Understanding South Korea’s Use of Sports Mega-Events for Domestic, Regional and International Soft Power

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Soft Power and Sport in East Asia

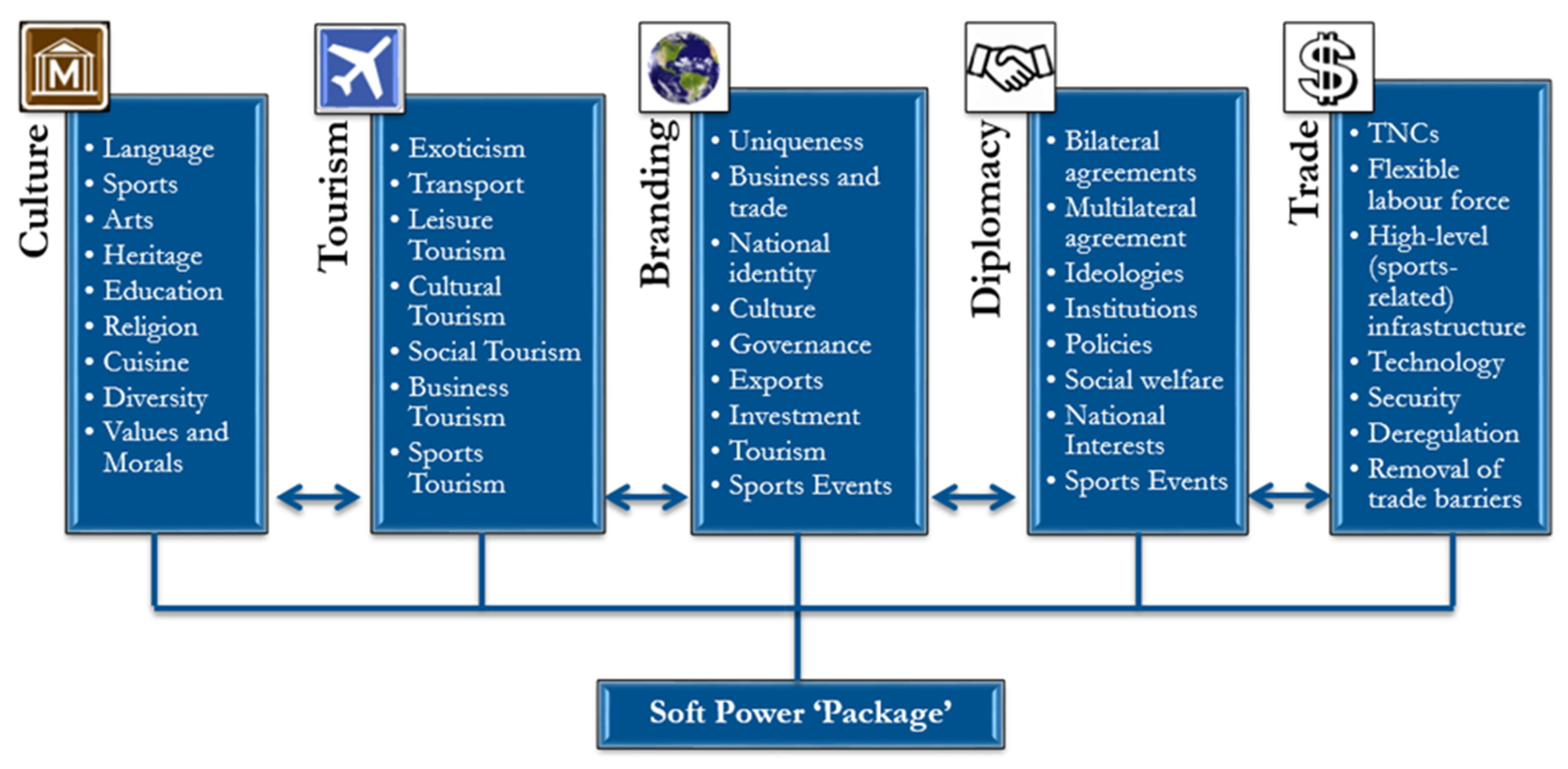

2.2. Understanding ‘Soft Power’

3. Methodology

- National Olympic Committee/National Football Association (representatives and members involved in organising the respective events) (2);

- Government Personnel (involved in organising respective events) (7);

- Sports Industry (1);

- Academic Scholars (3 (focus group)).

