1. Introduction

Irish Travellers are an indigenous ethnic minority, identified by themselves and others as a distinct group that shares a history, culture, language, customs and traditions, values and beliefs [

1]; they numbered 30,987 people in the 2016 census of the Republic of Ireland, representing 0.7% of the population [

2]. A 2017 report by the Economic and Social Research Institute (ESRI) for the Irish Human Rights and Equality Commission (IHREC) found that Irish Travellers experience a very high level of discrimination that inhibits participation in terms of education, employment and health and facilitates social exclusion [

3].

Travellers have a shorter life expectancy than the general Irish population [

2]. The Traveller advocacy group Pavee Point maintains that Travellers have poorer health status than the general population [

4]. The life expectancy for Irish men nationally in 2008 was 76.8 years, while the most recent study in 2010 predicted that Traveller men die, on average, fifteen years earlier, at 61.7 years [

1]. Among Travellers, 19.2% are unable to work due to disability; the corresponding national rate is 13.5% [

5]. The Committee on the Future of Mental Health Care acknowledged that poverty, poor housing and socioeconomic factors as well as the prejudice and discrimination endured all contribute to high levels of mental illness in the Travelling community. The suicide rate among Travellers (11%) is six times the national average [

6].

In 2008, the WHO commission on the Social Determinants of Health called for the health inequality gap to close within a generation. Worldwide, poor health and poor socioeconomic conditions go together [

7]. The poor health and socioeconomic status of Travellers should be reasons for priority access to healthcare and a high level of support [

8]; however, social stigma and discrimination are obstacles to healthcare access and societal support [

3,

9].

Historically, the Irish state has tried to assimilate Travellers. Government policies in the latter part of the twentieth century focused on assimilation into the form and norms of society [

10]. In 1960, Irish Prime Minister Charles Haughey stated, “[…] there can be no final solution of the problems created by itinerants until they are absorbed into the general community” [

11] (p. 111). These policies were unsuccessful; thus, Travellers began to be viewed as problematic for Irish society at the time, as evident in the discourse and the language used [

10]. In policy, the question of the “Traveller problem” persisted in the 1983 Report of the Travelling People Review Body and again in the 1995 Task Force Report on the Traveller Community [

10].

In the 21st century, legislative advances designated Travellers as a social group specifically protected against discrimination by equality legislation [

12]. More recent reforms reject assimilation in favour of more positive attitudes towards Traveller culture [

10]. In 2010, the EU Framework for Inclusion of Traveller and Roma groups was launched under the Europe 2020 strategy. In line with EU obligations per the strategy, Irish public policy shifted the emphasis from “integration” to “inclusion” through the National Traveller and Roma Inclusion Strategy 2017–2021 [

13]. In March 2017, the Irish government finally recognised the status of Travellers as an ethnic minority in a formal statement by Prime Minister An Taoiseach Enda Kenny, which was a significant event for the Traveller community [

13].

