1. Introduction

International migration has grown rapidly over the past fifteen years [

1]. As of 2017, the number of international migrants rose to 258 million with North America, Western Europe, Australia, and Arab states of the Persian Gulf as top destinations [

1]. Most international migrants settle in high-income nations and contribute to the language diversity of their destination countries [

1]. The United Stated (US) hosts a fifth of the world’s international migrants, who hail from different countries across the globe [

1]. As a result, over 300 languages are spoken in the US [

2], and nearly 25 million US residents are “limited English proficient” (LEP) i.e., they primarily communicate using their native language and have difficulty communicating in written or spoken English [

3].

For US-based immigrants, limited proficiency in English hinders access to healthcare services, which are typically delivered by monolingual, Anglophone providers [

4]. It must be noted that the ensuing language barriers should not be attributed to any perceived shortcomings among immigrants, but rather to the discordance between immigrants’ preferred language and the primary language of service provision. Language barriers particularly affect mental health services. We present a preliminary exploration of communication challenges, use of communication best practices, and training needs among mental health providers and interpreters working with LEP patients in the US.

1.1. Language Barriers in Mental Healthcare

Clear and extensive communication between patient and provider is fundamental for mental health. In the field of mental health, identifying problems and planning interventions relies on patient history, self-reporting, and interpersonal communication more than observable symptoms, biomarkers, and pharmacological management [

5,

6]. In addition, effective communication is essential for developing trust and addressing perceived stigma, personal illness narratives, and cultural attitudes that affect patient acceptance of mental health diagnosis and treatment [

5]. According to a synthesis report published by the World Health Organization, language barriers constitute one of the most important factors constricting mental healthcare access for immigrants who lack proficiency in the host country language [

7]. For example, in the US, first generation immigrants are less likely to use mental health services than their US-born counterparts even when symptomatic or having a probable diagnosis [

8,

9,

10]. Being LEP significantly lowers odds of receiving needed mental health services in the US [

11].

Similar barriers also exist in other countries. In a study on outpatient mental health services in Hamburg, Germany, of 485 psychotherapists surveyed, only a handful (3–4.5%) spoke a language other than German, and 43% reported refusing treatment for immigrant patients due to language barriers [

12]. A qualitative study with general practitioners in high-immigrant neighborhoods around Copenhagen, Denmark found that physicians were reluctant to refer immigrant patients for specialized mental health treatments due to anticipated language barriers [

13]. Lack of access to outpatient mental health services could lead to mental health crises warranting emergency care. A population-based cohort study in Ontario, Canada found that immigrant youth were more likely than non-immigrants to seek emergency department services for a first mental health crisis without previous outpatient mental healthcare [

14]. Rates of emergency department visits for a first mental health contact were higher for recent immigrants and those who had immigrated as refugees. Rates were also higher for immigrants from Central America and Africa than from North America and Western Europe. These disparities in access to outpatient mental health services were attributed to language barriers, difficulties with health system navigation, and referral biases by healthcare providers [

14].

Therefore, providing appropriate language access is critical for reducing mental health disparities for immigrants who are not proficient in the country’s dominant language. The need for linguistically accessible mental healthcare is even more acute under the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic conditions. Trends from around the world indicate that the pandemic and its social and economic repercussions are contributing to increased stress and anxiety among people. Although all people are likely to be affected, immigrant communities of color are especially vulnerable to the mental health fallout from the pandemic [

15].

1.2. Role of Interpreters in Providing Mental Health Care across Languages

Complications due to language barriers prevail even after immigrants access mental health service systems. For example, one qualitative study examined mental health services for immigrants in 16 major European cities. Mental health practitioners interviewed for the study identified language discordance as a major barrier to symptomatic assessment, diagnostic evaluation, and trust-building with immigrant patients who sought services [

16]. In the absence of bilingual and bicultural mental health providers, professional interpreters (those with formal training) are considered the most important resource to overcome language barriers, more important than ad hoc interpreters (untrained volunteers such as friends and family members), multilingual brochures and resources, and bilingual staff members [

17,

18]. A systematic review on the quality of mental health services for LEP patients found that use of professional versus ad hoc interpreters facilitates disclosure of sensitive material and improves patient satisfaction [

5]. Mental health providers rate professional interpreting as being of better quality and more satisfactory than ad hoc interpreting [

17].

One study found interpreter-mediated psychotherapy encounters to be as effective as those that did not require interpreter assistance, despite more difficult psychosocial conditions for patients who needed interpreters [

19]. Another study found that cognitive behavior therapy treatment provided with the help of interpreters was not only feasible but also effective in improving mental health outcomes for non-English speaking refugees in the UK with post-traumatic stress disorder [

20]. There is also some evidence suggesting that professional interpreters are better than bilingual providers at withholding judgement when patient accounts are unclear [

21].

