Abstract

The purpose of our study is to give an account of the process of institutional isomorphism, which, in France, leads non-profit organisations (NPO) to follow the management and professional model used by organisations in the same field because they are larger, better equipped, and have higher-performance tools and better skilled executive managers. In order to investigate this subject, we have built a rigorous methodology. We carried out an investigation by interviewing volunteer leaders running sports NPOs in the Nord and Pas-de-Calais departments (now part of the Hauts-de-France region). In total, we interviewed nearly 80 volunteer members of sports associations employing at least one employee and engaged in a process of professionalization. In the introduction, we highlight the managerial surge that leads associations to move closer to the managerial forms of organizations. To illustrate this phenomenon, we used the concepts of neo-institutional theory and tried to show that institutional isomorphism is collectively accepted by institutional volunteer leaders. In this process of professionalisation that affects sports organisations, our results demonstrate that this isomorphism operates on several levels. At a structural level, our study shows that the organisation imports the management and operating tools from the entrepreneurial model and develops strategies for diversifying its services and innovating its products. At a skills-based level, it appears the skills acquired by volunteers during their professional career are increasingly put to use in work with non-profits. Our study concludes that the isomorphism of sports NPOs is characterised by the need for independent funding, the diversification of activities, the search for innovation and the increased need for skills derived from professional experience. These results have led us to discuss the impact of the mimetic form of this isomorphic process on the non-profit project. The implications of this isomorphism are significant: while this process is very often the result of external pressure on the organisational field, it is also, in certain circumstances, the result of a collective strategy defined by the volunteer leaders running NPOs. Organisations must create the conditions for financial empowerment by increasing their financial resources. This isomorphism in NPOs with the business world is also made possible by hiring volunteers who are better trained and better adapted to new requirements. Finally, we highlight the limitations of our study and the possibilities for future development.

1. Managerial Surge and Isomorphic Trend of Sports NPOs

The complexity of the context being studied first of all requires a framing of the subject. Researchers across Europe and around the world are observing a managerial evolution of NPOs 1 [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15]. France is no more immune to this “surge of management” than anywhere else [16] (p. 114). The Derosier report also states that “the missions entrusted to associations are becoming increasingly technical” [17] (p. 35). Concerns about legal liability [5], bureaucratisation and red tape [18] are accentuating the formalisation of non-profit structures, making greater professional demands on volunteers. There are many authors who have tried to conceptualise the term “professionalisation” and there are multiple definitions, according to how it is approached by professions [19,20,21,22], professional groups [23,24,25], or by competencies [26,27]. By referring to the sociology of professions from the Anglo-Saxon functionalist approach, whihch perceives professionalisation as a process of transforming occupations into professions [28], studies on sports in particular are interested in emerging professions, such as leaders [29] and managers [30], as well as well-known professions, such as sports coaches [31]. From the perspective of professional groups, many authors have attempted to show how sports NPOs are moving towards restructuring as “non-profit companies” [13,32]. Others have tried to apply Mintzberg’s configurations to sports organisations [33,34,35,36,37,38,39]. As for researchers who establish a link between professionalisation and skills, they have noted a strengthening of skills and training content in sports and, in particular, among volunteer leaders [40,41,42]. Observing the “disenchantment of the world” of sport [43], the majority of studies conclude that the preponderance of professional and bureaucratic forms in sports NPOs is to the detriment of the mission-focused and social forms.

In reality, while it appears to have been gaining more traction in recent decades, this professional evolution is only an example of a deeper trend. Indeed, as many authors [44,45,46,47] highlight, we hypothesise that professionalisation reflects a more global phenomenon that affects all cultural, sports and social NPOs, and, more generally, the entire social and solidarity economy. This is institutional isomorphism as it is conceptualised by neo-institutional theory. From the literature that mentions theories of isomorphism in sport, we cite works by Hinings, Slack and Thibault [33], Meyer and Rowan [48], O’Brien and Slack [49], Hoye et al. [50], Edwards et al. [29], Stenling and Fahlén [51], Vos et al. [52], Dowling, Edwards and Washington [30], Nagel et al. [53], Nichols et al. (2015) and Stenling and Sam [54]. Nevertheless, as we will see further on, not all of these authors agree on the type of isomorphism that prevails in sport. Our aim is to better define the forms of isomorphisms in sport. What are sports NPOs in France? Are they affected by the process of isomorphism described by neo-institutional theorists? If so, which mechanisms of isomorphism seem to best characterise their professional development?

The neo-institutional theory originated in the United States in the 1970s. Its development is linked to its authors’ [48,55,56] desire to mark their distance from actor theories and, more generally, from individualism theories. Although this approach does not deny the small arrangements between actors, it fundamentally calls into question the capacity of the latter to manage themselves. It asserts that there can be no rational optimisation of individual behaviours. What matters most is the collective phenomenon influenced by institutional factors. Proponents of neo-institutional analysis do not consider collective action “as an aggregation of individual decisions, but rather as an important determinant of those decisions” [57] (p. 86). Therefore, the individual does not make decisions on their own. Although they know how to accommodate and play with rules and norms (see in particular the works by Suddaby, Greenwood and Hinings [58] in 2002), they nevertheless remain subject to group, institutional and environmental influences that condition their actions. If they act out of self-interest by referring to various forms of legitimisation [43], they are nonetheless influenced by the social and cultural norms that partly guide their choices. For theorists of neo-institutional theory, institutional isomorphism is therefore a collective action constructed in response to external constraints on the group and its organisation [44,59,60,61,62]. Hawley [63] defines it as a process of tension that drives one group or organisation to become more like another, more influential, group or organisation. In a seminal article published in 1983 [55], DiMaggio and Powell identified three mechanisms of institutional isomorphism. Coercive isomorphism is the consequence of formal and informal legal [56] imperatives, as well as accounting and bureaucratic pressures that push some organisations to become closer to other larger and more influential organisations in their structure and operations. With mimetic isomorphism, uncertainty about the future, or even the survival of non-profit organisations [64,65], encourages the latter to imitate other so-called dominant organisations that have adapted more effectively to the current climate: “When goals are ambiguous, or when the environment creates symbolic uncertainly, organizations may model themselves on other organizations”, [55] (p. 151). Lastly, normative isomorphism characterises a dominant professional group that tends to homogenise and standardise the norms, access and operational conditions of its professions. Environmental (economic and political) factors influence social factors and drive change.

