Abstract

“Progressive neoliberalism” is the current hegemonic approach to understanding social justice in Western liberal democracies. “Progressive neoliberalism” also resurrects the “deserving” vs. “undeserving” narrative that can lead to punitive and pathologising approaches to poor and unemployed people—the demographic comprising the majority of child and family social work service users. Indeed, research suggests that social workers’ attitudes towards families in poverty are strikingly congruent with “progressive neoliberalism.” This article suggests that generational changes and the particular form of group-based identity, postmodern social justice ideology often taught in social work education have unwittingly conspired to create this concerning picture. This article suggests that the resurrection of radical social work, with attention to economic inequality, is one way to counteract this trend.

1. Introduction

This article traces a relationship between the current Western, hegemonic worldview of social justice [1], the translation of that within child and family social work and the unwitting contribution made by the newer generation of social workers, students and social work education.

The article draws on the ideas of Nancy Fraser, the feminist philosopher who first laid bare the divisions between opposing understandings of the roots of injustice: misrecognition (as proposed by the multiculturalists) and economic maldistribution (as proposed by the social democrats) [2]. Fraser went further than just diagnosing this binary positioning, and attempted to reconstruct the understanding of injustice to incorporate both axes; the “dual perspectival” model of social injustice comprised of both misrecognition and maldistribution [3]. Fraser’s model has been contested, however, most comprehensively by Honneth [4] who suggested that even material inequalities could be interpreted as one expression of legitimate claims for recognition. This article, argues in accord with Fraser, that economic matters are already being obscured by attention to recognition and so the need for a dual-perspectival approach has become increasingly urgent in the current cultural context.

Explaining the model, Fraser [1] (n.p.) states:

Every hegemonic bloc embodies a set of assumptions about what is just and right and what is not. Since at least the mid-twentieth century in the United States and Europe, capitalist hegemony has been forged by combining two different aspects of right and justice—one focused on distribution, the other on recognition. The distributive aspect conveys a view about how society should allocate divisible goods, especially income…. The recognition aspect expresses a sense of how society should apportion respect and esteem, the moral marks of membership and belonging.

Fraser’s two-dimensional model of social (in)justice therefore encompasses attention to misrecognition, or discrimination based on identity features, and to economic maldistribution which can lead to poverty and inequality [3]. Using this foundational framework, the article will explore the current hegemony in the UK, and in the west more generally, and consider how it impacts on social institutions including social work with children and families. The article will also explore how this hegemony allows for a social work practice that can ignore poverty as a legitimate target for social work and/or can recognise poverty as a problem but blame families and attribute primarily behavioural causes to the situation. Finally, the article will consider how social work education should consider its curriculum content in order to avoid exacerbating this type of individualised and blaming approach to practice.

2. Progressive Neoliberalism

Fraser [1] states that the current hegemony in the west is “progressive neoliberalism”. She describes this concept as the alliance between the new mainstream social movements of the cultural left (antiracism, feminism, multiculturalism, LGBTQ+ rights, etc.) where economic matters can be downplayed, and the large civic institutions and corporations that depend on neoliberal economic policy to thrive.

The neoliberal strand of “progressive neoliberalism” is the economic and political ideology that has characterised public and political life since the late 1970s, epitomised by Margaret Thatcher’s government in the UK and Ronald Regan’s in the USA [5]. Neoliberalism, in brief, is the privileging and deregulation of markets and corporations, and the attendant shrinking of the public sphere including cuts to public services and welfare (austerity) [6]. The government role shrinks to a narrow function of making sure conditions are conducive to market functioning and the old social democratic responsibility of the government to ensure the needs of citizens are met, is eroded [5]. De-regulation of industry, of course, means less protection for workers, culminating in zero-hour contracts, very precarious, poorly paid work and a burgeoning group of people known as “the working poor” [7]. Garrett [8] sums up the direct effect of neoliberalism on social work as follows: privatisation of many services such as fostering, residential care and home care; increasing regulation of the workforce; the change in the role of the state as above, meaning less welfare and provision for citizens; precariousness in working conditions; the “new punitiveness” where more prisons and secure accommodation is built (and some privately owned) with containment rather than rehabilitation as the core purpose. According to Garrett, this increase in the punitive state is “the hidden face of the neoliberal model and the necessary counterpart to the restructuring of welfare” [8] (p. 347).

One aspect of neoliberalism that is crucially important to social work is the hegemonic idea of a “moralising self sufficiency discourse” [9] (p. 132). Marston explains that understanding a social problem depends on how it is framed, and if public discourse frames, for example, poverty as a behavioural issue then that is how it will be understood. Cutting welfare benefit makes sense in this framing of poverty. This way of thinking can be illustrated by Margaret Thatcher’s famous claim that there was no real poverty in the UK, instead the problem was behavioural. People do not spend their money responsibly and poverty is, in fact, due to “really hard fundamental character-personality defect” (Margaret Thatcher quoted in Catholic Herald) [10]. From that starting point, a gradual “demonisation” of people in poverty has taken hold in the UK [11], leading to increasingly hardened attitudes to people in poverty [12]. Attitudes softened a little in 2017 towards people with disabilities but remained punitive towards unemployed people with most people believing that unemployed people could easily get a job [13].

The political reorientation to economic neoliberalism and self-sufficiency won over the political right and centre without much difficulty, and in 1997, the New Labour government did not change the neoliberal narrative or policy. In fact, Tony Blair in 1997 inflamed the narrative by stating that “behind the statistics lie households where three generations have never had a job” [14]. When this claim was investigated it was found to be untrue, but it and other such statements took firm root in the public consciousness [14] and confirmed the image of lazy scroungers on the dole.

