Abstract

Geography is a significant element of social innovation. This paper focuses on exploring differences and similarities in the characteristics and contributions towards impact of Work Integration Social Enterprises (WISEs), a form of social innovation which provides otherwise unmet services and opportunities to people at risk of social and economic exclusion and distant from the labour market, in rural and urban areas of Ireland. To do so, we use data from 336 surveys from urban (213) and rural (123) WISEs and conduct an exploratory and spatially sensitive analysis to compare the characteristics, in terms of organisational age, legal and governance form, multiplicity of activities, revenue diversification; and contributions towards impact, in terms of geographical focus/reach, employment, volunteers, and income generation. Our analysis shows that WISEs in urban and rural areas present rather similar organisational characteristics and ways of functioning (legal structure, multiactivity, multiple sources of funding), but their contributions to socioeconomic impact differ according to their spatial location, with urban WISEs generating significantly more employment and income than their rural counterparts. Our study illustrates that socially innovative organisations are spatially sensitive, and that context influences their capacity to create sustainable employment opportunities and contribute to the local economy.

1. Introduction

Significant differences persist in terms of employment for disadvantaged groups in Ireland; for example, persons with disabilities presented an unemployment rate of 26.6% compared to 11.5% of people who do not have a disability []. In spite of this, progress has been made in the last decades towards the work integration of disadvantaged groups, such as persons with disabilities and the long-term unemployed, through policies related to Activation Labour Market Programmes (ALMPs) and the development of new organisational forms such as Work Integration Social Enterprises (WISEs) [].

These constitute social innovations, defined in broad terms as novel ways of achieving certain goals related to the satisfaction of human needs [], such as the provision of unmet services []. Social innovative practices are characterised by collaborative relations among different actors/players [] and the empowerment of disadvantaged groups []. These innovations do not occur in a vacuum, but they are influenced by the contexts in which they are developed and implemented. However, this influence is not unidirectional as social innovations use/harness elements from their contexts to develop their practices/solutions, but they can also impact and, on certain occasions, transform the contexts in which they are embedded [,]. A significant element of the context for social innovations is the geographical space where they are based and operate []. Despite some research has been conducted on social innovations in rural and urban spaces, fewer studies have focused on comparing the characteristics and impact of social innovations based in rural and urban settings [].

Our study focuses on a specific form of social innovation, namely WISEs operating in Ireland. WISEs can be viewed as a social innovation providing training and employment opportunities to those at risk of social and economic exclusion, most notably those distant from the labour market []. Despite the fact that WISEs are not a new phenomenon in Europe and some have been pressured towards institutional isomorphism [], with the consequence of reducing their initial novelty, WISEs have evolved over the last decades, addressing the needs of new groups distant from the labour market, e.g., refugees, and responding to challenges which have been getting increasing attention, such as the depopulation of rural areas, climate change, and the digital divide []. WISEs represent ‘relative’ social innovations that provide otherwise unmet services and opportunities to people at risk of social and economic exclusion and distant from the labour market [].

There is scarce research that takes a spatial approach to the study of WISEs (see [] for example). Contributing to filling this gap, our study is guided by the following research question: What are the similarities and differences in the characteristics and contribution towards impact of WISEs operating in rural and urban areas of Ireland? To answer this question, we have used data from 336 surveys from urban (213) and rural (123) WISEs declaring to avail of statutory active labour market programmes, specifically targeting people distant from the labour market. We conducted an exploratory and spatially sensitive analysis [] to compare the characteristics of rural–urban WISEs in terms of their organisational age, legal and governance form, multiactivity and revenue diversification; and their contribution towards impact in terms of geographical focus/reach, employment, volunteers, and income.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows: Section 2 presents a spatial perspective of WISEs, introducing the main concepts of this study and the state of research. Section 3 describes the methodology followed in this study. Section 4 outlines the results from our exploratory and spatially sensitive analysis of rural–urban Irish WISEs. Finally, Section 5 discusses our results with those of the previous literature on social innovation, social enterprises and WISEs, and develops some conclusions, further research recommendations, and limitations of the study.

2. A Spatial Perspective of WISEs: Concepts and State of Research

Forming part of the wider social economy, WISEs are organisations whose main aim is to “integrate those with intellectual or physical disabilities and other disadvantaged groups, including the long-term unemployed, back into the labour market and society through a productive activity” [] (p. 416). WISEs are not a new phenomenon; prototypes of these organisations were established back in the 19th century with the development of the first social economy organisations []. However, WISEs significantly developed in line with labour integration policies launched in the second half of the 20th century in Europe []. Within Ireland, WISEs entered significantly within the policy discourse in the 1990s and later in the first part of the 21st century with policies such as the Social Economy Programme, later renamed as Community Services Programme, and other ALMPs such as Tús, Community Employment Scheme, and Rural Social Scheme []. Despite their long trajectory, recent research has shown how WISEs have developed new services, for example, in the sectors of renewable energy and the circular economy [,], and have expanded their target to other groups such as refugees []. Another characteristic of WISEs in Europe and Ireland is that they tend to develop concurrently more than one activity [] and operate within a wide range of sectors, providing services such as catering, gardening, recycling, circular economy, childcare, eldercare, among others []. This provision of services is complementary to the satisfaction of human needs related to social and economic integration by offering employment opportunities [], therefore increasing individuals’ income levels to enhance their living standards [], and expanding avenues for social connections []. In this light, WISEs are conceptualised as a form of social innovation [].

