Abstract

The levels of adherence to results in the implementation of public policies within educational communities can vary greatly depending on several factors: program coverage, funding level, the level of understanding of program goals, the duration of implementation, and the dissemination of results. In today’s digital society, the most relevant factor is precisely the communication of results, even when the way in which these are reached is overlooked. As a result, non-causal, high-impact relationships are installed in the collective consciousness. This article presents the results of a study that aims to measure the level of impact of the implementation of a public policy developed over two years in educational establishments in the Los Ríos Region of Chile, and it looks into the level of adherence to results three years after its implementation. The results explain that the differentiating factor is the type of dissemination of results, in direct correlation to the digital media used and the digital culture of the establishment, which allows to previously project the conditions of possibility for a type of adherence, even though we need larger scale measurements to determine with certainty this point of causality.

1. Introduction

When establishing public policies, one of the most relevant factors is the level of dissemination and coherence that this policy might have in terms of the entity with which it is associated. Specifically, educational establishments are frequently summoned by diverse proposals that do not necessarily flow harmoniously, but rather are generated by diverse sources, where the school is the center of application and the implementation of educational, social and economic policies, external educational programs, national and international research, and others.

This makes the school, as the center of knowledge and dissemination, a space that is in constant demand to respond to diverse requirements, passing from one program to another without any real impact on the development of basic skills for the students in the establishment. On the other hand, often the public policies and programs to be implemented in an educational context arise in disconnection from the Institutional Educational Projects (IEP), which leads to a dispersion and incoherence between the establishment’s actual declaration (IEP) and what is required for execution (educational actions that arise from external interventions), with no analysis of the feasibility of incorporating policy elements into identity spaces.

This displaces the analysis of the effectiveness of the implementation of certain public policies in education to the level of achievement and fulfillment of the previously determined milestones. It establishes a sense of coherence between what the program originally proposes and what is finally executed, delimiting the analysis to factors such as development level, execution level, and achievement level, all in a self-recursive analysis that does not necessarily end up affecting the school, since it does not arise from the identity or the needs of the school.

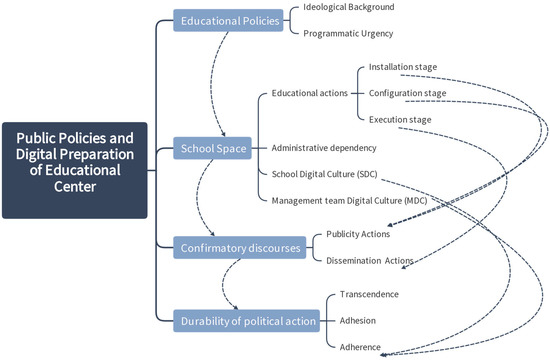

In this study, we set forth to analyze the level of impact of public policies in educational establishments from the perspective of the adherence shown in daily discourse and in the identity factors of the school where programs dependent on public policies are being carried out. Factors considered include essential elements such as the digital culture of the establishment, the culture or cultural heritage of its governance team (management), and the dissemination elements originally selected upon establishing or applying to any given intervention process.

2. Implementation and Adherence to Educational Policies

The public policy implementation processes in education goes through several stages, from their creation, usually outside educational spaces, to their implementation, which should generate strategies for their adoption in educational spaces that do not interfere with the traditional activities of the school. The consequence of this process is that an educational policy of great benevolence for the school, such as a digital literacy policy (Yo elijo mi PC), or a non-discrimination policy (school coexistence plan), is usually included in the daily activities of the establishment without necessarily having an effective and measurable impact on daily life.

This means that the public policy implementation process in full deployment does not necessarily mean a transformation of educational practices on any of its multiple levels, but often ends up reduced to a specific activity, with a momentary, usable, and benevolent impact, but not a long-term one, as it is understood that the space occupied/vacated by a type of action associated with an implementation program will end up being occupied/vacated by another program once the first one ends.

This leads to a questioning of the true level of impact of the various programs that depend on specific educational policies, since each seems to occupy a momentary and always temporary place among the school’s activities.

2.1. Public Policy Concept

When we talk about public policies, we are referring to “a set of interrelated options and decisions that implies the establishment of goals and the definition of the means to achieve them, in response to policy demands” [1] (p. 4) which, at the same time, can be developed as the decision to intervene or not intervene in certain aspects, given that any decision that is influenced by the government towards a certain phenomenon becomes policy execution [2,3]. Under this conceptualization, a policy has its origin in a set of decisions that do not necessarily consider the space in which it is carried out as the determining phenomenon. Rather, it consider the interaction space as a space that makes the execution of a policy possible or not, given that the phenomena, requirements, and needs are not always in place in all possible spaces, but are traditionally in the greatest number of them.

This explains why a policy contemplated in an educational context is a highly variable type of intervention, since it depends on factors that are not necessarily lasting, such as the general lines of a given government, the ideological vision underlying those in power, or the contingencies that motivate power groups. All these factors, which are dependent on factors temporarily in power, without necessarily being factors dependent on hegemonic groups, are at the same time dependent on circumstantial factors in their manifestation [4].

Therefore, a temporary need, confirmed by a certain ideological vision supported by the group or groups in power, gives rise to a policy that aims to resolve this need, facilitating the evaluation of the equation “need met = need resolved”, which is not necessarily consistent with the reality of the school. In their execution, policies often end up as a process, evaluating the levels of execution and coherence with the need identified, but not necessarily evaluating their durability over time. Exceptionally, when a policy has high penetration into the public discourse and the collective image, it can become a law with the intention of ensuring its durability over time.

In the specific case of Chile, educational public policies implemented in the post-dictatorship process have been numerous. They have mainly depended on contingencies and have been evaluated by specific governments. A policy implemented during the first post-dictatorship government of Patricio Aylwin (1990–1994), as was the implementation of quality and equity improvement programs (P900, MECE Program), despite the importance of its execution, no longer makes sense after 2003, when other policies of greater interest emerged (such as the Montegrande program). Additionally, the focus disappeared over time or the policies were absorbed by other actions, such as the division of actions into various policies and laws.

2.2. Adherence to Associated Discourses

The concept of adherence is used in the social sciences to refer to the adoption of a certain set of concepts, of certain epistemic fields, whose incorporation into the general discourse occurs spontaneously as a confirmation of the acceptance of a global discourse that permeates other specific comprehensions. In the educational realm, we can find references in the field of mathematical school discourse [5,6,7], understood in this setting as the adoption of a discourse built for a region of knowledge that is adopted until it becomes a dominant generic comprehension [5]. In this sense, the phenomenon of adherence is the phenomenon that justifies the adoption of certain ways of comprehending a given phenomenon in the application of general phenomena.

