The Post-COVID-19 Era, Fourth Industrial Revolution, and New Globalization: Restructured Labor Relations and Organizational Adaptation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Prolonged Global Crisis: Where Are We Nowadays?

2.2. The Accelerated 4IR and the New Globalization

3. Discussion: Restructured Labor Relations, Institutional Innovation, and the Imperative of Organizational Adaptation

3.1. Post-COVID-19 Work Environment, Emerging Labor Inequalities, and Macro–Meso Adaptations

3.2. Toward a Post-COVID-19 Organizational Readaptation

- Organizational reinvention: according to Goss et al. [123], reinventing the organization is a journey filled with necessities and difficulties—those who ride the “roller coaster” must be prepared for a challenging process that unveils and changes the hidden decision-making assumptions and foundations. Organizations usually fail to reinvent themselves because they base their future development only on past practical experience. According to Goss et al. [123], doing the same thing repeatedly and expecting different outcomes is meaningless—an issue encountered in complacent managers who overconcentrate on the organization’s prior belief system. Against this backdrop, Goss et al. [110] argue that redesigning the organization entails engaging in thorough and methodical selfcriticism rather than responding like a frightened aristocracy that must restore previous “certainties”;

- Developing a learning organization: regardless of hierarchy or experience, all employees are accountable for finding, analyzing, and addressing practical problems, allowing the organization to ameliorate itself continuously through experimentation and relearning. According to Senge [124], humanity’s real challenge is our failure to comprehend how we should govern human systems, suggesting that we need “learning organizations” that are sensitive to change and not as bureaucratic in their internal environment. Senge [124] emphasizes that hierarchy persists even in highly networked enterprises. However, according to Senge [124], the hierarchical distribution of power in learning organizations differs significantly from that of traditional enterprises because this chain of command comprises mostly guiding concepts and ideas;

- Continuous organizational balancing: according to Duck [125], the management paradigm that is usually appropriate for day-to-day procedures is insufficient for handling change since it is analogous to a patient receiving five surgical operations simultaneously, which might result in death due to shock. Breaking down the requisite organizational transformation into smaller parts seems insufficient, as the administration must deal with the dynamics of change; the real problem is bringing innovations into the intellectual work arena primarily while simultaneously balancing all the organizational jigsaw pieces. Employees frequently do not believe in the excellent outcome of change—they tend to be skeptical of the organization’s new route, trusting organizational change only when they observe an action and related results that demonstrate the benefits of a change program. Overall, Duck [112] contends that this “art of balancing” implies that change management is a collective endeavor that all stakeholders must do;

- Correlative and evolutionary SWOT analysis: according to Vlados [120], all organizations must exploit their comparative strengths to innovate, capitalizing on opportunities that arise through time; accordingly, they must avoid the possible threats that emerge from their “correlative” and evolutionary weaknesses. There are no equivalent opportunities and threats for all socioeconomic organizations; these must be continuously reexamined in light of the specific strengths and weaknesses developed over time. From Vlados’ [120] viewpoint, the correlative SWOT means finding historically constructed comparative strengths and weaknesses that lead to potential opportunities and threats based on understanding the organization’s strategy, technology, and management foundations;

- Strategic reapproaching amid chaos: according to Kotler and Caslione [126], the world has entered an irreversible disruption, and organizations need to reapproach the mechanisms by which they assess their performance. According to these authors [126], many organizations confuse goals with means and processes with outcomes, resulting in significant inefficiencies when trying to cope with the ever-unfolding crises in the emerging era of chaos. Kotler and Caslione [113] propose establishing an integrated cycle of implementation and a framework for executing strategies that cope with “chaos” by stressing the organization’s continual restrategizing to gain an edge over rivals;

- Leadership centered on principles: according to Covey [127], as multiple defensive mechanisms resist organizational transformation, all stakeholders must be prepared to express how they think the organization acts within its external environment. The goal is to understand what constitutes the consciousness behind organizational actions, and, in this context, the principles and beliefs managers have about the strategy are less significant than the unconscious methods applied on the ground. Overarchingly, Covey [111] argues that principle-centered leaders recognize that leadership entails embracing change that necessitates uncovering and committing to the organization’s fundamental beliefs;

- Focus on RASI priorities (resilience–adaptability–sustainability–inclusiveness): in another research paper that we are working on during this period, titled “Green organizational reorientations for the new globalization”, we suggest that organizations must effectively synthesize a series of internal dimensions to deal with the new global reality. We suggest that innovational greenness can be achieved through the organization’s environmental, social, and corporate governance, aiming toward the synthesized goals of resilience, adaptability, sustainability, and inclusiveness. This green targeting seems requisite, especially considering the present-day energy transition accelerated by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. However, although the relevant literature acknowledges the significance of these organizational goals, little integration is observable [128,129]. Therefore, change management and innovation residing upon these synthesizing principles could help all socioeconomic organizations in the new globalization.