As part of the social economy, WISEs are also characterised by their democratic governance structures where decision-making tends to follow the principle of one person–one vote rather than being based on the capital of shareholders. This is usually reflected in WISEs’ legal and governance forms, which, despite being particular to each country, usually follow these democratic principles []. In addition, WISEs tend to blur the boundaries between the public sector, for-profit sector, and the third sector, resulting in hybrid organisations [,]. As hybrid organisations, WISEs tend to combine different resources both monetary (market and non-market) and non-monetary [] to develop their activities and sustain the organisation. This resource mix is often reflected in their revenue diversification.

Besides the abovementioned characteristics of WISEs, through their activities and specific way of functioning in the provision of employment for people of disadvantaged groups, these organisations aim to generate impact by contributing to more socio-economically inclusive development in the territories where they operate []. The concept of impact is contested and refers to long-term changes from an initial situation in the conditions of a person, social group, community and/or territory []. There is an increasing call for social impact assessment in WISEs and, more generally, in social enterprises and social innovations []. However, the need for long-term, comparable and counterfactual evidence for assessing the impact of WISEs poses significant challenges1 [,]. Despite the challenge of attribution between outputs and impact, outputs such as job creation generated by WISEs aim to contribute to the well-being of individuals from disadvantaged groups and within these, especially of women [], by having a substantial impact on improving their quality of life, empowering them on a personal level, fostering better social integration, and preventing exclusion []. The focus of WISEs on active engagement of distant labour people, co-creation, and co-production induces learning among those participating in the WISE, including beneficiaries, staff, and volunteers []. The participation of volunteers within WISEs can present some downsides due to excessive reliance, which can lead to burnout and challenges related to the sustainability of the organisation []. Nevertheless, the participation of volunteers in these organisations has also been acknowledged as an important factor contributing to the development of social relations, social capital, and sense of community [,]. In addition, WISEs develop productive activities acting within a market-oriented logic; this generates economic outputs in the form of income which is later reinvested to a large extent into the organisation and/or its activities []. This income generation, consequently, contributes to the improvement of the enterprise itself and can also contribute to the economic development of local communities [].

Despite the abovementioned general characteristics and the potential contributions of WISEs in terms of impact, research has pointed out how these organisations and some of their characteristics are contingent on geographic and institutional factors, such as the welfare regimes in which WISEs have developed []. In this regard, Defourny and Nyssens [] illustrated that WISEs in liberal welfare states are increasingly becoming more business-oriented, even transforming themselves by adopting more commercial forms and redefining themselves as social businesses focused on the most marginalised and long-term disadvantaged workers [], while, for example, in corporatist welfare states, WISEs derive a variety of market and non-market resources from multiple sources including the state, private, philanthropic, and community sectors [].

To accomplish the social mission of targeting underserved or disadvantaged populations, social enterprises in general, and WISEs in particular, are affected by spatial parameters pertaining to the urban–rural divides []. These organisations tend to remain embedded within their local community [] and rely on engaging the local community as an essential means to harness resources and establish credibility in their respective areas []; however, previous research has pointed towards some differences in social enterprises operating in urban and rural areas [,].

Within urban settings, researchers have focused on institutional assemblages, exploring how social economy organisations operate within urban economies and can serve as an alternative model for local economic development more sensitive to the inclusion of vulnerable groups, in line with WISEs. This exploration extends to understanding practices that resonate with shifts in governance cultures []. The transformative potential of social economy organisations in urban contexts is underscored by the recent emergence of radical municipalism, a phenomenon exemplified by urban social movements [,]. These movements are actively ‘occupying institutions’ to advocate for municipal socialist policies that challenge neoliberal austerity and significantly champion grassroots social innovation and the social economy []. These phenomena are often explored through a social capital lens, offering a nuanced view of the transformative potential embedded in social innovation [,]. However, more critical views highlight that urban WISEs often act as compensatory mechanisms for market inadequacies and should be approached with scepticism [].

In rural areas, social enterprises are especially noteworthy because they typically demonstrate a profound attachment to their particular locations [,]. Likewise, rural social enterprises develop their social innovative capacity through ‘placial embeddedness’, which refers to their deep understanding and utilisation of the local resources, as well as their genuine commitment to the well-being of these places []. Accordingly, the rural environment significantly shapes the nature of their activities and their operational methods []. In this context, rural social enterprises have been identified as organisations that contribute to local development through social innovation [,]. On the other hand, previous research has shown challenges for rural social enterprises, with distinctive geographical (remoteness) creating substantial cost and risk for scaling in rural contexts [].

Although the literature on social innovation and social enterprise highlights the importance of reconnection at different spatial scales [], few studies have compared and/or interlinked rural and urban geographies [] and there is scarce research that takes a spatial approach to understanding WISEs []. Responding to this gap, our research studies the similarities and differences in the organisational characteristics and contribution towards impact of WISEs operating in rural and urban areas of Ireland.

3. Materials and Methods

To explore similarities and differences in the characteristics and contributions towards impact of social innovative organisations, such as WISEs operating in rural and urban areas of Ireland, this paper uses data from a national survey of social enterprises conducted in Ireland in 2022. The survey contained 18 close-ended (single and multiple-choice) questions. The questions address a variety of themes relevant to social enterprises, including spatial location; sector(s) of activity; longevity/year of foundation; legal form; market reach (local–international); levels and nature of staffing (full/part-time, gender, age groups, participation in Activation Labour Market Programmes); levels and nature of volunteers and board members (gender, age groups); and income (annual and sources of income)2.