Therefore, this hugely powerful neoliberal narrative became increasingly ingrained in the minds of the public. Furthermore, as Fraser points out, neoliberal ideas began to be accepted by the political left, who might have resisted more strongly had there not been an appealing narrative based on equality and fairness also in ascendence. In effect, for the neoliberal project to gain further purchase, it had to be seen as “progressive” and congruent with emancipatory objectives. “Only when decked out as progressive could a deeply regressive political economy become the dynamic center of a new hegemonic bloc” [1] (n.p.).

The essential progressive ingredient, then, was drawn from the social movements as already described by Fraser. Disparities in outcomes between different identity groups were highlighted and affirmative action or re-adjustments in salaries or diversity quotas for board rooms, etc., all came to symbolise the new/cultural left and the new fight for equality. What was less apparent, however, was that tackling disparities in outcomes meant that the outcomes themselves were not challenged and were simply regarded as facts of society [15]. For example, the fact that 1% of people own wealth equivalent to the other 99% is an acceptable consequence of “progressive neoliberalism” as long as within that 1%, half are women, and minority ethnic people, disabled people and LGBTQ+ people are represented in their population ratios [15]. The real injustice, that is the fact that 1% own wealth equivalent to that of the other of 99% combined, goes unchallenged. This situation is reflected in calls for pay equality at the BBC of very high earning individuals [16], whilst no-one draws attention to the wages and conditions of the cleaners at the BBC (probably also mainly women).

As Fraser [1] (n.p.) Says:

At the core of this ethos were ideals of “diversity,” women’s “empowerment,” and LGBTQ rights; post-racialism, multiculturalism, and environmentalism. These ideals were…inherently class specific: geared to ensuring that “deserving” individuals from “underrepresented groups” could attain positions and play on a par with the straight white men of their own class... its principal beneficiaries could only be those already in possession of the requisite social, cultural, and economic capital. Everyone else would be stuck in the basement.

The acceptance of “progressive neoliberalism” helps us to understand why, as teachers draw attention to children’s poverty [17], as a UN rapporteur describes the UK as having a “harsh and uncaring ethos” [18], as foodbanks and precarious, poorly paid employment burgeons, and as 8 out of the 10 most struggling groups of school children are on free school meals [19], the political ‘left’ has remined focused on drawing attention to identity group outcome disparities. In “progressive neoliberalism” the neoliberal economic hierarchy and, therefore, poverty is accepted as an ordinary fact of life.

Putting this in terms of Fraser’s two-dimensional model of social justice, it is clear that the recognition strand has come to dominate and that injustices centred on the maldistribution of economic resources have become increasingly obscured:

the rise of “identity politics” …ha(s) conspired to decenter, if not to extinguish, claims for egalitarian redistribution [3].(p. 8, emphasis added)

In essence, the model is currently unbalanced by the hegemonic power of “progressive neoliberalism”.

This section has gone into some detail about the Fraserian concept of “progressive neoliberalism” because it is so significant when it comes to understanding notions of social injustice, the situation of families involved with children’s services and the attitudes of social workers and students to the people they work with—many of whom are “stuck in the basement” [1].