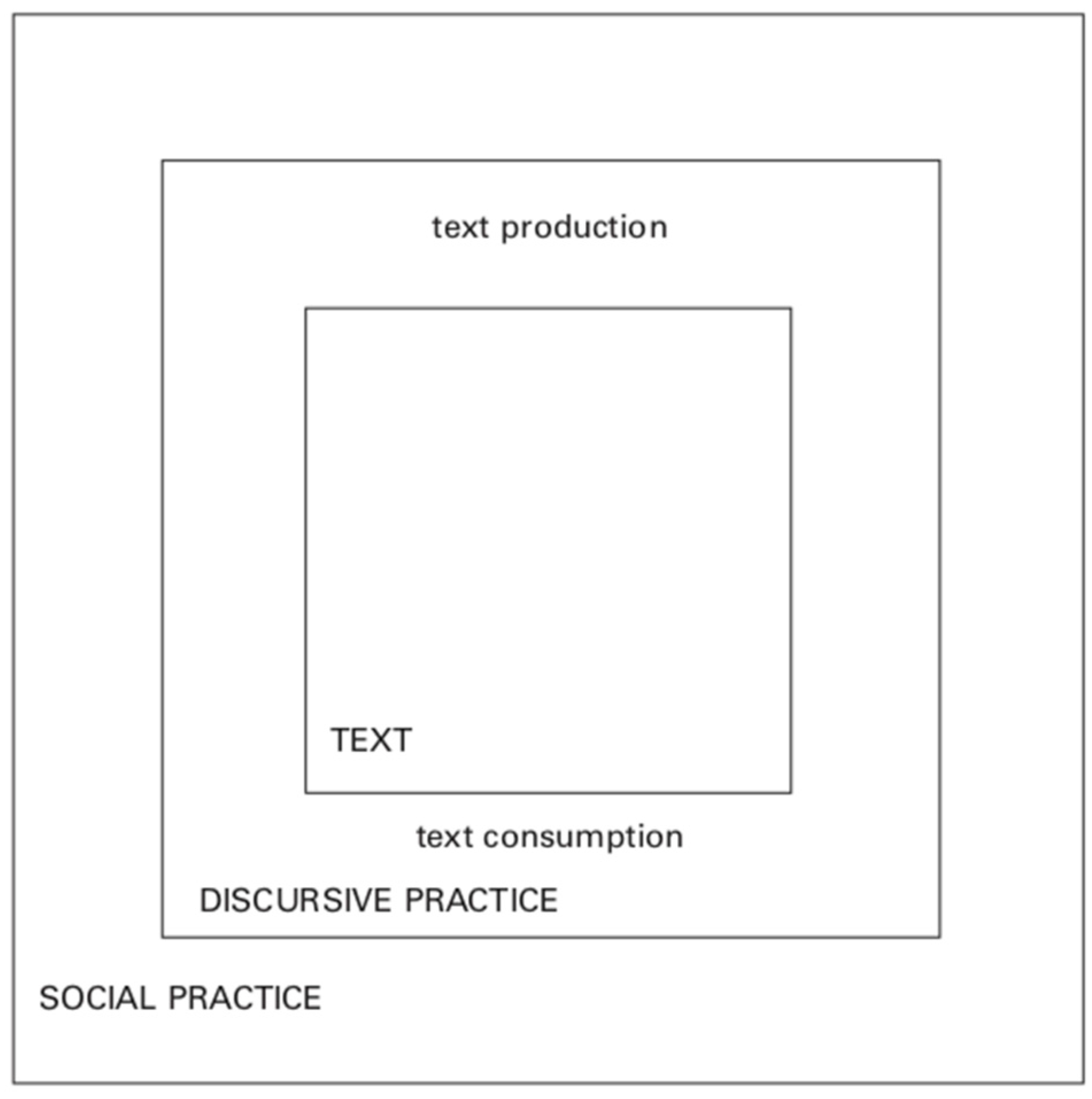

In Ireland, no critical discourse analyses (CDAs) have been carried out on the current Traveller policy. The viewpoints and ideology of the more powerful actors are disclosed in the language used to describe Travellers. Analyses of the language and the discursive practices produced in the policy documents are of particular interest for understanding the formation of discourses. The inequitable representation of Travellers in the discourse could lead to policies that poorly serve Travellers’ needs due to the lack of evidence in research and poor decisions in the policymaking process. These discourses may influence each other, allowing a misuse of power that facilitates discrimination.

The study aims to address a significant gap in the existing academic literature about how Travellers are presented in discourses by using Fairclough’s CDA framework to explore the NTRIS policy 2017–2021. Through examination of the language used to describe Travellers, this study aims to uncover how this use of language constructs reality for Travellers and seeks to determine whether this “reality” presented in policy creates unequal power relations between Travellers and broader Irish society.

4. Results

Utilising Fairclough’s CDA method of analysis, the three dimensions were analysed separately. However, they are intimately connected, and various discourses overlap in the analysis.

First, we analyse the linguistics of the text. The title of the policy on page 1, “National Traveller and Roma Inclusion Strategy 2017–2021”, conveys both a purpose of including the Traveller communities in the Irish nation and the intention of achieving strategic goals within the stated timeframe. The relevance of the word “inclusion” is described on page 17, which speaks of “a change of emphasis from integration to inclusion”. However, this new emphasis is not embodied within the core policy.

