Transforming the Creative and Social Entrepreneurial Ecosystem: The Broker Roles of Rural Collaborative Workspaces

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Rural Entrepreneurial Ecosystems of Social Enterprises

2.2. CWSs as Brokers in Entrepreneurial Ecosystems

3. Research Design

3.1. Research Methods

3.2. Data Collection and Data Analysis

4. Results

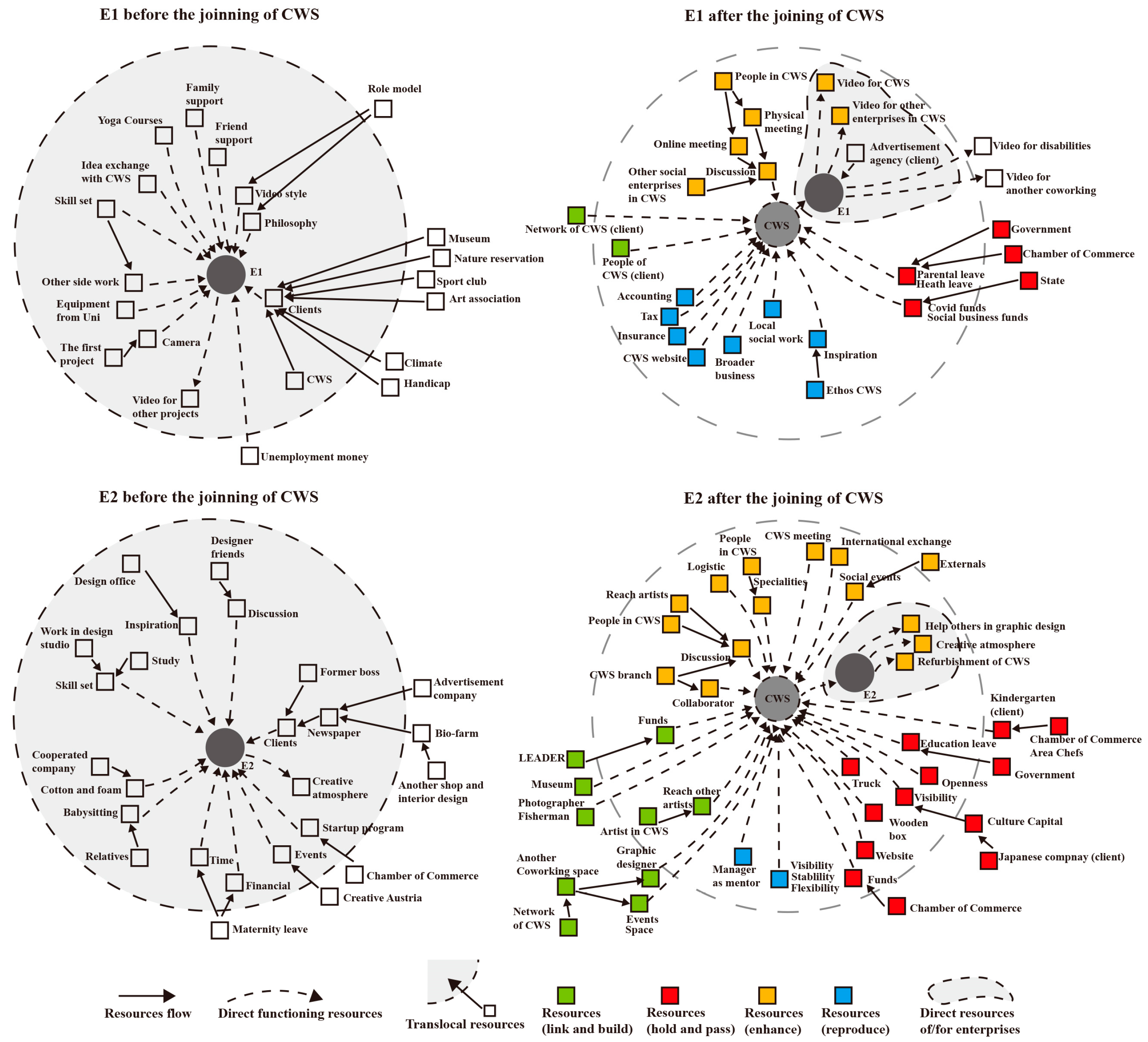

4.1. EE before Joining of the CWS

4.2. EE with CWS

4.2.1. The Power to Link and Build

4.2.2. The Power to Hold and Pass

4.2.3. The Power to Enhance

4.2.4. The Power to Reproduce

4.3. The Broker Roles of the CWS

5. Discussion

5.1. The Transformation of EE

5.1.1. Radical Change of the EE with the Emergence of CWSs

5.1.2. Gradual Change Brought by Social Enterprises

5.2. CWSs as Driving Forces for Transformation

5.3. Integral Impact on the Local Community

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Galloway, L. Can broadband access rescue the rural economy? J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2007, 14, 641–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodge, H.; Carson, D.; Carson, D.; Newman, L.; Garrett, J. Using Internet technologies in rural communities to access services: The views of older people and service providers. J. Rural Stud. 2017, 54, 469–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, A.; Teasdale, S. Unlocking the potential of rural social enterprise. J. Rural Stud. 2019, 70, 144–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defourny, J.; Nyssens, M. Social enterprise in Europe: Recent trends and developments. Soc. Enterp. J. 2008, 4, 202–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosworth, G. Characterising rural businesses—Tales from the paperman. J. Rural Stud. 2012, 28, 499–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saffu, K.; Walker, J. The Country-of-Origin Effect and Consumer Attitudes to “Buy Local” Campaign: The Ghanaian Case. J. Afr. Bus. 2006, 7, 183–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, A.; Evans, R.; Fetzer, E.; Higgings, A.; Lähdesmäki, M.; Linno, K.; Matilainen, A.; Păunescu, C.; Rinne-Koski, K.; Staicu, D.; et