Centering the Complexity of Long-Term Unemployment: Lessons Learned from a Critical Occupational Science Inquiry

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Theoretical Underpinnings

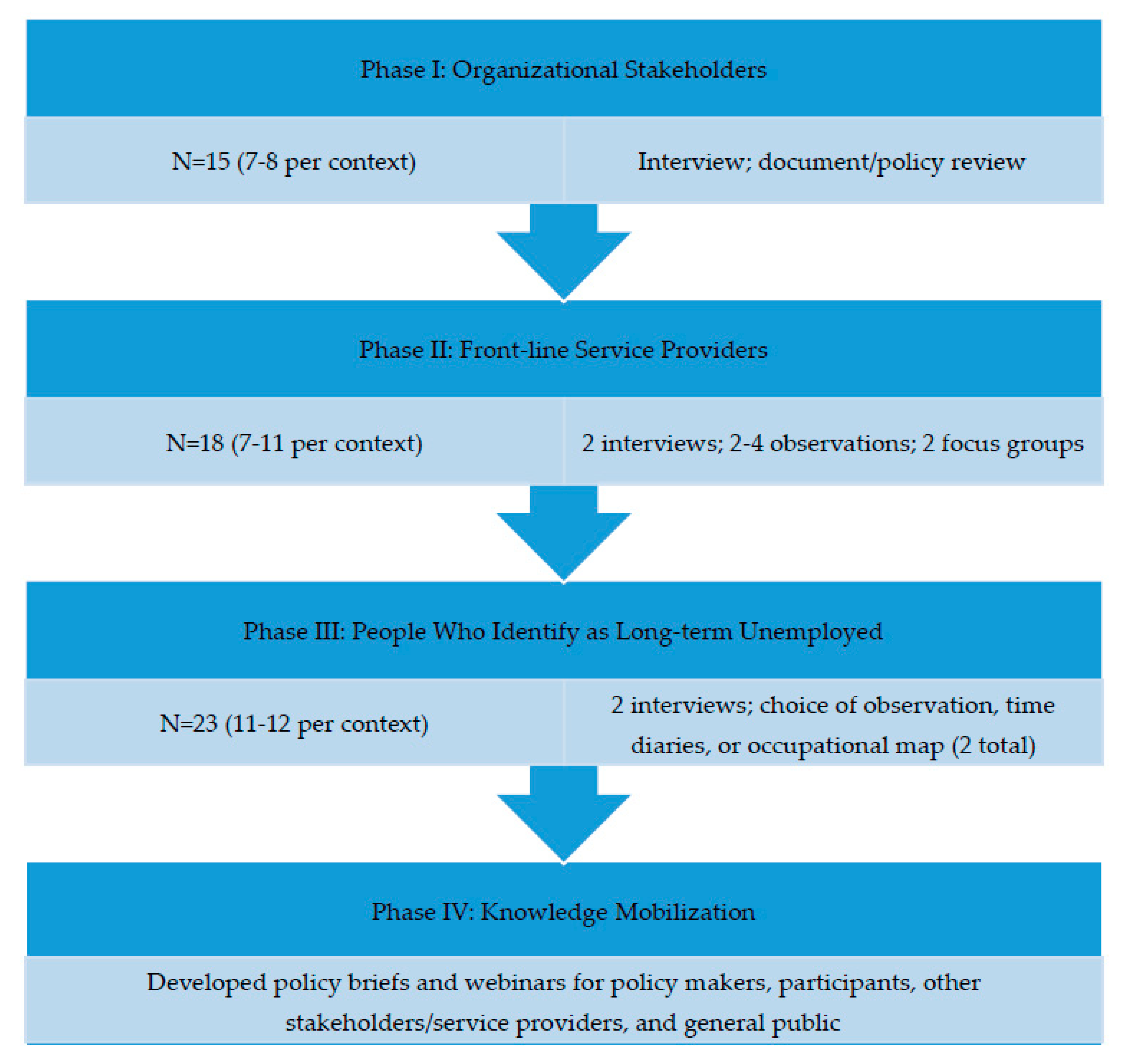

2.2. Study Design

2.3. Participant Recruitment and Demographics

2.4. Description of Methods

2.5. Analytic Approaches

2.6. Ethical Permissions

3. Findings

3.1. Aspects of Participant Definitions

3.1.1. Duration of Unemployment

I think that when we deal with the state on some of our programs, when they talk about long-term unemployment they talk about people who have exhausted their 26 weeks of eligibility of unemployment compensation which is now going down to 21 weeks or something... But I think that when we talk about long-term unemployed just around here, when you talk about it, not in the context of specific eligibility requirements of a specific program, I think we’re talking about folks that were never more than marginally attached to the labor force… So there’s sort of a technical definition, which we have to adhere to in many cases, and then there’s the longer.

