Abstract

This paper examines cross-national differences in job preference orientations from the perspective of job quality. In particular, it investigates the extent to which preferences of workers in 25 developed societies are shaped by the intrinsic quality of jobs and its institutional determinants, as highlighted by varieties of capitalism (VoC) and power resources theory (PRT). The study uses multi-level models with country-specific random intercepts fitted to individual data from the International Social Survey Programme’s 2015 Work Orientations module, paired with institutional indicators from various sources. The results show that workers within countries tend to be oriented towards the same types of rewards that their jobs offer, with the intrinsic quality of work standing out as the most important factor of all. This logic extends to the cross-national variation in job preference orientations, which is strongly related to the average intrinsic quality of jobs in national labor markets and its institutional factors emphasized by PRT, rather than VoC.

1. Introduction

The concept of job preference orientations1 has been traditionally employed in the analyses of people’s subjective relationships with their work. Following a classical definition, job preference orientations refer to “the way[s] in which workers order their wants and expectations relative to their employment” [3] (p. 37). Different typologies of orientations have been proposed [7,11,12] but the central distinction is typically made between extrinsic preferences, “in which jobs are valued for their material rewards” [13] (p. 279), and intrinsic preferences, which “reflect the worker’s desire to be stimulated and challenged by the job and to be able to exercise acquired skills at work” [14] (p. 128). The importance of job preferences lies mainly in relation to job quality in general terms, for what constitutes a good job naturally depends on workers’ attitudes [15]. Furthermore, workers’ orientations are important when it comes to their motivation, productivity, well-being [13] and job satisfaction [14,16].

There is a well-established research tradition of job preference orientations, consisting mainly of studies conducted within specific national contexts [3,4,8,11,17], but there is also a growing body of comparative cross-national studies [1,2,5,6,10,13]. At the individual level, researchers have investigated the relationship between workers’ preferences and factors such as socialization practices, life stages, nature of family life and the molding effect of work experience itself [8,13,17]. Comparative studies at the macro level have typically adopted approaches inspired by modernization theory [6,10] and/or a welfare institutional perspective [1,2,5] and attempted to explain the cross-national diversity in job preferences as a function of societies’ development stages or welfare institutional set-ups, respectively. Still, findings with respect to the applicability of these comparative frameworks are at best inconclusive [1,6,10,13].

There is a third, relatively under-investigated, perspective, which looks at differences in workers’ preferences mainly through the prism of job quality. Following the sociological tradition, the term job quality is used to refer to a good intrinsic quality of work [18], such as the ability to use knowledge, skills, autonomy and control, as well as participate in decision-making regarding work organization [15]. Job quality therefore differs from the quality of employment conditions, which reflects the availability of extrinsic job rewards, such as high pay or job security [18]. In line with neo-Marxist thinking, the job quality perspective suggests that people have a natural desire to fulfil themselves through their work. However, if they are in degrading jobs with few opportunities for self-development, they retreat into a state of alienated instrumentalism2 and refocus on priorities outside of work [13]. On the other hand, being in a high-quality job is likely to increase the desire for self-realization, the use of skills and initiative [17]. The few studies which have explored this mechanism have yielded promising results and showed that job quality may be among the most important determinants of individual [17], as well as cross-national, variations in job preferences [2,13]. This paper’s main goal is to corroborate the plausibility of the job quality hypothesis from a comparative cross-national perspective. It is argued that, if job preference orientations are shaped by individuals’ experiences of work quality, their cross-national variation should be explicable by the average job quality found in national labor markets and its institutional determinants. In particular, the study addresses the plausibility of job quality determinants associated with two comparative political economy frameworks, namely, varieties of capitalism (VoC) and power resources theory (PRT). The hypothesis is empirically examined with random intercept multi-level models fitted to individual data from the International Social Survey Programme’s (ISSP) 2015 Work Orientations module, paired with institutional indicators from various sources.