4. South Korea’s Use of Sports Mega-Events for Domestic, Regional and International Soft Power

4.1. South Korea’s Rationale behind Hosting the 1988 Seoul Olympics

4.2. South Korea’s Rationale behind Co-Hosting the 2002 FIFA World Cup

2002 FIFA World Cup

Even though hosting the World Cup was right after the Asian financial crisis in 1997, where the economy was getting worse, national morale was down, unemployment was on the rise, it was still the right time for South Korea to host the World Cup in 2002 for recovering from the financial crisis quickly. The citizens believed, with the confidence attained from hosting the 1988 Seoul Olympics, they should be able to host the 2002 World Cup.

Hosting the 2002 World Cup contributed to the rise and emergence of Korea’s Hallyu. In 2001 December 1, in Busan, Korea held the World Cup Group Stage Draw where it would present which nations would play another in slots. While proceeding with this event there were many performances and celebrities. The event was planned with entertainment management companies and professionals in the field of cultural policy.

The World Cup hosting in itself was a huge resource for Korea’s soft power. After hosting the games, many people started to become interested in Korean culture, arts, and what Korea is well known for now, Korean pop-culture. The 2002 World Cup was another chance for the world to see Korea again as much more credible and attractive. Soft power is about being able to attract other people around the world to the nation’s cultural assets. The World Cup was the perfect showcasing of Korea and its soft power assets.

4.3. South Korea’s Rationale behind Hosting the PyeongChang Winter Games, 2018

Gangwon Province is a very remote area, so Gangwon Province has never held a big event like the Olympics. The reason why Gangwon-do tried to host the Olympics three times is because the Olympics can be a catalyst for development in the area. Gangwon Province was hoping for the influx of external capital such as government funds through hosting the PyeongChang Olympics.

The possibility of winning the winter event can be analyzed based on the following two factors. First, based on the principle of circulating to each continent, the 21st (2010) event should be given to the Asian continent, since it has already been held on the other continents: the 18th (1998) Asia (Japan), the 19th (2002) North America (the US) and the 20th (2006) Europe (Italy). Second, Korea is the most promising country to host the winter event given its experience in hosting global mega sporting events and thanks to its weather conditions [81].

I’m the only one person who has worked at both 1988 Seoul Summer Olympics and 2018 PyeongChang 2018 Winter Olympics in KOC. When I went to Sao Paulo for the Seoul Olympics in 1986, no one knew about Korea at that time, but everyone knew about the Seoul Olympics, even though it was two years before the event. Hosting the Seoul Olympics Games was a great moment to let the world know about Korea. By hosting the PyeongChang Games, Korea has become one of the few countries in the world with experience in hosting both the Summer and Winter Olympics, I think this has been an opportunity to further enhance South Korea’s international reputation.

The PyeongChang Olympics Games was a good example of world peace through sport. The diplomatic channel of communication between both Koreas, which started through the participation of North Korea in the PyeongChang Games, restored again and that became the starting point of the inter-Korean summit. It was a great moment between the South and North Korea that the two countries with an armistice have a summit meeting, which discussed a declaration of the end of civil war and a solution to the denuclearization of the Korean peninsula. South and North Korea are hoping to launch a joint bid for co-hosting the 2032 Summer Olympics. The PyeongChang Olympics was a pivotal opportunity to improve inter-Korean relations and the IOC’s role was important from the central government’s perspective.

Through the PyeongChang Olympics, the inter-Korean summit was held three times, and the US-North Korea summit was a success. It was considered a historical moment. In addition, the President of the IOC, Thomas Bach prepared a meeting for the co-host of the 2032 Olympics in Lausanne on 15 February. This can be seen as contributing to peace around world as well as in Northeast Asia, except the relationship between the two Koreas … I think the peaceful mode between the two Koreas at the PyeongChang Olympics served as an opportunity to show the international community the easing of tensions originally caused by the security issues on the Korean peninsular.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Correction Statement

References

- Ikenberry, G.J. The End of Liberal International Order? Int. Aff. 2018, 94, 7–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muggah, R. The Global Liberal Order Is in Trouble—Can It Be Salvaged, or Will It Be Replaced? weforum.org. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2018/04/can-the-global-liberal-order-be-salvaged/ (accessed on 3 June 2021).