3.1.2. Patterns of Labor Force Participation

3.1.3. Financial Precarity

I know what we say long-term unemployed is but to the job seeker it would be anytime you can’t pay your bills, when you start losing your home and your cars, can’t put food on your table, can’t pay your utility bills. So that could be anywhere from three weeks or six weeks for some people.

[Long-term unemployment] depends really upon the situation of the individual client, especially upon that client’s financial situation. For some people, missing one or two paychecks can be catastrophic. For others, they’re content to wait until ‘the ideal job’ comes along.

Long-term unemployment to me would be anything over a month. I look at it as anything that can put you in a position to where you’re possibly not going to be able to dig yourself out. You’re gonna have to go through some super hard times before you can get back to where you were. I would say a month, month and a half because that gives you enough time if you live paycheck to paycheck to kind of go, ‘Okay, well, now I haven’t been able to pay this bill.’

I would think being out of work with your resources becoming a concern, with your energy-I don’t know if that’s the right word-I’m just looking at my colleagues and some of them are getting discouraged and things like that. I’m not at that point.

I had saved a decent amount of money so we’re lucky enough to have that to fall back on, but again, as someone who saved a lot of money with the anticipation of using it for retirement, it’s not something I want to do.

3.1.4. Emotional Changes

Someone who’s struggling…like you get so discouraged that you’re just at a point where, why should I try, you know? Like it’s, why am I going to keep sending our resumes, for what, to waste paper? Like, I’m costing myself more money than anything. Like I’m at a point where I’m better off to sit at home on welfare now than to do anything which is sad.

People that fell out of the job market that has pretty much exhausted a lot of their resources, possibly people that have not redefined themselves or retooled themselves, or people that probably, I would say, just gave up on employment for a while, and probably hoping that the market gets better.

3.1.5. Up to the Individual

It depends on each individual client…Long-term is kind of up to the individual, but I think it depends on their background, and their values, and their experience–what they consider long-term, versus us. For me, it might be 6 months, but I’ve had several clients who have had years of unemployment.

The effects of long-term unemployment in terms of an economic or social status or in terms of just feeling like a person, they vary from individual to individual. So it’s hard to define. It’s hard to have an empirical answer or a static answer to that because it’s so fluid.

3.2. Definitional Variations and Service Provision

To me, the most confusing part of this is how to differentiate between long-term unemployed, as in those folks who were at some point in time had a strong attachment to the labor market and then lost that attachment, versus those people that never had it…the folks that lack any kind of economical opportunity…not all of those meet the eligibility definitions of the Department of Labor or some of the other funding agencies for that matter.

[We] have a very client-centric model whereby the individual is in the driver’s seat, and we’re coaches and facilitators in helping them to document and then initiate their plan. So how long-term unemployment is defined, I don’t think it [impacts] service delivery because every single person is a unique employment action plan depending on a myriad of factors.

A lot of service programs don’t advertise ‘This is for…long-term unemployed individuals.’ So if someone needs help with a job, they’re just going to that agency or being referred in. So I don’t think it makes that big of a difference in terms of the service delivery portion of it.