The structure of the paper is as follows. Part one presents theoretical arguments about how job quality shapes workers’ preferences and reviews existing empirical evidence to support this. It then introduces VoC and PRT and explains the institutional differences likely to affect cross-national variations in job preference orientations. Hypotheses are derived thereof, and the methods, data and measures of variables are described in the next section. The empirical analysis results follow, and the paper concludes with a discussion of the findings and their relevance to comparative work orientations research.

2. Theoretical Argument

2.1. Job Preference Orientations and the Intrinsic Quality of Work

A number of different individual factors has been identified as determinants of job preference orientations [8,13,17]. This paper focuses specifically on the effects of workers’ experiences of intrinsic job quality or the lack thereof, which are hypothesized to be of profound importance to preferences regarding work in general.

A theoretical mechanism about how experience with job quality translates into work preferences3 was previously given the term value reinforcement. According to this explanation, workers adapt to the realities of their jobs, so that the initial orientations that led them to make particular job choices are reinforced as a result of those choices [8,20,21,22]. On a similar note, it has been argued that people tend to rationalize their position vis-à-vis their job and demand the greatest quantity of whatever it is the job supplies [23]. The expectation is that workers in high-quality jobs offering intrinsic rewards experience their work as meaningful and develop a sense of responsibility and stronger internal motivation [13]. On the other hand, workers in jobs offering little in the way of intrinsic rewards are assumed to retreat into a state of alienated instrumentalism and lose aspirations for types of work which offer self-development [17].

A number of longitudinal panel studies conducted in the USA seem to unanimously support the plausibility of the reinforcement mechanism in shaping job preferences. Mortimer and Lorence [20] demonstrated that rewarding occupational experiences lead to the reinforcement of the same values that served as the basis for earlier career choices. Johnson [21,22] showed that young adults tend to adjust their work values in a cooling out process as they first gain experiences as adult workers. Other studies showed that reinforcement mechanisms can be extended to explain the changes in work values during the economic recession [24] and even the development of work values across-generations [25].

Results from cross-sectional empirical studies largely confirm the plausibility of this mechanism. In a study from Canada, MacKinnon [4] found that the instrumentalism of industrial workers was a subjective component of work alienation caused by self-estrangement and occupational powerlessness. As shown by Gallie et al. [17] in their study on the changing orientations of British workers between 1992 and 2006, job quality stood out as having particularly strong associations with intrinsic preferences, with effects and explanatory power ahead of the early socialization or material conditions of employment. Additionally, Gesthuizen and Verbakel [2] found, in a multi-level study of 19 European countries, that job autonomy as an individual-level variable was associated with stronger intrinsic and weaker extrinsic preferences.

The logic of value reinforcement has been extended to the macro level too. It has been hypothesized that “an emphasis on high levels of skill and quality production” in the national economy is conducive to “an ethos in which employees attach particular importance to intrinsic characteristics of work” [13] (p. 282). Despite only a few studies testing the relationship cross-nationally, they still yielded promising results. In a study of five European countries, Gallie [13] found that a prevalence of good quality jobs, together with skill-related structural differences, explained the largest part of the distinctively intrinsic orientation of Scandinavian countries. In an alternative model specification from the same study, job quality eliminated country differences entirely. When Gesthuizen and Verbakel [2] replicated the study with a larger comparative design, they found that quality of the labor market was associated with a decrease in extrinsic preferences while intrinsic orientations remained unaffected.

2.2. Comparative Frameworks: VoC and PRT

It seems plausible to assume that job quality is an important factor shaping job preference orientations at both individual and national levels. However, intrinsic job quality and its specific components are not randomly distributed across national political economies; rather, they seem to follow specific institutional logic. VoC and PRT are the main comparative political-economy frameworks which specify the institutional mechanisms responsible for the national diversity in job quality [26]. While, according to the former, job quality varies as a result of the differences in skill requirements, the latter emphasizes the varying strength of organized labor as the dominant factor [27].

