1. Introduction

Technologies for older people are of pertinent interest to both sociologists and designers, not only due to increasingly ageing populations, but also because older people actively engage with technologies in various ways [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. This has become especially evident during the COVID-19 pandemic, where older people in many countries are encouraged to isolate themselves at home. Here, technically mediated communication is seen as one way to help older people stay connected with the outside world [

6,

7,

8,

9]. Likewise, “ageing in place” reforms and digitalization have given additional force to efforts aimed at understanding how technical applications should be designed to best address the needs of ageing populations [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14].

To design technologies that speak to the needs and requirements of older people, involving them in co-design procedures is attracting more and more popularity [

15,

16,

17,

18]. Co-design is a more recent procedure that is part of the broader discipline of participatory design (PD), and foregrounds the role of designers as equal partners to the participants [

19,

20]. One outcome of involving older people that is often emphasized in PD and co-design is “mutual learning” [

21,

22,

23]: By bringing designers together with users, participatory design may spur knowledge transfer between both groups so that members gradually learn about the corresponding experiences of each other. The implementation itself is seen as a learning process for both those who lead the design process and for those who participate. This learning can lead to competent participants, close to “expert” users [

24], who can formulate ideas and ask questions in an increasingly initiated way. However, mutual learning does not automatically result from PD activities. For innovative solutions to emerge in design, a certain degree of openness is required to be able to see things in new ways [

25]. Therefore, PD scholars argue that mutual learning is particularly successful in design environments in which both designers and participants are able to share and widen their individual perspectives, thereby enabling designers and participants to build on each other’s experiences [

21,

26].

Besides the general recognition of mutual learning as a particular outcome of design activities enabled by an open and trusting collaboration, the precise content of these learning outcomes has not received extensive attention within the PD literature. Despite recent efforts devoted to providing a deeper understanding of design practices (e.g., [

27,

28,

29]), including calls to examine the social life of methods in general practice [

30,

31,

32], we are still short of a detailed account of how co-design and learning activities are closely intertwined.

To attend to this gap, we turn to the rich and prolific literature stream on learning [

33], which has more profoundly examined the interconnectedness between learning and the contextual aspects of social practices. Lave and Wenger [

34], in their proposal of “situated learning,” show how opportunities for learning are intricately tied in with the social environments and legitimizing practices in which learning occurs. Based on their findings, they argue that learning should not be seen as an individual activity, but rather as occurring within “communities of practice.” In this view, learning is founded on the premises of participation in communities and engagement in group work, and defined by the power structures and interrelations of these communal practices. Likewise, activity theorists have underscored the collective nature of learning [

35,

36], and “social learning” has become a popular research subject that investigates how learning takes place in a co-evolutionary manner through collective engagement of designers and users [

37,

38,

39]. Taken together, these insights on learning as a social and collective practice open up new possibilities to relate design to the socio-material aspects of human and nonhuman practices, its underlying power dynamics, and arrangements [

40,

41,

42,

43,

44]. In this reading, design workshops that involve older people can be seen as particular “communities of practice” in which social learning occurs collectively, situated within localized socio-material arrangements and power relations. Investigating how learning takes place in these different contexts and social structures of design practices, hence, is a promising means to further illuminate our understanding of how design projects can be tailored to facilitate meaningful and suitable designs for older people.

Our study speaks to this need and particularly explores design workshops as communities of practices in which learning occurs, including their contextual aspects. To do so, we draw on ideas by philosopher Donald Schön [

45], whose work interrogated the role of contextual aspects for different practices. Dealing more particularly with the professional work actions of practitioners, Schön argued that much of professional work overwhelmingly focuses on technical rationality to solve problems, and thereby ignores the problem setting. He defines the problem setting as “the process in which, interactively, we name the thing to which we will attend and frame the context in which we will attend to them” (ibid p. 40, emphases original). His conclusion is that ignoring the problem setting is hampering the ability to handle complex, uncertain, unstable, and unique situations (ibid). Translating this notion into doing design today, we take the problem setting—including the practices, materials, and symbols it entails [

46,

47,

48,

49]—as crucial in framing how and what can be learned from involving older people in design.