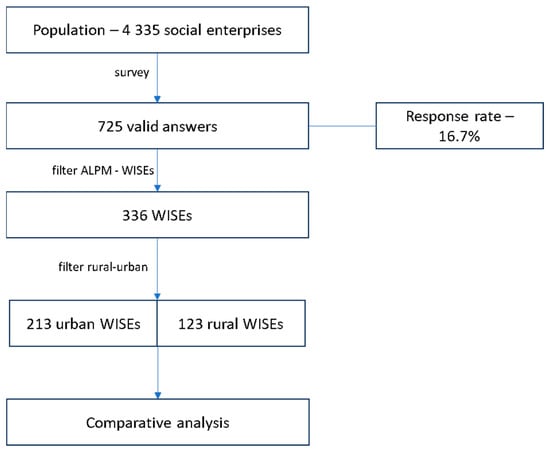

The survey was distributed online between September and October 2022 to a total of 4335 social enterprises; 725 valid answers were obtained after deleting duplicates and those with invalid answers, representing a response rate of 16.7%. For this article studying rural/urban WISEs, we did not use all the answers, but we selected those cases in which social enterprises reported participating in Activation Labour Market Programmes as we intended to analyse social innovative organisations which are targeting the work integration of people distant from the labour market such as long term unemployed and/or people with disabilities. This filter was applied to the 725 valid answers from the national survey, obtaining 336 valid answers for our study. Furthermore, we classified these answers according to their rural/urban location following the official definition of the Central Statistics Office of Ireland (CSO), which defines “an urban area as a town with a total population of 1500 or more and therefore towns with a population of less than 1500 are included in rural areas” []. A total of 213 valid answers for WISEs operating in urban areas and 123 in rural areas were obtained (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Method’s process.

In terms of analysis, we first conducted an exploratory spatially sensitive analysis [] through descriptive statistics to compare rural–urban WISEs in Ireland. We specifically focused on organisational features, including year of establishment, multiactivity, legal and governance form and sources of income; and on their contributions towards impact in terms of geographical reach of their activities, employment creation, volunteering and income generation (Table 1).

Table 1.

Variables and description.

Complementary, we conducted a bivariate analysis to test the statistical significance of the relationship between the rural–urban location of the WISEs and the variables included within the descriptive analysis. Due to the non-normal distribution of our sample (determined by Shapiro–Wilk tests3, see Appendix A), we used the non-parametrical tests4 Mann–Whitney test (U) to evaluate significant relationships in continuous variables (e.g., volunteers’ level) and Chi-Square tests (X2) when dealing with categorical data (e.g., legal form, sources of income) []. The p values (p) of each test were used to determine statistical significance (p < 0.05). All statistical analyses were produced using Jamovi (version 2.4.8.) and R (version 4.2.3).

4. Findings

The following section presents the similarities and differences between urban and rural Irish WISEs regarding their organisational features (i.e., year of establishment, multiactivity, legal and governance form, and sources of income) and their contributions towards impact in terms of geographical reach/focus of their activities, employment, volunteering, and income generation.

4.1. Organisational Features in Rural and Urban WISEs

4.1.1. Longevity

Descriptive statistics show that the median longevity in both rural and urban Irish WISEs is over 20 years (Table 2); with non-parametric test showing no statistical significance difference (U = 12,198, p = 0.29), between rural and urban WISEs. WISEs’ long-term operations indicate their ability to adapt to changing social, economic, and regulatory contexts and thus their resilience within the Irish landscape.

Table 2.

WISEs’ year of establishment.

4.1.2. Multiactivity

WISEs are characterised by their multiactivity nature as besides their primary or core activity, they often develop some further services/activities. Typically, Irish WISEs in rural and urban areas conduct three types of activities concurrently (Table 3). Our non-parametric test (Mann–Whitney) found no significant difference in the reported number of activities between rural and urban WISEs (U = 12,946, p = 0.86). The multiactivity approach of both urban and rural WISEs highlights their potential to address a wide spectrum of needs and thus maintaining relevance over time.

Table 3.

WISEs’ activities.

4.1.3. Legal Form

The Company Limited by Guarantee (CLG) represents the main legal form of WISEs in Ireland, 90.2% in rural areas and 87.8% in urban areas (see Table 4). The Chi-Square test shows that this difference between rural and urban WISEs is not statistically significant (X2 = 0.008, p = 0.93). The CLG represents a legal form in which members of the company/organisation have limited liability. CLGs are governed by a board of voluntary directors with decision-making usually based on the rule of one person–one vote. This legal form is also used by many charitable organisations in Ireland. Our findings also show that other forms, such as Company Limited by Shares (CLS) and Cooperative5, are used by WISEs in Ireland to a much lesser extent both in rural and urban settings.

Table 4.

WISEs’ legal form.