3. Building the Jigsaw

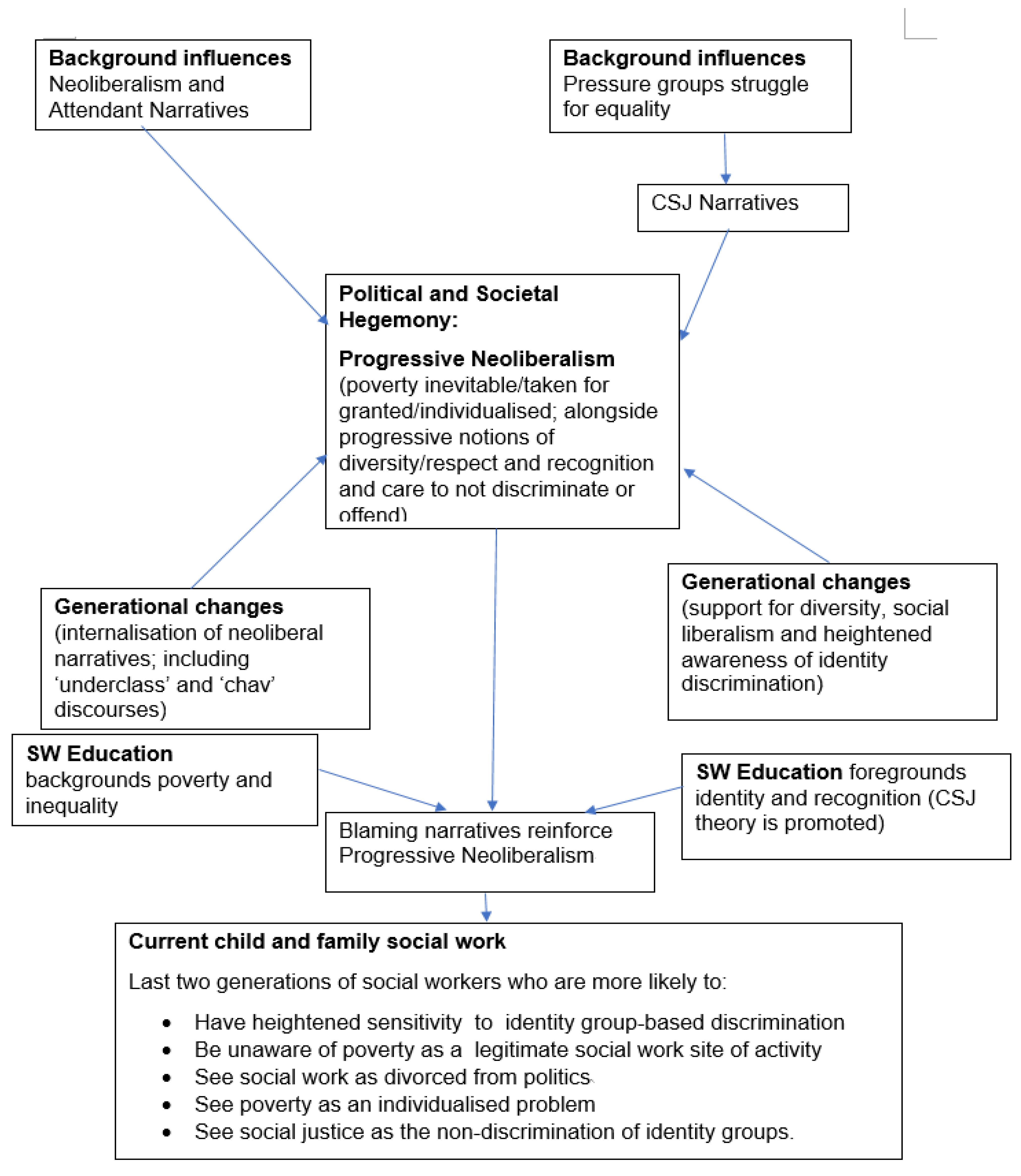

Figure 1 maps the complex factors that give rise to the exacerbation of progressive neoliberalism within social work. The particular neoliberal influences are shown down the left hand side, whereas the “progressive credentials” are illustrated down the right hand side of the diagram.

Figure 1.

Author’s Own Model.

The following section will look at each section of the diagram in turn and explore the relationships between them.

3.1. Background Influences

The background influences under discussion in this section and illustrated by Figure 1, are neoliberalism and attendant narratives (neoliberal influences), and identity pressure groups’ struggles for equality and the resultant rise of postmodern social justice (progressive credentials). Neoliberalism and the attendant narratives have already been discussed in the previous section. The “progressive” strand, however, requires further exploration.

An earlier section introduced how identity pressure groups came to form the activism site for the left of the political spectrum. Originally, groups campaigned for equal rights, such as the civil rights movement for race equality, feminist campaigns for equal rights and, more recently the gay rights movement for equality in terms of equal rights including marriage. These wholly positive developments were very important in reducing the pathologisation of service users within social work [20]. However, these group-based movements have, more recently, further developed their postmodern character and are often referred to as “identity politics” as they are concerned with the recognition of identity features as the political priority [21]. This postmodern framework constructs society as comprised of groups of marginalised people who share an identity feature and are positioned oppressively within social hierarchies [22]. These power differentials have been hardwired into society and the purpose of postmodern critical theory is to look for and find their manifestation in all social interactions and institutions. Therefore, language must be carefully policed and every disparity of group outcome must be assumed to be based on discrimination [23]. To illustrate this, critical race theory (CRT) as the best known of all the postmodern critical theories states that racism in society is ordinary, not aberrational [24] and that white people perpetuate this both consciously and unconsciously as it benefits them to do so [24]. All disparities in group outcome are to be understood as racist, as Kendi [23] (p. 117) in his book How to be an Anti-racist states: “Either racist policies or Black inferiority explains why White people are wealthier, healthier and more powerful than Black people today.” However, the assumption that all group disparities must be caused by discrimination is patently not true and many other reasons can also contribute to disparities such as poverty, age, geography, etc. [19]. This “critical social justice” movement, however, has gained incredible traction over the past decade and its influence can be seen in the acceleration of the roll out of unconscious bias training—rooting out the unconscious perpetuation of those power differentials [25], the BBC spending GBP 100 million on increasing diversity quotas [26], and Universities UK explicitly promoting a response to racism based on critical race theory [27].

For the purposes of this paper, however, it is enough to be aware that group based oppression is the pre-occupation of the media and of many institutions and universities. It has become the default way to think about social justice and comprises the “progressive” aspect of Fraser’s “progressive neoliberalism.”

This section has introduced the background influences that contribute to the current cultural and political hegemony of progressive neoliberalism. The next section looks at how generational changes have further strengthened that ideology (see Figure 1).

3.2. Generational Changes

In a study asking applicants to social work programmes where they attributed causes for social problems, Gilligan [28] found that the “Thatcher’s Children” group (in this study, born 1969–1984) were the group most likely to attribute individual, behavioural causes to social problems. Ten years later, Grasso [29] (p. 30) analysed the British Attitudes Survey from 1985 to 2012 and found that the “millennial” generation (in this study, born 1977–1990) had more “right wing authoritarian” attitudes than any previous generation, and that the patterns were consistent and striking: “Blair’s Babies in particular are almost as negative about benefits and the welfare system as the generation that came of age before it was created”. So, in effect the millennial generation were more likely to believe that benefits made people lazy, that unemployed people could easily get a job if they wanted and that distribution via progressive taxation was not desirable. They were also more authoritarian in their attitudes towards those who had committed crime, poor people and unemployed people (those who could be considered “undeserving” perhaps?). Fenton [30] asked the same questions of 122 “iGeneration” students [31]; the post-millennial generation born from 1995 onwards and our current generation of students. The sample included students from social work, education and community education, and there were no significant differences between social work and the other two discipline groups. The findings demonstrated that iGen students were more “right wing authoritarian” than their older colleagues, many of whom were millennials, on the overall right-wing authoritarian scores and the scores for attitudes to economic inequality and redistribution. They were also more authoritarian than liberal in their attitudes to unemployed people and to those who had broken the law, as were the entire cohort. This is reflective of Grasso’s findings of punitive and authoritarian attitudes to those groups who might be considered “undeserving” and, in fact, tentatively suggests a generational amplification of those attitudes.