Following Schön’s [

45] call for “reflection in action” of different “problem settings,” in this paper, we aim to explore and reflect on the problem setting in co-design workshops involving older people and other stakeholders. The main research question is: What are the outcomes of involving older people in different design settings? What significance do different problem settings have? With a particular eye on the socio-material arrangements that make up different “problem settings,” we combine our findings from four different countries with different disciplinary backgrounds and cultural views of age (Canada, the Netherlands, Spain, and Sweden), and present the analogies regarding what can be learned from involving older people in different co-design settings.

Our findings emerged out of an international collaboration in a joint research project, which we engaged in over the last three years from 2018 to 2020. It is part of the European program More Years Better Life, and includes partners from Canada, the Netherlands, Spain, and Sweden. Partners from these four countries have established “Academic Work Places” (AWPs) adapted to networks available at these universities and aiming “at bringing academics and practitioners together, on a continuous basis, to work on a common project, in order to make practice more evidence-based as well as to make academic evidence more practice-based” [

50] (p. 573). The research project, including the selection of respondents, the procedure for collection of data, confidentiality, and protection of individual integrity was approved by the Swedish Board for Ethical Vetting (2018/839-31/5), in Spain by the Ethics Committee of the Universitat Oberta de Catalunya (28 September 2018), and in Canada by the Trent University Research Ethics Board (file #25591). For the Netherlands, the funding agency ZONMW did not request additional ethical vetting (project number 9003037411).

While some partners collaborated with social movements organizing older people or older citizens in order to bring about political change, others formed ties with businesses or educational organizers. Moreover, there were differences regarding access to, and thus experiences of, digitalization. In what follows, we will outline our methodology, present our combined findings of how co-design takes place as learning in different settings, and discuss the relevance of these findings both for studies on learning and practitioners in design.