As expected from an official government publication, the language throughout the document is formal, and metaphors are not used in description. As applied to the subject matter, the formal language gives legitimacy and credibility to the policy, placing the state agency in the position of expert. Language in use creates an identity for Travellers as a separate group. This continues throughout the whole document; when referring to Travellers, the word used is simply, “Traveller”, “Travellers”. In the Foreword, the use of concrete language to describe Travellers sets up their identity as being outside of society. Although the policy makes several wider references to marginalised or disadvantaged people, such as on page 3, “those at the margins of our society”, a distinction is still created between Travellers and “other citizens” in the introductory paragraphs: “Travellers in Ireland have the same civil and political rights as other citizens under the Constitution”.

What is interesting is when the policy refers to the general population by using terms such as “settled community” and “non-Travellers”. These descriptions set up a polarity that emphasises the Traveller identity as a separate group outside of society. In relation to the prison system, page 10 states, “Traveller women were 22 times more likely to be imprisoned than non-Traveller women”. On page 11, in relation to infant mortality, the term “settled population” is used; later, on the same page, in relation to levels of education, the term “settled community” is used. On page 14, young Travellers are said to “become like the settled population”, and then, on page 24, Action 5 refers to “members of the settled population”.

Page 11 focuses on Traveller health, with a list of bullet points that catalogues the poor health choices and negative health outcomes of Travellers. The list leads to a single-statement paragraph that reads: “Travellers’ access to health services ‘is at least as good as’ that of the general population, but Travellers are less likely to attend outpatient appointments or engage with preventative services”. By grouping these texts together, it is inferred that Travellers would be less likely to make poor choices and suffer negative outcomes if, like the rest of the population, they would engage with the health services provided by the state.

In CDA, “critical” means showing connections and causes that are hidden. We apply this to the caption on page 2: “Travellers and Roma are among the most disadvantaged and marginalised people in Ireland”. On first reading, we see an expression of compassion for the plight of the marginalised. However, as we uncover the implicit meanings in the transitive effect created by the use of the adjectives “disadvantaged” and “marginalised”, the passive voice serves to present them not as actors, but as patients who are powerless, affected by the actions of others. This statement performs the ideological function of removing agency since no agent is specified. Therefore, because no one is apparently “marginalising” the victims, “disadvantaged” and “marginalised” become properties of the patient instead of processes carried out by an actor, or actors—in this case, Irish society and the state.

According to its title, the policy is committed to a specified timeframe (2017 to 2021 inclusive), and the core policy carries the title “Strategic Themes, High Level Objectives and Actions”. The overall policy is broken down into thirty-seven objectives, under which 149 actions are grouped, but no timeframe or outcome is associated with any of the actions. We find the modal auxiliary verb “should” in the title of thirty-six out of the thirty-seven objectives. Modality is the “interpersonal” aspect of grammar. Truth is a type of modality, and the author demonstrates a low level of commitment to the statement by using the medium-affinity “should” instead of a higher-affinity word, such as “shall” or “must”. For example, on page 32: “There should be a special focus on Traveller and Roma children’s rights.”, and again on page 34: “Health inequalities experienced by Travellers and Roma should be reduced”. The medium affinity of the word “should” can be interpreted as “not a requirement, but a recommendation”; therefore, it is non-binding and open to alternatives. Instead of projecting high affinity by using subjective modality (we should focus especially on...), the author uses objective modality (“There should be a special focus on...”). Here, the agent is removed, leaving it unclear whose view is being articulated. Power is often implied through the use of an objective modality.

In the policy, there is a disconnect between, on the one hand, language/subject matter and, on the other hand, visual semiosis/photographs. There are no Travellers or Roma people in any of the fourteen photographs. This seems remiss in an inclusion policy, since there is no relatable image of the people the policy seeks to include. These photos do not represent the reality for Travellers, as the majority live in urban centres. The semiosis presents a romantic image of a traditional Ireland of times gone by; it does not herald a new, inclusive Ireland.

To conclude the first stage, close analysis of the vocabulary, grammar, text structure and semiotic activity in the policy is combined to reveal the role of language in creating and sustaining the position of Travellers as a homogenous group outside society. No words or images are used to facilitate a representation of the target group based on inclusion, equality and diversity.

The second analysis is an interpretative analysis of the discourse to find hidden meaning behind the text. The point of interest is examining the relationship between the author and the reader. Here, the author uses known discourses and genres to connect with the reader.