Our intention, in fine, is to analyse the forms of isomorphism at play in sports. We want to see how this process impacts sports associations, and how it modifies their social project and transforms their members. We will thus see that our results highlight two levels of interpretation. At a structural level, our study shows that the organisation imports the management and operating tools from the entrepreneurial model, and develops strategies for diversifying its services and innovating its products. At a skills-based level, it appears that the skills acquired by volunteers during their professional career are increasingly put to use in work with non-profits. Our study concludes that the isomorphism of sports NPOs is characterised by the need for independent funding, the diversification of activities, the search for innovation, and the increased need for skills derived from professional experience. Our results will show that the implications of this isomorphism are significant: organisations must create the conditions for their financial empowerment by increasing their financial resources. This isomorphism of sports associations with the business world is also made possible by hiring volunteers who are better trained and better adapted to the new requirements. The consequences of this isomorphism are not negligible. Indeed, it can be assumed that they can durably modify the collective project of the association. The latter may gradually lose its non-profit character and erase the specificities that, until then, differentiated it from enterprises. Our study makes a contribution to a better understanding of this phenomenon of isomorphism, the effects of which will have to be evaluated in the short and long term.

2. Methodology

In order to answer these questions, we chose to conduct a qualitative analysis based on a population of volunteers. We selected a region and then several associations, by successive sorting, in order to define a representative sample able to account for the isomorphism process. We then constructed our interview guide.

The region and the population were selected in line with several criteria. We carried out an investigation by interviewing volunteers running sports NPOs in the Nord and Pas-de-Calais departments (now part of the Hauts-de-France region, since 2014). We chose to interview only volunteer leaders, because they are the easiest to contact, all have a uniform position defined by the 1901 law on associations, and all have strategic management positions. The choice of this region was also not insignificant because, although it is the least athletic in France, with a 41% rate of those who are not active compared to a national average of 35% (INJEP, 2018), for the last 15 years, it has seen a considerable increase in participation in sports (30% above the national average in 2018) and the professionalisation of structures and jobs in sport, with the latter progressing to more than 20% today (Horizon Eco 2015 no. 206).

We built our sample by successive sorting. This piece of work was carried out in collaboration with students on the Masters in Sports Management degree programme at the University of Lille. A total of 16 students were divided into two groups. The students formulated interview guidelines in class based on their own broad definition of professionalisation (based on professions, organisations and skills), which were put forward by students and then discussed as a group. The guidelines were then revised by the research team and tested on about ten well-known volunteer leaders living near the university. The sample population was chosen in three stages, according to a random method based on a less specific source population in the Nord and Pas-de-Calais departments. First of all, each student group listed the existing sports NPOs in their department. Those that employed at least one employee were then selected. The choice to select only NPOs that have employees can be explained by the fact that we wanted to interview only organisations that have already begun a process of professionalisation, with the introduction of a salaried employee being a preliminary step in most cases. The responses during the test from certain volunteer members of NPOs without employees have confirmed their very low level of awareness regarding the professionalisation process, and thus their low level of interest in the subject. The third separating process was then carried out based on the sports proposed (we wanted a diverse range of sports), the allocated budget (a minimum budget of EUR 50,000 appears necessary in order for us to contact only NPOs that are likely to be affected by professionalisation) and the number of members (we wanted our population to be made up of differently sized non-profit organisations). In the end, we selected 14 sports NPOs that offer a total of about 20 different sports (some NPOs are multi-sport) and a wide range of members (3 NPOs have fewer than 200 members, 4 have between 201 and 280 members, 3 have between 281 and 450 members and 4 have more than 451 members). Details can be found in Appendix A.

For the interview guide, we chose to carry out semi-structured interviews comprising a mix of open questions (especially on perceptions of professionalisation) and other, more structured questions on the links between professionalisation, volunteering, employment, skills, money, and the non-profit project. The interview contained 10 main questions (and several supplementary questions) focusing on the respondent’s civil status (sex, age, profession, position and status in the NPO), the key features of the NPO (number of members, sporting level of the club, number of employees and volunteers), how professionalisation is regarded, the relationship between volunteers and employees, the non-profit project’s accounts and, lastly, the skills acquired and how they were acquired. The face-to-face interviews lasted on average for about 30 min, and were held over the course of a month, with responses recorded anonymously.

A total of 77 volunteers were interviewed, two-thirds of whom were male and one-third female. They are from NPOs located in ten different municipalities that cover the two departments of the former Nord-Pas-De-Calais region (now the Hauts-de-France region). Further details are given in annexe 1. The responses were analysed by the research team, with the help of students, using RStudio software to establish any correlations and causal links.

3. Results

3.1. Professionalisation in Sport: Collectively Assumed Institutional Choice

Following the example of neo-institutional theory, our study of sports NPOs in the Nord and Pas-de-Calais departments shows that professionalisation is collectively accepted by institutional volunteer leaders. Indeed, 74% of our interviewees recognise the need to change the economic model of their non-profit organisation. Comments by the volunteer leaders we interviewed confirm these points:

“Non-profit organisations now have to function like businesses and have to know how to reinvent themselves if they want to develop and survive economically.” (E17)—“I think evolving is a natural thing, our model seems a bit outdated” (E71). Others talked about management that had “become obsolete” (E72), “a very outdated model” (E69) or the pressing need to “evolve in order to survive” (E76).