2. Methodology

2.1. Research Approach

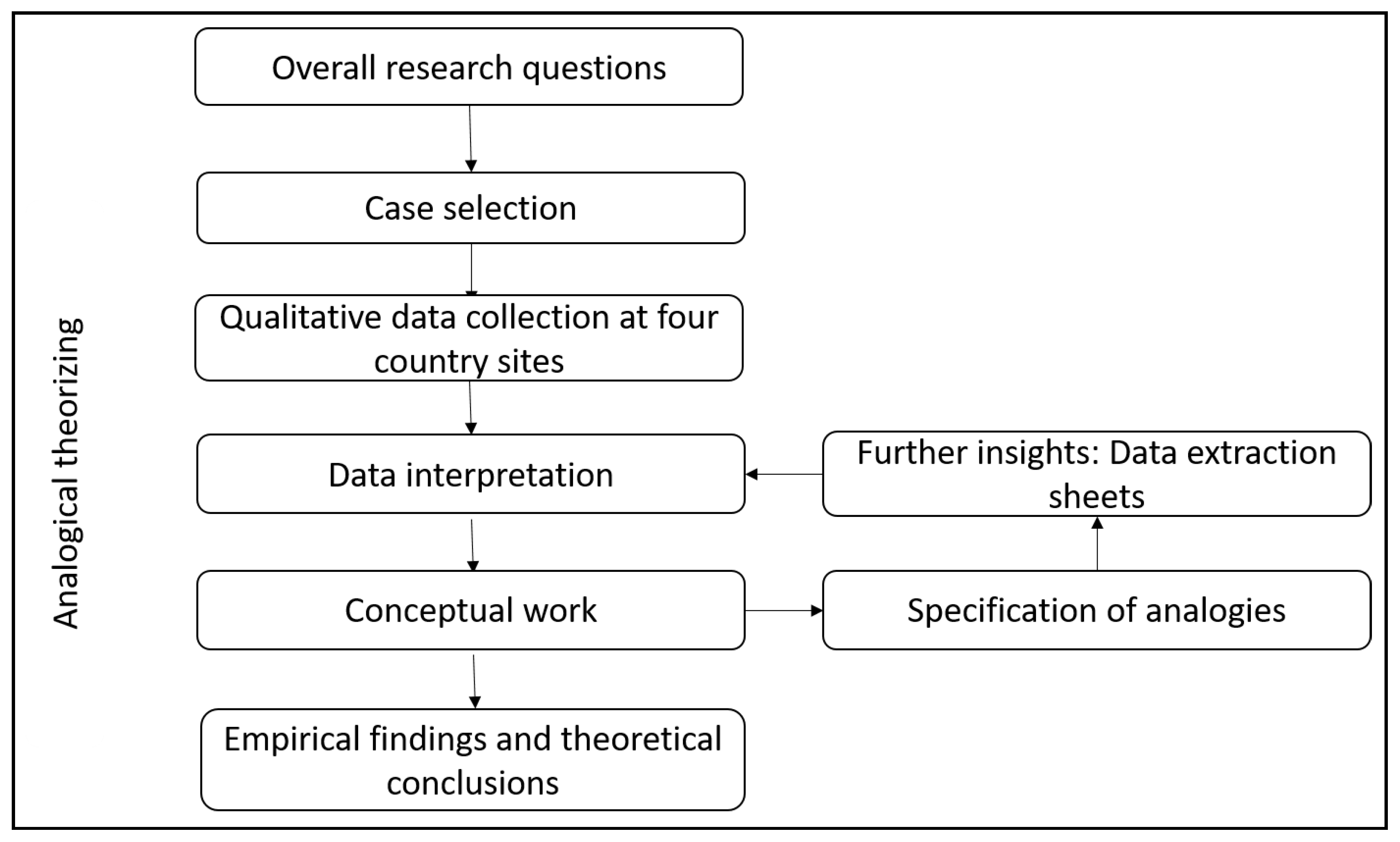

To generate findings that provide rich, in-depth insights across cultural and contextual differences, we followed a qualitative, multiple case study design spanning the sites of four different countries [

51], and adopted Vaughan’s [

52] “analogical” theorizing as an overall approach. We pursued analogical theorizing specifically because it encourages researchers to purposefully select certain settings that are relevant to the research question and to systematically search for analogies between them. In particular, we deliberately selected the different sites of the Academic Work Places to include different welfare states and care regimes—where Spain represents the Mediterranean Regime, the Netherlands represents the Continental Regime, Canada the Anglo-American Regime, and Sweden the Scandinavian Regime [

53,

54]. Our approach is based on the recognition that co-design with older people is a global phenomenon, which is “localized” into different cultural frames and institutional settings for ageing and health care. These differences provide a diverse and necessary context that makes it possible to theorize the outcomes of co-design practices across a variety of sites. Following analogical theorizing allowed us to thoroughly engage with the data generated at these different sites, and relate the insights obtained from the various cultural contexts into a more comprehensive understanding of “design as learning” that holds across the diverse socio-political settings at the “middle range” [

55,

56]. See

Figure 1 for an illustration of the research procedure.

2.2. Co-Design Procedure and Data Collection

A pilot design workshop was held at a project meeting in 2018 in Sweden. The purpose was to apply co-design and test a co-design procedure and discuss the possibilities to apply somewhat similar co-design procedures in all participating research sites [

57]. This pilot workshop included a modified version of a four-step co-design procedure: creating choices, selecting among choices, concretizing choices, and evaluating choices [

22,

58]. Following this pilot run, we added two further steps of importance: introduction and closing the workshop. As the base for co-design, the procedure tested in Sweden in 2018 was adapted to the AWPs available in the four partner countries. Hence, although we developed a particular procedure for co-design workshops, it was applied differently in practice. Different countries used modified versions of the design workshops, and one partner developed the workshop into an approach closer to focus groups, based on their particular circumstances (i.e., background, living situation, socioeconomic status, and age). To collect data on how the design workshops unfolded in practice, the local research groups were provided with data collection sheets with open questions regarding how the different stakeholder groups contributed at the different stages, which alternatives were suggested/selected/modified, which feedback the included members provided, at what the level the stakeholders were involved according to Arnstein’s [

59] ladder of citizen participation, and what could be said about the influence of the involved group in the design procedure.