The above suggests that the “neoliberalism” aspect of the current hegemony has been significantly internalised by our current generations of students and younger and mid-range social workers. This is demonstrated by clear and consistent beliefs in self-sufficiency, behavioural and individual explanations for poverty and unemployment, and seeing economic re-distribution as a negative. Grasso et al. [29] explain that when younger generations came of age, there was very limited disagreement or debate in the media or in political life about the neoliberal economic and social context. Support for welfare or social democracy had significantly decreased and neoliberalism was taken for granted, unchallenged and hegemonic.

Having said that, support for the UK Labour party is strongest among young people [32] which would appear to confound the above studies’ findings. However, looking at this in economic terms, young people are the group least likely to consider the economy as an important issue [33] and the 18-24 and 25-34 age groups are the least likely to support higher taxes and increased public spending [34]. It might be, then, that the appeal of the “left” is cultural rather than economic, which would be congruent with Grasso et al. [29] and Fenton’s [30] findings. At this point, a cleavage in a traditionally left-leaning political orientation can be detected, with the cultural left, concerned with identity and recognition, possibly uncoupling from the economic left.

Adding evidence for younger generations’ support for culturally left ideas of recognition/identity, it appears that they have stronger values in terms of inclusion and the acceptance of diversity [35] which is very good news for social work values. However, the identity groups included in these notions of diversity—BAME people, LGBTQ+ people, disabled people, women, and transgender people—are, in Nancy Fraser’s words, seen as “deserving” in liberal society, which would again fit completely with neoliberal progressive ideology. In summary, many students support equality for those groups seen as deserving, whilst holding punitive and blaming attitudes to those who might be considered “undeserving”. This is concerning for social work, especially in practice areas where service users might be considered undeserving if viewed through a “progressively neoliberal” lens—poor people, unemployed people, substance misusers and those involved with child protection services. The next section will consider whether social work education is up to the challenge that this presents (see Figure 1).

3.3. Social Work Education

The first point to note is that Cox et al. [36] (p. 35), in a scoping review of social work curricula in six Western democratic countries, found that teaching about poverty and inequality was “backgrounded and not explicitly conceptualized” and that most approaches to social work teaching were based on critical social justice; preoccupied with teaching racism, colonialism, First-nation and postmodern approaches to social justice. As Reed [15] has suggested, this approach leaves the neoliberal economic hierarchy out of the reach of challenge and looks for equality in group outcome within that hierarchy. Research has shown that social work students do find it difficult to apply notions of social justice to their work [37] and it may be difficult for students to understand economic policy and politics and to see the relevance of those things to direct practice with service users. Therefore, it might be unsurprising that an “off the shelf” simplistic framework that identifies notions of misrecognition of various marginalised groups as the bedrock of injustice is appealing.

The problem with the above, apart from it being based on making a priori assumptions about people based on their skin colour, sex or sexual orientation (which could be argued to be anathema to social work and liberal values in general) is, as already mentioned, that understanding social injustice in this way can supplant attention to material circumstances such as poverty and inequality.

There has been recognition of this within the social work literature, with Webb [38] and McLaughlin [39] warning that attention to diversity matters can obscure attention to economic matters and Garrett [8] noting that diversity issues can appear to be completely aligned with social work values when, in fact, the material aspects of injustice are not considered. Garrett [40] actually suggests that as a key practice principle, social work should be wary of identity categories that divide people and supplant attention to class. These objections are not new and Ferguson and Lavalette [20] made the same arguments in 1999, that the real injustice axis—class and material deprivation—is obscured by postmodern preoccupation with group based identity and that this is deleterious to the kind of broad based movement required to mobilise against poverty and exploitation. In sum, these authors warn against a simplistic anti-oppressive-practice understanding of society where there is heightened sensitivity to, and assumptions about, discrimination based on identity features alongside the downgrading of economic and material factors to either invisibility or simply one further identity feature (class). Therefore, although these arguments have been around for a long time in social work, this article suggests that their salience is heightened in the current context of progressive neoliberalism. However, rather than further attention to poverty and inequality in an attempt to rebalance understanding, these issues may be “backgrounded” and social work education may be inadvertently promoting the hegemony of progressive neoliberalism.

Even more concerning is a study by Cooley et al. [41] who found that teaching the critical social justice concept “White privilege” [42] to students who have socially liberal views (as the newer generations of students have as already discussed [35]) actually increased blaming attitudes to poor, white people. The authors suggest that the same effect would probably be apparent in the teaching of, for example, “male privilege” where support for struggling and poor men would diminish. Therefore, those punitive attitudes already exist within the generational cohort, and teaching critical social justice, rather than challenging them, may actually exacerbate them. The authors contend that students feel more punitive towards people who have (white or male) privilege but then fail to take advantage of it. This is completely at odds with what social work education needs to do. It needs to be aware of the generational traits of the newer students and to tackle head-on those individualistic and blaming attitudes rather than inadvertently encourage them.

So far then, the Fraserian concept of “progressive neoliberalism” appears to be the current political and social hegemonic ideology and younger generations of social workers and students appear to hold attitudes congruent with that ideology. Additionally, we have social work education that, when it adopts a critical social justice approach concerned with the oppression of different identity groups, may exacerbate the punitive narrative to “undeserving” groups that progressive neoliberalism entails. In terms of Fraser’s two-dimensional model of social justice, the (mal)distribution aspect of injustice has, indeed been “extinguished” by the dominance of (mis)recognition injustices.

This background is important when contemporary social work practice with families in the child protection system is explored.

3.4. Child and Family Social Work

This brings the article to the last box in Figure 1: current child and family social work.

