

4.3. Students’s Expectations About Future Work

Students’ expectations regarding the future of work are also an important topic to be addressed in this study. A noteworthy aspect related to their current or future work is their skills. Therefore, the first question in this section of the questionnaire is: Which skills do you think are more important in the post-pandemic labour market? (choose maximum 3). Figure 4 shows the most important skills for respondents in Romania and Bulgaria, as well as the differences between the two countries in this regard. A significant percentage of respondents in Romania (73%) consider digital skills to be very important in the post-pandemic labor market, compared to only 26.2% of respondents in Bulgaria. On the other hand, respondents in Bulgaria consider the following skills to be more important: critical thinking and problem solving (62.8% vs. 44.3%), psychological resilience (42.8% vs. 26.1%), communication and emotional intelligence (52.4% vs. 42.6%) and teamwork (20% vs. 7.8%). Moreover, the importance of adaptability and flexibility was rated similarly by respondents in both countries (57.4% in Romania, 53.8% in Bulgaria), while time management seems to be more important among Romanians (33%) than among respondents in Bulgaria (22.1%). To verify whether these observed differences between the two countries are statistically significant, the Pearson Chi-square test was applied. The test results () confirmed the existence of statistically significant differences between the two countries in terms of the skills considered most important in the post-pandemic labor market.

Figure 4.

The most important skills in the post-pandemic labor market—Romania vs. Bulgaria.

In this case the analysis based on Cochran’s Q test was also conducted, showing that there are statistically significant differences in the frequency with which the most important skills for the post-pandemic labor market were selected by students (Q = 133.708, p < 0.001), indicating that the skills were not perceived equally. Digital skills and adaptability and flexibility are among the most frequently mentioned skills. These are followed by critical thinking and problem solving, communication and emotional intelligence, while time management and teamwork were less often mentioned by students. In this case, the Kendall’s W coefficient of concordance (W = 0.09) shows a low level of agreement, which shows us that individuals have different perceptions of the most important skills in the post-pandemic labor market. These results were also confirmed by the post hoc McNemar pairwise dominance tests, which showed that digital skills and adaptability and flexibility were the skills selected significantly more frequently (p < 0.001), with medium effect sizes (Cohen’s g between 0.30 and 0.45). These results suggest that, in the context of working from home, students value digital skills, adaptability, critical thinking and problem-solving more than other skills, such as teamwork and time management.

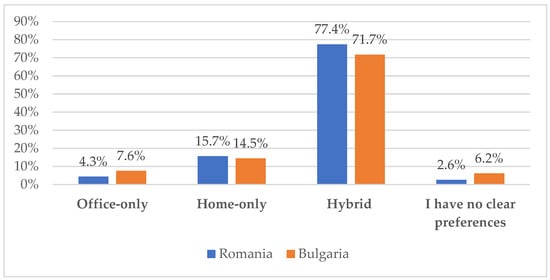

Another relevant aspect in this section is the type of work that respondents want in the future. Figure 5 shows that respondents in both countries prefer a hybrid work style (77.4% in Romania, 71.7% in Bulgaria), followed by those who want to work only from home (15.7% in Romania, 14.5% in Bulgaria), while those who want to work only from the workplace are very few in both countries (4.3% in Romania, 7.6% in Bulgaria). As can be seen, there are no significant differences between the preferences of students from the two countries regarding the type of future work, which was also proven by the Chi-square test. The test results () showed that in this case there are no statistically significant differences between the two countries, so we can say that the country of residence does not influence preferences for the type of future work.

Figure 5.

What type of work would you like in the future?—Romania vs. Bulgaria.

It is also important to see what factors influence these preferences. Therefore, a multinomial logistic regression was performed. The regression analysis includes the dependent variable, which has four categories: office-only (reference category), home-only, hybrid and no clear preferences, as well as a series of predictors initially included in the model. After a forward stepwise selection procedure was implemented, the final model identified only two statistically significant predictors for respondents’ future preferences regarding the type of work. The likelihood ratio test results () show that the final model fits the data better than the null model (without predictors), with the included predictors adding explanatory value. The model also explains approximately 33% of the variability in preference for future job type, which shows moderate explanatory power.

