Enacting Critical Citizenship: An Intersectional Approach to Global Citizenship Education

Abstract

1. Introduction

“I began by saying that one of the paradoxes of education was that precisely at the point when you begin to develop a conscience, you must find yourself at war with your society. It is your responsibility to change society if you think of yourself as an educated person.”James Baldwin [1]

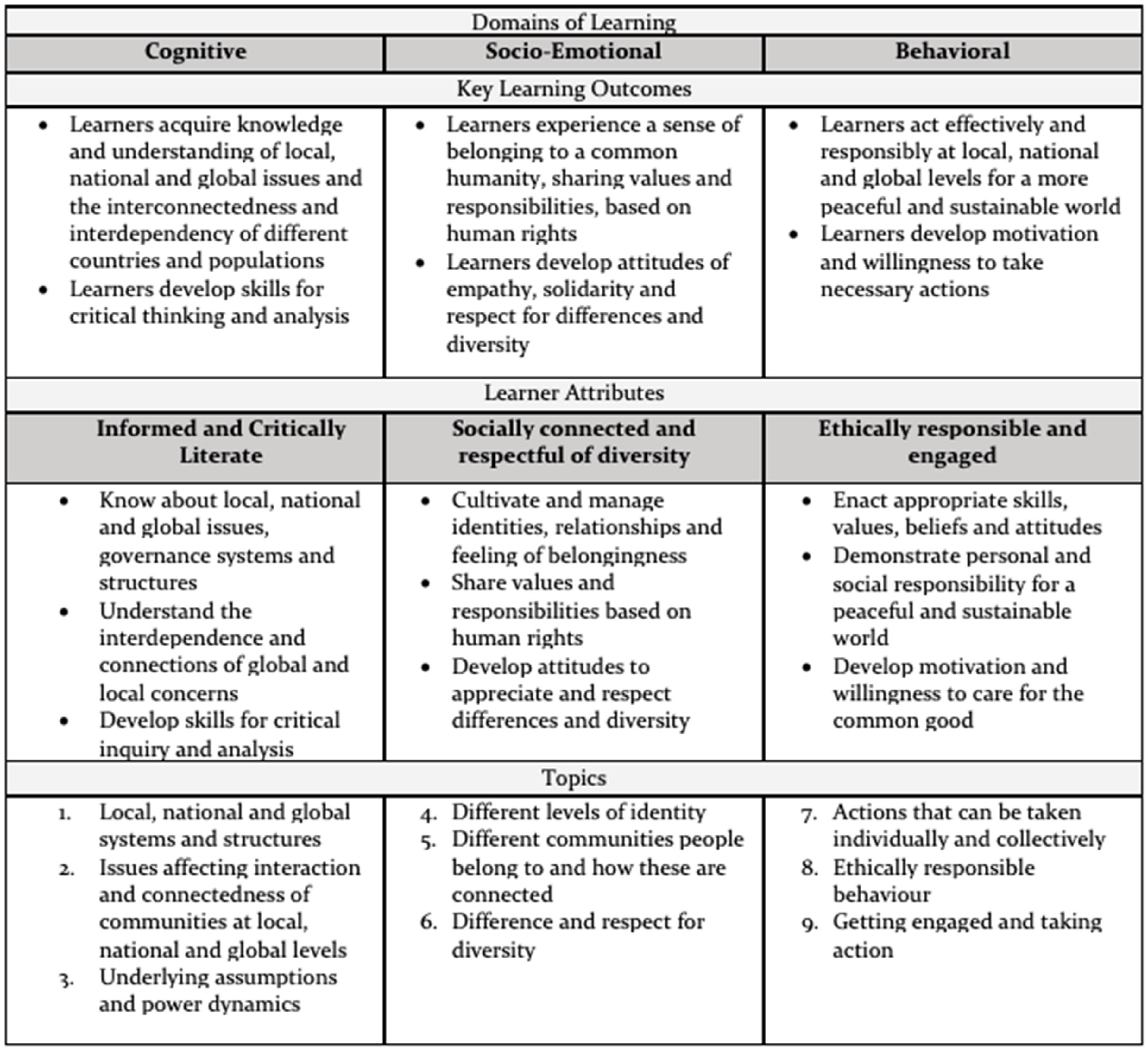

2. Global Citizenship Education

3. Towards a Critical Interpretation of Global Citizenship Education

“Empower students and help them acquire political efficacy [italics as in original], the school must help them become reflective social critics and skilled participants in social change. […] A major goal of the social action approach is to help students acquire the knowledge, values, and skills they need to participate in social change so that marginalized and excluded racial, ethnic, and cultural groups can become full participants in US society and the national will move closer to attaining its democratic ideal”.(p. 245)

4. A Brief History of Intersectionality

“From the onset of my involvement with the women’s movement I was disturbed by the white women’s liberationists insistence that race and sex where two separate issues. My life experience has shown me that the two issues are inseparable, that at the moment of my birth, two factors determined my destiny, my having been born black and my having been born female”.([23], p. 12)

“Women does not feel safe when her own culture, and white culture, are critical of her; when the male of all races hunt her as prey.Alienated from her mother culture, ‘alien’ in the dominant culture, the woman of color does not feel safe within the inner life of her Self”.(p. 20)