4. Conclusions and Prospects

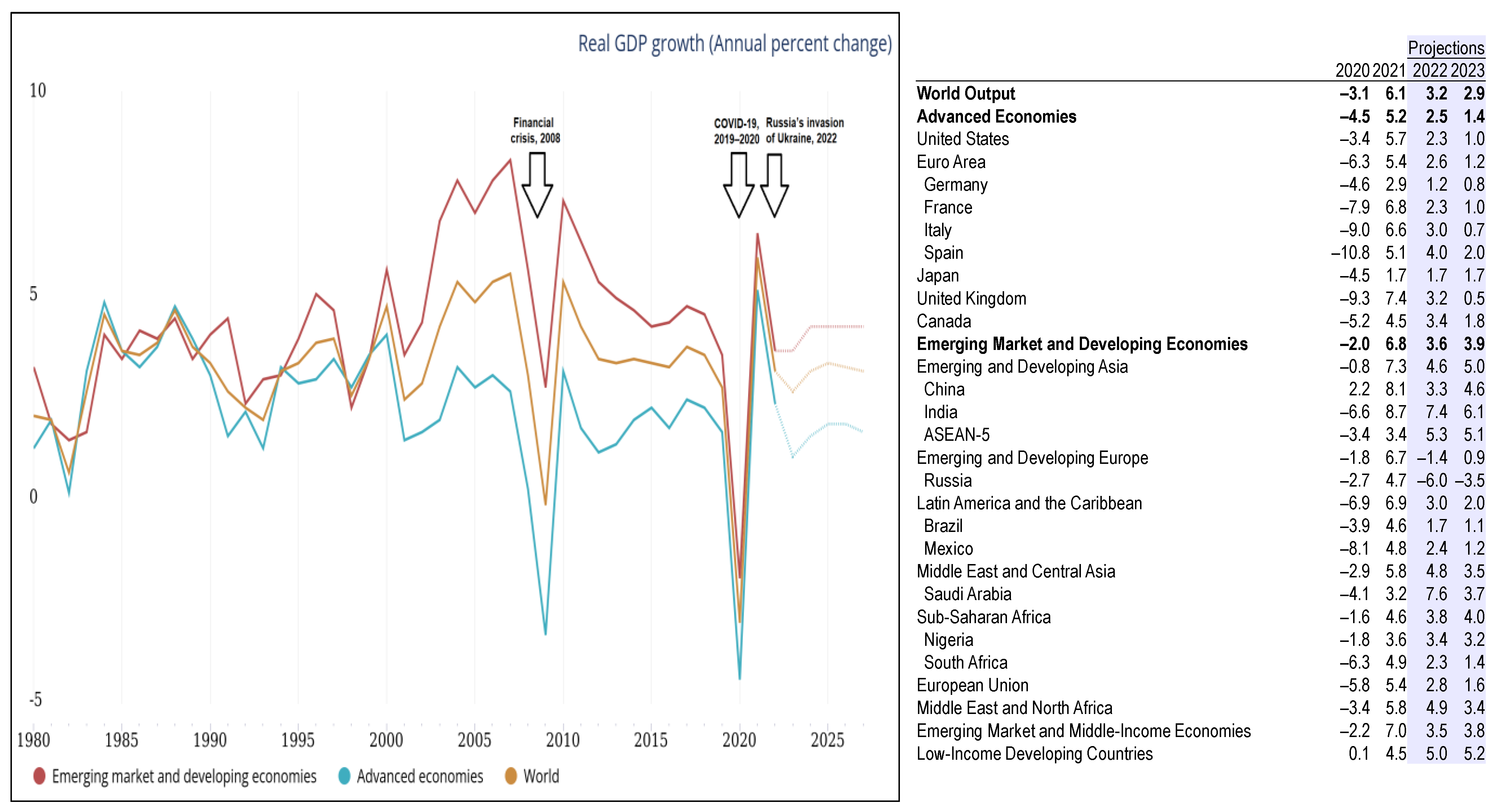

- (A)

- The COVID-19 crisis exacerbated preexisting trends, crystallizing a transition toward the 4IR. We think that an L-shaped type of global growth and development will be the definitive worldwide conclusion in the short run, expressed as persistent stagflationary pressures. The hastened energy transition sparked by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine–followed by geopolitical reevaluations across all players globally–is another significant milestone that we think belongs to the new form of globalization that is emerging nowadays. Further research seems imperative in coevolving concepts of global evolutionary transformation, such as the post-COVID-19 era, the 4IR, and the new globalization.

- (B)

- The above phenomena, in conjunction with the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, have worsened labor inequalities. Most EU countries did not adequately use social partnership procedures to plan and implement measures against COVID-19 and adjust them to the new context of the economy at the national, industry, or company level. Nonetheless, previous experience has proven that partnership and employee voice schemes can effectively confront industrial conflict and labor market inequalities, especially at the microlevel of enterprises;

- (C)