From Table 5 it can be noted that the two statistically significant predictors are: “the possibility of working remotely” and “I would like my future job to allow working from home”. Taking the first predictor into account, the model results show that the probability of preferring to work from home or in a hybrid way increases as respondents’ perception of the importance of remote work increases. Thus, we observe that respondents who prioritize remote work are 9.2 times more likely to prefer working from home in the future than working in an office and 2.4 times more likely to prefer a hybrid work arrangement than the office-only one. Regarding the second predictor, it is noteworthy to mention that individuals who expressed a desire to work from home for a future job are nearly 3.7 times more likely to prefer working from home over working in an office, as well as approximately 1.9 times more likely to prefer a hybrid work model over an office-based one. Therefore, we can see that both predictors increase the likelihood of preferring working from home or hybrid work over office work, with the effect being stronger for working from home, especially in the case of the first predictor. These results show that working from home and hybrid work are future options for today’s students. This creates a need for employers to implement flexible work policies to meet young people’s desires and expectations. Employers should also provide remote internship programs so students can experience working from home in real conditions.

Table 5.

The empirical results of the multinomial logistic regression model.

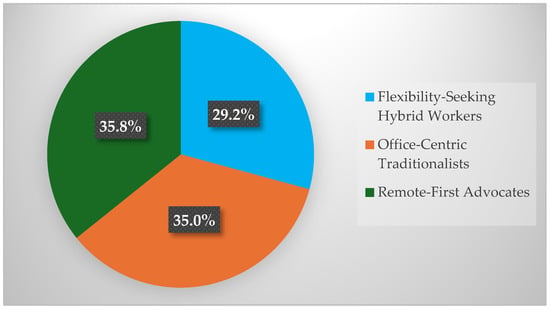

Another important aspect was related to preferences for work flexibility. To identify natural respondent segments, a two-step cluster analysis was conducted. Three distinct clusters were obtained and labeled according to their dominant characteristics. The distribution of respondents across clusters is shown in Figure 6. The first cluster, the smallest group (n = 76), was labeled Flexibility-Seeking Hybrid Workers. This group was characterized by students who desired flexibility but accepted a mix of home- and office-based work. The second cluster, comprising 91 respondents, was labeled Office-Centric Traditionalists. It was defined by a preference for conventional office work. The third and largest cluster (n = 93) was labeled Remote-First Advocates. This group was composed of students who primarily favored working from home combined with greater flexibility. These cluster analysis results also showed students’ preferences for working from home or in a hybrid format. They can assist employers in both countries in better understanding future employees’ expectations and adapting their activities accordingly.

Figure 6.

Distribution of Respondents across clusters.

In the following, we will present some characteristics of each cluster based on the variables considered in the analysis. The first cluster has the highest hybrid-work preference, containing 66% of all respondents who favor this arrangement. In contrast, only 23.1% of all home-only preferring respondents fall into this cluster. The analyses revealed that within the cluster 86.8% would prefer a hybrid working model in the future and 11.8% would prefer working from home and in terms of workplace flexibility, 21.1% of respondents in this group would refuse jobs that do not offer flexibility, while 75% would refuse such jobs only if there are other unfavorable conditions. Furthermore, approximately one-third of them consider remote work to be very important, while the rest consider it important, while flexibility in the work schedule is considered very important by 43.4% and important by the rest of the respondents in this group.

The second cluster contains 87.5% of all respondents who prefer office-only work, but only 7.7% of all respondents who favor home-only work. It demonstrates the highest tolerance for rigid work arrangements, with 72.7% of all respondents unwilling to refuse inflexible jobs. Within this cluster, 15.4% would like to work only from the office in the future, while 74.7% would prefer the hybrid model, and in terms of flexibility, 17.6% would not refuse jobs that do not offer flexibility, while 62.6% would refuse them only depending on other conditions. Furthermore, 62.6% of respondents in this group consider remote work to be moderately important and 12.1% consider it unimportant, while 39.6% consider schedule flexibility to be important and 37.4% consider it only moderately important.