On the other hand, the concept of adherence is understood in health sciences as the adherence, adoption and permanence of certain treatments, whether pharmacological or other, in a notion closer to the concept of loyalty in action and acceptance of a supporting discourse, thereby giving it a positive meaning [8]. In this sense, the concept of adherence refers to the acceptance of the guiding discourse and its indications, placing it in line with the expected consequence.

In this research, we will adopt a concept of adherence that is closer to the second meaning, assuming adherence as acceptance, adoption, and permanence in the discourse of certain structures that justify the benevolence of the intervention model proposed by a given policy. In this sense, we will standardize the presence of a problem that gives rise to a public policy aimed at a solution with the presence of a health disorder that requires the intervention of certain treatments, whose permanence and acceptance of the associated discourse (adherence) makes it possible to restore the state of wellness.

2.3. The School as a Space for Policy Execution

The set of public policies in education, then, takes the school as its privileged space for execution, even when education is a multiple, major, and complex phenomenon in the set of spaces for action. The observable levels of implementation of the proposed public policies progress from macro-policies, from formulation and analysis, meso-policies, through management and negotiation, being the micro-policies the ones that see the school as a space of interaction and execution, finally being there where the proposal is implemented as such.

Education as a right that is officially provided, sanctioned, and administered by the State is deployed from the higher to lower levels, covering each and every actor, albeit somewhat subject to the ideological consideration of the whole. For example, if the educational policy in execution is a policy that considers identity factors and the execution of pedagogical action as relevant to the development of a pedagogical process, it is natural that this policy is not directed exclusively toward the school space as the only space where it can be executed, but also that it permeates all levels. In the particular case of Chile, this policy permeates the specifically micro levels referring to the school classroom (Sistema de Evaluación del Desempeño Profesional Docente, or Professional Teacher Performance Evaluation System), the authorization for the exercise of pedagogy (General Education Law, Decree 352/2003), to the meso-levels referring to the teacher training process, both for those in practice (Teacher Professional Development System) and those in the training process (Standards for Initial Teacher Training), and even for those who are in the process of verifying pedagogical skills (Framework for Good Teaching). On a macro level, this same element may affect all levels, from election and nomination practices for members of the National Education Council (most of whom are teacher trainers or teachers with proven academic experience, as stipulated in Decree 70/2010) to the nomination of an Education Minister with an educational background in teaching. We can thereby exemplify that the implementation of a policy can indeed affect the entire educational system, even when it is understood, and tends to identify the school as its absolute space for implementation.

However, the implementation of short-range policies, with little capacity to permeate the entire educational system, that affect only the micro level known as school space, continues to be the keynote of the implementation of educational policies. Considering that policies are deployed to address a specific problem or aspect, and that many times the choice regarding which problematic element of the school system takes precedence over others is based on an ideologically permeated perception, more sensationalist policies are often favored over effective ones, establishing doubts regarding the effectiveness, relevance, and prevalence of the applied policy. The report entitled “Balance de la política Educacional 2018–2021”regarding the implementation in education during the Government of Sebastián Piñera Echeñique [9] analyzes the actions implemented throughout the period of government, highlighting two main aspects: the low level of compliance with the policies promised in the educational context (only 22% of the total); and the minimal intervention of the government program in structural factors, focusing primarily on actions to strengthen the economy and impact the classroom (reinforce the educational market system). Of the percentage actually executed, only one specific policy is considered to refer to meso-structural levels (“Design and implement the quality assurance system at a pre-school level”), while the rest refer to the micro level (immediate impact in the classroom). This poses the challenge of understanding how a real and lasting level of impact can be established given the scant connection with structural levels that can give it support and durability.

For this, we must allude to the penetration of digital broadcast media in the collective discourse, considering that the prevalence of a digital medium over a traditional one is much higher among social media users, who are, indeed, the people who make up the school community. It is known that digital communication as a dissemination strategy has been imposed both positively and negatively in recent years. Positively through the installation of high-impact ideas and perspectives with low cost and the possibility of long-term adhesion, and negatively through the indiscriminate dissemination of fake news, a phenomenon associated with populist political campaigns over the last 5 years, notably the presidential campaigns of Trump in the United States, Kast in Chile, and Bolsonaro in Brazil, and the disinformation campaign around the rejection vote in the process of generating a new Constitution in Chile [10,11,12,13,14].

In this study, we will analyze the level of adherence to a particular educational policy, whose origin is not necessarily in education as a recursive field but rather accesses education and the school space as an intervention proposal for the fulfillment of certain purposes. We refer to the policy known as Plan Against Childhood Obesity Junaeb-CONTRAPESO, which is part of a set of intersectoral policies (Health Ministry, Sports Ministry, Social Development Ministry) that seek to counteract the overweight and obesity pandemic [15].

2.4. Entertaining Breaks

The Policy Against Childhood Obesity was enacted in 2016, considering 50 measures to be executed by JUNAEB, the National Board of School Aid and Scholarships, to adequately address this disease resulting from excessive malnutrition [16]. It is grounded in the objective fact that obesity has become a worldwide problem, whose prevalence rate increases considerably each year [17,18]. In fact, in the 2021 nutritional map, total overweight levels reach 27.3% of the entire school population studied, while obesity reaches 31% for school ages [19]. This data is especially worrisome because it exceeds 47% in the younger years (pre-kindergarten, kindergarten, and first grade).

The country developed a proposal to address this growing problem, specifically an intervention action focused on schools, which was tendered through a public tender through JUNAEB, called “Recreos Entretenidos 2018–2019” (“Entertaining Breaks 2018–2019”) [20], involving the implementation of recreational actions in various municipal and/or subsidized educational establishments for two years. The intervention was executed in five schools in the municipality of Valdivia: Escuela Chile, Escuela Mexico, Escuela Fernando Santiván, Escuela El Bosque, and Escuela Teniente Merino [21], covering a population of 3200 students. These were selected based on the priority given by the Regional Directorate of JUNAEB.

