Comparative Study on National Policies and Educational Approaches toward Regional Revitalization in Japan and South Korea: Aiming to Achieve the Sustainable Development Goals

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Education and the SDGs

1.2. Local Sustainability Issues in Japan

1.3. Local Sustainability Issues in South Korea

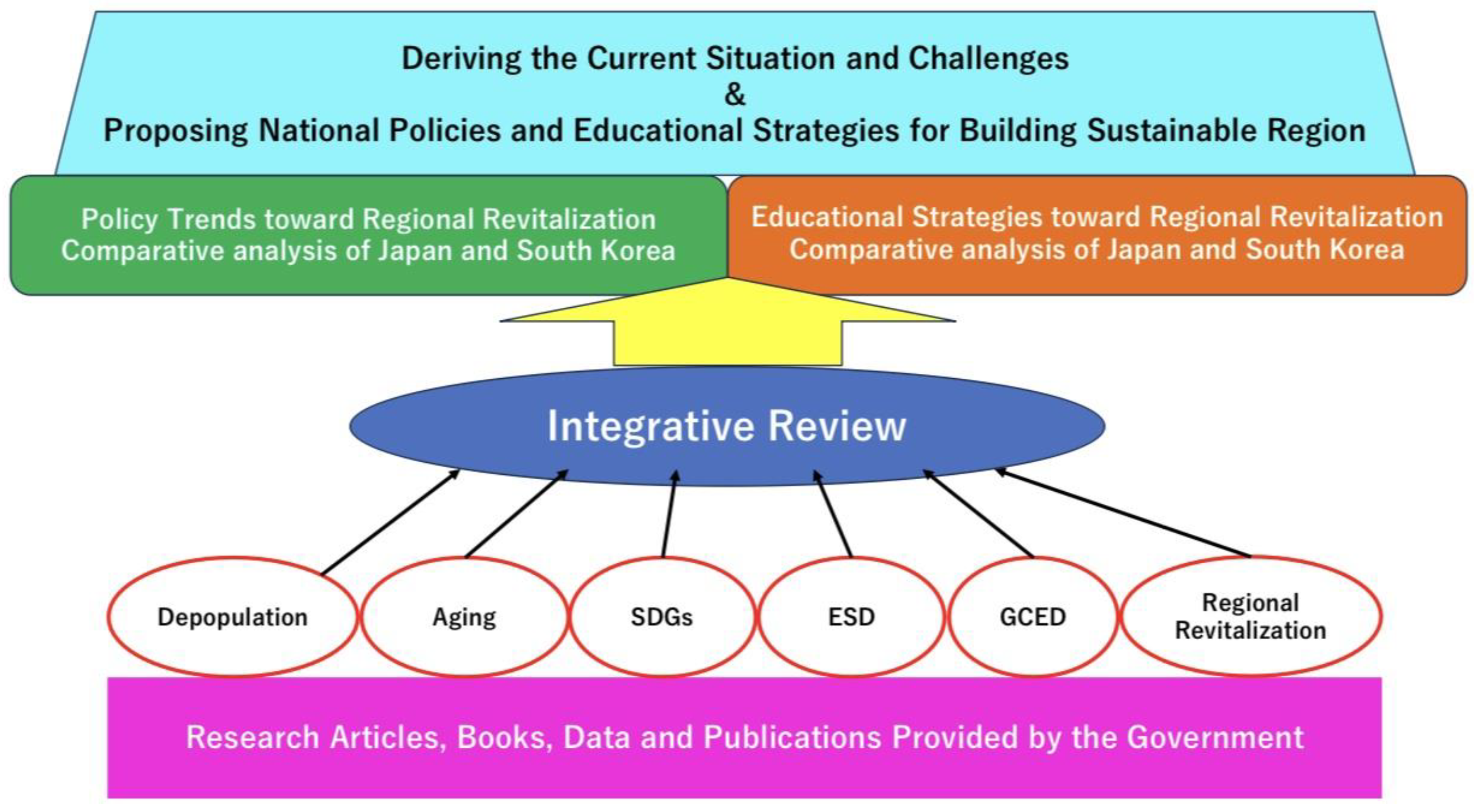

2. Research Method and Originality

2.1. Research Design

2.2. Literature Search

3. Comparative Analysis of Regional Revitalization Policy and SDG Education

3.1. Consideration of Regional Revitalization Policy

3.1.1. Japan

3.1.2. South Korea

3.2. Characteristics of SDG Education

3.2.1. Japan

3.2.2. South Korea

4. Results of Comparative Analysis

5. Conclusions, Discussion, and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- The Future Seen from the United Nations “World Population Statistics”, Sumitomo Mitsui Banking Corporation Monthly Report, November 2022. Available online: https://www.smtb.jp/-/media/tb/personal/useful/report-economy/pdf/127_2.pdf (accessed on 27 April 2023).