5. Doing Intersectionality

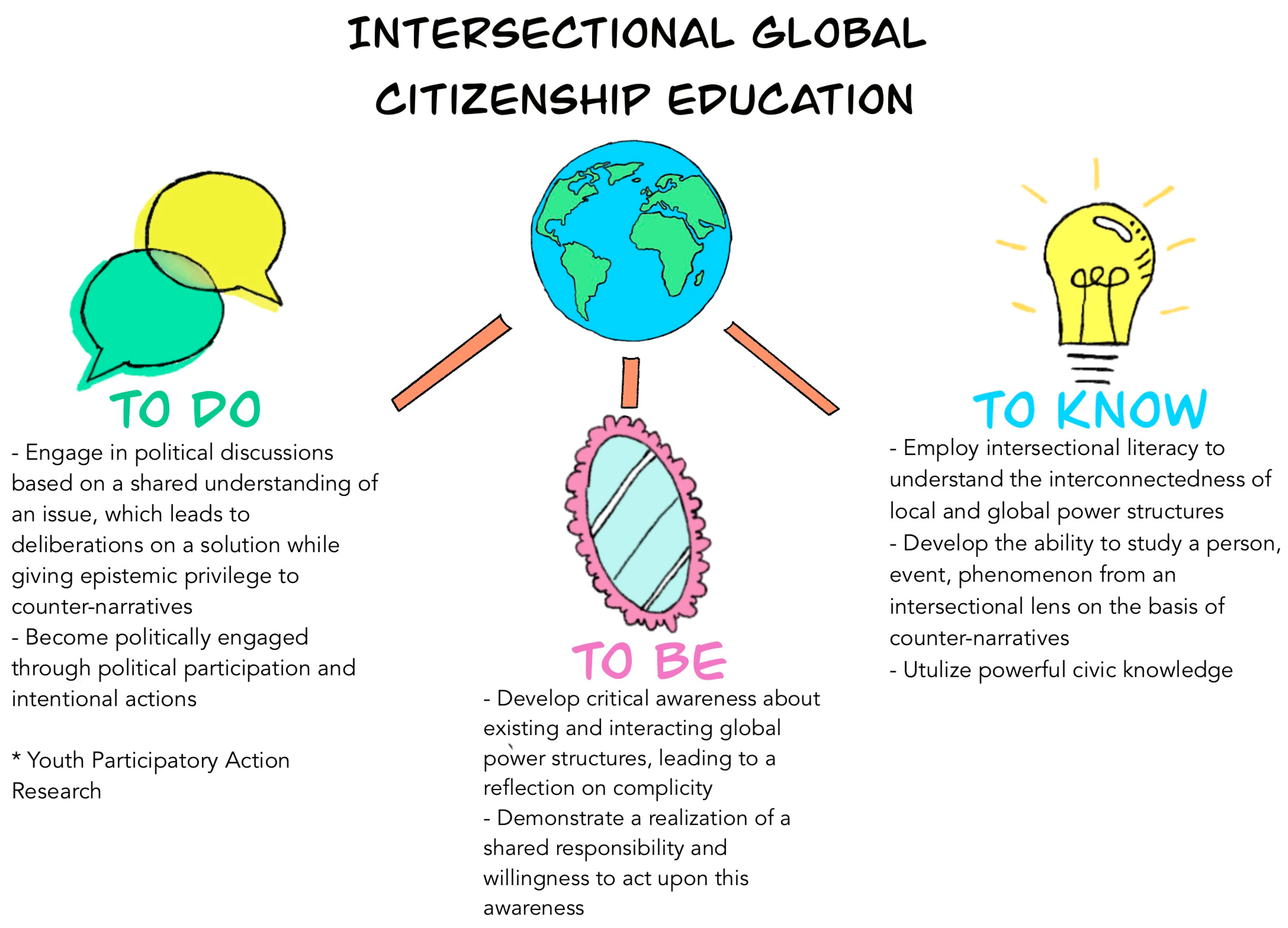

6. Nimbly Proposing Intersectional Global Citizenship Education

6.1. The Importance of Culturally Relevant Education for Any Critical Pedagogy

6.2. To Know

“I would ask them to consider whether there is any “special” knowledge to be acquired by hearing oppressed individuals speak from their experience—whether it be of victimization or resistance—that might make one want to create a privileged space for such discussion. Then we might explore ways individuals acquire knowledge about an experience they have not lived, asking ourselves what moral questions are raised when they speak for or about a reality that they do not know experientially, especially if they are speaking about an oppressed group.”(p. 89)

6.3. To Be

6.4. To Do

7. Postcritical Global Citizenship Education

8. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Baldwin, J. A talk to teachers. The Saturday Review. 21 December 1963. Available online: https://www.spps.org/cms/lib010/MN01910242/Centricity/Domain/125/baldwin_atalktoteachers_1_2.pdf (accessed on 3 July 2020).

- Tarozzi, M.; Torres, C. Global Citizenship Education and the Crises of Multiculturalism. Comparative Perspectives; Bloomsbury Academic: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Tarozzi, M.; Inguaggiato, C. Teachers’ Education in GCE: Emerging Issues in a Comparative Perspective; Springer Science and Business Media LLC.: Berlin, Germany, 2018; 164p. [Google Scholar]

- Andreotti, V. Soft versus critical global citizenship education. In Development Education in Policy and Practice; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2006; pp. 40–51. [Google Scholar]

- Pashby, K.; Sund, L. Decolonial options and foreclosures for global citizenship education and education for sustainable development. Nord. J. Comp. Int. Educ. 2020, 4, 66–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyson, C.A.; Park, S.C. Civic education, social justice and critical race theory. In The SAGE Handbook of Education for Citizenship and Democracy; Arthur, J., Davies, I., Hanh, C., Eds.; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2008; pp. 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, L.A. Theoretical foundations for social justice education. In Teaching for Diversity and Social Justice, 3rd ed.; Adams, M., Bell., L.A., Goodman, D.J., Joshi, K., Eds.; Taylor & Francis Group, Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 23–54. [Google Scholar]