3.3. Understanding Definitions Vis-À-Vis the Intersecting Factors that Shape Everyday Life during Long-Term Unemployment

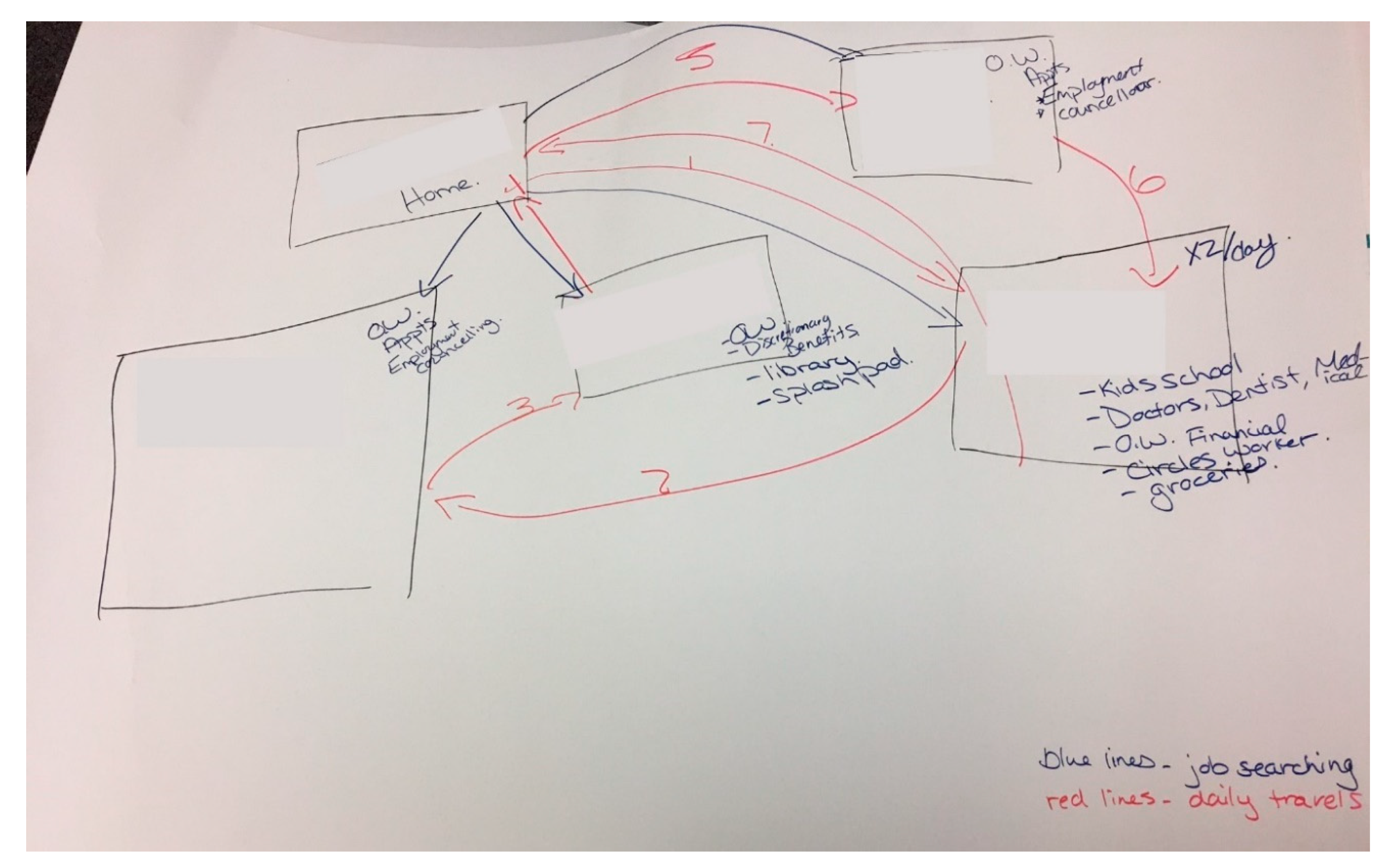

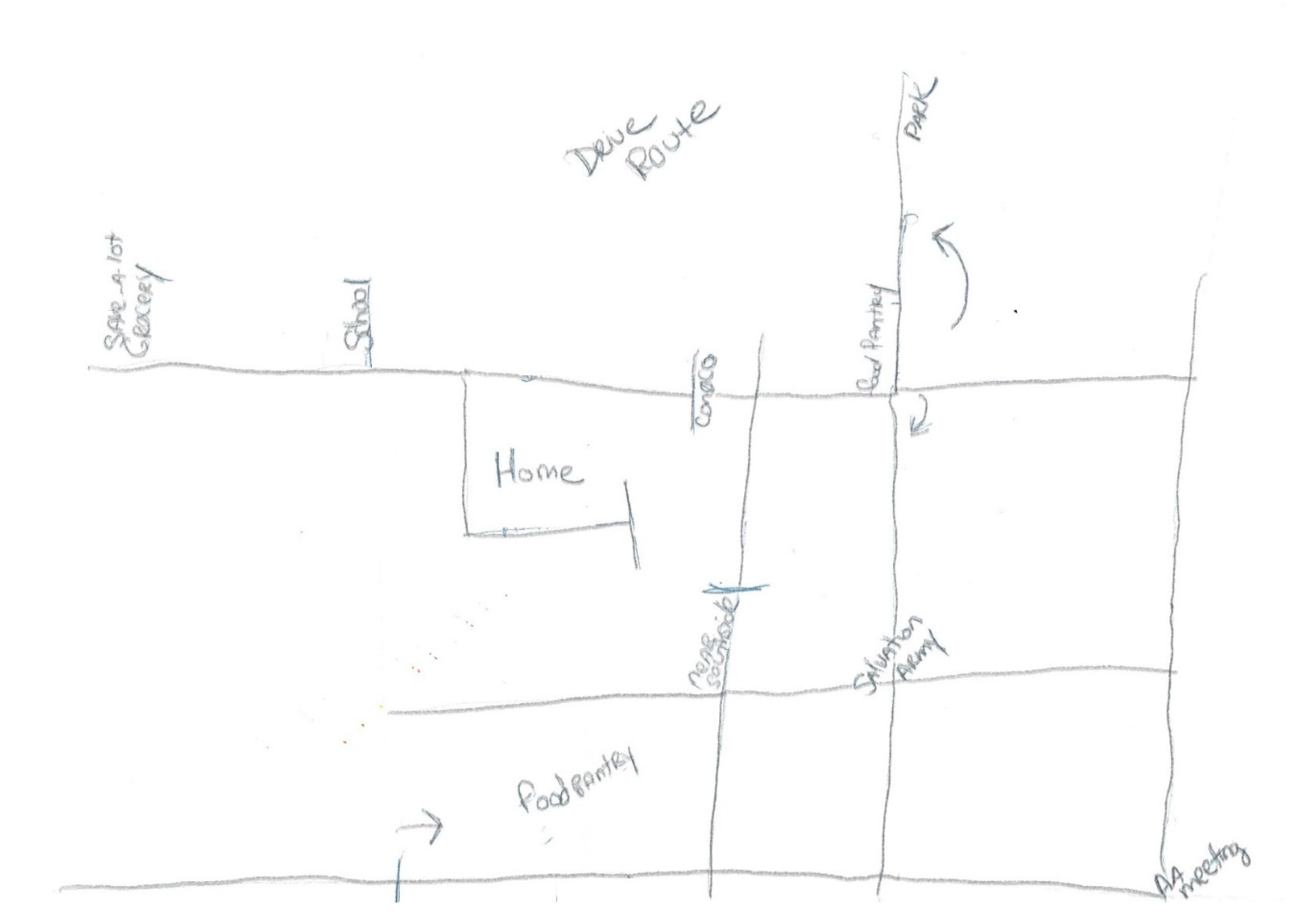

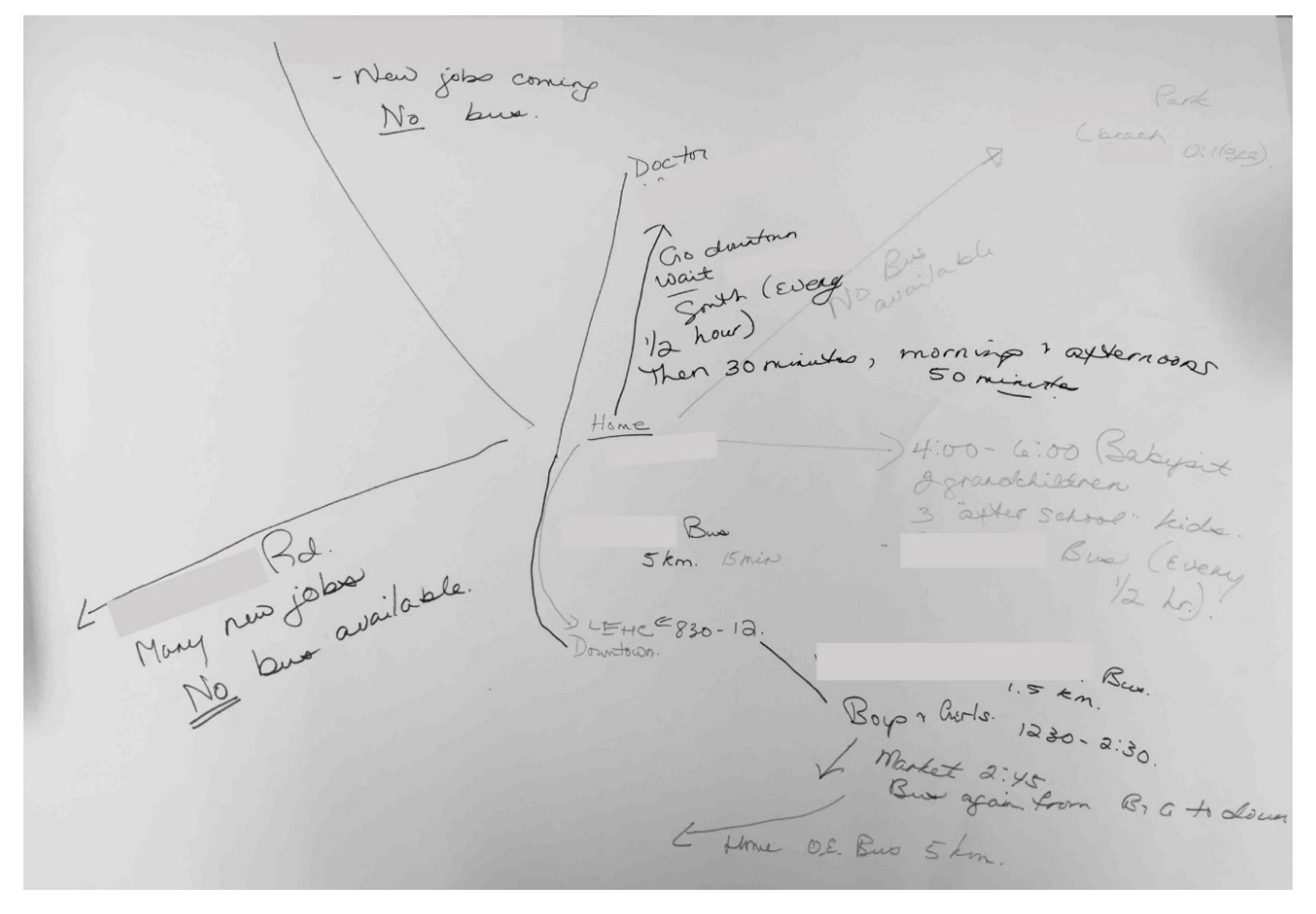

Occupational Maps

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Phase | Participant Type | Interview Question(s) |

|---|---|---|

| I | Organizational stakeholders | From your perspective, how do you define long-term unemployment? |

| II | Front-line service provider | Based on your experiences, how do you define long-term unemployment? Reflecting on your experiences, what are the factors that seem to lead particular clients to experience long-term unemployment? When in the process of working with a client, do you tend to identify or know that the person is likely going to be facing long-term unemployment? |

| III | Long-term unemployed people | At what point did you come to see yourself as experiencing long-term unemployment? Was there a particular event or experience that made you think of your unemployment as long-term? How do you define long-term unemployment? |

References

- Burtless, G. Long-Term Unemployment: Anatomy of the Scourge; Brookings: Washington, DC, USA, 27 July 2012; Available online: https://www.brookings.edu/articles/long-term-unemployment-anatomy-of-the-scourge/ (accessed on 29 July 2020).