- Nye, S.J. Soft Power. Foreign Policy 1990, 80, 153–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roche, M. Mega-Events and Urban Policy. Ann. Tour. Res. 1994, 21, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preuss, H. The Conceptualisation and Measurement of Mega Sport Event Legacies. J. Sport Tour. 2007, 12, 207–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girginov, V. Governance of the London 2012 Olympic Games Legacy. Int. Rev. Sport Sociol. 2012, 47, 543–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leopkey, B.; Milena, M.P. Olympic Games Legacy: From General Benefits to Sustainable Long-Term Legacy. Int. J. Hist. Sport 2012, 29, 924–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalip, L. Towards Social Leverage of Sport Events. J. Sport Tour 2006, 11, 109–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bason, T.; Grix, J. Every Loser Wins: Leveraging ‘Unsuccessful’ Olympic Bids for Positive Benefits. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2020, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grix, J.; Paul, M.B.; Wood, H.; Wynne, C. State Strategies for Leveraging Sports Mega-Events: Unpacking the Concept of ‘Legacy’. Int. J. Sport Policy 2017, 9, 203–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haut, J.; Grix, J.; Brannagan, M.P.; van Hilvoorde, I. International Prestige through ‘Sporting Success’: An Evaluation of the Evidence. Eur. J. Sport Soc. 2017, 14, 311–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.W.; Tan, T.C. The Rise of Sport in the Asia-Pacific Region and a Social Scientific Journey through Asian-Pacific Sport. Sport Soc. 2019, 22, 1319–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grix, J.; Brannagan, M.P. Of Mechanisms and Myths: Conceptualising States ‘Soft Power’ Strategies through Sports Mega-Events. Dipl. Statecr. 2016, 27, 251–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohn, Y. Attracting Neighbors: Soft Power Competition in East Asia. Korean J. Policy Stud. 2011, 26, 77–96. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.W. The Theory and Reality of Soft Power: Practical Approaches in East Asia. In Public Diplomacy and Soft Power in East Asia, 1st ed.; Lee, S., Mellisen, J., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 11–32. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, J. How Nations Use Sport Mega-Events to Leverage Soft Power: A New Rise in East Asia. Ph.D. Thesis, Manchester Metropolitan University, Manchester, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Grix, J.; Brannagan, M.P.; Lee, D. Entering the Global Arena: Emerging States and Sports Mega-Events, 1st ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2019; p. xiii-117. [Google Scholar]

- Tagsold, C. Modernity, Space and National Representation at the Tokyo Olympics 1964. Urban History 2010, 37, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nye, S.J., Jr. Soft Power: The Means to Success in World Politics; Public Affairs: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Black, D. The Symbolic Politics of Sport Mega-Events: 2010 in Comparative Perspective. Politikon 2007, 34, 261–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, S. Asian Soft-Power: Globalization and Regionalism in the East Asia Olympic Games. In Proceedings: International Symposium for Olympic Research; International Centre for Olympic Studies: London, ON, Canada, 2010; pp. 163–177. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Y.; Liu, J. A Comparative Analysis of the Olympic Impact in East Asia: From Japan, South Korea to China. Int. J. Hist. Sport 2011, 28, 2290–2308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangan, J.A.; Kim, H.D.; Cruzc, A.; Kang, G.H. Rivalries: China, Japan and South Korea–Memory, Modernity, Politics, Geopolitics–and Sport. In The Asian Games: Modern Metaphor for The Middle Kingdom Reborn: Political Statement, Cultural Assertion, Social Symbol; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2017; p. 108. [Google Scholar]

- Keohane, O.R.; Nye, S.J., Jr. Power and Interdependence in the Information Age. Foreign Aff. 1998, 77, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattern, B.J. Why Soft Power isn’t so Soft: Representational Force and the Sociolinguistic Construction of Attraction in World Politics. Millenn. J. Int. Stud. 2005, 33, 583–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cull, J.N. The Public Diplomacy of the Modern Olympic Games and China’s Soft Power Strategy. In Owning the Olympics: Narratives of the New China; Price, E.M., Dayan, D., Eds.; The University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2008; pp. 117–144. [Google Scholar]