- Kiwan, D. ‘Race’, ‘Ethnicity’ and Citizenship in education: Locating intersectionality and migration for social justice. In The Palgrave International Handbook of Education for Citizenship and Social Justice; Peterson, A., Hattam, R., Zembylas, M., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan UK: London, UK, 2016; pp. 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pashby, K.; da Costa, M.; Stein, S.; Andreotti, V. A meta-review of typologies of global citizenship education. Comp. Educ. 2020, 56, 144–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, C.A.; Stephen, D.H. Introduction. White women’s work? Unpacking its meaning and significance for the contemporary schooling of diverse youth. In White Women’s Work. Examining the Intersectionality of Teaching, Identity, and Race; Stephen, D.H., Chezare, A., Eds.; Information Age Publishing, Inc.: Charlotte, NC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bourn, D. The emergence of global education as a distinctive pedagogical field. In The Bloomsbury Handbook of Global Education, 1st ed.; Douglas, B., Ed.; Bloomsbury Handbooks; Bloomsbury Academic: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ramalho, T. Paulo freire: Accidental global citizen, global educator. In The Bloomsbury Handbook of Global Education, 1st ed.; Douglas, B., Ed.; Bloomsbury Academic: London, UK, 2020; pp. 52–60. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Global Citizenship Education. Topics and Learning Objectives. UNESCO, 2015. Available online: http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0023/002329/232993e.pdf (accessed on 12 June 2020).

- Zembylas, M. Affect, race, and white discomfort in schooling: Decolonial strategies for ‘pedagogies of discomfort’. Ethics Educ. 2018, 13, 86–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, S. Pluralizing possibilities for global learning in western higher education. In The Bloomsbury Handbook of Global Education, 1st ed.; Douglas, B., Ed.; Bloomsbury Academic: London, UK, 2020; pp. 63–75. [Google Scholar]

- Tuck, E.; Wayne, Y. Decolonization is not a metaphor. Decolonization Indig. Educ. Soc. 2012, 1, 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- Zembylas, M. Re-conceptualizing complicity in the social justice classroom: Affect, politics and anti-complicity pedagogy. Pedagog. Cult. Soc. 2020, 28, 317–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, J.A. Approaches to multicultural curriculum reform. In Multicultural Education. Issues and Perspectives, 7th ed.; James, A., Cherry, A., Banks, M., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA; pp. 233–256.

- Nash, J.C. Re-thinking intersectionality. Fem. Rev. 2008, 89, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.; Kimberlé, W.C.; Leslie, M. Toward a field of intersectionality studies: Theory, applications, and praxis. Signs J. Women Cult. Soc. 2013, 38, 785–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradi, B.; Patrick, R.G. Using intersectionality responsibly: Toward critical epistemology, structural analysis, and social justice activism. J. Couns. Psychol. 2017, 64, 500–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, P.H.; Sirma, B. Intersectionality; Key Concepts; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hooks, B. Ain’t I a Women. Black Women and Feminism; South End Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Anzaldúa, G. Borderlands. la Frontera. the New Mestiza; Aunt Lute Book Company: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1987; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw, K. Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanf. Law Rev. 1989, 43, 1241–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, C.P. Black Feminist Thought. Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, P.H. The difference that power makes: Intersectionality and participatory democracy. Investig. Fem. 2017, 8, 19–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memmi, A. Racism; Steve, M., Ed.; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2000; Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5749/j.ctt5vkbgd (accessed on 28 August 2020).

- Brah, A.; Ann, P. Ain’t I a woman? Revisiting intersectionality. J. Int. Women’s Stud. 2004, 5, 75–86. [Google Scholar]

- McCall, L. The complexity of intersectionality. Signs J. Women Cult. Soc. 2005, 30, 1771–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilge, S. Intersectionality undone: Saving intersectionality from feminist intersectionality studies. Du Bois Rev. Soc. Sci. Res. Race 2013, 10, 405–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, V.M. Contemporary sociological perspectives. In Pursuing Intersectionality, Unsettling Dominant Imaginaries; Taylor & Francis Group, Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ladson-Billings, G. But that’s just good teaching! The case for culturally relevant pedagogy. Theory Pract. 1995, 34, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krutka, D.; Milton, M. Taking Action in Social Studies Inquiries with Carly Muetterties. Visions of Education. 2019. Available online: https://visionsofed.com/2019/03/05/episode-107-taking-action-in-social-studies-inquiries-with-carly-muetterties/ (accessed on 23 July 2020).

