Social Role Narrative of Disabled Artists and Both Their Work in General and in Relation to Science and Technology

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Role and Impact of Artists

1.2. Science and Technology: One Area of Engagement for Artists

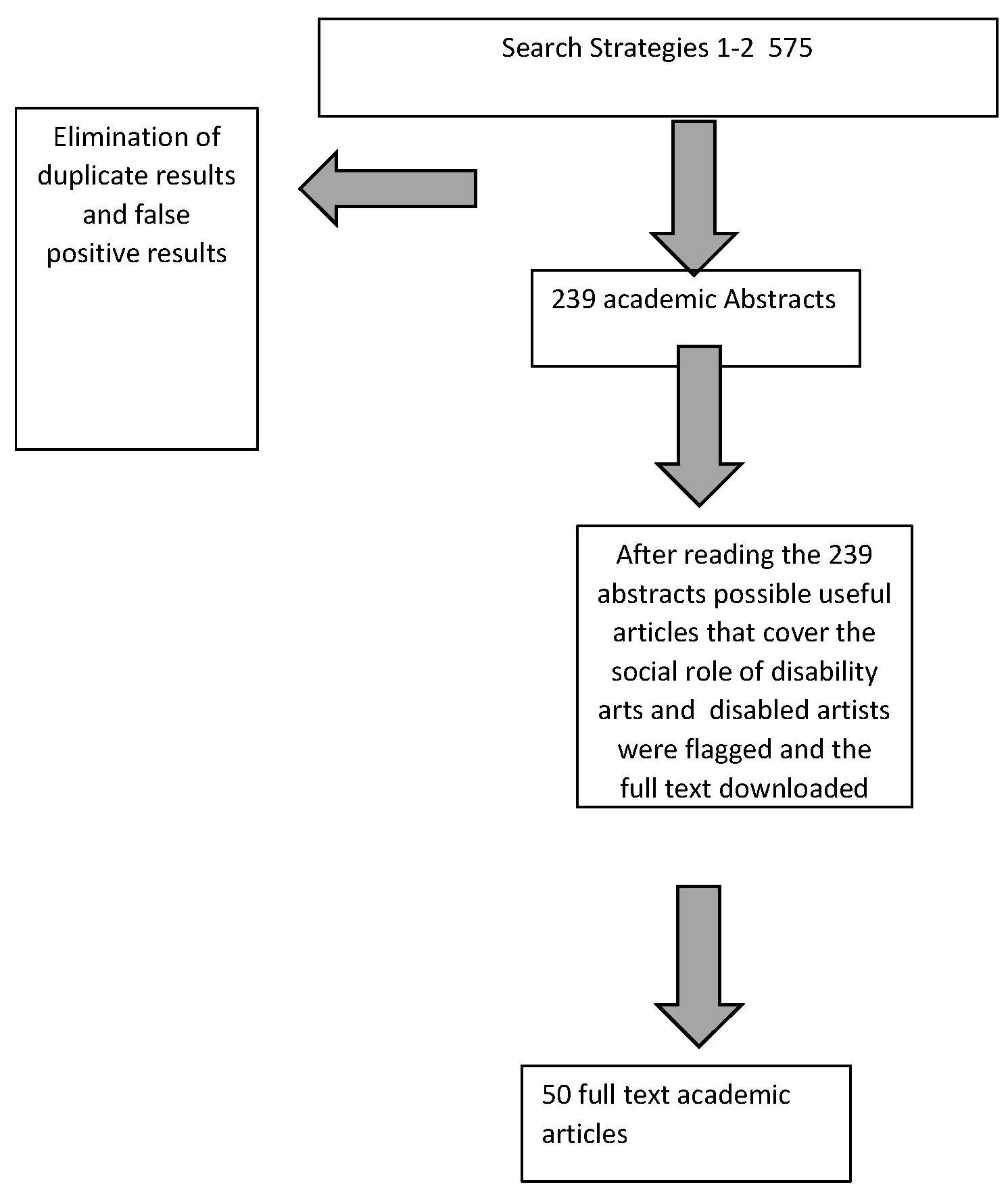

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Identification of Research Questions

2.2. Data Sources and Data Collection

2.3. Data Analysis

2.4. Trustworthiness Measures

2.5. Limitations

3. Results

3.1. Disabled Artists and Their Work: The Social Role of “Disability Art(s)”

“The disability arts movement is increasingly becoming the focus of the mounting of these challenges (against dominant disablist imagery), but it has, itself, had to struggle to free itself from the domination of able- bodied professionals who tended to stress art as therapy (Lord 1981) rather than art as cultural imagery. That, too, is changing as disabled people struggle to take control of their lives” [206] (p. 133).

3.2. Disabled Artists and Their Work: The Social Role of Disabled Artists

3.3. Disabled Artists and Technologies

3.4. Disabled Artists and Museums

“Ann: Can you each tell me a bit about what you are working on these days, especially as regards disability art and culture? Joan: I’m working on many things with respect to performance and civic engagement. Climate change. Immigration. Racial justice. Gun violence. And all this also has implications around disability because we live in an intersectional world. But as regards disability more specifically, our DisAbility Project continues to perform and advocate. We are one of the oldest projects in the U.S. with over two decades under our collective belt, and are included in the collection of the Missouri History Museum. Somewhat incredibly to me, we have performed for over 100,000 people, many of whom are students, thus influencing generations of potential change agents. As writer Kenny Fries says, “Cultural access is as essential as physical access to an inclusive society” (“Access for All”)” [190] (p. 232).

4. Discussion

4.1. Opportunities Based on Existing Role Narratives Concerning Artists and the Arts

4.2. Opportunity to Expand the Role of Disabled Artists and Arts in Science and Technology Governance

“When I tell people I am a cyborg, they often ask if I have read Donna Haraway’s ‘A Cyborg Manifesto’. Of course, I have read it. And I disagree with it” and “The manifesto coopts cyborg identity while eliminating reference to disabled people on which the notion of the cyborg is premised. Disabled people who use tech to live are cyborgs. Our lives are not metaphors” and “It can be a bit intimidating to claim cyborg identity. I feel like it is an impossible task to define myself against the cyborg wreckage of the last century while placing myself in the present and projecting forward. I worry that the cyborg is sometimes just a sexy way to say, ‘Please care about the disabled,’ and why should I have to say that? I worry that the cyborg is too much an institution, an illusion of the nondisabled, the superhero in the movie, the mixed martial artist, the bots who either make life easy or ruin everything. Yet I recognize the disabled who double as cyborgs” [251] (see also Young on cyborgism [252]).

