Cultural Participation as a Pathway to Social Inclusion: A Systematic Review and Youth Perspectives on Disability and Engagement

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Ethical Considerations

2.3. Participants

2.4. Data Collection and Management

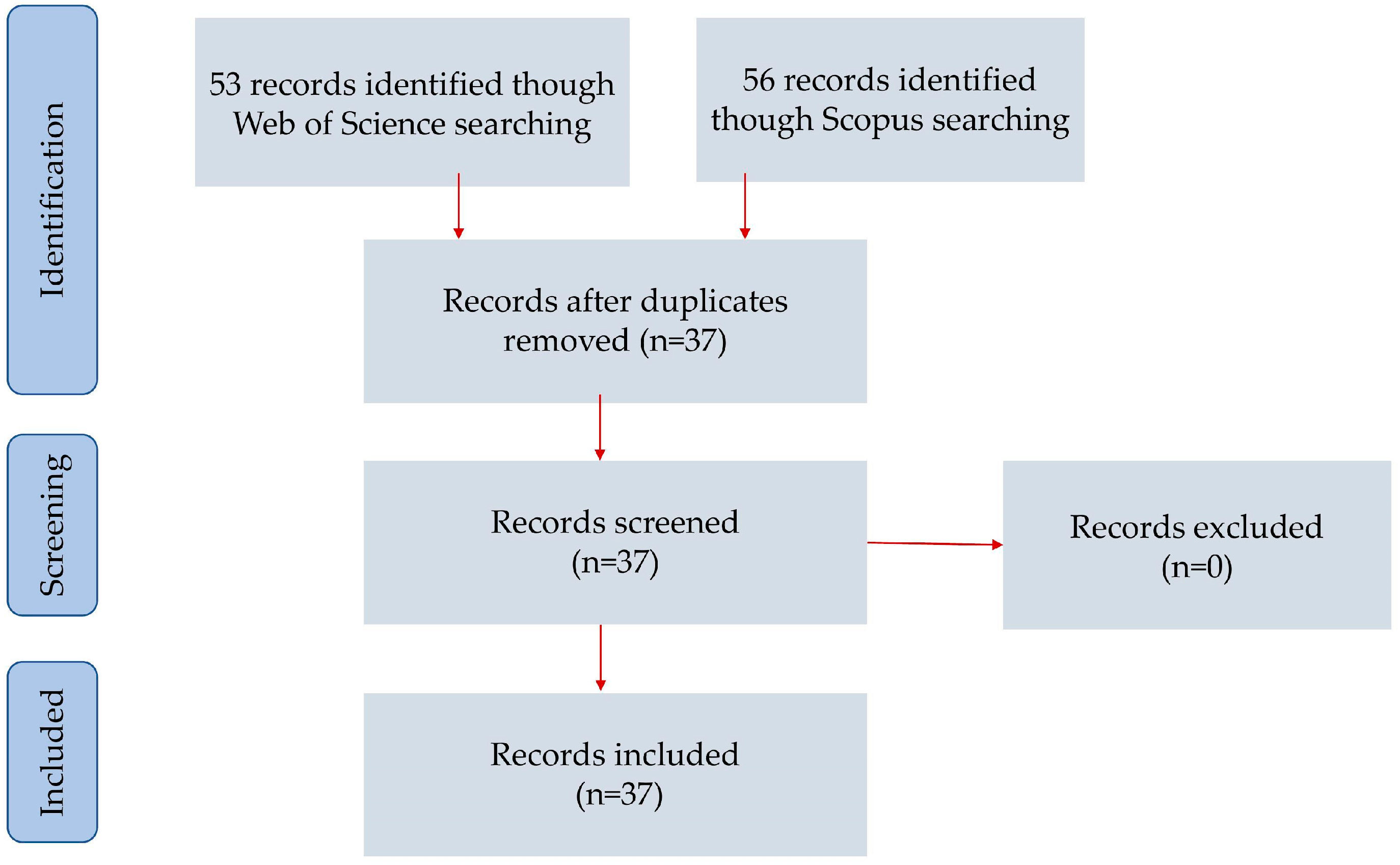

2.4.1. Phase 1: Systematic Review

2.4.2. Phase 2: Areas of Interest and Focus Groups

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Category 1: Health, Well-Being and Cultural Participation

- S1:

- “We have been able to do everything, and we know how to do it just like everyone else.”