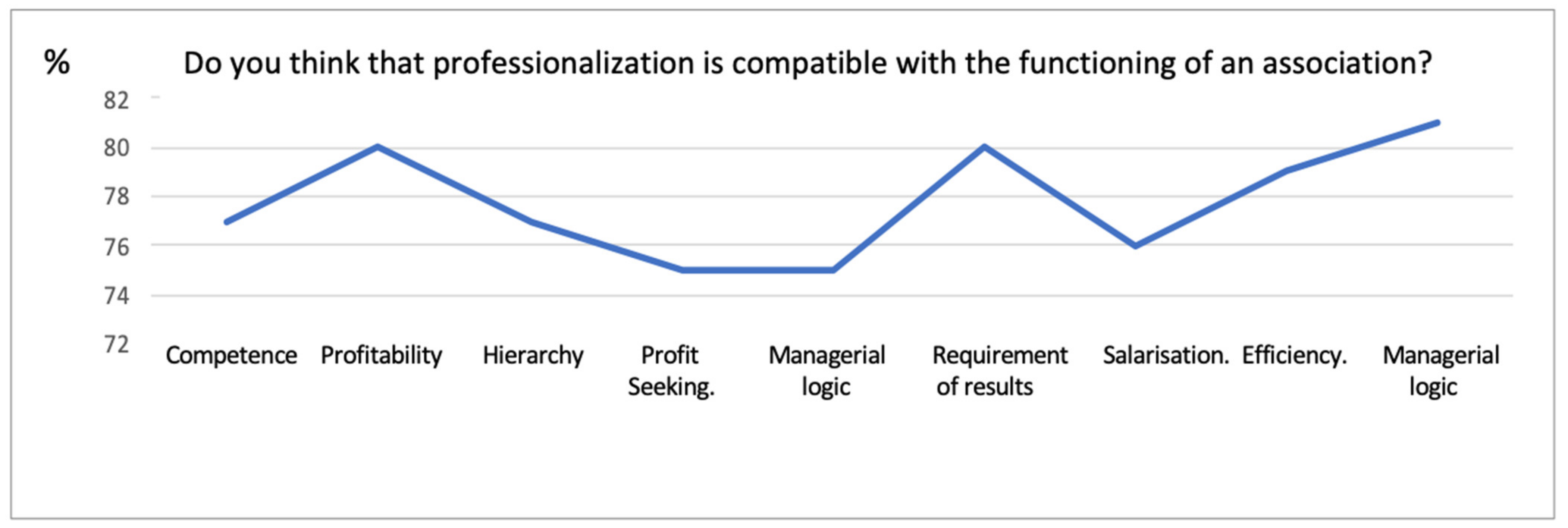

In answer to the question concerning the compatibility of associative functioning with the various markers of professionalisation (managerial logic, profitability, requirement of results, search for profit, etc.), more than 75% answered positively (80% of our interviewees fully accept the notions of profitability, obligation of results or managerial logic). (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The level of compatibility of non-profits functioning with professionalisation.

Of course, there are discourses and positions opposing professionalisation: “We noted a loss of values” (E75). “For me, there is no doubt that there is a fall in motivation and a lack of volunteers” (E54). “The search for profit cannot be reconciled with the managerial development of non-profit organisations” (E2). “I fear that this will call into question the non-profit project” (E81). “Professionalisation harms the essential non-profit aspect” (E36).

However, these positions are kept confidential and do not seem able to restrict a general movement that is characteristic of large sports non-profit organisations. Even if some volunteers regret it, and even if they sometimes show a certain disenchantment, the volunteer leaders we interviewed accepted that their non-profit organisation is closer to the form of entrepreneurial management. The evolution of the non-profit model is therefore not the work of a few isolated individuals. It is in fact the result of a collective will that unites volunteer leaders around the same common cause of having to adapt their organisation to an environment that has become uncertain and competitive. This evolution takes the form of a rationalisation of the different dimensions of the organisation that appear to be based on the entrepreneurial model [66,67,68]. We can therefore ask ourselves about the characteristics of this rationalisation.

3.2. Financial Independence, Diversification and Innovation in NPOs

For our volunteer leaders, it appears that the evolution of the desired economic model responds above all to the need to compensate for the decrease in public subsidies by seeking other methods of financing and not letting the company become too established in the sector of public and social action. In the context of our population, the interview extracts below illustrate volunteer awareness of the uncertainty of their environment: “There is a need to adjust to subsidy issues” (E33); “Societal development necessarily means that non-profit organisations have to find more effective ways to survive” (E25); “Non-profit organisations struggle to operate, so they need to change” (E70); “Funding strategies have to change now” (E72); “Cash needs to be conserved year on year for alternative investment” (E4); “Incorporating the idea of non-profit cooperatives in certain territories is now essential” (E69).

The professionalisation of sports NPOs results in the need to diversify the services and the need to innovate. In total, 81% of our respondents confirmed significant diversification in the private share of their revenues (Table 1). This includes the organisation of refreshment stands, sporting events linked to club life, lottery games, holiday training courses, sales of related products via an online shop or the sale of services to companies (evening entertainment, sports demonstrations, sports shows, etc.). These organisations are implementing a policy of diversifying activities, audiences and membership options. They are increasing the number of activities aimed specifically at children (baby football, baby handball, baby gym), seniors (handball leisure activities), people with disabilities (adapted handball, adapted tennis, wheelchair rugby) or those in employment (pass licences, sports tickets). They are offering activities in reduced numbers on smaller pitches (four-a-side handball, five-a-side football, half-court). This also translates into a diversification of membership options (à la carte options, taster options, holiday options). Innovation appears to be another area of development within the non-profit organisations that we interviewed. According to INSEE (Volunteer Opinion Barometer—INSEE Survey 2014), 89% of volunteers say they communicate by e-mail with members of the association; 35% use social media (Facebook, Twitter, etc.) to communicate about projects and announcements to do with their association. It should be noted that the use of digital tools is the highest in sports NPOs (93% for e-mail communication and 41% for using social media, respectively). In our sample, the respective percentages are 98% and 45%. These figures, which are above the national average, confirm the professionalising nature of the non-profit organisations in our panel. The vast majority of our interviewees use social media, e-mails and newsletters for their internal communication. They use websites, blogs, Padlets (a sort of “virtual wall” on which you can display all sorts of documents to circulate and share: text, images, audio recording, videos, webpages) and forums for their external communication. Our interviewees also reported using room reservation software via a platform (e.g., Fitogram, Deciplus, Resamania). They mastered IT tools for accounting management (Assoconnect) and used interactive or online tables to facilitate the distribution of tasks and schedules among volunteers. Some volunteers were even planning to equip themselves with the latest technology so they could, for example, communicate game results in real time.

Table 1.

Tools and materials for the managerial isomorphism of NPOs.

The table shows that, in terms of financial independence, 81% of the interviewees said that they have increased the private share of the revenues of their association. There was significant diversification of activities, the public and membership options. In the field of digitalization, 98% of the volunteers said they communicate by e-mail with the other members of the association, and 45% communicate their association’s projects and announcements via social media. They also use booking software and accounting software.

