Abstract

This article asks whether UK universities care about hedgehogs more than they care about people of colour. This absurd question is based on an analysis which shows that UK universities have had much greater engagement with the Hedgehog Friendly Campus initiative than the Race Equality Charter. A comparison with UK universities’ Athena Swan accreditation also highlights that UK universities appear to have taken much more action in tackling gender inequality than racial inequality. This article is purposefully concise to emphasise the need for more action and less discussion in achieving racial equality in UK universities.

1. Introduction

There is a well-established body of academic literature that draws attention to the racism that people of colour1 encounter in UK universities [,,]. This racism often results in people of colour feeling that UK university campuses are hostile spaces that generate a variety of uncomfortable experiences for students and staff. Mirza has explained how this can manifest:

‘[S]tudents of colour are less likely to be admitted to elite ‘Russell group’ universities, even when they have ‘like for like’ entry grades. BME students are to be found mainly in the ‘new’ university sector with its lesser market value, and are less likely than their White counterparts to be awarded a good honours degree or find good jobs commensurate with their qualifications when they graduate. Those who manage to navigate the perilous journey into a career in the Academy disproportionately find themselves on insecure fixed term contracts and lower pay. The most shocking evidence of this ‘crisis of race’ in British higher education, is the dearth of senior Black and Minority Ethnic academics’ [] (p. 4).

The extent of this problem was highlighted in stark terms in a recently published report by the UK’s Equality and Human Rights Commission in which they outlined that, although UK universities often believe that they have tamed racism within their institutions, there is major underreporting of racist incidents, especially in their more common and subtler forms []. The report suggested that the underreporting of racism in UK universities is typically due to a lack of suitable reporting mechanisms, a belief that the complaint will not be taken seriously or a fear of detrimental repercussions for speaking out. For the very few incidents that are reported to UK universities, the report found that universities can take months to resolve them, and in a large number of cases, UK universities do not even uphold the complaint, which may reflect a culture of denial about the pervasiveness and destructiveness of racism within UK academia.

Although it is obvious to many of us that racism continues to manifest in UK universities in a variety of explicit and subtle ways, there are some who remain sceptical about the importance of confronting this issue. For example, some may engage in ‘racist intellectualisation’, where they attempt to justify racial inequality as natural and normal, while others may engage in ‘colour evasion’, whereby they see little reason to talk about racial inequality due to a belief that race does not matter [] (pp. 98-99). In some circles, there is an enthusiastic and unapologetic pushback against anti-racist and decolonial movements which seek to call into question the legacy of colonialism and racism in shaping contemporary UK higher education. These critics dismiss calls to address racism and coloniality in UK universities as little more than an ideological game of identity politics and unpatriotic ungratefulness. However, since the murder of George Floyd in May 2020 and the subsequent global demands for justice that followed, a range of UK institutions, including universities, have articulated a commitment to revisiting the racial inequality that exists within them. Nonetheless, such proclamations have not always been matched with actual change, and others, such as Hall et al., have expressed concerns that the COVID-19 pandemic may have further slowed progress on an already sluggish march toward achieving ‘an anti-racist university’ [] (p. 11).

This article seeks to draw attention to UK universities’ underwhelming commitment to racial equality by offering a somewhat absurd comparison of UK universities’ participation in the Race Equality Charter with their commitment to the Hedgehog Friendly Campus initiative. The results of this unusual comparison suggest that there may be a greater concern for hedgehogs in UK universities than there is for people of colour. While it is admirable that a significant number of UK universities wish to prioritise the conservation of hedgehogs, UK universities must also show an enthusiasm toward achieving racial equality. This article also compares data from Athena Swan to consider how UK universities’ commitment to racial equality compares with their commitment to gender equality. This reveals that UK universities appear to have prioritised the commendable goal of gender equality to a much greater extent than the similarly commendable goal of racial equality. This article is deliberately brief given that priority must be given to more meaningful actions rather than to elaborate discussions about what is already starkly visible.

