Team Approaches to Addressing Sex Trafficking of Minors: Promising Practices for a Collaborative Model

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Development of Community-Based Responses

1.2. Community-Based Responses to Sex Trafficking

1.3. Community-Based Responses to Juvenile Justice System-Involved Minors Experiencing Sex Trafficking

- What are the benefits and challenges to collaboration with various community partners in social services, the justice system, and the child welfare system?

- What processes are being used in the juvenile justice response to trafficking, and how do practitioners perceive their efficacy?

2. Methods

2.1. Sample

Sample Recruitment

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

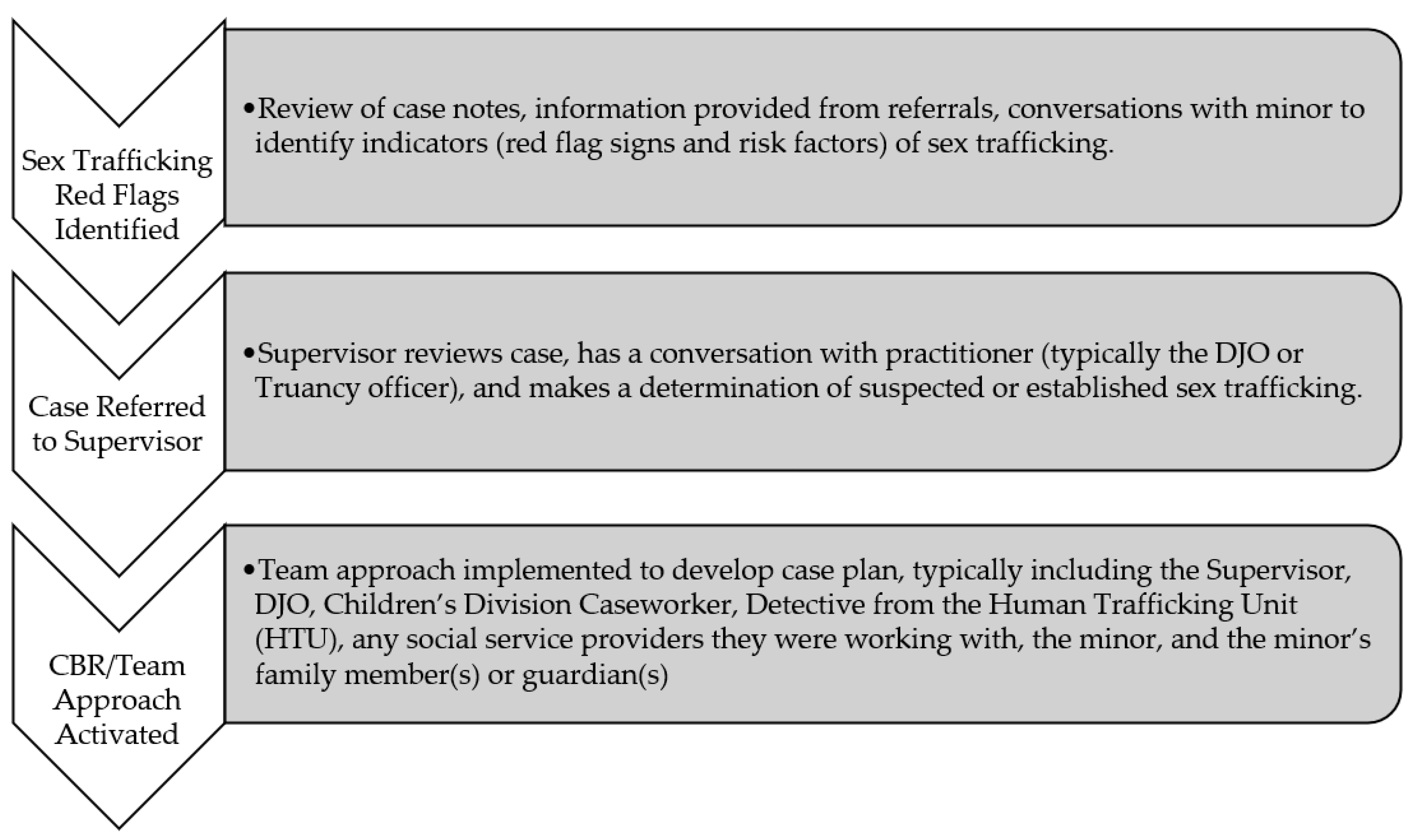

3.1. Processes Used in Study Site A

What’s the protocol? So, there’s a long form that the chief gave us a while back and I rarely use it because it’s so long. It’s a lot of information we don’t have. So, I’ll immediately talk to my supervisor if she’s here but then, the investigator, almost immediately, we shoot an email or a text or make a phone call and say, “Hey, I have this situation. Can we talk about it?…”