Rogowski [43] (p. 98) traces the development of children’s social work services from the early 19th Century recognition of child maltreatment through to the contemporary child protection and risk-based service. He states that the “overbearing influence of neoliberalism” should not be underestimated and points out that a belief in free market economics, individualism and self-sufficiency have supplanted the social democratic consensus that governments are responsible for meeting the basic needs of their citizens. Rogowski notes that social democracies favour the public over the private sphere, believe in nationalised industry to protect people from the peaks and troughs of capitalism, believe that governments should strive for egalitarianism, and eschew the market as the unhindered pivot around which society should be arranged. State intervention is considered appropriate to address social inequalities, especially via the welfare system. During the social democratic period, social work with children and families became reasonably well funded, social workers had autonomy and there was an emphasis on preventative and responsive interventions [43].

From 1979, however, the social democratic consensus came under attack from the new right [5]. With the subsequent neoliberal transformation came certain premises that changed the fundamentals of social work including that “the private sector can supply management knowledge and techniques to the public sector, so managerialisation is required” [43] (pp. 100–101). Practitioners have, of course, experienced this overwhelming emphasis on “best value” and on a private-sector ethos which has meant an increase in bureaucracy, performance indicators, processes and procedures rather than autonomy, and a concomitant downgrading of relationship-based practice and welfare or “helping” work [7]. Paralleling this turn from social democracy to neoliberalism was a change in children’s services from welfare to child protection. Although this was recognised in the Munro report [44], little has changed as a result of Munro’s recommendations. Featherstone et al. [45] had suspected this might be the case, due to the wider political context where relationship-based, autonomous work is increasingly difficult in a context characterised by vast inequality, hardship, lack of trust, emphasis on personal responsibility and the erosion of attention to structural factors, advocacy and help. A neoliberal and managerial approach to social work makes sense in that individualised and formal context. The authors also suggest that helping families holistically was undermined by the division in services brought about by “Every Child Matters” between child and adult services, and a construction of parenting based on techniques that could be learned [45] (p. 622). This is illustrated by the increasing practice of “referring on” to parenting skills classes when, as the authors say, the family might be more in need of the price of a loaf of bread.

Therefore, where are we now in terms of child and family social work in the UK? Looking at the final report from the Child Welfare Inequalities Project (CWIP) [46], it seems that not much has changed and that the situation is, if anything, worse in terms of poverty and hardship for children involved with social work. Bywaters et al. [47] found that “these inequalities are very large: children in the most deprived 10% of neighbourhoods in the UK are over 10 times more likely to be subject to an intervention than children in the least deprived 10%” (p. 210). Therefore, the implications of socio-economic circumstances of children remain profound in terms of risk of social work intervention and other deleterious consequences. Of particular relevance to this paper, however, is the finding that in very many cases, social workers did not attempt to address families’ material circumstances when it came to assessment, planning and intervention. The final report of the CWIP stated:

Income, debt, food, heating and clothing, employment and housing conditions were rarely considered relevant risk factors in children’s lives. Poverty has been the “wallpaper of practice”, widely assumed to be ever-present but rarely the direct focus of action by national or local policy makers or senior leaders and managers [46].(p. 53)

At first glance, this looks congruent with the discussion so far, in that the internalisation of progressive neoliberalism would potentially encourage views of service users as “undeserving” and explanations of poverty as resulting from behaviour and individual responsibility. In that case, why would social workers try to help? Instead, they would be likely to focus on behavioural, correctional approaches.

To understand this more fully, the CWIP research group undertook a research study exploring the narratives of social workers [48]. In essence, the findings painted a picture of a social work culture that is over-worked, risk averse, and totally focused on the “core business” of risk assessment and parenting skills/capacity judgements. This core business is divorced from considerations of families’ socio-economic contexts and the culture is inhabited by social workers who are preoccupied with risk factors drawn from notions of the “toxic trio” (mental health, domestic violence and addiction) [48]. Many social workers do not mention poverty or even recognise it as an underlying, structural contributory cause of those more concrete risk factors. Understanding stops at the individual level of explanation and is compounded by beliefs and attitudes based on workers having internalised “underclass” concepts and “chav” narratives. In essence, parents are held responsible for how they react to their poverty and those reactions are the focus of social work effort rather than the poverty itself:

This constellation of factors at times led to a punitive narrative, one that located responsibility for economic and social hardships within the family. Parents were held responsible for developing functional (or non-functional) ways of dealing with their poverty [48].(p. 368)

The findings were further complicated by a well-intentioned attitude on the part of social workers to avoid stigmatising families for their poverty—a finding at odds with the above and leading to what the authors describe as a “moral muddle” [48] (p. 371). Workers wanted to avoid any assumption that poverty automatically meant that poor people were bad parents: “there are plenty of people taking really good care of their children in difficult circumstances” [48] (p. 369). Therefore, social workers did not want to discriminate against parents for being poor, as many do a very good job, but at the same time, parents who failed to deal with their poverty were seen as being personally responsible. Hyslop and Keddell [49] (p. 3) highlight a quote from the then New Zealand Minister of Social Development, the Rt Hon. Paula Bennett, in her foreword to a governmental white paper on vulnerable children, that reflects this attitude:

Though I acknowledge the pressure that financial hardship puts on families, that is never an excuse to neglect, beat, or abuse children. Most people in such circumstances do not abuse their children and I cannot tolerate it being used as a justification to do so.

As Hyslop and Keddell [49] explain, the implication here is that recognising poverty as a significant stressor on families excuses abusive behaviour towards children. The recognition that poverty makes it much harder to parent well (even though many parents do manage that) is deliberately obscured by a narrative that implies only inadequate parents cannot manage their poverty.