al. The Rural Social Enterprise Guidebook of Good Practice: Experience from Estonia, Finland, Germany, Romania and Scotland; University of Helsinki, Ruralia Institute: Helsinki, Finland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Vincze, M.; Birkhölzer, K.; Kaepplinger, S.; Gollan, A.K.; Richter, A. A Map of Social Enterprises and Their Ecosystems in Europe; Country Report for Germany; Europäische Kommission: Brüssel, Belgium, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kreativwirtschaft Austria. Preparations of SME Research Austria for the 7th Austrian Creative Industries Report 2017. 2016. Available online: https://www.kreativwirtschaft.at/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/7KWB-barrierefrei.pdf (accessed on 28 May 2024).

- Parkman, I.D.; Holloway, S.S.; Sebastiao, H. Creative Industries: Aligning Entrepreneurial Orientation and Innovation Capacity. J. Res. Mark. Entrep. 2012, 14, 95–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyubareva, I.; Benghozi, P.J.; Fidele, T. Online Business Models in Creative Industries: Diversity and Structure. Int. Stud. Manag. Organ. 2014, 44, 43–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grantham, A.; Kaplinsky, R. Getting the Measure of the Electronic Games Industry: Development and the Management of Innovation. Int. J. Innov. Manag. 2005, 9, 183–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stam, E.; De Jong, J.P.; Marlet, G. Creative Industries in the Netherlands: Structure, Development, Innovativeness and Effects on Urban Growth. Geogr. Ann. B Hum. 2008, 90, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castañer, X.; Campos, L. Determinants of Artistic Innovation: Bringing in the Role of Organizations. J. Cult. Econ. 2002, 26, 29–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handke, C. Promises and Challenges in Innovation Surveys of the Media Industries. In Management and Innovation in the Media Industry; van Kranenburg, H., Dal Zotto, C., Eds.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2007; pp. 123–152. [Google Scholar]