Internal Organizational Collaboration

Right, so, I actually got a call from somebody last night at 10:34. A kid at [High School] who had some trafficking concerns. So, I didn’t really know what to do with it. And so, you go and you get direction. I mean, supervisors give you direction anyway, but it’s helpful for clarity because with this stuff, you really don’t want to miss something. It’s kind of critical. I mean, attendance- that’s important. Trafficking is a different concern.

It’s scary to think about the stuff these kids go through. And so when you’re uncertain, you have got to have people and certainly the inner unit stuff is a good process before you even start talking to the police department and other people, just so you cover all your bases. You know, experience is important, especially if they’ve succeeded in helping the kid and stuff, it’s really important.

3.2. Benefits of Team Approach Used in Study Site A

I think when the child come in and see there’s a lot of people who have an interest in her and want to help her. And then, each of us have our own ideas of how to bring positive things to the team, because no one person thinks the same and everybody has different ideas, but if it can be brought to the team and we can all agree to it, I think that’s one of the things, you know—cause I think each team member has something to bring to the team, including the child herself.

3.2.1. Collaboration between Social Service Providers and DJOs

With the DJOs in [Study Site A], they have been very intentional…. And so they’ve been very good about, “Okay, let’s try to look at the gaps. What can we do?” Looking at it bigger than just like the courts, but how can we help supplement these other agencies? What grants can we bring into the city so that we have some different avenues. And little things like we’re talking to them even right now about could we set up some groups for their kids, some preventative measures so that even if kids haven’t been identified [e.g., suspected trafficking/high risk], they have these options where they can come here for services or we can go there for services. So I think they’ve been very intentional. And they’re very good about, their DJOs come and- I think this is important. They’re very good about coming to see the home and the program and wanting to know where they’re referring kids.

She’s just really good on working and making sure DJOs…they invite us to family support team meetings, they invite us to just about everything, and they’re really involved. In [Study Site B], I’ve only worked with a few, and it’s been a hit or miss. I’ll be honest with you, that the procedures are more defined in [Study Site A], or more…the enforcement and follow-through….Better involvement. So even if it’s on the detention side, the juvenile side, or if it’s on the protective custody side, I’ve seemed to have a better relationship because it’s more… I don’t know. I guess the enforcement of it is better…That’s a big part of it. They bring the whole team to the table, and they’re making sure that everybody’s talking…And the [Study Site A] is kind of DJO-led, and they have a really good system. It’s effective.

And they get the judges on board. And that’s the best part about the DJO’s, is they get the judges on board. And so they’re the ones who educate the judges on trafficking and saying, “Hey, here’s the situation that we have, and we need to look at it differently.” And then when we’re in court and the attorney for the court presents, “The DJO is saying this,” and they have their report, the judges are asking different questions now, versus just looking at behavior. They’re looking at the whole scope. So the DJO is that liaison with that too, with the court. And so that helps a lot with making sure that sentences aren’t punitive, or they’re really looking at parents, or looking at the actual danger in the situation of the trafficking.

3.2.2. Collaboration between Social Service Providers and Judges

Where a lot of times, judges go based on what a DJO recommends…but it seems like they’re very active in like "Let’s look at all the pieces and see what we can do to get the services for the kids." So it looks very different and recognizing them as a victim so that was something that I’ve seen just in the courts as a whole from everyone I’ve interacted with. It’s how do we get the services for the kids that they need.

3.2.3. Collaboration between the Juvenile Court and Investigators

Dedication to what you’re doing. Trying to help save these kids. To me, that’s it. Just being dedicated to what you’re doing, knowing that you’re doing something to help somebody. I mean, that’s… We’re in helping professions. And that to me makes all the difference.