Morris et al. [48] also explain that social workers were understanding the situation “through the prism of antioppressive practice” (p.369). This may well be another complicating factor. Poverty (or class) is understood as another identity factor in the antioppressive practice range of characteristics. Thus, social workers resist discriminating against parents for their class/poverty. However, as warned by Ferguson and Lavalette [20] and others, this means that material hardship is relegated to the same status as other possible sources of misrecognition and loses its proper central position in an understanding of injustice—the standalone injustice axis of economic (mal)distribution [3]. To discriminate on the basis of race or gender (misrecognition) is to assume, wrongly, that those identity features are somehow inherently negative in some way. However, material poverty is inherently negative and, although some parents still manage to do well despite that, it is and should be understood as a bad, harmful thing. Social workers need a sophisticated enough capacity for understanding how to differentiate between confidently stating that poverty is a bad thing and a core risk factor and knowing that such a statement is not discriminatory and does not damn all poor parents out of hand.

Once again, however, the above picture highlighted by Morris et al. [48] maps onto Fraser’s [1] concept of “progressive neoliberalism” fuelled by an identity based understanding of social justice or, in social work, a narrow application of antioppressive practice. In order to tackle this, the hegemonic idea that the neoliberal economic hierarchy is just a fact of life and cannot be challenged, must be de-constructed. The effects of it are not simply the “wallpaper of practice” [48] (p. 370) and social workers need to understand how neoliberalism works and how it creates increasing poverty and inequality. They would benefit from understanding that this is how social injustice should be understood and, therefore, why it is a legitimate site for social work intervention.

Additionally concerning, is the internalisation of the “chav” or “underclass” (and “undeserving”) stereotype. Buying into the “moralising self-sufficiency” discourse of neoliberalism [9], is of course part and parcel of the internalisation of “progressive neoliberal” hegemony. Therefore, “lazy scroungers on the dole” and resultant punitive, coercive practice approaches are not surprising. Webb et al. [50] (p. 4) note that white, working class stereotypes of “chavs” can be explained by the belief that:

being both poor and white is frequently constructed as an individual moral failure, an inability to gain socioeconomic status despite the advantages conferred by Whiteness.

This is the exact phenomenon that Cooley et al. [41] demonstrated in their study mentioned previously. Teaching “white privilege” without reference to the broader injustice of economic maldistribution feeds the narrative that poor, white people only have themselves to blame; the “undeserving” narrative in other words.

3.5. Return to Fraser’s Two-Dimensional Model of Social Justice

Fraser’s [3] model of social justice can help understand the situation as set out thus far. If the model was used to understand the plight of the families in Bywaters et al. [47] study, social workers would consider explicitly if these families were struggling with poverty. Where the answer to that is “yes” they would frame this as a social injustice. To do this, they would need knowledge and critical thinking skills about how neoliberal economic policy works, how it has created huge inequalities and further poverty and lack of opportunity for good, valued employment. Then, because of this new “framing” of the problem, they would see poverty as a legitimate and priority issue to tackle.

In terms of recognition issues, if they uncovered an issue of discrimination based on protected characteristics, they would apply Fraser’s test for a recognition “claim”. This is based, not on an imagined moral entitlement to self-esteem drawn from other people, but on an opportunity for everyone to strive for self-esteem under equal conditions. Therefore, a “claim” must rest on evidence of exclusion—in law, policy or practice (for more on this, see Fraser [3]). Fraser’s model, therefore, also facilitates robust action being taken by social work on any issue of (mis)recognition. The point of the model is that one aspect does not overshadow or supplant another—both must be considered. This leads onto the question of how that should be done. Taking action against specific instances of discrimination is more tangible and more likely to be enshrined in complaints procedures, legislation and other processes. Taking action on poverty, however, is perhaps less obvious.

Morris et al. [48] recommend Krumer-Nevo’s [51] poverty aware paradigm (PAP) as an approach that could be rolled out to students and social workers. In ontological terms, the paradigm is based on human rights with an epistemology rooted in critical constructivism—exploring reality as the service user sees it. Whilst there is little to argue with in that construction, Krumer-Nevo critiques both the conservative and structural paradigms of social work for their reliance on positivist knowledge and I would seek to disagree with that. Positivist knowledge is crucial in helping students actually understand poverty and the effects of economic policy, neoliberalism and resultant inequality. Wilkinson and Pickett’s [52] analysis of social problems and inequalities, for example, relies on positivist knowledge, as do patterns of unemployment (to contradict the “long term unemployed being lazy on the dole” narrative) and statistical information about the working poor and other economically disadvantaged groups. Students need this kind of positivist knowledge and understanding to make sense of patterns within society. Fenton’s [7] practice model of radical social work requires student engagement with knowledge and critical thinking about stereotypes and simplistic neoliberal tropes like “work is the way out of poverty.” Without understanding of economic policy, zero hour contracts, the “working poor”, how many families in poverty have at least one adult in work, etc., how can students begin to understand the economic picture and true hardship for people in the UK? Where the PAP and Fenton’s model do converge is in the centrality of relationship-based practice and what Kumer-Nevo terms “relationship based knowledge” [51] (p. 8). There is also convergence between the essential solidarity between service-user and worker, dispensing with the “deserving”/“undeserving” distinction. Fenton’s model requires that the social worker be on the side of the service user and try to help. What will help here? Are there benefit maximisation tasks to be done? Are there other forms of material help that the social worker can access? Can the social worker resist referrals to parenting skills classes or other responses based on a skills deficit, individualising assumption? [7]. Fenton’s model asks workers to explicitly consider the very issues missing from the social work practice summarised in the final report of the CWIP [46], namely: “Income, debt, food, heating and clothing, employment and housing conditions” (p. 5). Some of these actions, or arguing not to refer on, may take moral courage, which is the third action step in Fenton’s model.