- Manzenreiter, W. The Beijing Games in the Western Imagination of China: The Weak Power of Soft Power. J. Sport Soc. Issues 2010, 34, 29–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grix, J. The Politics of Sports Mega-Events. Political Insight 2012, 3, 4–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, S.; Pigman, A.G. Mapping the Relationship between International Sport and Diplomacy. Sport Soc. 2014, 17, 1098–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rofe, J.S. Sport and Diplomacy: A Global Diplomacy Framework. Dipl. Statecr. 2016, 27, 212–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G. ‘Friendship First’: China’s Sports Diplomacy during the Cold War. J. Am.-East Asian Relat. 2003, 12, 133–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, F.T.; Sugden, J. The USA and Sporting Diplomacy: Comparing and Contrasting the Cases of Table Tennis with China and Baseball with Cuba in the 1970s. Int. Relat. 2012, 26, 101–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hocking, B. Rethinking the ‘New’ Public Diplomacy. In The New Public Diplomacy; Melissen, J., Ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2005; pp. 28–43. [Google Scholar]

- Kramareva, N.; Grix, J. Understanding Public Diplomacy, Nation Branding, and Soft Power in Showcasing Places via Sports Mega-Events. In Marketing Countries, Places, and Place-Associated Brands; Papadopoulos, N., Cleveland, M., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2021; pp. 298–318. [Google Scholar]

- BBC. Theresa May’s Conservative Conference Speech: Key Quotes. Available online: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-politics-37535527 (accessed on 14 September 2021).

- The Soft Power 30. Portland Communications. Available online: https://softpower30.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/The-Soft-Power-30-Report-2019-1.pdf (accessed on 7 October 2021).

- Watson, I. South Korea’s State-Led Soft Power Strategies: Limits on Inter-Korean Relations. Asian J. Political Sci. 2012, 20, 304–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, L.J. Russia and China Respond to Soft Power: Interpretation and Readaptation of a Western Construct. Politics 2015, 35, 287–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, D.R. Diplomacy and Domestic Politics: The Logic of Two-Level Games. Int. Organ. 1988, 42, 427–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekaran, U. Research Methods of Business: A Skill-Building Approach, 3rd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, C.; Scott, S.; Geddes, A. Snowball Sampling. In The SAGE Encyclopedia of Social Science Research Methods; E-prints; Gloucester University: Cheltenham, UK, 2019; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Kook, R.; Ayelet, S.-H.; Yuval, F. Focus Groups and the Collective Construction of Meaning: Listening to Minority Women. Women’s Stud. Int. Forum 2019, 72, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, M.; Grix, J. Bringing Structures Back in: The ‘Governance Narrative’, the ‘Decentred Approach’and ‘Asymmetrical Network Governance’in the Education and Sport Policy Communities. Public Adm. 2011, 89, 537–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grix, J. The Foundations of Research, 3rd ed.; Red Globe Press: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- IOC. Seoul 1988 Summer Olympics—Athletes, Medals & Results. Available online: https://olympics.com/en/olympic-games/seoul-1988 (accessed on 25 November 2021).

- Kim, S.H. Civil Society and Democratization in South Korea. In Korean Society: Civil Society, Democracy and the State, 2nd ed.; Armstrong, K.C., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2006; pp. 65–84. [Google Scholar]

- Olympedia. Host City Selection. Available online: http://www.olympedia.org/ioc/host_cities (accessed on 25 November 2021).

- Hahm, C. South Korea’s Miraculous Democracy. J. Democr. 2008, 19, 128–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsiaficas, G.; Na, K.C. South Korean Democracy: Legacy of the Gwangju Uprising; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, J.H.; Bairner, A. The Sociocultural Legacy of the 1988 Seoul Olympic Games. Leis. Stud. 2012, 31, 271–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, W.Y. Korea Sports in the 1980s and the Seoul Olympic Games of 1988. Ph.D. Thesis, The Pennsylvania State University, State College, PA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Koh, E. South Korea and the Asian Games: The First Step to the World. Sport Soc. 2005, 8, 468–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, V. Role of Sport in International Relations: National Rebirth and Renewal. Asian Econ. Policy Rev. 2016, 11, 139–155. [Google Scholar]