Mr. Stark, and so, I definitely like the way he does his follow-ups, and if there’s something pertinent, of course he’s going to follow up…Because it actually happens. You know, and so sometimes it’s just a professional courtesy to say hey okay, so we just took this next step with your client. There’s nothing you can do about this next step we took, all right, you can’t add to it, you can’t stop it, take away from it. But I thought you should know this just in case it comes up when you meet with the parent or the kid. And so that stuff, in that respect, it’s important.

With the cases I had, I describe it as very good. They [detectives] were very helpful. They kept us in contact what was going on. I was able to keep in contact with the prosecuting attorney, also with the FBI, and all of those that was involved. So they were very supportive.

I think we trust them [Study Site A detectives], they trust us, and having that good rapport, whether it starts from the police department or what not. Having that good rapport relationship with them- it helps us to build that relationship, that positive relationship, so that we can see a case through.

Yeah, I think a lot of working together with other organizations, having resources, and knowing people in those resources that you can call and contact and open lines of communications so that when we do have victims, we know where to send them. We can find places for them to go…

That’s big. Trust is big with juvenile courts because you’re looking at trust on two sides. You’re looking at trust on, not just the attorney side, but you’re looking at trust on the defense attorney’s side to know that your goal is not to have their client incarcerated. When the defense attorney’s know what you’re ultimate goal is in understanding that’s what you’re looking at, that is the most important and key part of relationship building and trust.

the good thing about is that they’re able to call us after hours when they need things as well. That’s big for them, because they don’t have basic law enforcement contact. When they need something specific that needs to be done related to these kids, they will call…Typically, we find the missing kids if they’re involved in exploitation, which they know that, so they’ll call us and tell us hey, this particular kid is missing. They’re probably involved in exploitation. What do you suggest we do? Are you able to go look for them? This is what we have set up if you find them.

3.2.4. Collaboration between the Juvenile Court and the Children’s Division

So, when we make a hotline call, after they do their investigation, then yeah, they will call us back and tell us what’s going on usually. Especially if we have an active case in the unit. Usually. But in terms of collaborating an investigation- they do their own thing once they get this information. Right? And I do have a current case in the unit where initially the children’s division investigator talked to me but they haven’t talked to me since then about anything.