4.3. Opportunities Based on the Existing Roles of Museums

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Knežević, J. The social role of art and the artist in the ballads of Günter Grass and Wolf Biermann. Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 2014, 5, 257–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mardirosian, G.H.; Belson, S.I.; Lewis, Y.P. Arts-based Teaching: A Pedagogy of Imagination and a Conduit to a Socially Just Education. Curr. Issues Educ. 2009, 12, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Carruthers, B. Art, sweet art. Altern. J. 2006, 32, 24–27. [Google Scholar]

- Magaš, L.; Prelog, P. George Grosz and Croatian art between the two world wars. RIHA J. 2011, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novy, J.; Colomb, C. Struggling for the right to the (creative) city in berlin and Hamburg: New urban social movements, new ‘spaces of hope’? Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2013, 37, 1816–1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehrhardt, M.; Steele, S. Frederick Coates: First World War ‘facial architect’. J. War Cult. Stud. 2017, 10, 7–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mistry, J.; Andrew, D. Pedagogies and practices of disaffection: Film programmes in arts schools in a time of revolution. J. Afr. Cine. 2017, 9, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frenette, A. The Rise of Creative Placemaking: Cross-Sector Collaboration as Cultural Policy in the United States. J. Arts Manag. Law Soc. 2017, 47, 333–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegenthaler, F. To Embrace or to contest urban regeneration? Ambiguities of artistic and social practice in Contemporary Johannesburg. Transcult. Stud. 2017, 8, 7–39. [Google Scholar]

- Vahtrapuu, A. The role of artists in urban regeneration processes: A sensory approach of the city. Territ. Mouv. 2013, 10, 103–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ley, D. Artists, aestheticisation and the field of gentrification. Urban Stud. 2003, 40, 2527–2544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aalbers, M.B.; Sabat, M. Re-making a Landscape of Prostitution: The Amsterdam Red Light District: Introduction. City 2012, 16, 112–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banyas, R. The transit landscape. Public Art Rev. 2002, 13, 10–16. [Google Scholar]

- Blanc, N.; Benish, B.L. Form, Art and the Environment: Engaging in Sustainability; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 1–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jost, J.T.; Kay, A.C.; Thorisdottir, H. Social and Psychological Bases of Ideology and System Justification; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2009; pp. 1–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varutti, M. Crafting heritage: Artisans and the making of Indigenous heritage in contemporary Taiwan. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2015, 21, 1036–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, S. ‘And did those feet’? Blake and the role of the artist in post-war Britain. In Blake 2.0: William Blake in Twentieth-Century Art, Music and Culture; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2012; pp. 149–161. [Google Scholar]

- Galvan, T. Interview: “Education should be the antithesis to genocide:” Gint Aras Reckons with the Burdens of History. Available online: https://thirdcoastreview.com/2020/01/12/education-should-be-the-antithesis-to-genocide-gint-aras-reckons-with-the-burdens-of-history/ (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- Brown, J.S. Art and Innovation: The Xerox PARC Artist-in-Residence Program; MIT Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- World Academy of Art and Science. Overview. Available online: http://www.worldacademy.org/content/overview (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- Wilson, S. Information Arts: Intersections of Art, Science, and Technology; MIT Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Sandin, D.J.; DeFanti, T.; Kauffman, L.; Spielmann, Y. The Artist and the Scientific Research Environment. Leonardo 2006, 39, 219–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grey, M.; Norris, L.G. ArtScape: Creating an Artist-In-Residence Program at the Joggins Fossil Institute, Nova Scotia, Canada, to Engage the Public with Earth Sciences. Available online: http://archives.datapages.com/data/atlantic-geology-journal/data/055/055001/pdfs/405.htm (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- Fannin, M.; Connor, K.; Roden, D.; Meacham, D. BrisSynBio Art-Science Dossier. NanoEthics 2020, 14, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roughley, M.; Smith, K.; Wilkinson, C. Investigating new areas of art-science practice-based research with the MA Art in Science programme at Liverpool School of Art and Design. High. Educ. Pedagog. 2019, 4, 226–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, S.J. The Artist as Model User: Reflections on Creating with a Quantified Self. In Proceedings of the 2019 on Creativity and Cognition; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 163–172. [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann, B. Linking Science and Technology with Arts and the Next Generation—The Experimental Artist Residency “STEAM Imaging”. Leonardo 2021, 54, 185–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronwen, W.-L.; Jessica, V.; Melissa, S. Explainer: What’s the Difference between STEM and STEAM? Available online: https://theconversation.com/explainer-whats-the-difference-between-stem-and-steam-95713 (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- Villanueva Baselga, S.; Marimon Garrido, O.; González Burón, H. Drama-Based Activities for STEM Education: Encouraging Scientific Aspirations and Debunking Stereotypes in Secondary School Students in Spain and the UK. RScEd 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, S. Art as a Pathway to Scientific Awareness and Action: Leveraging Art to Communicate Science and Engage Local Communities for the National Estuarine Research Reserve System; Nicholas School of the Environment, Duke University: Durham, NC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, G. Are artists the new interpreters of scientific innovation. New York Times, 12 September 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, S. The Lost Map of Matteo de’ Pasti: Cartography, Diplomacy, and Espionage in the Renaissance Adriatic. J. Early Mod. Hist. 2016, 20, 19–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak-Leonard, J.; Skaggs, R. Public Perceptions of Artists in Communities: A Sign of Changing Times. Artivate 2017, 6, 5–22. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon-Nesbitt, R. The culture of capital. Critique 2009, 37, 553–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ultan, L. Crises in society: The role of the arts. (cover story). Des. Arts Educ. 1989, 90, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woddis, J. Arts practitioners in the cultural policy process: Spear-carriers or speaking parts? Int. J. Cult. Policy 2014, 20, 496–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garvis, S.; Pendergast, D. An Investigation of Early Childhood Teacher Self-Efficacy Beliefs in the Teaching of Arts Education. Available online: http://www.ijea.org/v12n9/v12n9.pdf (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- Nisbett, M. The art of attraction: Soft power and the UK’s role in the world. Cult. Trends 2015, 24, 183–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villarrubia-Mendoza, J.; Vélez-Vélez, R. Iconoclastic Dreams: Interpreting Art in the DREAMers Movement. Sociol. Q. 2017, 58, 350–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wetselaar, R.S. Social location, mobilization and globalization: The role of art in creating social change in Hamilton, Ontario. Int. J. Incl. Mus. 2008, 1, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finley, S. Ecoaesthetics: Green arts at the intersection of education and social transformation. Cult. Stud. Crit. Methodol. 2011, 11, 306–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simić, O.; Volčič, Z. Transitional Justice and Civil Society in the Balkans; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 1–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulmer, J.B. Writing Urban Space: Street Art, Democracy, and Photographic Cartography. Cult. Stud. Crit. Methodol. 2017, 17, 491–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Fallon, D. Arts Opens Many Doors. Am. Music Teach. 2000, 50, 70. [Google Scholar]

- Giraldo, E. Artistic boundaries in baldomero sanín cano’s essays on art and aesthetics. Aisthesis 2015, 58, 145–171. [Google Scholar]