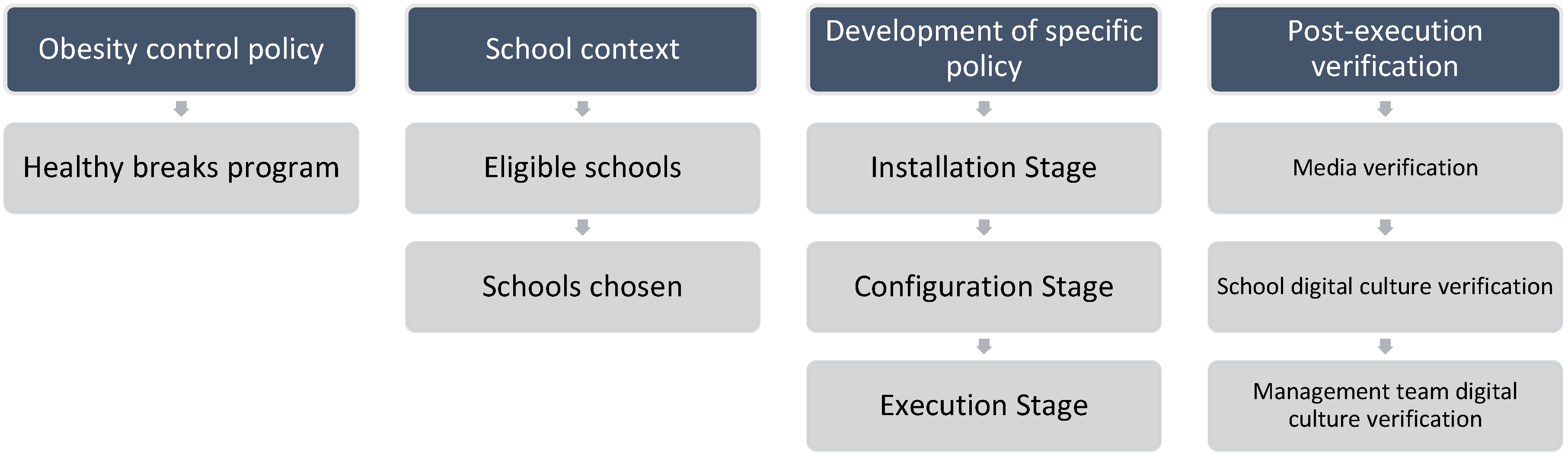

During the stipulated period (2018 and 2019), a process was implemented in each establishment that involved three stages of execution:

- Installation Stage (IS): This stage involved the implementation of actions with greater participation from the management teams of each establishment, as well as a familiarity of the context of each space. This mainly involved the implementation of recreational sessions during school recess, actions aimed at generating spaces of coexistence, companionship and acceptance through methodology that is clearly differentiated from the classroom space [22]. The final milestone of this stage was a competition for the creation of the program logo in the municipality of Valdivia with the participation of designs from all the schools.

- Team Configuration Stage (CS): This stage involved actions directed at identifying leaders in the student community and generating several instances to train them so that they could participate more actively with this implementation of entertaining breaks, supporting the work carried out by the monitors. It also incorporated actions aimed at making the program extensive to everyone, encouraging greater student participation. The final milestone of this stage was an event for teachers or parents, with a proposal of themes to be addressed in a workshop related to each segment.

- Execution Stage (ES): The third stage corresponded to the implementation of final activities to promote healthy lifestyles, combined with sessions during recess with an emphasis on monitoring the activities set up by student leaders. Along with this, to give the school autonomy in the development of activities, different playful figures were painted: “Luche”, “Gato”, “Twister”, and “Cuncuna”, for example, along with blackboards on the walls available to draw on with chalk during recess and classes.

Throughout the period considered, although most activities could be carried out, there were several variations (as is typical in all school dynamics) that required the adaptation of activities: programmatic changes in the school (during both years), teacher strike (2018), social unrest (2019), and the imminent closure of the establishments (end of 2019). Added to this was the late start of the project implementation, despite the efforts made on a management level, negatively affecting the information collection stage (IS) and the monitor preparation stage (CS). This was compounded by the fact that the schools involved in the intervention were chosen based on the technical criteria stipulated in the bidding conditions, without their development having necessarily been linked to the execution of their Institutional Educational Project. Therefore, in the first year of execution, the implementation encountered multiple difficulties (late incorporation, lack of spaces for development, complexity in the installation due to unfamiliarity with the stages). However, from the second year, once the program became more familiar, there was greater participation and collaboration from students. Likewise, from an institutional standpoint, it was possible to establish a space for participation for students who aimed to install effective actions (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Materials and process.

3. Analysis Proposal

3.1. Implementation, Dissemination and Adherence

In light of this set of linked actions, the question that emerges relates to the level of adherence generated by the discourses associated with the process of implementing a public policy in a school community. This considered that the school, a privileged space for the implementation of public policy, is an institution with durability over time, whose significance is directly linked to the people with whom it is associated and who participate in it. What factors promote or facilitate adherence to the discourses associated with the implementation of a specific policy? To what degree do the media used, the digital culture of the establishment, and the particular digital culture of the management teams favor the installation of certain categories intended by the same policies?

More concretely, two years after the end of the public policy giving rise to the entertaining breaks program, how much of what was proposed and invested in the participating schools prevails as part of the school culture? Does the implementation of a limited public policy in relation to the daily life of the school have any level of effectiveness? Is it possible to establish a virtuous relationship between implementation, the media, school digital culture and adherence to complementary discourses?