4.1.4. Sources of Income: Diversification and Type

WISEs in Ireland use different sources of income to fund their activities, including the sale of goods and/or services, grants, service contracts, philanthropy, fundraising, and membership fees. WISEs operating in urban and rural areas typically use three different sources of income to fund their activities and the organisation (see Table 5). Our analysis shows that less than 6% of WISEs in urban and rural areas use only one source of income and thus adopt a single funding strategy. About two-thirds of WISEs (69.9% in the case of urban WISEs and 64.4% in their rural counterparts) mix between two and three sources of income thus having a diversified strategy; and about one-quarter of rural WISEs and 30% of urban WISEs use more than three funding strategies, thus have a highly diversified funding strategy. Despite our descriptive analysis shows some differences between rural and urban WISEs, these are not statistically significant as shown by Chi-Square tests conducted (see Table 6). Diversification of income sources suggests a resourceful approach in both urban and rural WISEs in mixing different types of resources and mitigating risks associated with changes in funding availability and/or economic conditions.

Table 5.

WISEs’ sources of income: number.

Table 6.

WISEs’ sources of income: diversification.

Within the different types of sources of income, grants and sales of goods and services are the two sources of income used by the great majority of Irish WISEs in both rural and urban areas. Fundraising is used by approximately half of rural WISEs but only by 38% of WISEs operating in urban areas. Conversely, contract services with the government through open tenders and service arrangements (non-open tender), philanthropy, and membership fees are more widely used by urban WISEs than their rural counterparts (see Table 7).

Table 7.

WISEs’ sources of income: types.

Despite some differences between rural and urban WISEs shown by the descriptive statistics, the Chi-Square tests performed only show a statistically significant relationship between the (rural–urban) location of WISEs and three sources of income categories, namely contracts with the government for service arrangements (X2 = 6.90, p = 0.009) and philanthropy (X2 = 6.91, p = 0.009), with urban WISEs using these sources to a greater extent, and, fundraising (X2 = 4.3, p = 0.04), with rural WISEs using this source of income to a greater extent. These differences indicate a greater access of urban WISEs to some public resources, such as those related to government contracts in the form of service arrangements (non-open tender contracts) and also to resources related to philanthropists and CSR; whereas rural WISEs develop (community) fundraising to finance their activities to a greater extent than their urban counterparts.

Despite some differences, our findings show rather similar organisational features between rural and urban Irish WISEs regarding their longevity, multiactivity nature, legal and governance form, and (most) sources of income.

4.2. Contributions towards Impact in Rural–Urban WISEs

4.2.1. Focus and Reach of Activities

Rural and urban Irish WISEs show similar trends in terms of the focus and reach of their activities, over 80% focus on the immediate localities in which they operate—this is almost 90% in the case of WISEs in rural settings; almost half expand their operations within their counties, less than a quarter operate nationally, and less do internationally (see Table 8). The Chi-square tests conducted show only a significant association between WISEs’ geographical location (rural/urban) and the local reach/focus of their activities (X2 = 4.4, p = 0.04), whereas for the rest of levels, this relationship is not statistically significant (see Table 8).

Table 8.

WISEs’ focus and reach of their activities.

4.2.2. Employment

Our descriptive analysis shows how the majority of WISEs in rural areas (57.7%) are microenterprises employing less than 10 people (Table 9). In the case of urban WISEs, approximately half of these organisations (48.6%) are small enterprises contributing to the employment of between 10 and 49 people. Importantly, also in terms of employment, about 10% of WISEs in urban areas are medium enterprises and thus employ between 50 and 249 staff, this being the case for only 1.6% of rural WISEs. Our Chi-Square tests reveal a statistically significant relationship between the size and location of WISEs for microenterprises, which are predominantly situated in rural areas (X2 = 10.5, p = 0.001) and for medium enterprises, which have a significantly stronger presence in urban areas (X2 = 9.5, p = 0.002). These differences in employment reflect the relevance of the context for the contribution towards impact of WISEs as, in general terms, Irish rural areas present low-density population and weaker economic and labour markets than urban settings.

Table 9.

WISEs’ employment size.

In terms of gender composition of the workforce, women represent approximately two-thirds of the staff in WISEs; thus, these organisations present a greater contribution towards women’s employment both in urban and rural areas. Despite our descriptive analysis shows a slightly higher proportion of women as employees in urban (66.1%) than rural (63.2%) WISEs (Table 10), the non-parametric test conducted shows that this difference is not statistically significant (U = 12,281, p = 0.37).

Table 10.

WISEs’ workforce according to gender distribution.

In terms of age distribution, our analysis shows that employees over 50 years old are more prominent in WISEs based and operating in rural areas, where this cohort represents 40.8% of the employees compared to 33.7% in urban WISEs (Table 11). This difference reflects the older demographic profile of rural areas.

Table 11.

WISEs’ workforce according to age distribution.

4.2.3. Volunteers

Regular volunteers and voluntary board members are key to the functioning of WISEs in Ireland. The median of volunteers contributing to WISEs operations is 12 for the case of rural WISEs and 12 for those placed in urban areas, therefore differences are minimal, the non-parametric test (Mann–Whitney) indicates no statistically significant relationship between the rural–urban location of WISEs and volunteer levels (U = 12,797, p = 0.7). Regarding gender distribution among volunteers (including voluntary board members), our descriptive analysis shows a slightly higher number of males in the case of those WISEs based in urban areas, and females are slightly predominant in rural WISEs (Table 12). However, the non-parametric test conducted shows no significant relationship between the (rural–urban) location of Irish WISEs and the gender of their volunteers (U = 13,058, p = 0.96).

Table 12.

WISEs’ volunteers according to gender distribution.