Overall, available evidence suggests that high-quality interpreting services can be helpful in making mental healthcare accessible for immigrants who lack proficiency in their host country’s language. Access to appropriate mental healthcare can facilitate immigrants’ integration into their host society and have a broader societal impact.

1.3. Communication Challenges and Communication Best Practices when Working with Interpreters in Mental Healthcare

Although high-quality interpreters can go a long way toward bridging language gaps in mental healthcare, interpreter-mediated clinical encounters are not without challenges. A systematic review of interpreter use in mental healthcare identified a variety of interpreting errors across 26 peer-reviewed articles originating from six countries [

5]. Common errors included the interpreter answering on behalf of the patient, interjecting with opinions, rephrasing comments in ways that altered the conceptual meaning of what was said, editing the patient’s or the provider’s statements, and summarizing comments instead of interpreting verbatim. The review found that these errors were more likely to be made by ad hoc interpreters, but also occurred in the presence of professional interpreters [

22]. When they occurred, interpreting errors compromised the clinician’s ability to conduct safety evaluations, assess symptom severity, and understand treatment acceptance by the patient [

5].

We also identified communication challenges in our prior research on interpreter-mediated counseling sessions involving LEP patients of refugee background in an urban setting in the Midwestern US [

23]. For instance, the clinician’s efforts at therapeutic nuance and rapport-building strategies, such as jokes and tonal inflections, tended to get lost in translation. The clinician’s use of jargon and axiomatic expressions also complicated the interpreting process. In addition, side conversations between the patient and interpreter hampered trust building and hindered the therapeutic relationship. Difficulties with conveying empathy to the patient and fostering a therapeutic alliance in the presence of an interpreter were also reported in a survey-based study of primary care mental health practitioners in Montreal, Canada [

17]. The same study also found lack of clarity among practitioners on the interpreter’s role in the clinical encounter, with some expecting interpreters to go beyond basic translation and serve as cultural mediators and patient advocates [

17].

Some of the communication challenges reported above can be mitigated by training interpreters and mental health practitioners to work together to better serve LEP patients. For instance, interpreters might benefit from targeted training in mental health assignments and from guiding protocols on when it is appropriate to stay within or step out of the interpreting role. Communication challenges can also be addressed through clinicians’ use of specific strategies such as briefing and debriefing. Briefing refers to the process of apprising interpreters of the content, process, goals, and expectations of an upcoming treatment session or evaluation so they are better prepared for their role. Debriefing refers to sharing feedback and observations after the sessions to get a sense of whether the communication dynamics worked or did not work and to plan for future sessions [

24,

25]. The literature identifies these as best practices when working with interpreters to serve LEP patients in mental health [

26,

27].

Collectively, the above literature highlights how interpreter-mediated mental health encounters can be prone to communication difficulties. However, there has been little research on the extent of communication difficulties experienced when mental health practitioners work with interpreters and the use of communication best practices. As a result, there is a dearth of evidence to guide clinical practice and policy [

5].

We present a preliminary exploratory study that sought to: (1) examine mental health providers’ experiences with using interpreting services in their practice setting, (2) identify communication challenges experienced by mental health providers and interpreters when working with LEP patients, (3) examine the association between provider characteristics (level of professional education, years of professional experience, prior training to enhance knowledge and skills) and providers’ endorsement and use of specific communication practices when working with LEP patients, and (4) assess training needs among mental health providers and interpreters.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Conceptual Framework and Hypotheses

Our conceptual framework is based on our prior research involving direct observation and video recording of counseling sessions with LEP patients [

23]. Within this framework (described in detail in [

23]), the provider, patient, and interpreter constitute a triadic relationship that must be negotiated within each clinical encounter. Each member of the trio must enact different roles and responsibilities throughout the encounter. Communication is enhanced when the provider and interpreter discuss and reflect upon expected roles and responsibilities before and after each encounter, henceforth referred to as pre-session briefings and post-session debriefings.

In our experience, these communication practices are not covered in detail in standard entry-level training programs for mental health professionals. Therefore, we hypothesized that providers with a higher professional education level, more years of experience, and prior training with LEP patients would be more likely to endorse and use these practices.

2.2. Sampling and Data Collection

Using a cross-sectional observational study design and snowball sampling methods, mental health providers and interpreters were invited to participate in an online survey. Snowball sampling was used to recruit providers and interpreters who met the following criteria: 18 years or older, proficient in English, at least three months professional experience with LEP patients. The first two authors of this paper are members of a state-wide mental health task force that includes representatives from multiple community-based organizations that offer mental health services to LEP individuals. Permission was obtained to disseminate the surveys to members of the task force through an email list.