For our purposes, we adapted Arnstein’s ladder of citizen participation into three levels of involvement corresponding to how much influence is given to users (see [

57]). The highest level represents how users themselves are in control, initiating and driving design to accomplish something. The intermediate level corresponds to people participating as experts on their own life situation, negotiating and collaborating with designers in partnership as consultants. The lower level refers to users functioning more as informants with the ability to comment on already made-up plans or designs, or testing prototypes. However, the data collection method was flexible to the extent that each research group could highlight and describe freely what their experiences of the design procedures were, and what the outcomes were. Hence, not all open questions were answered for each stage; rather, the local design settings [

45] were the driver in determining the content of the data that were collected [

60]. In this way, we believed we could collect data that were thoroughly grounded in—and respectful of—the social context of each case [

61].

In Canada, the design workshops were organized in a style similar to focus groups aiming at understanding which digital technologies older people use in their everyday lives, what understandings older adults associate with “technology,” and where, how, and why these technologies are used. Four sessions, recorded and averaging one and a half hours in length, were held in two cities, one in a large urban center (population 3 million) and three in a smaller city (population 80,000). Two of the sessions were held in retirement residences with participants recruited internally, and the other two sessions were held at a public library, with participants recruited through posters advertised throughout the downtown core.

In the Netherlands, the workshops were aimed at learning about older people’s everyday use of smartphones. Four sessions with four participants each were conducted in a health technology laboratory, each of which lasted a little longer than one hour. The laboratory approach adopted was based on the older people bringing their own smartphones to share their experiences. The sessions strictly followed the proposed methodology tested in the pilot, creating discussions both about everyday practices and the meaningfulness of communication using smartphone technology. The responsible organizers maintained field notes regarding the articulated experiences, practices, and happenings during these workshops.

In Catalonia, Spain, two workshops were conducted using a prototype app developed in an EU-supported project following the principles of a usability test that lasted for half an hour. The aim was to design and develop software for a prototype of a mobile application within which problems took a large part of the discussions. The workshops took place at different design stages (from instruments of data collection to answers, the results, and the final design implementations), and were observed by two researchers, focusing on how the procedure unfolded, the insights gained, and the modifications made during the design process.

In Sweden, four design workshops with four different groups of stakeholders, two with older people and two with design students and nursing teachers, were conducted. The aim was to understand what makes up meaningful digitalization in later life, including robots, smartphones, and digital home assistants by suggesting modifications that would improve these applications. The workshops took place in the settings where the participating groups normally meet and lasted between two and four hours, including a brief introduction about digitization provided by a professor at the university.

2.3. Participants and Stakeholders

In total, 14 workshops were conducted with 120 participants (44 men, 75 women, 1 undefined), distributed among four different kinds of stakeholders: older people, engineers, students in product development, and teachers of home care workers. All workshop participants gave prior consent to take part in the research and workshops. Older people included different groups ranging from 55 to 94 years old, retired for a short or long time, or part-time employed. People over 55 years were identified as belonging to the group of “older people” in order to account for the diversity and heterogeneity amongst this group [

62,

63,

64]. Choosing an age range of “older participants” is a very contested and debated issue, with arguments, for example, that numerical age should not at all be the defining feature (cf. [

65]). We chose 55 years because it allowed us to account for the heterogeneity in the older population [

62], and because it is quite frequently used as the lowest demarcation for belonging to the group of older people (cf. [

63,

64]). See

Table 1.