This third cluster includes 69.2% of all respondents who prefer home-only work, representing the highest concentration among all groups. In contrast, it holds just 12.5% of all respondents willing to accept office-only work. Notably, this cluster also accounts for 71.2% of all respondents who would refuse inflexible jobs. Looking ahead, 29% of respondents in this cluster would prefer to work exclusively from home in the future, while 63.4% would prefer a hybrid option. Meanwhile, 90.3% of respondents in this group would categorically refuse a job that does not offer flexibility. Moreover, for this group, the possibility of working from home is important and very important, and flexibility in schedule is very important for all of them.

To validate the three clusters identified above, we performed a discriminant analysis using the same variables as in the cluster analysis. The analysis yielded two significant canonical discriminant functions, the first of which explained 90.6% of the variance (canonical correlation = 0.874), while the second function explained 9.4% of the variance (canonical correlation = 0.500). Furthermore, the Wilks’ Lambda test showed that the functions are statistically significant, confirming that the three clusters are distinct. The structural matrix showed that the strongest correlations with the first discriminant function were related to the variables flexibility in schedule and the possibility of working remotely, while for the second function, the strongest correlation was with the variable represented by the willingness to refuse a job that does not offer flexibility. Furthermore, the classification results indicate a high degree of accuracy, given that 86.3% of the selected cases and 89.7% of the non-selected cases were classified correctly. Therefore, given all these results, the three clusters are strongly validated by the discriminant analysis.

5. Discussion

Working from home is a very important topic at present, given that it can be considered an effect of the COVID-19 pandemic. The discussion below is structured based on the research hypotheses presented at the beginning of this study. The interpretations are based on the statistical results obtained in this study through descriptive statistics and tests such as Cochran’s Q, McNemar, and Chi-square tests. The results are also interpreted in relation to the theoretical framework and compared with previous literature.

One finding of this study showed that, compared to those in Bulgaria, who are more undecided about the efficiency of working from home, respondents in Romania perceive working from home to be more efficient than working in the office. Therefore, there are significant differences between the two countries in terms of perceptions of the effectiveness of working from home, as demonstrated also by the results of the chi-square test. Thus, the national context is one of the important factors that shape students’ perceptions of the effectiveness of working from home. This result confirms H1, given that there is a statistically significant difference between Romanian and Bulgarian students’ perception of the effectiveness of working from home, and aligns with previous evidence showing that attitudes toward telework are influenced by infrastructural support and digital readiness [16], resonating also with Gottlieb et al. [19], who indicated that contextual differences play an important role in shaping attitudes. Another study conducted on researchers showed that of those who worked from home during the pandemic, only 23% considered working from home to be more efficient, 30% reported no difference, while 47% considered that work efficiency had decreased compared to the period before the pandemic [1]. Furthermore, according to the Task–Technology Fit model, how individuals perceive the effectiveness of working from home may depend on how suitable they find the available technologies for their work tasks. In Romania, remote work is associated with greater efficiency because technology is integrated into learning and work practices. In Bulgaria, however, where more technical problems have been reported, the assessment of efficiency has been more cautious. This demonstrates that Bulgarians perceive digital technologies and tasks as having lower compatibility.

Regarding the advantages and disadvantages of working from home, this study found that respondents in both countries perceived saving commuting time as the most important advantage, while social isolation was perceived as the most important disadvantage. These findings confirm the Hypothesis H2 stating that there is a statistically significant difference in the perceived importance of saving commuting time compared to other advantages of working from home among respondents in both countries, and the Hypothesis H3 stating that there is a statistically significant difference in the perceived importance of social isolation compared to other disadvantages of working from home among respondents in both countries. However, there were significant differences between the perceptions of students from the two countries regarding other advantages and disadvantages, as demonstrated by the results of the chi-square tests, which showed that the national context is one of the factors influencing perceptions of the advantages and disadvantages of working from home, alongside other factors such as: the place of residence and the number of days worked from home per week. Therefore, the Hypothesis H4 is confirmed by this results, given that there are statistically significant differences between the two countries in terms of perceptions of the advantages and disadvantages of working from home. Saving commuting time was also found as one of the most important advantages in a study that explored the advantages and disadvantages of working from home in Europe, along with increased flexibility, while the most important disadvantages were: missing colleagues and poor physical working conditions at home [25]. In this context, the Job Demands–Resources theory explains that, depending on the national context, students rely on certain resources which they consider relevant for managing the demands of working from home. Thus, social isolation as a disadvantage reflects a demand that can reduce well-being and increase stress levels, while work–life balance, commuting time savings, and flexible schedules are resources that can increase motivation and engagement.

