Abstract

This article explores arts, cultural and community engagement (ACCE) in the context of enduring austerity in England. Working with a methodically crafted synthesis of theoretical perspectives drawn from (1) the critical political economy (CPE) tradition, (2) the sociology of cultural production, (3) cultural studies and critical strands of community development scholarship, and (4) pertinent discourses on the creative economy and place-based development, the article reviews the political, economic and institutional ecosystem within which a bottom-up approach to ACCE operates. Making use of ethnography for data-gathering, the article explores how three carefully selected case studies respond to the demands and pressures generated by, and associated with, corporate interest and top-down, policy-driven subsidy—including how such responses shape and position the work of the case studies in the contemporary creative economy and local place-based development. The article argues that ACCE contributes meaningfully to the development of self-governance and organic growth through egalitarian cross-sectoral alliances and cultural and social entrepreneurship. However, this happens only if the said ecosystem genuinely supports equality and social justice. Where such support is non-existent, established hierarchies perpetuate domination and exploitation. This stifles wider creative and cultural engagement on the terms of communities.

1. Introduction

This article explores the current state of arts, cultural and community engagement (ACCE) in the context of enduring austerity in England. The article conceptualises ACCE as a realm of varied activity in which individuals, communities, publics and organisations play a role in determining and shaping their local cultural provision to foster communal growth and to deliver a range of benefits in their urban locales [1,2]. Following acknowledgement of the main versions of ACCE that exist, the article specifically focuses on the brand of ACCE that employs a community-driven, bottom-up approach to, and hybrid mode of, creative and cultural engagement—some of whose main aspirations, visions and values are rooted in the ‘radical’ and ‘alternative’ modes of cultural production originating in the countercultural era [3,4,5,6]. Working with a methodically crafted synthesis of theoretical perspectives drawn from (1) the critical political economy (CPE) tradition, (2) the sociology of cultural production, (3) cultural studies and critical strands of community development scholarship, and (4) relevant discourses on the creative economy and place-based development, the article reviews the political, economic and institutional ecosystem within which ACCE operates. Particular emphasis is placed on the demands and pressures generated by, and associated with, corporate interest and top-down, policy-driven subsidy. Employing ethnographic fieldwork for data collection, the article examines how a carefully selected sample of three case study ACCE organisations and their respective practitioners respond to the said demands and pressures, and the ways in which those responses shape and position the work of the case studies in the contemporary creative economy and local place-based development.

The overarching finding is as surprising as it is illuminating. Despite austere conditions, where the political, economic and institutional ecosystem is genuinely changing in support of equity, fairness and social justice—it enables ACCE to contribute helpfully to the development of self-governance approaches, genuine empowerment, meaningful participation and organic growth on the terms of individuals, communities and publics in their urban locales. This is increasingly happening in the context of multistakeholder alliances in a scope broader than appears to have been the case in the past. This development is characterised by a threefold dimension: (1) it is clearly bucking the trend during these ongoing austere times, (2) it is showing huge potential for serving the creative economy and local place-based development in ways that individuals, communities and publics can identify with and relate to, and (3) it is pointing to the promise of sustaining organic, creative engagement and growth through cultural and social entrepreneurship. The said alliances, however, risk generating dependence. Conversely, where equality and social justice are disregarded in political, economic and institutional relations—ACCE is misappropriated to serve the ideologies and interests of established hierarchies comprising powerful elites, corporate business and bureaucratic actors. This points to neoliberal business as usual which not only stifles community-driven, bottom-up ACCE, but also perpetuates control, domination, exploitation and inequity.

2. Research Design, Method and Case Studies

This article discusses the austere environment and challenging political, economic and institutional ecosystem in which ACCE operates. In doing so, it explores the ways in which that environment and ecosystem are characterised by sometimes conflicting imperatives that pull in different directions. The article asks the following research questions:

- (1)

- How are contemporary ACCE practitioners responding to the demands and pressures generated by, and associated with, corporate interest and top-down, policy-driven subsidy in their work?

- (2)

- How do those responses shape and position the work of ACCE practitioners and their organisations in the contemporary creative economy and local place-based development?

Drawing on ongoing ethnographic research on modes of production and organisation in arts and cultural work in community settings in England1, this article takes three organisations as case studies which display: (1) a demonstrable commitment to, and a strong track record of, engagement with local communities around the arts, culture, heritage, and place-based development, and (2) a subscription to the conceptualisation and role of ACCE as described under Section 3 below. In the capacity as a participant and non-participant observer in 2019 at the organisations specified below, I conducted interviews with three ACCE practitioners who hold organisational roles at leadership and management level. A key pattern that binds these practitioners together is that they belong in the communities and local urban environments in which their organisations operate. The semi-structured interviews as well as participant and non-participant observation were complemented by the study of accessible documentary evidence relating to the case studies encompassing annual company records, project information, newspaper articles, output reviews, websites, blogs, brochures, and social media presence where applicable. Later in the analytical discussion in Section 7 and Section 8, the main websites and newspaper articles studied are cited. In compliance with the ethical terms under which access was granted to carry out this research, the real names of the interviewees—and those of their organisations—are presented throughout. The case studies comprise the Black Sheep Collective (BSC) in Wolverton (Milton Keynes), Cambridge Community Arts (CCA) and Escape Arts (EA) in Stratford-upon-Avon (West Midlands).

BSC is a community interest company (CIC)2 that delivers a range of artistic and creative services to private and public organisations. Founded in 2013, BSC’s services have encompassed research and development, consultancy, design and digital media, advice and guidance, project and event management, evaluation, training and programming. BSC works to social progress indicators (SPI) understood as outcomes that create the conditions for communities and local urban places to reach their full potential and to enhance and sustain their quality of life. Cambridge Community Arts (CCA) is a not-for-profit company providing a programme of creative learning opportunities targeting people at risk of social exclusion. Since its inception in 2014, CCA’s work has been built around a community learner-centred approach that not only uses creativity in all its forms to enable people to improve their health, but also helps them to set up self-run, creative clubs following completion of learning. The ultimate goal is to empower communities through capacity-building.

Registered as a charity in 2003—but technically in existence since 1997, Escape Arts (EA) uses the arts, heritage and culture to bring people together to improve wellbeing and to build strong communities. It achieves this not only through its creative health programme which it delivers with a number of cross-sectoral partners, but also through individual and collective storytelling as well as place-making initiatives. Of the three companies, BSC records ninety per cent trade income and ten per cent grant funding while CCA and EA—by virtue of their charitable status—secure their core income from state-funded grants. By design, the research presented here is limited to England. It focuses on ethos, values, practitioner motivations and expertise, practice, organisational development, modes of engagement and strategies for the negotiation of divergent imperatives at the centre of ACCE as (1) experienced and articulated by the practitioners under study, and as (2) identified and interpreted through the process of data analysis3. It also presents case studies that are reflective but not representative of ACCE. Nevertheless, generalisability is possible considering that emergent themes are likely to be of relevance to cultural engagement contexts elsewhere mediated by shared global political, economic and institutional relations.

3. Understanding Arts, Cultural and Community Engagement (ACCE)

I conceptualise ACCE as a sphere of activity in which ‘the instrumental role of culture is [operationalised] in relation to community [with a particular] focus on issues around democracy and social inclusion, or […] on inspiring individuals to engage with creative practice as a first step towards involvement in the creative economy’ [7] and elsewhere. To Andrew Thompson—the former highest-ranking executive (2015–2019) at England’s Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) which funds creative and culture-related research—ACCE is about harnessing ‘the kinds of benefit that culture may have for society, for communities, for democracy, for public health and wellbeing, for urban life and regional growth’ [2] (p. 5) in a way that other culture-based approaches and interventions may not be able to. Building on this, the Arts Council England4 sees ACCE in action ‘when communities are involved in shaping their local cultural provision, a wider range of people participate in publicly funded cultural activity [and] greater civic and social benefits are delivered [as a result of collaboration between ACCE practitioners and communities]’ [8] (p. 37). Through ACCE work, ‘[c]ulture and the experiences it offers can have a deep and lasting effect on places and the people who live in them [something that] helps improve lives, regenerate neighbourhoods, support local economies, attract visitors and bring people together’ [8] (p. 37).

