Abstract

Soft skills are increasingly recognised as decisive factors for employability and career advancement in the global labour market. This study examines their role in the professional trajectories of university graduates in Ecuador, analysing both the competencies supplied by higher education and the structural demand of the labour market. Based on institutional surveys applied to 3358 graduates from the Salesian Polytechnic University (Cuenca campus), the results show that more than of graduates remain in operational positions, while only reach tactical or managerial levels. To address this phenomenon, five key soft skills—leadership, effective communication, teamwork, problem-solving, and adaptability—were evaluated through a structured questionnaire using Likert-type items. The findings reveal a persistent concentration of professionals in lower organisational levels and heterogeneous perceptions of the applicability of academic training. These outcomes highlight both individual skill gaps and structural limitations of the Ecuadorian labour market, such as the scarcity of managerial positions and the prevalence of family-based business structures. In response, the study proposes a sector-based curricular improvement strategy that systematically incorporates soft skills into university programmes, differentiated by economic sectors such as education, health, commerce, public administration, industry, and primary activities. Grounded in empirical evidence, this approach provides a practical framework to enhance graduates’ career progression, foster more equitable professional mobility, and strengthen the relevance of higher education. The model can be replicated across other Latin American universities facing similar challenges, while also aligning with international standards for competency-based education.

1. Introduction

In the current context, characterized by digital transformation and the constant evolution of the labour market, soft skills have become a central factor for the employability and professional projection of university graduates [1,2,3,4,5]. These competencies, in synergy with technical knowledge, shape a more competitive professional profile, adaptable to the changing demands of different economic sectors. Soft skills comprise a broad and heterogeneous set of non-technical competencies that include effective communication, leadership, teamwork, adaptability, problem-solving, and conflict management. Their definition, however, remains complex and subject to debate, as they encompass not only skills but also attitudes, values, and personal attributes [6,7,8,9,10,11].

Despite this conceptual ambiguity, the literature agrees that they represent transversal competencies, transferable across different contexts, and are essential for employability, active citizenship, and lifelong learning [8,12,13,14]. In this study, soft skills are operationalised through specific dimensions that include leadership, communication, teamwork, adaptability, and problem-solving, in line with international frameworks on professional competencies.

The relevance of these competencies is widely recognised in the business field. International corporations such as Toyota and General Motors, as well as accrediting bodies such as ABET (Accreditation Board for Engineering and Technology), prioritise in their recruitment and performance evaluation processes capacities such as critical thinking, emotional regulation, adaptability, effective communication, and decision-making in highly complex contexts [9,15,16,17]. Corporate reports indicate that more than of the criteria used to promote talent from operational positions to middle and senior management are based on these competencies, even above sustained technical performance. This evidence reinforces the premise that soft skills are an indispensable requirement for leadership, innovation, and productivity in increasingly competitive organisational environments.

In Latin America, and particularly in Ecuador, this challenge presents specific characteristics. Institutional data from the Salesian Polytechnic University (UPS) show that among graduates registered since 2013, only occupy tactical or managerial positions, while more than remain in operational roles. This finding suggests a gap in the development of transversal competencies that facilitate advancement to positions of greater responsibility. Nevertheless, it must also be acknowledged that the limited generation of managerial positions in the Ecuadorian labour market, along with the prevalence of family-based enterprises in which leadership roles are often reserved for close circles of trust, restrict professional mobility even for graduates with strong soft skills. Therefore, the explanation of this phenomenon must simultaneously consider the supply of competencies and the structural demand of the labour market.

This problem is not exclusive to Ecuador. Comparative studies in Argentina and Colombia indicate that most university graduates remain in technical roles without accessing leadership positions, due to the scarce incorporation of transversal competencies into curricula [18,19,20,21]. Previous research has also highlighted that the lack of effective communication, leadership, conflict resolution, and critical thinking constitutes one of the main barriers to professional progression, even when strong technical training is present [22,23].

The convergence of findings across different countries reinforces the need to rethink Latin American university curricula by systematically integrating soft skills to foster sustainable professional trajectories. However, the review of curricula in Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) in the region reveals significant gaps in pedagogical methodologies that allow these skills to be evaluated and developed in a structured and verifiable manner [24,25,26,27]. The absence of robust assessment mechanisms generates uncertainty regarding the relevance of university education in relation to labour market demands and pressures universities to design innovative strategies for training holistic professionals.

The present study examines the gaps between university academic training and the transversal competencies demanded by the labour market in Ecuador. Based on institutional survey data collected from 3358 UPS graduates, complemented by interviews with employers and key stakeholders, we propose a strategy for curricular alignment that identifies the priority soft skills for each economic sector and their relationship with graduates’ organisational positioning.

The aim is to generate useful evidence to highlight current employability challenges, guide the redesign of academic programmes according to the productive context, and strengthen the connection between universities and the labour market. This article seeks to answer the following research question: To what extent does the academic training of UPS graduates provide the soft skills required for employability and professional advancement in the Ecuadorian labour market? Moreover, this issue is framed within the guidelines of the Council of Higher Education (CES), the Council for Quality Assurance in Higher Education (CACES) [28], and the National System for Admission and Leveling (SNNA), ensuring coherence with current national educational policies.

2. Methodology

2.1. Focus

This study adopts a quantitative, descriptive, and cross-sectional approach, aimed at analysing university graduates’ perceptions of the applicability of their academic training in the labour market, with a particular emphasis on transversal competencies (soft skills). The central methodological objective is to examine the extent to which skills such as leadership, communication, teamwork, problem-solving, and adaptability—acquired during university education—are related to labour market insertion and to the occupation of hierarchical levels (operational, tactical, and managerial).