Fraser’s two-dimensional model, therefore, elevates poverty to a standalone, priority issue. Understanding social injustice as requiring attention to (mis)recognition and (mal)distribution provides a way out of the moral muddle;—poverty is harmful and negative; understand its political causes and act to alleviate it where possible.

4. Conclusions

As Krumer-Nevo states:

This is a call for social workers to utilise the endless opportunities they have to side with poor people in their Sisyphean struggles with social institutions in cases that are not extreme, and to strive to maintain this position as much as possible in more extreme and challenging cases [51].(p. 11)

These struggles might involve either, or both, of Fraser’s two-dimensional model of injustice — (mal) distribution, leading to poverty and inequality; and/or (mis)recognition, leading to discrimination and exclusion.

To facilitate Krumer-Nevo’s “call”, social work education must face head-on the very significant challenge of helping students, who may well have internalised the current socio-political hegemony of “progressive neoliberalism”, to understand how neoliberalism, working as intended, creates poverty, inequality and hardship. This must involve learning about economics, understanding how poverty itself contributes to more concrete risk factors and, thus, is a priority site for social work activity. Social work education needs to confront this and thus challenge the “undeserving” narrative, or students will continue to become social workers who either do not see poverty as something they should attempt to help with; or blame service users for their own poor circumstances.

Fraser’s model requires that students and social workers think about poverty as an injustice and therefore mitigates against:

- Social workers not “seeing” poverty.

- Social workers not seeing poverty as a site of intervention.

- Social workers understanding poverty only as an individualised and behavioural consequence.

- Recognition or identity features extinguishing attention to material hardship.

- Social workers and students understanding injustice as only a matter of identity features and employing a narrow understanding of antioppressive practice.

The studies from the Child Welfare Inequalities Project surely provide the impetus for some serious rethinking of social work education and the need to foreground questions of economic redistribution. Figure 1 provides an explanation of why social workers may be intervening in the way the studies have highlighted and provides clarity about how social work education might need a reorientation if we do not want to perpetuate, or even exacerbate, the ‘moral muddle’ of current practice.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Fraser, N. From Progressive Neoliberalism to Trump—and Beyond; American Affairs. 2017. Available online: https://americanaffairsjournal.org/2017/11/progressive-neoliberalism-trump-beyond/ (accessed on 1 November 2020).

- Fraser, N. Adding Insult to Injury; Verso: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Fraser, N. Social Justice in the age of identity politics: Redistribution, recognition and participation. In Redistribution or Recognition: A Political-Philosophical Exchange; Fraser, N., Honneth, A., Eds.; Version: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Honneth, A. Redistribution as recognition: A response to Nancy Fraser. In Redistribution or Recognition: A Political-Philosophical Exchange; Fraser, N., Honneth, A., Eds.; Verso: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, I. Reclaiming Social Work: Challenging Neo-Liberalism and Promoting Social Justice; Sage: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Eagleton-Pierce, M. Neoliberalism: The Key Concepts; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Fenton, J. Social Work for Lazy Radicals; MacMillan Higher Ed: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Garrett, P.M. Examining the ‘conservative revolution’: Neoliberalism and social work education. Soc. Work Educ. 2010, 29, 340–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marston, G. Critical discourse analysis. In The New Politics of Social Work; Gray, M., Webb, S.A., Eds.; Palgrave MacMillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Thatcher, M. The Thatcher Philosophy. Catholic Herald. 1978. Available online: http://margaretthatcher.org/document/103793 (accessed on 25 February 2019).

- Jones, O. Chavs: The Demonization of the Working Class; Version: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- JRF (Joseph Rowntree Foundation). Public Attitudes towards Poverty. 2014. Available online: http://www.jrf.org.uk/publications/public-attitudes-towards-poverty (accessed on 24 May 2019).

- British Social Attitudes. Paper Summary: Welfare. 2017. Available online: http://www.bsa.natcen.ac.uk/latest-report/british-social-attitudes-32/welfare.aspx (accessed on 9 March 2020).

- MacDonald, R. The Power of Stupid Ideas: Three Generations That Have Never Worked. 2015. Available online: https://workingclassstudies.wordpress.com/2015/05/11/thepower-ofstupid-ideas-three-generations-that-have-never-worked/ (accessed on 2 October 2019).

- Reed, A. Marx, Race and Neoliberalism. New Labor Forum 2013, 22, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BBC. Carrie Gracie Calls Watchdog’s Report on BBC Equal Pay a “whitewash”. 2020. Available online: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/entertainment-arts-54901308 (accessed on 23 June 2021).

- BBC. Teachers “Need Help” Tackling Poverty Impact on Education. 2018. Available online: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-44295465 (accessed on 20 June 2020).

- UN General Assembly. Visit to the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland: Report of the Special Rapporteur on Extreme Poverty and Human Rights. 2019. Available online: https://undocs.org/A/HRC/41/39/Add.1 (accessed on 5 July 2021).

- Norrie, R. How We Think about Disparity and What We Got Wrong. 2020. Available online: https://civitas.org.uk/content/files/Disparity.pdf (accessed on 5 July 2021).

- Ferguson, I.; Lavalette, M. Social Work, Postmodernism, and Marxism. Eur. J. Soc. Work 1999, 2, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenton, J.; Smith, M. ‘You Can’t Say That!’: Critical Thinking, Identity Politics, and the Social Work Academy. Societies 2019, 9, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pluckrose, H.; Lindsay, J. Cynical Theories: How Universities Made Everything about Race, Gender and Identity; Pitchstone Publishing: Durham, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kendi, I.X. How to Be an Anti-Racist; Bodley-Head: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Delgado, R.; Stefancic, J. Critical Race Theory: An Introduction, 3rd ed.; NYU Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Equality and Diversity UK. Unconscious Bias Training Course. 2019. Available online: https://www.equalityanddiversity.co.uk/unconscious-bias-training-course.htm (accessed on 5 November 2020).