There are several versions of ACCE that are impelled by a wide range of aims, desires, incentives and visions5. For instance, one version is state-led and takes a top-down approach to creative and cultural engagement [3,9,10], another is community-driven and typically employs a bottom-up approach [11,12,13,14], and yet the arts and cultural practitioner-led version fuses aspects of the first two approaches [15,16,17,18], thereby taking a hybrid format. Please see Table 1 below for a list of the overarching versions. The brand of ACCE that I am concerned with and analyse in this article typically exhibits the community-driven, bottom-up approach to, and hybrid format of, creative and cultural engagement—in part informed by ‘radical’ and ‘alternative’ approaches to producing culture dating from the countercultural era6. It comprises non-conventional processes, activities and projects that are aimed at change broadly considered, are inspired by a plethora of beliefs, values, methods and lifestyles—individual and collective alike, and tend to be critical, subversive and emancipatory in nature [14] (pp. 91–92) though not necessarily always so.

Table 1.

Main versions of community engagement in cultural and creative engagement.

This ACCE brand has been said to offer avenues and opportunities to pursue social, political, cultural, economic and health and wellbeing agendas and aspirations in a bid to effect change broadly defined by means of opposition and resistance as much as by participation and consent [19]. At its most effective, this form of ACCE has been found to mobilise communities and publics around shared affinities, needs and wants and to offer experiences and services that might otherwise be out of reach [5,14,20,21]. However, as with all engagement with the arts and culture, ACCE as conceptualised so far does not operate in a vacuum, but in a wider and specific ecosystem characterised by powerful political, economic and institutional relations known to pull in different (and sometimes conflicting) directions. It is to the discussion of these relations that the article now turns.

4. The (Critical) Political Economy of Arts, Cultural and Community Engagement

The powerful political, economic and institutional relations mentioned above are best examined through the critical political economy (CPE) tradition which is a useful conceptual framework for exploring power relations, resource allocation and social justice considerations as they relate to the regulation, ownership, organisation, production, dissemination, consumption of, and engagement with, culture widely considered [22,23,24,25]. In the exploration of these key aspects, CPE distinguishes itself from other strands of political economy by moving beyond considerations of technical matters of control, competition, cost reduction and efficiency, funding, productivity and profit maximisation and engaging with basic moral questions of justice, equity and the public good [26,27,28].

From the perspective of the arts, culture, heritage, and place-based development, the aspects mentioned above have been studied through cultural polices and corresponding state support, organisational development and related business models, creative expression and associated artistic traditions, technologies, markets and texts among other things [6,10,18,20,29,30,31,32,33]. As ACCE has evolved over the decades, so have the perspectives informing CPE in an effort to account for the considerable changes that have displaced established and familiar ways of engaging with culture. Such changes have ranged from adjusting to the evolution of the structures, remit and ways of working informing ACCE to contending with the increasing influence of neoliberalisation ideology and related policy mechanisms to navigating the balance between local agendas and regional, national and global imperatives to negotiating emergent moral and ethical issues that result from an ACCE landscape in a state of flux [7,34,35,36].

CPE informs our understanding of how communities of practitioners and organisations championing ACCE deal with change and uncertainty in two interconnected ways. First, CPE approaches the analysis of ACCE at three levels, namely macro (industrial structure), meso (middle or intermediate sectoral formation) and micro (intra-organisational configuration) in its quest to offer a balanced analysis between neoliberal interests and associated capitalist enterprise on the one hand, and state intervention in the interests of the broader public good on the other [25,27,37]. Scholarship has consistently found that not only does the way in which resources are allocated always favour some (usually a privileged few) at the expense of others, but the mechanics behind this reinforce and sustain powerful elitist world views and existing capitalist structures at the macro level [23,38,39,40,41]. Second, in proceeding this way—CPE integrates other cultural, organisational and sociological theoretical approaches to probe the relationship between the structure of the cultural and creative industries and agency at the intermediate ACCE sector and micro-organisational levels while paying close attention to how output generation is affected [1,6,24,42]. I identify three such approaches—carefully crafted syntheses of which work particularly well for my purposes in this article namely (1) the sociology of cultural production, (2) cultural studies and critical strands of community development scholarship, and (3) pertinent discourses on the creative economy and place-based development.

Placing emphasis on conventions, practices, relations, resources and questions of equity at the intermediate (sectoral) and micro (organisational) levels, the sociology of cultural production examines how shifting production interactions and patterns shape the kinds of artistic outputs created and the range of experiences and modes of engagement generated. It focuses on work routines, practitioner motivations—including their beliefs, biographies, expertise and aptitude, creative expression and artistic traditions subscribed to within arts and cultural worlds of work [38,40,43]. The ways in which ACCE practitioners exercise individual and collective agency in their work worlds—both within and outside of institutional constraints—is of paramount importance. These practitioners forge, construct and iteratively revise their identities, legitimate the value of their work, devise strategies and practices to cope with constant change and uncertainty in the volatile political, economic and institutional ecosystem mentioned earlier, and connect and interact with differently situated constituencies in ways that reveal much about the (un)changing politics and economics of ACCE—including its sometimes evolving relationship with dominant institutional forces [6,26,31,44,45].

A mix of selected perspectives from cultural studies and critical strands of community development scholarship also picks up the facet of agency. The perspectives look at how various constituencies such as individuals, communities and publics make connections between arts and cultural engagement and perceived forces of domination and oppression, attempt to resist such forces by appropriating engagement on their own terms, and contribute to struggles for alternative ways of doing things and broader social change [20,46,47,48]. In doing so, agency in this context pursues a threefold objective that analyses (1) the nature and meaning of the experiences, texts, discourses and services created—and how these are read, interpreted and/or interacted with, (2) the context within which these are consumed and/or engaged with, (3) and the profiles of the individuals, communities and publics at the centre of that engagement [49,50,51]. For Ledwith [52] (pp. 2–3), this engagement is ‘founded on a process of empowerment and participation’—one that ‘involves a form of critical education that encourages people to question their reality [beginning] in the personal everyday experiences that shape people’s lives’. This engagement—as we shall see later—has at times taken a subversive approach to working and has affirmed visions and practices that demonstrably strive to promote a more just and egalitarian social and economic order in community and related place contexts.

Pertinent discourses on the creative economy and place-based development fit in here insofar as government policies support perceived innovative modes of ACCE as a means to revive the economic and cultural life of contemporary communities and local places [7,45]. The employment of ACCE in this way has been said to be a result of the fusion between culture, creativity and the economy that has foregrounded the role of creative industries in economic development and community and local urban renewal [33,53,54]. Drawing heavily on the concepts of the ‘creative city’ [55] and the ‘creative class’ [56]—both of which advocate a move away from industrial and post-industrial societies characterised by the production of goods to societies driven by the generation of ideas and innovation, this top-down approach has championed the need to develop creative solutions to the myriad challenges and problems afflicting communities and local places. This has involved harnessing local cultural infrastructure and resources to boost community and urban revitalisation and cultivating a distinctive image through innovative creative and cultural offerings [32,36,57,58]. The approach has also been closely connected to discourses of placemaking and/or place-based development [21,59] which view communities and local urban settings as ‘demarcated space[s] of governance and regulation, […] of shared cultural meanings that engender a sense of belonging, [and of] relational entit[ies] shaped by [their] relations with others within larger networks [and] the movement of capital and economic strategies’ [60] (p. 2). To Courage [61] (p. 623), the interplay of these factors ‘has an improvement function to better the material quality of public space [including] the quality of lives within it’.