The research also considers the distribution of participants according to the economic sector in which they are employed, which allows the identification of general patterns linking academic preparation with current professional practice.

2.2. Data Collection Instrument

For data collection, a structured questionnaire was employed, designed on the basis of previous studies [23,24,25,26,29]. The instrument was organised into three complementary blocks.

The first block, sectoral and organisational classification, gathered information on the economic sector in which participants are employed (primary, secondary, or tertiary) and the hierarchical level reached within their organisation (operational, tactical, or managerial).

The second block, perception of the application of academic training, assessed the extent to which participants apply the knowledge acquired during their degree in their professional practice, using a four-point Likert scale ranging from “Strongly agree” to “Strongly disagree” [30,31].

Finally, the third block, development of transversal competencies (soft skills), examined graduates’ self-assessment across five key dimensions—leadership, effective communication, teamwork, problem-solving, and adaptability.

Each dimension was evaluated through five-point Likert items adapted from validated instruments in previous studies [31]. Examples of these items include “The training I received strengthened my leadership capacity to coordinate teams” and “My degree enabled me to develop effective communication skills in professional contexts.” This block made it possible to analyse the relationship between graduates’ perception of competence development and the hierarchical level attained in the labour market.

Together, the first two blocks, along with the specific section on soft skills, provide an integrated overview of graduates’ professional trajectories and the relevance of their academic training. Table 1 summarises this information, showing the sectoral distribution, the hierarchical level reached, and the assessment of transversal competencies.

Table 1.

Sectoral distribution of UPS graduates—Cuenca Campus (2013–2021), according to organisational level and perception of the application of their profession: shows the frequency and percentage of graduates by economic sector (primary, secondary, and tertiary), their location within the business structure (operational, tactical, and managerial) and their degree of agreement regarding the applicability of university education in their work environment.

2.3. Participants

The study population consisted of 6,638 graduates registered since 2013 at the Salesian Polytechnic University (UPS), Cuenca campus. Of this total, 3358 responded to the institutional follow-up questionnaire, representing a response rate of . This sample constitutes the analytical base of the present study and provides a sufficient volume of cases to ensure the statistical robustness of the results.

UPS offers undergraduate programmes in diverse areas of knowledge, including Business Administration, Accounting and Auditing, Economics, Architecture, Biotechnology, Biomedicine, Law, Anthropology, Intercultural Bilingual Education, Theology, and Multimedia Design. This academic diversity is relevant because it differentially shapes professional trajectories: graduates from management- and business-related fields tend to project themselves more quickly into leadership positions, whereas those from technical, scientific, or social disciplines usually begin in operational or intermediate roles, with longer processes of career advancement. Therefore, not all graduates face the same opportunities to attain managerial positions in the short term, which constitutes an antecedent variable influencing the relationship between soft skills and organisational position.

Moreover, the data analysed correspond to the period 2013–2021, which implies the participation of cohorts with varying professional trajectories. Naturally, a recent graduate (for example, from 2021) has fewer chances of having reached a managerial position compared to a graduate from 2013, with almost a decade of accumulated experience. This temporal difference represents a contextual factor that must be considered when interpreting the results.

Finally, a central variable in the analysis is the organisational level occupied by participants (operational, tactical, or managerial), as it allows assessing the correspondence between the academic training received and their effective insertion into the labour market.

Ethical Consideration on the Data Source

The data used in this study were obtained from the institutional graduate follow-up system of the Salesian Polytechnic University (UPS), which periodically administers structured surveys for academic and quality assurance purposes. The information collected corresponds to voluntary responses from participants and was anonymised by the institution prior to delivery for analysis, thereby guaranteeing confidentiality and compliance with current ethical standards.

According to the UPS Policy for the Protection and Use of Personal Data (Resolution No. 128-104-2023-04-19), the use of information for statistical and academic research purposes does not require the explicit authorisation of data subjects, provided that ethical, confidential, and limited use of the data is ensured. For this reason, the study was exempt from review by an ethics committee, as it did not involve direct intervention with individuals or the handling of identifiable sensitive information.

The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and international guidelines on ethics in educational research, ensuring that the results are used exclusively for academic purposes and for the improvement of higher education quality.

3. Results

3.1. Sectoral Analysis of the Professional Practice of Graduates

To better understand the relationship between university academic training and professional practice, we analysed graduates’ outcomes across the three main economic sectors: primary, secondary, and tertiary. This analysis focused on three key dimensions: (i) labour market insertion, defined as the proportion of graduates actively employed in each sector; (ii) professional performance, referring to the functions graduates perform in relation to the competencies they acquired during their studies; and (iii) organisational positioning, determined by the hierarchical level they have reached within the workplace (operational, tactical, or managerial).

This structured approach not only quantifies graduates’ presence in the different productive sectors but also evaluates the quality of their participation and their real opportunities for professional development. In addition, it helps identify structural barriers, areas for improvement, and occupational trends that directly shape labour mobility and the construction of sustainable career paths. The following sections present the detailed analysis by economic sector, based on these three dimensions.

3.1.1. Primary Sector

The primary sector which includes agriculture, livestock, forestry, fishing, and mining shows only marginal participation from university graduates. According to the data analysed, fewer than of the surveyed graduates report employment in this sector, which underscores the weak link between academic training and the productive dynamics of the country’s rural and extractive activities.