3.3. Skills Transfer from Businesses to NPOs

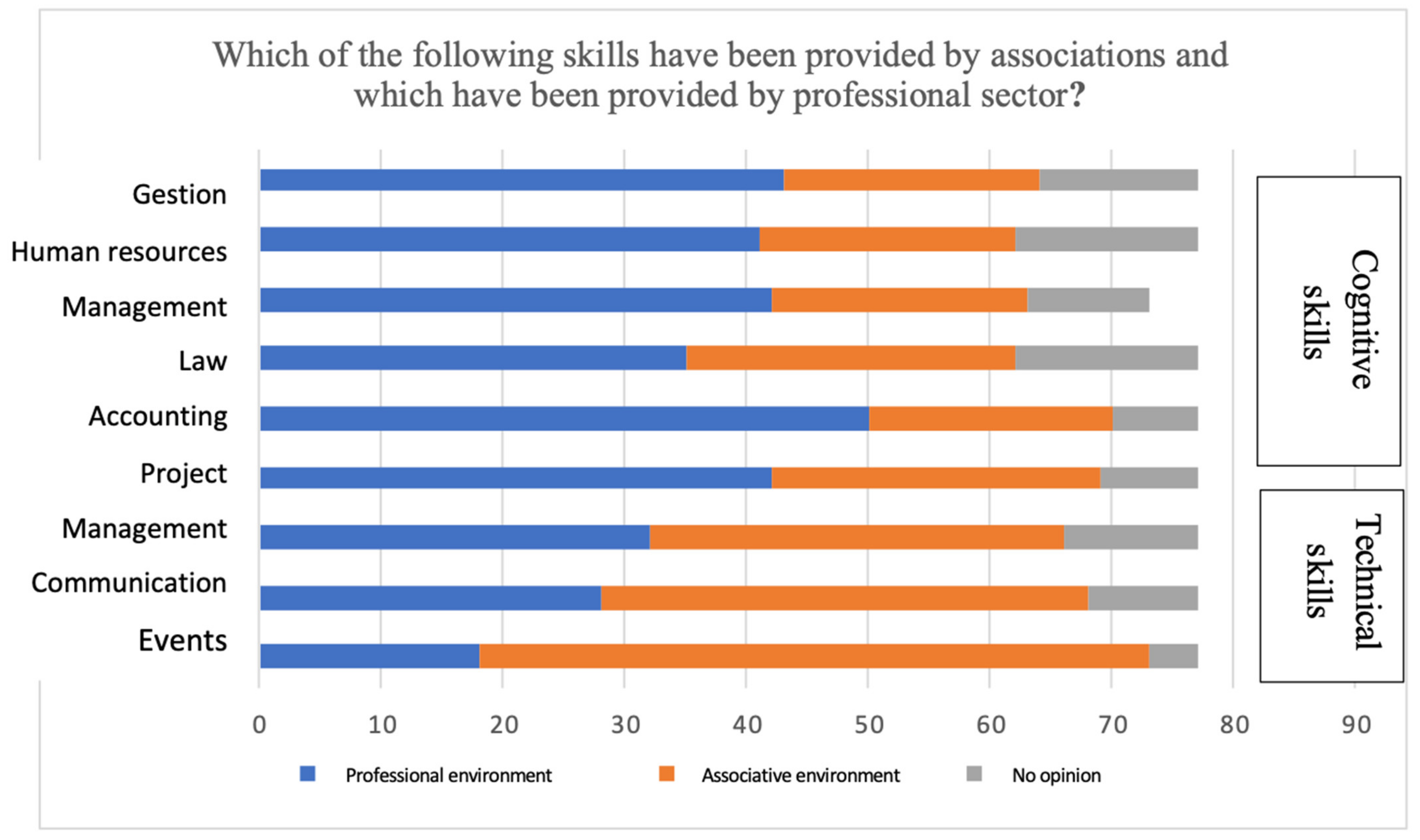

Our study confirms the results of previous investigations in terms of skills. A large majority of our respondents stated that NPOs today require more skills than before (more than 80% make this connection). The most sought-after areas of expertise are administration (22.8%), management (19%), setting up projects and seeking the corresponding funding (17.7%) and communication (16.5%). One of the questions in our interviews was about the source of the skills applied by the volunteers: are they acquired during volunteering experience, or are they acquired during a professional career? It is interesting to note that a majority of the skills come from the professional world and are then applied in the NPO (Figure 2 below).

Figure 2.

Source of skills mobilised by volunteers in NPOs.

The stacked columns in Figure 2 show that, for our interviewees, most of the managerial, administrative (administration, HR management, management, accounting) and IT skills were acquired via professional experience, and then mobilised into a non-profit environment. Only the more technical skills relating to project management, communication and event organisation were acquired directly through a volunteer situation.

Referring to the various typologies of competencies proposed in the social sciences [69,70,71], Morlaix [72] explained that there are three main types of competencies: cognitive competencies (knowledge that enables the understanding of situations and the means to solve the problems they pose), technical competencies (know-how) considered as “skills necessary to perform a task” [73] (p. 109), and behavioural competencies (social skills), which are also social competencies. In our case, it appears that it is the so-called cognitive skills that originate primarily from the professional world, and are then imported into the non-profit field. They are those that allow a global and contextualised interpretation of the non-profit operation and contribute to the evolution of the NPO in its economic model. These developments could explain the changes in the structure and operation of NPOs. The proliferation of events, marketing, sponsorship and merchandising services, which all appear in the organisational charts, demonstrate the entrepreneurial approach adopted by NPOs. As Ion [74] and Bernardeau-Moreau [75] pointed out, this increased demand for skills is not without consequences for the least qualified volunteers, who may feel that they are hidden away in menial tasks that are easy to carry out. For Demoustier [76] (p. 108) and Chauvière [77], cited by Tardif Bourgoin [78] (p. 18), the professionalisation of non-profit organisations accentuates a form of “qualitative differentiation”, with the enhancement of managerial, accounting and administrative skills tending to favour the most experienced volunteers, who are integrated into the economic and administrative circuits to the detriment of all others.

4. Discussion and Conclusions: Isomorphic Forms of Professionalisation

When we questioned the volunteer leaders in our sample about the development of their non-profit organisation, their analyses were similar to those of researchers [6,79,80,81,82] in that a form of isomorphism seems to work, and results in the operation of non-profit organisations becoming closer to that of the entrepreneurial model. How does it come into being and what form does it take? As we have tried to show in our empirical study, we believe that the isomorphism of sports NPOs is characterised by the need for independent funding, diversification of activities, the search for innovation and the increased need for skills derived from professional experience.

Caillé [83] (p. 10) explained that, in the field of NPOs, institutional isomorphism reflects the need for these organisations to find their own means of subsistence in order to limit their dependence on public authorities that withdraw and companies that compete. Although NPOs have tended to adopt an entrepreneurial method of management, it is with a view to increasing their financial autonomy in order to cope with cuts in public subsidies and reduce the uncertainty of the environment in which they operate. This results in an increase in its own revenues from the public sector, but also, and above all, from private services. This trend has been noted in several international studies. The adoption of economic models pushes sports NPOs to increase their own funds and reduce their dependence on public bodies [30,38,40]. In the case of France, there has accordingly been a change in the nature of this revenue. The share of revenues from internal activities (public orders, miscellaneous services) increased from 49% in 2005 to 61% in 2011 and 66% in 2017 [84]. Ruchaud and Bardout [85] observed that the distribution of revenues between the public and private sectors increased from 63% and 37% in 2002, respectively, to 51% and 49% in 2007. In the field of sports, the ratio is similar, at 33% and 67%. According to Tchernonog [86] (p. 10), revenue comes mostly from the sale of services (sale of related products, organisation of paid events, miscellaneous services), which increased by 6.3% between 2005 and 2011. This increase in public and, above all, private revenues correlated with a steady decline in state and municipal public subsidies. From 2011 to 2017, the share of state public subsidies fell from 34% in 2011 to 20% in 2017 (Tchernonog and Prouteau, 2019). From 2005 to 2017, the share of municipal subsidies in NPO budgets also declined from 15.2% to 11.5% [87] (p. 536). It is also worth noting that this decrease in public aid tends to be compensated, as Cottin-Marx highlighted [15] (p. 137), by a very significant increase in public orders (partnership contracts, service contracts, public contracts). In 2005, only 7% of NPOs responded to calls for tenders; however, in 2011, the figure was 23% [86]. In reality, this very significant strengthening of tendering procedures reflects a call for competition between NPOs and companies [88] (p. 79), which, by investing in the public and social domain, “monetises” this competition [89] (p. 116). The consequence is the emergence of a particular form of NPO: the “non-profit enterprise”, characterised by a growing share of employees. Recruited by volunteer leaders, these employees are responsible for negotiating contracts (particularly public service delegation contracts) and increasing revenue from their own income.