- Oh, S. Comparative Study of Multicultural Education in Japan and Korea: Through Comparison of School Education, Social Education, and Community Efforts, 1st ed.; Department of Education: Gakubunnsya, Japan, 2021; pp. 3–145. [Google Scholar]

- Google Scholar. Available online: https://scholar.google.co.jp/schhp?hl=ja (accessed on 27 July 2023).

- Kyobo Library Scholar. Available online: https://scholar.kyobobook.co.kr/main (accessed on 27 July 2023).

- Rieckmann, M. Education for Sustainable Development Goals: Learning Objectives; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2017; Available online: https://books.google.co.jp/books?hl=ja&lr=lang_ja|lang_en&id=Fku8DgAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PP4&dq=Education+for+sustainable+development+goals:+Learning+objectives&ots=ZNJApAbehf&sig=Ew_XE37VBF_cYgz1Vqjaw5vaeBw#v=onepage&q=Education%20for%20sustainable%20development%20goals%3A%20Learning%20objectives&f=false (accessed on 27 April 2023).

- Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology. Development of Leaders for SDGs (ESD) Promotion Project. Available online: https://www.mext.go.jp/unesco/018/index.htm (accessed on 27 April 2023).

- Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology. Education for Sustainable Development. Available online: https://www.mext.go.jp/en/unesco/title04/detail04/sdetail04/1375695.htm (accessed on 27 April 2023).

- Bullock, C.; Hitzhusen, G. Participatory development of key sustainability concepts for dialogue and curricula at The Ohio State University. Sustainability 2015, 7, 14063–14091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurie, R.; Nonoyama-Tarumi, Y.; Mckeown, R.; Hopkins, C. Contributions of education for sustainable development (ESD) to quality education: A synthesis of research. J. Educ. Sustain. Dev. 2016, 10, 226–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics Bureau, Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications. Elderly Population. Available online: https://www.stat.go.jp/data/topics/topi1291.html (accessed on 27 April 2023).

- Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications. List of Depopulated Municipalities. Available online: https://www.soumu.go.jp/main_content/000807168.pdf (accessed on 27 April 2023).

- Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications Local Government Administration Bureau Depopulation Countermeasures Office. 2011 Edition “Current Situation of Depopulation Countermeasures”. Available online: https://www.soumu.go.jp/main_content/000186144.pdf (accessed on 27 April 2023).

- Kantei, SDGs Action Plan 2021 Priority Items. Available online: https://www.kantei.go.jp/jp/singi/sdgs/entakukaigi_dai11/siryou5.pdf (accessed on 27 April 2023).

- Tamura, K. Inter-Prefectural Population Migration Associated with Entering University; Asian Growth Research Institute: Kitakyushu, Japan, 2017; Available online: https://agi.repo.nii.ac.jp/?action=repository_uri&item_id=237&file_id=22&file_no=1 (accessed on 16 April 2023).

- Kim, D.; Yamazaki, J. Improvement of Resident Capacity by Associating People or Groups Inside and Outside Village for Community Development: Focused on Actions of Alps village Steering Committee in Cheonjang-ri Located in Depopulated Rural Area of Korea. J. Rural. Plan. Assoc. 2013, 32, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yim, S.; Lee, J.; Ryu, C. A Study on Job Characteristics, Job Satisfaction, and Life Quality of Aging Workforce: Focusing on the Mediating Effect of Regular and Non-regular Workers. J. Korea Acad.-Ind. Coop. Soc. 2021, 22, 199–211. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, J. A Study on the Legal Issues of Local Finance with Advent of the Age of Declining Population. J. Korean Auton. Law Assoc. 2020, 20, 3–27. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, Y. Fundamental research for the introduction of the “marginal village policy” to cope with the depopulation and aging population. Chungnam Res. Inst. Strateg. Res. 2013, 7, 17. [Google Scholar]