This pattern is consistent with other Latin American contexts, where the primary sector remains one of the least technologised and absorbs very little university-trained talent [32,33,34,35,36,37]. In the few cases where insertion does occur, graduates usually take on operational functions with limited access to management or planning roles. This situation suggests an underutilisation of the competencies they acquired during their studies.

Two main factors explain this scenario. First, a curricular disconnection: degree programmes do not sufficiently address sector-specific challenges such as environmental sustainability, agro-industrial innovation, or territorial management. Second, the lack of institutional and public policies that encourage professional participation in these environments limits the sector’s consolidation as a viable option for graduate employment.

Nevertheless, the primary sector remains a strategic field with high potential for transformation. Incorporating soft skills such as adaptability, community leadership, and intercultural communication [33,34,38] can significantly strengthen the professional role in rural contexts, which are often characterised by weak or undefined organisational structures. More contextualised, interdisciplinary, and territory-oriented training would not only expand employment opportunities in this sector but also contribute more effectively to the country’s sustainable development.

3.1.2. Secondary Sector

The secondary sector which includes manufacturing, construction, energy generation, and other transformation processes represents a moderate space of employment for university graduates. Around of the surveyed graduates work in this sector, primarily in fields related to engineering, industrial maintenance, and operational management.

Although participation is higher than in the primary sector, most graduates remain concentrated in operational and tactical positions, with very limited access to managerial roles. This pattern reflects structural barriers to upward mobility, which can be explained by three interrelated factors.

First, technical degree programmes still prioritise disciplinary content without systematically integrating transversal competencies such as leadership, effective communication, or conflict resolution. As noted in [36,37], this omission reduces graduates’ ability to take on strategic responsibilities in dynamic and highly demanding industrial environments.

Second, many industries operate within rigid hierarchical structures, where access to decision-making positions depends more on seniority or internal tenure than on demonstrated competencies. This organisational logic—commonly described as hierarchical capitalism [39,40]—restricts upward mobility for young professionals, even when they possess solid academic training.

Third, the weak connection between universities and industrial firms contributes to outdated curricula and training that is disconnected from the sector’s actual needs. As highlighted by [41,42,43,44,45,46,47], this gap limits knowledge transfer and hinders the incorporation of high value-added professional profiles into the industrial workforce.

Despite these challenges, the secondary sector offers significant opportunities for innovation, technological application, and continuous process improvement. To take advantage of this potential, higher education institutions need to strengthen the development of interpersonal and organisational soft skills and implement strategies such as internships, dual training programmes, and institutional partnerships with companies. These initiatives would better prepare students to assume leadership roles and facilitate their transition into strategic functions within industrial structures.

3.1.3. Tertiary Sector

The tertiary sector which includes service activities such as education, health, commerce, public administration, finance, and tourism—constitutes the main area of employment for university graduates. More than of the surveyed graduates work in this sector, with education , public administration , commerce , and health standing out as the most significant subsectors. This high participation suggests a notable alignment between the university’s academic offerings and local labour market demands.

In contrast to the limited presence in the primary sector and the moderate participation in the secondary sector, the tertiary sector demonstrates a much greater capacity to absorb university-trained profiles, particularly in teaching, public management, professional services, and customer-oriented activities. However, the analysis also shows that most graduates remain in operational or tactical positions, with restricted access to managerial roles. This indicates broad inclusion but limited vertical development—a phenomenon that several studies describe as partial integration within organisational structures [41,42,43].

Three interrelated factors help explain this pattern. First, service environments demand relational competencies such as effective communication, empathy, leadership, and conflict resolution [48], which are essential for assuming strategic responsibilities. When these soft skills are absent or underdeveloped, graduates struggle to progress into coordination or leadership roles. Second, subsectors such as commerce and public administration are characterised by high staff turnover, temporary contracts, and limited internal promotion, which undermine the consolidation of sustainable career paths. Third, despite these limitations, the tertiary sector represents a platform with high social impact potential, particularly in areas such as health and education, where professional work can directly benefit vulnerable communities.

In sum, while this sector concentrates the largest share of graduates, it also requires stronger training in socio-emotional skills, leadership, team management, and decision-making. Universities should therefore implement institutional policies that foster entrepreneurship, professional mobility, and progressive access to higher hierarchical levels within the service sector.

3.1.4. Organizational Position and Perceived Applicability

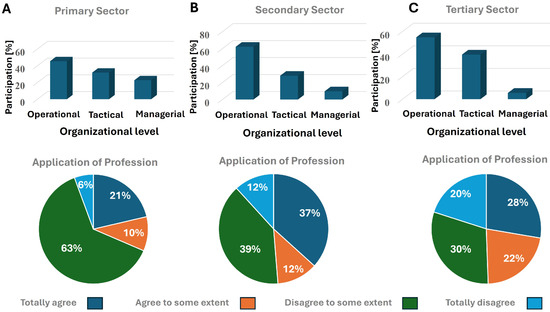

Figure 1 compares graduates’ organisational level with their perception of the applicability of academic training, differentiated by economic sector: primary (A), secondary (B), and tertiary (C).

Figure 1.

Organizational level and perceived applicability: (A) Primary sector; (B) Secondary sector; (C) Tertiary sector.

In the primary sector (Figure 1A), most graduates concentrate in operational roles and tactical roles , with minimal presence in managerial positions. However, perceptions of academic training are predominantly negative: of respondents strongly disagreed with the statement “I apply my profession”, while partially disagreed. These results indicate a marked underutilisation of academic knowledge and soft skills, most likely related to the sector’s low level of technological development and its limited demand for university-trained professionals.