- Hornstein, A.; Lubik, T. The rise in long-term unemployment: Potential causes and implications. Econ. Q. 2016, 101, 125–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosanovich, K.; Sherman, E.T. Spotlight on Statistics: Trends in Long-Term Unemployment; U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. Available online: https://www.bls.gov/spotlight/2015/long-term-unemployment/ (accessed on 29 July 2020).

- Kroft, K.; Lange, F.; Notowidigdo, M.J.; Katz, L.F. Long-term unemployment and the great recession: The role of composition, duration dependence, and nonparticipation. J. Labor Econ. 2016, 34, S7–S54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alenda-Demoutiez, J.; Mügge, D. The lure of ill-fitting unemployment statistics: How South Africa’s discouraged work seekers disappeared from the unemployment rate. New Polit. Econ. 2020, 25, 590–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blustein, D.L.; Medvide, M.B.; Wan, C.M. A critical perspective of contemporary unemployment policy and practices. J. Career Dev. 2012, 39, 341–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandolini, A.; Cipollone, P.; Viviano, E. Does the ILO definition capture all unemployment? J. Eur. Econ. Assoc. 2006, 4, 153–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Card, D. Origins of the unemployment rate: The lasting legacy of measurement without theory. Am. Econ. Rev. 2011, 101, 552–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Cranford, C.J.; Vosko, L.F.; Zukewich, N. Precarious employment in the Canadian labour market: A statistical portrait. Just Labour 2003, 3, 6–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dooley, D. Unemployment, underemployment, and mental health: Conceptualizing employment status as a continuum. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2003, 32, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duell, N.; Thurau, L.; Vetter, T. Long-Term Unemployment in the EU: Trends and Policies; Bertelsmann-Stiftung: Gütersloh, Germany, 2016; pp. 1–88. [Google Scholar]

- Karjanen, D. The limits to quantitative thinking: Engaging economics on the unemployed. In Anthropologies of Unemployment; Kwon, J.B., Lane, C.M., Eds.; Cornell University Press; JSTOR: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 34–52. [Google Scholar]

- Kroft, K.; Lange, F.; Notowidigdo, M.J.; Tudball, M. Long time out: Unemployment and joblessness in Canada and the United States. J. Labor Econ. 2019, 37, S355–S397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, J.B.; Lane, C.M. Anthropologies of Unemployment: New Perspectives on Work and Its Absence; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Rothstein, D.S. Monthly Labor Review: An Analysis of Long-Term Unemployment; U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics: Washington, DC, USA, July 2016. Available online: https://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/2016/article/an-analysis-of-long-term-unemployment.htm (accessed on 29 July 2020).