Surveys were administered via an online format using Qualtrics software. A single reusable link was generated for the provider and interpreter versions of the survey and shared with task force members. Members were encouraged to share the link with professional contacts and their respective professional organizations. The links remained active for three months. During this time, three reminders were posted to the task force email list.

The online survey was prefaced with information about risks and benefits of participation. Respondents indicated their consent by clicking a button. To encourage survey completion, respondents were given the option of entering a lottery for a $50 gift card. Data collection procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Illinois at Chicago.

2.3. Survey Development

Separate surveys were developed for providers and interpreters. Survey items were initially developed by the first two authors with support from a graduate research assistant. Draft items were reviewed and revised as needed by a survey development expert. The surveys were then pre-tested using the cognitive interviewing technique [

28] with two providers and two interpreters, respectively, and were revised iteratively with each pre-test.

2.4. Variable Description

Demographic variables included age, gender, and education level. Age was measured in years as a continuous variable. Gender was measured categorically as male, female, and other or non-binary gender. Education level was also measured categorically with response categories ranging from primary/elementary school to doctoral education.

Professional training and experience were measured using multiple variables. Providers were asked to report their professional background (e.g., psychiatrist, psychologist, nurse practitioner, social worker), current practice setting (e.g., private practice, hospital outpatient clinic, refugee agency, community mental health center), and time in practice, which was measured continuously in years and months. Interpreters were also asked to report their current practice setting and whether they were certified in healthcare interpreting. They were also asked to report their healthcare interpreting experience in years and months, as well as how much of their past interpreting work had been with mental health services, measured categorically on a scale ranging from “none” to “all”. Questions related to language(s) of proficiency and expertise in interpreting format (in-person, online, phone) were also included.

Providers’ experiences with using interpreting services were examined using a series of questions. Providers were asked how often they interacted with LEP patients on a four-point scale ranging from never to weekly or more often. They were also asked to report how often their current practice setting used any type of professional interpreting service on a five-point scale ranging from “never” to “always”. If professional interpreters were used, respondents were asked to report the type of interpreting services (in-person, online, phone). If professional interpreters were not used, respondents were asked to specify why by selecting from a list of reasons such as patient’s English being adequate, presence of bilingual staff, etc. Providers were also asked about the extent to which they agreed that using a professional interpreter was necessary when working with LEP patients.

To identify communication challenges, a unique list of challenges was developed for each respondent group. These items were based on our prior research and a review of the literature on communication challenges in mental healthcare, which is reported in the previous section. Respondents were asked to report how often they experienced these challenges on a four-point scale ranging from “never” to “usually”. Cronbach’s alpha for the nine challenges presented in the provider survey was 0.78. Cronbach’s alpha for the twelve challenges presented in the interpreter survey was 0.71. Respondents also had the option of describing “other” challenges not included in the list. The provider survey included additional questions exploring prior experience with interpreting services.

Endorsement and use of best practices were assessed using two questions. First, both groups of respondents were asked to rate how often they participated in pre-session briefings and post-session debriefings on a five-point scale ranging from “never” to “always”. In addition, providers were asked to rate the importance of engaging in these recommended practices on a four-point scale ranging from “not at all” to “very important”. Cronbach’s alpha for the four items in the provider survey was 0.80 and for the two items in the interpreter survey was 0.65.

Both surveys included items that addressed respondents’ previous training in mental healthcare for LEP patients and their future training needs and interests. Providers were asked to report the number of hours of training they had received for working with LEP individuals and interpreters. Similarly, interpreters were asked to report hours of training received in general healthcare interpreting and, specifically, mental health interpreting. They were also asked to rate their perceived level of preparation for mental health interpreting on a four-point scale ranging from “extremely prepared” to “extremely unprepared”. In addition, both groups of respondents were asked whether they were interested in future training by indicating response options of yes/no/maybe. They were also asked to identify topics of interest for future trainings. Separate topic lists were generated based on our previous research and the extensive literature reported in the previous section. Respondents also had the option of writing on additional topics not mentioned in the pre-set list.

2.5. Data Analysis

Mean, median, and range were computed for continuous variables; frequencies and proportions were computed for categorical variables. For items that required respondents to indicate preferences (e.g., topics for future training), response options were ranked in descending order by frequency. Chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests were used to test whether use and endorsement of best practices was associated with providers’ level of professional education and prior training. Association with years of professional experience was tested using the t-test or Wilcoxon rank-sum test for non-normal data. An alpha level of 0.05 was used to determine statistical significance. Because this was a preliminary exploratory study with a small sample size, we did not correct for multiple tests.

Open-ended comments for “other” communication challenges experienced by respondents were reviewed and compiled by the first two authors. Sample verbatim comments are presented with the quantitative results where appropriate.