- BBC. BBC Commits £100m to Increasing Diversity on TV. 2020. Available online: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/entertainment-arts-53135022 (accessed on 31 October 2020).

- Universities UK. Tackling Racial Harassment in Higher Education. 2020. Available online: https://www.universitiesuk.ac.uk/policy-and-analysis/reports/Documents/2020/tackling-racial-harassment-in-higher-education.pdf (accessed on 20 May 2021).

- Gilligan, P. Well motivated reformists or nascent radicals: How do applicants to the degree in social work see social problems, their origins and solutions? Br. J. Soc. Work 2007, 37, 735–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grasso, M.T.; Farrall, S.; Gray, E.; Hay, C.; Jennings, W. Thatcher’s children, Blair’s babies, political socialisation and trickle-down value change: An age, period and cohort analysis. Br. J. Pol. Sci. 2017, 49, 17–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenton, J. Taking “Bout iGeneration: A new era of passive-authoritarian social work? Br. J. Soc. Work 2020, 50, 1238–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twenge, J. iGen: Why Today’s Super-Connected Kids Are Growing up Less Rebellious, More Tolerant, Less Happy- and Completely Unprepared for Adulthood; Atria Paperback: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Yougov. How Britain Voted in the 2019 General Election. 2019. Available online: https://yougov.co.uk/topics/politics/articles-reports/2019/12/17/how-britain-voted-2019-general-election (accessed on 13 July 2021).

- Yougov. General Election: Who will Win the Youth Vote? 2019. Available online: https://yougov.co.uk/topics/politics/articles-reports/2019/11/22/general-election-who-will-win-youth-vote (accessed on 13 July 2021).

- NatCen. Backing for More Taxation and Public Spending Falls among Labour Supporters. 2020. Available online: https://natcen.ac.uk/news-media/press-releases/2020/march/backing-for-more-taxation-and-public-spending-falls-among-labour-supporters/ (accessed on 5 July 2021).

- NatCen. British Social Attitudes Reveals Britain Wants Less Nanny State, More Attentive Parent. 2017. Available online: http://www.natcen.ac.uk/news-media/pressreleases/2017/june/british-social-attitudes-reveals-britain-wants-less-nanny-state,-moreattentive-parent/ (accessed on 6 May 2019).

- Cox, D.; Cleak, H.; Bhathal, A.; Brophy, L. Theoretical frameworks in social work education: A scoping review. Soc. Work Edu. 2020, 40, 18–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodward, R.; Mackay, K. Mind the gap! Students’ understanding and application of social work values. Soc. Work. Edu. 2012, 31, 1090–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, S.A. Against diversity and difference in social work: The case of human rights. Int. Soc. Welfare 2009, 18, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, K. Surviving Identity: Vulnerability and the psychology of recognition; Routledge: Hove, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Garrett, P.M. Transcending the Politics of “Difference” and “Diversity”. In Rethinking Anti-Oppressive Theories for Social Work Practice.; Cocker, C., Hafford-Letchfield, T., Eds.; Houndsmill: Palgrave Macmillan, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Cooley, E.; Brown-Iannuzzi, J.L.; Lei, R.F.; Cipolli, W., III. Complex intersections of race and class: Among social liberals, learning about White privilege reduces sympathy, increases blame, and decreases external attributions for White people struggling with poverty. J. Exp. Psy. General. 2019, 148, 2218–2228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DiAngelo, R. White Fragility; Beacon Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Rogowski, S. From child welfare to child protection/safeguarding: A critical practitioner’s view of changing conceptions, policies and practice. Practice 2015, 27, 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munro, E. The Munro Review of Child Protection: Final Report; TSO: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Featherstone, B.; Broadhurst, K.; Holt, K. Thinking systemically –thinking politically: Building strong partnerships with children and families in the context of rising inequality. Br. J. Soc. Work 2012, 42, 618–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- CWIP. The Child Welfare Inequalities Project: Final Report. 2020. Available online: https://pure.hud.ac.uk/ws/files/21398145/CWIP_Final_Report.pdf (accessed on 27 June 2020).

- Bywaters, P.; Scourfield, J.; Jones, C.; Sparks, T.; Elliott, M.; Hooper, J.; McCartan, C.; Shapira, M.; Bunting, L.; Daniel, B. Child welfare inequalities in the four nations of the UK. J. Soc. Work 2020, 20, 193–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, K.; Mason, W.; Bywaters, P.; Featherstone, B.; Brady, G.; Bunting, L.; Hooper, J.; Mirza, N.; Scourfield, J.; Webb, C. Social work, poverty, and child welfare interventions. Child Fam. Soc. Work 2018, 23, 364–372. [Google Scholar]

- Hyslop, I.; Keddell, E. Outing the Elephants: Exploring a New Paradigm for Child Protection Social Work. Soc. Sci. 2018, 7, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, C.; Bywaters, P.; Scourfield, J.; Davidson, G.; Bunting, L. Cuts both ways: Ethnicity, poverty, and the social gradient in child welfare Interventions. Child Youth Serv. Rev. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krumer-Nevo, M. Poverty-aware social work: A paradigm for social work practice with people in poverty. Br. J. Soc. Work 2016, 46, 1793–1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, R.G.; Pickett, K. The Spirit Level: Why Equality is Better for Everyone; Penguin: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).