- International Labour Office (ILO). Key Indicators of the Labour Market; ILO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, K.; Tileaga, C.; Cahill, S. Dilemmas of long-term unemployment: Talking about constraint, self-determination and the future. Int. J. Educ. Psychol. Community 2014, 4, 7–33. [Google Scholar]

- Laliberte Rudman, D. Critical discourse analysis: Adding a political dimension to inquiry. In Transactional Perspectives on Occupation; Cutchin, M.P., Dickie, V.A., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 169–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njelesani, J.; Gibson, B.E.; Nixon, S.; Cameron, D.; Polatajko, H.J. Towards a critical occupational approach to research. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2013, 12, 207–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crenshaw, K. Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A Black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. Univ. Chic. Leg. Forum 1989, 1, 139–167. [Google Scholar]

- Laliberte Rudman, D. Occupational terminology: Occupational possibilities. J. Occup. Sci. 2010, 17, 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boland, T. Seeking a role: Disciplining jobseekers as actors in the labour market. Work Empl. Soc. 2016, 30, 334–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazso, A.; McDaniel, S.A. The risks of being a lone mother on income support in Canada and the USA. Int. J. Sociol. Soc. Policy 2010, 30, 368–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haikkola, L. Shaping activation policy at the street level: Governing inactivity in youth employment services. Acta Sociol. 2019, 62, 334–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lightman, E.; Mitchell, A.; Herd, D. Cycling off and on welfare in canada. J. Soc. Policy 2010, 39, 523–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riach, K.; Loretto, W. Identity work and the ‘unemployed’ worker: Age, disability and the lived experience of the older unemployed. Work Employ. Soc. 2009, 23, 102–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silver, S.; Shields, J.; Wilson, S.; Scholtz, A. The excluded, the vulnerable and the reintegrated in a neoliberal era: Qualitative dimensions of the unemployment experience. Soc. Stud. 2009, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schram, S.F. Neoliberalizing the welfare state: Marketing policy/disciplining clients. In The SAGE Handbook of Neoliberalism; Cahill, D., Cooper, M., Konings, M., Primrose, D., Eds.; SAGE: London, UK, 2018; pp. 308–322. [Google Scholar]

- Woolford, A.; Nelund, A. The responsibilities of the poor: Performing neoliberal citizenship within the bureaucratic field. Soc. Serv. Rev. 2013, 87, 292–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laliberte Rudman, D.; Aldrich, R. “Activated, but stuck”: Applying a critical occupational lens to examine the negotiation of long-term unemployment in contemporary socio-political contexts. Societies 2016, 6, 28–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, M. Governing the unemployed self in an active society. Econ. Soc. 1995, 24, 559–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, N.; O’Malley, P.; Valverde, M. Governmentality. Ann. Rev. Law Soc. Sci. 2006, 2, 83–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, M. Ethnographies of neoliberal governmentalities: From the neoliberal apparatus to neoliberalism and governmental assemblages. Foucault Stud. 2014, 11–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boland, T.; Griffin, R. The death of unemployment and the birth of job-seeking in welfare policy: Governing a liminal experience. Ir. J. Sociol. 2015, 23, 29–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laliberte Rudman, D.; Aldrich, R.M. Discerning the social in individual stories of occupation through critical narrative inquiry. J. Occup. Sci. 2017, 24, 470–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soss, J.; Fording, R.C.; Schram, S. Disciplining the Poor: Neoliberal Paternalism and the Persistent Power of Race; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lipsky, M. Street-Level Bureaucracy: Dilemmas of the Individual in Public Services; Russell Sage Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Aldrich, R.M.; Laliberte Rudman, D.; Dickie, V.A. Resource seeking as occupation: A critical and empirical exploration. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2017, 71, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldrich, R.M.; Laliberte Rudman, D. Situational analysis: A visual analytic approach that unpacks the complexity of occupation. J. Occup. Sci. 2016, 23, 51–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldrich, R.M.; Laliberte Rudman, D. Occupational therapists as street-level bureaucrats: Leveraging the political nature of everyday practice. Can. J. Occup. Ther. 2020, 87, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lassiter, L.E. The Chicago Guide to Collaborative Ethnography; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Scanlan, J.N.; Bundy, A.C. Development and validation of the modified occupational questionnaire. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2011, 65, e11e19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huot, S.; Laliberte Rudman, D. Extending beyond qualitative interviewing to illuminate the tacit nature of everyday occupation: Occupational mapping and participatory occupation methods. OTJR Occup. Particip. Health 2015, 35, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laliberte Rudman, D.; Aldrich, R.M.; Grundy, J.; Stone, M.; Huot, S.; Aslam, A. “You got to make the numbers work”: Negotiating managerial reforms in the provision of employment support service. Altern. Routes: J. Cri. Soc. Res. 2020, 28, 47–79. [Google Scholar]