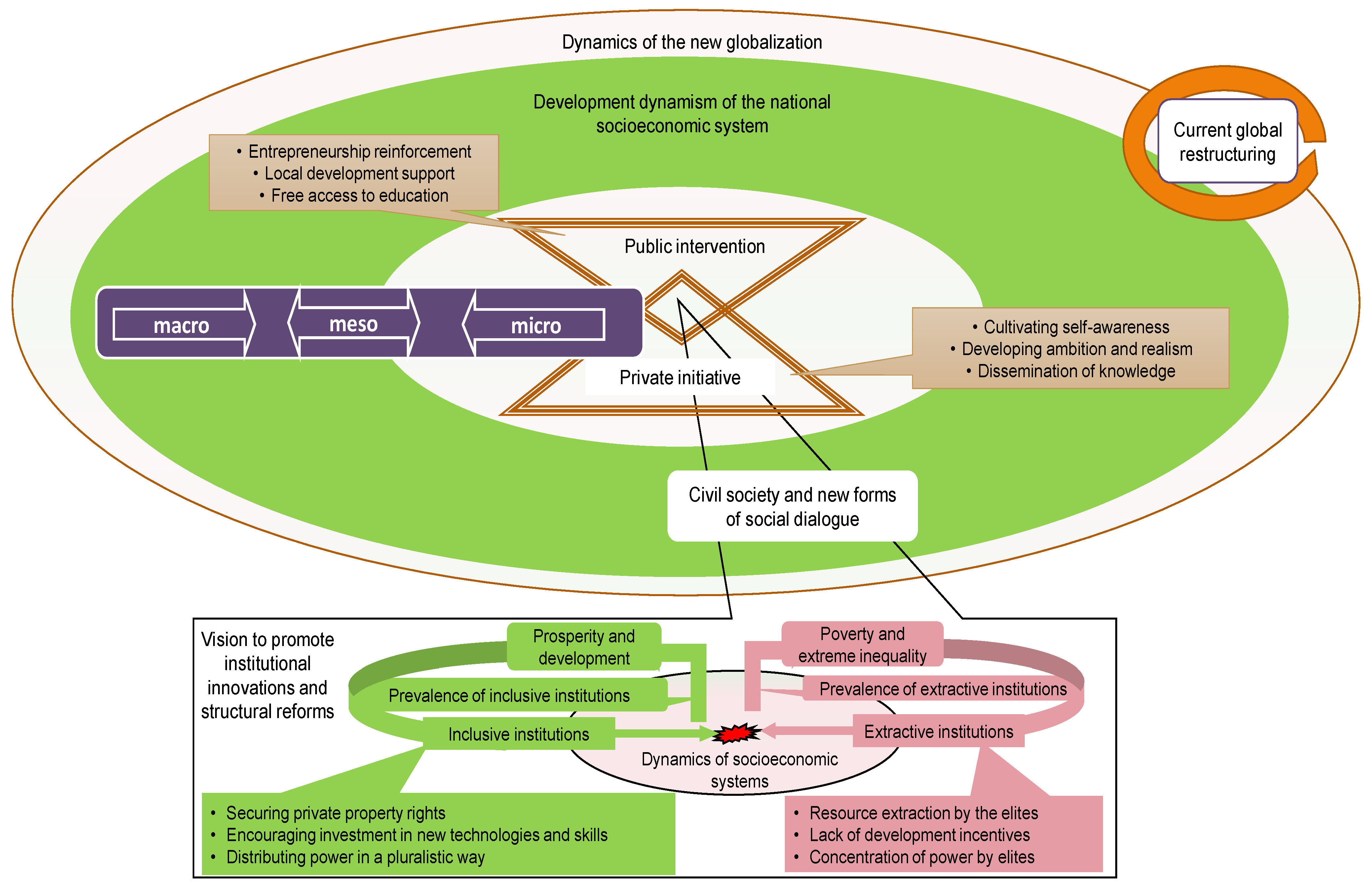

- The accelerated 4IR can also explain why the labor market is profoundly restructured these days. Digital transformation is essential for all socioeconomic organizations nowadays. To some extent, developing “cyber-physical” systems is a necessity—particularly for less adaptable employers and employees—as they can only be built on top of new knowledge and soft skills. However, avoiding new forms of exclusion and labor inequalities caused by digital technologies is undoubtedly a significant emerging challenge. Most countries have not used effective social partnership schemes to deal with today’s global transitional period. Thus, additional research on formulating socioeconomic policies to exit the crisis seems to be needed based on frameworks that promote institutional innovations and adequate macro–meso–micro public–private partnerships;

- (D)

- Additionally, developing new organizational forms of environmental awareness—simultaneously, at the level of central management and employees (from top to bottom and vice versa)—seems to be an essential adaptive feature for organizations aiming at their own innovative greenness. The hastened energy transition (see the war in Ukraine) seems to confirm this central environmental concern and the need to promote organic innovations. The green change management dimensions we have introduced could trigger further studies addressing climate change through mechanisms that promote organizational resilience, adaptability, sustainability, and inclusiveness;

- (E)

- We finally consider the microlevel potential of organizational adaptation as an inextricable—and perhaps the most significant—link to all organizations’ survival and development. This paper supported the argument that innovation is the only way to exit the crisis based on adequate change-management mechanisms. We think further research could better integrate present-day organizational transformation programs into the fundamental theoretical perspectives of change management. The conceptual scheme we introduced in Figure 3 can be used as a compass for change practitioners in these turbulent times and help socioeconomic organizations improve their strategy, technology, and management.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Post-Fordisms are a variety of socioeconomic configurations in different countries of advanced production and consumption, mainly in the developed capitalist states, and came about as a response to the crisis of Fordism after the 1980s. The expanding economies of scope and different configurations in production and consumption systems and the restructuring of the welfare state in different countries were the hallmarks of this theoretical growth-crisis platform, as specialization and client specificity played a leading role in product strategy [130]. |

| 2 | Many enterprises have adopted hybrid working models, combining face-to-face and virtual work. However, remote workers have often reported a lack of satisfaction and alienation. Some have claimed that their new way of working has improved their everyday life and increased their leisure time by dramatically reducing commuting and other pertinent costs [131]. Conversely, the opponents of remote work have underlined that working outside the traditional office environment is likely to cause increased working hours and unsociable schedules, which could increase employees’ psychological risk, stress, and uncertainty [132]. Also, employees from home can be obliged to pay a portion of their working expenses—e.g., broadband availability and equipment costs [133]. |

| 3 | Within traditional workplaces, the need for better health and safety standards—such as minimizing overcrowding—seems imperative for white-collar workers in the post-COVID-19 era [134]. |