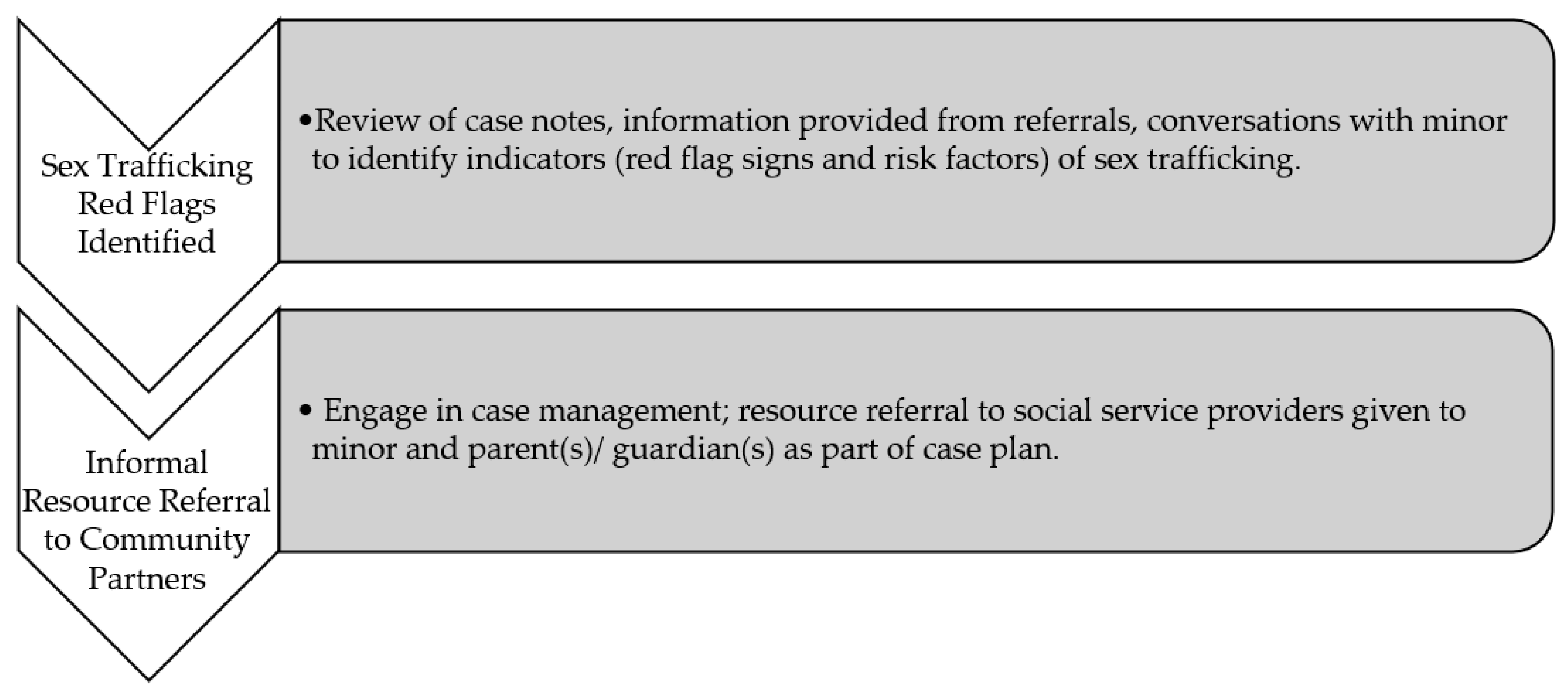

3.3. Processes Used in Study Site B

Yeah, I do. I think we all need to be informed, because I think we sometimes think in categories, like we have the sex-offender unit, we’ve got the informal unit, we’ve got the investigative unit. I think that if we, in general, all are aware and it’s a protocol for everyone, not just a particular unit, that would be very helpful.

3.3.1. Collaboration between Social Services and the Juvenile Courts

With [Study Site B], it hasn’t been as intentional from the administrative level, but we’ve had some really good luck with DJOs. So we have like 3 or 4 DJOs that I think are really intentional about looking for it [sex trafficking] and having us come in…

… we’ve had really good experiences, but it’s been very specific DJOs. But it’s the DJOs who are seeking it out, not because they have some kind of process. And if I look at my [Study Site B] girls, they’re coming to us predominantly through three DJOs. Okay. So it’s usually like -and those DJOs they have my cell number. We may talk on the weekends because they’re trying to figure out what’s best services for their kids, but it’s usually those specific three DJOs so to speak.

Well first of all, I discovered them quite a while ago and asked them to come and speak to our group and our unit during a unit meeting so we could get information about who they are. So, that collaboration right there is a good one because they’re willing to share information about who they are and what services they offer. In regards to my youth and other people’s, as DJOs that are… have been in [Organization] and used their service, they’re very prompt on letting you know what the youth, and the family, and the admission, and how they’re doing.

3.3.2. Collaboration between Social Service Providers and Judges

The difference for me is I’ve also had interactions with their [Study Site A] judges and their commissioner, so it’s pretty universal in the sense of like I couldn’t say the same thing about [Study Site B]. Like I couldn’t— Like I know who the judges are, but I never had like meetings and conferences with them so to speak. Even some of the, like I said, at the administrative level, we know who each other—we’ve been introduced to each other. But I don’t necessarily work with them as closely as—Violet and Helen [court administrators in Study Site A]…

3.3.3. Collaboration between the Juvenile Court and Investigators

Well, it can kind of be a pain. We kind of look forward to when they [minors experiencing sex trafficking] get assigned to a facility out of the DJO system because it’s easier to have access to them than it is sometimes with the DJOs, and that sometimes can allow their attorneys, which… Even when we try to talk to them as victims, not as a suspect of any crime, their attorneys often tell them, “Don’t say a word to the police ever about anything,” which then stops us from being able to help them as a victim, if that makes sense.

Well, we had several occasions where we had notified -Through whatever means, we had notified that there is a young girl over at the juvenile building that is there that they believe is a trafficking victim, so we’ll say, “Okay, we want to go talk to them.” And then we’ll come over to talk to them as a victim, but they say, “Well, we gotta talk to their attorney first.” And then, of course, their attorneys will say, “Don’t say a word.”