In terms of age distribution of volunteers, the majority of volunteers in WISEs are more than 50 years old, with this figure increasing to 65.1% in rural areas compared to 50.4% in urban areas. The non-parametric test confirms a statistically significant relationship between urban and rural WISEs and the age of volunteers, particularly for the age groups 30–50 and over 50 (Table 13). This prevalence of volunteers over 50, especially in rural areas, reflects the differences in the mean age within rural and urban areas of Ireland []. Older volunteers may bring a wealth of experience to WISEs but may also pose challenges for WISEs in terms of ensuring intergenerational renewal strategies aimed at potentially bridging the gap between older and younger people.

Table 13.

WISEs volunteers according to age distribution.

4.2.4. Income Generation

Annual income for Irish WISEs varies greatly from organisations with low-income levels below €100,000 to those generating over €1 M annually (Table 14). Those WISEs based and operating in rural areas are mostly concentrated within the lower income categories, with one-quarter (25.9%) generating below €100,000 and one-third (33.3%) between €100,000 and €250,000. In contrast, only 12.8% of urban WISEs generate below €100,000 annually and 19.2% generate over €1 M. The non-parametric test conducted confirms a statistically significant difference between rural and urban WISEs in the lowest (below €100,000) and highest (>€1 M) income categories. The significant differences in annual income between rural and urban WISEs indicate a higher contribution to income generation of urban WISEs, which reflects the usually stronger environment of urban areas in terms of access to markets and users/customers.

Table 14.

WISEs’ annual income (2021).

Our findings unveil statistically significant relationships between WISEs’ spatial locations and their contribution towards impact in different aspects such as reach/focus of their activities, employment, volunteers, and income generation. Our analysis shows that rural WISEs’ contributions are significantly higher in terms of their local focus and in providing employment and volunteer opportunities for people over 50 than their urban counterparts. On the other hand, urban WISEs show significantly greater contributions in terms of employment and income generation than their rural counterparts.

5. Discussion

WISEs, fast becoming the most dominant form of social enterprise globally, are typically characterised by a duality of objectives, including the integration of at-risk groups in the production and delivery of essential goods and services. Their embedded and collaborative structures, combining a multiplicity of resources and a strong social mission make them a form of social innovation, delivering responses to contemporary challenges [,]. As previously outlined, much of the research on WISEs to date has neglected the spatial dimension of this form of social innovation and, in particular, the similarities and differences that might exist between WISEs operating in rural and urban areas. This is particularly relevant in a country like Ireland, which is predominantly rural and where WISEs have evolved as the dominant social enterprise model to date, largely in response to tackling unemployment and meeting the needs of disadvantaged urban and rural communities []. The purpose of this paper has been to address this ‘spatial’ gap in knowledge by analysing the similarities and differences in the characteristics and contributions towards impact using data from a national survey of 336 Irish WISEs distributed across both rural and urban locations.

Our analysis shows how the characteristics of WISEs, related to their longevity, legal and governance form, multiactivity nature, and income diversification, are rather similar in Irish rural and urban WISEs. Our results confirm that WISEs are a distinctive type of organisation [] and form of social innovation, regardless of the spatial (urban–rural) settings in which they are based and operate []. However, our analysis also sheds some novel insights into the subtle differences between urban and rural WISEs in terms of the reach of their activities (in particular, their local focus), the extent of employment creation and their capacity to generate income. These differences are rather related to the contribution towards impact contributions of WISEs in their communities.

In relation to the greater local focus of rural WISEs, our analysis aligns with previous qualitative research on rural social enterprises conducted in Ireland, Austria, and Poland that show the relevance of local embeddedness and focus of these organisations [,]. This greater local focus together with the lower capacity of WISEs in rural areas to generate employment and income to the same extent as their urban counterparts support the findings of Steiner and Teasdale [], which suggest that the traditional focus on developing economies of scale (scale-up strategies) might not be adequate for unlocking the potential of social enterprises in rural areas. In this regard, our findings suggest that the contribution towards impact of rural WISEs is more aligned with the concept of scaling deep [], referring to a change in the norms and ways of doing things rather than having a great impact in absolute numbers.

Our findings related to the differences between rural and urban WISEs’ contributions to employment and income generation (with urban organisations reporting significantly higher numbers) show how this influence is context sensitive. In this regard, while urban WISEs often have access to a dense, diverse pool of volunteers, younger and more skilled employees, as well as a variety of potential revenue and resource streams [], rural WISEs, and especially those in remote and/or marginalised areas, do not tend to have the same access to such resources at the same degree due to weaker labour markets, a more ageing population, and more distant/lower political power [,,]. In terms of impact assessment, some studies have highlighted the relevance of context sensitive indicators related to social enterprises acting in developed and developing countries []. The findings from our study suggest that impact assessments should also be sensitive to rural and urban spaces as structural features of these areas, such as, for example, the age structure of the population and the local/regional labour market, influence WISEs’ capacity to contribute to social innovations.

Our results show WISEs’ capacity to mobilise volunteers, thus demonstrate their relevance in both rural and urban settings in the development of social capital [,]. However, contrary to the significant differences in terms of employment creation and income generation between rural and urban WISEs, our findings do not show a statistically significant difference in terms of volunteer numbers between rural and urban WISEs. In this regard, our findings suggest that despite structural differences in terms of access to larger population numbers in urban settings, the tradition of mutual self-help and a sense of community in Irish rural settings are key factors in the mobilisation of volunteers, which in turn reinforce the development of social capital in rural areas [,]. Additionally, volunteers are not only likely to bring diverse skills and experiences to WISEs, fostering capacity building within organisations [], but their involvement also suggests opportunities for community engagement and participation. Leveraging volunteer support could enhance organisational capacity of WISEs, forge community connections, and extend the reach and impact of WISE initiatives.