| 4 | The restrictions on work mobility that occurred amid the COVID-19 crisis appear to be transferred in today’s labor environment, giving rise to a novel meaning of the “workplace”, in which outsourcing—and gig workers—could be a competitive advantage for the proactive employers and managers [135]. However, the degree of “telemigration” is affected by the “teleworkability” of each profession, causing a new digital divide [136]. |

| 5 |

References

- Bonilla-Molina, L. COVID-19 on route of the Fourth Industrial Revolution. Postdigit. Sci. Educ. 2020, 2, 562–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaind, N.; Else, H. Global research community condemns Russian invasion of Ukraine. Nature 2022, 603, 209–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osendarp, S.; Verburg, G.; Bhutta, Z.; Black, R.E.; de Pee, S.; Fabrizio, C.; Headey, D.; Heidkamp, R.; Laborde, D.; Ruel, M.T. Act now before Ukraine war plunges millions into malnutrition. Nature 2022, 604, 620–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The COVID-19 Crisis Response; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2020.

- Marinov, M.; Marinova, S.T. COVID-19 and International Business: Change of Era; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2021; ISBN 978-0-367-62324-1. [Google Scholar]

- Savić, D. COVID-19 and Work from Home: Digital Transformation of the Workforce. Grey J. TGJ 2020, 16, 101–104. [Google Scholar]

- Neven, L.; Peine, A. From Triple Win to Triple Sin: How a Problematic Future Discourse is Shaping the Way People Age with Technology. Societies 2017, 7, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanelt, A.; Bohnsack, R.; Marz, D.; Antunes Marante, C. A Systematic Review of the Literature on Digital Transformation: Insights and Implications for Strategy and Organizational Change. J. Manag. Stud. 2021, 58, 1159–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delios, A. How can organizations be competitive but dare to care? Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2010, 24, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlados, C.; Koutroukis, T.; Chatzinikolaou, D. Change management, organizational adaptation, and labor market restructuration: Notes for the post-COVID-19 era. In COVID-19 Pandemic Impact on New Economy Development and Societal Change; Popescu, C., Ed.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2022; pp. 1–21. ISBN 978-1-66843-374-4. [Google Scholar]

- Dhakal, S.; Burgess, J.; Connell, J. COVID-19 crisis, work and employment: Policy and research trends. Labour Ind. J. Soc. Econ. Relat. Work 2021, 31, 353–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, H. Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 104, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronin, M.A.; George, E. The Why and How of the Integrative Review. Organ. Res. Methods 2020, 1094428120935507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlados, C.; Chatzinikolaou, D. Macro, meso, and micro policies for strengthening entrepreneurship: Towards an integrated competitiveness policy. J. Bus. Econ. Policy 2020, 7, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnwell, R.; Daly, W. Strategies for the construction of a critical review of the literature. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2001, 1, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatzinikolaou, D.; Vlados, C. The world system’s mutational crisis and the emergence of the new globalization. In Économie Sociale et Crises du XXIe Siècle; Lamotte, B., Ed.; L’Harmattan: Grenoble, France, 2022; pp. 163–192. [Google Scholar]

- Andrikopoulos, A.; Nastopoulos, C. Κρίση και ρεαλισμός [Crisis and Realism]; Propobos Publications: Athens, Greece, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Vlados, C.; Chatzinikolaou, D. Mutations of the emerging new globalization in the post-COVID-19 era: Beyond Rodrik’s trilemma. Territ. Polit. Gov. 2022, 10, 855–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlados, C.; Chatzinikolaou, D. Evolutionary transformation of the global system and the COVID-19 pandemic: The search for a new development trajectory. Cyprus Rev. 2021, 33, 127–166. [Google Scholar]

- World Economic Outlook; Countering the Cost-of-Living Crisis; IMF: Washington, DC, USA, 2022.

- Bricout, A.; Slade, R.; Staffell, I.; Halttunen, K. From the geopolitics of oil and gas to the geopolitics of the energy transition: Is there a role for European supermajors? Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2022, 88, 102634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, A.T.; Nižetić, S.; Olcer, A.I.; Ong, H.C.; Chen, W.-H.; Chong, C.T.; Thomas, S.; Bandh, S.A.; Nguyen, X.P. Impacts of COVID-19 pandemic on the global energy system and the shift progress to renewable energy: Opportunities, challenges, and policy implications. Energy Policy 2021, 154, 112322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Economic Prospects; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2020.

- ILO Monitor: COVID-19 and the World of Work, 5th ed.; International Labour Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020.

- Azevêdo, D.G. Trade set to plunge as COVID-19 pandemic upends global economy. In Proceedings of the World Trade Organization Trade Forecast Press Conference; 2020; Volume 8. Available online: https://www.wto.org/english/news_e/pres20_e/pr855_e.htm (accessed on 7 December 2022).

- Matthewman, S.; Huppatz, K. A sociology of COVID-19. J. Sociol. 2020, 56, 1440783320939416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhanom, T. WHO Director-General’s Opening Remarks at the Media Briefing on COVID-19—23 July 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---23-july-2020 (accessed on 7 December 2022).

- Global Humanitarian Response Plan: COVID-19; Palais des Nations: Geneva, Switzerland; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2020.

- Buscemi, M. Outcasting the Aggressor: The Deployment of the Sanction of “Non-participation”. Am. J. Int. Law 2022, 116, 764–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD Economic Outlook; OECD: Paris, France, 2020; Volume 2020, Issue 2.