The language of the policy discloses intertextual links to previous policies and significant reports in which the state avoided or refused to accept the ethnicity issue. Intertextuality allows us to trace a common thread that links to historical policy, where the state has previously declined recognition of the Traveller ethnicity. In 2017, the government made a well-publicised statement recognising the Traveller ethnicity. Despite this, the narrative of Travellers not being ethnically different from the general population is still evident intertextually in NTRIS 2017. Page 7 claims that the NTRIS has “no new legislative implications, creates no new rights and has no implications for public expenditure”. On page 9, the recognition of ethnicity is downplayed as a “symbolic gesture”. Here, the Minister of State appears to reassure the readership that the newly recognised Traveller ethnicity will have minimal impact on the majority, i.e., the general population.

Page 9 states that Travellers already have “legislative protections” “as a group protected”; here, we trace an intertextual link to the 1995 Report on the Taskforce for the Travelling Community that does not recognise Travellers as an ethnic group. Page 6 of that report states a need to protect “ethnic groups” and, separately, the “Travelling Community” as “a group protected”. Further intertextual evidence comes when, in 2006, the CERD recommended ethnic status for Travellers, and the Irish government’s formal response used the “protection” narrative as a means to avoid ethnic recognition, stating that Travellers have “explicit protection” and that they are not ethnically different from the rest of the general population. The response also alleged that Travellers themselves do not want ethnic recognition, basing this assertion by reference to the 1995 report. The narrative of “Travellers […] as a group protected” is seen in a common thread that traces from NTRIS 2017 back to previous policies and reports.

Again, we highlight the relationship between the author and the reader. The Minister’s foreword spans five pages and employs a promotional discourse, signalling an influence of the promotional genre, as on page 7: “This was a momentous and unprecedented decision in our country’s history”. The government reaffirms its position of authority through the promotional discourse of the foreword and the photographic imagery of Irish rural scenes throughout the policy document.

On page 3, the Minister’s foreword expresses his personal concern, stating: “I am particularly concerned by the reported rate of mental health problems...”, although such personal involvement is less evident in the remainder of the paragraph. He makes a number of statements about what needs to be done, but specificity on “who”, “what” and “when” is lacking. On the same page, he shows a higher affinity: “As a society, we cannot stand idly by.” The use of “we”, however, is exclusive rather than inclusive, as “we” cannot stand by while “they” continue to do this—again placing Travellers outside society, without agency, in the patient role.

In summary, the particular viewpoint of the elite actors does not change; therefore, the language used in the NTRIS 2017–2021 re-establishes old ideologies. On behalf of the government, the policy is authored by civil servants with a foreword by the minister. It tries to appeal to the readers in the majority, not the minority group the policy is trying to serve. The discursive practice is normative, signifying an unchanging discourse that sustains the narrative of Travellers as outsiders, and the power imbalance remains.

The third analysis is an interpretative analysis of social practice. The general objective is to assess the relationship between the policy text and the ideology underpinning it within the socio-political context. Contemporary policy represents an established order of policy making. Traditionally, government policy in Ireland is signified by the harp emblem on the title page as a symbol of the Irish government. Except for the harp, the document is textual in form, with no semiotics. By contrast, the stylistic presentation of NTRIS 2017–2021 is composed of text interspersed with visual semiotics; the foreword employs a promotional discourse that is considerably more personable than that of a conventional policy document, such as the preceding 2011 Integration strategy, which included no photography and no personal message. The promotional genre influences these two elements of semiotics and promotional discourse, as is evident in the wider social practice in what Fairclough calls the “marketisation of discourse”, a process in which the discursive practice of state and public institutions, shaped by a market discourse, treats civil society as consumers rather than citizens.

The primary actor regarding the NTRIS 2017–2021 policy is the Irish Department of Justice and Equality. Other actors include numerous government departments and state institutions, Irish society, Travellers, Roma people, Traveller and Roma organisations and NGOs, with the European Union in a monitoring role; indeed, the policy was produced in light of a direct mandate from the EU to protect Roma populations across Europe. The imbalance in power relations between actors is immediately obvious; government departments are better resourced and financed than NGOs, several of which are small, local groups. The government established a steering group—a cross-departmental initiative chaired by the Minister of State and composed of participants from fifteen government departments and eleven Traveller and Roma NGOs.