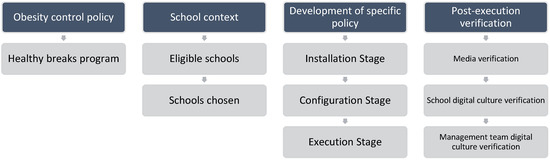

3.2. Work Methodology

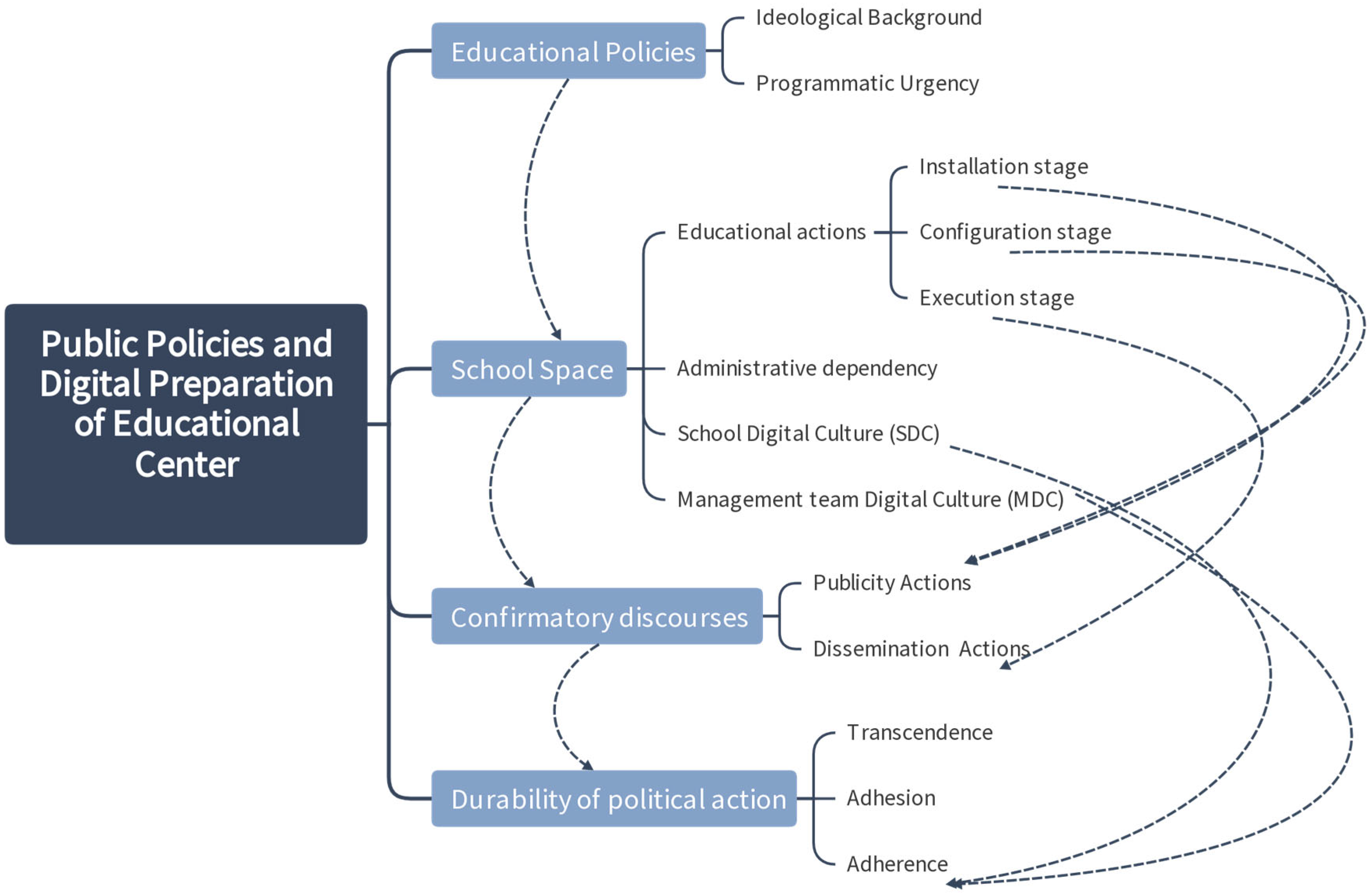

To provide an answer to these questions, this study proposes a methodology of analysis of multiple sources, in order to associate the different factors linked in the research process. A holistic understanding of the phenomenon can help to explain the interconnected elements in the research (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Interconnected elements in the execution of public policies in education. Source: author.

In order to analyze the set of interconnected elements, the materials must be organized according to their source, reliability, and readability. The process, therefore, requires a verification of the following interconnections:

- Interconnection between Dissemination Actions (DA) and Installation, Configuration and Execution Stages (IS, CS, ES).

- Interconnection between Dissemination Actions (DA) and School Digital Culture (SDC) and Management Team Digital Culture (MDC)

The result of the analysis process can be read as follows:

H0 = The adherence level is related to the interconnection between DA and SDC/MDC, deployed during IS, CS and ES.

H1 = The adherence level is not related to the interconnection between DA and SDC/MDC, deployed during IS, CS and ES.

The sources used to confirm the material to be analyzed are:

- -

- Adherence: Presence or absence of practices, language or global understandings of the policy applied through the entertaining breaks, verified in official direct sources. Institutional Educational Project updated after 2019 (IEP), Internal regulation (IR).

- -

- DA: Original project, report of results, project logbook. Materials used during 2018–2019.

- -

- IS, CS and ES: Original project, report of results, project logbook. Materials used during 2018–2019.

- -

- SDC: Technological maturity model from the center (TIC Model, Autoridad País Vasco, v. 2017). Questionnaire applied in the five educational establishments as a result of the original intervention, 2022.

- -

- MDC: DigComp Edu survey, digital version (Marco Europeo de Competencias Digitales, v. 2021). Questionnaire applied to the management teams of the five educational establishments as a result of the original intervention, on 2022.

The materials effectively collected in the study were (Table 1):

Table 1.

Materials used in research process.

The materials collection process took place between May 2022 and November 2022, which included the validation and presentation of several considerations that require the adjustment of the model:

- -

- Regarding the Management Team Digital Culture. When applying the survey to senior management teams, it was determined that most management teams had been replaced with respect to those who participated in the educational center and in these roles during the development of the program that gave rise to this research. In consideration of this, the study resolved to eliminate the Management Team Digital Culture factor from the formula, finally leaving:

Interconnection between Dissemination Actions (DA and School Digital Culture (SDC).

Modeling the adherence formula on the following formula:

Regarding total participants. Of the five participating centers, four participated actively and one explained that as a result of the effect of the pandemic on school dynamics, it chose to withdraw from the study and place all the energy of the student body and staff on the recovery of learning and internal dynamics. This left only four valid subjects participating through the end of the process. This has no effect on the validity of the analysis of the interconnections. However, since it is a census study, the lack of a subject must be considered in the analysis of the results.

With these considerations, and in light of the materials collected, the results are detailed below.

4. Results

4.1. Interconnection between Dissemination Actions (DA) and Installation, Configuration, and Execution Stages (IS, CS, ES)

The interconnection levels and indicators are stable in terms of means of dissemination, although dissemination programming is focused on the IS stage. It is worrying that the project does not contemplate the generation of digital resources for the dissemination of the activity and the implementation of public policy, but instead places all the weight of dissemination on traditional means, registering elements that are less likely to withstand time. The proposal determines the use of the following as means of dissemination (Table 2):

Table 2.

Resources used for dissemination.

Of the total resources identified as means of dissemination, only two include digital versions, minimizing the possibilities of deployment in alternative digital media. On the other hand, audiovisual records were documented through unofficial means (alternative individual Instagram accounts and those of the developers themselves), which are not directly linked to the school.

In terms of effective dissemination actions carried out in the final stages (CS and ES), the level of activity in terms of dissemination decreases noticeably, limiting the program to the generation of creative instances that have some relevant effect within the community, mainly trending towards the installation of the “Branding” concept, but where the means of dissemination is not in accordance with the notion of digital culture of the establishment nor with the digital practices projected within it.