In the secondary sector (Figure 1B), around of graduates work in operational positions, in tactical roles, and only in managerial roles. Perceptions of applicability are divided: reported fully applying their training, while stated that they do not apply it. This disparity reflects heterogeneous experiences within the industrial sector, where some graduates achieve alignment between their academic profile and professional tasks, while others face a mismatch between training and assigned responsibilities.

In the tertiary sector (Figure 1C), which employs the largest share of graduates, remain in operational positions and in tactical positions, with only a small fraction in leadership roles. Perceptions of applicability are also fragmented: reported not applying what they learned, while strongly agreed that they do. This heterogeneous pattern reflects the diversity of subsectors (education, health, commerce, etc.), which present highly variable demands and working conditions.

Taken together, these findings confirm a structural trend: access to employment does not necessarily guarantee meaningful or adequate professional insertion. The high concentration of graduates in lower hierarchical levels, combined with negative or inconsistent perceptions of the utility of academic training, highlights the urgent need to rethink curricula.

Higher education institutions must foster programmes more closely connected to sectoral contexts and focused on the development of soft skills and transferable competencies, in order to promote professional trajectories that are more meaningful, sustainable, and aligned with expected graduate profiles.

3.2. Sectoral Analysis of Soft Skills and Organizational Mobility

The study highlights a persistent structural trend: a large proportion of graduates remain in operational positions, with limited participation in tactical or managerial roles.

This situation appears consistently across strategic sectors such as education, health, commerce, public administration, industry, and even primary activities. Labour market insertion, therefore, does not always translate into upward professional development, revealing a gap between graduate profiles and the actual demands of the productive environment—particularly those that extend beyond technical knowledge.

In this context, strengthening soft skills emerges as a structural requirement for facilitating organisational advancement. These transversal, contextualised, and progressive competencies enable professionals to take on functions related to leadership, coordination, decision-making, and adaptation to dynamic environments [49,50,51,52].

From a conceptual perspective, no single or universally accepted taxonomy exists for these skills. In the literature, they appear under different labels—non-technical skills, transferable skills, interpersonal skills, or employability skills—which reflects their versatile and highly adaptable nature. Their multicomponent character also becomes evident in sectoral expression: certain competencies gain more importance depending on the economic sector, equipping professionals to evolve from operational roles to strategic responsibilities.

The study identifies significant differences among the sectors with the highest graduate participation, with education , public administration , and commerce standing out, followed by lower representation in health and the primary sector . Each of these areas requires specific competencies that reflect graduates’ adaptation to diverse professional contexts. In the field of education, essential skills include effective communication, pedagogical leadership, conflict resolution, and collegial decision-making, while in the health sector, ethical leadership, time management, empathy, and emotional regulation are particularly relevant, as they are indispensable in high-pressure environments. In commerce, the demand centers on customer orientation, persuasive communication, problem-solving agility, and resilience, competencies that are critical for progression into supervisory or operational logistics roles. In public administration, evidence-based decision-making, regulatory adaptability, professional ethics, and institutional leadership are highly valued, as they are fundamental for occupying mid-level or managerial positions. Likewise, the secondary or industrial sector requires technical problem-solving, leadership in production processes, openness to technological innovation, and collaborative work in structured environments. Finally, although less represented, the primary sector calls for autonomy, resilience, community leadership, and independent decision-making, particularly in connection with rural development and sustainable agro-industrial projects.

It is important to note that soft skills are not restricted to the interpersonal sphere. They also include intrapersonal dimensions (self-management, change management), cognitive dimensions (critical thinking, informed judgement), and affective dimensions (empathy, active listening), all of which show high transferability across diverse work contexts.

Therefore, their systematic integration into university curricula must go beyond theoretical inclusion. Active methodologies, simulations, case studies, interdisciplinary projects, and performance-based assessments are required to ensure gradual and measurable development of these competencies. Such a training strategy would help reduce the over-concentration of graduates in operational functions, promoting more dynamic and sustainable professional trajectories aligned with the demands of the twenty-first century.

3.3. Projection Towards Curricular Improvement

Soft skills constitute a key factor in the processes of labour market insertion and professional progression for university graduates, regardless of the economic sector in which they are employed. Multiple studies confirm that competencies such as leadership, teamwork, effective communication, problem-solving, adaptability, and evidence-based decision-making are highly valued and can facilitate the transition from operational functions to tactical or leadership positions. Nevertheless, this relationship must be interpreted with caution, since the data from this study do not allow us to establish a direct causal link between the lack of these competencies and the low proportion of graduates in managerial roles. Structural factors of the labour market—such as the limited generation of managerial positions, the prevalence of family-based enterprises, and sectoral restrictions that reduce the availability of leadership roles—also play a decisive role.

This phenomenon, clearly evidenced at the Salesian Polytechnic University, Cuenca campus, does not represent an isolated case. On the contrary, it reflects a broader challenge across many higher education institutions in Latin America, where curricula still prioritize technical components while neglecting the systematic and progressive development of transversal competencies as an integral part of graduate profiles. The sectoral analysis reveals differentiated patterns regarding the types of soft skills that support professional advancement. In particular, interpersonal skills—such as communication, leadership, and collaboration—are essential in fields like education, health, and public services [53].