Though desirable in many respects, critical voices have pointed to the instrumental, tokenistic and at times discriminatory nature of this approach. The critique has particularly taken issue with the approach’s privileging of economic-driven interests, entrepreneurial agendas and commercially viable outputs over non-commodifiable outputs, experiences and modes of engagement [16,26,40,62]. It has been argued that the conception of the creative economy in this way has led to policy decisions that not only disenfranchise other types of cultural production and engagement—despite their proven contribution to the wider public good, but also neglect communities and local urban places perceived as deprived and unattractive [3,21,63,64]. In this narrative, the engagement with creative activity and culture is less about the pursuit of cultural forms and practices by communities and various publics in their own local urban ecologies and on their own terms, and more about top-down deployment of culture as part of government agendas to pursue economic growth and sustainable development often in large metropolitan areas deemed conducive to economic investment and renewal [45,54,65].

In line with the neoliberal ideology mentioned earlier, this approach not only privileges the economic exploitation of creativity, culture, labour and resources (broadly considered) over community and cultural interests and needs in local urban settings, but also actively manages, regulates and orders those settings [9,22]. One consequence of this, Edensor and colleagues argue, is that ‘[c]ertain powerful groups [invariably] fix the meanings and functions of [the said settings] through a medley of strategies that [impose and extend domination]’ [60] (p. 4). This raises the overarching question as to what the role of contemporary ACCE in the creative economy and local place-based development is shaping up to become under these circumstances—particularly during the current austere times? Before exploring this question from which the two key research questions formulated in Section 2 have been derived, I find it fruitful to proceed as follows. In the next section, I contextualise the austere environment in England. I hope this context will helpfully inform the reading of the considerable changes ACCE has gradually undergone thus far—and continues to undergo—as a result of the introduction of neoliberal policies, the gradual deconstruction of the welfare state and intra-sectoral turbulence. The said changes are presented in Section 6.

5. Austerity in Context

Whilst many media, public and industry discourses trace the emergence of austerity in England to the 2008/2009 global financial crisis, some prominent scholarly accounts see its origin in the extensive denationalisation programme undertaken by successive Conservative Party governments from the late 1970s and early 1980s onwards. Informed by neoliberalisation and associated capitalist practices, the said governments dismantled the public sector, minimised public provision, considerably reduced state support and committed to non-intervention in the capitalist market while simultaneously engineering privatisation and the mantra of individual freedom and responsibility [1,6,13,18,29,35,37,54,66]. By the mid-to-late 2000s, the said programme—which was inherited by two successive Labour Party governments and the Conservative Party and Liberal Democrat coalition—has been iteratively revised to respond to emerging, major challenges such as ongoing deindustrialisation. The result has been the emergence of a range of service industries, examples of which include information and communication technology, finance and hospitality among others. On the one hand, this phenomenon has often been credited with fostering increased growth in self-employment, higher levels of (individual) entrepreneurship and valuable contributions to the national economy. Indeed, as we shall see later, ACCE is emerging as a mode of cultural and social entrepreneurship that appears to balance the duality between economic benefits and social outcomes for communities and urban locales. On the other hand, it seems paradoxical that a much bleaker overall picture has been painted. Throughout the 2010s, personal incomes have gradually fallen as a result of the ever-rising high cost of living. Workers’ rights have continually been undermined and eroded. Entrepreneurial opportunities have not been readily available to many—and where they have, success (however it is defined) has by no means been guaranteed due to limited or no state support. Unemployment has risen to levels not witnessed in the past. The gap between the wealthy and poor is reported to have dramatically widened—differentially affecting the standard of living and quality of life [3,23,67].

This state of affairs has been exacerbated in the aftermath of the UK’s withdrawal from the European Union and the COVID-19 pandemic [64,68]. Where economic reforms have been undertaken (for instance, the introduction of the minimum wage), they have not been considered radical enough. Where state support has been offered, it has not only tended to be inadequate, but often comes with (neoliberal) strings attached [59,63,67]. A major consequence has been growing inequality and a strong sense of social injustice perpetrated by powerful neoliberal actors and capitalist forces. This structural configuration has meant that many individuals, communities and publics in various locales across England find themselves closer to the lower end of the wealth-poverty spectrum, something that does not bode well for what an equitable and socially just society should look like. There have been repeated appeals to return to the kind of post Second World War British society that foregrounded principles of egalitarianism and universalism—reflected in the prioritisation of public provision of citizens’ basic needs over capitalist interests [29,69,70]. The ultimate goal is to revivify the cultural, economic, political and social development of all [2,7,19,20,40]. For the arts and culture in particular, austerity has meant that mostly wealthy and middle-class individuals are able to engage with the sector—although successive, disproportionate cuts to state subsidy have adversely affected provision [64,69,71]. The key question has been how best to devise imaginative and practical approaches that not only help to trigger and sustain cultural and creative engagement for all, but also markedly and sustainably contribute towards improving the material and immaterial conditions of the citizenry during these austere times? This is the major challenge that the brand of ACCE at the heart of this article seeks to take on.

6. The Regulation and Framing of Arts, Cultural and Community Engagement

Across its history, ACCE has been plagued by misappropriation by established structures [4,6,70]. This has had dire ramifications. Whereas many ACCE practitioners dismissed state support during the late 1960s for fear of being co-opted into the Establishment, a gradual shift in attitude and perception in the 1970s and 1980s meant that so much ACCE came to be funded by public funding—and later business sponsorships—that the ACCE sector found itself heavily dependent on state-sponsored subsidy and corporate funds [4,5,29]. Unsurprisingly, successive subsidy cuts and the unpredictable and restrictive nature of corporate money—coupled with ‘infighting, self-indulgence and obscurantism’ [4] (p. 226) among other things—have crippled ACCE leading to a loss of autonomy and identity. This, in turn, has rendered ACCE ‘relatively weak’ and ‘relatively fragile’ [17] (p. 132), something that has been aggravated by even more ‘de-priorit[isation] in recent rounds of austerity-driven spending cuts’ [17] (p. 133). To borrow Neelands et al.’s words [1] (p. 14), ‘further reduction from current levels of public investment will undermine [ACCE], creating a downward spiral in which fewer creative risks are taken, resulting in less talent development, declining returns and therefore further cuts in investment’. The reinvigoration of ACCE is said to be possible only if rendered ‘an essential part of a new model of public services, one that is built on [wholly supporting community services]’ and ‘aligned with local priorities’ [72] (p. 57). While this may sound plausible on the surface, it points to a top-down, elitist, homogenising, regulatory regime that not only disregards ACCE outside of the mainstream canon [54] (p. 66), but also sees it as a non-statutory service whose de-prioritisation and subsequent funding cuts attract less or no controversy [18,69,70].

It is no wonder, then, that ACCE has been left in a vulnerable position—one in which it has been compelled to forge cross-sectoral collaborations and partnerships to remain relevant and survive. However, this is not without its problems. Commentators have noted that ACCE is now ‘framed in terms of [its] capacity to “fix” the “problems” […] identified by the dominant culture’ [73] (p. 72), is ‘used to reach aims defined through social policy and corporate interest’ [53] (p. 3), and is struggling to ‘stay true to [its] artistic aims in the face of pressure to fit into frameworks imposed from outside’ [17] (p. 133). This way of regulating and framing ACCE does inevitably ‘play into the neoliberal trap that uses notions of community self-reliance as a justification for the withdrawal of state services’ [7] (p. 5). Consequently, ACCE finds itself operating in a landscape ridden with ‘conflicting logics and pressures’ [74] (p. 127) and mediating work increasingly characterised by ephemerality, blandness, partial or whole failure, precarity and even the demise of scores of ACCE practitioners and organisations [7,13,14,69,70,75,76]. Against this background, the article picks up the overarching question posed earlier from which the two research questions presented earlier are derived. Responses follow in the next sections of this article.