- Beech, P. Z, V or “Nike Swoosh”—What Shape Will the COVID-19 Recession Take? Available online: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/05/z-u-or-nike-swoosh-what-shape-will-our-covid-19-recovery-take/ (accessed on 8 December 2020).

- Gómez-Pineda, J.G. Growth Forecasts and the COVID-19 Recession They Convey; Centre for Economic Policy Research: London, UK, 2020; pp. 196–213. [Google Scholar]

- Gregory, V.; Menzio, G.; Wiczer, D.G. Pandemic Recession: L or V-Shaped? National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence, M.; Homer-Dixon, T. The Roubini Cascade: Are We Heading for a Greater Depression? Inter-Systemic Cascades; Royal Roads University: Victoria, BC, Canada, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Vlados, C.; Chatzinikolaou, D. Impact of COVID-19 crisis, global transformation approaches and emerging organisational adaptations: Towards a restructured evolutionary perspective. In Business Under Crisis: Contextual Transformations and Organisational Adaptations; Vrontis, D., Thrassou, A., Weber, Y., Shams, S.M.R., Tsoukatos, E., Efthymiou, L., Eds.; Palgrave Studies in Cross-Disciplinary Business Research. In Association with EuroMed Academy of Business; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume II, pp. 65–90. ISBN 978-3-030-76575-0.

- Schumpeter, J. Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy; Taylor&Francis e-Library: Abingdon, UK, 2003; Harper & Brothers: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 1942. [Google Scholar]

- Kondratieff, N.D.; Stolper, W.F. The Long Waves in Economic Life. Rev. Econ. Stat. 1935, 17, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, C. Technological revolutions and techno-economic paradigms. Camb. J. Econ. 2010, 34, 185–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BMBF-Internetredaktion Future Project Industry 4.0—BMBF (Zukunftsprojekt Industrie 4.0—BMBF). Available online: https://www.bmbf.de/de/zukunftsprojekt-industrie-4-0-848.html (accessed on 24 November 2020).

- Schwab, K. The Fourth Industrial Revolution. 12 December 2015. Available online: https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/2015-12-12/fourth-industrial-revolution (accessed on 7 December 2022).

- Schwab, K. The Fourth Industrial Revolution; Crown Business: New York, NY, USA, 2016; ISBN 978-1-5247-5886-8. [Google Scholar]

- Gill, H. A continuing vision: Cyber-physical systems. In Proceedings of the Fourth Annual Carnegie Mellon Conference on the Electricity Industry, Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 10–11 March 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Schlick, J. Cyber-physical systems in factory automation—Towards the 4th industrial revolution. In Proceedings of the 2012 9th IEEE International Workshop on Factory Communication Systems, Lemgo, Germany, 21–24 May 2012; p. 55. [Google Scholar]

- ten Brink, T., VI. Historical Phases of the World Order and the Periodisation of Socio-Economic and Geopolitical Power Relations. In Global Political Economy and the Modern State System; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 115–187. ISBN 90-04-26222-9. [Google Scholar]

- Duménil, G.; Lévy, D. The crisis of neoliberalism. In Handbook of Neoliberalism; Springer, S., Birch, K., MacLeavy, J., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; pp. 551–562. ISBN 978-1-317-54966-6. [Google Scholar]

- Gilpin, R. The Challenge of Global Capitalism: The World Economy in the 21st Century, 2018th ed.; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2000; ISBN 978-0-691-18647-4. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein, J.S.; Pevehouse, J.C. Principles of International Relations; Pearson Logman: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Krasner, S.D. International Regimes; Cornell University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1983; ISBN 978-0-8014-1550-0. [Google Scholar]

- Kindleberger, C.P. The World in Depression, 1929–1939; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1973; ISBN 978-0-520-02423-6. [Google Scholar]

- Keohane, R.O. After Hegemony: Cooperation and Discord in the World Political Economy; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1984; NLB: London, UK, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Aglietta, M. A Theory of Capitalist Regulation: The US Experience; Translation of: “Régulation et Crises du Capitalisme”; Calmann-Lévy: Paris, France, 1976; NLB: London, UK, 1979; ISBN 978-0-86091-016-9. [Google Scholar]

- Boyer, R. The Regulation School: A Critical Introduction; Columbia Univ. Press: New York, NY, USA, 1990; ISBN 978-0-231-06548-1. [Google Scholar]

- Lipietz, A. Towards a New Economic Order: Postfordism, Ecology, and Democracy; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 1993; ISBN 978-0-7456-0866-2. [Google Scholar]

- Boyer, R.; Saillard, Y. (Eds.) Regulation Theory: The State of the Art; Taylor&Francis e-Library: Abingdon, UK, 2005; Routledge: London, UK/New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, R.; Winter, S. An Evolutionary Theory of Economic Change; The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA; London, UK, 1982; ISBN 978-0-674-27228-6. [Google Scholar]

- Schumpeter, J. Business Cycles: A Theoretical, Historical and Statistical Analysis of the Capitalist Process; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 1939. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, R.; Dosi, G.; Helfat, C.; Winter, S.; Pyka, A.; Saviotti, P.; Lee, K.; Malerba, F.; Dopfer, K. Modern Evolutionary Economics: An Overview; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2018; ISBN 978-1-108-42743-2. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, C. The Economics of Industrial Innovation; Penguin: London, UK, 1974; ISBN 978-0-14-080906-0. [Google Scholar]