Meanwhile, intrapersonal skills, including self-management, resilience, and adaptability to change, exert a significant influence in the primary and industrial sectors, where autonomy and continuous adaptation are indispensable [54]. Finally, cognitive and affective skills, encompassing critical thinking, ethical judgment, and empathy, demonstrate a transversal applicability across all sectors and hierarchical levels [55].

This diagnosis sustains that improving the quality of graduate profiles requires curricular transformation oriented towards systematically strengthening these competencies—not as an exclusive condition for upward mobility, but as a necessary component to broaden employability and professional development opportunities. The proposal presented in Table 2 serves as a strategic input for this process. By classifying soft skills according to international evidence and linking them to specific productive sectors and their organisational projection, the study provides a concrete and replicable roadmap.

Table 2.

Classification of soft skills according to area of focus, data source, sectors with greatest adaptability, and potential professional application.

Consequently, this study not only identifies a critical need but also offers a structured proposal aligned with the demands of the contemporary labour market [18,28,55,56,57].

Integrating the soft skills matrix into curricular redesign in a sectoral, measurable, and contextualised manner aims to significantly strengthen employability, sustainable professional development, and academic relevance in higher education institutions in Ecuador and across Latin America.

4. Discussion

This study reveals a structural mismatch between university training and the competencies required for graduates’ professional advancement in the Ecuadorian labour market.

Although data indicate a high rate of labour market insertion, more than of graduates remain in operational positions and only about reach tactical or managerial roles. As shown across sectors such as education, health, industry, commerce, and public administration, upward mobility remains limited and cannot be explained solely by the lack of soft skills.

Indeed, competencies such as leadership, effective communication, problem-solving, and adaptability are indispensable for coordination and management roles. However, the evidence from this study does not establish a direct causal link between the absence of these skills and the low presence of graduates in managerial positions. Structural explanations are also plausible: the restricted generation of managerial posts in the Ecuadorian labour market and the prevalence of family-based firms, where leadership roles are often reserved for insiders. Consequently, interpretation of the findings must simultaneously consider both the supply of individual competencies and the structural demand for leadership roles.

The proposal presented in this study seeks to address this challenge through a differentiated curricular tool summarised in Table 2. This sectoral classification of soft skills, based on empirical evidence, identifies which competencies are most relevant for professional progression in each economic sector. Unlike generic or abstract frameworks, this strategy is grounded in occupational realities, enabling more contextualised and effective pedagogical planning. For example, in education and health, the emphasis lies on collaborative leadership and empathetic communication, while in industry and the primary sector, resilience, teamwork, and adaptability to complex environments are more critical.

The proposal gains additional relevance by aligning with international frameworks such as ABET criteria, which mandate the integration of competencies such as communication, ethical judgement, and problem-solving into graduate profiles. This theoretical and practical convergence reinforces the need for curricular redesign that encompasses not only technical knowledge but also socio-emotional dimensions, particularly in disciplines such as engineering where technical training has historically prevailed.

Beyond identifying the gap between universities and the labour market, this study provides a practical and adaptable roadmap for curricular improvement. The progressive integration of soft skills from the earliest stages of training would enhance employability, promote professional mobility, and contribute to more equitable and sustainable labour insertion. Moreover, the applicability of this proposal extends beyond the Salesian Polytechnic University and can be replicated across higher education institutions in Latin America facing similar challenges of academic relevance and professional stagnation.

5. Implications for Education Policy

The findings of this study highlight several implications for higher education policy and quality assurance frameworks.

First, universities must systematically integrate soft skills such as leadership, communication, adaptability, and critical thinking into graduate profiles, ensuring their transversal, measurable, and progressive development. Beyond isolated courses, these competencies should be embedded across the curriculum through active methodologies, continuous assessment, and interdisciplinary projects.

Second, curricular redesign should explicitly reflect the differentiated demands of economic sectors. Aligning academic content and teaching strategies with the realities of the productive environment can improve both graduates’ employability and their organisational mobility.

Third, stronger university–industry linkages are essential. Dual training models, internships, and sectoral agreements can facilitate smoother transitions into strategic roles, reducing the over-concentration of graduates in operational functions.

Fourth, quality assurance agencies—such as CACES in Ecuador—should incorporate soft skills indicators into their accreditation standards. By recognising these competencies as part of quality benchmarks, accreditation systems can create strong incentives for universities to embed them in curricula.

Finally, labour insertion strategies must go beyond entry-level access and actively support career progression. Policies that promote upward professional trajectories are critical to ensure that graduates not only enter the labour market but also achieve sustainable advancement towards leadership and decision-making positions. To achieve this, higher education institutions should incorporate soft skills into graduate profiles, integrating competencies such as leadership, communication, adaptability, and critical thinking in a crosscutting, assessable, and progressive manner.

Likewise, curricula must be redesigned according to economic sectors, adjusting training content and methodologies to the specific demands of the productive environment in order to improve graduates’ employability and organizational mobility. It is also necessary to strengthen university–business ties through dual training, pre-professional internships, and sectoral agreements that facilitate the transition to strategic roles. Furthermore, quality assurance agencies such as CACES should include soft skills indicators in their assessment standards, thereby reinforcing their importance in accreditation processes. Finally, labour market integration strategies should design policies that promote upward trajectories, incorporating mechanisms that foster professional development beyond operational levels.

6. Limitations of the Study

This research proposes a strategy for curricular improvement based on the sectoral integration of soft skills; however, several limitations must be acknowledged.

First, the cross-sectional design does not allow observation of the temporal evolution of professional trajectories, which restricts the analysis of long-term changes in graduates’ career positioning.