- Zander, M.J. Murals as Documents of Social History1. Art Educ. 2004, 57, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathews, V. Artcetera: Narrativising gentrification in Yorkville, Toronto. Urban Stud. 2008, 45, 2849–2876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, S.; Coaffee, J. Art, gentrification and regeneraton—From artist as pioneer to public arts. Eur. J. Hous. Pollicy 2005, 5, 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahbarianyazd, R.; Doratli, N. Assessing the contribution of cultural agglomeration in urban regeneration through developing cultural strategies. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2017, 25, 1714–1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKay, I. “... by our echoes we chart a new geography”. Geogr. Mag. 1989, 61, 34–38. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins, N. A new outlook for rehabilitation: Creative art therapy. Caring Natl. Assoc. Home Care Mag. 1993, 12, 80–84. [Google Scholar]

- Dal Farra, R. Can the Arts Help to Save the World? Leonardo 2013, 46, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauesen, L.M. The role of the (Governance of the) arts in cultural sustainability: A case study of music. In Developments in Corporate Governance and Responsibility; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2016; Volume 9, pp. 49–74. [Google Scholar]

- Roupakia, L.E. “Art-iculating” affective citizenship: Dionne brand’s what we all long for. Atlantis 2015, 37, 31–50. [Google Scholar]

- Carman, J. Arts and Crafts and Reconstruction. Soc. Dyn. 2004, 30, 114–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mytum, H. Evoking time and place in reconstruction and display: The case of celtic identity and iron age art. In Ancient Muses: Archaeology and the Arts; The University of Alabama Press: Tuscaloosa, AL, USA, 2003; pp. 92–108. [Google Scholar]

- Skybreak, A. Some Ideas on the Social Role of Art. Available online: https://revcom.us/a/v23/1110-19/1114/skybreak_art.htm (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- Herbut, A. Having a Voice—Anka Herbut. Available online: https://en.mocak.pl/having-a-voice-anka-herbut (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- Purnell, P. A Place for the Arts: The Past, the Present and Teacher Perceptions. Teach. Artist J. 2004, 2, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baur, P.W. Analysing the impact of BREXIT on artists careers within the United Kingdom by examining the market for ‘fine art’. Afr. J. Hosp. Tour. Leis. 2019, 8, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Deans, J.; Brown, R. Reflection, renewal and relationship building: An ongoing journey in early childhood arts education. Contemp. Issues Early Child. 2008, 9, 339–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breckenridge, J. Text and the city: Design(at)ing post-dictatorship memorial sites in Buenos Aires. In Latin American Jewish Cultural Production; Vanderbilt University Press: Nashville, TN, USA, 2009; pp. 135–154. [Google Scholar]

- Vukadin, A.; Wongkitrungrueng, A.; Assarut, N. When art meets mall: Impact on shopper responses. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2018, 27, 277–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, P.M. Re-accessing the Power of Art in the Discipline of Pan-African Studies. J. Pan Afr. Stud. 2014, 7, 99–117. [Google Scholar]

- Pearson, H.E. Moving towards the trialectics of space, disability, and intersectionality: Intersecting spatiality and arts-based visual methodologies. Knowl. Cult. 2017, 5, 43–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuttner, P.J. Educating for Cultural Citizenship: Reframing the Goals of Arts Education. Curric. Inq. 2015, 45, 69–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H. Practicing social work through fiction-writing and journalism: Stories from Vietnam. Int. J. Innov. Creat. Chang. 2015, 2, 100–116. [Google Scholar]

- Ramsey, P. Arts and Older People Strategy 2010–2013, Arts Council of Northern Ireland. Cult. Trends 2013, 22, 270–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, T.; Hyater-Adams, S.; Hinko, K.; Fracchiolla, C.; Nordstrom, K.; Finkelstein, N. The intersection of identity and performing arts for black physicists. In Proceedings of the Physics Education Research Conference, Washington, DC, USA, 1–2 August 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balint, T.S.; Pangaro, P. Design space for space design: Dialogs through boundary objects at the intersections of art, design, science, and engineering. Acta Astronaut. 2017, 134, 41–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, H.; Donnellan, C.; O’Neill, D. A review of qualitative methodologies used to explore patient perceptions of arts and healthcare. Med. Humanit. 2012, 38, 106–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eades, G.; Ager, J. Time being: Difficulties in integrating arts in health. J. R. Soc. Promot. Health 2008, 128, 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, M.K.; Singh, P.; Klopfenstein, K.; Henry, T. Access to high school arts education: Why student participation matters as much as course availability. Educ. Policy Anal. Arch. 2013, 21, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Tsoupikova, D.; Kostis, H.N.; Khare, M. A practical guide to art/science collaborations. In Proceedings of the ACM Siggraph 2013 Courses, Anaheim, CA, USA, 21–25 July 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Pagliarini, L.; Locardi, C.; Vucic, V. Toward alive art. In Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Heudin, J.C., Ed.; Virtual Worlds, VW 2000; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, 2000; Volume 1834, pp. 171–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laranjeira, D.H.P.; Iriart, M.F.; Luedy, E. Art as politics of resistance: Cartographic devices in the apprehension of youth cultural practices in the northeast of Brazil. Etnografica 2018, 22, 427–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walhout, M.; Van Zanten Gallagher, S. Literature and the Renewal of the Public Sphere; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. WHO Global Disability Action Plan 2014–2021; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland. Available online: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/199544/1/9789241509619_eng.pdf (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- United Nations. Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD). Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities.html (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- United Nations. United Nations 2018 Flagship Report on Disability and Development: Realization of the Sustainable Development Goals by, for and with Persons with Disabilities. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/publication-disability-sdgs.html#:~:text=%E2%80%9CThe%20UN%20Flagship%20Report%20on,can%20create%20a%20more%20inclusive (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- Diep, L. Master Thesis: Anticipatory Governance, Anticipatory Advocacy, Knowledge Brokering, and the State of Disabled People’s Rights Advocacy in Canada: Perspectives of Two Canadian Cross-Disability Rights Organizations. Available online: https://prism.ucalgary.ca/bitstream/handle/11023/4051/ucalgary_2017_diep_lucy.pdf?sequence=3&isAllowed=y (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- Hurst, R. The international disability rights movement and the ICF. Disabil. Rehabil. 2003, 25, 572–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayerson, A. The History of the Americans with Disabilities Act. Available online: https://dredf.org/about-us/publications/the-history-of-the-ada/ (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- Li, H.; Bora, D.; Salvi, S.; Brady, E. Slacktivists or Activists? Identity Work in the Virtual Disability March. In Proceedings of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Montreal, QC, Canada, 21–26 April 2018; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Wolbring, G. Ability Expectation and Ableism Governance: An Essential Aspect of a Culture of Peace. Available online: https://eubios.info/yahoo_site_admin/assets/docs/Legaciesbook1October2019.273183519.pdf#page=124 (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- Fenney, D. Ableism and Disablism in the UK Environmental Movement. Environ. Values 2017, 26, 503–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank; World Health Organization. World Report on Disability. Available online: https://www.who.int/disabilities/world_report/2011/report.pdf (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- Martin, K.; Franklin, A. Disabled children and participation in the UK: Reality or rhetoric? In A Handbook of Children and Young People’s Participation; Percy-Smith, B., Thomas, N., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 119–126. [Google Scholar]