- Innocenti, N.; Lazzeretti, L. Do the creative industries support growth and innovation in the wider economy? Industry relatedness and employment growth in Italy. Ind. Innov. 2019, 26, 1152–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, P.; Schwartz, D. (Eds.) Creative Regions: Technology, Culture and Knowledge Entrepreneurship; Routledge: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Cooke, P.N.; Lazzeretti, L. (Eds.) Creative Cities, Cultural Clusters and Local Economic Development; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Florida, R. Cities and the Creative Class; Routledge: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Sacco, P.L. Culture as an Engine of Local Development Processes: System-wide Cultural Districts. J. Arts Manag. Law Soc. 2009, 39, 45–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, G. Designing creative places: The role of creative tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 85, 102922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazana, V.; Kazaklis, A. Exploring quality of life concerns in the context of sustainable rural development at the local level: A Greek case study. Reg. Environ. Chang. 2009, 9, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Townsend, L.; Wallace, C.; Fairhurst, G.; Anderson, A. Broadband and the creative industries in rural Scotland. J. Rural Stud. 2017, 54, 451–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barraket, J.; Eversole, R.; Luke, B.; Barth, S. Resourcefulness of locally-oriented social enterprises: Implications for rural community development. J. Rural Stud. 2019, 70, 188–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prado, A.M.; Robinson, J.A.; Shapira, Z. Serving rural low-income markets through a social entrepreneurship approach: Venture creation and growth. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2022, 16, 826–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouncken, R.B.; Laudien, S.M.; Fredrich, V.; Görmar, L. Coopetition in coworking-spaces: Value creation and appropriation tensions in an entrepreneurial space. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2018, 12, 385–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surman, T. Building Social Entrepreneurship through the Power of Coworking. Innov. Technol. Gov. Glob. 2013, 8, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowell, M.; Lyon-Hill, S.; Tate, S. It takes all kinds: Understanding diverse entrepreneurial ecosystems. J. Enterprising Communities People Places Glob. Econ. 2018, 12, 178–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauger, F.; Pfnür, A.; Strych, J.-O. Coworking spaces and Start-ups: Empirical evidence from a product market competition and life cycle perspective. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 132, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loots, E.; Neiva, M.; Carvalho, L.; Lavanga, M. The entrepreneurial ecosystem of cultural and creative industries in Porto: A sub-ecosystem approach. Growth Chang. 2021, 52, 641–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinuzzi, C. Working alone together: Coworking as Emergent Collaborative Activity. J. Bus. Tech. Commun. 2012, 26, 399–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waters-Lynch, J.; Potts, J.; Butcher, T.; Dodson, J.; Hurley, J. Coworking: A Transdisciplinary Overview. Available at SSRN 2712217. 2016. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2712217 (accessed on 30 April 2024).

- Boari, C.; Riboldazzi, F. How knowledge brokers emerge and evolve: The role of actors’ behaviour. Res. Policy 2014, 43, 683–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, R.M.; Gould, R.V. A Dilemma of State Power: Brokerage and Influence in the National Health Policy Domain. Am. J. Sociol. 1994, 99, 1455–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruns, K.; Bosma, N.; Sanders, M.; Schramm, M. Searching for the existence of entrepreneurial ecosystems: A regional cross-section growth regression approach. Small Bus. Econ. 2017, 49, 31–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, B. Sustainable valley entrepreneurial ecosystems. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2006, 15, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, C.; Brown, R. Entrepreneurial ecosystems and growth oriented entrepreneurship. Final Rep. OECD Paris 2014, 30, 77–102. [Google Scholar]