- Ross, E.W. Rethinking Social Stucies. Critical Pedagogy in Pursuit of Dangerous Citizenship; Critical Constructions: Studies on Education and Society; Information Age Publishing, Inc.: Charlotte, NC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Freire, P. Pedagogy of the Oppressed, 30th ed.; Continuum: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Kamau, B.W.; Hari, K. Speaking with Bell Hooks & Talking DACA. Politically Re-Active. Available online: https://www.topic.com/politically-re-active (accessed on 5 July 2020).

- Ladson-Billings, G. Lies my teacher still tells. In Critical Race Theory Perspectives on the Social Studies: The Profession, Policies, and Curriculum; Information Age Publishing, Inc.: Charlotte, NC, USA, 2003; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Villegas, A.M.; Tamara, L. Preparing culturally responsive teachers: Rethinking the curriculum. J. Teach. Educ. 2012, 53, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, L.-C.; Paula, M.; Diana, H.; Brian, G. Teaching and learning about controversial issues and topics in the social studies. In The Wiley Handbook of Social Studies Research; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 319–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooks, B. Teaching Community. A Pedagogy of Hope; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Gay, G. Culturally Responsive Teaching. Theory, Research, and Practice, 3rd ed.; Multicultural Education Series; Teachers College Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Blackmore, C. The Opportunities and Challenges for a Critical Global Citizenship Education in One English Secondary School. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Bath, Bath, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wrigley, T. ‘Knowledge’, curriculum and social justice. Curric. J. 2018, 29, 4–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooks, B. Teaching to Transgress. Education as the Practice of Freedom; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Adami, R. The critical potential of using counternarratives in human rights education. In Critical Human Rights, Citizenship, and Democracy Education: Entanglements and Regenerations; Michalinos, Z., André, K., Eds.; Bloomsbury Collections; Bloomsbury Academic: London, UK, 2018; pp. 67–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elenes, C.A. Nepantla, spiritual activism, new tribalism: Chicana feminist transformative pedagogies and social justice education. J. Lat. Lat. Am. Stud. 2013, 5, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, J.A. Failed Citizenship and Transformative Civic Education. Educ. Res. 2017, 46, 366–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, D.R. New tribalism and chicana/o indigeneity in the work of gloria anzaldúa. In Routledge Handbook of Chicana/o Studies; Lomelí, F., Segura, D., Benjamin-Labarthe, E., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2019; pp. 242–255. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, E.W. Transformative learning theory. New Dir. Adult Contin. Educ. 2008, 2008, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, C.A. 13. transformative social justice learning: The legacy of paulo freire. In Utopian Pedagogy; Mark, C., Ed.; University of Toronto Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2007; pp. 242–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zembylas, M. Reinventing critical pedagogy as decolonizing pedagogy: The education of empathy. Rev. Educ. Pedagog. Cult. Stud. 2018, 40, 404–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menakem, R. My Grandmother’s Hands. Racialized Trauma and the Pathyway to Mending Our Hearts and Bodies; Central Recovery Press: Las Vegas, NV, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Pedwell, C. De-colonising empathy: Thinking affect transnationally. Samyukta A J. Women Stud. 2016, 16, 27–49. [Google Scholar]

- Young, I.M. Responsibility and global justice: A social connection model. Soc. Philos. Policy 2006, 23, 102–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, D.E.; Paula, M. The Political Classroom; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Abdi, A.A.; Shultz, L.; Pillay, T. Decolonizing global citizenship. In Decolonizing Global Citizenship Education; Sense Publishers: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, T. There’s Nothing Virtuous about Finding Common Ground. Time Magazine. 25 October 2018. Available online: https://time.com/5434381/tayari-jones-moral-middle-myth/ (accessed on 13 August 2020).