- Chatzinikolaou, D.; Vlados, C. Evolutionary economics and the Stra. Tech. Man approach of the firm into globalization dynamics. Bus. Manag. Econ. Res. 2019, 5, 146–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothwell, R. Towards the fifth-generation innovation process. Int. Mark. Rev. 1994, 11, 7–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kieh, G.K. (Ed.) Africa and the New Globalization; Ashgate Pub. Company: Aldershot, UK; Burlington, VT, USA, 2008; ISBN 978-0-7546-7138-1. [Google Scholar]

- Dasgupta, S.; Pieterse, J.N. Politics of Globalization; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009; p. 439. ISBN 978-81-321-0828-3. [Google Scholar]

- Strohmer, M.F.; Easton, S.; Eisenhut, M.; Epstein, E.; Kromoser, R.; Peterson, E.R.; Rizzon, E. Disruptive Procurement: Winning in a Digital World; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; ISBN 978-3-030-38949-9. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya, A.; Khanna, D.; Schweizer, C.; Bijapurkar, A. The new globalization: Going beyond the rhetoric. BCG Henderson Inst. 2017. Available online: https://www.bcg.com/en-gr/publications/2017/new-globalization-going-beyond-rhetoric.aspx (accessed on 7 December 2022).

- Killian, L.J. Taming the dark side of the new globalization. In The Palgrave Handbook of Corporate Sustainability in the Digital Era; Park, S.H., Gonzalez-Perez, M.A., Floriani, D.E., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 355–376. ISBN 978-3-030-42412-1. [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin, R. The great convergence: Information technology and the New Globalization; Belknap Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016; Volume 18. [Google Scholar]

- Roach, S.S. The Next Asia: Opportunities and Challenges for a New Globalization; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Directorate-General for External Policies of the Union. The Geopolitical Implications of the COVID-19 Pandemic; European Parliament: Strasbourg, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Braña, F.-J. A fourth industrial revolution? Digital transformation, labor and work organization: A view from Spain. J. Ind. Bus. Econ. 2019, 46, 415–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loureiro, A. There is a fourth industrial revolution: The digital revolution. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2018, 10, 740–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modiba, M.M.; Kekwaletswe, R.M. Technological, organizational and environmental framework for digital transformation in South African financial service providers. Int. J. Innov. Sci. Res. Technol. 2020, 5, 180–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maynard, A.D. Navigating the fourth industrial revolution. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2015, 10, 1005–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ILO Trade Unions in Transition: Interview with Maria Helena André. Available online: http://www.ilo.org/actrav/media-center/news/WCMS_776264/lang--en/index.htm (accessed on 26 June 2021).

- Pattenden, J.; Campling, L.; Ballivián, E.C.; Gras, C.; Lerche, J.; O’Laughlin, B.; Oya, C.; Pérez-Niño, H.; Sinha, S. Introduction: COVID-19 and the conditions and struggles of agrarian classes of labour. J. Agrar. Change 2021, 21, 582–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderón-Gómez, D.; Casas-Mas, B.; Urraco-Solanilla, M.; Revilla, J.C. The labour digital divide: Digital dimensions of labour market segmentation. Work Organ. Labour Glob. 2020, 14, 7–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, W.; Jarrahi, M.H.; Dunn, M.; Nelson, S.B. Work Precarity and Gig Literacies in Online Freelancing. Work Employ. Soc. 2020, 34, 457–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ando, S.; Balakrishnan, R.; Gruss, B.; Hallaert, J.-J.; Jirasavetakul, L.-B.F.; Kirabaeva, K.; Klein, N.; Lariau, A.; Liu, L.Q.; Malacrino, D. European Labor Markets and the COVID-19 Pandemic: Fallout and the Path ahead; IMF: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Eaton, A.; Heckscher, C. COVID’s Impacts on the Field of Labour and Employment Relations. J. Manag. Stud. 2021, 58, 275–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markey, R. The impact of the COVID-19 virus on industrial relations. Impact COVID-19 Virus Ind. Relat. 2020, 85, 147–154. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, C. Boost supply, not demand, during the pandemic. The Hill. 2020. Available online: https://thehill.com/blogs/congress-blog/economy-budget/488373-boost-supply-not-demand-during-the-pandemic/ (accessed on 7 December 2022).

- Pouliakas, K.; Wruuck, P. Corporate Training and Skill Gaps: Did COVID-19 Stem EU Convergence in Training Investments? Institute of Labor Economics (IZA): Bonn, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Stantcheva, S. Inequalities in the Times of a Pandemic; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2022; p. w29657. [Google Scholar]

- Hlasny, V.; AlAzzawi, S. Last in After COVID-19: Employment Prospects of Youths during a Pandemic Recovery. In Proceedings of the Forum for Social Economics; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2022; Volume 51, pp. 235–244. [Google Scholar]

- Adamowicz, M. COVID-19 Pandemic as a Change Factor in the Labour Market in Poland. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palomino, J.C.; Rodríguez, J.G.; Sebastian, R. The COVID-19 shock on the labour market: Poverty and inequality effects across Spanish regions. Reg. Stud. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, A.; Fiers, F.; Hargittai, E. Participation inequality in the gig economy. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clare, B.; Julia, L.; Smith, K.E. The Unequal Pandemic: COVID-19 and Health Inequalities; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2021; ISBN 978-1-4473-6125-1. [Google Scholar]