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

Complete surveys were obtained from 38 providers and 34 interpreters. Thirty-four providers reported demographic information. The majority identified as female (91%) with a mean age of 37.9 years (SD = 11.4, Median = 33.5, Range 24–59). Most (74%) had a master’s degree, followed by bachelor’s (16%), and doctoral (10%) education. Most providers were social workers (47%) or psychologists (26%). Other professions included counseling, occupational therapy, nursing, family medicine, dance and movement therapy, and research and evaluation. On average, providers had 6.6 years of professional experience (SD = 9.3, Median = 3 years, Range 3 months to 38 years). Most common practice settings included community mental health centers, refugee resettlement centers, and torture treatment centers, each representing 26–28% of the sample.

Of the 34 interpreters, twenty-two interpreted for French, while the remaining respondents were split between ten languages including Amharic, Arabic, Assyrian, Burmese, German, Nepali, Somali, Spanish, Swahili, and Tigrinya. Thirty-one interpreters provided demographic data. Of these, 74% identified as female with a mean age of 47.2 years (SD = 15.6, Median = 49, Range 22–69). Most had a bachelor’s (44%) or master’s (44%) degree; three had a doctoral degree, and one had a high school or GED education. On average, interpreters had 4.4 years of experience in healthcare interpreting (SD = 4.5, Median = 3.2 years, Range 3 months to 23 years). All but one had experience with in-person interpreting; fourteen had also done phone interpreting. Six interpreters reported that all of their past interpreting work had been in mental health services, nine reported most of their work had been in mental health, 16 reported that some or a small amount of their prior work had been in mental health, and three reported none of their prior work (barring their current work setting) had been in mental health. Most common work settings included torture treatment centers (77%), followed by refugee resettlement agencies (32%).

3.2. Providers’ Experiences with Using Interpreting Services

Twenty-nine providers (76%) saw LEP patients weekly or more often; seven providers (18%) saw LEP patients a few times a month, while two (5%) saw LEP patients only a few times a year. Over 35 patient languages were reported, the commonest being Arabic, Somali, Spanish, Swahili, French, Nepali, Burmese, and Amharic.

Most providers (97%) agreed or strongly agreed that using a professional interpreter was necessary when working with LEP patients. Six providers (16%) stated that professional interpreting services were always available when needed at their current workplace; 23 providers (61%) stated that interpreting was usually available; four providers (10%) stated that interpreting was sometimes available; and five (13%) stated it was rarely or never available. Professional interpreting, when available, was mostly in the form of in-person interpreting (63%). Unavailability of professional interpreters was one of the commonest reasons for not using interpreting even when needed (i.e., when the patient’s English was inadequate and in the absence of bilingual staff).