I have had contact with [Study Site A detective] and [Study Site B police investigator] in regards to this particular youth. I don’t look at anything as being any obstacles with them. …it’s always been cooperative. I mean, it really has been with them as far as dealing with the situation. They do what they can and we do what we can. [Interviewer: What makes those relationships seem cooperative?] The communication. We communicate well and we’re all on the same page. It’s the concern, I think, for the youth.

3.3.4. Collaboration with Social Service Providers and Investigators

I think that we-and I’m speaking about this point of contact, she and I are on the same page as far as wanting to be able to get a particular victim into a stable home… But I think that because we understand what is best for this victim and what’s not, because we talk about it, we can relate to each other, and work towards this goal.

3.3.5. Collaboration between the Juvenile Court and Children’s Division

It wasn’t encouraged. That’s the problem, too. The management in CPS does not encourage DJOs and CPS to go to family support team meetings. That’s where you learn everything. That’s where you learn about who their supports are, what’s happening, what’s not happening.

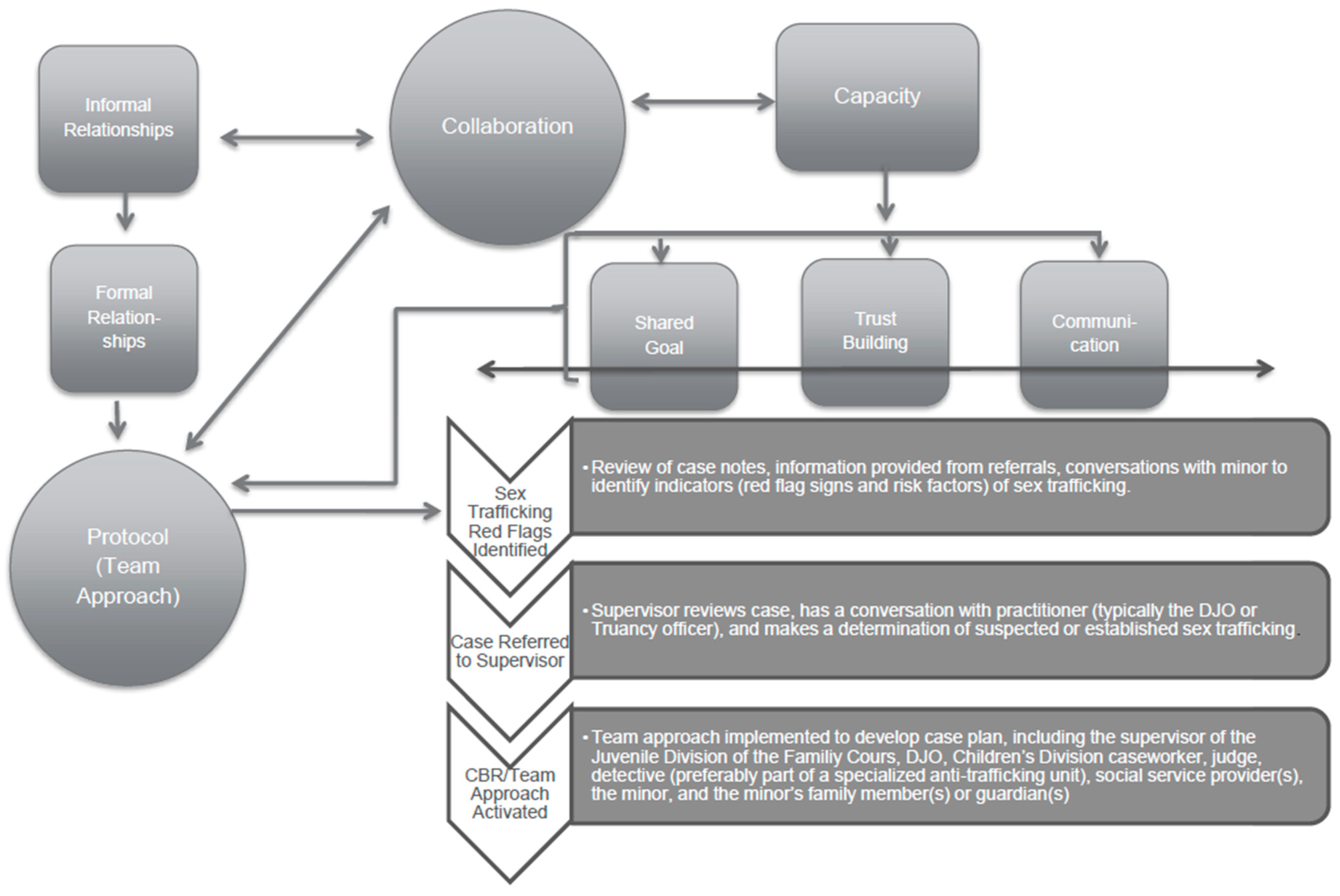

4. Discussion

5. Implications

5.1. Team Approach

5.2. Shared Goals and Trust Building

5.3. Communication

5.4. Conceptual Model

6. Limitations

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | DMST (domestic minor sex trafficking) is the term often used to describe sex trafficking of minors, however, the authors prefer MST (minor sex trafficking) to include survivors who are trafficked internationally. |

References

- Shepard, M.; Pence, E. Coordinating Community Responses to Domestic Violence: Lessons from Duluth and Beyond; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman, L.A.; Epstein, D. Listening to Battered Women: A Survivor Centered Approach to Advocacy, Mental Health, and Justice; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Zweig, J.; Burt, M. Predicting case outcomes and women’s perceptions of the legal system’s response to domestic violence and sexual assault: Does interaction between community agencies matter? Crim. Justice Policy Rev. 2006, 17, 202–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, N.E.; Bybee, D.I.; Sullivan, C.M. Battered