- Gibson, M. From deliberation to counter-narration: Toward a critical pedagogy for democratic citizenship. Theory Res. Soc. Educ. 2020, 48, 431–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, S.; Andreotti, V. Postcolonial insights for engaging difference in educational approaches to social justice and citizenship. In The Palgrave International Handbook of Education for Citizenship and Social Justice; Andrew, P., Robert, H., Michalinos, Z., James, A., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan UK: London, UK, 2016; pp. 229–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geographies of selves—Reimagining identity nos/otras (us/other), las nepantleras, and the new tribalism. In Light in the Dark/Luz En Lo Oscuro, Rewriting Identity, Spirituality, Reality; AnaLouise, K., Ed.; Latin America Otherwise; Duke University Press: Durham, NC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | In this paper, social justice references to the interpretations by Tyson and Park [6] and Bell [7], who both heavily draw on the work by Iris Marion Young, as such social justice can be explained as the elimination of injustices in distribution of resources as well as in participation and inclusion in the processes of everyday life. Thus, a social justice-orientation on citizenship education acknowledges the reality of injustices by focusing on oppression and domination, hereby highlighting the ideological, historical, and institutional foundation of these power imbalances. |

| 2 | BBC. Europe and right-wing nationalism: A country-by-country guide. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-36130006 (accessed on 11 August 2020). |

| 3 | For example, the treatment of Roma people in Hungarian government of prime-minister Viktor Orban and the attack on women’s rights in Poland under the administration of President Andrzej Dunda. |

| 4 | An example is a debate organized in the Netherlands by the Dutch Public Broadcasting (NPO) in which different stakeholders were debating on live television the statement whether or not the current debate about racism created a polarization in society. Organizations from Black communities organized a parallel session, as they made the point that racism was not something to debate about but to deliberately converse on. Lilith magazine. Nederland, We moeten het hebben over Racisme. Available online: https://www.lilithmag.nl/blog/2020/7/10/nederland-we-moeten-het-hebben-over-racisme (accessed on 11 August 2020). |

| 5 | The Combahee River Collective named itself after a raid led by Harriet Tubman during the Civil War, through which 750 enslaved people were liberated in South Carolina. Taylor, K. Until Black Women are Free None of Us Will be Free. The New Yorker. 2020. Available online: https://www.newyorker.com/news/our-columnists/until-black-women-are-free-none-of-us-will-be-free (accessed on 13 August 2020). |

| 6 | The title of the book “Ain’t I a Woman?” refers to a speech given by Sojourner Truth during a Women’s Rights Convention in 1851. This speech is considered one of the earliest publications of intersectional work, as the speech addresses the power imbalance between Black and white women in the women’s rights movement. The Sojourner Truth Project. Available online: https://www.thesojournertruthproject.com/. (accessed on 13 August 2020). |

| 7 | There are a number of terms, Culturally Responsive Teaching or Culturally Relevant Pedagogy, used to describe an educational approach that embraces students’ cultural and linguistic heritage and encourages teachers to utilize these in their teaching, in order to move away from deficit thinking about students from non-dominant cultures. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

de Vries, M. Enacting Critical Citizenship: An Intersectional Approach to Global Citizenship Education. Societies 2020, 10, 91. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc10040091

de Vries M. Enacting Critical Citizenship: An Intersectional Approach to Global Citizenship Education. Societies. 2020; 10(4):91. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc10040091

Chicago/Turabian Stylede Vries, Maayke. 2020. "Enacting Critical Citizenship: An Intersectional Approach to Global Citizenship Education" Societies 10, no. 4: 91. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc10040091

APA Stylede Vries, M. (2020). Enacting Critical Citizenship: An Intersectional Approach to Global Citizenship Education. Societies, 10(4), 91. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc10040091