3.3. Communication Challenges

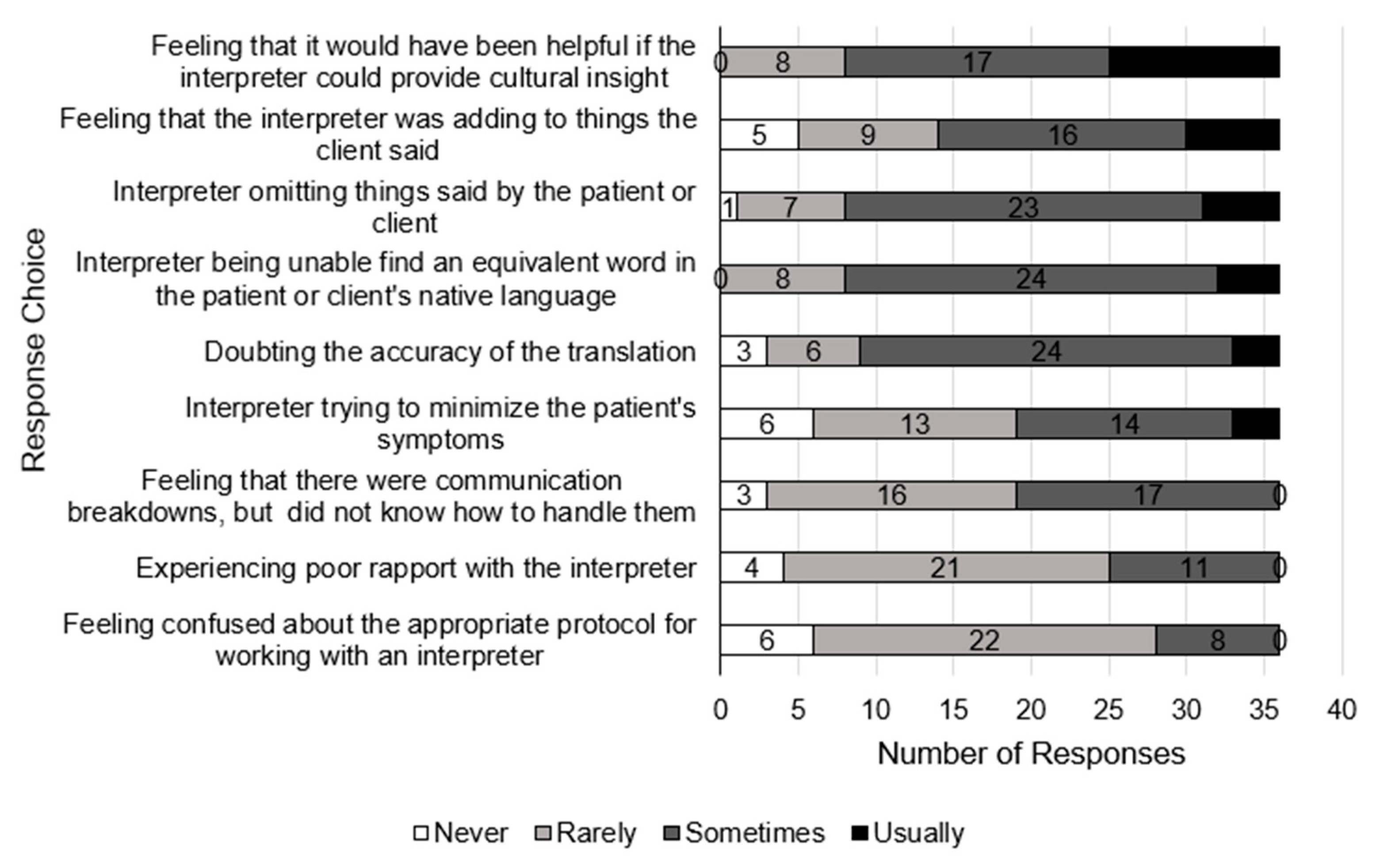

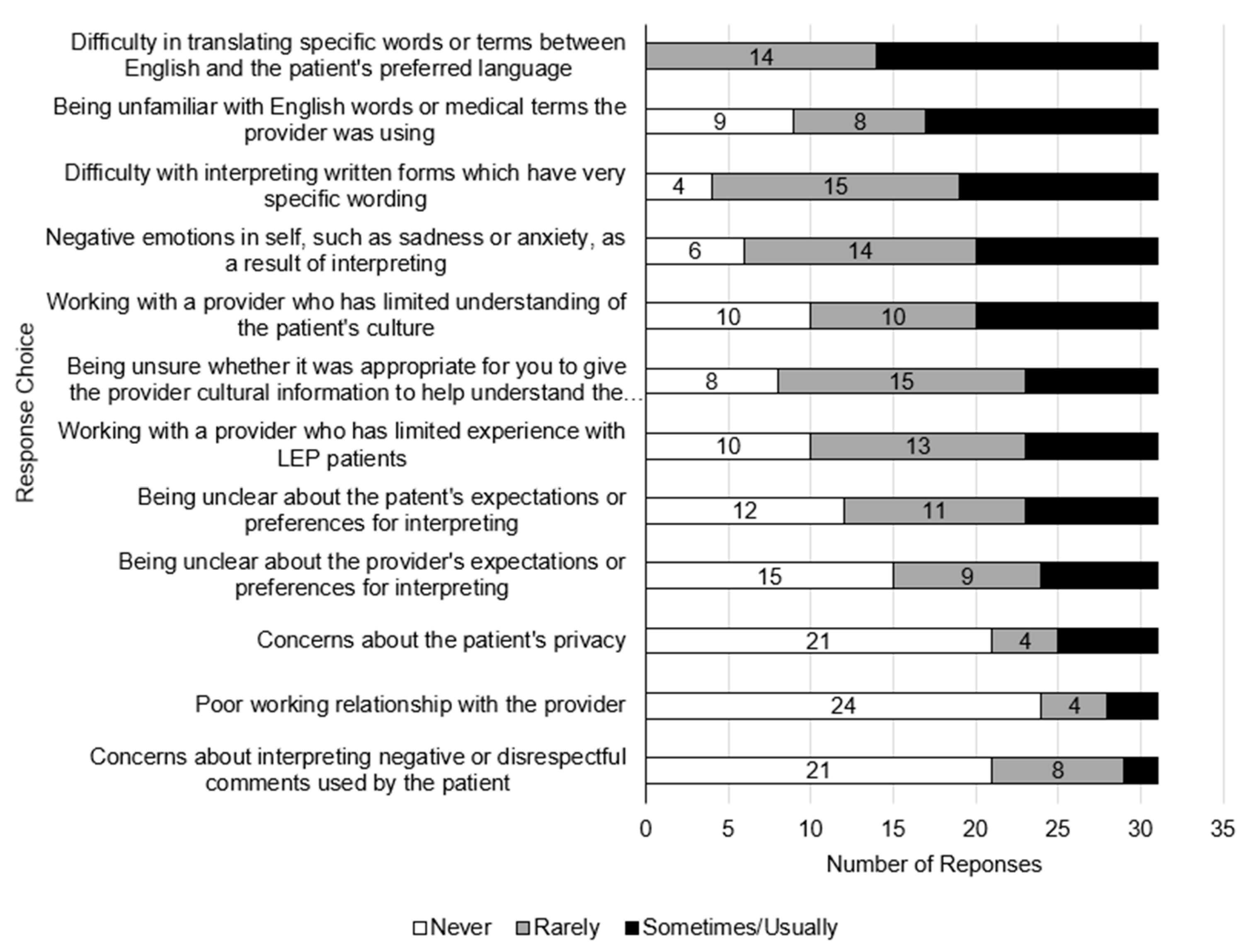

Thirty-six providers and 31 interpreters responded to questions about communication challenges (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2).

Some respondents reported distinct challenges in addition to ones listed on the survey. Two interpreters described ethical dilemmas about divulging patient information outside the clinical encounter:

“Also, as I sometimes converse w[ith] client while in the waiting area, I sometime have information that may be relevant to the provider, yet do not always know if I can share said info.”

Another challenge reported by two interpreters related to uncertainty about providing clarifications when interpreting:

“I sometimes feel the need to clarify the provider’s questions for the client and do not always know when that is appropriate.”

Finally, three interpreters reported difficulty with managing professional boundaries:

“Suppressing my own impulses to comfort client, knowing when it might be appropriate to do so…”

“Trying to maintain a psychological distance from the client whose stories are often very difficult to absorb. I always want to “save the world” and maintaining that distance is crucial to doing a good job, although never at the expense of empathy or compassion…”

Concerns about interpreters’ professional boundaries and related patient confidentiality and trust were also reported by nine providers. A sampling of their comments follows:

“… issues of trust take time to build and initially a client may not feel comfortable with an interpreter from their community even with reassurances about confidentiality.”

“Many times the interpreter does not fully understand the appropriate roles they are required to play during interpretation services…sometimes interpreters will take it upon themselves to offer advice to the clients that the provider has not given, which makes that relationship strained (and the client will potentially think the provider is offering that advice).”

“Interpreters becoming emotional during session as he/she over-identifies with the client’s story.”

Two providers specifically discussed issues with phone interpreting such as bad phone connections and phone interpreters being unable to see the patient’s body language and facial expressions. Two providers raised concerns about interpreters’ ability to understand and empathize with mental health problems.