women’s multitude of needs: Evidence supporting the need for comprehensive advocacy. Violence Against Women 2004, 10, 1015–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boxill, N.A.; Richardson, D.J. Ending sex trafficking of children in Atlanta. Affilia 2007, 3, 138–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greeson, M.; Campbell, R. Sexual assault response teams (SARTs): An empirical review of their effectiveness and challenges to successful implementation. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2013, 14, 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerassi, L.; Nichols, A.J. Sex Trafficking and Commercial Sexual Exploitation: Prevention, Advocacy and Trauma-Informed Practice; Springer Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Foot, K. Collaborating against Human Trafficking: Cross Sector Challenges and Practices; Rowman and Littlefield Publishers: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kaye, J.; Winterdyk, J.; Quarterman, L. Beyond criminal justice: A case study of responding to human trafficking. Can. J. Criminol. Crim. Justice 2014, 56, 23–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeo-Oxenham, K.A.; Schneider, D.R. Partnership and the 3Ps of human trafficking: How the multi-sector collaboration contributes to effective anti-trafficking measures. Int. J. Sustain. Hum. Secur. 2015, 2, 102–116. [Google Scholar]

- Nichols, A.J.; Cox, A. A Pilot Study Comparing sex trafficking indicators exhibited by adult and minor service populations. J. Hum. Traffick. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerassi, L.; Nichols, A.J.; Cox, A.; Kimura-Goldberg, K.; Tang, C. Examining commonly reported sex trafficking indicators from practitioners’ perspectives: Findings from a pilot study. J. Interpers. Violence. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Dyke, N.; McCammon, H. Strategic alliances: Coalition Building and Social Movements; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Gerassi, L.; Nichols, A.J.; Michelson, E. Lessons learned: Benefits and challenges in community based responses to sex trafficking and commercial sexual exploitation. J. Hum. Traffick. 2017, 3, 285–302. [Google Scholar]

- Limanowska, B.; Konrad, H. Problems of Anti-Trafficking Cooperation. Strateg. Human Traffick. Role Secur. Sect. 2009, 427–458. [Google Scholar]