- Li, K.; Kaneko, J.; Komai, N. Vital Statistics in South Korea and Measures to Revitalize Local Cities. Geogr. Space 2018, 10, 199–208. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder, H. Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 104, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiko, H. Population indicators in Japan, China and South Korea and trends in countermeasures against the declining birthrate and aging population. Health Labor Stand. Sci. Res. Rep. 2021, 1, 174–182. [Google Scholar]

- Kuroda, T. Demographic study of the aging phenomenon 1. In Research on Population Problems; National Research Institute of Population and Social Security Research: Tokyo, Japan, 1955; pp. 8–62. [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka, M. Accumulation of human capital through recurrent education. Econ. Anal. 2017, 196, 49–81. [Google Scholar]

- Cabinet Secretariat. [Revised] Soft Growth Strategy: Making Abenomics More Familiar. Available online: https://www.kantei.go.jp/jp/topics/2014/leaflet_seichosenryaku.pdf (accessed on 27 April 2023).

- Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare “General Employment Placement Situation (August 2016)”. 2016. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/houdou/0000137408.html (accessed on 27 April 2023).

- Lee, Y.; Sugiura, H. Determinants of Returning to Rural Areas and Their Promotion Measures: A Case Study of Hirosaki City, Aomori Prefecture (Special Issue: Population Decline and Local Economy). Financ. Rev. 2017, 53, 123–143. [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka, M. Economic impact of recurrent education. J. Jpn. Labor Res. 2020, 8, 51–62. [Google Scholar]

- Sunahara, M.; Kim, M. Historical changes in recurrent education and its impact on the Japanese economy: Focusing on institutions of higher education. Educ. Econ. Res. 2022, 1, 50–61. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare. Recurrent Education. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/newpage_18817.html (accessed on 28 April 2023).

- Morikawa, H. Regional Revitalization Policy in Japan and Its Problems. Jpn. J. Hum. Geogr. 2020, 72, 299–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morikawa, H. Regional characteristics of the elderly population based on the 2010 and 2015 census data. Geogr. Sci. 2018, 73, 35–49. [Google Scholar]

- Cabinet Office. “Cabinet Decision: Changes to the Comprehensive Strategy for Vitalizing Towns, People, and Jobs”. 2015. Available online: http://www.kantei.go.jp/jp/singi/sousei/info/pdf/h27-12-24-shiryou2.pdf (accessed on 28 April 2023).

- Cabinet Office. “Revitalization of Towns, People, and Jobs -Regional Revitalization-”. 2019. Available online: http://www.kantei.go.jp/jp/singi/sousei/mahishi_index.html (accessed on 28 April 2023).

- Lee, S.L. Labor force shortage projection and policy implications: Impact of demographic transition in Korea. Korea J. Popul. Stud. 2012, 35, 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Park, Y. The Relationship between Residential Distribution of Immigrants and Crime in South Korea. J. Distrib. Sci. 2018, 16, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Official Blog of the Ministry of Public Administration and Safety “Local Government Foreign Resident Status”. Available online: http://blog.naver.com/mopaspr/222129965805 (accessed on 28 April 2023).

- Eom, D.W. Population Aging and Wage Structure: An Empirical Study of Cohort Size Effect on Korean Male Worker since 1990. Korea J. Popul. Stud. 2008, 31, 75–97. [Google Scholar]

- Ryu, D.H. An Empirical Study on the Effects of Fertility Rate and Female Labor Supply on Economic Potential. Korea J. Popul. Stud. 2008, 31, 27–54. [Google Scholar]

- Takayasu, Y. Consideration on Employment of Foreign Workers in Korean Agriculture. Korean Econ. Res. 2020, 17, 37–50. [Google Scholar]

- Minami, S.; Kim, S.; Sasakawa, K. Educational Care for Foreigners (Immigrants/Migrant Workers) in South Korea. Kanazawa Univ. Fac. Econ. J. 2000, 20, 117–152. [Google Scholar]

- Haruki, I. The Development and Background of Foreign Worker Policies in South Korea. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2011, 28, 93–106. [Google Scholar]

- Haruki, I. Korean Language Education by Unskilled Foreign Workers in South Korea and its Challenges. Korean Econ. Res. 2022, 19, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, S. Efforts in social education from the perspective of multicultural education. In Bulletin of the Graduate School of Education; Waseda University: Tokyo, Japan, separate volume; 2021; Volume 1, pp. 57–65. Available online: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/286927711.pdf (accessed on 28 April 2023).