- S3:

- “We have learned how to explain a monument. I thought it was going to be more difficult, but in the end I found it easy.”

- S8:

- “When I was preparing the summary, I was nervous at first, but I memorised it by reading it over and over again. It’s almost like I have a photographic memory, which helps me. It went well. I know I left out a lot of things I should have said, but it went well.”

- S2:

- “At first, I was a little embarrassed because I didn’t know what the situation would be like or who I would be with, even though I already knew some people. But now it’s like a gang, a normal group.”

3.2. Category 2: Access to Culture for All

- S5:

- “Make it easy to read so that we can all see it. This is because a person with a disability does not understand in the same way as someone without a disability. What you put...”

3.3. Category: Access to Culture for Persons with Disabilities

- S6:

- “This summer, I went out with my parents and helped my sister look for things. My sister was searching for things and I was looking on TikTok for the most famous places to visit in Andalusia.”

- S4:

- “I use my mobile phone a lot because it’s a way for me to communicate via video calls and WhatsApp, and to get the news. I mean, it’s essential for me. I need it. Without my mobile phone, I couldn’t live—I’d have to do.”

- S1:

- “Moovit, which I can use to navigate. I pay an annual subscription so it can tell me where the bus is in real time.”

- S7:

- “But I think what people should learn is how to stick around for a while and then leave. That’s what I’d like to learn. But it’s as if it hooks you...”

3.4. Category 4: Cultural Policies and Participation (Barriers and Facilitators)

- S4:

- “The minimum requirement would be subtitles; if an interpreter were also provided, that would be even better. There is always something missing.”

- S1:

- “you can make it more accessible so that everyone can access it as easily as possible in all environments. I mean, even a place to eat that is accessible. So, maybe we can talk about a restaurant that is not currently accessible, and discuss how we can make it accessible so that everyone can enjoy it, because it’s also part of tourism. It’s also part of culture, right?”

3.5. Category 5: Cultural Diversity and Participation

- S9:

- “Meeting people and their ideas, and learning how they approach issues such as accessibility. Getting to know a new place and meeting new people at the university and through the project is a gift.”

- S1:

- “Working with people with disabilities, with whom I had not worked before, has made me realise that we are all valuable, that we must be very inclusive, and that places should be more accessible. I notice this every time I go somewhere.”

- S7:

- “Because we are so involved in technology, we walk past the cathedral, for example, and don’t appreciate it.”

4. Findings and Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EU | European Union |

| ID | Intellectual Disability |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| PICO | Population, Intervention, Comparison and Outcomes |

| ASD | Autism Spectrum Disorder |

References

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). Social Inclusion: Theoretical and Conceptual Framework for the Generation of Indicators Related to the Sustainable Development Goals; United Nations Development Programme: Mexico City, Mexico, 2015; Available online: https://www.undp.org/sites/g/files/zskgke326/files/migration/mx/ODS-FINAL.pdf (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- Silver, H. The Contexts of Social Inclusion. SSRN Work. Pap. 2015, 144, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, K. Recognising Cultural Diversity: Implications for Persons with Disabilities. In Recognising Human Rights in Different Cultural Contexts; Kakoullis, E.J., Johnson, K., Eds.; Palgrave: Singapore, 2020; pp. 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Parliament Research Service (EPRS). Access to Culture in the European Union; Pasikowska-Schnass, M., Ed.; European Parliament Research Service: Brussels, Belgium, 2017; Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/thinktank/en/document/EPRS_IDA(2017)608631 (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Stenou, K.; United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. Universal Declaration on Cultural Diversity: A Vision, a Conceptual Platform, a Pool of Ideas for Implementation, a New Paradigm; United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization: Paris, France, 2022; Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000127162 (accessed on 29 May 2025).