- van Barneveld, K.; Quinlan, M.; Kriesler, P.; Junor, A.; Baum, F.; Chowdhury, A.; Junankar, P.; Clibborn, S.; Flanagan, F.; Wright, C.F.; et al. The COVID-19 pandemic: Lessons on building more equal and sustainable societies. Econ. Labour Relat. Rev. 2020, 31, 133–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krafft, C.; Assaad, R.; Marouani, M.A. The Impact of COVID-19 on Middle Eastern and North African Labor Markets; The Economic Research Forum: Dubai, Arab, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Fay, D.L.; Ghadimi, A. Collective Bargaining during Times of Crisis: Recommendations from the COVID-19 Pandemic. Public Adm. Rev. 2020, 80, 815–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triantafillidou, E.; Koutroukis, T. The Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on The Work Landscape and Employment Policy Responses: Insights from Labor Policies Adopted in The Greek Context. Eur. Sci. J. ESJ 2021, 17, 179–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutroukis, T. Σύγχρονες εργασιακές σχέσεις [Contemporary Employee Relations]; Kritiki Publications: Athens, Greece, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Canalda Criado, S. Social partner participation in the management of the COVID-19 crisis: Tripartite social dialogue in Italy, Portugal and Spain. Int. Labour Rev. 2022, 161, 149–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- COVID-19: Implications for Employment and Working Life; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2021.

- Koutroukis, T.; Kretsos, L. Social dialogue in areas and times of depression: Evidence from regional Greece. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2008, 2, 77–84. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, J.; Zadek, S. Partnership Alchemy: New Social Partnerships in Europe; Copenhagen Centre; BLF: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2000; ISBN 87-987643-1-4. [Google Scholar]

- Raffaelli, R.; Glynn, M.A. Institutional Innovation: Novel, Useful, and Legitimate. In The Oxford Handbook of Creativity, Innovation, and Entrepreneurship; Shalley, C., Hitt, M.A., Zhou, J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2015; pp. 407–420. [Google Scholar]

- Koutroukis, T. Social Dialogue in Post-crisis Greece: A Sisyphus Syndrome for Greek Social Partners’ Expectations. In The Internal Impact and External Influence of the Greek Financial Crisis; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 71–83. [Google Scholar]

- Koutroukis, T.; Roukanas, S. Social Dialogue in the Era of Memoranda: The Consequences of Austerity and Deregulation Measures on the Greek Social Partnership Process. In The First Decade of Living with the Global Crisis: Economic and Social Developments in the Balkans and Eastern Europe; Karasavvoglou, A., Aranđelović, Z., Marinković, S., Polychronidou, P., Eds.; Contributions to Economics; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 73–82. ISBN 978-3-319-24267-5. [Google Scholar]

- Acemoglu, D.; Robinson, J.A. Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty; Profile Books: London, UK; New York, NY, USA; Crown Publishers: London, UK, 2012; ISBN 978-1-84765-461-8. [Google Scholar]

- Chatzinikolaou, D.; Vlados, C. Searching for a new global development trajectory after COVID-19. Int. J. Glob. Environ. Issues 2022, 21, 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulze-Cleven, T.; Farrell, H. Toward Institutional Innovation in US Labor Market Policy: Learning from Europe? Berkeley Roundtable on the International Economy; University of California: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Vlados, C.; Chatzinikolaou, D. Crisis, institutional innovation and change management: Thoughts from the Greek case. J. Econ. Polit. Econ. 2019, 6, 58–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrovskaia, I. COVID-19 and Labour Law: Russian Federation. Ital. Labour Law E-J. 2020, 13, 10791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Working from Home: From Invisibility to Decent Work; International Labour Office: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021.

- Collings, D.G.; Nyberg, A.J.; Wright, P.M.; McMackin, J. Leading through paradox in a COVID-19 world: Human resources comes of age. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2021, 31, 819–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triantafillidou, E.; Koutroukis, T. Employee Involvement and Participation as a Function of Labor Relations and Human Resource Management: Evidence from Greek Subsidiaries of Multinational Companies in the Pharmaceutical Industry. Adm. Sci. 2022, 12, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora Cortez, R.; Johnston, W.J. The Coronavirus crisis in B2B settings: Crisis uniqueness and managerial implications based on social exchange theory. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2020, 88, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Global Trend Analysis of the Role of Trade Unions in Times of COVID-19: A Summary of Key Findings (Executive Summary); International Labour Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021.

- Kifor, C.V.; Săvescu, R.F.; Dănuț, R. Work from Home during the COVID-19 Pandemic—The Impact on Employees’ Self-Assessed Job Performance. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2022, 19, 10935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamouche, S. Human resource management and the COVID-19 crisis: Implications, challenges, opportunities, and future organizational directions. J. Manag. Organ. 2021, 1, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nutsubidze, N.; Schmidt, D.A. Rethinking the role of HRM during COVID-19 pandemic era: Case of Kuwait. Rev. Socio-Econ. Perspect. 2021, 6, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, S.P.; dos Santos, J.V.; Silva, I.S.; Veloso, A.; Brandão, C.; Moura, R. COVID-19 and People Management: The View of Human Resource Managers. Adm. Sci. 2021, 11, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulaiman, M.a.B.A.; Ahmed, M.N.; Shabbir, M.S. COVID-19 challenges and human resource management in organized retail operations. Utop. Prax. Latinoam. 2020, 25, 81–92. [Google Scholar]

- Kirton-Darling, J.; Barthès, I. Anticipating the COVID-19 restructuring tsunami. Soc. Eur. 2020. Available online: https://socialeurope.eu/anticipating-the-covid-19-restructuring-tsunami (accessed on 7 December 2022).