- Japan Institute for Labor Policy and Training. “Promoting and Supporting UIJ Turns and Revitalizing Local Areas: Results of a Survey on Regional Migration among Young People”. JILPT Survey Series No. 152. 2016. Available online: https://www.jil.go.jp/institute/research/2016/documents/152.pdf (accessed on 28 April 2023).

- Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications “Study Group on Future Immigration and Exchange Policies”. Available online: https://www.soumu.go.jp/main_sosiki/kenkyu/ijyuu_koryuu/index.html (accessed on 28 April 2023).

- Owada, J.; Kazami, S. Community value co-creation platform and local revitalization human resource development model by cause related population. In Proceedings of the International P2M Conference, Tokyo, Japan, 25 April 2020; pp. 239–253. Available online: https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/iappmproc/2020.Spring/0/2020.Spring_239/_pdf/-char/ja (accessed on 28 April 2023).

- Sugiyama, S. Local-oriented consciousness and career development among university students. Otaru Univ. Commer. Humanit. Res. 2012, 123, 123–140. [Google Scholar]

- Asaoka, Y. Environmental Education under Globalization and Education for Sustainable Development (ESD). Educ. Stud. 2005, 72, 530–543. [Google Scholar]

- Komura, S.; Kanai, T. Education in the future and the SDGs: What is learning in which students exercise their agency? Acad. Trends 2018, 23, 38–43. [Google Scholar]

- Nagaoka, M. SDGs: ESD and Regional Cooperation in Education for Sustainable Development and Kyosei. J. Kyosei Stud. 2018, 9, 34–43. [Google Scholar]

- Okubo, K.; Yu, J.; Osanai, S.; Serrona, K.R.B. Present Issues and Efforts to Integrate Sustainable Development Goals in a Local Senior High School in Japan: A Case Study. J. Urban Manag. 2021, 10, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osanai, S.; Yu, J. Teaching the Effectiveness of Integrated Studies and Social Engagement: A Case Study on SDG Education in Depopulated Areas in Japan. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hida, D.; Hida, Y. Population Declining Society and High School Attractiveness Project: Educational Sociology of Regional Human Resource Development; Akashi Bookstore: Akashi, Japan, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Banjo, K. How can we create a community where people can grow? From the case of the Hida City Academy Plan. Annu. Rep. Jpn. Soc. Lifelong Educ. Editor. Comm. Jpn. Soc. Lifelong Educ. Annu. Rep. 2022, 43, 95–115. [Google Scholar]

- Abe, O. Regional Revitalization Power of ESD: 9 Practices for Building a Sustainable Society and Developing Human Resources; Joint Publishing: Hong Kong, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Naito, M.; Uchida, M. Efforts of local governments: Efforts related to the UNESCO Learning Cities Global Network in Okayama City. Annu. Rep. Jpn. Soc. Learn. Sociol. 2019, 16, 24–27. [Google Scholar]

- Masuda, H.; Kawakubo, S.; Okitasari, M.; Morita, K. Exploring the role of local governments as intermediaries to facilitate partnerships for the Sustainable Development Goals. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 82, 103883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakato, Y. Revitalization of the Japanese Economy and Depopulated Areas; University Education Press: Tokyo, Japan, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ishimaru, A. Awareness of SDGs practice of university students. Proc. Res. Conf. Jpn. Assoc. Reg. Revital. 2020, 12, 146–149. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, S. Efforts for Multicultural Education in Multicultural Homes and Families in South Korea: Focusing on Trends in Education Policy. Int. Educ. 2017, 23, 134–139. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO Global Citizenship Education. Available online: https://en.unesco.org/themes/gced (accessed on 28 April 2023).

- Leite, S. Using the SDGs for global citizenship education: Definitions, challenges, and opportunities. Glob. Soc. Educ. 2022, 20, 401–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pashby, K.; Sund, L. Critical Global Citizenship Education in the Era of SDG 4.7: Discussing HEADSUP with Secondary Teachers in England, Finland and Sweden. The Bloomsbury Handbook of Global Education and Learning. 2020, 314. Available online: https://books.google.co.jp/books?hl=ja&lr=lang_ja|lang_en&id=4WjDDwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PA314&dq=Pashby,+K.,+%26+Sund,+L.+(2020).+Critical+Global+Citizenship+Education+in+the+Era+of+SDG+4.7:+Discussing+HEADSUP+with+Secondary+Teachers+in+England,+Finland+and+Sweden.+The+Bloomsbury+Handbook+of+Global+Education+and+Learning,+314.&ots=ZHhnnXjlW3&sig=Jz2NWYHP1lbBsV5ODJFD4PP21y8#v=onepage&q&f=false (accessed on 28 April 2023).