- Manheim, B.J. Rites of Passage: The 1988 Seoul Olympics as Public Diplomacy. West. Political Quart. 1990, 43, 279–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SOSFO. The History of Seoul Olympic Games XXIVth: Host the Olympic Games; SOSFO Press: Seoul, Korea, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Cha, D.V. Winning Is Not Enough: Sport and Politics in East Asia and Beyond. Int. J. Hist. Sport 2013, 30, 1287–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trunkos, J.; Heere, B. Sport Diplomacy: A Review of How Sports Can Be Used to Improve International Relationships. In Case Studies in Sport Diplomacy; Esherick, C., Baker, R., Jackson, S., Sam, M., Eds.; Fitness Information Technology, Incorporated: Morgantown, WV, USA, 2017; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Moenig, U.; Kim, Y.I. The Early Globalization Process of Taekwondo, from the 1950s to 1971. Int. J. Hist. Sport 2021, 37, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porteux, J.N.; Choi, K.J. Hallyu as Sports Diplomacy and Prestige Building. Cult. Empathy 2018, 1, 70–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.; Houlihan, B. Sport as a Diplomatic Resource: The Case of South Korea, 1970–2017. Int. J. Sport Policy 2021, 13, 45–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J. Why Does Hallyu Matter? The Significance of the Korean Wave in South Korea. Crit. Stud. Telev. 2007, 2, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longman, J. South Korea and Japan Will Share World Cup. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/1996/06/01/sports/soccer-south-korea-and-japan-will-share-world-cup.html (accessed on 30 June 2021).

- McLaughlin, A. Korea/Japan or Japan/Korea? The Saga of Co-hosting the 2002 Soccer World Cup. J. Hist. Sociol. 2001, 14, 481–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugden, J.; Tomlinson, A. FIFA and the Contest for World Football: Who Rules the People’s Game? 1st ed.; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, E. Elite Sport and Nation-Building in South Korea: South Korea as the Dark Horse in Global Elite Sport. Int. J. Hist. Sport 2011, 28, 977–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, O. Getting the Games: Japan, South Korea and the Co-Hosted World Cup. In Japan, Korea and the 2002 World Cup; Horne, J., Manzenreiter, W., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2002; pp. 43–55. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.J. Kim Young-Sam: Politician Who Ended Military Rule in South Korea. Available online: https://www.independent.co.uk/news/obituaries/kim-youngsam-politician-who-ended-decades-of-military-rule-in-south-korea-and-brought-financial-transparency-a6747476.html (accessed on 30 June 2021).

- Kim, S.K.; Finch, J. Living with Rhetoric, Living against Rhetoric: Korean Families and the IMF Economic Crisis. Korean Stud. 2002, 26, 120–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, Y.M.; Bae, Y.; Eva, K.-N. 2002 FIFA World Cup and the Rebranding of South Korea. In Mega-Events and Mega-Ambitions: South Korea’s Rise and the Strategic Use of the Big Four Events; Eva, K.-N., Ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2017; pp. 69–92. [Google Scholar]

- Shim, D. Hybridity and the Rise of Korean Popular Culture in Asia. Media Cult. Soc. 2006, 28, 25–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madichie, N.O. Oppan Gangnam Style! A Series of Accidents–Place Branding, Entrepreneurship and Pop Culture. J. Res. Mark. Entrep. 2020, 23, 103–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billboard. Billboard Global Excl. US Chart. Available online: https://www.billboard.com/charts/billboard-global-excl-us/2021-06-05 (accessed on 29 June 2021).

- Korea Times. Hallyu Resurges in Japan Amid Diplomatic Rift. Available online: https://www.koreatimes.co.kr/www/art/2020/07/398_293277.html (accessed on 30 June 2021).

- Bridges, B. The Seoul Olympics. In The Two Koreas and the Politics of Global Sport; Global Oriental: Kent, UK, 2012; pp. 65–83. [Google Scholar]

- Horne, J.D.; Manzenreiter, W. Accounting for Mega-Events: Forecast and Actual Impacts of the 2002 Football World Cup Finals on the Host Countries Japan/Korea. Int. Rev. Sport Sociol. 2004, 39, 187–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, J.E.; New Index for Korea’s Hallyu. Korea Joongang Daily. Available online: https://koreajoongangdaily.joins.com/2010/03/01/etc/New-index-for-Koreas-hallyu/2917224.html (accessed on 14 September 2021).