- Bernardo, L.D.; Carvalho, C.R.A.D. The role of cultural engagement for older adults: An integrative review of scientific literature. Rev. Bras. Geriatr. Gerontol. 2020, 23, e190141. Available online: https://www.scielo.br/j/rbgg/a/bm4KygNqHKR8QF4QQFdGZbj/?lang=en (accessed on 16 July 2025). [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Sanidad, Política Social e Igualdad; Ministerio de Cultura. Estrategia Integral Española de Cultura para Todos: Accesibilidad a la Cultura Para las Personas con Discapacidad; Real Patronato sobre Discapacidad: Madrid, España, 2011; Available online: https://www.cedid.es/es/buscar/Record/180856 (accessed on 16 July 2025).

- United Nations. Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2006; Available online: https://www.un.org/disabilities/documents/convention/convoptprot-e.pdf (accessed on 11 July 2025).

- Kuppers, P. Studying Disability Arts and Culture: An Introduction; Bloomsbury Publishing: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. Global Education Monitoring Report 2020: Inclusion and Education—All Means All; United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization: Paris, France, 2020; Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000373718 (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Mesquita, S.; Carneiro, M.J. Accessibility of European museums to visitors with visual impairments. Disabil. Soc. 2016, 31, 373–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistical Office of the European Communities. People at Risk of Poverty or Social Exclusion [Tipslc10]; Statistical Office of the European Communities: Luxembourg, 2025; Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/tipslc10/default/table?lang=en&category=tips.tipspo (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística. Encuesta de Discapacidad, Autonomía Personal y Situaciones de Dependencia (EDAD 2008): Avance de Resultados; Instituto Nacional de Estadística: Madrid, Spain, 2008; Nota de prensa; Available online: https://ine.es/prensa/np524.pdf (accessed on 4 November 2008).

- Riddell, S.; Watson, N. Disability, Culture and Identity; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Puyalto, C.; Pallisera, M.; Fullana, J.; Vilá, M. Doing Research Together: A Study on the Views of Advisors with Intellectual Disabilities and Non-Disabled Researchers Collaborating in Research. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2016, 29, 146–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walmsley, J. Normalisation, emancipatory research and inclusive research in learning disability. Disabil. Soc. 2001, 16, 187–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiernan, C. Participation in research by people with learning disability: Origins and issues. Br. J. Learn. Disabil. 1999, 27, 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdugo, M.A.; Navas, P.; Gómez, L.E.; Schalock, R.L. The concept of quality of life and its role in enhancing human rights in the field of intellectual disability. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2012, 56, 1036–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hewitt, O.; Langdon, P.E.; Tapp, K.; Larkin, M. A systematic review and narrative synthesis of inclusive health and social care research with people with intellectual disabilities: How are co-researchers involved and what are their experiences? J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2023, 36, 681–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabirón, F. Métodos de Investigación Etnográfica en Ciencias Sociales; Mira: Madrid, España, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- González, J.; Buñuel, J.C.; Aparicio, M. Listas guía de comprobación de revisiones sistemáticas y metaanálisis: Declaración PRISMA. Evid. Pediatr. 2011, 7, 20. [Google Scholar]