3.4. Endorsement and Use of Best Practices

Thirty-six providers responded to questions about endorsement of best practices. Of these, 16 (44%) rated pre-session briefings with interpreters as very important, 13 (36%) as somewhat important, and seven (19%) as a little important. Fourteen providers (39%) rated post-session debriefings with interpreters as very important, 14 (39%) as somewhat important, and eight (22%) as a little important. Providers with master’s or doctoral level education were more likely to rate pre-session briefings as very important compared with those who had a bachelor’s degree (p = 0.02, two-tailed Fisher’s exact test). Those with master’s or doctoral degrees were also more likely to rate post-session debriefings as very important. This association was not statistically significant but approached significance (p = 0.06, two-tailed Fisher’s exact test). Years of professional experience and prior training with LEP patients and interpreters were not significantly associated with endorsement of these practices.

Thirty-six providers and 31 interpreters reported data on use of best practices. One provider and two interpreters reported always engaging in pre-session briefings. Eight providers (22%) and five interpreters (16%) usually engaged in pre-session briefings. Twelve providers (33%) and 12 interpreters (39%) engaged in pre-session briefings sometimes. Ten providers (28%) and eight interpreters (26%) rarely engaged in pre-session briefings. Five providers (14%) and four interpreters (13%) reported never engaging in pre-session briefings. Providers with master’s or doctoral level education engaged in pre-session briefings more frequently (sometimes/usually/always rather than rarely/never) compared with those who had a bachelor’s degree (p = 0.003, two-tailed Fisher’s exact test). Years of professional experience, and prior training were not significantly associated with use of pre-session briefings.

No provider and one interpreter stated that they always engaged in post-session debriefings. Seven providers (19%) and four interpreters (13%) usually engaged in post-session debriefings. Eleven providers (31%) and 12 interpreters (39%) engaged in post-session debriefings sometimes. Twelve providers (33%) and eight interpreters (26%) engaged in post-session debriefings rarely. Six providers (17%) and six interpreters (18%) reported never engaging in post-session debriefings.