Likewise, another notable element is that the dissemination practices contemplated and implemented (local, brochure, poster) completely lose validity in the period immediately following (school quarantine as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic), which means an immediate devaluation of traditional media in favor of digital media. In this sense, most of the actions implemented contradictorily lose any possibility of adherence as they were developed in the period immediately following a process of highly digitized teaching with an almost exclusive instructional/instrumental focus [23].

This speaks to the difficulty in establishing the possible effects of the process of implementing public policies in terms of penetration, only through digital media, since both the internal conditions (dissemination in ES, IS and CS) and external conditions (COVID-19 emergency) weaken the proposal if not available in digital media.

4.2. Interconnection between Dissemination Actions (DA and School Digital Culture (SDC)

The dissemination actions described above are prepared from the original project, without necessarily being thought, generated, or established from the understanding of the educational center’s digital culture, which may partly explain why it is not possible to understand which elements interact. When we talk about the digital culture of the educational center, we are talking about the Digital Culture Index based on Technological Maturity Model of the Center (ICT Model, Basque Country Authority, v. 2017). Valid results regarding educational centers can be analyzed in three different ways: those that refer to the teaching processes, those that refer to the administrative processes of the educational center and those that refer to the processes of communication and information of academic results.

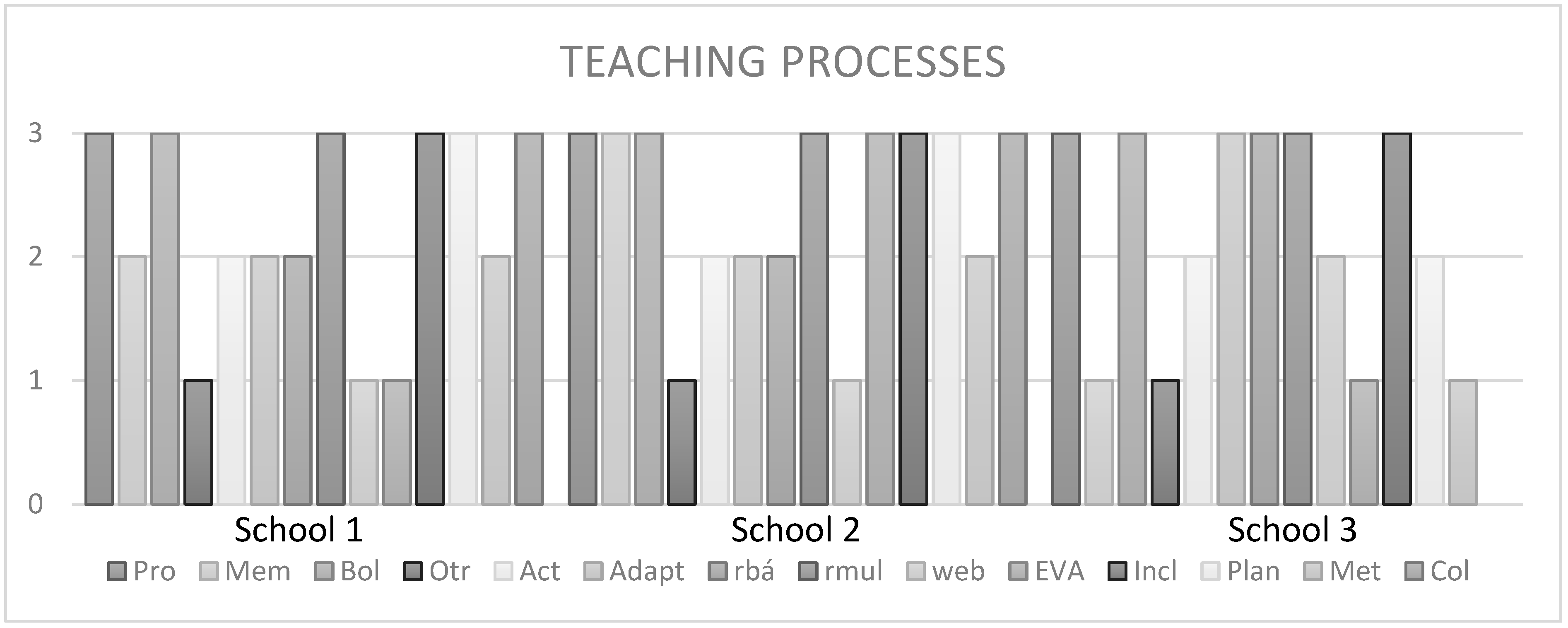

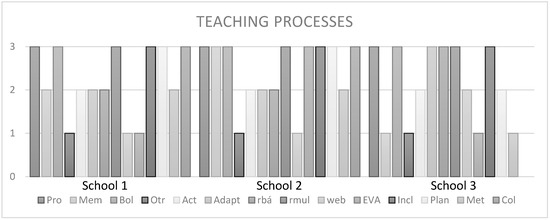

4.2.1. SDC, Teaching Processes

The Center’s Technological Maturity Model identifies three types of viable processes to analyze, where the “Teaching Processes” indicator is at the top of the list. This in turn is made up of 14 specific indicators that identify various elements in the development of teaching in the classroom instructional exercise. Although each establishment varies in its development, School 2 stands out above the rest of the sample for presenting a strategic indicator of greater scope, such as the VLE indicator (Use of Virtual Learning Environments). This indicator, which should have exploded in the teaching process during quarantine, seems to have been abandoned by the centers in general, virtuously remaining only in School 2.

However, this type of indicator (referring to teaching processes in the classroom) has no direct interference with the dissemination indicators in the IS, ES, and CS, but rather makes more reference to the development of updated teaching based on Virtual Learning Environments, which does not necessarily establish an aspect of digital penetration of a discourse, but rather the instrumental use of tools. Likewise, the indicator establishes little variation with respect to the set, establishing accumulated values of 31 (School 1), 34 (School 2) and 28 (School 3) for the establishments, with coverage of 54%, 60%, and 49%, respectively (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Teaching Processes. Source: author.