- Kaehne, A.; O’Connell, C. Focus groups with people with learning disabilities. J. Intellect. Disabil. 2010, 14, 133–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogel-Salazar, R. El grupo de discusión: Revisión de premisas metodológicas. Cinta Moebio 2018, 63, 274–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; The PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Int. J. Surg. 2010, 8, 336–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angrosino, M. Doing Ethnographic and Observational Research; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Thomas, J.; Chandler, J.; Cumpston, M.; Li, T.; Page, M.J.; Welch, V.A. (Eds.) Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, Version 6.5 (Updated August 2024); Cochrane: London, UK, 2024; Available online: https://www.cochrane.org/authors/handbooks-and-manuals/handbook/current (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- McKenzie, J.E.; Brennan, S.E.; Ryan, R.E.; Thomson, H.J.; Johnston, R.V.; Thomas, J. Chapter 3: Defining the criteria for including studies and how they will be grouped for the synthesis. In Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, Version 6.5; Higgins, J.P.T., Thomas, J., Chandler, J., Cumpston, M., Li, T., Page, M.J., Welch, V.A., Eds.; Cochrane: London, UK, 2024; Available online: https://www.cochrane.org/authors/handbooks-and-manuals/handbook/current/chapter-03 (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- De Munck, V.C.; Sobo, E.J. Using Methods in the Field: A Practical Introduction and Casebook; AltaMira Press: Walnut Creek, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Stake, R.E. The Art of Case Study Research; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Jachyra, P.; Atkinson, M.; Washiya, Y. “Who are you, and what are you doing here”: Methodological considerations in ethnographic Health and Physical Education research. Ethnogr. Educ. 2015, 10, 242–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitzinger, J. Qualitative Research: Introducing Focus Groups. BMJ 1995, 311, 299–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mays, N.; Pope, C. Qualitative Research: Rigour and qualitative research. BMJ 1995, 311, 109–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbour, R. Doing Focus Groups; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Sánchez, R.; Víquez-Calderón, D. Los grupos de discusión como metodología adecuada para estudiar las cogniciones sociales. Actual. En Psicol. 2010, 23, 87–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Nicácio, R.T.; Barbosa, R.L.L. Understanding higher education teaching, learning and evaluation: A qualitative analysis supported by ATLAS.ti. In Computer Supported Qualitative Research—Proceedings of the Second International Symposium on Qualitative Research, East Hanover, NJ, USA, 27 June–29 July 2018; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 393–399. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Flick, U. An Introduction to Qualitative Research, 6th ed.; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Giovanis, E. Participation in Socio-Cultural Activities and Subjective Well-Being of Natives and Migrants: Evidence from Germany and the UK. Int. Rev. Econ. 2023, 68, 423–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Martínez, J.; Takeuchi, D.; Martínez-Martínez, O.A.; Lombe, M. The Role of Cultural Participation on Subjective Well-Being in Mexico. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2021, 16, 1321–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Løkken, B.I.; Merom, D.; Sund, E.R.; Krokstad, S.; Rangul, V. Association of Engagement in Cultural Activities with Cause-Specific Mortality Determined through an Eight-Year Follow-Up: The HUNT Study, Norway. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0248332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nappo, N.; Fiorillo, D. Volunteering and Self-Perceived Individual Health: Cross-Country Evidence from Nine European Countries. Int. J. Soc. Econ. 2020, 47, 285–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agovino, M.; Crociata, A.; Quaglione, D.; Sacco, P.; Sarra, A. Good Taste Tastes Good: Cultural Capital as a Determinant of Organic Food Purchase by Italian Consumers: Evidence and Policy Implications. Ecol. Econ. 2017, 141, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, G.T. Small and Slow Is Beautiful: Well-Being, ‘Socially Connective Retail’ and the Independent Bookshop. Soc. Cult. Geogr. 2017, 18, 573–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Currie, C.L.; Wild, T.C.; Schopflocher, D.P.; Laing, L.; Veugelers, P. Illicit and Prescription Drug Problems among Urban Aboriginal Adults in Canada: The Role of Traditional Culture in Protection and Resilience. Soc. Sci. Med. 2013, 88, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adamsen, C.; Manson, S.M.; Jiang, L. The Association of Cultural Participation and Social Engagement with Self-Reported Diagnosis of Memory Problems among American Indian and Alaska Native Elders. J. Aging Health 2021, 33 (Suppl. S7–S8), 60S–67S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocozza, S.; Sacco, P.L.; Matarese, G.; Maffulli, G.D.; Maffulli, N.; Tramontano, D. Participation to Leisure Activities and Well-Being in a Group of Residents of Naples-Italy: The Role of Resilience. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Węziak-Białowolska, D. Attendance of Cultural Events and Involvement with the Arts—Impact Evaluation on Health and Well-Being from a Swiss Household Panel Survey. Public Health 2016, 139, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuypers, K.; Krokstad, S.; Holmen, T.L.; Knudtsen, M.S.; Bygren, L.O.; Holmen, J. Patterns of Receptive and Creative Cultural Activities and Their Association with Perceived Health, Anxiety, Depression and Satisfaction with Life among Adults: The HUNT Study, Norway. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2012, 66, 698–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovanis, E.; Akdede, S.H. Well-Being of Old Natives and Immigrants in Europe: Does the Socio-Cultural Integration Matter? Int. J. Happiness Dev. 2022, 7, 291–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Campen, C.; Iedema, J. Are Persons with Physical Disabilities Who Participate in Society Healthier and Happier? Structural Equation Modelling of Objective Participation and Subjective Well-Being. Qual. Life Res. 2007, 16, 635–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornasari, F. Social Inclusion and Museum. Communities, Places, Narratives. Eur. J. Creat. Pract. Cities Landsc. 2020, 3, 159–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilroy, J.; Emerson, E. Australian Indigenous Children with Low Cognitive Ability: Family and Cultural Participation. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2016, 56, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narciso, D.; Pádua, L.; Adão, T.; Peres, E.; Magalhães, L. Mixar Mobile Prototype: Visualizing Virtually Reconstructed Ancient Structures In Situ. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2015, 64, 852–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubiel, M. National Theatre in My Kitchen: Access to Culture for Blind People in Poland During COVID-19. Soc. Incl. 2023, 11, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabatini, S.; Martyr, A.; Gamble, L.D.; Jones, I.R.; Collins, R.; Matthews, F.E.; Knapp, M.; Thom, J.M.; Henderson, C.; Victor, C.; et al. Are Profiles of Social, Cultural, and Economic Capital Related to Living Well with Dementia? Longitudinal Findings from the IDEAL Programme. Soc. Sci. Med. 2023, 317, 115603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gigerl, M.; Sanahuja-Gavaldà, J.M.; Petrinska-Labudovikj, R.; Moron-Velasco, M.; Rojas-Pernia, S.; Tragatschnig, U. Collaboration between Schools and Museums for Inclusive Cultural Education: Findings from the INARTdis-Project. Front. Educ. 2022, 7, 979260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Pineda, D.R.; López-Hernández, O. Experiencias de Artistas con Discapacidad frente a la Promoción de la Inclusión Social. Arte Individuo Soc. 2020, 32, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šubic, N.; Ferri, D. National Disability Strategies as Rights-Based Cultural Policy Tools. Int. J. Cult. Policy 2023, 29, 467–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leahy, A.; Ferri, D. Barriers and Facilitators to Cultural Participation by People with Disabilities: A Narrative Literature Review. Scand. J. Disabil. Res. 2022, 24, 68–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theben, A.; Aranda, D.; Lupiáñez Villanueva, F.; Porcu, F. Participación y Ciudadanía Activa de los Jóvenes a Través de Internet y las Redes Sociales: Un Estudio Internacional. Bid-Textos Univ. Bibl. Doc. 2021, 46, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, H.W.; Fancourt, D. Do Socio-Demographic Factors Predict Children’s Engagement in Arts and Culture? Comparisons of In-School and Out-of-School Participation in the Taking Part Survey. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0246936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giovanis, E.; Akdede, S.H. Integration Policies in Spain and Sweden: Do They Matter for Migrants’ Economic Integration and Socio-Cultural Participation? SAGE Open 2021, 11, 21582440211054476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iñiguez-Berrozpe, T.; Elboj-Saso, C.; Flecha, A.; Marcaletti, F. Benefits of Adult Education Participation for Low-Educated Women. Adult Educ. Q. 2020, 70, 64–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallmann, K.; Artime, C.M.; Breuer, C.; Dallmeyer, S.; Metz, M. Leisure Participation: Modelling the Decision to Engage in Sports and Culture. J. Cult. Econ. 2017, 41, 467–487. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/48698175 (accessed on 15 July 2025). [CrossRef]