- Hadjisolomou, A.; Simone, S. Profit over People? Evaluating Morality on the Front Line during the COVID-19 Crisis: A Front-Line Service Manager’s Confession and Regrets. Work Employ. Soc. 2021, 35, 396–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrebiniak, L.G.; Joyce, W.F. Organizational adaptation: Strategic choice and environmental determinism. Adm. Sci. Q. 1985, 30, 336–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanier, I.; Nunan, J. The impact of COVID-19 on UK informant use and management. Polic. Soc. 2021, 31, 512–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanal, P.; Bento, F.; Tagliabue, M. A scoping review of organizational responses to the COVID-19 pandemic in schools: A complex systems perspective. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlados, C. On a correlative and evolutionary SWOT analysis. J. Strategy Manag. 2019, 12, 347–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlados, C. The Stra.Tech.Man Scorecard. Int. J. Bus. Adm. 2021, 12, 36–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzinikolaou, D.; Vlados, C. Crisis, innovation and change management: A blind spot for micro-firms? J. Entrep. Emerg. Econ. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goss, T.; Pascale, R.; Athos, A. The reinvention roller coaster: Risking the present for a powerful future. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1993, 71, 97–106. [Google Scholar]

- Senge, P.M. The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization; Doubleday/Currency: New York, NY, USA, 1990; ISBN 978-0-385-26094-7. [Google Scholar]

- Duck, J.D. Managing change: The art of balancing. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1993, 71, 109–118. [Google Scholar]

- Kotler, P.; Caslione, J.A. Chaotics: The Business of Managing and Marketing in the Age of Turbulence; American Management Association: New York, NY, USA, 2009; ISBN 978-0-8144-1521-4. [Google Scholar]

- Covey, S.R. Principle-Centered Leadership: Teaching People How to Fish; Executive Excellence: Provo, UT, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Reimagining Policy-Making in the Fourth Industrial Revolution; World Economic Forum Agile Governance: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

- World Economic Forum Leading through the Fourth Industrial Revolution: Putting People at the Centre; World Economic Forum: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- Boyer, R.; Durand, J.-P. (Eds.) After Fordism; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 1993; ISBN 978-0-333-65788-1. [Google Scholar]

- Manokha, I. COVID-19: Teleworking, Surveillance and 24/7 Work. Some Reflexions on the Expected Growth of Remote Work After the Pandemic. Polit. Anthropol. Res. Int. Soc. Sci. PARISS 2020, 1, 273–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Living, Working and COVID-19; COVID-19 Series; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2020.

- Kooij, D.T. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on older workers: The role of self-regulation and organizations. Work Aging Retire. 2020, 6, 233–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schall, M.C.; Chen, P. Evidence-based strategies for improving occupational safety and health among teleworkers during and after the coronavirus pandemic. Hum. Factors 2021, 64, 0018720820984583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedland, J.; Balkin, D.B. When gig workers become essential: Leveraging customer moral self-awareness beyond COVID-19. Bus. Horiz. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sostero, M.; Milasi, S.; Hurley, J.; Fernandez-Macias, E.; Bisello, M. Teleworkability and the COVID-19 Crisis: A New Digital Divide? European Commission: Seville, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hodgson, G. The Mecca of Alfred Marshall. Econ. J. 1993, 103, 406–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzinikolaou, D.; Vlados, C. Schumpeter, neo-Schumpeterianism, and Stra. Tech. Man evolution of the firm. Issues Econ. Bus. Int. Econ. Bus. 2019, 5, 80–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Hegemonic Stability Theory: International Regime | Regulation School: Development–Crisis Theoretical Platform | Evolutionary Socioeconomic Approach: Generations of Innovation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1945–1973: First postwar international growth and national development period | US hegemony and the power of bipolarity | Fordist growth | Aggregative innovation |

| 1973–1980: Crisis and pre-globalization period | Bipolar system’s crisis | Fordist crisis | Combinational innovation |

| 1980–2008: Globalization period | Gradual transition to the post-Cold war period | Globalized post-Fordisms | Integrated innovation |

| 2008–New or restructured globalization period | Seeking a new multipolarity | Searching for realistic hybrid post-Fordisms | Quest for an organic, ecosystemic, and open innovation |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Koutroukis, T.; Chatzinikolaou, D.; Vlados, C.; Pistikou, V. The Post-COVID-19 Era, Fourth Industrial Revolution, and New Globalization: Restructured Labor Relations and Organizational Adaptation. Societies 2022, 12, 187. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc12060187

Koutroukis T, Chatzinikolaou D, Vlados C, Pistikou V. The Post-COVID-19 Era, Fourth Industrial Revolution, and New Globalization: Restructured Labor Relations and Organizational Adaptation. Societies. 2022; 12(6):187. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc12060187

Chicago/Turabian StyleKoutroukis, Theodore, Dimos Chatzinikolaou, Charis Vlados, and Victoria Pistikou. 2022. "The Post-COVID-19 Era, Fourth Industrial Revolution, and New Globalization: Restructured Labor Relations and Organizational Adaptation" Societies 12, no. 6: 187. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc12060187

APA StyleKoutroukis, T., Chatzinikolaou, D., Vlados, C., & Pistikou, V. (2022). The Post-COVID-19 Era, Fourth Industrial Revolution, and New Globalization: Restructured Labor Relations and Organizational Adaptation. Societies, 12(6), 187. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc12060187