7. Balancing Corporate Interest and Top-Down, Policy-Driven Subsidy in Contemporary Arts, Cultural and Community Engagement

In what follows, the article discusses how the practitioners and organisations under examination navigate political, economic and institutional imperatives that can sometimes pull in different directions when going about their day-to-day work. The discussion is structured as follows. Section 7.1 and Section 7.2 respond to the first research question; Section 8, Section 8.1 and Section 8.2 respond to the second research question and situate the discussion in a broader scholarly context. There are overlaps between Section 7 and Section 8 which I hope to be able to highlight—and signpost—effectively when developing analysis. The conclusion is presented in Section 9 at the end.

7.1. Cross-Sectoral Partnerships and Responsible ACCE Growth against All Odds

ACCE practitioners under study in this article acknowledge the complexities and tensions that can emerge when caught between the demands and pressures generated by, and associated with, corporate interest and top-down, policy-driven subsidy on the one hand, and their ACCE work on the other. BSC, for example, takes a pragmatic approach when collaborating with corporate organisations. Of this, Danny Quinn—Executive and Artistic Director—remarks that ‘we have corporate clients who love us because they can invest in us, they can see their pounds going into a social enterprise and filtering out to achieve SPIs [social progress indicators]’. Although Danny Quinn is fully aware that such clients tend to be driven by self-interest reflected in wanting to ‘write a great CSR [Corporate Social Responsibility] report or demonstrate the value of their investment’, what matters most is ‘creating a social economy’ in which diverse, cross-sectoral partners ‘are buying into the idea of Black Sheep’.

Indeed, BSC appears to have honed its CIC model which it uses as a ‘filter’ to facilitate collaborative working amongst stakeholders who may have ‘different ideals’ and ‘different values’ in relation to what a consensual outcome might be—as Danny Quinn notes. He explains that BSC understands that its corporate clients ‘may not understand the artistic value or the artistic merit or the cultural aspirations of [the company’s] work’ nor ‘actually care about the art or who it impacts on’ because ‘[t]hey work in numbers’. Danny Quinn intimates that the clients ask: ‘Well—is it going to bring more people into my venue’, or ‘how much do I get for my pound?’ BSC understands this ‘corporate mindset’ and ‘works as a bit of a filter [before moving] from product to client, from art to audience [and doing this in a way that] translate[s] into languages [artists and clients] understand’. Consequently, ‘the artist gets to do what they do, and the client gets what they want’—according to Danny Quinn. One of BSC’s numerous projects that illustrates this way of working is Fenceless Arts discussed in the next subsection of this article. However, things do not always go swimmingly. Corporate interests—often driven by the neoliberalisation principles described earlier—can favour exploitative structures of control and domination. Those interests can also be obstructive, thereby posing a real threat to social enterprise and community-based agendas [13,52,72,77]. Danny Quinn agrees and remarks that:

Sometimes things just don’t work, sometimes you do have to walk away from things. More often than not, we’ve been lucky enough to not walk from a project because we’ve found a way to subvert it and change it from within… Our company being this filter, we [go]: ‘okay well, we have the power to change the project a bit or change how the [stakeholders] interact, we have that power, and we should use that.

Cambridge Community Arts (CCA) has been undergoing a major period of transition underpinned by ‘scaling up’ and movement away from securing most of its core funding from state-sponsored subsidy to attempting to ‘diversify [its] income revenue stream’ according to Jane Rich—Founder and CEO. This has been reflected in the growth of personnel ‘from one to six in five years’. While this is remarkable for a small organisation, it has not only ‘put pressures on the development of internal systems and finances’ as Jane Rich notes, but also threatened the organisation’s existence which appears rather incongruous. An illustrative example is a period in the organisation’s past where ‘for two years [CCA] had a quarter of the year with no income which had to be patched by a social loan’ as Jane Rich reveals. This derived from the fact that the education-related, state-funded subsidy that CCA receives either ‘is based on an annual contract [which] does not give security’ or is available ‘on a project-basis’. Gradually, however, CCA has worked ‘to develop a secure service’.

Not only has CCA been adept at continually developing its programme of work around using arts and cultural activity to enhance mental health and wellbeing, but also at articulating the transformational impact of that work effectively. This has had a two-fold benefit: (1) CCA has attracted funding from multiple sources which has substantially boosted its profile, and (2) CCA’s high profile within the communities and local places it serves and beyond has meant that its creative course offerings are perennially oversubscribed. This is helping the organisation to reduce dependence on state-sponsored subsidy and, by extension, thwart the impact of any strings attached. Of the organisational development and growth CCA is experiencing, the innovative strategies it is continually developing, and the benefits and impact it is generating for the individuals, communities and publics it serves, Jane Rich observes:

I see it very much as an absence of any alternative similar provision. And the absolute desire of people to engage with others, engage with their creativity, do something positive […] I think that the arts have been wiped out of the school curriculum. There is no community arts. There’s some well-meaning arts organisations doing small projects. But that’s kind of just parachute in, parachute out. There’s no identity in that… And I think people are screaming to be creative [meaning CCA] can only grow.

This commentary conveys three important points: (1) it reinforces the vulnerable position discussed earlier that ACCE work has tended to find itself in in the past, (2) the prevailing circumstances, however austere and unpredictable, paradoxically present an opportunity for ACCE to grow, and (3) ACCE practitioners and the numerous constituencies they serve can utilise creativity and positivity in the context of cultural engagement to make a difference in their everyday worlds. The last two points are exemplified by Jane Rich’s investment in an upskilling course at the London School for Social Entrepreneurs which not only taught her how ‘to grow—and [to do so] responsibly’, but also emboldened her to establish Fenland Community Arts (FCA)—a new arts and cultural organisation in one of Cambridge’s neighbouring rural towns7. Modelled on CCA, FCA now serves ‘a huge area of deprivation [known to have] the highest number of prescriptions for antidepressants in the UK [and struggling with massive cases] of mental health, unemployment and immigration’. Key to the establishment and hitherto success of FCA has been Jane Rich’s skilfulness and resourcefulness in identifying and attracting support in terms of funding, resources and infrastructure. She particularly highlighted the exceptional support provided by the Richmond Fellowship—a national charity that specialises in supporting the delivery of public services such as housing, wellbeing and employment. All CCA’s grant funding appears to align wholly with its ethos, values and practice. The same can be said of the income generated from course offerings which is reinvested in the organisation’s artistic and cultural provision.

Similar to CCA, Escape Arts (EA) secures its core funding from state-sponsored subsidy. Like BSC, EA works with corporate partners and has been proficient not only at choosing them carefully, but also convincing them of the value of its ACCE work. EA has been highly successful in creating, managing and leveraging cross-sectoral partnerships around using creativity to bring people together to improve public health and wellbeing and to reap the kinds of benefit that Andrew Thompson earlier attributes to cultural engagement; facilitating community-building, boosting civic engagement, and improving local urban life and regional growth [2] (p. 5). Getting stakeholders—corporate and non-corporate alike—to pull together as a team as opposed to pulling in different directions ensures that EA can deliver its programme of work without compromising its values and practice since stakeholders ‘have the same ethos as [EA]’ as Karen Williams—co-founder and CEO—notes. EA’s approach is underpinned by stakeholders coming from the areas of education, health and wellbeing, housing and employment—‘all bringing investment, staffing, so it brings the whole programme cost down and so it’s much more sustainable’ according to Karen Williams.