- Malone, K.; Hartung, C. Challenges of participatory practice with children. In A handbook of Children and Young People’s Participation; Percy-Smith, B., Thomas, N., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 46–60. [Google Scholar]

- Feinstein, C.; Giertsen, A.; O’Kane, C. Children’s participation in armed conflict and postconflict peacebuilding. In A Handbook of Children and Young People’s Participation: Perspectives from Theory and Practice; Routledge; Percy-Smith, B., Thomas, N., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 53–62. [Google Scholar]

- Wolbring, G.; Mackay, R.; Rybchinski, T.; Noga, J. Disabled People and the Post-2015 Development Goal Agenda through a Disability Studies Lens. Sustainability 2013, 5, 4152–4182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Participants of the UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UNDESA) and UNICEF Organized Online Consultation—8 March–5 April Disability Inclusive Development Agenda Towards 2015 & Beyond. Disability Inclusive Development Agenda towards 2015 & Beyond. Available online: http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/news/social/disability-inclusive-development.html (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- Participants of the Global Online Discussion on Science Technology and Innovation for SDGs. Global Online Discussion on Science, Technology and Innovation for SDGs. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/forum/?forum=20 (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- The Journal Leonardo. About. Available online: https://www.mitpressjournals.org/loi/leon (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- Jacobs, R. The Artists’ Footprint: Investigating the Distinct Contributions of Artists Engaging the Public with Climate Data. Leonardo 2016, 49, 461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, C.O. On the Edge of Science: The Role of the Artist’s Intuition in Science. Leonardo 1992, 25, 249–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasšek, M.T. The Role of Artists and Scientists in Times of War. Leonardo 2002, 35, 228–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rewakowicz, A. Anti-entropic role of art. Leonardo 2014, 47, 76–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czegledy, N. Art as a Catalyst. Leonardo 2014, 47, 492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoro, A. Return to SOURCE: Contemporary Composers Discuss the Sociopolitical Implications of Their Work. Leonardo Music J. 2015, 25, 100–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiebig, G. The Sonic Witness: On the Political Potential of Field Recordings in Acoustic Art. Leonardo Music J. 2015, 25, 14–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullot, N.J. The functions of environmental art. Leonardo 2014, 47, 511–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandler, L.; Baldwin, C.; Marks, M. Catalysts for change: Creative practice as an environmental engagement tool. Leonardo 2014, 47, 506–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siler, T. Neuroart: Picturing the neuroscience of intentional actions in art and science. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2015, 9, 410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maurides, P.; Behrmann, M. The brain as muse: Bridging art and neuroscience. Leonardo 2017, 50, 190–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, D.R. Toward a critical neuroart for a critical neuroscience. Leonardo 2020, 53, 123–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biofaction. BIO·FICTION Science Art Film Festival 2019 Program Topic FUTUREBODY and Neurotechnologies. Available online: https://bio-fiction.com/program-2/ (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- Rogers, H. Amateur knowledge: Public art and citizen science. Configurations 2011, 19, 101–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seyfried, G.; Pei, L.; Schmidt, M. European do-it-yourself (DIY) biology: Beyond the hope, hype and horror. Bioessays 2014, 36, 548–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmer, H.B.; Disalvo, C.; Sengers, P.; Lodato, T. Constructing and constraining participation in participatory arts and HCI. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 2015, 74, 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darcy, S.; Maxwell, H.; Grabowski, S.; Onyx, J. Artistic Impact: From Casual and Serious Leisure to Professional Career Development in Disability Arts. Leis. Sci. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Wit, M.M. Democratizing CRISPR? Stories, practices, and politics of science and governance on the agricultural gene editing frontier. Elem. Sci. Anth. 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vignone, K. Democratizing Nanotechnology: The Nanoscale Informal Science Education Network and the Meaning of Civic Education. Available online: https://ecommons.cornell.edu/bitstream/handle/1813/33884/kdv5.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- Roeser, S.; Taebi, B.; Doorn, N. Geoengineering the climate and ethical challenges: What we can learn from moral emotions and art. Crit. Rev. Int. Soc. Political Philos. 2019, 23, 641–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balmer, A.S.; Calvert, J.; Marris, C.; Molyneux-Hodgson, S.; Frow, E.; Kearnes, M.; Bulpin, K.; Schyfter, P.; Mackenzie, A.; Martin, P. Five rules of thumb for post-ELSI interdisciplinary collaborations. J. Responsible Innov. 2016, 3, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halfon, S.E.; Olson, C.; Kilkelly, A.; Lehr, J.L. Engaging Theatre, Activating Publics: Theory and Practice of a Performance on Darwin. Engag. Sci. Technol. Soc. 2020, 6, 255–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Last, A. Mutable matter: Using sensory methods in public engagement with nanotechnology. Leonardo 2012, 45, 132–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, C.; Ranaivoson, H.; Greinke, B.; Bryan-Kinns, N. WEAR: Wearable technologists engage with artists for responsible innovation: Processes and progress. Virtual Creat. 2018, 8, 91–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coeckelbergh, M. The art, poetics, and grammar of technological innovation as practice, process, and performance. AI Soc. 2018, 33, 501–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuijff, M.; Dijkstra, A.M. Practices of Responsible Research and Innovation: A Review. Sci. Eng. Ethics 2020, 26, 533–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinsborough, M. Art-Science Collaboration in an EPSRC/BBSRC-Funded Synthetic Biology UK Research Centre. NanoEthics 2020, 14, 93–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heras, M.; Ruiz-Mallén, I.; Gallois, S. Staging science with young people: Bringing science closer to students through stand-up comedy. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2020, 42, 1968–1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torre, M. Impossible pictures: When art helps science education. In Proceedings of the 16th Conference on Applied Mathematics, APLIMAT 2017—Proceedings, Bratislava, Slovakia, 31 January–2 February 2017; pp. 1513–1527. [Google Scholar]