- Hardin, P.K. Constructing experience in individual interviews, autobiographies and on-line accounts: A poststructuralist approach. J. Adv. Nurs. 2003, 41, 536–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huot, S.; Aldrich, R.; Laliberte Rudman, D.; Stone, M. Picturing precarity through occupational mapping: Making the (im)mobilities of long-term unemployment visible. J. Occup. Sci. 2020, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanelli, C.; Laliberte Rudman, D.; Aldrich, R.M. Precarity in the nonprofit employment services sector. Can. Rev. Sociol. 2017, 54, 331–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grundy, J.; Laliberte Rudman, D. Deciphering deservedness: Canadian employment insurance reforms in historical perspective. Soc. Policy. Adm. 2018, 52, 809–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilcock, A.A. Reflections on doing, being and becoming. Aust. Occup. Ther. J. 2002, 46, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilcock, A.A.; Hocking, C. An Occupational Perspective of Health; SLACK Incorporated: Thorofare, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

| Context | Phase | Alias | Organization Type | Length of Experience in Arena at Time of Interview |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Canada | I | Michael | Regional business development organization | 18 years |

| Canada | I | Kim | Provincially funded employment support and training services | 1 year |

| Canada | I | Victoria | Municipal social services | 40 years |

| Canada | I | Alyssa/Lindsey | Provincial employment support and training services | 28 years/20 years |

| Canada | I | Zack | Provincial ministry of training and education | 10 years |

| Canada | I | Ria | Regional employment advisory board | 12 years |

| Canada | I | Jenna | Provincially funded employment support and training services | 6 years |

| United States | I | Charlie | Community college training program | 11 years |

| United States | I | Nick | Municipal social services | 3 months |

| United States | I | Brian et al. | Municipal/State employment support and training services | Varied (group interview) |

| United States | I | Catherine | Municipal/State employment support and training services | 15 years |

| United States | I | Jennifer | Municipal/State employment support and training services | 7 years |

| United States | I | Andrea | Regional training and resource center | 11 years |

| United States | I | Carter | Municipal/State workforce development services | 10 years |

| United States | I | Joe | Non-profit community organization for immigrants | 6 years |

| Canada | II | Emily | Provincially funded employment support and training services (community based) | 24 years |

| Canada | II | Sarah | Provincially funded employment support and training services (community based) | 5 years |

| Canada | II | Dwight | Provincially funded employment support and training services (community based) | 10 years |

| Canada | II | Courtney | Provincially funded employment support and training services (connected with local college) | 5 years |

| Canada | II | Hillary | Provincially funded employment support and training services (connected with local college) | 3 years |

| Canada | II | Natalie | Provincially funded employment support and training services (community based) | 3 years |

| Canada | II | Jerry | Provincially funded employment support and training services (community based) | Unspecified (observation session only) |

| Canada | II | Kate | Provincially funded employment support and training services (community based) | 22 years |

| Canada | II | Kevin | Provincially funded employment support and training services (connected with local college) | 5 years |

| Canada | II | Nicole | Provincially funded employment support and training services (connected with local college) | 15 years |

| Canada | II | Megan | Provincially funded employment support and training services (community based) | 20 years |

| Canada | II | Teresa | Provincially funded employment support and training services (community based) | 9 years |

| United States | II | Marie | Non-profit employment services for domestic violence survivors | 5 years |

| United States | II | Tom | Non-profit employment services for people with disabilities | 10 months |

| United States | II | Bree | Non-profit employment services for cultural groups | 26 years |

| United States | II | Erin | Non-profit employment services for immigrants | 1 year |

| United States | II | Liz | Municipal/State employment services for welfare recipients | 12 years |

| United States | II | Taylor | Non-profit employment services for immigrants | 3 months |

| United States | II | John | Non-profit employment services for community welfare recipients | 5 months |

| Context | Alias | Age | Gender | Partnership Status | Length of Unemploy-Ment | Prior Work Sectors | Data Collection Completed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Canada | George | 40s | Male | Single | 7 years | ICT services | Narrative Interview, Semi-Structured Interview, Time Diaries, Occupational Mapping |

| Canada | Darcy | 50s | Female | Single | 12 years | Admin. MBA | Narrative Interview, Semi-Structured Interview |

| Canada | Helene | 50s | Female | Partnered | 5 years | Admin. | Narrative Interview, Semi-Structured Interview, Time Diaries, Occupational Mapping |