2.4. Data Analysis

We analyzed our data from the various different empirical settings in three stages. First, each research group analyzed the observations of their workshops locally in their country. This was done qualitatively [

66] and resulted in descriptive text reports of the observed workshops, as well as descriptive replies to open questions in the distributed data collection sheet. At the end of this step, all four partners compiled their findings and observations and sent them to the coordinating research group in Sweden. In a second step, the data were combined and again analyzed qualitatively to find meaning in the texts and identify themes and broader aspects that appeared relevant across all four countries [

60,

66]. The analysis revealed how learning was of central importance in the co-design workshops of all four partner groups, but the particular outcome of learning differed. Furthermore, it brought to the fore the relevance of the power aspects and internal dynamics underlying design workshops in creating different “problem settings” [

45] within different “communities of practice” [

34]. In a third step, with the Swedish team leading (B.F.), the research groups jointly worked together to present their empirical findings in a coherent way, emphasizing learning and how learning is related to different problem settings.

3. Design as Learning

3.1. Learning about Older People’s Everyday Experiences with Digital Technologies (Canada)

In Canada, we learned about the ways that older people use digital technologies in their everyday lives, as well as their understandings of “technology” more broadly. In Arnstein’s [

59] categorization, this could be situated at the lower level of involvement as informants. Group discussions were prompted through questions about the digital technologies most used, those they may have previously used and stopped using, whether technologies were used for health purposes, whether they felt pressure (whether originating externally or internally) to use digital technologies, how they felt about the cost of relevant technologies, and finally, which devices or applications they could imagine for the future. Overall, these discussions challenged many of the common assumptions about older people as technological laggards or as primarily concerned with family and health. The researchers found that technologies were thoughtfully and carefully considered (or resisted), and that, although technologies were used to “connect,” it was not necessarily families or caregivers they were interested in connecting with. Health was not at all a major focus in any of the four focus groups.

Participants indicated a multiplicity of apps and devices that were used: These included devices such as smart phones, iPads and tablets, laptops, e-readers, alert pendants, digital cameras, digital kilns and digital vaporizers, and apps for a range of activities, including apps for meditation and for painting-by-numbers, GPS apps for fishing, online conferencing software, and YouTube videos for learning all sorts of different skills. Conversations also revealed that participants were mindful of the impact of their participation in the digital sphere. They were careful about the amount of time they spend online, and two reasons emerged for this. First, some expressed concern that different technologies could complicate their desire to “be present” and to use their time wisely. As one participant explained,

“Maybe it’s because we’re older and I … realize how old I am … and how much of my life is gone … How much do I want to devote to sitting in front of a screen or do I want to enjoy the real world that’s out there? Because you don’t know how long it’s going to last.”

Second, there was some resistance to the labor that digital tools impose on individuals. Another participant expressed concern that digital technologies were “taking away jobs that somebody got paid for and we’re doing it for free.” Cost was also brought up on a number of occasions as an important consideration that determined which devices participants might purchase or use (having a smartphone because it is too costly to have both a landline and mobile phone, using a digital camera because it is cheaper than film) or where they might use technologies (e.g., going to the local public library to access email). Participants were also quite wary of their safety and privacy online (as well as of online misinformation) and also noted that “humanity” seemed to be missing from current iterations of digital tools.

Although a number of participants in the focus groups that took place in the public library spoke of the different apps (WhatsApp, Skype, FaceTime, or Instagram, for example) that they were using in order to stay in touch with children and grandchildren, they also used these apps to connect with broader communities, such as one participant who used video conferencing software to connect with church members across the country. Participants living in retirement residences tended to use digital technologies to stay in touch with and organize events amongst themselves in the building. This included, for example, letting each other know which person was hosting an upcoming morning coffee, and Facebook, for example, was highlighted as a resource that was used to share favorite songs or requested recipes.

One of the more surprising findings was that the use of technologies related to health concerns and risk management did not figure centrally in any of the sessions. This contrasts sharply with the emphasis on monitoring, maintaining, and/or improving health in later life in the development and marketing of technologies to older people [

10]. Only one participant spoke explicitly about health, and described how he used his iPhone to input information about his blood pressure and blood sugar levels:

“It’s the Apple app with the heart on it … it’s got incredible depth to it. You go down, vital signs and then you can put whatever you want in there. Plus your emergency information which is your blood type … But you have to be disciplined! And when your life is at stake, you’re disciplined!”