The government took all executive roles; therefore, the government fully controlled the policy-making process from start to finish. The policy demonstrates a top-down initiative by government departments, despite the Minister’s declaration on page 3 that, “We need to work together in a true partnership where Travellers and Roma groups and individuals work with Government [...] a collaborative and participative approach [...] so that Travellers and Roma will feel valued and empowered [...] (and) feel that they have ownership over, or input into, the decisions which affect their lives”. The optimistic, synergistic tone that imparts the message of “partnership” and “empowerment” is not carried over into the subsequent policy, as the analysis reveals that this is not an empowerment initiative. Empowerment is a process that starts with those who are oppressed and feel powerless, as they slowly develop self-esteem and gain control over their own lives; that is why the oppressed must be allowed to define the goals for an empowerment initiative.

The social construct of Travellers’ identity is maintained throughout the policy; thus, their societal status remains unchanged. The hegemonic established order maintains dominance through unequal power relations, keeping the dominant discourse unchallenged. This dominant discourse of institutions, expressed through systems of networks, as described by Foucault, infuses policy with an expert ideology (Foucault, 1991) to suppress empowerment and thus maintain the hegemony of the established order. Fine Gael, the centre-right ruling party, demonstrates its conservative ethos by the promotion of individual responsibility. This is associated with the neo-liberal ideology of “blame the victim”, which has been established in industrialised countries. As the analysis demonstrated, early on page 11 of the policy, the poor health choices and outcomes of Travellers are connected to their lack of personal responsibility. “Travellers’ access to health services ‘is at least as good as’ that of the general population, but Travellers are less likely to attend outpatient appointments or engage with preventative services”. This sentence is set up to convey the impression of a deficiency in personal qualities, since the opportunities afforded to Travellers are as good, or better than, everybody else’s—but they do not look after their own health. This aligns with the ideology of “blaming the victim” by ignoring the social, cultural and economic context in which the decisions take place.

The signs reinforce the established historical and social context via semiotic elements that remain normative and unchanging. By alienating the communities that the policy is meant to serve, the signs conveyed by these images are constructed to align with the dominant values. The semiotic content is scarcely linked to reality for any of the target populations, so the overall effect is somewhat dehumanising, downplaying the human rights of Travellers. By presenting a traditional view of Ireland, the semiotics function to preserve the established order and resist change. The policy signals a reproduction of the established order. This suggests that the NTRIS 2017–2021 policy is a manifestation of the wider hegemonic social practice and that the policy works to maintain the traditional, dominant discourse order within the political institution.

We can conclude that the policy does not help Travellers take control over their own lives. The government has not facilitated empowerment of the Travelling community to practice self-determination. The concept of discourse is often centred around theories of ideology, inequality and power. The discursive practice in the NTRIS 2017–2021 policy reveals unequal power relations between state actors and the Travelling community. As Foucault points out, the discourse of the institutions serves to produce and sustain unequal power relations between social groups. In this social context, the state tries to subjugate sections of society in order to dominate the discourse and maintain its hegemony.

5. Discussion

CDA is a research approach that examines communication in social and political contexts. Its primary focus is to analyse how discourses are formulated, maintained and challenged. Its function is to expose social power abuse, dominance and inequality [

19]. This study examined how networks of power are established and perpetuated in relation to the government through the key functions served by discourses in the formation of negative stereotypes about Travellers in Ireland. Discourse is not an objective truth. Through discourses, our interactions and use of language create our knowledge and shape our worldview.

Within Irish society, the dominant discourse has assigned an identity to the Traveller community as a homogenous group outside mainstream society. As the outsider group, the reality for Irish Travellers is that they have very little influence on the way in which their identity is constructed. In keeping with the social constructionist view that “reality” is a social construct, the state representations of the “image” of Travellers frequently assume the status of some form of objective “truth” regarding Travellers. All forms of human interaction contribute to, and influence, our worldview. When knowledge is disseminated by State institutions, we accept this as true. This is observed through Foucault’s concept of power, in that the government subtly exerts its power through systems of networks that aim to legitimise power imbalances and inequality in society [

24]. This is supported by the dominant discourse that is maintained by a government that acts from a position of privilege, enabling it to control the narrative.