Finally, our research is not absent of limitations. First, our study is confined to Ireland and thus results apply to this country; however, further comparative studies of social innovative organisations, such as WISEs within different EU rural and urban areas, constitute an avenue for future research. Second, studies that incorporate longitudinal data and counterfactual evidence (experimental designs, for instance), conduct regression analysis for assessing the impact of WISEs in rural and urban settings, and incorporate spatially sensitive indicators for impact assessment represent others research avenues that can overcome some of the limitations of this study. Third, although our study draws conclusions for urban and rural WISEs, a greater level of granularity that considers greater spatial heterogeneity within rural areas, for example, those in remote locations versus other close to cities, and heterogeneity within urban areas, for example, towns and capital cities, constitutes another potential avenue for further research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.O. and M.O.; methodology, L.O. and M.J.R.-R.; formal analysis, L.O.; data curation, L.O.; writing—original draft preparation, L.O., M.J.R.-R., M.O. and G.C.; writing—review and editing, L.O., M.J.R.-R., M.O. and G.C.; visualization, L.O. and M.J.R.-R.; funding acquisition, L.O. and M.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Department of Rural and Community Development, Government of Ireland-National University of Ireland Postdoctoral Fellowship in Rural Development 2022.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are not made publicly available due to privacy/GDPR.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the editors of this Special Issue, the three anonymous reviewers and editor of Societies.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Normality Test (Shapiro-Wilk) According to Observed Variable.

Table A1.

Normality Test (Shapiro-Wilk) According to Observed Variable.

| W | p | |

|---|---|---|

| Total Employment | 0.450 | <0.0001 |

| Female workforce | 0.960 | <0.0001 |

| Volunteers (including Board Members) | 0.536 | <0.0001 |

| Female volunteers | 0.989 | 0.0155 |

| <30 years old volunteers | 0.534 | <0.0001 |

| 30–50 years old volunteers | 0.943 | <0.0001 |

| >50 years old volunteers | 0.941 | <0.0001 |

| Number of activities | 0.728 | <0.0001 |

| Total Income 2021 | 0.413 | <0.0001 |

Note. A low p-value suggests a violation of the assumption of normality.

Notes

| 1 | This article does not address the challenges of longitudinal data and counterfactual evidence. Thus, we use ‘contribution towards impact’ rather than impact per se to acknowledge the limitations of this study in the attribution of long-term impact to the actions of the WISEs studied. |

| 2 | The full questionnaire form is accessible at: https://www.gov.ie/en/publication/b30e5-social-enterprises-in-ireland-a-baseline-data-collection-exercise/ accessed on 12 March 2024. The questionnaire forms part of a wider research aimed at establishing a Baseline Data Collection of Social Enterprises in Ireland. Two of the authors of this paper are part of a team undertaking that wider research. |

| 3 | The Shapiro–Wilk test is a parametric method used to determine if a sample follows a normal distribution. Its null hypothesis assumes normality. The test involves comparing observed sample data with expected values under the assumption of normality, using a statistic called W. A value closer to one indicates greater consistency with a normal distribution; a low p-value suggests non-normality, while a higher p-value suggests consistency with a normal distribution []. |

| 4 | Non-parametric tests are commonly used in the social science and management research. These tests are used with nominal and ordinal variables. Contrary to parametric tests, non-parametric tests do not require that the sample be drawn from a population that follows a normal distribution. |

| 5 | Cooperatives in Ireland are usually legally registered as Industrial and Provident Societies. |

References

- National Disability Authority. NDA Factsheet 2: Employment and Disability. Available online: https://nda.ie/publications/nda-factsheet-2-employment (accessed on 12 March 2024).

- O’Hara, P.; O’Shaughnessy, M. Social Enterprise in Ireland State Support Key to the Predominance of Work Integration Social Enterprise (WISE). In Social Enterprise in Western Europe: Theory, Models and Practice; Defourny, J., Nyssens, M., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 112–130. ISBN 978-0-429-05514-0. [Google Scholar]

- O’Shaughnessy, M.; Christmann, G.; Richter, R. Introduction. Dynamics of Social Innovations in Rural Communities. J. Rural Stud. 2023, 99, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bock, B.B. Rural Marginalisation and the Role of Social Innovation; A Turn Towards Nexogenous Development and Rural Reconnection. Sociol. Rural. 2016, 56, 552–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, R.; Christmann, G.B. On the Role of Key Players in Rural Social Innovation Processes. J. Rural Stud. 2023, 99, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moulaert, F.; MacCallum, D.; Mehmood, A.; Hamdouch, A. (Eds.) The International Handbook on Social Innovation: Collective Action, Social Learning and Transdisciplinary Research; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK; Northampton, MA, USA, 2014; ISBN 978-1-78254-559-0. [Google Scholar]