Whereas EA has been in a fortunate position to secure public subsidy along with corporate funds and resources that have consistently aligned with its ethos, two aspects are worthy of mention. First, at one point this culminated in a situation where the organisation became a victim of its own success. Second, prolific as EA is in attracting relatively large grant awards and corporate resources, such support has by no means been infinite. In 2014, EA secured a £1 million award from the Stratford Town Trust community challenge grant scheme to renovate a derelict, 15th Century Tudor pub and slaughterhouse which the organisation made its permanent home a year later8. While renovation was taking place, Karen Williams narrates that EA was awarded ‘a big lottery community grant’9 with which the organisation refurbished ‘an old Warwickshire County Council bus which was due to be scrapped’. The result was ‘this fantastic multimedia bus [which] goes out to lots of different festivals and events’. More on the ‘multimedia bus’ follows in the next subsection of this article.

A further Arts Council England grant was secured around the same time. With a small core team having to ‘project-manage’ the renovation work and grant awards simultaneously—including an attempt to scale up EA’s heritage work with less funding than required, huge problems and tensions were inevitable. Karen Williams intimates that ‘communications broke down because [EA] grew just too quickly, too suddenly [which] split the organisation’, and that the situation ‘took [EA] off in a whole new direction, from being a health and wellbeing charity to running a heritage centre with very limited funding because [EA] didn’t get the full amount of the funding [it] needed for the business plan’. She adds that over ‘the last two years [2017 and 2018], [EA has] worked so hard to get back to: “we are a creative health organisation [who] use the arts and heritage as tools for wellbeing”’. Indeed, a statement on the website of the heritage centre10 reads: ‘CURRENTLY CLOSED. The Heritage Centre is closed to the public until further notice as we are focusing on our charity projects and community workshops’.

By ‘refocus[ing]’ attention on its core ‘objectives’, clearly rearticulating its remit, and devising a strategy ‘underpinning new partnerships and sustainability’ as Karen Williams comments, EA has not only ensured its cross-sectoral partners understand and identify with its ACCE work, but they also profess to being in the partnership for the long haul. For Karen Williams, this allows for ‘much more sustainable’ ways of working that simultaneously keep possible, conflicting interests in check. This appears to have paid dividends. Similar to CCA which established FCA as we have seen above, EA has defied austere conditions by setting up a sister organisation named Nuneaton Escape (NE). Nuneaton is the largest town in Warwickshire11 and is situated in the northern part of that county while Stratford-upon-Avon—where EA is based—is located in the south. NE, therefore, coordinates EA’s work in Nuneaton and across North Warwickshire, something that appears to vindicate Jane Rich’s observation above that there is a demand for community engagement with creativity and culture and an opportunity for ACCE work to grow—austerity notwithstanding.

Overall—and challenges aside, the organisational development and related growth exhibited by EA, CCA and BSC appear to suggest that they are thriving despite operating in an enduring austere climate and unpredictable, broader political and economic ecosystem. Above and beyond the increased opportunities for work—which appear to buck the general austere trend, the balancing act performed by these organisations evokes the concept of ‘aesthetic paradigm’ coined by Felix Guattari—and helpfully reinterpreted by Spiegel and Parent [48]. The narrative is that not only do the case studies embrace different ‘ways of seeing and engaging with the world’ [48] (p. 601), but they also enact ‘experimentation with different kinds of social configurations, ways of working together and of imagining possible futures and modes of both self and collective realisation’ [48] (p. 601). Such configurations at intermediate and micro levels of ACCE are reminiscent of alliances driven by ‘willed affinity’ [43]) that holds those coalitions together until the next destabilising threats emerge from either fixed or changing political, economic and institutional conditions and relations that unsettle existing principles, practices and the very logic of organisational and production contexts.

7.2. Creative Communities, Empowerment and Enterprise

Earlier in the article, we saw how ACCE integrates the process of empowerment and participation informed by thinking and practice from critical community development literature [52,62]. Practitioners at BSC, CCA and EA promote empowerment and participation in different ways in their responses to the demands and pressures generated by, and associated with, corporate interest and top-down, policy-driven subsidy. BSC’s flagship project titled Fenceless Arts, for instance, not only illustrates the organisation’s skilful approach to balancing its ACCE work with corporate interest effectively, but it also highlights community empowerment and participation at its best. According to Danny Quinn, Fenceless Arts ‘is a service’ bought ‘locally’ from BSC by Centre MK—the biggest shopping centre in Milton Keynes12 and the surrounding region—‘to animate its space [through which] 25 million people walk [annually]’. Danny Quinn explains that it involves ‘manag[ing] buskers, performers, community performance, community engagement, community sessions within [Centre MK which] want[s] to show that they are so much more than just another shopping centre—they’re a destination, they’re a place’. What started out as a ‘trial month’ for local and mostly under-resourced artists and cultural performers to ‘animate the space’ has grown into a five-year project that ‘is now huge, [..] happens every day [and] [t]he funding invested in it by Centre MK has grown’.

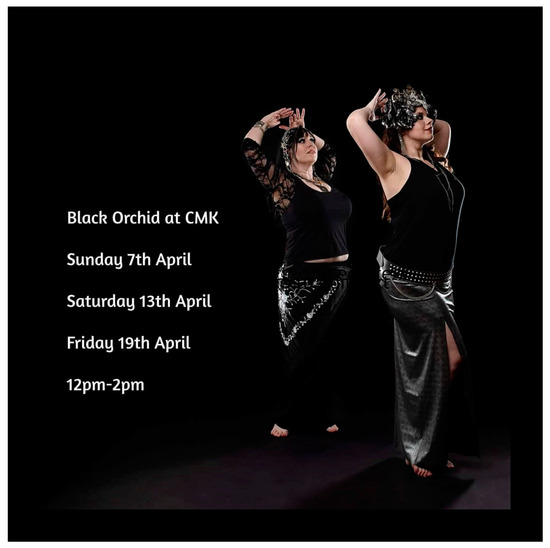

Danny Quinn hinted at ‘so many positives and so many outcomes [which have] changed [local performers’] lives’ through personal empowerment. An illustrative example is ‘one young lady who’ initially played violin in her spare time because she had a full-time job. Danny Quinn narrates ‘[s]he now is a performer […] on [the] programme every day of the week, has quit her job, because she is able to fund her art by selling her CDs, or even just busking or being involved in the project or getting booked by passers-by for events’. He adds that ‘[t]aking that leap for her must’ve been unbelievably scary, but that project gave her the arena to do that’. Interestingly, Danny Quinn does not see Fenceless Arts as being about BSC, but more about the local performers ‘putting themselves out there’. He adds that BSC ‘is there to help, […] to coach and […] to support, [but] not there to govern [because the project] is a whole self-governing system’—one that BSC clearly mediates to leverage the community’s ‘assets […] in the public realm’. This points to a convergence of culture, (social) enterprise as well as economic and social benefits not only in the service of the wider community, but also by and for that community and its local creative economy. Figure 1 below shows a duo of local community belly dancers that perform regularly at Centre MK in the context of the Fenceless Arts project.

Figure 1.

A poster advertising the performances of a duo of community performers called ‘Black Orchid’ at Centre MK. Courtesy of BCA.

We have seen that CCA’s programme of work is strongly supported by grant funding and reinvested surplus income. This has helped the organisation develop an approach that ‘is continual rather than project-based’—according to Jane Rich. The approach is also informed by CCA’s willingness to ‘listen to learner feedback [which always] says: ‘we wish it could be longer, we don’t want this to stop’. Following experimentation with some post-course learning provision as a means of offering a route to progression, CCA established a ‘Creative Clubs’ initiative that enables learners either to set up or join existing clubs which are entirely self-run and independent. Beyond averting ‘the cliff-edge at the end of courses’ as Jane Rich puts it, the clubs play a vital role in helping learner cohorts to remain connected with each other and to support each other through shared activities and interests—insofar as their health and wellbeing allow.