- Kobayashi, R. The Capabilities Pursued by UNESCO’s Global Citizenship Education: New Perspectives on Values Education in the Global Era. Ph.D. Thesis, Tamagawa University, Tokyo, Japan, 31 March 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, Y.; Morris, M.W.; Chiu, C.; Benet, V. Multicultural minds: A dynamic constructivist approach to culture and cognition. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ko, M. A Study of Korean Multicultural Families: Focusing on Children’s Education and Bilingualism; Bulletin of the Institute of Human Rights Studies; Kansai University: Suita, Japan, 2019; pp. 15–34. Available online: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/250302993.pdf (accessed on 28 April 2023).

- Kato, M. Reality of Employment Permit System in Korea as Seen from Field Survey: Brokers, Pre-arrival Debts, and Harsh Working Conditions Seen Even in “Front Door” Acceptance. Mitsubishi Ufj Research & Consulting, Policy Research Report. 2021. Available online: https://www.murc.jp/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/seiken_210514.pdf (accessed on 28 April 2023).

- Oh, S. Study on the Cooperation between the School and Home regarding Education for Children of Multicultural Families in Korea: Multicultural Education Policies and Efforts in Ansan City. Bull. Jpn. Soc. Soc. Educ. 2013, 49, 13–21. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, H.S. The Gaps between Values and Practices of Global Citizenship Education: A Critical Analysis of Global Citizenship Education in South Korea. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Massachusetts Amherst, Amherst, MA, USA, 2016; pp. 1–199. Available online: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1853&context=dissertations_2 (accessed on 28 April 2023).

- Noh, J.E. The legitimacy of Development Nongovernmental Organizations as Global Citizenship Education Providers in Korea. Educ. Citizsh. Soc. Justice 2019, 14, 241–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, E. “Immigrants in the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Place Where the Vulnerability of Japanese Society Revealed”. Akashi Bookst. Kokushikan J. Humanit. 2022, 3, 82–83. [Google Scholar]

- Koido, A.; Kamibayashi, C. special issue “Japanese Society and International Immigrants: Controversy over Acceptance of Immigrants, Realities 30 Years Later”. Social. Rev. 2018, 68, 468–478. [Google Scholar]

- Horie, Y. Current Status and Issues of Multicultural Education in Japan: “Educational Minorities” in Contemporary Japan. Bull. Fac. Educ. Bukkyo Univ. 2010, 9, 47–59. [Google Scholar]

| Elements Involved in Regional Revitalization | Japan | South Korea |

|---|---|---|

| Sustainability issues | Aging society with a declining birthrate | Aging society with declining birthrate |

| Issues related to local sustainability | Depopulation due to declining rural population | Depopulation due to declining rural population |

| Status of foreign resident | 2,823,565 people [71] | 4.3% of 51,779,203 people [36] |

| Characteristics of policies aimed at maintaining population | Not considering the introduction of immigrants from abroad to maintain the population | Introduction of immigrants from foreign countries to maintain the population |

| Management policy for measures for regional revitalization | Bottom-up measures implemented by local cities for regional revitalization | Top-down measures within the framework of urban renewal, including large cities for regional revitalization |

| Characteristics of SDG education efforts | Community-based collaborative education for solving local problems | GCED for Plural Identity Integration toward people with multiple cultures |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Osanai, S.; Yu, J. Comparative Study on National Policies and Educational Approaches toward Regional Revitalization in Japan and South Korea: Aiming to Achieve the Sustainable Development Goals. Societies 2023, 13, 210. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc13090210

Osanai S, Yu J. Comparative Study on National Policies and Educational Approaches toward Regional Revitalization in Japan and South Korea: Aiming to Achieve the Sustainable Development Goals. Societies. 2023; 13(9):210. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc13090210

Chicago/Turabian StyleOsanai, Shiori, and Jeongsoo Yu. 2023. "Comparative Study on National Policies and Educational Approaches toward Regional Revitalization in Japan and South Korea: Aiming to Achieve the Sustainable Development Goals" Societies 13, no. 9: 210. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc13090210

APA StyleOsanai, S., & Yu, J. (2023). Comparative Study on National Policies and Educational Approaches toward Regional Revitalization in Japan and South Korea: Aiming to Achieve the Sustainable Development Goals. Societies, 13(9), 210. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc13090210