- Avelino, F.; Wittmayer, J.M.; Pel, B.; Weaver, P.; Dumitru, A.; Haxeltine, A.; Kemp, R.; Jørgensen, M.S.; Bauler, T.; Ruijsink, S.; et al. Transformative Social Innovation and (Dis)Empowerment. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2019, 145, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzichristos, G.; Hennebry, B. Social Innovation in Rural Governance: A Comparative Case Study across the Marginalised Rural EU. J. Rural Stud. 2023, 99, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCallum, D.; Moulaert, F.; Hillier, J.; Vicari Haddock, S. (Eds.) Social Innovation and Territorial Development; Ashgate: Farnham, UK, 2009; ISBN 978-0-7546-7233-3. [Google Scholar]

- Noack, A.; Federwisch, T. Social Innovation in Rural Regions: Older Adults and Creative Community Development. Rural Sociol. 2020, 85, 1021–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooney, K.; Nyssens, M.; O’Shaughnessy, M.; Defourny, J. Public Policies and Work Integration Social Enterprises: The Challenge of Institutionalization in a Neoliberal Era. Nonprofit Policy Forum 2016, 7, 415–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pel, B.; Bauler, T. A Transitions Studies Perspective on the Social Economy: Exploring Institutionalization and Capture in Flemish “Insertion” Practices. Ann. Public Coop. Econ. 2017, 88, 279–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooney, K.; Nyssens, M.; O’Shaughnessy, M. Work Integration and Social Enterprises. In Encyclopedia of the Social and Solidarity Economy: A Collective Work of the United Nations Inter-Agency Task Force on SSE (UNTFSSE); Yi, I., Ed.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK; Northampton, MA, USA, 2023; pp. 215–222. ISBN 978-1-80392-091-7. [Google Scholar]

- Fleuret, S.; Atkinson, S. Wellbeing, Health and Geography: A Critical Review and Research Agenda. N. Z. Geogr. 2007, 63, 106–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmer, J.; Kamstra, P.; Brennan-Horley, C.; De Cotta, T.; Roy, M.; Barraket, J.; Munoz, S.-A.; Kilpatrick, S. Using Micro-Geography to Understand the Realisation of Wellbeing: A Qualitative GIS Study of Three Social Enterprises. Health Place 2020, 62, 102293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moulaert, F.; Ailenei, O. Social Economy, Third Sector and Solidarity Relations: A Conceptual Synthesis from History to Present. Urban Stud. 2005, 42, 2037–2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defourny, J.; Nyssens, M. Defining Social Enterprise. In Social Enterprise: At the Crossroads of Market, Public Policies and Civil Society; Nyssens, M., Adam, S., Johnson, T., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 3–28. ISBN 978-0-415-37879-6. [Google Scholar]

- Van Opstal, W.; Borms, L. Work Integration Ambitions of Startups in the Circular Economy. Ann. Public Coop. Econ. 2023, 95, 477–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RREUSE. Job Creation in the Re-Use Sector: Data Insights from Social Enterprises. Available online: https://www.rreuse.org/wp-content/uploads/04-2021-job-creation-briefing.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- Nachemson-Ekwall, S. Unemployed Marginalised Migrant Women Work Integrating Social Enterprises as a Solution. In Proceedings of the CIRIEC, Valencia, Spain, 13–15 June 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Nyssens, M.; Adam, S.; Johnson, T. (Eds.) Social Enterprise: At the Crossroads of Market, Public Policies and Civil Society; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2006; ISBN 978-0-415-37878-9. [Google Scholar]

- European Network of Social Integration Enterprises. ENSIE’s WISEs Database. Available online: https://ensie.devexus.net/map (accessed on 7 March 2024).

- Roy, M.J.; Donaldson, C.; Baker, R.; Kerr, S. The Potential of Social Enterprise to Enhance Health and Well-Being: A Model and Systematic Review. Soc. Sci. Med. 2014, 123, 182–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macaulay, B.; Roy, M.J.; Donaldson, C.; Teasdale, S.; Kay, A. Conceptualizing the Health and Well-Being Impacts of Social Enterprise: A UK-Based Study. Health Promot. Int. 2017, 33, 748–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barraket, J. Fostering the Wellbeing of Immigrants and Refugees? In Social Enterprise: Accountability and Evaluation around the World; Denny, S., Seddon, F.A., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 102–119. ISBN 978-0-415-62609-5. [Google Scholar]

- Borzaga, C.; Carini, C.; Galera, G.; Nogales, R.; Chiomento, S. Social Enterprises and Their Ecosystems in Europe: Comparative Synthesis Report; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2020; ISBN 978-92-79-97734-3. [Google Scholar]

- Defourny, J.; Nyssens, M. Conceptions of Social Enterprise in Europe: A Comparative Perspective with the United States. In Social Enterprises: An Organizational Perspective; Gidron, B., Hasenfeld, Y., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 71–90. ISBN 978-0-230-35879-9. [Google Scholar]

- Gardin, L. Les Initiatives Solidaires. La Réciprocité Face au Marché et à l’Etat; Erès: Paris, France, 2006; ISBN 978-2-7492-0670-7. [Google Scholar]

- Slitine, R.; Chabaud, D.; Richez-Battesti, N. Beyond Social Enterprise: Bringing the Territory at the Core. J. Bus. Res. 2024, 176, 114577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahim, A.; Rangan, V.K. What Impact? A Framework for Measuring the Scale and Scope of Social Performance. Calif. Manage. Rev. 2014, 56, 118–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krlev, G.; Mildenberger, G.; Then, V. Social Impact Measurement. In Encyclopedia of Social Innovation; Howaldt, J., Kaletka, C., Eds.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK; Northampton, MA, USA, 2023; pp. 433–437. ISBN 978-1-80037-334-1. [Google Scholar]