- Gohn, M.G. Teorias sobre a Participação Social: Desafios para a Compreensão das Desigualdades Sociais. Cad. CRH 2019, 32, 63–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAndrew, S.; Richards, L. Religiosity, Secular Participation, and Cultural Socialization: A Case Study of the 1933–1942 Urban English Cohort. J. Sci. Study Relig. 2020, 59, 247–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campagna, D.; Caperna, G.; Montalto, V. Does Culture Make a Better Citizen? Exploring the Relationship Between Cultural and Civic Participation in Italy. Soc. Indic. Res. 2020, 149, 657–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraaykamp, G.; Notten, N.; Bekhuis, H. Highbrow Cultural Participation of Turks and Moroccans in the Netherlands: Testing an Identification and Social Network Explanation. Cult. Trends 2015, 24, 286–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillenburger, K.; McKerr, L.; Jordan, J.A.; Devine, P.; Keenan, M. Creating an Inclusive Society… How Close Are We in Relation to Autism Spectrum Disorder? A General Population Survey. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2015, 28, 330–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tawagi, A.L.; Mak, A.S. Cultural Inclusiveness Contributing to International Students’ Intercultural Attitudes: Mediating Role of Intergroup Contact Variables. J. Community Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2015, 25, 340–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghadam, V.M.; Senftova, L. Measuring Women’s Empowerment: Participation and Rights in Civil, Political, Social, Economic, and Cultural Domains. Int. Soc. Sci. J. 2005, 57, 389–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, P.A. Black Cultural Advancement: Racial Identity and Participation in the Arts among the Black Middle Class. Ethn. Racial Stud. 2010, 33, 272–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porras Montes, A.; Huete García, A. Juventud Con Discapacidad en España 2024. Informe de Situación; CERMI—Comité Español de Representantes de Personas con Discapacidad: Madrid, España, 2024; Available online: https://diario.cermi.es/file/juventud-con-discapacidad-en-espana-2024-informe-de-situacion (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Coleman, J. Social Capital in the Creation of Human Capital. Am. J. Sociol. 1988, 94, S95–S120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, R.D. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community; Simon & Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