Of the Photography Club, for example—whose members did not know each other prior to the course and displayed ‘very high levels of anxiety in the room’, Jane Rich commented that the ‘group has now been meeting for three years [during which] they have organised field trips and workshops that they run for each other by each other’. The group has grown so much in confidence that ‘[it] offers [its] services to local charities who require event photographers’ (https://www.iclick4u.co.uk/ accessed on 17 May 2021) and holds annual exhibitions including work exhibited at the Tate Exchange in the context of a collaborative, installation project (https://www.kettlesyard.co.uk/events/tate-exchange-2 accessed on 17 May 2021). This clearly points to truly transformational development. Jane Rich remarks that this is just one of ‘many examples of positive life changes from [CCA’s] work [that enable] people to build on their strengths and gain skills that enable them to positively contribute [to their community]’. For her, this is clear evidence of how ACCE work ‘provides the platform to healthier communities empowered by their own creativity’. Figure 2a,b below shows the website of the Photography Club at CCA. Club members have marshalled the creative writing skills and photography competencies they learnt into impressively productive activity which—even if charitable and non-commercial in nature—is not any less valuable than commercial photography.

Figure 2.

(a) CCA Photography Club Website-1; (b) CCA Photography Club Website-2.

The same can be said of EA’s work. Over the last twenty years, EA has been working closely with numerous communities to enhance their health and wellbeing. As in the case of CCA, communities served by EA have expressed their desire to continue engagement with creativity, culture and heritage work even after project-based activities have formally ended. For Karen Williams, constant questions such as ‘can’t we do this in the evening? And can’t we do stuff on our own?’ spur EA on to ‘enabl[e] that to happen’. A key factor to this end has been a strong and collaborative working relationship informed by genuine democratic practice. Karen Williams explains that EA’s work is ‘always [informed by] either somebody’s story or a community need’ which sparks a collective thinking process that ‘kind of grows with conversation’ and ‘consultation’ with ‘lots of stakeholders involved’. Following assessment of workload and feasibility she adds, EA undertakes ‘a few pilot pieces of work [which may] lead to a grant application to underpin the project moving forward’. A case in point is a storytelling project led by a teenager named Bill Jones who interviewed twelve, local D-Day veterans in 2014 and produced a documentary honouring them and their contributions to Stratford and beyond. The film—which was very well-received according to Karen Williams—triggered the establishment of a group named ‘Our Veterans & Interesting Pensioners’ (VIPs) which not only shared and documented stories and memories of local people from past generations, but also inspired others in Stratford to tell their own (hi)stories. Karen Williams narrates that it was this sequence of events that, in turn, inspired the renovation of the dilapidated Tudor pub and slaughterhouse—a site that not only has been so central to the everyday lives of past generations, but also embodies rich social and industrial (hi)stories of the town and region13.

The ‘multimedia bus’ mentioned earlier and the ‘big Lottery grant’ that helped secure it were direct results of this approach. The mobility the bus affords has helped reach numerous deprived and isolated communities and local urban places that benefit from EA’s work the most. A case in point is at Christmas when people from those communities—or others suffering acute levels of hardship—need genuine attention, empathy and ‘a really lovely memory’ as Karen Williams notes. She narrates that the bus is transformed ‘into Santa’s grotto’ and taken to ‘families who can’t access a traditional grotto’ or to children who are unable ‘to leave the house’ due to very serious health conditions. 2018 in particular ‘was completely overwhelming [because EA registered] over 500 visits, 500 contacts […] right across Warwickshire’ as Karen Williams remarks. She says that not only does the bus visit families with members ‘dealing with a terminal illness [who may] potentially [be spending] the last Christmas together’, but also visits ‘Warwick Hospital’. In 2019, the bus was taken to the Hospital along with a community choir for the first time. Figure 3 below shows the multimedia bus in action at a locale in Warwickshire.

Figure 3.

EA multimedia bus on the move in Warwickshire. Courtesy of EA.

8. Contemporary Arts, Cultural and Community Engagement, the Creative Economy and Place-Based Development

Drawing on tried and tested as well as imaginative strategies, ACCE at EA is not only characterised by ‘[taking] art to the community [and] promoting art in and by communities’ [29] (p. 113, italics in original), but also by mobilising people around the arts, culture, heritage and place-based development for instrumental purposes. Its caring, compassionate and nurturing dimension points to the range of benefits that cultural engagement offers—including community-building, capacity development and public health enhancement. EA’s work with the veterans in particular captures this effectively and reinforces national and international research that has found that ‘[g]etting involved in creative activities in communities reduces loneliness, supports physical and mental health and wellbeing, sustains older people and helps to build and strengthen social ties’ [8] (p. 33). EA has established a community hub that not only celebrates local creative and cultural activity, but also preserves local individual and shared memories and stories in a way that leaves a rich and vibrant legacy of past local cultural traditions to the town of Stratford-upon-Avon, surrounding local areas across Warwickshire and posterity.

The same can be said of the work by CCA and FCA. That work supports community groups at risk of exclusion and isolation to use creativity for individual and collective empowerment. In Fenland in particular, this ACCE work is being undertaken in communities and local areas whose ecologies—by the own admission of local and regional government authorities—experience ‘little financial or infrastructure support [and] have limited access to arts opportunities [coupled with] untapped potential [but] where people want to come together, to celebrate and be inspired as a community’ [78] (pp. 3–4). Following years of successive state subsidy cuts, state authorities have been reminded that ‘[t]hrough culture and creative activity, communities can be strengthened and connected more [and that those communities] have [the] willingness and energy to make things happen’ [78] (p. 4).

BSC’s programme of work has shown how barriers can be broken down among differently situated stakeholders through skilful marshalling of community assets and corporate resources for the public good. To borrow Cara Courage’s words, the communities and publics that BSC serves ‘create and recreate the experienced geographies in which they live [drawing on] a networked process “constituted by the socio-spatial relationships that link individuals together through a common place-frame”’ [61] (p. 623). That process ‘involves participation in both the production of meaning and the means of production of [their] locale’ [61] (p. 623). This happens subversively sometimes and nearly always collaboratively. Here, ACCE work clearly demonstrates that various stakeholders in the context of collaborative ventures and partnerships ‘are considered equal contributors’ [11] (p. 165)—something from which two key inferences can be drawn.

8.1. A Favourable Critical Political Economy and ACCE as Cultural/Social Entrepreneurship

The following can be inferred from the collaborative nature of ACCE work. First, ACCE work encompasses the application of tried and trusted and innovative ‘strategies for increasing the influence and responsibility of communities over the [determination of their everyday worlds], either directly or through involvement in cross-sectoral partnerships’ [77] (p. 87). One such strategy is reflected in the cultivation of capacity-building to develop people’s confidence, skills, knowledge, and critical and political consciousness [50,79]. For Ledwith [52] (p. 145), the ultimate goal is to achieve genuine empowerment and meaningful participation which involve believing in people and their abilities; trusting in people to develop goals and deliver on promises; creating opportunities for people to explore their (hi)stories, talents and interests; and instilling into people a sense of identity and personal autonomy. This is embodied well by BSC’s Fenceless Art project at a collective level and the ‘young lady’ who elected to work full-time and independently on it at an individual level. Here, the participation in, and mediation of, creative and cultural activity ‘connect income-generating activities and economic survival with cultural interests and talents’ [54] (p. 69) in the service of the creative economy and local place-based development. This has two broader implications for fruitful, contemporary ACCE work.