Second, although the database covers cohorts between 2013 and 2021, the time elapsed since graduation was not formally included as a variable of analysis. Naturally, recent graduates (for example, from 2021) face lower probabilities of reaching managerial positions compared to graduates from 2013, who already accumulate almost a decade of experience.

The absence of this factor limits the ability to interpret the relationship between soft skills and professional mobility with greater precision.

Third, all participants graduated from a single higher education institution with a humanist orientation (UPS). This may introduce selection bias due to the relative homogeneity of the group and limits the comparability with institutions of different academic profiles. For this reason, the findings should not be automatically generalised to the overall population of Ecuadorian graduates.

Fourth, although the survey collected 3358 responses—a significant volume for statistical analysis—participation was voluntary, which prevents guaranteeing absolute representativeness of the graduate population. In addition, the dataset does not include relevant sociodemographic variables such as gender, age, academic programme, or academic performance. The absence of this information restricts the possibility of conducting more nuanced analyses and prevents identifying potential inequalities in career trajectories.

Fifth, the data are based on self-reported perceptions, which may introduce subjective biases. Moreover, the study did not contrast graduates’ perceptions with the perspectives of employers or other stakeholders, reducing the external validity of the findings. Finally, while the instrument was designed on the basis of the specialised literature, it was not subjected to a formal psychometric validation process.

Consequently, future research should include reliability and validity tests of the instruments, incorporate contextual variables (such as cohort of graduation and programme of study), and develop longitudinal and comparative designs. It is also recommended to integrate the perspective of employers and other key stakeholders in the productive environment, in order to strengthen the robustness and applicability of the findings.

7. Conclusions

This study provides evidence that, in the Ecuadorian context, the development of transversal competencies remains insufficiently incorporated into higher education curricula, even though these skills are decisive for graduates’ employability and long-term career progression. These findings are consistent with recent systematic reviews, which highlight persistent gaps between higher education training and employers’ expectations, emphasizing the urgent need to integrate transversal skills systematically and progressively into graduate profiles [58,59].

The results reveal sectoral differences in the demand for soft skills: interpersonal competencies such as communication, leadership, and collaboration are especially valued in education, health, and public services, while intrapersonal abilities such as resilience, adaptability, and autonomy are essential in the primary and industrial sectors. This sectoral differentiation echoes previous evidence identifying socio-relational, intrapersonal, and cognitive/affective skills as critical dimensions for employability across diverse professional fields [59].

A further contribution of this study lies in bridging the gap between labour market requirements and curriculum design. In this sense, innovative approaches such as Service-Learning have demonstrated their capacity to strengthen the acquisition of transversal competencies, aligning university training with professional demands and fostering the employability of graduates [60].

Finally, beyond the labour market, transversal competencies also contribute positively to academic performance, underscoring their relevance for higher education institutions not only as employability tools but also as drivers of student success [61,62]. Strengthening these competencies, therefore, represents a dual opportunity: to enhance graduates’ integration into the labour market while simultaneously improving their academic trajectories.

Documents Used in the Analysis

- Higher Education Quality Assurance Council (CASES).

- Institutional project on professional skills and employability Applied research carried out by the UPS.

Active stage, which includes interviews and surveys of business owners in the provinces of Azuay, Cañar, Morona Santiago, Guayas, and Pichincha. The information is stored in the archives of the Outreach Department and has been used for comparative and curriculum diagnostic purposes.

Author Contributions

D.P.M.L.: Writing—review and editing, Writing—original draft, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualisation. J.A.C.T.: Writing—review and editing, Writing—original draft, Project administration, Methodology, Funding acquisition. C.L.G.G.: Methodology, Visualisation, Investigation. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The project was carried out under the auspices of research projects, Intervention in the Academic and Business Community to Determine the Perception of the Development of Holistic Competencies in the Educational Process, financed by the Salesian Polytechnic University. RESOLUTION No. 001-005-2023-19-01.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to the use of secondary anonymized data, in accordance with the Organic Law on Personal Data Protection of Ecuador (Art. 7, item 4) and the Universidad Politécnica Salesiana’s Policy on the Processing, Protection, and Use of Personal Data and Information Classification (Resolution No. 128-104-2023-04-19).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable. This study relied on secondary, anonymized data which, in accordance with the Organic Law on Personal Data Protection of Ecuador and the institutional policy of Universidad Politécnica Salesiana, does not require informed consent when used for scientific purposes.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Espina-Romero, L.; Ríos Parra, D.; Noroño-Sánchez, J.G.; Rojas-Cangahuala, G.; Cervera Cajo, L.E.; Velásquez-Tapullima, P.A. Navigating digital transformation: Current trends in digital competencies for open innovation in organizations. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čirjevskis, A. Exploring coupled open innovation for digital servitization in grocery retail: From digital dynamic capabilities perspective. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2022, 15, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPhillips, M.; Nikitina, T.; Tegtmeier, S.; Wójcik, M. What skills for multi-partner open innovation projects? Open innovation competence profile in a cluster ecosystem context. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Galán, J.; Martínez-López, J.Á.; Lázaro-Pérez, C.; García-Cabrero, J.C. Open innovation during web surfing: Topics of interest and rejection by Latin American college students. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2021, 7, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Data science skills and domain knowledge requirements in the manufacturing industry: A gap analysis. J. Manuf. Syst. 2021, 60, 692–706. [CrossRef]