When considering working from home, skills are also an important factor. Digital skills have become increasingly important since the beginning of the pandemic, with approximately three out of four respondents in Romania considering them among the most important skills in the post-pandemic labor market. However, Bulgarian respondents do not share this opinion, with just over one in four considering digital skills to be among the most important, while most consider critical thinking and problem solving as one of the most important post-pandemic skills. Thereby, the Hypothesis H5, stating that there is a statistically significant differnece in the perceived importance of digital skillls compared to the other skills in the post-pandemic labor market among students in both countries, is not supported by these results. These differences between the two countries may be due to educational or cultural characteristics, or to differences in the structure of the labor market. The importance that Romanian students place on digital skills confirms previous research identifying technological competence as a key resource for adapting to working from home [7]. Meanwhile, the importance that Bulgarian students place on soft skills reflects the conclusions of other studies highlighting the psychosocial dimension of working from home [24,30]. However, these results differ from those of other study that emphasize the universal importance of digital skills across EU member states [18]. In this case, JD-R theory can help explain the differences that have emerged. Thus, resources can take various forms, and in a context where digital skills are less valued as important, as is the case with students in Bulgaria, other resources such as critical thinking, problem solving, and communication are perceived as more relevant in the context of working from home. Furthermore, these results highlight the importance of preparing students with various types of skills (digital skills, adaptability, communication, problem solving), not just technical ones, suggesting that universities should adapt their study programs to the national context and the need for certain types of skills.

Although working from home was initially a short-term solution at the beginning of the pandemic in an attempt to limit the spread of the virus, forcing millions of employees to adopt new ways of working, it now appears that this trend will continue [54]. When asked what type of work they would prefer in the future, over 70% of respondents in each of the two countries analyzed in this study chose the hybrid model. This result is consistent with the Hypothesis H6, stating that there is a statistically significant difference in students’ preferences for hybrid, home-only and office-only working models in both countries, and with other studies which have shown that the hybrid working model is the most sustainable organizational change that has taken place since the pandemic [3,34]. Furthermore, other studies have shown that this hybrid way of working will not disappear completely in the post-pandemic period; in fact, many employees still want to work from home at least part of the time [1,14,43]. On the other hand, this result supporting hypothesis H6 can be explained by the TTF model. Thus, the hybrid model is the most desirable working model because it maximizes the alignment of tasks with available technologies, given that individuals can perform digitally compatible tasks remotely but can also have face-to-face interactions when necessary. Therefore, the hybrid working model increases both productivity and employee satisfaction.

In addition to theoretical perspectives, the results of this study have important implications for public policy, universities, and employers. The preference for the hybrid working model and the importance Romanian students give to digital skills indicate the relevance of reducing this type of inequality. Public policies should support investments in internet access, training programs, and strategies that allow all individuals to equally benefit from this way of working. Moreover, our findings suggest that universities should prepare current students, who will be the future employees, for hybrid work by developing both digital skills and cross-cutting skills such as adaptability, communication, and teamwork.

On the other hand, most of the students’ preference for the hybrid work model indicates that flexibility will have to be a defining feature of the human resources strategies that will be implemented in the post-pandemic labor market. Therefore, employers who offer flexible working conditions will be much more attractive to young people wishing to enter the labor market, while those who fail to adopt this flexibility will face significant challenges in recruiting young professionals. It is important to mention that human resources strategies must adapt to a new generation entering the labor market with different expectations in the context of the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. Furthermore, given that there are differences between the analyzed countries, strategies to support the hybrid work model must consider the particularities of each country’s labor market, education system, and cultural context, which influence young people’s expectations.