Level of professional education and prior training were not significantly associated with use of post-session debriefings. The association with professional experience trended toward significance on both the t-test (t(34) = −2.2, p = 0.07) and Wilcoxon test (p = 0.09), such that providers who engaged in post-session debriefings usually or always had more years of professional experience (M = 17.0, SD = 15.2) than those who engaged in this practice sometimes, rarely, or never (M = 4.4, SD = 5.5).

3.5. Training History and Training Needs of Providers

Thirty-six providers responded to training-related questions. Of these, 15 (42%) had received prior training on working with LEP patients, with about half (n = 8) having received less than 10 h of training. Seventeen (47%) had received training on working with interpreters, with the majority (n = 11) having received less than 10 h of training.

Thirty-five providers responded to questions about future training needs. Of these, only three stated they would

not be interested in additional training. Nineteen responded with a “yes” and thirteen with a “maybe”.

Table 1 summarizes preferred topics for future training.

3.6. Training History and Training Needs of Interpreters

Of the 34 interpreters, five had certification for healthcare interpreting, and 11 (32%) had completed any formal training in general healthcare interpreting. Of these, most (n = 7) had received 10 h or more of training. Seven interpreters (21%) had participated in formal training specific to mental health interpreting. Of these, only one interpreter had received 10 h or more of mental health training.

Thirty-one interpreters responded to questions about future training needs. Of these, seven interpreters (23%) believed they were

extremely prepared for mental health interpreting; 23 interpreters (74%) felt they were

somewhat prepared; one interpreter reported being

somewhat unprepared for mental health interpreting. Twenty-six interpreters of the 31 who responded to this question (84%) were interested in additional training to enhance their skills for mental health interpreting.

Table 1 summarizes preferred topics for future training.

4. Discussion

Survey findings yielded several important insights. Most providers endorsed the use of professional interpreters when working with LEP patients. Yet, only a small fraction reported that professional interpreters were always available when needed at their current workplace. This finding is notable given that most provider respondents worked in settings which frequently served LEP patients. Previous literature has similarly reported the scarcity of qualified spoken and sign language interpreters trained to work in mental health [

29]. Ongoing scarcity of professional interpreters can seriously hinder access to needed mental health services and exacerbate healthcare disparities.

Even when working with interpreters, providers identified multiple communication challenges; the commonest being a need for greater cultural insight from the interpreter. That interpreters should provide socio-cultural information about the patient in addition to interpreting was a common expectation cited by mental health primary care practitioners in another study [

17]. Indeed, the field of healthcare interpreting is trending away from conceptualizing the role of interpreters as invisible transmitters of information. Increasingly, scholars and experts recommend an expanded role for interpreters as cultural informants [

30,

31]. However, if interpreters are to provide cultural mediation, they must be selected based on language

and cultural expertise. Not all bilingual interpreters have knowledge of specific cultural or contextual issues, a fact that is often overlooked in the standard practice of hiring interpreters based on language skills only. Furthermore, it is important that this expanded view of mental health interpreters’ role be translated into specific professional expectations and guidelines. Several interpreters who responded to our survey reported being unsure about when it was appropriate to provide cultural information.

A related challenge reported by interpreters was difficulty with negotiating professional boundaries and ethical dilemmas. Providers echoed a similar concern about interpreters’ blurred roles, especially when interpreters belonged to the patient’s cultural community. Previous qualitative research has shown that blurred role boundaries and conflicting expectations interfere with interpreter performance [

32]. Ethical dilemmas and role ambivalence experienced by interpreters have been attributed to lack of institutional recognition of their labor and contributions [

33]. Collectively, these findings suggest a need for better institutional support for interpreters in the form of supervision and practice guidelines that delineate mental health interpreter responsibilities and establish professional standards and boundaries for interpreting in mental health settings. Recommended guidelines could identify situations where it would be appropriate for an interpreter to provide cultural nuance and suggestions for offering cultural insights without conveying assumptions about the patient. There exists precedent for nationally recognized professional standards and guidelines for mental health interpreting in other countries. For example, in France, a working group of non-profit organizations, including organizations that focus on mental health interpreting, has developed a charter for professional interpreting standards at the behest of the national health authority [

34]. Practice guidelines for mental health interpreters have also been developed in Australia and are endorsed by national professional associations representing spoken and sign language interpreters [

35]. These documents can serve as a starting point for similar endeavors in other countries such as the United States.

Providers also reported concerns about interpreters embellishing or omitting patients’ comments. Many providers also doubted the accuracy of interpretation or felt interpreters tried to minimize patients’ symptoms. These concerns suggest that providers did not always trust that interpreters were executing their role appropriately. Previous literature indicates that trust between providers and interpreters is a key factor for effective communication, more so in mental health than in any other setting [

23,

34].