Another participant spoke about her experience with an alert pendant, suggesting that rather than increasing her sense of personal safety, it served to limit her movement out of her apartment complex as it did not, for example, work in the parking garage where there was little signal available.

Interestingly, despite demonstrating that they were quite savvy and creative with regards to digital technologies, a number of participants described themselves as “dinosaurs” or “old school,” perhaps indicative that they had internalized ageist attitudes in technological narratives about ageing and generational differences. Defying these stereotypes, facilitators were especially impressed at the mutual learning of participants that was evident as they made notes of apps mentioned by others during the discussions and as participants lingered after the end of the focus group to chat and share tech tips and recommendations with one another. The majority of participants indicated that they would have enjoyed additional time to engage in these sorts of conversations. This suggests perhaps that too few spaces exist for older people to learn from one another about technologies, and to engage in collectively imagining those that might be meaningful in their everyday lives.

3.2. Learning about Older People’s Everyday Smartphone Use (The Netherlands)

The Dutch workshops also found that the older participants mainly acted as informants according to Arnstein’s [

59] ladder. During the Dutch design workshops, participants were asked to bring their smartphones with them. All of the participants did possess a smartphone, yet as expected, their uses of them varied significantly. The workshops were designed to probe into the variety of everyday practices in which smartphones were entangled and meaningful to the participants, but even more importantly to stimulate a discussion among participants about their smartphone use practices. In this regard, it is interesting that sometimes long portions of the talk proceeded without the interviewer’s interference, which indicates that smartphones are generally a theme that the respondents find interesting. Quite often, the respondents disagreed about the usefulness of features, such as an electronic agenda, which some used and others did not. Although it is not surprising that older users, just like other age groups, are a diverse group of smartphone users, it is noteworthy that they generally seemed to have very deliberate opinions about features, even if they did not use them. So, non-use does not seem to be associated with being a laggard, but rather with deliberate decisions to be selective or to weigh the usefulness of a smartphone against other (sometimes “older”) technologies, like a paper agenda or a traditional alarm clock.

It is interesting that some of the participants were using their smartphones extensively. These participants were able to show a broad range of apps installed on their phones, were in possession of the latest smartphone models, and seemed to see smartphone use as a creative and meaningful field of activity in itself. For instance, Henk, one of the anonymized participants, is a heavy tech user that knows his iPhone (the newest generation) very well, and is not shy to brag about it. He seems to almost excessively use his phone (more intensively than many younger people or teenagers), and identifies with the excessive use as part of signifying tech savviness. The phone here seems to be a resource of identity building and an occupation (rather than a means) in itself. Henk also “volunteered” on many occasions to explain to other, less literal participants the many possibilities that a smartphone (allegedly) offers.

At such instances, the groups themselves turned into both sites of learning and sites of power relations among participants. Here, Henk seemed to be an outlier example, as he clearly dominated some discussions among participants. As he was showing the extensive app libraries and using specialized jargon to describe the uses of these apps, other participants seemed to feel slightly uncomfortable with what they perhaps then considered to be “inferior” uses of their smartphones. For instance, Ingrid, another anonymized participant—who had just told an elaborate story about how she was using WhatsApp to organize volunteer work in her local running community—became very interested in Henk’s experience, but also seemed to think that just using WhatsApp was not appropriate, and that better, probably more bespoke apps would be available for the same purpose. For us as observers, this was interesting, as it seemed to indicate that the context of the workshop as a setting explicitly dedicated to exploring smartphone use seemed to have introduced an implicit hierarchy among participants, whereby those less confident about their smartphone literacy experienced this as a deficit. It remains an interesting question whether this would have happened with younger respondents, too, or whether we were observing a form of internalized ageism, whereby incompetent smartphone use was seen as a signifier of negative effect of old age.