- Dong-a Ilbo. Multimedia at the Tip of Hand Its IMT-2000. Available online: https://www.donga.com/en/Search/article/all/20020227/221551/1/Multimedia-at-the-Tip-ofHand%C2%85-%C2%93It%C2%92s-IMT-2000%C2%94 (accessed on 30 June 2021).

- Kim, S.; Nam, C. Hallyu Revisited: Challenges and Opportunities for the South Korean Tourism. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2016, 21, 524–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horne, J. Transnational Sport. Gender, Media, and Global Korea. Sport Soc. 2013, 16, 1218–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merkel, U.; Kim, M. Third Time Lucky!? PyeongChang’s Bid to Host the 2018 Winter Olympics–Politics, Policy and Practice. Int. J. Hist. Sport. 2011, 28, 2365–2383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, C. South Korean President Moon Jae-In Makes One Last Attempt to Heal His Homeland. Available online: https://time.com/6075235/moon-jae-in-south-korea-election/ (accessed on 23 September 2021).

- Merkel, U. The Politics of Sport Diplomacy and Reunification in Divided Korea: One Nation, Two Countries and Three Flags. Int. Rev. Sport Sociol. 2008, 289–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhani, A. Was Hosting the 2018 Winter Olympics Worth the Trouble for South Korea? Available online: https://eu.usatoday.com/story/sports/winter-olympics-2018/2018/02/21/hosting-2018-winter-olympics-worth-trouble-south-korea/350410002/ (accessed on 7 October 2021).

- Wood, J.; Meng, S. The Economic Impacts of the 2018 Winter Olympics. Tour. Econ. 2020, 20, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.M.; Grix, J. Implementing a Sustainability Legacy Strategy: A Case Study of PyeongChang 2018 Winter Olympic Games. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.; Kim, H. Global and Local Intersection of the 2018 PyeongChang Winter Olympics. Int. J. Jpn. Sociol. 2019, 28, 110–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ki, E.J.; Oh, J.; Kim, C.S. Influence of the Olympic Winter Games PyeongChang 2018 on the Korean Wave: Comparison of Perceptions between Koreans and Americans. Int. J. Popul. Stud. 2020, 6, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kietlinski, R. Japan in the Olympics, the Olympics in Japan. Educ. Asia 2016, 21, 35–40. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, M.P. The Pursuit of Regional Geopolitical Aspirations: China’s Bids for the Asian Games and the Asian Winter Games since the 1980s. Int. J. Hist. Sport. 2013, 30, 1048–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, J.H.S. Korea Becomes 5th Nation to Host 4 Major Sporting Events. Available online: https://en.yna.co.kr/view/AEN20180209014000315 (accessed on 10 July 2021).

- You, Y.M. ICT Olympics Will Let Everyone Shine. Available online: https://www.koreatimes.co.kr/www/tech/2017/11/133_239064.html (accessed on 10 July 2021).

- Choi, K.J. The Republic of Korea’s Public Diplomacy Strategy: History and Current Status; USC Center on Public Diplomacy: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Dong-a Ilbo. Peace in Motion Should be Followed along with Olympics. Available online: https://www.donga.com/en/Search/article/all/20180210/1221733/1/Peace-in-Motion-should-be-followed-along-with-Olympics (accessed on 10 July 2021).

- Martínková, I. Pierre de Coubertin’s Vision of the Role of Sport in Peaceful Internationalism. Sport Soc. 2012, 15, 788–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Grix, J.; Jeong, J.B.; Kim, H. Understanding South Korea’s Use of Sports Mega-Events for Domestic, Regional and International Soft Power. Societies 2021, 11, 144. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc11040144

Grix J, Jeong JB, Kim H. Understanding South Korea’s Use of Sports Mega-Events for Domestic, Regional and International Soft Power. Societies. 2021; 11(4):144. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc11040144

Chicago/Turabian StyleGrix, Jonathan, Joonoh Brian Jeong, and Hyungmin Kim. 2021. "Understanding South Korea’s Use of Sports Mega-Events for Domestic, Regional and International Soft Power" Societies 11, no. 4: 144. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc11040144

APA StyleGrix, J., Jeong, J. B., & Kim, H. (2021). Understanding South Korea’s Use of Sports Mega-Events for Domestic, Regional and International Soft Power. Societies, 11(4), 144. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc11040144