An effective strategy for building trust between providers and interpreters is through pre-session briefings and post-session debriefings. These practices can also avert other communication challenges. For example, pre-session briefings can familiarize interpreters with psychiatric jargon and standardized assessments to minimize technical difficulties, which constituted common challenges reported by interpreters in our study. Post-session briefings can address any secondary trauma experienced by interpreters, which was also reported by a substantial number of interpreters in our study. Other studies have also reported high rates of secondary trauma among mental health interpreters [

36]. In the absence of post-session debriefings, interpreters are left to their own resources to manage the emotional impact of trauma as they often lack formal training on coping mechanisms [

36].

Although pre-session briefings and post-session debriefings are highly recommended in the literature [

26,

27], both providers and interpreters reported infrequent use of these practices. We had hypothesized that endorsement and use of these practices would be higher among providers with higher levels of professional education, and greater professional experience. Providers with master’s or doctoral degrees were more likely to endorse these practices than those with bachelor’s degrees. Providers with master’s or doctoral degrees were also likely to engage in pre-session briefings more frequently, while those with more years of professional experience were likely to engage in post-session debriefings more frequently (trending toward significance). This finding suggests that providers learn to value and implement these practices through either advanced professional training or on-the-job experiences. Thus, it is imperative that these best practices be introduced in bachelor’s programs and/or in workplace orientations for entry-level providers. It is also important that employers create a workplace that is conducive to implementation of these practices by allowing adequate time for briefings and debriefings between appointments.

We also hypothesized that use of pre-session briefings and post-session debriefings would be higher among providers who had prior training for working with LEP patients and interpreters. However, providers’ use of pre-session briefings and post-session debriefings was not associated with prior training. One reason for this could be that majority of providers who reported prior training had only received a minimal amount of training (<10 h). It is likely that short duration trainings do not adequately address these best practices.

Relatedly, 54% of the providers in our study were interested in receiving additional training. Preferred training topics corresponded to common challenges identified by providers. For example, providers expected interpreters to elucidate cultural details during encounters with LEP patients. Accordingly, a top training topic addressed understanding sociocultural norms that affect communication. Providers also expressed concerns about interpreters’ role boundaries. A corresponding training topic coveted by providers was learning how to negotiate different interpreter roles and related communication dynamics.

Interest in further training was higher among interpreters. Only seven interpreters had received mental health training. Three quarters of interpreters felt somewhat prepared for mental health settings, and 84% were interested in additional training. Interpreters’ preferred training topics included learning mental health terminology and tackling technical issues. These preferred topics correspond to the technical communication challenges most frequently identified by interpreters. Dealing with emotionally difficult sessions was also a highly coveted topic, and one that relates to interpreters’ experiences of secondary trauma when interpreting. Exposing interpreters to common mental health conditions and related treatments can enhance their ability to facilitate therapeutic communication between the patient and provider, as well as enable interpreters to manage their own well-being and derive greater job satisfaction [

37]. Finally, interpreters wanted to learn when and how to provide cultural context during a session, as this was also a commonly reported challenge.

These findings reiterate that both mental health providers and interpreters could benefit from specialized training to enhance their professional skills, build successful working alliances, create opportunities for professional dialogue, and better serve patients who speak a different language [

38]. The above findings also inform the development of customized trainings, designed to fill skill deficits identified by providers and interpreters. Therefore, an important direction for future research relates to development, implementation, and evaluation of professional skill-building trainings for mental health providers and interpreters. The literature also recommends combined programs for training practitioners and interpreters to work as a team [

39]. Also needed is research that investigates how these trainings affect service access, quality of care, and mental health outcomes for immigrant and refugee patients who lack proficiency in the language of their host country.

Limitations

The study sample size precluded analytic strategies such as multiple regression analysis, which could have helped isolate the most significant predictors of utilization of best practices. We did not adjust the alpha level for multiple tests; therefore, it is important that our findings be replicated in studies with larger samples. We did not collect data on the geographical locations of respondents, and it is likely that our recruitment strategy generated a sample with little geographical variation. In addition, the majority of the respondents identified as female, and many worked in settings such as refugee resettlement agencies and torture treatment centers, which are likely to be interconnected and also serve large numbers of LEP patients. Therefore, their responses might be representative of only a small subset of mental health providers and interpreters. We also did not collect data on language difficulties from the perspective of patients. Some language difficulties experienced by patients might be conflated by their mental health diagnoses, an important consideration for future research. Finally, all variables were measured using survey items developed by study authors. While face validity of these items was assessed through pre-testing and cognitive interviews, more elaborate evaluations of content and construct validity were beyond the scope of this study.