| Categories | Records Included |

|---|---|

| Health and/or Well-Being and Cultural Participation | [6,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49] |

| Access to culture for all | [50,51,52] |

| Access to culture for people with disabilities | [53,54,55,56] |

| Cultural policies and participation (barriers and facilitators) | [57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64] |

| Cultural diversity and participation | [65,66,67,68,69,70,71] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sáez-Velasco, S.; Merino-Orozco, A.; Di Giusto-Valle, C.; Mercado-Val, E.; Pérez De Albéniz-Garrote, G.; Delgado-Benito, V.; Medina-Gómez, B. Cultural Participation as a Pathway to Social Inclusion: A Systematic Review and Youth Perspectives on Disability and Engagement. Societies 2025, 15, 288. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15100288

Sáez-Velasco S, Merino-Orozco A, Di Giusto-Valle C, Mercado-Val E, Pérez De Albéniz-Garrote G, Delgado-Benito V, Medina-Gómez B. Cultural Participation as a Pathway to Social Inclusion: A Systematic Review and Youth Perspectives on Disability and Engagement. Societies. 2025; 15(10):288. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15100288

Chicago/Turabian StyleSáez-Velasco, Sara, Abel Merino-Orozco, Cristina Di Giusto-Valle, Elvira Mercado-Val, Gloria Pérez De Albéniz-Garrote, Vanesa Delgado-Benito, and Begoña Medina-Gómez. 2025. "Cultural Participation as a Pathway to Social Inclusion: A Systematic Review and Youth Perspectives on Disability and Engagement" Societies 15, no. 10: 288. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15100288

APA StyleSáez-Velasco, S., Merino-Orozco, A., Di Giusto-Valle, C., Mercado-Val, E., Pérez De Albéniz-Garrote, G., Delgado-Benito, V., & Medina-Gómez, B. (2025). Cultural Participation as a Pathway to Social Inclusion: A Systematic Review and Youth Perspectives on Disability and Engagement. Societies, 15(10), 288. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15100288