2. Methodology

According to the Guardian UK Universities League Table 2021, there are 121 universities in the UK2.This article assesses the extent to which these universities have been awarded recognition by the Race Equality Charter and/or the Hedgehog Friendly Campus initiative. The Race Equality Charter is an initiative designed to encourage the success of people of colour in UK higher education. UK universities can apply to the initiative and be granted an award depending on actions taken to address racial inequality. The Hedgehog Friendly Campus initiative is coordinated by the British Hedgehog Preservation Society. It advocates for the protection of hedgehogs on university campuses due to the species being under considerable threat. While there is some ambiguity about when both initiatives were launched, it appears as though the Race Equality Charter emerged in 2015 and that the Hedgehog Friendly Campus initiative emerged in 2019. This article also considers data relating to Athena Swan, an initiative which has existed for more than 15 years and which is designed to promote gender equality in UK higher education. The data used for this article was taken from the relevant websites of the three initiatives3. The comparison that is made is possible because all three initiatives have a similar approach of awarding gold, silver and bronze awards to universities that are able to demonstrate a particular commitment to the respective causes. While the analysis offered in this article is a crude depiction of UK higher education, it nonetheless captures the absurdity of the situation that people of colour may face in UK universities.

3. Findings

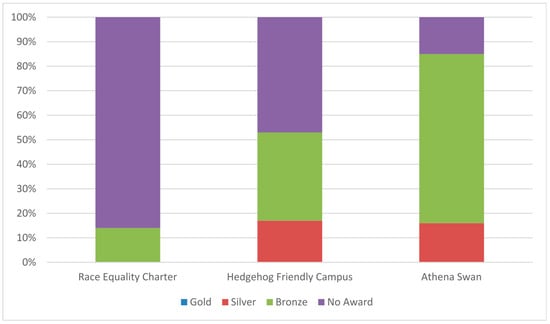

As of June 2021, 17 UK universities hold an award from the Race Equality Charter, 63 UK universities hold an award from the Hedgehog Friendly Campus initiative and 102 hold an award from Athena Swan (see Table 1). No UK universities hold a gold award for any of the three initiatives which is indicative of the fact that no UK universities have achieved racial equality, gender equality or hedgehog protection to the extent that is desired. While no UK universities hold a silver award from the Race Equality Charter, 20 and 19 UK universities hold silver awards from the Hedgehog Friendly Campus initiative and Athena Swan, respectively. There is a greater number of UK universities that hold bronze awards, which includes 17 who hold a bronze award from the Race Equality Charter, 43 who hold a bronze award from the Hedgehog Friendly Campus initiative and 83 who hold a bronze award from Athena Swan. In percentages, this translates to 14% of UK universities holding a Race Equality Charter award, 52% holding a Hedgehog Friendly Campus award and 84% holding an Athena Swan award (see Figure 1). More specifically, while no UK universities hold a silver award from the Race Equality Charter, 17% of UK universities possess a silver award from the Hedgehog Friendly Campus initiative and 16% hold a silver award from Athena Swan. The 14% of UK universities that currently hold a bronze award from the Race Equality Charter is considerably less than the 36% of UK universities who hold a bronze award from the Hedgehog Friendly Campus initiative and drastically less than the 69% of UK universities that hold a bronze award from Athena Swan.

Table 1.

Number of UK universities with gold, silver or bronze awards from the Race Equality Charter, the Hedgehog Friendly Campus initiative, and Athena Swan.

Figure 1.

Percentage of UK universities with gold, silver or bronze awards from the Race Equality Charter, the Hedgehog Friendly Campus initiative, and Athena Swan.

4. Discussion

The findings of this article may be interpreted as suggesting that UK universities care more about hedgehogs than they do about people of colour. This somewhat ridiculous possibility is the case even though the Race Equality Charter appears to have been in existence for several more years than the Hedgehog Friendly Campus initiative. UK universities also appear to have been considerably more successful in promoting gender equality compared to racial equality. While it may be argued that the crude dataset used in this article is unsatisfactory for drawing definitive conclusions, the observations that are made here echo findings from other studies which recognise that UK universities have not taken the Race Equality Charter as seriously as they could have [,] (p. 301, p. 242). This is deeply disconcerting when one considers the large proportion of people of colour who study and work within UK universities.