- Hynes, B. Growing the Social Enterprise—Issues and Challenges. Soc. Enterp. J. 2009, 5, 114–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haugh, H.M.; Talwar, A. Linking Social Entrepreneurship and Social Change: The Mediating Role of Empowerment. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 133, 643–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, Z.C.S.; Ho, A.P.Y.; Tjia, L.Y.N.; Tam, R.K.Y.; Chan, K.T.; Lai, M.K.W. Social Impacts of Work Integration Social Enterprise in Hong Kong—Workfare and Beyond. J. Soc. Entrep. 2019, 10, 159–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, R. Social Innovation as a Collaborative Concept. Innov. Eur. J. Soc. Sci. Res. 2017, 30, 388–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seddon, F.; Hazenberg, R.; Denny, S. Reintegrating Socially Excluded Individuals through a Social Enterprise Intervention. Soc. Enterp. J. 2014, 10, 222–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertotti, M.; Harden, A.; Renton, A.; Sheridan, K. The Contribution of a Social Enterprise to the Building of Social Capital in a Disadvantaged Urban Area of London. Community Dev. J. 2012, 47, 168–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang, R.; Fink, M. Rural Social Entrepreneurship: The Role of Social Capital within and across Institutional Levels. J. Rural Stud. 2019, 70, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olmedo, L.; O’Shaughnessy, M. A Substantive View of Social Enterprises as Neo-Endogenous Rural Development Actors. Volunt. Int. J. Volunt. Nonprofit Organ. 2023, 34, 209–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barraket, J.; Eversole, R.; Luke, B.; Barth, S. Resourcefulness of Locally-Oriented Social Enterprises: Implications for Rural Community Development. J. Rural Stud. 2019, 70, 188–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina Munro, M.; Belanger, C. Analyzing External Environment Factors Affecting Social Enterprise Development. Soc. Enterp. J. 2017, 13, 38–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vestrum, I.; Rasmussen, E.; Carter, S. How Nascent Community Enterprises Build Legitimacy in Internal and External Environments. Reg. Stud. 2017, 51, 1721–1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.M.; McColl, J. Contextual Influences on Social Enterprise Management in Rural and Urban Communities. Local Econ. J. Local Econ. Policy Unit 2016, 31, 572–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, S.; Healey, P. A Sociological Institutionalist Approach to the Study of Innovation in Governance Capacity. Urban Stud. 2005, 42, 2055–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, M. What’s so New about New Municipalism? Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2021, 45, 317–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovannini, M. Solidarity Economy and Political Mobilisation: Insights from Barcelona. Bus. Ethics Eur. Rev. 2020, 29, 497–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraff, H.; Jernsand, E.M. The Roles of Social Enterprises in a Swedish Labour Market Integration Programme—Opportunities and Challenges for Social Innovation. Soc. Enterp. J. 2021, 17, 203–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jessop, B. Liberalism, Neoliberalism, and Urban Governance: A State–Theoretical Perspective. Antipode 2002, 34, 452–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, R. Innovations at the Edge: How Local Innovations Are Established in Less Favourable Environments. Urban Res. Pract. 2021, 14, 502–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olmedo, L.; Van Twuijver, M.; O’Shaughnessy, M. Rurality as Context for Innovative Responses to Social Challenges—The Role of Rural Social Enterprises. J. Rural Stud. 2023, 99, 272–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, A.; Teasdale, S. Unlocking the Potential of Rural Social Enterprise. J. Rural Stud. 2019, 70, 144–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CSO. Business Demography 2020. Available online: https://www.cso.ie/en/statistics/enterprisestatistics/businessdemography/businessdemographyupdatemay2023/ (accessed on 21 January 2024).

- Moore, M.-L.; Riddell, D.; Vocisano, D. Scaling Out, Scaling Up, Scaling Deep: Strategies of Non-Profits in Advancing Systemic Social Innovation. J. Corp. Citizsh. 2015, 2015, 67–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraska-Miller, M. Nonparametric Statistics for Social and Behavioral Sciences; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2014; ISBN 978-0-367-37910-0. [Google Scholar]

- CSO. Census of Population 2016—An Age Profile of Ireland. Available online: https://www.cso.ie/en/releasesandpublications/ep/p-cp3oy/cp3/urr/ (accessed on 30 May 2024).

- Defourny, J.; Nyssens, M.; Brolis, O. Testing Social Enterprise Models Across the World: Evidence From the “International Comparative Social Enterprise Models (ICSEM) Project”. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2021, 50, 420–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, R. Rural Social Enterprises as Embedded Intermediaries: The Innovative Power of Connecting Rural Communities with Supra-Regional Networks. J. Rural Stud. 2019, 70, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helleputte, C. Assessment of (Social) Impact and Impact of Assessment in Social Enterprises: A Transdisciplinary Research. Ph.D. Thesis, UCLouvain, Louvain-la-Neuve, Belgium, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Hulgard, L.; Spear, R. Social Entrepreneurship and the Mobilization of Social Capital in European Social Enterprises. In Social Enterprise; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2006; ISBN 978-0-203-94690-9. [Google Scholar]

- Falk, I.; Kilpatrick, S. What Is Social Capital? A Study of Interaction in a Rural Community. Sociol. Rural. 2000, 40, 87–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).