Firstly, ACCE practitioners clearly ‘work with communities to ensure that [ACCE] remain[s] inclusive and accountable to the wider community, that [the practitioners] are fair and transparent in their dealings, and that they empower community members to contribute to decision making about the direction of work’ [77] (p. 115). Much of that work is characterised by self-governance and multistakeholder configurations as we have seen. Secondly, the ACCE work we have seen ‘not only [points to] cultural entrepreneurs with economic advantages and/or aesthetic inspiration’, but those entrepreneurs also embody strong ‘moral-political and social values’ [26] (p. 466)—in alignment with the mode of creative and cultural engagement championed by the critical political economy tradition. Here, ACCE work clearly reflects cultural and social entrepreneurship in the sense that alliances of ‘skilled cultural operators’ [80] (p. 64) not only engage in ‘innovative activities and services that are motivated by the goal of meeting a social need’, but also prioritise ‘bringing about improved social outcomes for a particular community or group of stakeholders’ [81] (p. 430, emphasis in original). These ‘operators’ are said to be adept at recognising opportunities to devise and offer novel, effective and valuable solutions to societal problems in ways that market-driven actors and their corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives are unable to [82]. In essence, the former ‘have a cultural focus [that impels them] to address unmet human and social needs’ [81] (p. 442) followed by commercial considerations while the latter tend to foreground profitmaking at the expense of those very social needs.

Second—and as Danny Quinn remarked earlier, ACCE work can be ‘subversive’ which is reflected not only in ‘small rebellions, critical alliances and alternative visions’ [47] (p. 13), but also in ‘micropolitical revolutions’ which ‘help individuals and groups transform the way they engage with the world in the hope of bringing about personal and collective change’ [48] (p. 602). In doing so, ACCE work provides solutions experimented with, explored by and ‘developed through democratic dialogue from within communities themselves’ [51]. Additionally, such work provides not only a means of expressing both an individual and collective relationship to place, but also of enhancing awareness and appreciation of its heritage [21,76,83]. On this basis, then, such work should not be construed merely as the instrumentalisation of local creative and cultural activity intended to plug the holes left by deconstructed welfare services. Instead—and following Perry and Symons [54] (p. 72, italics in original), it should be understood as signalling ‘not culture for community cohesion, but community as culture; not culture for sustainability, but sustainability as culture; not social entrepreneurship for cultural economy; but culture as social entrepreneurship’.

Seen this way, it can be argued that the critical political economy of ACCE is changing largely in favour of the aspirations, interests and needs of communities and publics. ACCE work—though not always smooth and unproblematic as we have seen—helpfully resources and sustains arts and cultural activity within communities and local urban areas in ways that are impactful and meaningful while ensuring durability. Communities, publics and urban locales are enfranchised through empowerment and participation on their own terms. Not only is this achieved through ‘fostering local partnerships among different players to tackle place-specific issues’, but also utilising ‘spatial proximity, trust, face-to-face interaction and the sharing of common resources [to generate] opportunities for [democratic and sustainable] governance that do not exist at larger scales’ [50] (p. 7). This state of affairs casts contemporary ACCE work in a light that suggests such work serves certain elements of the creative economy and local place-based development ventures well in terms of facilitating ‘collaborative, citizen-led interventions that focus on place improvement, community capacity building and economic development, which can in turn feed into a larger strategy or objective’ [61] (pp. 626–627). The ways in which this ‘larger strategy or objective’ conditions, manages and regulates ACCE work needs further critical interrogation.

8.2. ACCE in the Wider Political-Economic Constellation of ‘Disequilibrium and Disorder’

Clearly, the ACCE work under exploration in this article is delivering a broad range of benefits for (and by) communities and local places—including the state, public institutions and corporate business. In doing so, the relations among these different stakeholders point not only to an ability to reconcile (sometimes differing) political, economic, institutional, social and intrinsic expectations and motivations for the benefit of the public good, but also paying particular attention to matters of equity and fairness in the process than has been the case in the past [9,69,70]. The result has been the development of ‘investment strategies and interventions that are more responsive to local needs and demands [and are contributing] to natural organic growth in the vibrancy of [communities], towns and cities [as a result of] bring[ing] together new models of public and private partnership on a regional and city basis’ [1] (p. 16). This leads Beth Perry [74] (p. 128) to predict that ACCE organisations and practitioners are poised to ‘become more significant in contributing to social change in austere times’.

Whilst this is a very important development for the ACCE sector, the downside is that the state and corporate business appear to make use of ACCE ‘as needed by the political and policy [and economic] demands of time and place’ [2] (p. 18). For example, whereas the UK government understands the value of ACCE and has committed to funding it under various state initiatives—including the National Lottery Community Fund that supported the refurbishment of EA’s multimedia bus, local and regional government authorities are tasked with ‘pick[ing] those firms that, with a bit of help, can attract private investment and unlock growth for the future’ [84] (n.p.). In this scenario, ACCE practitioners and their organisations are often sidestepped. For instance, EA is placed at a huge disadvantage when it finds itself having to compete for state subsidy and corporate business support with very well established and powerful arts organisations such as the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust and the Royal Shakespeare Company—both of which are located within walking distance from its community hub, have very long histories and worldwide reputations, and are major drivers of local, regional and national employment and tourism14.

It is fair to contend that these circumstances are borne out of ongoing pressure on public funding and corporate business support caused by persistent austerity. Politics, policy and economics at the macro level increasingly demand of arts and cultural organisations to take ‘risks’ and ‘to become more dynamic [which] may involve organisations changing both their missions and their business models’ [8] (p. 49). Furthermore, such organisations are being required ‘to become more entrepreneurial and develop business models that help them maximise income, reduce costs and become more financially resilient [including] look[ing] for opportunities to share services and explore mergers with other organisations’ [8] (p. 49). This one-size-fits-all approach is deeply problematic because it does not take into consideration the distinctiveness of individual ACCE organisations and the nature of the work they do. The tendency ‘to treat them uniformly [by failing to] take [their] variety [and specific circumstances] into account’ [9] (p. 79) is hugely unhelpful. We saw earlier how EA changed its mission and adopted an entrepreneurial business model—only to be compelled to close its heritage centre because its business plan did not receive full funding. Like EA and BSC, CCA receives state subsidy on a project-by-project basis which—when not forthcoming—leaves the organisation in a very vulnerable position. To be able to operate, ACCE practitioners and their organisations find themselves needing to respond imaginatively to be able to survive—an approach to work in the creative economy that is characterised by high levels of insecurity and precarity [85,86].

While sharing and leveraging community resources with Centre MK is working splendidly for BSC as reflected in ‘the capacity to be economically innovative and creative’ [2] (p. 7) and in exploiting ‘new income streams, marketing [the organisation’s] commercial potential and attracting private investors’ [1] (p. 14), this invariably increases dependence—despite the democratic, meaningful, organic and place-based community participation we saw earlier. Here, community participation and communal enterprise are akin to freelance project work for large corporate business in the creative economy whereby ACCE practitioners and their organisations as well as communities and publics assume responsibility for any emergent risks and failings of commodified cultural engagement in very much the spirit championed by the neoliberal doctrine. In this context, openly critical, emancipatory and overly subversive forms of cultural engagement that pose a real threat to the dominant political, economic and institutional ecosystem through expression of perceived unorthodox and unpopular ideas, narratives and values are much less likely to be tolerated as voices and—what Nolan and Featherstone call—‘spaces of antagonism’ [87] (p. 351). If corporate business, private investors and the state withdraw from partnerships, ACCE work invariably struggles to survive.