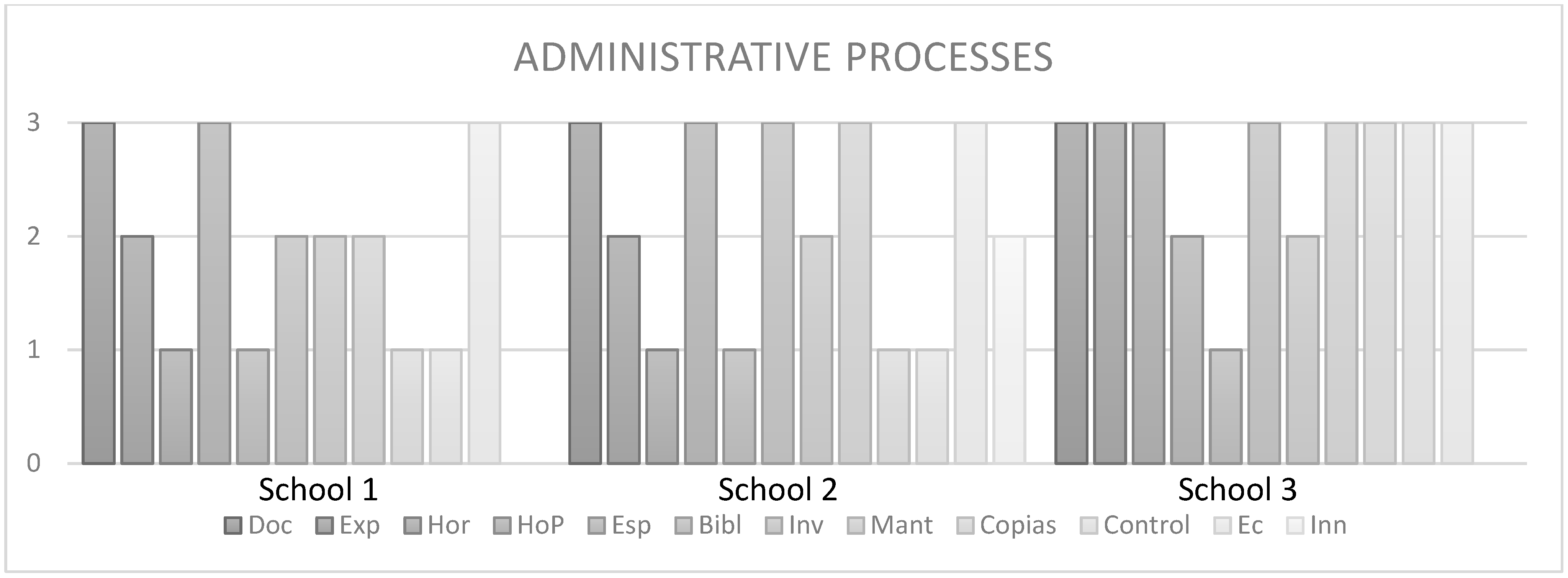

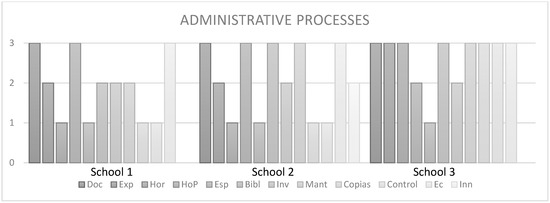

4.2.2. SDC, Administrative Processes

This indicator is relevant because it directly correlates to the materials that will be analyzed later for the presence or absence of indicator concepts in the logic of the adherence analysis. It refers to 12 indicators, of which the first five allude to the planning and organization of the educational center, the next five to elements of durability in the management of the center (assets and infrastructure), and the last ones to innovation and economic management. The educational center that ranks the highest in terms of solid indicators is School 3, scoring a total of 29 points, versus 25 for School 2 and 21 for School 1. This indicates that the school management stabilization processes (key to the configuration of a school culture) favor the conditions of School 3. When analyzed in terms of percentage of the accumulated total, School 1 presents a coverage of 58%, School 2, 69%, and School 3, 81%, which makes the level of coverage particularly noticeable (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Administrative Processes. Source: author.

Likewise, this element is much more directly linked to the concept of adherence, since these elements account for stable processes that are specific to the identity of the center and not connected to the people who manage it (as occurs with intra-classroom teaching processes), or external conditions that could play a role. In fact, from the standpoint of school management, this is the process that maintained the greatest stability even during the COVID-19 pandemic.