Further research is required to ascertain why the disparities in awards exist across the three initiatives. For instance, the disparities could be because UK universities have to undertake less stringent actions to be recognised by the Hedgehog Friendly Campus initiative than they do to be recognised by the Race Equality Charter. Moreover, some UK universities may have greater reservations about the Race Equality Charter than they do about the other initiatives, which may be due to a disinterest in racial equality, but could also be due to feeling as though the Race Equality Charter is not the best strategy for attaining racial equality within their institution. Indeed, UK universities may be pursuing their own local race equality initiatives without having much awareness of and/or feeling the need to engage with the Race Equality Charter. Furthermore, there is inadequate data available about the number of UK universities that have attempted, but have not yet been successful, in gaining recognition from the Race Equality Charter, which may portray a different image of the extent to which UK universities are engaging with the Race Equality Charter if it were known. However, until more extensive research is conducted about why there are such significant disparities between UK universities’ engagement with the Race Equality Charter compared to the Hedgehog Friendly Campus initiative and Athena Swan, speculation will continue about whether this is because UK universities are not as committed to racial equality as they should be.

While many would welcome UK universities participating in the Race Equality Charter with greater enthusiasm, it is important to be aware of the limitations of the Race Equality Charter too. Bhopal and Pitkin [] have emphatically argued that, at best, the Race Equality Charter is a superficial ‘tick-box’ exercise which UK universities use as a publicity stunt, and at worse, it is a deliberate effort at preserving existing racial inequality by creating an illusion of change []. In this regard, they argue that people of colour suffer from UK universities’ involvement in the Race Equality Charter firstly because people of colour are often burdened with making the application for an award and secondly because people of colour do not receive any tangible benefits from any awards that are granted. While these criticisms of the Race Equality Charter must be given serious consideration, it may still be better for UK universities to seek an award from the Race Equality Charter rather than not participating in the initiative at all.

5. Conclusions

This article is purposefully brief so as to emphasise that what is required is more action about racial equality in UK academia and less talk about it. More specifically, this article has offered a partly farcical yet still deadly serious provocation which suggests that UK universities appear to be more enthusiastic about protecting hedgehogs than they are about protecting people of colour. UK universities also appear to have taken considerably more action in tackling gender inequality than in tackling racial inequality. Going forward, the senior leadership teams of UK universities must ask themselves if they are investing enough resources into protecting and empowering people of colour within their campuses. The Race Equality Charter may be a helpful framework to assist them in this endeavour. What must be made clear though is that increasing the number of people of colour within UK higher education is insufficient, but rather, as Abdulrahman et al. have argued, what is needed is access to an academic environment that values and empowers all members of the university, including people of colour, to avoid subjecting people of colour to hostile environments that result in more pain than nourishment []. While individual staff members who work in UK universities may not have the authority to apply to the Race Equality Charter on behalf of their institution, they could still lobby key management personnel in their institutions for greater action towards achieving racial equality, perhaps after checking which awards their own institution currently holds. At a national level, consideration could also be given as to whether the UK government should mandate UK universities to proactively commit to minimum standards before certain funding and statuses are afforded to UK universities.

It is important to stress that UK universities do not only need to address racial equality but also that they could and should do more in the pursuit of hedgehog preservation and gender equality too. Furthermore, it must be emphasised that the quest for racial equality does not need to come at the expense of hedgehog preservation or gender equality. Indeed, while UK universities appear to have had more success in the Hedgehog Friendly Campus initiative and Athena Swan compared to the Race Equality Charter, there is still much that UK universities could do with respect to these two noble causes too. An intersectional approach would also alert us to the fact that there can be no racial equality without gender equality and vice versa. Thus, it must be stressed that this article does not call for the de-prioritisation of efforts at attaining gender equality or hedgehog preservation but, rather, calls for the enthusiastic pursuit of multiple initiatives that transform UK universities into more inclusive spaces.

It would be beneficial for a longitudinal audit to be conducted to review the data discussed in this article to ascertain whether progress is being made in relation to the laudable causes of racial equality, gender equality and hedgehog preservation. Future research may also extend the comparisons to other initiatives to which UK universities may subscribe, such as those that relate to equality for disability, sexuality and so on. It is crucially important that future research seeks to offer a much richer account than has been offered in this article about the qualitative reasons why UK universities do or do not engage with initiatives such as the Race Equality Charter and, perhaps more importantly, what consequences this engagement, or lack of engagement, has for people of colour within UK universities. This may be more productive if undertaken at the institutional rather than the national level. As we continue the conversation, recognising the absurdity of the world we live in may finally jolt us to opening our eyes to the ridiculousness of our inaction at addressing racial inequality.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available datasets were analysed in this study. The data can be found here: The Race Equality Charter award details can be found here: https://www.advance-he.ac.uk/equality-charters/race-equality-charter/members accessed on 5 July 2021. The Hedgehog Friendly Campus award details can be found here: https://www.britishhedgehogs.org.uk/hedgehog-friendly campus-awards-announced/ accessed on 5 July 2021. The Athena Swan award details can be found here: https://www.advance-he.ac.uk/equality-charters/athena-swan-charter/participants-and-award-holders accessed on 5 July 2021.