To Chris O’Kane, the triad of macro politics, economics and corporate business ‘serve[s] private interests and lead[s] to disequilibrium and disorder’ [41] (p. 688) which engenders ‘periodic crises that call for substantive state intervention’ [41] (p. 690). However, ‘the state intervenes in the name of an illusory common interest that attempts to contain and depoliticise [critical, emancipatory and subversive] struggle [thereby] reproducing capitalist society’ [41] (p. 690). This has a key implication for ACCE work and relations among ACCE practitioners, the communities, publics and urban locales they serve—on the one hand, and stakeholders at the macro and meso levels on the other. Although we have seen that the case studies under examination in this article navigate divergent imperatives mostly successfully, the reproduction of capitalist society and growing influence of associated private interests have been found to pose serious challenges to ACCE work in other national and global contexts as the following commentary offered by Cara Courage neatly captures:

There is tension in some [ACCE] practice claiming both an economic and a community benefit, which may be mutually exclusive. There are also issues of capacity and practice standardisation: there is a danger that the practice becomes the sector’s go-to one-size-fits-all solution to [ACCE], attractive to city authorities in a time of fiscal austerity, appealing to impoverished administrations as an attractive box-ticking and ‘cheap’ solution that acts as a salve to urban realm problems without any structural and meaningful change.[61] (pp. 627–628)

ACCE work in the position described here is misappropriated by dominant hierarchies in politics, policy, established institutions and corporate business to replicate dominant ideologies, modes of engagement and practices that undermine possibilities to mobilise and engage communities, publics and urban locales in critiquing and questioning the current societal order and related austere conditions. This ACCE mode clearly reflects a political economy that remains unchanged because of its disregard for power relations and associated matters of equity, fairness and social justice in the processes of engaging with culture creatively in the interests of the public good. That political economy measures ACCE in predominantly economic terms—seeing it as a series of instrumental ventures in the service of the creative economy and top-down regeneration agendas.

By contrast, the critical political economy of the brand of ACCE that is the subject of this article has shown that cultural engagement is embedded in the daily lives of the case studies and the communities, publics and urban locales they work with. This engagement is characterised by democratic practice, genuine empowerment, meaningful participation, self-governance, equity and fairness, affect and sense of place, and opportunities—all of which offer individual and communal possibilities that are sometimes commodifiable, and at other times less so. To varying degrees, we have seen that ACCE that is centred on equity and fairness enables communities, publics and local places to reclaim some autonomy and control over macro politics, policy and economics that invariably seek to manage, regulate and order cultural engagement based on established ideologies and elitist interests [9,10,18,64]. The understanding is that ACCE work is not driven (at least initially) by turning communities, publics and local places into resources to serve the creative economy per se, but by quotidian routines that contribute to the array of benefits that Andrew Thompson and Arts Council England highlight earlier in the article.

9. Conclusions

We have seen that corporate interest and top-down, policy-driven subsidy can enable but also constrain ACCE. In response to the demands and pressures posed, the ACCE practitioners and organisations under investigation in this article have demonstrated not only ‘an understanding of the changing political economy as both representing new barriers and opportunities for advancing the causes of their organisations’, but also shown remarkable resourcefulness to ‘work in alliances and/or coalitions with other organisations both within and beyond the community’ [50] (pp. 48–49). The brand of ACCE that has emerged is not to be seen as a substitute for withdrawn statutory provision whose task it is to address the perennial structural deprivation afflicting many communities, publics and urban locales. Instead, it should be understood as a truly bottom-up, collectively driven approach to, and hybrid method of, cultural engagement that embraces creativity and new ways of thinking and acting in empowering communities to critically examine their life experiences, to explore new ways of seeing the world, to tap into their potential, and to take responsibility. Its socially transformative power, cultural meaningfulness, ‘moral-political’ significance [26], ‘social and moral’ underpinning [37], positivity and inclination towards self-governance give people more control over many aspects which affect their lives in ways that—to paraphrase Jane Rich’s words—cry out for people to be creative. A critical way in which creativity manifests itself is through the building of cross-sectoral alliances that involve collaboration to achieve individual and collective objectives and outcomes. We have seen that this is realised through (1) recognising appropriate opportunities, and (2) employment of imaginative cultural and social entrepreneurial activities—both of which characterise ‘social actors [that] give rise to new [configurations aimed at] challenging the status quo’ [81] (p. 447).

To resource and sustain operation during these enduring austere and unpredictable times, contemporary communities, publics, local places and practitioners are being compelled to build resilience and iteratively develop ‘their capacity to adopt new tactics in unfavourable situations’ [49] (pp. 35–36). In doing so, ACCE work is drawing on the processes of empowerment and participation [52] and ‘community conscientisation’ [61] that, in tandem, stimulate ‘desire to be involved in culture at a deeper level’ [61] (p. 629). Here, the critical political economy of ACCE is largely working in favour of the aspirations, demands, interests and needs of communities, publics and urban locales—as the ACCE projects we saw earlier in the article demonstrate. This, however, cannot be said of instances where the political economy characterising ACCE fails to pay attention to aspects of equity, fairness and social justice. Although none of the case study organisations provided direct evidence of this, the article draws on very recent studies to argue that macro and meso politics, economics and corporate business misappropriate ACCE to reinforce and maintain the status quo. In such a political, economic and institutional ecosystem, powerful actors ‘abhor the idea of letting citizens [take control of cultural engagement on their own terms because those actors] are absolutely convinced that an elite must decide [and] that [the elites] themselves belong to those chosen few, and that the decisions taken by them are far better than if they were left to the population’ [9] (p. 74). Here, ACCE is essentialised and instrumentalised to give the illusion that cultural engagement is being deployed for truly community and place-based development when, in fact, it is ‘a co-optation of [ACCE] to the agenda of marketisation’ [54] (p. 65). Ultimately, this form of ACCE and its political economy remain unchanged—even in the context of enduring austerity that calls for deeper and more meaningful and sustainable transformations.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Code of Research Conduct and Research Ethics of the University of Nottingham (https://www.nottingham.ac.uk/research/ethics-and-integrity/index.aspx#:~:text=The%20University%20of%20Nottingham’s%20Code,university%2C%20including%20its%20international%20campuses). Approval was neither required nor sought.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | At the time this article went to press, this ethnographic study—which began in May 2013—had examined 35 arts and cultural organisations across England. The examination encompassed participant and non-participant observation, a wide-ranging exploration of numerous documents and artefacts relating to the organisations and the sector, and 45 semi-structured qualitative interviews with sectoral practitioners. |

| 2 | Regulation and associated policy in the UK define a community interest company (CIC) as ‘a special type of limited company which exists to benefit the community rather than private shareholders’. In essence, it is a social enterprise more of which is discussed in the latter sections of this article. See also https://www.gov.uk/set-up-a-social-enterprise (accessed on 13 July 2021). |

| 3 | An inductive approach to the analysis of interview, observational and documentary data was employed. Informed by grounded theory [88], the approach was utilised to pull out and categorise key information and themes, to make connections among them, to pinpoint recurrent connections, to make sense of them, and to offer explanations through formulating argument in Section 7 and Section 8 of this article. |

| 4 | The Arts Council England is an executive non-departmental public body which champions, develops and invests in artistic and cultural experiences to enrich people’s lives. Further information is available here: https://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/arts-council-england (accessed on 17 July 2021). |

| 5 | Table 1 summarises the general features of each of the versions of community engagement in cultural and creative engagement listed. As can be noted, the features blur and overlap in some instances—pointing to fluidity which characterises a continually evolving practice. For specific examples illustrating how the versions operate, see, for instance, [4,5,6,7,11,12,13,14,89]. |

| 6 | For a comprehensive discussion of this era and associated arts and cultural activity, see, for example, [4,5,6]. |

| 7 | Cambridge serves as the administrative capital of the county of Cambridgeshire which comprises five districts—one of which is Fenland. See https://www.britannica.com/place/Cambridgeshire (accessed on 7 March 2022) for more information. |

| 8 | For media coverage of this renovation project, access https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/av/uk-england-coventry-warwickshire-30139255 (accessed on 18 January 2022). |