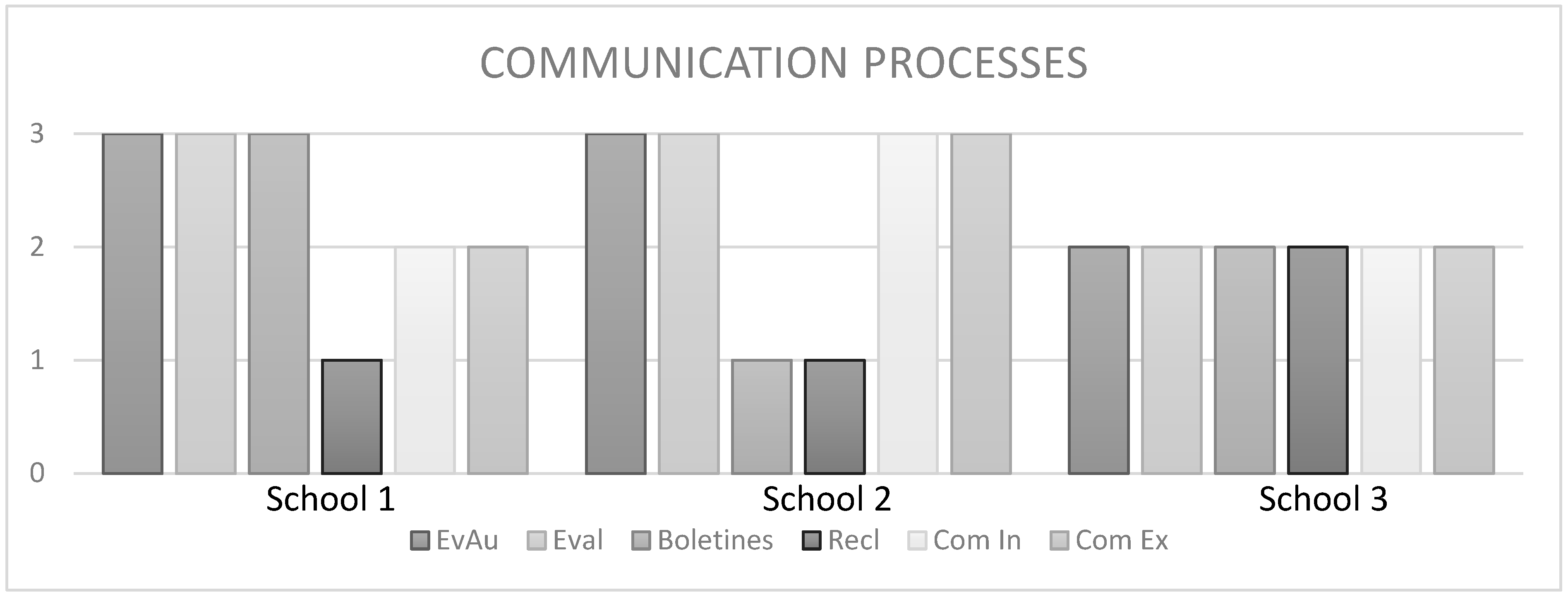

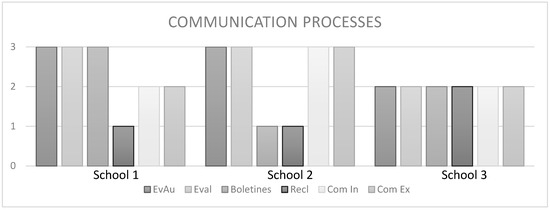

4.2.3. SDC, Communication, and Information Processes

This dimension alludes to the digitization of the communication processes of students’ academic results, in conjunction with the use of sufficient means of dissemination of global actions. In this dimension, the last two indicators of the series are especially relevant, namely, ComIn (internal communication of the center’s own actions) and ComEx (external communication of actions towards other actors), which are still being developed in Centers 1 and 3 and are at an advanced stage in School 2. However, the results of School 2 (which could allude to an ideal advanced level for the purposes of adherence levels) have the defect of presenting deficient indicators on bulletins (official communication of grades and other topics through digital resources) and Recl (presentation and management of claims against the actions of teachers or the educational center), which is not consistent with virtuous processes in the final indicators (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Communication Processes. Source: author.

In this reading, the ideal scenario for the communication processes, ComIn and ComEx, is notably low in the centers analyzed, which is also notoriously detrimental to adherence to a public discourse.

4.3. Adherence of the Discourse Associated with Public Policy

In the proposed analysis, the presence or absence of key concepts were verified as sources of review of the adherence level, considering that the review sources were created the year immediately following the public policy execution and therefore ensure its emergence from the directly related stakeholders. Key concepts arise from the study of factors that have a bearing on the foundation of the obesity control policy and the healthy break program, determining the following three key concepts and their variants:

- -

- Key Concept 1: (primary) health, (variant) healthy.

- -

- Key Concept 2: (primary) break, (variant) recreation, recess.

- -

- Key Concept 3: (primary) entertaining, (variant) entertainment.

In the analysis of key concepts in the official documents generated after the implementation of the public policy, which could subsequently provide evidence of adherence to the public policy, the relationship between the presence and absence of concepts (Table 3) is as follows:

Table 3.

Presence and absence of concepts.

The details show that School 3 maintains higher levels of adherence to the discourse on the implemented public policy, especially because the fundamental concepts of “Health” and “Healthy” appear in a more relevant range. The fact that the expression “Healthy” appears as part of the School Vision (as declared in the IEP) shows that they see themselves as such, subsequently reproducing the linked discourse in sections that mention, for example, “(teachers) further the curricular contents related to maintaining a healthy lifestyle” and “they offer healthy food in their kiosks and dining halls” (IEP School 3, p. 40), within the actions to address the personal and social development indicators. On an Internal Regulation (IR) level, the presence of the concepts of health and its variations is mentioned both in the profile of the head teacher, who “has the ability to execute and evaluate healthy lifestyle projects” (IR School 3, p. 34), in standard 7.4 of the Training Subdimension, “The management team and teachers promote healthy lifestyle habits and self-care behaviors among students” (IR School 3, p. 236), and in the set of statements related to the role of the School Food Program Officer (who reports to JUNAEB), which is not the case in the other educational centers. The actions indicated refer to structural elements of the educational center, therefore their presence is linked to the Administrative Processes dimension.

5. Conclusions: Valuation

When analyzing the available documentation and the means of verification for each of the indicators, as indicated, the educational center that presents the highest levels of adherence to the public policy is School 3, whose indicators show the constant presence of terms related to the discourses generated in the Healthy Schools program. The educational center that is closest in adherence (School 1) presents low levels of evidence, relegating evidence on adherence to a single presence (the conceptualization of “safe recess”). School 2 shows no level of evidence of adherence.

However, in relation to the evidence of a link between the level of adherence and the school’s digital culture, there is a direct link between a high level of adherence to the discourse associated with the public policy and dimension B, the “administrative processes” of the Technological Maturity Model of the Center, which refers to structural processes connected to the digital maturity of the center and the use of various strategies to implement the determined actions. This is a decisive element given that the hypothesis established is that there is a direct relationship between the school’s adherence and its digital maturity.

From a communications standpoint, the effectiveness of the public policy communication processes and the level of penetration of the associated discourses, referred to here as “adherence”, is directly related to the digital culture of the school, since it explains the installation of terms after the public policy intervention through their use in official documents: the mission, profiles, and functions of the educational center with the best level of digital development.

Likewise, there is a considerable distance between the type of dissemination action used in the public policy analyzed and the type of school culture of the educational center. While the project is mainly intended for non-digital media, with a small presence in social media through individual Instagram accounts, the members of the educational center have a high level of use and understanding of the tools that were applied during the installation of the public policy.

Finally, it is worth mentioning that the number of factors that make the process of adherence to the discourses associated with a public policy impossible, allude precisely to the difficulties in trusting face-to-face analogue as the only means. Educational centers that had no digital competence prior to the COVID-19 quarantine period were forced to urgently resolve teaching methods, and establishments that developed a virtuous model of digital skills were able to overcome this crisis precisely because of the fact that the implementation of virtual teaching processes was an update of previous processes that had already been developed (structural level). Meanwhile, educational centers must deal with unforeseen factors such as enrollment mobility, suspension of classes for health reasons, the dismissal or renewal of principal teachers, the lack of spaces for the development of activities, among others.

These factors have relevance, thinking in future process of design and implementation of educational policies. The evidence recollected demonstrate the difficulties for thinking of the real structural conditions of the educational establishments, generating process for interventions and implementation from an ideal condition, ignoring the particular conditions of the school culture, especially the capacities installed due the school’s digital culture and the permanent incorporation of new actors.