- Busch-Armendariz, N.B.; Nsonwu, M.; Cook Heffron, L.A. A kaleidoscope: The role of the social work practitioner and the strength of social work theories and practice in meeting the complex needs of people trafficked and the professionals that work with them. In Int. Soc. Work.; 2014; Volume 57, pp. 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nsonwu, M.; Cook Heffron, L.; Welch-Brewer, C.; Busch-Armendariz, N. Supporting Sex-Trafficking Survivors Through a Collaborative SinglePoint-of -Contact Model: Mezzo and Micro Considerations. In Social Work Practice with Survivors of Sex Trafficking and Commercial Sexual Exploitation; Nichols, A., Edmond, T., Heil, E., Eds.; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Farrell, A.; Dank, M.; de Vries, I.; Kafafian, M.; Hughes, A.; Lockwood, S. Failing victims? Challenges of the police response to human trafficking. Criminol. Public Policy 2019, 18, 649–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, T.R.; Lutze, F.E. Anti-human trafficking interagency collaboration in the stte of Michigan. An exploratory study. J. Hum. Traffick. 2016, 2, 156–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bintliff, A.; DiPrete Brown, L.; Vollinger, L.; Alonso, A.; Geran, J. Policies and Services for Survivors of Sex Trafficking: A Report of the 4W STREETS of Hope Fora at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, July 2015–September 2018; (UNESCO Working Paper Series 004-04-2020); 4W Initiative; University of Wisconsin-Madison: Madison, WI, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Gerassi, L.; Nichols, A.J. Heterogeneous perspectives in coalitions and community based responses to sex trafficking asn commercial sex. J. Soc. Serv. Res. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litam, S.D.A.; Lam, T.C. Sex trafficking beliefs in counselors: Establishing the need for human trafficking training in counselor education programs. Int. J. Adv. Couns. 2020, 34, 234–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litam, S.D.A. Child sex trafficking: Strategies for identification, counseling and advocacy. Int. J. Adv. Counseling. 2021, 43, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratts, M.J.; Singh, A.A.; Nassar-McMillan, S.; Butler, S.K.; McCullough, J.R. Multicultural and Social Justice Counseling Competencies. 2015. Available online: https://www.counseling.org/docs/default-source/competencies/multicultural-and-social-justice-counseling-competencies.pdf?sfvrsn=20 (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- Andretta, J.; Woodland, M.; Watkins, K.; Barnes, M. Towards the discreet identification of commercial sexual exploitation of children (CSEC) victims and individualized interventions: Science to practice. Psychol. Public Policy Law 2016, 22, 260–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bath, E.P.; Godoy, S.M.; Morris, T.C.; Hammond, I.; Mondal, S.; Goitom, S.; Farabee, D.; Barnert, E.S. A specialty court for U. S. youth impacted by commercial sexual exploitation. Child Abus. Negl. 2020, 100, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Gies, S.; Healy, E.B.; Bobnis, A.; Cohen, M.; Malamud, M. Changing the Legal Response to Minors Involved in Commercial Sex, Phase 2. The Quantitative Analysis. Office of Justice Programs’ National Criminal Justice Reference Service. 2019. Available online: https://www.ojp.gov/pdffiles1/ojjdp/grants/253225.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- Green, B.; Gies, S.; Bonis, A.; Healy, E.B. Safe Harbor Laws: Changing the Legal Response to Minors Involved in Commercial Sex, Phase 3. The Qualitative Analysis. Office of Justice Programs’ National Criminal Justice Reference Service. 2019. Available online: https://www.ojp.gov/pdffiles1/ojjdp/grants/253244.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- Hershberger, A.; Sanders, J.; Chick, C.; Jessup, M.; Hanlin, H.; Cyders, M. Predicting running away in girls who are victims of commercial sexual exploitation. Child Abus. Negl. 2018, 79, 269–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liles, B.; Blacker, D.; Landini, J.; Urquiza, A. A California multidisciplinary juvenile court: Serving sexually exploited and at-risk youth. Behav. Sci. Law 2016, 34, 234–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morash, M. The nature of co-occurring exposure to violence and of court responses to girls in the juvenile justice system. Violence Against Women 2016, 22, 923–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, J. Sometimes somebody just needs somebody, anybody- to care: The power of interpersonal relationships in the lives of domestic minor sex trafficking survivors. Child Abus. Negl. 2018, 81, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprang, G.; Cole, J.; Leistner, C.; Ascienzo, S. The impact of Safe Harbor legislations on court proceedings involving sex trafficked youth: A qualitative investigation of judicial perspectives. Fam. Court. Rev. 2020, 58, 816–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aussems, K.; Muntinga, M.; Addink, A.; Dedding, C. “Call us by our name”: Quality of care and wellbeing from the perspective of girls in residential care facilities who are commercially and sexually exploited by “loverboys”. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 116, 105213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macy, R.J.; Johns, N. Aftercare services for international sex trafficking survivors: Informing U.S. service and program development in an emerging practice area. Trauma Violence Abus. 2011, 12, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preble, K.M.; Nichols, A.J.; Cox, A. Working with survivors of human trafficking: Results from a needs assessment in a Midwestern state. Public Health Rep. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preble, K.M.; Tlapek, S.M.; Koegler, E. Sex trafficking knowledge and training: Implications from environmental scanning in the Midwest. Violence Vict. 2020, 3, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vollinger, L.; Campbell, R. Youth service provision and coordination among members of a regional human trafficking task force. J. Interpers. Violence 2020, 37, NP5669–NP5692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reed, L.; Sharkey, J.; Wroblewski, A. Elevating the voices of girls in custody for improved treatment and systemic change in the juvenile justice system. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2021, 67, 50–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nichols, A.J.; Gerassi, L.B.; Gilbert, K.; Taylor, E. Provider Challenges in Responding to Retrafficking of Juvenile Justice-Involved Domestic Minor Sex Trafficking Survivors. Child Abus. Neglect. 2022, 126, 105521. [Google Scholar]