- Coenen, C. Broadening discourse on responsible research and innovation (RRI). Nanoethics 2016, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Göbel, C.; Agnello, G.; Baïz, I.; Berditchevskaia, A.; Evers, L.; García, D.; Pritchard, H.; Luna, S.; Ramanauskaite, E.M.; Serrano, F.; et al. Report European Stakeholder Round Table on Citizen and DIY Science and Responsible Research and Innovation. Available online: https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/1563626/7/Report%20on%20DITOs%20Round%20Table%20on%20Citizen%20Science%20DIY%20Science%20and%20RRI.pdf (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- Pansera, M.; Owen, R.; Meacham, D.; Kuh, V. Embedding responsible innovation within synthetic biology research and innovation: Insights from a UK multi-disciplinary research centre. J. Responsible Innov. 2020, 7, 384–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymanski, E.; Bates, T.; Cachat, E.; Calvert, J.; Catts, O.; Nelson, L.J.; Rosser, S.J.; Smith, R.D.; Zurr, I. Crossing Kingdoms: How Can Art Open Up New Ways of Thinking About Science? Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swierstra, T.; Pérez, E.; Efstathiou, S. Getting our Hands Dirty with Technology. Available online: https://tidsskrift.dk/peripeti/article/view/117599 (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- Aryan, V.; Bertling, J.; Liedtke, C. Topology, typology, and dynamics of commons-based peer production: On platforms, actors, and innovation in the maker movement. Creat. Innov. Manag. 2020, 30, 63–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stark, L.; Crawford, K. The work of art in the age of artificial intelligence: What artists can teach us about the ethics of data practice. Surveill. Soc. 2019, 17, 442–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bureaud, A. What’s art got to do with it? Reflecting on bioart and ethics from the experience of the trust Me, I’m an artist project. Leonardo 2018, 51, 85–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumitriu, A. Trust Me, I’M an Artist: Building opportunities for art and science collaboration through an understanding of ethics. Leonardo 2018, 51, 83–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yassi, A.; Spiegel, J.B.; Lockhart, K.; Fels, L.; Boydell, K.; Marcuse, J. Ethics in Community-University-Artist Partnered Research: Tensions, Contradictions and Gaps Identified in an ‘Arts for Social Change’ Project. J. Acad. Ethics 2016, 14, 199–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gigliotti, C. Leonardo’s choice: The ethics of artists working with genetic technologies. AI Soc. 2006, 20, 22–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laszlo, E. The alliance of science and art for human survival. World Futures 1994, 40, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, C. The Social Responsibility of Artists. In Culture and Democracy: Social and Ethical Issues in Public Support for the Arts and Humanities; Buchwalter, A., Ed.; Westview Press: Boulder, CO, USA, 1992; pp. 239–247. [Google Scholar]

- Zuidervaart, L. Art in Public: Politics, Economics, and a Democratic Culture; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010; pp. 1–338. [Google Scholar]

- Powers, M.J. Artistic Status and Social Agency. In A Companion to Chinese Art; Powers, M.J., Tsiang, K.R., Eds.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 349–370. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott, D.; Silverman, M.; Bowman, W. Artistic Citizenship: Artistry, Social Responsibility, and Ethical Praxis; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zuidervaart, L. Creative border crossing in new public culture. In Literature and the Renewal of the Public Sphere; Walhout, M., Van Zanten Gallagher, S., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2000; pp. 206–224. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, D. Bioart and the Communication Paradigm of Responsibility. Available online: https://davidetxeberria.wordpress.com/work/2012-2/bioart-and-the-communication-paradigm-of-responsibility-2012/ (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- Magazzini, T. Identity as a Weapon of the Weak? Understanding the European Roma Institute for Arts and Culture—An Interview with Tímea Junghaus and Anna Mirga-Kruszelnicka. In The Roma and Their Struggle for Identity in Contemporary Europe; Baar, H.v., Kóczé, A., Eds.; Berghahn Books: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 281–305. [Google Scholar]

- Drioli, A. Artists and now also activists to contrast global warming. J. Sci. Commun. 2008, 7, C03. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lea, S. Arts activism and the democratisation of the photographic image. Crim. Justice Matters 2009, 78, 21–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hancox, S. Art, activism and the geopolitical imagination: Ai Weiwei’s ‘Sunflower Seeds’. J. Media Pract. 2012, 12, 279–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokes-Casey, J. Whiteness and Masculinity in Richard Lou’s ReCovering Memphis: ReContexting Bodies. J. Am. Stud. 2020, 54, 407–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michéle, A.; Johnson, C. Art and our surrounds: Emergent and residual languages. ARTMargins 2020, 9, 58–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommer, L.K.; Swim, J.K.; Keller, A.; Klöckner, C.A. “Pollution Pods”: The merging of art and psychology to engage the public in climate change. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2019, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, S. Disobedient objects: Towards a museum insurgency. J. Curator. Stud. 2018, 7, 2–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, J.C. Citizen Participation in Science Policy; University of Massachusetts Press: Amherst, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Bandelli, A.; Konijn, E. An experimental approach to strengthen the role of science centers in the governance of science. In The Routledge Companion to Museum Ethics; Marstine, J., Ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 164–173. [Google Scholar]

- Bandelli, A.; Konijn, E.A. Public participation and scientific citizenship in the science museum in London: Visitors’ perceptions of the museum as a broker. Visit. Stud. 2015, 18, 131–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Meij, M.G.; Broerse, J.; Kupper, F. RRI & science museums; prototyping an exhibit for reflection on emerging and potentially controversial research and innovation. J. Sci. Commun. 2017, 16, A02. [Google Scholar]

- Schrögel, P.; Kolleck, A. The Many Faces of Participation in Science. Sci. Technol. Stud. 2019, 32, 77–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kano, K.; Kudo, M.; Yoshizawa, G.; Mizumachi, E.; Suga, M.; Akiya, N.; Ebina, K.; Goto, T.; Itoh, M.; Joh, A. How science, technology and innovation can be placed in broader visions-Public opinions from inclusive public engagement activities. J. Sci. Commun. 2019, 18, A02. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynn, S.J.; Kaplan, N.; Newman, S.; Scarpino, R.; Newman, G. Designing a Platform for Ethical Citizen Science: A Case Study of CitSci.org. Citiz. Sci. Theory Pract. 2019, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, E. Equity in informal science education: Developing an access and equity framework for science museums and science centres. Stud. Sci. Educ. 2014, 50, 209–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostman, R.; Herring, B.; Jackson, A.; Bennett, I.; Wetmore, J. Making Meaning through Conversations about Science and Society. Exhibitionist 2013, 32, 42–47. [Google Scholar]