6. Conclusions

The aim of this study was to explore the perceptions and expectations of students from two Eastern European countries—Romania and Bulgaria—regarding working from home as an effect of the COVID-19 pandemic. The empirical results showed that there are significant differences between the two countries in terms of a number of aspects related to working from home. The efficiency of working from home compared to working at the workplace, as well as the most important advantages and disadvantages of working from home, are perceived differently by respondents in the two countries. Furthermore, Romanian respondents are more likely than Bulgarian respondents to believe that the way people work today is influenced by the pandemic. Additionally, respondents in the two countries have different perceptions of the most important skills in the post-pandemic labor market.

As for respondents’ future expectations, most want a hybrid working model, with no significant differences between the two countries. Furthermore, following a two-step cluster analysis based on their expectations, students were divided into three categories: Office-Centric Traditionalists, Flexibility-Seeking Hybrid Workers, and Remote-First Advocates.

In conclusion, although students in the two countries have different perceptions of working from home, they have similar expectations regarding future working arrangements, with the majority wanting a hybrid work style. This shows us that the COVID-19 pandemic has had a powerful effect on how people currently work, an effect that will also continue in the future.

This study has both theoretical and practical implications. In terms of theoretical implications, the study makes an important contribution to the literature by exploring students’ perceptions of working from home and their expectations regarding the post-pandemic labor market, with students representing an extremely important group that has not been sufficiently researched in this topic so far. Furthermore, the comparative analysis between the two countries provides important information on their differences and similarities, and can also contribute to future regional research, helping to fill the research gap on this topic. In terms of practical implications, the results of this study can guide higher education institutions as they adapt their educational strategies to the new context of accelerated digitization. The results can also help employers understand future employees’ expectations, and decision-makers can use them to develop policies that support young people’s transition into the post-pandemic labor market.

In this context, we believe that, to meet the needs of young people, universities and employers must take more concrete measures. Universities should offer training sessions on digital skills and time management, but also develop partnerships with employers to facilitate as many hybrid or remote internship opportunities as possible. On the other hand, employers should implement flexible work policies that meet young people’s expectations, invest in digital technologies, and develop various mentoring programs to support students and recent graduates and facilitate their entry into the labor market.

This study has some limitations that should be considered. First, using a non-probability sample of a relatively small size limits the ability to generalize the results. Another limitation is that no pilot test of the questionnaire was conducted, which could have improved the clarity and validity of some items. Furthermore, because the research is cross-sectional, it only captures the situation at a specific point in time. This prevents the analysis of how students’ perceptions evolve over the long term. Another limitation is the geographical context restricted to the two countries, which does not allow the conclusions to be extended to other countries, where different results may occur due to cultural and institutional particularities. However, as mentioned above, the study makes a relevant contribution to the literature and may contribute to future research directions.

Future research could focus on conducting follow-up studies to observe how students’ perceptions and expectations of remote and hybrid work evolve over time as labor market conditions change. In addition, applying qualitative methods such as interviews or focus groups could provide deeper insights into the motivations and experiences underlying the survey responses. Last but not least, expanding the analysis to more countries would provide a broader comparative perspective.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.P., A.B.A. and S.Z.; methodology, S.P., A.B.A. and S.Z.; software, S.Z. and A.B.A.; validation, S.P., A.B.A. and S.Z.; formal analysis, S.Z. and A.B.A.; investigation, A.B.A. and S.Z.; resources, S.P., A.B.A. and S.Z.; data curation, S.Z. and A.B.A.; writing—original draft preparation, S.P., A.B.A. and S.Z.; writing—review and editing, S.P., A.B.A. and S.Z.; visualization, A.B.A.; supervision, S.P.; funding acquisition, S.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable. This study involved no risks for participants. It is non-interventional, anonymous online survey of adult university students. No personal data (as defined by GDPR Art. 4(1)) were collected, and participation was voluntary with an information/consent statement at the beginning of the questionnaire. In Bulgaria, legal requirements for ethics approvals apply to medical scientific research on humans under the Health Act (e.g., Arts. 199–203) and to clinical trials under the Medicinal Products in Human Medicine Act and Order No. 31/2007 (Good Clinical Practice). These frameworks do not cover anonymous, non-medical social surveys. In Romania, ethics approvals are likewise mandated for clinical/biomedical research under Law No. 95/2006 and Ministry of Health Order No. 904/2006 (GCP), not for anonymous social questionnaires; those are governed at the institutional level. Based on the above, this study did not require Ethics Committee or Institutional Review Board approval under the applicable national frameworks.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