| Canada | Audrey | 28–30 | Female | Partnered | 5 years | Social Services | Narrative Interview, Semi-Structured Interview, Occupational Mapping, Participant Observation |

| Canada | Trevor | 38 | Male | Single | 4 years | Chef services | Narrative Interview, Semi-Structured Interview, Time Diaries |

| Canada | Peggy | 50s | Female | Single | 5 years | Retail | Narrative Interview, Semi-Structured Interview, Time Diaries, Occupational Mapping |

| Canada | Jesse | 30s | Male | Partnered | 3 years | Labor/machinery Oilsands | Narrative Interview, Semi-Structured Interview, Time Diaries, Occupational Mapping |

| Canada | Mark | 58 | Male | Single | 5 years | Manufacturing | Narrative Interview, Semi-Structured Interview, Time Diaries, Occupational Mapping |

| Canada | Jennifer | 30s | Female | Partnered | 4 years | Admin. | Narrative Interview, Semi-Structured Interview, Time Diaries, Participant Observation |

| Canada | Colin | 30s | Male | Single | 6 years | Services (cook/dishwashing) | Narrative Interview, Semi-Structured Interview, Participant Observation, Time Diaries |

| Canada | Pam | 50s | Female | Single | 5 years + | Artist/graphic designer/research | Narrative Interview, Semi-Structured Interview, Time Diaries, Occupational Mapping |

| Canada | Paul | 26 | Male | Partnered | 5 years | Service (restaurants; wait staff/dish washing) | Narrative Interview, Semi-Structured Interview, Occupational Mapping, Time Diaries |

| United States | Cole | 30s | Female | Single | 6 months | Mortgage Lending, Office Admin. | Narrative Interview, Semi-Structured Interview, Occupational Mapping, Time Diaries |

| United States | John | 30s | Male | Single | 4.5 years | Automotive Repair, Illicit Economy | Narrative Interview, Semi-Structured Interview, Occupational Mapping, Time Diaries |

| United States | Dori | 40s | Female | Married | 5 years | Service Economy (Gas Station/Deli Attendant, Exotic Dancing) | Narrative Interview, Semi-Structured Interview, Occupational Mapping, Time Diaries |

| United States | Skip | 50s | Male | Single | 10 years | Landscaping, Horse Training, Restaurant | Narrative Interview, Semi-Structured Interview, Occupational Mapping, Participant Observation |

| United States | Julia | 50s | Female | Single | 1 year | Communications | Narrative Interview, Semi-Structured Interview, Occupational Mapping, Time Diaries |

| United States | Bella | 50s | Female | Single | 2 years | Software Development and Teaching | Narrative Interview, Semi-Structured Interview, Occupational Mapping, Time Diaries |

| United States | Scott | 50s | Male | Married | 1 year | Business Lending | Narrative Interview, Semi-Structured Interview, Participant Observation, Time Diaries |

| United States | Lucy | 50s | Female | Single | 6 months | Event Logistics | Narrative Interview, Semi-Structured Interview, Occupational Mapping, Participant Observation |

| United States | Maria | 40s | Female | Single | 3 years | Engineering | Narrative Interview, Semi-Structured Interview, Occupational Mapping, Time Diaries |

| United States | Cynthia | 50s | Female | Married | 7 months | Human Resources | Narrative Interview, Semi-Structured Interview, Participant Observation, Time Diaries |

| United States | Debra | 30s | Female | Single | 5 years | Cleaning | Narrative Interview, Semi-Structured Interview, Occupational Mapping, Time Diaries |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Aldrich, R.M.; Rudman, D.L.; Park, N.E.; Huot, S. Centering the Complexity of Long-Term Unemployment: Lessons Learned from a Critical Occupational Science Inquiry. Societies 2020, 10, 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc10030065

Aldrich RM, Rudman DL, Park NE, Huot S. Centering the Complexity of Long-Term Unemployment: Lessons Learned from a Critical Occupational Science Inquiry. Societies. 2020; 10(3):65. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc10030065

Chicago/Turabian StyleAldrich, Rebecca M., Debbie Laliberte Rudman, Na Eon (Esther) Park, and Suzanne Huot. 2020. "Centering the Complexity of Long-Term Unemployment: Lessons Learned from a Critical Occupational Science Inquiry" Societies 10, no. 3: 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc10030065

APA StyleAldrich, R. M., Rudman, D. L., Park, N. E., & Huot, S. (2020). Centering the Complexity of Long-Term Unemployment: Lessons Learned from a Critical Occupational Science Inquiry. Societies, 10(3), 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc10030065