- King, A. Exhibition A: Scientist at work: Science museums are shifting their focus away from educating and elating their audiences to fostering dialogue with scientists. EMBO Rep. 2016, 17, 486–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandelli, A.; Konijn, E.A. Science centers and public participation: Methods, strategies, and barriers. Sci. Commun. 2013, 35, 419–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owens, S.R.; Lecrubier, A.; Breithaupt, H. A day at the museum: Science centres and museums play an increasingly important role in bringing science and technology to the public. EMBO Rep. 2002, 3, 506–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodari, P.; Merzagora, M. The role of science centres and museums in the dialogue between science and society. J. Sci. Commun. 2007, 6, C01. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Wolbring, G. Employment, disabled people and robots: What is the narrative in the academic literature and Canadian newspapers? Societies 2016, 6, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lillywhite, A.; Wolbring, G. Coverage of ethics within the artificial intelligence and machine learning academic literature: The case of disabled people. Assist. Technol. 2019, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lillywhite, A.; Wolbring, G. Coverage of Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning within Academic Literature, Canadian Newspapers, and Twitter Tweets: The Case of Disabled People. Societies 2020, 10, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, M.J.; Booth, A. A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Inf. Libr. J. 2009, 26, 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, K.; Drey, N.; Gould, D. What are scoping studies? A review of the nursing literature. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2009, 46, 1386–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levac, D.; Colquhoun, H.; O’Brien, K.K. Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implement. Sci. 2010, 5, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britannica. Disability Art. Available online: https://www.britannica.com/art/disability-art (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- Panagiotara, B.; Evans, B.; Pawlak, F. Disabled Artists in the Mainstream: A New Cultural Agenda for Europe. Available online: https://www.disabilityartsinternational.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Report_A-new-cultural-agenda-for-Europe-FINAL-050320.pdf (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- Perram, M. Reimagining the World through Disability Arts and Justice. Available online: https://congress2021.ca/congress-blog/reimagining-world-through-disability-arts-and-justice (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- Holloway, R. Artists as Defenders: Disability Art as Means to Mobilise Human Rights. Available online: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/58a1a2bb9f745664e6b41612/t/607d35f179634c124c5d383d/1618818546294/Working+Paper+10+%28accessible%29.pdf (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- Wikipedia. Disability Art. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Disability_art#:~:text=Disability%20art%20or%20disability%20arts,whose%20context%20relates%20to%20disability (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- Canada Council for the Arts. Disability Arts. Available online: https://canadacouncil.ca/glossary/disability-arts (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- Hsieh, H.-F.; Shannon, S.E. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual. Health Res. 2005, 15, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edling, S.; Mooney Simmie, G. Democracy and emancipation in teacher education: A summative content analysis of teacher educators’ democratic assignment expressed in policies for Teacher Education in Sweden and Ireland between 2000–2010. Citizsh. Soc. Econ. Educ. 2017, 17, 20–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Successful Qualitative Research: A Practical Guide for Beginners; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, V.; Braun, V. Thematic analysis. In Encyclopedia of Critical Psychology; Teo, T., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 1947–1952. [Google Scholar]

- Downe-Wamboldt, B. Content analysis: Method, applications, and issues. Health Care Women Int. 1992, 13, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baxter, P.; Jack, S. Qualitative case study methodology: Study design and implementation for novice researchers. Qual. Rep. 2008, 13, 544–559. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln, Y.S.; Guba, E.G. Naturalistic Inquiry; SAGE Publications: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Shenton, A.K. Strategies for ensuring trustworthiness in qualitative research projects. Educ. Inf. 2004, 22, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandahl, C. Disability art and culture: A model for imaginative ways to integrate the community. Alter 2018, 12, 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, C. Whose problem? Disability narratives and available identities. Community Dev. J. 2007, 42, 501–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandler, E.; Aubrecht, K.; Ignagni, E.; Rice, C. Cripistemologies of Disability Arts and Culture: Reflections on the Cripping the Arts Symposium. Stud. Soc. Justice 2021, 15, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decottignies, M. Disability Arts and Equity in Canada. CTR 2016, 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, C.; Orsini, M. Beyond Measure? Disability Art, Affect and Reimagining Visitor Experience. Stud. Soc. Justice 2021, 15, 288–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solvang, P.K. From identity politics to dismodernism? Changes in the social meaning of disability art. Alter 2012, 6, 178–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipkin, J.; Haddad, R. “Be Fierce, Believe in Yourself, and Find Your People”: A Roundtable Discussion about Disability and Performance. J. Lit. Cult. Disabil. Stud. 2018, 12, 221–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Symeonidou, S. Disability, the arts and the curriculum: Is there common ground? Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 2019, 34, 50–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, C. Tragic but brave or just crips with chips? Songs and their lyrics in the Disability Arts Movement in Britain. Pop. Music 2009, 28, 381–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allan, J. Encounters with exclusion through disability arts. J. Res. Spec. Ed. Needs 2005, 5, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boeltzig, H.; Sullivan Sulewski, J.; Hasnain, R. Career development among young disabled artists. Disabil. Soc. 2009, 24, 753–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bang, G.H.; Kim, K.M. Korean disabled artists’ experiences of creativity and the environmental barriers they face. Disabil. Soc. 2015, 30, 543–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allan, J. Inclusive education and the arts. Camb. J. Educ. 2014, 44, 511–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhauer, J. Just Looking and Staring Back: Challenging Ableism Through Disability Performance Art. Stud. Art Educ. 2007, 49, 7–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roman, L.G. Disability arts and culture as public pedagogy. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2009, 13, 667–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ware, L. Worlds remade: Inclusion through engagement with disability art. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2008, 12, 563–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keifer-Boyd, K.; Bastos, F.; Richardson, J.; Wexler, A. Disability Justice: Rethinking “Inclusion” in Arts Education Research. Stud. Art Educ. 2018, 59, 267–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, J.T.; Milbern, S.; Shanks, M.; Vaid-Menon, A.; Wong, A.; Berne, P. “Beauty Always Recognizes Itself”: A Roundtable on Sins Invalid. Women’s Stud. Q. 2018, 46, 241–251. [Google Scholar]

- Ware, L. When Art Informs: Inviting Ways to See the Unexpected. Learn. Disabil. Q. 2011, 34, 194–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadley, B. Allyship in disability arts: Roles, relationships, and practices. Res. Drama Educ. J. Appl. Theatre Perform. 2020, 25, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadley, B. (Dia)logics of Difference Disability, performance and spectatorship in Liz Crow’s Resistance on the Plinth. Perform. Res. 2011, 16, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solvang, P.K. Between art therapy and disability aesthetics: A sociological approach for understanding the intersection between art practice and disability discourse. Disabil. Soc. 2018, 33, 238–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darke, P.A. Now I know why disability art is drowning in the river Lethe (with thanks to Pierre Bourdieu). In Disability, Culture and Identity; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 131–142. [Google Scholar]

- Newsinger, J.; Green, W. Arts policy and practice for disabled children and young people: Towards a ‘practice spectrum’ approach. Disabil. Soc. 2016, 31, 357–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Casling, D. Art for whose sake? Disabil. Soc. 1994, 9, 383–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadley, B. Disability, Public Space Performance and Spectatorship: Unconscious Performers; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2014; pp. 1–210. [Google Scholar]