- Spigel, B. The Relational Organization of Entrepreneurial Ecosystems. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2017, 41, 49–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuebart, A.; Ibert, O. Beyond territorial conceptions of entrepreneurial ecosystems: The dynamic spatiality of knowledge brokering in seed accelerators. Z. Wirtschgeogr. 2019, 63, 118–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nel, E.; Stevenson, T. The catalysts of small town economic development in a free market economy: A case study of New Zealand. Local Econ. 2014, 29, 486–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombelli, A.; Krafft, J.; Vivarelli, M. To be born is not enough: The key role of innovative start-ups. Small Bus. Econ. 2016, 47, 277–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isenberg, D.J. The entrepreneurship ecosystem strategy as a new paradigm for economic policy: Principles for cultivating entrepreneurship. In Proceedings of the Institute of International and European Affairs, Dublin, Ireland, 12 May 2011; Volume 1, pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Doherty, B.; Haugh, H.; Lyon, F. Social enterprises as hybrid organizations: A review and research agenda. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2014, 16, 417–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huggins, R. The success and failure of policy-implanted inter-firm network initiatives: Motivations, processes and structure. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2000, 12, 111–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, C. A framework for the governance of social enterprise. Int. J. Soc. Econ. 2006, 33, 376–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roundy, P.T. Social entrepreneurship and entrepreneurial ecosystems: Complementary or disjoint phenomena? Int. J. Soc. Econ. 2017, 44, 1252–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peredo, A.M.; McLean, M. Social entrepreneurship: A critical review of the concept. J. World Bus. 2006, 41, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Bruin, A.; Roy, M.J.; Grant, S.; Lewis, K.V. Advancing a Contextualized, Community-Centric Understanding of Social Entrepreneurial Ecosystems. Bus. Soc. 2023, 62, 1069–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roundy, P.T.; Lyons, T.S. Where are the entrepreneurs? A call to theorize the micro-foundations and strategic organization of entrepreneurial ecosystems. Strateg. Organ. 2023, 21, 447–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borzaga, C.; Galera, G.; Franchini, B.; Chiomento, S.; Nogales, R.; Carini, C. Social Enterprises and Their Ecosystems in Europe; Comparative Synthesis Report; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2020; Available online: https://www.bollettinoadapt.it/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/KE0220042ENN.en_.pdf (accessed on 30 April 2024).

- Roundy, P.T.; Lyons, T.S. Humility in social entrepreneurs and its implications for social impact entrepreneurial ecosystems. J. Bus. Ventur. Insights 2022, 17, e00296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, T.A.; Purdy, J.M.; Ventresca, M.J. How entrepreneurial ecosystems take form: Evidence from social impact initiatives in Seattle. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2018, 12, 96–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cukier, D.; Kon, F.; Lyons, T.S. Software Startup Ecosystems Evolution: The New York City Case Study. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Conference on Engineering, Technology and Innovation/IEEE International Technology Management Conference (ICE/ITMC), Trondheim, Norway, 13–15 June 2016; Volume 2016, pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrington, K. Is your entrepreneurial ecosystem scaling? An approach to inventorying and measuring a region’s innovation momentum. Innov. Technol. Gov. Glob. 2016, 11, 126–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, S. In the making: Open Creative Labs as an emerging topic in economic geography? Geogr. Comp. 2019, 13, e12463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, B.; Bürkner, H.-J. Open workshops as sites of innovative socio-economic practices: Approaching urban post-growth by assemblage theory. Local Environ. 2018, 23, 680–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boschma, R. Role of proximity in interaction and performance: Conceptual and empirical challenges. Reg. Stud. 2005, 39, 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, P.; Steyaert, C. The politics of narrating social entrepreneurship. J. Enterprising Communities People Places Glob. Econ. 2010, 4, 85–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, A.W.; Dacin, P.A.; Dacin, M.T. Collective Social Entrepreneurship: Collaboratively Shaping Social Good. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 111, 375–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roundy, P.T.; Bonnal, M. The Singularity of Social Entrepreneurship: Untangling its Uniqueness and Market Function. J. Entrep. 2017, 26, 137–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquis, C.; Lounsbury, M.; Greenwood, R. Introduction: Community as an Institutional Order and a Type of Organizing. In Communities and Organizations; Marquis, C., Lounsbury, M., Greenwood, R., Eds.; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2011; Volume 33, pp. ix–xxvii. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornton, P.H.; Ocasio, W.; Lounsbury, M. The Institutional Logics Perspective: A New Approach to Culture, Structure and Process; OUP: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Avdikos, V.; Pettas, D. The new topologies of collaborative workspace assemblages between the market and the commons. Geoforum 2021, 121, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, R.; Mason, C. Looking inside the spiky bits: A critical review and conceptualisation of entrepreneurial ecosystems. Small Bus. Econ. 2017, 49, 11–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purbasari, R.; Wijaya, C.; Rahayu, N. Most Roles Actors Play in Entrepreneurial Ecosystem: A Network Theory Perspective. J. Entrep. Educ. 2020, 23, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Lange, B.; Schmidt, S. Entrepreneurial ecosystems as a bridging concept? A conceptual contribution to the debate on entrepreneurship and regional development. Growth Change 2021, 52, 790–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bednář, P.; Danko, L.; Smékalová, L. Coworking spaces and creative communities: Making resilient coworking spaces through knowledge sharing and collective learning. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2023, 31, 490–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, P.; Ressia, S. Neither office nor home: Coworking as an emerging workplace choice. Employ. Relat. Rec. 2015, 15, 42–57. [Google Scholar]