Each time, writes Enjolras [44] (p. 63), that non-profit organisations are put in competition with for-profit organisations, a trend of institutional isomorphism develops. From this group and institutional perspective, institutional isomorphism therefore reflects a convergence of behaviours between organisations developing within the same field that share the same audience, products and services. Hoarau and Laville [10] (p. 23) wrote that this process of homogenisation encourages organisations to imitate already viable structures and techniques, such as funding procedures, product and service diversification, and the use of innovation. Under the influence of “competitive mimicry” [90], NPOs, at least those that have the means to do so, try to play on an equal footing with companies by mobilising the same administrative and management tools. As explained by Ospital and Templier [91], for NPOs, the integration of management logic results in importing management practices and tools. They need to “be competitive” [45] (p. 282). Between the non-profit organisation and the member, and between the non-profit organisation and the public institution, it appears that the relationship is more contractualised, insofar as the member purchases a service and the public institution entrusts the management of its facilities to an NPO. In this “culture of contract” [92] (p. 165), the NPO becomes a true service provider [15]. In a general context of empowerment and competition, all these studies ultimately conclude that there is a growing and rapid privatisation of NPO resources and, more generally, a significant strengthening of managerial, and also competitive, logic modelled on the entrepreneurial model.

This isomorphism of NPOs with the business world is also made possible by hiring volunteers who are better trained and better adapted to new requirements. This trend has been observed by many authors in Europe and America [40,41]. In France, national surveys highlight the growing importance of skills in the voluntary sector. According to Bazin et al. [93], nearly 80% of volunteer leaders wish to renew or strengthen their management teams through the provision of skills, with initial or in-house training being seen by the majority as an indispensable means of gaining access to responsibilities. For Tchernonog and Prouteau [84], the rise in the level of competence is measured by an increase in the share of senior socio-professional categories (business leaders, senior managers, self-employed professions) in presidencies of non-profit organisations. Indeed, according to the aforementioned authors, this share increased from 29% in 2011 to 31% in 2017. The skills mobilised are mainly management, legal and communication skills. Thus, as a result of an increasingly managerial regulation of NPOs, volunteer experiences are increasingly perceived as activities that require and generate administrative and managerial skills. In the general context of withdrawal of the public player, the managerial dimension is characterised by an injunction to functional efficiency and rationalisation. These findings explain the emergence of professional volunteers to replace volunteering as a hobby and recreation. This “marketing” of the non-profit world thus transforms the activity of the volunteer into a profession [89], with its standards, obligations of result, and requirements similar to the entrepreneurial model. From this point of view, the work on business managers and the influence of observable and unobservable attributes [94,95,96] is useful for understanding developments in the associative world. Indeed, while observable attributes such as gender and age seem to be little influenced by the process of isomorphism (volunteer leaders remain mostly men aged 50 and over), unobservable attributes such as skill level seem to illustrate the process of professionalization. The skills for managing associations are also useful for managing businesses.

Although isomorphism appears to affect the NPOs that we interviewed, does our study make it possible to ultimately identify a particular form of isomorphism? As we mentioned earlier, studies on this sport conclude on varied forms of isomorphism. Hinings, Slack and Thibault [33] analysed the professional evolution of sports organisations from the perspective of normative isomorphism. O’Brien and Slack [49] mobilised the concepts of mimetic isomorphism to explain the transition from a hobby logic to a professional logic in the context of English rugby. For Hoye et al. [50], there is no doubt about the situation of institutional isomorphism in sports NPOs. In Canada, Australia, New Zealand and the United Kingdom, the majority of sports organisations adopt very similar managerial and administrative governance frameworks [50] (p. 166). Stenling and Fahlén [51] tried to demonstrate how the institutional context of the Swedish sports movement has undergone normative isomorphism under the influence of the dominant logics that prevail in this field. Vos et al. [52] noted the effects of coercive isomorphism imposing standards and operating methods in the instrumentalisation of sports clubs by the Flemish government. As for Stenling and Sam, professionalisation places normative and mimetic isomorphic pressures on sports NPOs [51] (p. 580). Following our analysis, we believe that mimetic isomorphism is the best mechanism for characterising NPOs in France. There are at least two reasons for this. The first reason is that the government has opted for a less centralised and more liberal policy since the 1990s, by delegating management and support in the non-profit world to sports federations (these federations are in power because they carry out a public service task), and above all, to territorial authorities (municipalities and departments). Government standards are followed by a contractualisation policy for the relations between NPOs (and also companies that invest in the social and public field) and local public actors. The latter increasingly aim to delegate the organisation of their public service to the service providers who are deemed to be the most effective. These service providers are non-profit, and are also, most importantly, entrepreneurial (this is the case for the delegated management of sports facilities, such as swimming pools, leisure centres and sports complexes). The result is to create a climate of very high uncertainty, thus disrupting the traditional functioning of sports NPOs. The second reason is derived from the first. In this more liberal and competitive area, uncertainty about the future or even the survival of non-profit organisations encourages them to imitate other, dominant organisations. This isomorphism occurs mainly in the organisational field. Dimaggio and Powell specified that the field only exists as long as it is institutionally defined and established by specialised organisations that govern, organise and standardise it [55] (p. 148). It thus forms a group of organisations that offer the same products and services and have similar funding sources and local ties [64]. By moving closer to the field of commercial sports organisation, sports NPOs use the same administrative and management tools to ensure the profitability of the economic model, use similar software and communication supports to attract participants and consumers, and employ staff who have managerial, administrative, accounting and IT skills (in the case of NPOs, imported from the professional sector). One of the theories posited by DiMaggio and Powell [55] is that the more an organisational field is subject to the same limitations and relies on the same supports for its vital resources, the higher the level of isomorphism. Scott adds that each field is linked to a regulatory system that is unique to it and plays a stabilising role that is all the more important because the environment in which it operates appears to be increasingly uncertain [64] (pp. 173–174). Authors such as Hawley [63] also demonstrate that to combat ongoing and increasingly rapid changes in their environment, organisations may be obliged to follow the trend and mimic their most successful counterparts in the field. Isomorphism is therefore the consequence of formal and informal legal, accounting, bureaucratic and administrative pressures, which lead some organisations to align both their structure and their operating model with those of other larger and more influential organisations operating in the same field. While smaller sports NPOs tend to group together (clusters of local sports clubs have become more and more common in the last 15 years), others tend to follow the management and professional model used by organisations that are larger, better-equipped, and have higher-performance tools and better-skilled executive managers. The consequence, as shown by public regulation, is an evolution of the legal model of associations. Those that have become highly professionalized are increasingly assimilated to “associative enterprises”. Some of their activities are now for profit and commercial purposes. This also explains the creation of associations with special statutes: part non-profit, part business. It is likely that, in the short term, some associations will lose their non-profit status and enter into direct competition with commercial organizations.