- Littlejohn, S.W. Theories of Communication; Wadsworth/Thomson Learning: Belmont, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Infante, D.A.; Rancer, A.S.; Womack, D.F. Building Communication Theory; Waveland Press: Prospect Heights, IL, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin, J.; Strauss, A. Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, B.G.; Strauss, A. The Discovery of Grounded Theory; Aldine Publishing: Chicago, IL, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Spradley, J. The Ethnographic Interview; Harcourt, Brace, Janovich: San Diego, CA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, T. Perceptions of the benefits and barriers to anti-human trafficking interagency collaboration: An exploratory factor analysis study. Societies 2023, 13, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preble, K.M.; Nichols, A.J.; Owens, M. Assets and logic: Proposing an evidence-based strategic partnership model for anti-trafficking response. J. Hum. Traffick. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study Site A (n = 13) | Study Site B (n = 9) | Study Site A and B (n = 13) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participant | Job Title | Participant | Job Title | Participant | Job Title |

| Taryn | Investigator | Dominick | Investigator | Janet | Therapist/Director, Children’s Services |

| Kevin | Investigator | Peter | Investigator | Debbie | Therapist, Children’s Services |

| T’Asia | Shelter staff | Phil | Investigator | Anita | Therapist/Coordinator of Prevention Education Groups |

| Bruce | Truancy Officer | Griffin | Investigator | Chloe | Program Director |

| David | Truancy Officer | Carla | DJO | Clover | Therapist, Residential and Outpatient, sex trafficking specific |

| Sophie | DJO | Candy | DJO | Lynda | Director, Youth Shelter |

| Henry | DJO | Diane | DJO | Dorothy | Therapist, Youth Shelter |

| Elliot | DJO | Leslie | DJO | Jenna | Case Manager, Youth Shelter |

| Shirley | DJO | Ruby | DJO | Amelia | Case Manager, Children’s Services |

| Cassandra | DJO | Madonna | Director, Case Manager, Youth Drop-In Center | ||

| Shileah | DJO | Kristi | Program director, Youth Shelter | ||

| Thalia | DJO | Tessa | Case manager | ||

| Tina | DJO | Nora | Drop-In Center |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nichols, A.; Slutsker, S.; Oberstaedt, M.; Gilbert, K. Team Approaches to Addressing Sex Trafficking of Minors: Promising Practices for a Collaborative Model. Societies 2023, 13, 66. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc13030066

Nichols A, Slutsker S, Oberstaedt M, Gilbert K. Team Approaches to Addressing Sex Trafficking of Minors: Promising Practices for a Collaborative Model. Societies. 2023; 13(3):66. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc13030066

Chicago/Turabian StyleNichols, Andrea, Sarah Slutsker, Melissa Oberstaedt, and Kourtney Gilbert. 2023. "Team Approaches to Addressing Sex Trafficking of Minors: Promising Practices for a Collaborative Model" Societies 13, no. 3: 66. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc13030066

APA StyleNichols, A., Slutsker, S., Oberstaedt, M., & Gilbert, K. (2023). Team Approaches to Addressing Sex Trafficking of Minors: Promising Practices for a Collaborative Model. Societies, 13(3), 66. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc13030066