- Lobel, B. Spokeswomen and posterpeople: Disability, advocacy and live art. Contemp. Theatre Rev. 2012, 22, 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidler, C.O. Fighting Disability Stereotypes with Comics: “I Cannot See You, but I Know You Are Staring at Me”. Art Educ. 2011, 64, 20–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millett-Gallant, A.; Howie, E. Disability and Art History; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; pp. 1–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, Y. Disability and Postdramatic Theater: Return of Storytelling. J. Lit. Cult. Disabil. Stud. 2018, 12, 203–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brylla, C. Bypassing the Supercrip Trope in Documentary Representations of Blind Visual Artists. Disabil. Stud. Q. 2018, 38, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, A.C.B. Impossible dances: Staging disability in Brazil. Choreographic Pract. 2017, 6, 9–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAskill, A. “Come and see Our Art of Being Real”: Disabling Inspirational Porn and Rearticulating Affective Productivities. Theatre Res. Can. 2016, 37, 201–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, M. Cripping it up. J. Vis. Art Pract. 2013, 12, 245–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandler, E.; Changfoot, N.; Rice, C.; LaMarre, A.; Mykitiuk, R. Cultivating Disability Arts in Ontario. Rev. Educ. Pedagog. Cult. Stud. 2018, 40, 249–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millett, A. Sculpting Body Ideals: Alison Lapper Pregnant and the Public Display of Disability. Disabil. Stud. Q. 2008, 28, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiff, D. Information Behaviors of Deaf Artists. Art Doc. Bull. Art Libr. Soc. North Am. 2010, 29, 44–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Santesmases Fernández, A.; Arenas Conejo, M. Playing crip: The politics of disabled artists’ performances in Spain. Res. Drama Educ. 2017, 22, 345–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadman, B. Diffractive Co-conspiracy in Queer, Crip Live Art Production. Perform. Res. 2020, 25, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bieber, R. The Truth about Theatre from the Inside Out. CTR 2005, 122, 55–58. [Google Scholar]

- Rouse, J. Reflexive Sketches during the Cripping the Arts Symposium. Stud. Soc. Justice 2021, 15, 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, D. Shooting Blind. Hist. Photogr. 2003, 27, 200–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doolittle, L.; Chasse, C.; Makoloski, C.; Boyd, P.; Yassi, A. May I have this dance? Teaching, Performing, and Transforming in a University-Community Mixed-Ability Dance Theatre Project. Theatre Res. Can. 2016, 37, 239–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, H. Casting a Doubt: The Legal Issues of Nontraditional Casting. J. Arts Manag. Law 1989, 19, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boys, J. Invisibility work? How starting from dis/ability challenges normative social, spatial and material practices. In Architecture and Feminisms: Ecologies, Economies, Technologies; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 270–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weise, J. Biohack manifesto. In The Disability Studies Reader, 5th ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 519–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creed, C. Assistive tools for disability arts: Collaborative experiences in working with disabled artists and stakeholders. J. Assist. Technol. 2016, 10, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creed, C. Eye gaze interaction for supporting creative work with disabled artists. In Proceedings of the 30th International BCS Human Computer Interaction Conference, HCI 2016, Poole, UK, 11–15 July 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Creed, C. Assistive technology for disabled visual artists: Exploring the impact of digital technologies on artistic practice. Disabil. Soc. 2018, 33, 1103–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, G.C. Autonomy of Artistic Expression for Adult Learners with Disabilities. Int. J. Art Des. Educ. 2008, 27, 116–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinberg, N. Disabled Artists Explore Social Issues. Available online: https://georgetownvoice.com/2012/09/20/disabled-artists-explore-social-issues/ (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- National Disability Arts Collection & Archives. Artists and Activists. Available online: https://the-ndaca.org/the-people/ (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- Disability Arts Online. Disability Arts Online. Available online: https://disabilityarts.online/ (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- Roaring Girl Productions. Roaring Girl Productions. Available online: http://www.roaring-girl.com/ (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- Sins Invalid. Sins Invalid. Available online: https://www.sinsinvalid.org/ (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- Ware, S.M. Magic from the Madness: On Black Disabled Activists and Artists Making Change in 2016. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/arts/magic-from-the-madness-on-black-disabled-activists-and-artists-making-change-in-2016-1.3911410 (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- Gore, S. Meet Sharona Franklin, the Artist Using Memes to Dismantle Ableism. Available online: https://www.byrdie.com/sharona-franklin-interview-5079044 (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- Taylor, S. Sunaura Taylor. Available online: http://www.sunaurataylor.com/contact (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- Pring, J. Coronavirus: Action Celebrates Disability Arts while Highlighting Pandemic Concerns. Available online: https://www.disabilitynewsservice.com/coronavirus-action-celebrates-disability-arts-while-highlighting-pandemic-concerns/ (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- Funds for NGO’s. Shape Arts: Seeking Proposals from Disabled Artists. Available online: https://www2.fundsforngos.org/arts-and-culture/shape-arts-seeking-proposals-from-disabled-artists/ (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- Arts Professional. Investing in Disabled Artists. Available online: https://www.artsprofessional.co.uk/magazine/article/investing-disabled-artists (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- Kuppers, P. Studying Disability Arts and Culture: An Introduction; Macmillan International Higher Education: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kuppers, P. Disability Arts and Culture: Methods and Approaches; Intellect Books: Bristol, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hadley, B.; McDonald, D. The Routledge Handbook of Disability Arts, Culture, and Media; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Disability Arts Online. UKDHM presents History of Disability and Art Conference, London. Available online: https://disabilityarts.online/events/ukdhm-presents-history-disability-art-conference-london/ (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- The 3rd International Disability Studies, Arts and Education Conference. The 3rd International Disability Studies, Arts and Education Conference. Available online: https://www.dsae2021.com/about (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- Turnbull, J. DIS_connect: Disability and Digital (im)mobilization—Panel Debate. Available online: https://disabilityarts.online/magazine/opinion/dis_connect-disability-and-digital-immobilisation-panel-debate/ (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- Weise, J. Common Cyborg. Available online: https://granta.com/common-cyborg/ (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- Young, B. I have One of the Most Advanced Prosthetic Arms in the World—And I hate it. Available online: https://www.inputmag.com/culture/cyborg-chic-bionic-prosthetic-arm-sucks (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- Chang, V.; Felt, L.D. Recoding CripTech. Available online: https://www.recodingcriptech.com/ (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- Publisher, I. Technoetic Arts: A Journal of Speculative Research (Journal). Available online: https://www.intellectbooks.com/technoetic-arts-a-journal-of-speculative-research (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- Journal of Science and Technology of the Arts. Journal of Science and Technology of the Arts. Available online: http://artes.ucp.pt/citarj/about (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- Hagen, K. Science policy and concomitant research in synthetic biology—Some critical thoughts. Nanoethics 2016, 10, 201–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jho, H. Implications of science education as interdisciplinary education through the cases of scientists and artists in the modern era: Focus on the relationship between science and the arts. J. Korean Assoc. Sci. Educ. 2014, 34, 755–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emdin, C. Affiliation and alienation: Hip-hop, rap, and urban science education. J. Curric. Stud. 2010, 42, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emdin, C.; Adjapong, E.; Levy, I. Hip-hop based interventions as pedagogy/therapy in STEM: A model from urban science education. J. Multicult. Educ. 2016, 10, 307–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatalovic, M. Science comics as tools for science education and communication: A brief, exploratory study. J. Sci. Commun. 2009, 8, A02. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcadias, L.; Corbet, R.H.; McKenna, D.; Potenziani, I. Astro-animation-A case study of art and science education. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2104.06215. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Mallén, I.; Heras, M.; Berrens, K. Responsible research and innovation in science education: Insights from evaluating the impact of using digital media and arts-based methods on RRI values. Res. Sci. Technol. Educ. 2020, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandelli, A.; Konijn, E.A.; Willems, J.W. The need for public participation in the governance of science centers. Mus. Manag. Curatorship 2009, 24, 89–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greco, P. Science museums in a knowledge-based society. J. Sci. Commun. 2007, 6, C02. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyer, J. THIS “ME” OF MINE. Available online: https://thismeofmine.wordpress.com/2012/05/01/no-no-no-kate-murdoch-exhibits-with-shape-open-2012/ (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- Johnston, K. Building a Canadian disability arts network: An intercultural approach. Theatre Res. Can. 2009, 30, 152–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharapan, H. From STEM to STEAM: How Early Childhood Educators Can Apply Fred Rogers’ Approach. Young Child. 2012, 67, 36–40. [Google Scholar]