Conflicts of Interest

The author professes a fondness for hedgehogs and a passion for equality but declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | ‘People of colour’ are individuals and groups who may be subject to structural and everyday racism on account of being racialised as non-white in a system where sociohistorical forces have constructed whiteness as a hegemonic and superior signifier. These individuals and groups are sometimes referred to with alternative terms such as BAME people, non-white people, ethnic minorities, postcolonial people and the global majority. While each term has its own specific limitations, all of these terms, including ‘people of colour’, share the limitation of ontologically totalising diverse communities of individuals into a singular group, which not only prioritises racial identity at the expense of other aspects of identity (such as class, gender, etc.) but may also give the misleading impression that people of colour are homogenous. It is important to stress that there is much diversity amongst people of colour, including in their experiences and in the way that they perceive and relate to one another. |

| 2 | The relevant data can be found here: https://www.theguardian.com/education/ng-interactive/2020/sep/05/the-best-uk-universities-2021-league-table accessed on 5 July 2021. |

| 3 | The Race Equality Charter award details can be found here: https://www.advance-he.ac.uk/equality-charters/race-equality-charter/members. The Hedgehog Friendly Campus award details can be found here: https://www.britishhedgehogs.org.uk/hedgehog-friendly campus-awards-announced/ accessed on 5 July 2021. The Athena Swan award details can be found here: https://www.advance-he.ac.uk/equality-charters/athena-swan-charter/participants-and-award-holders accessed on 5 July 2021. |

References

- Johnson, A. Throwing Our Bodies Against the White Background of Academia. Area 2020, 52, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph-Salisbury, R. Institutionalised Whiteness, Racial Microaggressions and Black Bodies Out of Place in Higher Education. Whiteness Educ. 2019, 4, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moosavi, L. The Myth of Academic Tolerance: The Stigmatisation of East Asian Students in Western Higher Education. Asian Ethnicity 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirza, H.S. Racism in Higher Education: ‘What Then, Can Be Done?’. In Dismantling Race in Higher Education: Racism, Whiteness and Decolonising the Academy; Arday, J., Mirza, H.S., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 3–23. [Google Scholar]

- EHRC. Racial Harassment Inquiry: Survey of Universities; Equality and Human Rights Commission: Manchester, UK, 2019; pp. 1–113. [Google Scholar]

- Gillborn, D. We Need to Talk about White People. Multicult. Perspect. 2019, 21, 97–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, R.; Ansley, L.; Connolly, P.; Loonat, S.; Patel, K.; Whitham, B. Struggling for the Anti-Racist University: Learning from an Institution-Wide Response to Curriculum Decolonisation. Teach. High. Educ. Crit. Perspect. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arday, J.; Belluigi, D.Z.; Thomas, D. Attempting to Break the Chain: Reimaging Inclusive Pedagogy and Decolonising the Curriculum within the Academy. Educ. Philos. Theory 2020, 53, 298–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doharty, N.; Madriaga, M.; Joseph-Salisbury, R. The University Went to ‘Decolonise’ And All They Brought Back Was Lousy Diversity Double-Speak! Critical Race Counter-Stories from Faculty of Colour in ‘Decolonial’ Times. Educ. Philos. Theory 2021, 53, 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhambra, G.K.; Nişancıoğlu, K.; Gebrial, D. Decolonising the University in 2020. Identities Glob. Stud. Cult. Power 2020, 27, 509–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhopal, K.; Pitkin, C. ‘Same Old Story, Just a Different Policy’: Race and Policy Making in Higher Education in the UK. Race Ethn. Educ. 2020, 23, 530–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulrahman, H.K.; Adebisi, F.; Nwako, Z.; Walton, E. Revisiting (Inclusive) Education in the Postcolony. J. Br. Acad. 2021, 9, 47–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).