- Gandini, A.; Cossu, A. The third wave of coworking: ‘Neo-corporate’ model versus ‘resilient’ practice. Eur. J. Cult. Stud. 2019, 14, 430–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, S.; Brinks, V.; Brinkhoff, S. Innovation and creativity labs in Berlin. Z. Wirtschgeogr. 2014, 58, 232–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuebart, A. Open creative labs as functional infrastructure for entrepreneurial ecosystems: Using sequence analysis to explore tempo-spatial trajectories of startups in Berlin. Res. Policy 2022, 51, 104444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orel, M.; Mayerhoffer, M.; Fratricova, J.; Pilkova, A.; Starnawska, M.; Horvath, D. Coworking spaces as talent hubs: The imperative for community building in the changing context of new work. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2022, 16, 1503–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cnossen, B.; Bencherki, N. The role of space in the emergence and endurance of organizing: How independent workers and material assemblages constitute organizations. Hum. Relat. 2019, 72, 1057–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Prentice, C.; Wallis, J.; Patel, A.; Waxin, M.-F. An integrative study of the implications of the rise of coworking spaces in smart cities. Entrep. Sustain. Issues 2020, 8, 467–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vlasov, M.; Bonnedahl, K.J.; Vincze, Z. Entrepreneurship for resilience: Embeddedness in place and in trans-local grassroots networks. J. Enterprising Communities People Places Glob. Econ. 2018, 12, 374–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motoyama, Y.; Knowlton, K. Examining the connections within the startup ecosystem: A case study of St. Louis. Entrep. Res. J. 2017, 7, 20160011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avdikos, V.; Iliopoulou, E. Community-Led Coworking Spaces: From Co-location to Collaboration and Collectivization. In Creative Hubs in Question: Place, Space and Work in the Creative Economy; Gill, R., Pratt, A.C., Virani, T.E., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 111–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bednář, P.; Danko, L. Coworking Spaces as a Driver of the Post-Fordist City: A Tool for Building a Creative Ecosystem. Eur. Spat. Res. Policy 2020, 27, 105–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barley, S.R. Technicians in the workplace: Ethnographic evidence for bringing workinto organizational studies. Adm. Sci. Q. 1996, 41, 404–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, L.; Mingo, S.; Chen, D. Collaborative brokerage, generative creativity, and creative success. Adm. Sci. Q. 2007, 52, 443–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burt, R.S.; Soda, G. Network Capabilities: Brokerage as a Bridge Between Network Theory and the Resource-Based View of the Firm. J. Manag. 2021, 47, 1698–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burt, R.S. The Network Structure of Social Capital. Res. Organ. Behav. 2000, 22, 345–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burt, R.S. Structural Holes and Good Ideas. Am. J. Sociol. 2004, 110, 349–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Z.; Tsui, A.S. When brokers may not work: The cultural contingency of social capital in Chinese high-tech firms. Adm. Sci. Q. 2007, 52, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obstfeld, D. Social Networks, the Tertius Iungens Orientation, and Involvement in Innovation. Adm. Sci. Q. 2005, 50, 100–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, T.; Nelson, R.E. Creating Something from Nothing: Resource Construction through Entrepreneurial Bricolage. Adm. Sci. Q. 2005, 50, 329–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burt, R.S. Structural Holes: The Social Structure of Competition; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, S.-W.; Rondi, E.; Levin, D.Z.; De Massis, A.; Brass, D.J. Network Brokerage: An Integrative Review and Future Research Agenda. J. Manag. 2020, 46, 1092–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burt, R.S. Brokerage and Closure: An Introduction to Social Capital; OUP: Oxford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes, A.J.; Ferreira, J.J. Entrepreneurial ecosystems and networks: A literature review and research agenda. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2022, 16, 189–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombelli, A.; Paolucci, E.; Ughetto, E. Hierarchical and relational governance and the life cycle of entrepreneurial ecosystems. Small Bus. Econ. 2019, 52, 505–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Azungah, T. Qualitative research: Deductive and inductive approaches to data analysis. Qual. Res. J. 2018, 18, 383–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mik-Meyer, N. Multimethod qualitative research. In Qualitative Research; Silverman, D., Ed.; SAGE: London, UK, 2020; pp. 357–374. [Google Scholar]