S1. Socio-demographic characteristics

- Which is your country of residence?

- Romania

- Bulgaria

- How old are you (in years)?

- What is your gender?

- Male

- Female

- I prefer not to say

- Which best describes the place where you live?

- Large City (with over 50,000 inhabitants)

- Small or medium-sized town (with between 5000 and 50,000 inhabitants)

- Very small town or village (with fewer than 5000 inhabitants)

- I prefer not to say

- What level of study are you enrolled in?

- Professional Bachelor’s degree

- Bachelor’s degree

- Master’s degree

- Doctoral degree

- What type of education are you currently enrolled in?

- Full-time education

- Part—time education

- Online/Distance learning

- Which is your main field of study?

- Economics

- Administration and Management

- Tourism

- Informatics and Computer Science

- Other (please specify)

- Were you a student during the pandemic (March 2020–May 2023)?

- Yes, during the entire period

- Yes, partially

- No, I become a student after the pandemic

- Did you work during the pandemic (March 2020–May 2023)?

- Yes, at the workplace

- Yes, remote

- Yes, hybrid (a combination of the two above)

- No, I did not work

- What is your current occupational status?

- Student—not currently working

- Student—working part-time

- Student—working full-time

- Student—working occasionally (e.g., freelance, internships, short-term projects)

- I am employed—no longer a student

- I am self-employed/freelancer

- Other (please specify):

- In which field do you work?

- Education and training

- Health and social work

- IT and software development

- Engineering and manufacturing

- Sales, retail and customer service

- Finance, banking, or insurance

- Public administration

- Communication, media, or creative industries

- Marketing, advertising, or PR

- Transport, logistics, or delivery services

- Tourism, hospitality, or events

- Agriculture or environmental services

- Legal services

- Research and development

- Construction or real estate

- Freelancing/project-based/other independent work

- I don’t work/Not applicable

- Other (please specify):

- What is the size of the organization you work for (based on the number of employees)?

- Micro-enterprise (1–9 employees)

- Small enterprise (10–49 employees)

- Medium enterprise (50–249 employees)

- Large enterprise (250+ employees)

- I don’t know

- Not applicable-I am self-employed

- I don’t currently work

- Where do you currently work from?

- Entirely on-site (at the workplace)

- One day from home, the rest on-site

- Two days from home, the rest on-site

- Three days from home, the rest on-site

- Four days from home, the rest on-site

- Fully from home (remote work only)

S2. Perceptions regarding working from home

- 14.

- In your opinion, working from home is:

- More efficient than working at the workplace

- As efficient as working at the workplace

- Less efficient than working at the workplace

- I can’t rate

- 15.

- Please indicate how much you agree or disagree with the following statements about working from home:

| Strongly Disagree | Somewhat Disagree | Neither Agree nor Disagree | Somewhat Agree | Strongly Agree | |

| 15.1. Working from home reduces daily stress | |||||

| 15.2. Working from home offers more balance between personal and professional life | |||||

| 15.3. Working from home negatively affects team communication | |||||

| 15.4. Working from home reduces chances of promotion/professional development | |||||

| 15.5. I would like my future job to allow working from home |

- 16.

- What are the main advantages of working from home for you? (choose maximum 3)

- Flexible schedule

- Saving commuting time

- Higher productivity

- Lower costs

- Personal space and quiet environment

- Other (please specify):

- 17.