The discourse is aligned with the majority view; this is evident in the relationship between the author and the reader. The authors, that is, the civil service and the minister, assure readers that the implementation of the policy will have minimal impact, as it has “no new legislative implications, creates no new rights and has no implications for public expenditure” [

13] (p. 7). Rather than serving the minority group for which the policy was created, the author tries to appeal to the majority, the general population. This is further evident in the stylistic presentation, promotional discourse and self-congratulation, as the Foreword declares, “This was a momentous and unprecedented decision in our country’s history” [

13] (p. 7). The state implies its power here by adopting an expert voice, from “privileged access to discourse and communication” [

25] (p. 233). The expert voice is a platform for disseminating expert knowledge, and through the formation of the discourse, this becomes the accepted knowledge, the “common sense”.

Society serves its own interest, so if the majority are not affected by the construct of that knowledge, the majority will go along with it and the discourse becomes normalised, leaving Travellers continuously excluded with no way of changing the construct of their identity. However, this does not reflect reality; it is constructed to retain power. In his concept of knowledge and power, Foucault claims that power is not only held by institutions; it is all around us in our daily lives, so power is accessible to the majority. By knowing what we know, we have the power to change the narrative on Travellers and move toward a fairer representation.

According to Foucault, aspects of power formation are intrinsically linked to ideology and are set up or maintained through discourses [

24,

26,

27]. Blaming Travellers for their own disadvantage aligns with the Fine Gael party’s economic liberalist ideology, promoted through the discursive practice in the policy, that makes an association between Travellers’ health outcomes and their lack of personal responsibility: “Travellers access to health services ‘is at least as good’ […] but Travellers are less likely to […] engage with preventative services” [

13] (p. 11). This is associated with the neo-liberal ideology of “blame the victim” that has been established in industrialised countries, an ideology that ignores the social, cultural and economic context in which the decisions take place [

28]. Through discursive practice, the assigned Traveller identity of “the most disadvantaged and marginalised people” [

13] (p. 2) predetermines and fixes their position in society, reinforcing the established order.

The findings on the NTRIS policy reveal the aspects of power formation by which the government shaped the policy. The government defined the goals, and even though there was a much-touted consultation with a steering group, policy making was controlled by the government from start to finish. Empowerment ideology is not evident since members of the oppressed group, as experts of their own lifeworld, were not given scope to define the goals [

22,

23].

The range of actors involved ensured a power imbalance, as the systems of networks were the main powerholders. This was shown in the text structure of the policy: in the discursive representations of Travellers and the visual semiotics of what we expect to be a “people-centred” policy, we see no people, no faces and no personal stories to put a human face on the document and make it relatable. This “absence of the human face” creates a very impersonal tone. The government had an opportunity to foster engagement at the societal level, but here, we see no connection with the communities the policy is meant to serve. The minister’s foreword asserts the political authority of the government, performing two discursive functions: first, signalling the importance of the document, and second, offering the Fine Gael-led coalition government the space to draw together a stylistic policy presentation that advances its neo-liberal agenda of individual choice, under the cover of irreconcilable concepts such as fairness and responsibility. The discursive practice reinforces the state’s position that Travellers experience a poorer quality of life because they are reluctant to engage with state services in the same way as the “settled population” [

13] (p. 14).

The findings of this CDA illustrate the point that discourses are more than just words; they have real consequences for Travellers in terms of life outcomes. Negative discourses contribute to unequal power relations in society. Here, the discursive practice of government within the social context is, through intertextual links, a repackaging of previous policy milestones, all of which have maintained the Traveller community outside the societal structure. Foucault tells us we can only analyse what is being said in a discourse formation at a particular point in time. We conducted an analysis of the NTRIS policy to detect signs of change in discourse formation that could indicate a change in the social construction of traveller identity. We examined the text, tracing a common thread that is intertextually linked to previous policy milestones, and we found no change in the discourse formation of Traveller identity. Shamefully, the government has used its privileged access to discourse and communication to prolong the exclusion of Travellers. This policy, therefore, will continue to produce poor outcomes for Travellers, while its ideology will blame Travellers for their disadvantages. If the country wants real change in Traveller outcomes, it must start with allowing the community to define the goals with a “bottom-up” approach that facilitates empowerment [

22]. The empowerment of the groups themselves is the foundation necessary to produce an equitable policy for minority groups. This is facilitated by increased Traveller participation in positions of power. To correct the power imbalances at the heart of the misplaced Traveller identity, Irish society must change to include all citizens equally. Within the social context, citizens must utilise the political process so that it works for society instead of for the self-preservation of hegemonic power.