- Ibert, O.; Müller, F.C. Network dynamics in constellations of cultural differences: Relational distance in innovation processes in legal services and biotechnology. Res. Policy 2015, 44, 181–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreier, M. Qualitative content analysis in practice. In Qualitative Content Analysis in Practice; Schreier, M., Ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2012; pp. 1–280. [Google Scholar]

- DeLanda, M. Deleuzian social ontology and assemblage theory. In Deleuze and the Social; Fuglsang, M., Ed.; Edinburgh University Press: Edinburgh, UK, 2006; pp. 250–266. [Google Scholar]

- DeLanda, M. A New Philosophy of Society: Assemblage Theory and Social Complexity; Bloomsbury Publishing: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Karaman, O. Book Review, Manuel DeLanda, A New Philosophy of Society: Assemblage Theory and Social Complexity. Antipode 2008, 40, 935–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Enterprise 1 (E1) | Enterprise 2 (E2) | CWS (C) | Additional Interviews |

|---|---|---|---|

| Video-making cooperative; Two people; Members of CWS cooperative; Not fixed in CWS; Join the CWS | Product design; One-person company; Management role in the CWS cooperative; A fixed desk in CWS | A cooperative (owned, managed, and run by and for their members to realize their common goals); Bottom-up, flexible membership; Located in a school; Has branches; Social ethos | Collaborators; Supporters |

| 1.5 h interview | 2 h interview | 1 plus 1.5 h interview | 9 interviews of 1 h each |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gao, C.; Psenner, E. Transforming the Creative and Social Entrepreneurial Ecosystem: The Broker Roles of Rural Collaborative Workspaces. Societies 2024, 14, 81. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc14060081

Gao C, Psenner E. Transforming the Creative and Social Entrepreneurial Ecosystem: The Broker Roles of Rural Collaborative Workspaces. Societies. 2024; 14(6):81. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc14060081

Chicago/Turabian StyleGao, Chen, and Eleonora Psenner. 2024. "Transforming the Creative and Social Entrepreneurial Ecosystem: The Broker Roles of Rural Collaborative Workspaces" Societies 14, no. 6: 81. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc14060081

APA StyleGao, C., & Psenner, E. (2024). Transforming the Creative and Social Entrepreneurial Ecosystem: The Broker Roles of Rural Collaborative Workspaces. Societies, 14(6), 81. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc14060081