In the future, ideally, large-scale analysis processes would make it possible to look at the relationship between public discourse and adherence in the context of schools with high digital culture, in order to confirm whether the same influential elements can be con-sidered for all educational policies under development, or if this only works for the specific policy examined in this article’s thinking; for example, in comparative studies or new research considering countries with similar macro-structural levels in digital culture in educational establishments, or with schools from different countries but with similar social conditions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.V.-R. and P.C.-D.; methodology, J.V.-R.; formal analysis, J.V.-R., P.C.-D. and C.Q.-F.; investigation, J.V.-R.; resources, P.C.-D.; data curation, C.Q.-F.; writing—original draft preparation, J.V.-R.; writing—review and editing, J.V.-R., P.C.-D. and C.Q.-F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1. | School 4 suspended its participation in the study as a result of the first post-COVID school year, which led them to focus their efforts exclusively on direct teaching action in the classroom. |

| 2. | School 5 participated in the research, however, it did not present the entire survey, so its results are unusable. |

| 3. | This indicator is explained below. |

References

- Aziz Dos Santos, C. Evolución e Implementación de las Políticas Educativas en Chile; Centro de Liderazgo para la Mejora Escolar: Santiago, Chile, 2018; p. 12. [Google Scholar]

- Furlong, S.; Kraft, M. Public Policy: Politics, Analysis, and Alternatives, 7th ed.; CQC Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2020; p. 546. [Google Scholar]

- Mineduc, C.D.E. Revisión de las Políticas Educativas en Chile Desde 2004 a 2016; MINEDUC: Santiago, Chile, 2017; p. 127. [Google Scholar]

- Cuevas, H.; Paredes, J.P. Democracia, Hegemonía y Nuevos Proyectos en América Latina. Una Entrevista Con Ernesto Laclau. Polis, n. 31, 2012-07-24T00:00:00+02:00 2012.ISSN 0717-6554. Available online: https://journals.openedition.org/polis/3819 (accessed on 20 December 2022).

- Gómez, K.; Silva, H.; Cordero, F.; Soto, D. Exclusión, opacidad y adherencia. Tres fenómenos del discurso matemático escolar. Acta Latinoam. Matemática Educ. 2014, 27, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Opazo Arellano, C.E.; Marcía Rodríguez, S.L.; Cordero, F. Adherencia al discurso matemático escolar: El caso de la integral definida en la formación inicial docente. Rev. Académica UCMaule 2020, 59, 24. Available online: https://revistaucmaule.ucm.cl/article/view/681 (accessed on 20 December 2022). [CrossRef]

- Silva, H. Matemática Educativa, Latinoamérica, adherencia e identidad disciplinar. Rev. Chil. Educ. Matemática 2015, 9, 7–12. Available online: https://www.sochiem.cl/documentos-rechiem/revista-rechiem-09-N1-2015.pdf (accessed on 18 December 2022).

- OMS. Adherencia a los Tratamientos a Largo Plazo: Pruebas Para la Acción; Organización Panamericana de la Salud: Geneva, Switzerland, 2004; p. 202. [Google Scholar]

- Quiero, M.; Muñoz, G. Balance de la Política Educacional 2018–2021 A un Año del fin del Gobierno de Sebastián Piñera; Fundación Chile 21: Santiago, Chile, 2021; p. 19. [Google Scholar]

- Vega Ramírez, J.F.A.; Contreras Contreras, P. Formas y núcleos de Discurso ideológico: En torno al concepto de crisis. Univ. Politécnica Sales. Ecuad. 2022, 2022, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Vega, J.; Contreras, P. Sistemas de comunicación en la gestión operativa de crisis. In Perspectivas Transdisciplinarias Sobre la Comunicación Estratégica Digital; De Santis, A., Torres, A., Eds.; McGraw Hill: Ciudad de México, Mexico, 2023; Chapter 8; pp. 89–101. [Google Scholar]

- Valenzuela, S.; Halpern, D.; Katz, J.E.; Miranda, J.P. The Paradox of Participation Versus Misinformation: Social Media, Political Engagement, and the Spread of Misinformation. Digit. Journal. 2019, 7, 802–823. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/21670811.2019.1623701?journalCode=rdij20 (accessed on 19 December 2022). [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, S.C. Filter Bubbles, Echo Chambers, and Fake News: How Social Media Conditions Individuals to Be Less Critical of Political Misinformation. Political Commun. 2021, 39, 1–22. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/10584609.2021.1910887?src=recsys (accessed on 20 December 2022). [CrossRef]

- Tsfati, Y.; Boomgaarden, H.G.; Strömbäck, J.; Vliegenthart, R.; Damstra, A.; Lindgren, E. Causes and consequences of mainstream media dissemination of fake news: Literature review and synthesis. Ann. Int. Commun. Assoc. 2020, 44, 157–173. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/23808985.2020.1759443?src=recsys (accessed on 18 December 2022). [CrossRef]

- Lira, M. Normativas, Políticas y Programas Contra la Obesidad Estudiantil en Chile; Unidad de Estudios JUNAEB: Santiago, Chile, 2022; p. 10. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein, E. Políticas Contra la Obesidad en Chile: Reconocimientos y Falencias; Congreso Nacional de Chile: Valparaíso, Chile, 2019; p. 23. [Google Scholar]

- Mead, E.; Brown, T.; Rees, K.; Azevedo, L.B.; Whittaker, V.; Jones, D.; Ells, L.J. Diet, physical activity and behavioural interventions for the treatment of overweight or obese children from the age of 6 to 11 years. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 6, CD012651. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28639319 (accessed on 20 December 2022). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, M.; Fleming, T.; Robinson, M.; Thomson, B.; Graetz, N.; Margono, C.; Gakidou, E. Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980–2013: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 2014, 384, 766–781, ISSN 0140-6736 (Print) 0140-6736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lira, M. Informe Mapa Nutricional 2021; JUNAEB: Santiago, Chile, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- JUNAEB. Aprueba Términos de Referencia Técnicos y Administrativos, Efectúa Llamado a Concurso Público y Constituye Comisión Evaluadora para la Presentación de Proyectos del Programa Campamentos Recreativos para Escolares, Modalidad Recreos Entretenidos, Región de Los Ríos Años 2018–2019; JUNAEB: Santiago, Chile, 2018; p. 78. [Google Scholar]

- JUNAEB. Aprueba Acta de Evaluación Técnica y Dispone Selección y Adjudicación de Proyecto para la Ejecucion del Programa Campamentos Recreativos Para Niños, Modalidad Recreos Entretenidos, Región de los Ríos, Años 2018–2019. 000163; JUNAEB: Santiago, Chile, 2018; p. 15. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez, J.L. Partieron Recreos Entretenidos en Colegio Teniente Merino—Noticias UACh. Diario Uach, 2018-09-12. 2018. Available online: https://diario.uach.cl/partieron-recreos-entretenidos-en-colegio-teniente-merino/ (accessed on 20 December 2022).

- Belmar-Rojas, C.; Fuentes-González, C.; Jiménez-Cruces, L. Chilean Education in Times of Emergency: Educating and Learning during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Saberes Educativos, v. 7, 2022-07-19. 2021. Available online: https://sabereseducativos.uchile.cl/index.php/RSED/article/view/64099 (accessed on 19 December 2022).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).