However, our study has limitations that are important to note. The low number of non-profit organisations analysed, the work gathering qualitative data by students, the population limited to only volunteer leaders, and the choice of the northern French region, which cannot represent all sports established on a national level, are restrictions that reduce the heuristic aspect of our study’s conclusions, and put into perspective the general and conceptual range of our study. Nevertheless, our study is consistent with investigations undertaken by other researchers that show that there is now a firmly established link between NPOs and commerce, and between volunteering and skills. Isomorphism is becoming more prevalent amongst NPOs in response to the increased complexity of administrative and managerial tasks, the expanded use of technology in facilitation and support, market liberalisation, and decreased public sector spending, which have obliged non-profit managers to find alternative sources of funding. For Laville and Sainsaulieu, institutional isomorphism brings us closer to the neo-liberal worldview [92] (p. 163), in that administrative and managerial requirements are increasingly seen as a prerequisite for thought and action in the social sphere [97] (p. 115). This non-profit and volunteer streamlining is symptomatic of a general movement that is leading to a blurring of the boundaries between the non-profit field and the entrepreneurial field, all for the sake of greater efficiency and success [98] (p. 373). As we have endeavoured to highlight, these transformations, both in the non-profit field and elsewhere, come at a price. Not only have we seen that those with the least training tend to be given operational and logistical tasks, but they also bring the non-profit aims into question. For Laville and Sainsaulieu [92], this basic shift consequently muddies the true nature of the non-profit project, given the apparent difficulties encountered in reconciling the managerial adaptation of NPOs with the values on which they are based, and which justify their existence. Now more than ever, the question to be asked is: will volunteers manage to reconcile the need for management with the non-profit project, “real capital accumulated over the course of its history” [92] (p. 372)? Further research is needed to clarify this point. Such research will undoubtedly open and fuel the burgeoning debate among non-profit leaders concerning safeguarding the social mission of NPOs while ensuring their future survival.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

List of sports NPOs and cities interviewed.

Table A1.

List of sports NPOs and cities interviewed.

| Sports NPOs | Number of Members | Sport Level | Number of Volunteers/Leaders | Number of Employees |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Athletics club | 87 | Departmental | 8/8 | 2 |

| Badminton club | 200 | National | 14/8 | 3 |

| Football club | 200 | Regional | 16/8 | 2 |

| Handball club | 243 | Regional | 15/6 | 2 |

| Football club | 250 | Regional | 15/11 | 2 |

| Fitness club | 280 | Departmental | 17/10 | 1 |

| Fitness club | 280 | Departmental | 12/7 | 1 |

| Ice hockey club | 300 | National | 16/6 | 2 |

| Rugby club | 373 | National | 20/10 | 2 |

| Tennis club | 450 | Regional | 26/12 | 14 |

| Multi-sport club | 1350 | National | 45/12 | 3 |

| Regional volleyball league | 16566 | Regional | 44/12 | 3 |

| Regional basketball league | 47835 | Regional | 45/9 | 12 |

| Regional Olympic sports committee | 83345 | Regional | 12/6 | 8 |

Footer: Cities. Ronchin/Bourges/Béthune/Wattignies/Wasquehal/Avion/Lezennes/Lomme.

Notes

| 1 | The acronym NPO stands for non-profit organisation. In France, these are commonly known in French as “associations” (non-profit organisations) as governed by the statutory framework of the 1901 law. In this article, we use the term “non-profit organisation”. |

References

- Kikulis, L.; Slack, T.; Hining, B.; Zimmermann, A. A structural taxonomy of amateur sport organizations. J. Sport Manag. 1989, 3, 129–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, P.; Rose, N. Production, identity and democracy. Theory Soc. 1995, 24, 427–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koski, P.; Heikala, J. Professionalization and organizations of mixed Rationales: The case of Finnish national sport organizations. Eur. J. Sport Manag. 1998, 1, 7–29. [Google Scholar]

- Barthélémy, M. OBNL: Un Nouvel Age de la Participation? Presses de Sciences Po.: Paris, France, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez, J.M. Liability and volunteer organizations: A survey of the law. Nonprofit Manag. Leadersh. 2003, 14, 151–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardeau Moreau, D. Sociologie des Fédérations Sportives; L’Harmattan: Paris, France, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Broadbridge, A.; Parsons, E. Managing change in nonprofit organizations: Insights from the UK charity retail sector. Voluntas 2004, 15, 227–242. [Google Scholar]

- Ashcraft, K. Resistance through consent? Occupational identity, organizational form, and the maintenance of masculinity among commercial airline pilots. Manag. Commun. Q. 2005, 19, 67–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesh, S. The myth of the non-governmental organization: Governmentality and transnationalism in an Indian NGO. In International and Multicultural Organizational Communication; Cheney, G., Barnett, G., Eds.; Hampton Press: Creskill, NJ, USA, 2005; Volume 7, pp. 193–219. [Google Scholar]

- Hoarau, C.; Laville, J.-L. La Gouvernance des OBNL; Erès: Paris, France, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, H.; Powell, W.W. The rationalization of charity: The influences of professionalism in the nonprofit sector. Adm. Sci. Q. 2009, 54, 268–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Simonet, M. Le Travail Bénévole: Engagement Citoyen ou Travail Gratuit? La Vie des Idees: Paris, France, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ganesh, S.; McAllum, K. Volunteering and professionalization: Trends in tension. Manag. Commun. Q. 2011, 26, 152–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aberg, P. Managing expectations, demands and myths: Swedish study OBNL caught between civil society, the State and the market. Voluntas 2013, 24, 537–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cottin-Marx, S. Gouverner par l’accompagnement. Quand l’état professionnalise les OBNL employeuses. Marché Organisations 2019, 3, 135–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauthier, C. De bonnes raisons de résister à la réforme de l’éducation au Québec. Éducation Can. Tor. 2008, 48, 46. [Google Scholar]

- Derosier, B. What is the Future for the Position of the NPO Leader? Running an NPO Today: Voluntary or Paid Work? October Following the National Conference on Community Projects on 21 February 1999. 2005. Available online: https://www.assemblee-nationale.fr/11/rapports/r3113.asp (accessed on 15 August 2021).