Regarding learning more broadly, participants also discussed their learning strategies. This further corroborated that smartphone use was both a means and an object of learning and social connectedness. For instance, many participants mentioned how they used smartphones to organize meetings of a local running club, or to support their work, for instance, as treasurer for a local sports club. However, they also mentioned how asking children and grandchildren for advice became an opportunity to stay in contact. Participants thus not only shared their experiences with using smartphones and learned from each other in this regard, but they also discussed their experiences with learning to learn. Such experiences ranged from exchanging ideas about how to avoid being overwhelmed by the many features of a smartphone, how to focus on key aspects when learning how to use it, telling stories about how learning smartphone use became a meaningful topic to discuss with grandchildren, and stories about how participants themselves had discovered usages of which their children and grandchildren were not aware.

3.3. Learning When Designing a Smartphone App (Spain)

In Spain, we observed and took part in usability tests conducted as part of the design and development of a software application. Also in this context, the participation of older people was more as informants on the lower levels of the scales, but sometimes as consultants at intermediate levels [

59]. The application stores and manages data, generated and gathered by users, for broader communal use, with appropriate privacy protections. The system allows for storing data, which is often required for processes ranging from registration to signing citizen petitions in a digital democracy platform. The system provides a connection with different websites or apps. When those websites or apps require the information stored in the application, there is the option to control which data are shared in the process. The system also allows users to register to new systems or to sign petitions anonymously. The app is part of a data activism project aimed at challenging the existing power relationships in personal data management. The usability test explored topics related to interface design but also topics related to the concept of the technology, including digital sovereignty, anonymity, privacy, and security. Most of the young participants were aware of the project previously because of their work in related topics, whereas the older participants were not aware of the project.

A first type of learning centered on the usability issues that were targeted with the tests. Here, we learned how the older people were more likely to require explicit explanations about the purpose of each feature and to require no technical language in these explanations. One of the older participants pointed at the fact that he would like guidance in the use of a new app by a “warm” expert. In general, they were more prone to identifying usability problems than most of the younger participants. Thus, although they were keen to support the idea of the app, it was difficult for them to explore it autonomously. Moreover, the design of the study shaped the possibility for participants to influence the design choices. In general, this experience helped us to appreciate how the design of the usability test, the instruments designed to collect data, and the analysis of the results shaped the possibilities of the group of participants to influence the design choices.

Beyond these usability issues, we also learned about the attitudes of participants towards this disruptive technology. The sample gave us the opportunity to see how people of different ages position themselves in a usability study. We learned about the divergences between the expectations of designers about older people and these disruptive technologies and the older people’s attitudes. Although the designers of the tools who conducted the workshop expected older people not to understand the concept of the app, the three older participants, with different levels of expertise with digital technologies and backgrounds, understood the goal of the app and identified the values of the app. They were keen to support this disruptive technology. Particularly, they worried more about privacy issues and the control of personal data than some of the younger participants and valued these aspects of the app, despite young participants being aware of the purpose of the app before the study. All participants showed less interest in security issues and in the blockchain technology used to pursue these goals. In general terms, the participants showed that they trusted the system; however, their trust in the system was more related to the context of the study than to the technology used. One of the older participants went further and argued that he would trust the system depending on the person who suggested he should use it.

In addition, we learned about the different perceptions of the people about their role in the usability test, depending on the age and the related stereotypes. Whereas middle-age participants assumed they were invited because they were target users of the app and their responses were based on their previous experiences with related technologies, young and old participants assumed they were invited to represent an underrepresented collective that requires special considerations. Older people assumed they were invited because it is more difficult for them to learn to use new technologies, and younger people because they feel they are not often involved in movements of data activism. These self-stereotypes influenced their contribution to the sessions.