- Cinque, M.; Kippels, S. Soft Skills in Education: The Role of the Curriculum, Teachers, and Assessments; Regional Center for Educational Planning Research Paper; UNESCO: Sharjah, United Arab Emirates, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Cimatti, B. Definition, development, assessment of soft skills and their role for the quality of organizations and enterprises. Int. J. Qual. Res. 2016, 10, 97. [Google Scholar]

- Touloumakos, A.K. Expanded yet restricted: A mini review of the soft skills literature. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Liu, F.; Song, J.S.; Wang, S. Supply chain resilience: A review from the inventory management perspective. Fundam. Res. 2025, 5, 450–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwita, K. The role of soft skills, technical skills and academic performance on graduate employability. SSRN 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyllonen, P.C. Designing tests to measure personal attributes and noncognitive skills. In Handbook of Test Development; Routledge: London, UK, 2015; pp. 190–211. [Google Scholar]

- Poláková, M.; Suleimanová, J.H.; Madzík, P.; Copuš, L.; Molnárová, I.; Polednová, J. Soft skills and their importance in the labour market under the conditions of Industry 5.0. Heliyon 2023, 9, e18670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abelha, M.; Fernandes, S.; Mesquita, D.; Seabra, F.; Ferreira-Oliveira, A.T. Graduate employability and competence development in higher education—A systematic literature review using PRISMA. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkrimpizi, T.; Peristeras, V.; Magnisalis, I. Classification of barriers to digital transformation in higher education institutions: Systematic literature review. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishigame, K. Enhancing learning through continuous improvement: Case studies of the toyota production system in the automotive industry in South Africa. In Workers, Managers, Productivity: Kaizen in Developing Countries; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 197–219. [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov, D.; Dolgui, A.; Sokolov, B. The impact of digital technology and Industry 4.0 on the ripple effect and supply chain risk analytics. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2019, 57, 829–846. [Google Scholar]

- Matu, J.B.; Paik, E.J. Generic skills development in the gulf cooperation council countries and graduate outcomes: A systematic review of the literature. Gulf Educ. Soc. Policy Rev. (GESPR) 2021, 2, 69–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggrawal, S.; Magana, A.J. Teamwork conflict management training and conflict resolution practice via large language models. Future Internet 2024, 16, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passow, H.J. Which ABET competencies do engineering graduates find most important in their work? J. Eng. Educ. 2012, 101, 95–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaputa, V.; Loučanová, E.; Tejerina-Gaite, F.A. Digital transformation in higher education institutions as a driver of social oriented innovations. Soc. Innov. High. Educ. 2022, 61, 81–85. [Google Scholar]

- Melacarne, C.; Orefice, C.; Giampaolo, M. Supporting key competences and soft skills in Higher Education. In Educazione in Età Adulta; Firenze University Press: Firenze, Italy, 2018; p. 181. [Google Scholar]

- Karimi, S.; Ahmadi Malek, F.; Yaghoubi Farani, A.; Liobikienė, G. The role of transformational leadership in developing innovative work behaviors: The mediating role of employees’ psychological capital. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefteri, A.; Menon, M.E. Transformational and transactional school leadership as predictors of teacher self-efficacy. Stud. Educ. Eval. 2025, 86, 101476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacheco-Cubillos, D.B.; Boria-Reverter, J.; Gil-Lafuente, J. Transitioning to agile organizational structures: A contingency theory approach in the financial sector. Systems 2024, 12, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amalu, E.H.; Short, M.; Chong, P.L.; Hughes, D.J.; Adebayo, D.S.; Tchuenbou-Magaia, F.; Lähde, P.; Kukka, M.; Polyzou, O.; Oikonomou, T.I.; et al. Critical skills needs and challenges for STEM/STEAM graduates increased employability and entrepreneurship in the solar energy sector. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 187, 113776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra-Macías, Y.; Tobón, S. Development of transversal skills in higher education programs in conjunction with online learning: Relationship between learning strategies, project-based pedagogical practices, e-learning platforms, and academic performance. Heliyon 2025, 11, e41099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hora, M.T.; Benbow, R.J.; Smolarek, B.B. Re-thinking soft skills and student employability: A new paradigm for undergraduate education. Chang. Mag. High. Learn. 2018, 50, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, P.; Santos, V.; Reis, I.; Martinho, F.; Martinho, D.; Correia Sampaio, M.; José Sousa, M.; Au-Yong-Oliveira, M. Strategic talent management: The impact of employer branding on the affective commitment of employees. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hizi, G. Becoming Role Models: Pedagogies of Soft Skills and Affordances of Person-Making in Contemporary China. Ethos 2021, 49, 135–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirudayaraj, M.; Baker, R.; Baker, F.; Eastman, M. Soft skills for entry-level engineers: What employers want. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ignácio, F.; Ramirez, R.A.; Bergamo, R.O.C. Competências socioemocionais e educação profissional: Práticas docentes em ensino remoto. Rev. Interdiscip. Educ. Territ.—RIET 2021, 2, 246–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.; Fahad, S.; Naushad, M.; Faisal, S. Analysis of livelihood in the world and its impact on world economy. SSRN 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespi, G.; Zuniga, P. Innovation and productivity: Evidence from six Latin American countries. World Dev. 2012, 40, 273–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, Z.; Ye, A.; Mao, J.; Zhang, C. Supplier selection, control mechanisms, and firm innovation: Configuration analysis based on fsQCA. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 139, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmentola, A.; Ferretti, M.; Panetti, E. Exploring the university-industry cooperation in a low innovative region. What differences between low tech and high tech industries? Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2021, 17, 1469–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartram, D. The Great Eight competencies: A criterion-centric approach to validation. J. Appl. Psychol. 2005, 90, 1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, P.; Basuthakur, Y.; Polineni, S.; Paruchuri, S.; Joshi, A. A stakeholder perspective on diversity within organizations. J. Manag. 2025, 51, 383–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dell’Aquila, E.; Marocco, D.; Ponticorvo, M.; Di Ferdinando, A.; Schembri, M.; Miglino, O. Educational Games for Soft-Skills Training in Digital Environments; Advances in Game-Based Learning; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kolster, R. Structural ambidexterity in higher education: Excellence education as a testing ground for educational innovations. Eur. J. High. Educ. 2021, 11, 64–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, J.M.; Davis, F.; Csuti, B.; Noss, R.; Butterfield, B.; Groves, C.; Anderson, H.; Caicco, S.; D’Erchia, F.; Edwards, T.C., Jr.; et al. Gap analysis: A geographic approach to protection of biological diversity. In Wildlife Monographs; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1993; pp. 3–41. [Google Scholar]