- Ion, J. Clubs d’Athlétisme et Professionnalisation. Une Etude de Cas, La Professionnalisation des Organisations Sportives, Nouveaux Enjeux, Nouveaux Débats (Textes Réunis et Présentés par Chantelat P.); L’Harmattan: Paris, France, 2001; pp. 241–254. [Google Scholar]

- Parsons, T. The Professions and Social Structure. Soc. Forces 1939, 17, 457–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hugues, E. Men and Their Work; The Free Press of Glencoe: New York, NY, USA, 1938. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, H.S. Le Travail Sociologique: Méthode et Substance; Academic Press Fribourg–Ed. Saint Paul.: Fribourg, Switzerland, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Dubar, C. La Socialisation: Construction des Identités Sociales et Professionnelles; Armand Colin: Paris, France, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Abbott, A. The System of the Professions: An Essay of the Division of Expert Labour; Chicago University Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Paradeise, C. Les professions comme marchés du travail fermés. Sociol. Sociétés 1988, 20, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Demazière, D.; Gadéa, C. Sociologie des Groupes Professionnels, Acquis Récents et Nouveaux Défis; La Découverte: Paris, France, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Freidson, E. Professional Powers: A Study of the Institutionalization of Formal Knowledge; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Bucher, R.; Strauss, A. Professions in Process. Am. J. Sociol. 1961, 66, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr-Saunders, A.M.; Wilson, P.A. The Professions; Oxford University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1933. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, J.R.; Mason, D.S.; Washington, M. Institutional pressures, government funding and provincial sport organizations. Int. J. Sport Manag. Mark. 2009, 6, 128–149. [Google Scholar]

- Dowling, M.; Edwards, J.; Washington, M. Understanding the concept of professionalization in sport management research. Sport Manag. Rev. 2014, 17, 520–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardeau-Moreau, D.; Collinet, C. Les Educateurs Sportifs en France depuis 1945: Question sur la Professionnalisation; PUR, Des Sociétés: Rennes, France, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Marchal, E. L’Emploi dans le Secteur Associatif CEE, Dossier n°11. 1984. Available online: https://www.cairn.info/revue-francaise-des-affaires-sociales-2002-4-page-97.htm (accessed on 15 August 2021).

- Hinings, C.R.; Slack, T.; Thibault, L. Professionalism, structures and systems: The impact of professional staff on voluntary sport organisations. Int. Rev. Sociol. Sport 1991, 26, 33–44. [Google Scholar]

- Inglis, S. Roles of the board in amateur sport organizations. J. Sport Manag. 1997, 11, 160–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kikulis, L.M.; Slack, T.; Hinings, C.R. Toward an understanding of the role of agency and choice in the changing structure of Canada’s national sport organizations. J. Sport Manag. 1995, 9, 135–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horch, H.D. Self-destroying process of sports clubs in Germany. Eur. J. Sport Manag. 1998, 5, 46–58. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, L.; Minikin, B. Developing strategic capacity in Olympic sport organizations. Sport Bus. Manag. Int. J. 2011, 1, 219–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shilbury, D.; Ferkins, L. Professionalization, sport governance and strategic capability. Manag. Leis. 2011, 16, 108–127. [Google Scholar]

- Nichols, G.; Padmore, J.; Taylor, P.; Barrett, D. The relationship between types of sports club and English government policy to grow participation. Int. J. Sport Policy Politics 2012, 4, 187–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayle, E.; Robinson, L. A framework for understanding the performance of national governing bodies of sport. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2007, 7, 249–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brudney, J.L.; Meijs, L.C. Models of VolunteerManagement: Professional Volunteer Program Management in Social Work, HumanService Organizations: Management. Leadersh. Gov. 2014, 38, 297–309. [Google Scholar]

- Bernardeau-Moreau, D. Formation, diplômes et compétences de l’entraîneur sportif. RJES 2017, 180, 20–24. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, M. Economie et Société; Plon, Agora les Classiques: Paris, France, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Enjolras, B. Comment expliquer la présence d’organisations à but non lucratif dans une économie de marché?: L’Apport de la théorie économique. Revue Française d’Economie 1995, 10, 37–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrella, F.; Richez-Battesti, N. Régulation de la qualité dans les services à la personne en France: L’Economie sociale et solidaire entre innovation et isomorphisme ? Manag. Avenir 2010, 35, 273–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbruggen, S.; Christiaens, J.; Milis, K. Can resource dependence and coercive isomorphism explain nonprofit organizations’ compliance with reporting standards? Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2011, 40, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Leiter, J. An industry fields approach to isomorphism involving Australian nonprofit organizations. Voluntas 2013, 24, 1037–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.W.; Rowan, B. Institutionalized organizations: Formal structure as myth and ceremony. Am. J. Sociol. 1977, 83, 340–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- DiMaggio, P.J.; Powell, W.W. The Iron Cage Revisited: Institutional Isomorphism and Collective Rationality in Organizational Fields. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1983, 48, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Scott, W.R. Institutions and Organizations; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Bensedrine, J.; Demil, B. L’Approche néo-institutionnelle des organisations. In Repenser la Stratégie; Laroche, H., Nioche, J.P., Eds.; Vuibert: Paris, France, 1998; pp. 85–110. [Google Scholar]

- Subbary, R.; Greenwood, R.; Hinings, C.R. Theorizing Change: The Role of Professional Associations in the Transformation of Institutionalized Fields. Acad. Manag. J. 2002, 45, 58–80. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver, C. Strategic responses to institutional processes. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1991, 16, 145–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ménard, C. L’Approche néo-institutionnelle: Des concepts, une méthode, des résultats. Cahiers d’Economie Politique 2003, 44, 103–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Leiter, J. Structural isomorphism in Australian nonprofit organizations. Volunt. Int. J. Volunt. Nonprofit Organ. 2005, 16, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvidson, M. Change and Tensions in Non-profit Organizations: Beyond the Isomorphism Trajectory. Voluntas 2018, 29, 898–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hawley, A. Human ecology. In International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences; Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 1968; pp. 328–337. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, W.R. Unpacking institutional arguments. In The New Institutionalism in Organizational Analysis; Powell, W.W., Ed.; Chicago University Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1991; pp. 164–182. [Google Scholar]