3.4. Learning about How Technologies Might Be Meaningful for Older People’s Lives (Sweden)

In Sweden, the workshops were designed to allow stakeholders to articulate their perspectives about design ideas and to make suggestions for modifications of digital applications to fit later life [

25]. During these design workshops, we learned a great deal about what technological futures different stakeholders found meaningful for older people. Hence, we learned how older people had a keen interest in technological devices aimed at supporting their daily life activities. They were particularly appreciative of technologies able to link them through calls and sustain their continued life course. Examples are roles envisioned for technologies in finding lost glasses, cleaning up when something is dropped on the floor, helping with guiding lights at night, opening and closing windows, issuing reminders to take medicine, or staying connected with their networks of families, friends, and home help services. The older people particularly saw a use in smartphones to be extended to one or some of these functions, but that smart home devices and robots, they claimed, could also be used in a similar fashion. Rather than technophobes, older people presented themselves as technophiles, interested in and forward-thinking about design ideas.

We also learned from other stakeholder groups about their insights. We learned from the experiences of the design students who highlighted the benefits of telecommunication technologies for older adults to stay in touch with their families and grandchildren by sharing pictures and text messages, as well as the desirability to have a bigger screen for older adults to better navigate these technologies, as some may have problems with buttons. From the nursing teachers as experts in providing care for older people, we learned about their experiences and visions of older people and how technology might help to facilitate care for older adults. For example, their design ideas pertained to communication technology being able to translate different languages for communication between international doctors and nurses, or to support the care of older people with seeing problems through sensors attached to the arm, taking over the role of a seeing-eye dog. Overall, we gathered an abundance of design ideas for technologies for older people, ranging from technologies for older women and men, healthy and frail, lonely and social, and third and fourth age [

65]. By engaging older participants as well as other stakeholders, the diversity and heterogeneity of older adults became clear, as did plenty of design ideas; we learned about the technological interest of older people as much as about the various roles for technologies to play in older adults’ everyday lives.

From a procedural perspective, we believe that involving stakeholders in a more open manner allowed for their responses to be more explorative, based on their own life experiences and backgrounds. To be sure, we do not mean that over-simplification or a reduction of complexity of the design aspects would have enabled the participants to be meaningfully involved. As a consequence, we did not highlight the role of continued explanation or effortful guidance to support older participants during the process. In practice, such guidance appears as rather derogatory attitudes towards older people, and would have in fact limited their confidence to contribute to new technological design ideas. Rather, we mean that by providing sufficient information about current technological developments at the onset while remaining open to the responses expressed by our stakeholders, an environment was created in which the stakeholders were encouraged to disclose their own perspectives and ideas [

25]. In so doing, all anecdotes uttered were treated as relevant to the design ideas. We felt this setting was a central feature to enable learning from the involved stakeholders.

In this procedure, the retired engineers and people were mostly involved at an intermediate level, being consulted about their inputs and ideas, yet not having a say in fully embodying their ideas into specific technological objects. Their role can best be described in terms of delegation and partnership, as participating experts in their own life situation [

59]. Other stakeholders appeared to be involved at a similar level. The nursing teachers participated as consultants by contributing their own views but not primarily basing them on their own life experiences. The role of the design students also took the shape of consultants, based on their experiences with older relatives and friends. In our observations, we did not experience particularly negative stereotypes. Rather, as all participants had some connection with older people, in fact, we observed how older people were treated quite equally in terms of their interest in technologies that they already lived with. The Swedish workshops, however, did not result in concrete design objects, but purely ideational instantiations of participants’ design ideas for older people.

5. Conclusions

Unsurprisingly for sociologists, age scholars, and designers, the results from co-design depend on how workshops and other procedures are organized and who participates. This paper, however, contributes to a deeper understanding of how local socio-material arrangements affect the design process and how co-design and learning activities are closely intertwined. In particular, we have shown how power features, materials, and problem settings mattered for different learning outcomes in four different countries. Our finding that learning is not just a straightforward design result, but rather emerges out of design activities characterized by power-related aspects and socio-material assemblages, implies a central shift in thinking about co-designing for, and with, older participants. To thoroughly get hold of how different learning outcomes can be obtained in such projects, we need a more profound understanding of the implicit features of design and their accompanying practices. Future research, we hope, will further advance our knowledge of these dynamics, and illuminate the intricacies and complexities surrounding design involving older people.