- Ritter, B.A.; Small, E.E.; Mortimer, J.W.; Doll, J.L. Designing management curriculum for workplace readiness: Developing students’ soft skills. J. Manag. Educ. 2018, 42, 80–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Beuken, M.; Loos, I.; Maas, E.; Stunt, J.; Kuijper, L. Experiences of soft skills development and assessment by health sciences students and teachers: A qualitative study. BMC Med Educ. 2025, 25, 724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebese, T.; Motubatse, K. How do soft skills enhance the audit committee’s effectiveness in South African municipalities? Int. J. Bus. Ecosyst. Strategy (2687–2293) 2025, 7, 232–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas-Velasco, M. Mapping the (mis) match of university degrees in the graduate labor market. J. Labour Mark. Res. 2021, 55, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, J.; Higson, H. Graduate employability,‘soft skills’ versus ‘hard’business knowledge: A European study. High. Educ. Eur. 2008, 33, 411–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aasheim, C.L.; Li, L.; Williams, S. Knowledge and skill requirements for entry-level information technology workers: A comparison of industry and academia. J. Inf. Syst. Educ. 2009, 20, 349–356. [Google Scholar]

- Crawford, P.; Lang, S.; Fink, W.; Dalton, R.; Fielitz, L. Comparative Analysis of Soft Skills: What is Important for New Graduates? Perceptions of Employers, Alum, Faculty and Students; Association of Public and Land-Grant Unviersities: Washington, DC, USA, 2011; pp. 3–5. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, G.W.; Skinner, L.B.; White, B.J. Essential soft skills for success in the twenty-first century workforce as perceived by business educators. Delta Pi Epsil. J. 2010, 52, 43. [Google Scholar]

- Robles, M.M. Executive perceptions of the top 10 soft skills needed in today’s workplace. Bus. Commun. Q. 2012, 75, 453–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lippman, L.H.; Ryberg, R.; Carney, R.; Moore, K.A. Workforce Connections: Key “Soft Skills” That Foster Youth Workforce Success: Toward a Consensus Across Fields; Child Trends Publication; Child Trends, Inc.: Rockville, MD, USA, 2015; 56p. [Google Scholar]

- Wikle, T.A.; Fagin, T.D. Hard and soft skills in preparing GIS professionals: Comparing perceptions of employers and educators. Trans. GIS 2015, 19, 641–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, D.D.; Chen, Y. STEM education redefined. In Proceedings of the 2017 ASEE Annual Conference & Exposition, Columbus, OH, USA, 25–28 June 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Pócsová, J.; Bednárová, D.; Bogdanovská, G.; Mojžišová, A. Implementation of agile methodologies in an engineering course. Educ. Sci. 2020, 10, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, P.R.d.S.; Jardim, J.; Lopes, M.C.d.S. The soft skills of special education teachers: Evidence from the literature. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, J.; Gomes da Costa, C.; Santos, V. Talent management and generation Z: A systematic literature review through the lens of employer branding. Adm. Sci. 2024, 14, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palhau, M.; Carlos Sá, J.; Ávila, P.; Dinis-Carvalho, J.; Rodrigues, C.; Santos, G. Toyota Way-the Heart of TPS and its Impact on Sustainable Company Growth. Qual. Innov. Prosper. Inovácia Prosper. 2024, 28, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puertas, E.B.; Sotelo, J.M.; Ramos, G. Leadership and strategic management in health systems based on primary health care. Rev. Panam. Salud Publica 2020, 44, e124. [Google Scholar]

- Culcasi, I.; Venegas, R.P.F. Service-Learning and soft skills in higher education: A systematic literature review. Form@re-Open J. Form. Rete 2023, 23, 24–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Álvarez, J.; Vázquez-Rodríguez, A.; Quiroga-Carrillo, A.; Priegue Caamaño, D. Transversal competencies for employability in university graduates: A systematic review from the employers’ perspective. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otermans, P.C.; Nagada, U.; Aditya, D.; Pereira, M. A Systematic Literature Review of Teaching Employability: A Focus on Soft Skills; Curtin University: Perth, Australia, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Villegas, C. A Systematic Review of Research on Soft Skills for Employability. Adv. Educ. 2024, 25, 200–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, S. Soft skills development methods in higher education: A systematic literature review. High. Educ. Ski. Work.-Based Learn. 2025, 15, 868–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).