- Arrieta, D.; Kern, J. Art outreach toward STEAM and academic libraries. New Libr. World 2015, 116, 677–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanbari, S. Learning across Disciplines: A Collective Case Study of Two University Programs That Integrate the Arts with STEM. Int. J. Educ. Arts 2015, 16, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Costantino, T. STEAM by another name: Transdisciplinary practice in art and design education. Arts Educ. Policy Rev. 2018, 119, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejias, S.; Thompson, N.; Sedas, R.M.; Rosin, M.; Soep, E.; Peppler, K.; Roche, J.; Wong, J.; Hurley, M.; Bell, P. The trouble with STEAM and why we use it anyway. SciEd 2021, 105, 209–231. [Google Scholar]

- Farman, N.; Barr, M.; Philp, A.; Lawry, M.; Belcher, W.; Dastoor, P. Model & metaphor: A case study of a new methodology for art/science residencies. Leonardo 2015, 48, 419–423. [Google Scholar]

- Wolbring, G.; Lillywhite, A. Equity/Equality, Diversity, and Inclusion (EDI) in Universities: The Case of Disabled People. Societies 2021, 11, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Strategy | Sources Used | Search Terms Used |

|---|---|---|

| Strategy 1a | SCOPUS | (“disabled art*” OR “art* with a disability” OR “deaf art*” OR “blind art*” OR “art* with disabilities” OR “art* with a learning disability” OR “art* with a physical disability” OR “art* with a hearing impairment” OR “art* with a visual impairment” OR “art* with a mental disability” OR “art* with a mental health” OR “learning disability art*” OR “learning disabled art*” OR “physical disability art*” OR “physically disabled art*” OR “hearing impaired art*” OR “visually impaired art*” OR “mental health art*” OR “autism art*” OR “autistic art*” OR “art* with autism” OR “ADHD art*” OR “art* with ADHD” OR “art* with mental disabilities” OR “art* with a mental disability” OR “mental disability art*” OR “mentally disabled art*” OR “neurodiverse art*” OR neurodiversity art*”) |

| Strategy 1b | EBSCO-HOST | (“disabled art*” OR “art* with a disability” OR “deaf art*” OR “blind art*” OR “art* with disabilities” OR “art* with a learning disability” OR “art* with a physical disability” OR “art* with a hearing impairment” OR “art* with a visual impairment” OR “art* with a mental disability” OR “art* with a mental health” OR “learning disability art*” OR “physical disability art*” OR “physically disabled art*” OR “hearing impaired art*” OR “visually impaired art*” OR “mental health art*” OR “autism art*” OR “autistic art*” OR “art* with autism” OR “ADHD art*” OR “art* with ADHD” OR “art* with a mental health” OR “art* with mental disabilities” OR “mentally disabled art*” OR “neurodiverse art*” OR “neurodiversity art*) |

| Strategy 1c | EBSCO-HOST | (“disabled artist*” OR “artist* with a disability” OR “deaf artist*” OR “blind artist*” OR “artist* with disabilities” OR “artist* with a learning disability” OR “artist* with a physical disability” OR “artist* with a hearing impairment” OR “artist* with a visual impairment” OR “artist* with a mental disability” OR “artist* with a mental health” OR “learning disability artist*”OR “learning disabled artist*” OR “physical disability artist*” OR “physical disabled artist*” OR “physically disabled artist*” OR “hearing impaired artist*” OR “visually impaired artist*” OR “autism artist*” OR “autistic artist*” OR “artist* with autism” OR “ADHD artist*” OR “artist* with ADHD” OR “artist* with mental disabilities” OR “mental health artist*” OR “mental disability artist*” OR “mentally disabled artist*” OR “neurodiverse artist*”) |

| Strategy 2a | SCOPUS | “disability art*” |

| Strategy 2b | EBSCO-HOST | “disability art” OR “disability arts” |

| Themes | Subthemes Mentioned More than Once | Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| Social role of disability art(s) | Informed by disabled people | 7 |

| For disabled people | 4 | |

| Make life of disabled people better | 8 | |

| Enable disabled people | 3 | |

| Disability arts is intersectional | 2 | |

| Disability arts is useful in school education | 8 | |

| Disability arts is political | 11 | |

| Disability arts movement | 6 | |

| Barriers to social role of disability arts | 4 | |

| Social role of disabled artists | Questioning and rectifying stereotype of disabled people | 20 |

| Disabled artists as political activists | 3 | |

| Fighting for rights and justice | 3 | |

| Disabled artists engage with intersectionality | 2 | |

| Barrier for social role of disabled artists | 5 | |

| Disabled artists and technology | Role of user and developer of technology for use in arts | 5 |

| Disabled artists and museums | All six have different sub-themes | 6 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wolbring, G.; Jamal Al-Deen, F. Social Role Narrative of Disabled Artists and Both Their Work in General and in Relation to Science and Technology. Societies 2021, 11, 102. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc11030102

Wolbring G, Jamal Al-Deen F. Social Role Narrative of Disabled Artists and Both Their Work in General and in Relation to Science and Technology. Societies. 2021; 11(3):102. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc11030102

Chicago/Turabian StyleWolbring, Gregor, and Fatima Jamal Al-Deen. 2021. "Social Role Narrative of Disabled Artists and Both Their Work in General and in Relation to Science and Technology" Societies 11, no. 3: 102. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc11030102

APA StyleWolbring, G., & Jamal Al-Deen, F. (2021). Social Role Narrative of Disabled Artists and Both Their Work in General and in Relation to Science and Technology. Societies, 11(3), 102. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc11030102