- Slack, T.; Hinings, B. Institutional pressure and isomorphic change: An empirical test. Organ. Stud. 1994, 15, 803–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, D.; Slack, T. The emergence of a professional logic in English rugby union:The role of isomorphic and diffusion processes. J. Sport Manag. 2004, 18, 13–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoye, R.; Smith, A.; Westerbeek, H.; Stewart, B.; Nicholson, M. Sport Management: Principles and Applications; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Stenling, C.; Fahlén, J. The order of logics in Swedish sport—Feeding the hungrybeast of result orientation and commercialisation. Eur. J. Sport Soc. 2009, 6, 121–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vos, S.; Breesch, D.; Késenne, S.; Van Hoecke, J.; Vanreusel, B.; Scheerder, J. Governmental subsidies and coercive pressures. Evidence from sport clubs and their resource dependencies. Eur. J. Sport Soc. 2011, 8, 257–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagel, S.; Schlesinger, T.; Bayle, E.; Giauque, D. Professionalisation of sport federations—A multi-level framework for analysing forms, causes and consequences. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2015, 15, 407–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, G.; Wicker, P.; Cuskelly, G.; Breuer, C. Measuring the formalization of community sports clubs: Findings from the UK, Germany and Australia. Int. J. Sport Policy Politics 2015, 7, 283–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenling, C.; Sam, M. Professionalization and its consequences: How active advocacy may undermine democracy. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2020, 20, 577–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Le Roux, N. Évolution des connaissances et perspectives de recherche sur l’emploi et la professionnalisation dans le secteur du sport. In Management du Sport: Actualités, Développements et Orientations pour la Recherche; Bouchet, P., Pigeassou, C., Eds.; AFRAPS: Montpellier, France, 2006; pp. 13–141. [Google Scholar]

- Lochard, Y.; Trenta, A.; Vezinat, N. Quelle Professionnalisation Pour le Monde Associatif? Entretien avec Matthieu Hély. La Vie des Idées, 25 Novembre 2011. ISSN 2105-3030. Available online: http://www.laviedesidees.fr/Quelle-professionnalisation-pour.html (accessed on 25 November 2011).

- Iribane, P. La Logique de l’Honneur: Gestion des Entreprises et Traditions Nationales; Seuil: Paris, France, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Stroobants, M. La production flexible des aptitudes. Educ. Perm. 1998, 2, 11–21. [Google Scholar]

- Stasz, C.; Brewer, D.J. Academic Skills at Work: Two Perspectives; National Center for Research in Vocational Education: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Morlaix, S. Les compétences sociales à l’école primaire : Essai de mesure et effets sur la réussite. Carrefours de l’Education 2015, 2, 183–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sellenet, C. Approche critique de la notion de «compétences parentales». La Revue Internationale de l’Education Familiale 2009, 2, 95–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ion, J. Que Sont les Dirigeants Associatifs Devenus? L’Université de Saint-Etienne: Saint-Eienne, France, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Bernardeau-Moreau, D. Professionnalisation des Bénévoles: Compétences et référentiels. SociologieS Théories et Recherche. 2018. mis en ligne le 13 mars 2018. Available online: https://doi.org/10.4000/sociologies.6758 (accessed on 15 August 2021).

- Demoustier, D. Le bénévolat, du militantisme au volontariat. Revue Française des Affaires Sociales 2002, 4, 97–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauvière, M. Problématique pour comprendre la transformation des enjeux professionnels dans l’action sociale. In Proceedings of the Second Congress of AFS, Bordeaux, France, 5–8 September 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Tardif Bourgoin, F. Vers une Professionnalisation du Bénévolat? Un Exemple dans le Champ de l’éducation Populaire; Le Travail du Social; L’Harmattan: Paris, France, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Chifflet, P. Les fédérations sportives, politiques et stratégies [Sports federations, policies and strategies]. In Proceedings of the Sciences Sociales et Sports. Etats et Perspectives [Social and Sports Sciences: States and Perspectives], Strasbourg, France, 13–14 November 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Suaud, C. Le Sport dans Tous ses Pouvoirs, l’Espace des Pouvoirs du Sport. Les Cahiers de l’Université Sportive d’été; MSHA: Arlington, VA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Chantelat, P. La Professionnalisation des Organisations Sportives, Nouveaux Enjeux, Nouveaux Débats [The Professionalization of Sports Organizations, New Challenges, New Debates]; Espaces et Temps du Sport; L’Harmattan: Paris, France, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Gasparini, W. Sociologie de l’Organisation Sportive; La Découverte, Repères: Paris, France, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Caillé, A. Présentation. Rev. Du MAUSS 2003, 1, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tchernonog, V.; Prouteau, L. Le Paysage Associatif Français, 3rd ed.; Juris; Dalloz: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ruchaud, S.; Bardout, J.-C. Guide des Dirigeants d’OBNL, 5th ed.; Juris Editions; Droit Pratique et Correspondance: Paris, France, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Tchernonog, V. Les OBNL Entre Crise et Mutations: Les Grandes Evolutions; ADDES: Paris, France, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Prouteau, P.; Tchernonog, V. Évolutions et transformations des financements publiques des associations, École nationale d’administration. Revue Francaise d’Administration Publique 2017, 3, 531–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousi, G. La professionnalisation des OBNL en questions. In Les Cahiers Millénaires; Les Cahiers Millénaires: Grand Lyon, France, 2005; pp. 77–84. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrand-Bechmann, D. Le Bénévolat: Au Bénévole Inconnu; Dalloz, Juris Editions: Paris, France, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hannan, M.T.; Freeman, J. Obstacles to comparative studies. In New Perspectives on Organizational Effectiveness; Goodman, P.S., Pennings, J.M., Eds.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Ospital, D.; Templier, C. La professionnalisation des OBNL, source ou perte de sens pour l’action bénévole? Etude du cas Surfrider foundation Europe. ARIMHE RIMHE 2018, 3, 3–25. [Google Scholar]

- Laville, J.-L.; Sainsaulieu, R. L’OBNL. Sociologie et Économie; Fayard, Pluriel: Paris, France, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bazin, C.; Thierry, D.; Malet, J. La France Bénévole, 8th ed.; ADDES: Paris, France, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Coles, J.L.; Li, Z.F. An Empirical Assessment of Empirical Corporate Finance. 2019. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1787143 (accessed on 15 August 2021).

- Coles, J.L.; Li, Z.F. Managerial Attributes, Incentives, and Performance. Rev. Corp. Financ. Stud. 2020, 9, 256–301. [Google Scholar]

- Garner-Moyer, H. Gestion de la diversité et enjeux de GRH. Manag. Avenir 2006, 1, 23–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avare, P.; Sponem, S. Le managérialisme et les OBNL. In La Gouvernances des OBNL: Economie, Sociologie, Gestion; Erès: Paris, France, 2008; pp. 113–130. [Google Scholar]

- Bartoli, A. Le Management des Organisations Publiques, 2nd ed.; Management Public, Dunod: Paris, France, 2005. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).