VoC assumes that national diversity in job quality is primarily the result of how companies organize and coordinate production. Different strategies require different types of skill assets, which in turn affect “several aspects of work experience […] critical for the quality of employment” [28] (p. 87). Companies in so-called coordinated market economies (CMEs) focus on high-quality diversified production, as they depend on skilled labor with a great amount of company- and industry-specific skills [27]. Complex and knowledge-intensive production translates into high task discretion [5]. Since employees work in autonomous ways which are difficult and costly to monitor, consensus-based approaches to decision-making proliferate [29]. The so-called liberal market economies (LMEs) provide a radically different picture of job quality [28]. This is linked with the production strategy based on an ability to flexibly react to market signals and to adjust employee numbers accordingly [5,27], which requires a workforce with general skills that are readily available on the market and transferable across firms. Hence, companies in LMEs favor organizational structures that allow high levels of unilateral managerial control which lead to employees having less influence in the decision-making process [27,29].

According to PRT, divisions among developed societies reflect the balance of class power between employers and workers, manifested in the strength of labor unions and political parties [30]. Relative power resources determine the ability of workers to shape the conditions under which the cooperation necessary for production occurs [31]; hence, the extension of the framework to job quality. Intrinsic job quality is, from a labor union’s perspective, both a power resource and an aim of specific importance. First, this is because it increases employees’ well-being and satisfaction [18], reduces stress and enhances opportunities for skill development [32]. Second, it contributes to information asymmetry and increases employers’ motivation to invest in long-term employment contracts [27]. Finally, job quality empowers workers whereby they are able to resist restrictive employee control systems [26].

Available comparative studies show that the institutional differences highlighted by both theories are related to various aspects of job quality and their cross-national variation. However, the evidence with respect to VoC is slightly less consistent, with some studies pointing to PRT as being a better explanatory framework. For instance, Esser and Olsen [26] showed that both the specificity of skill structure and the power of workers are positively related to job autonomy. Edlund and Grönlund [27], on the other hand, demonstrated that the relationship between autonomy and skill specificity is spurious and disappears when the strength of organized labor is accounted for. Similarly, Gallie [28] discovered no evidence that cross-national differences in task discretion, job variety and self-development opportunities would follow institutional distinctions highlighted by VoC, while finding PRT explanations more convincing. The same author also empirically demonstrated that trade unionism is highly correlated with task discretion [33] and a higher employee control [34].

3. Hypotheses

This paper aims to contribute to the comparative work orientations research by empirically examining the interrelatedness between job preference orientations and job quality from a multi-level cross-national perspective. Given the presented theoretical arguments and available evidence, a set of testable hypotheses can be devised.

Hypothesis 1a.

First, it is expected that job quality at an individual level will be related to job preference orientations in a value-reinforcing way, i.e., that it will be positively associated with intrinsic-type preferences and negatively associated with extrinsic ones.

Hypothesis 1b.

The first hypothesis also expects job quality to be a factor of the utmost importance to the formation of job preference orientations. Therefore, its effect is expected to be relatively larger than that of other predictors or controls.

Hypothesis 2.

The average job quality of national labor markets is expected to mirror the effect of its individual counterpart and to be associated with workers’ stronger average intrinsic, rather than extrinsic preferences.

Hypothesis 3.

Seen from the perspective of VoC, national economies relying on specific skill assets are expected to emphasize stronger intrinsic work valuations as a result of a generally higher quality of work.

Hypothesis 4.

With respect to PRT, it is expected that employees in countries with encompassing labor movements will be in a better position with respect to many job quality aspects and therefore express stronger intrinsic, rather than extrinsic, valuations of work.

Hypothesis 5.

Finally, since studies indicate that PRT might do a better job in explaining cross-national differences in job quality than VoC, predictors related to the former framework are expected to have a stronger relative effect and explanatory power.

4. Data

The paper uses individual survey data from the ISSP 2015 Work Orientations module [35,36]. The original data set was further reduced to include only national samples that had complete sets of all relevant macro level indicators. Within those countries, the focus was narrowed to sub-populations reported as being currently in paid employment. After the cases with missing values were deleted, the final sample consisted of 15,163 individuals clustered in 25 countries4.

5. Methods

All models presented in the study were estimated as multi-level regressions with country-specific random intercepts. Parameter estimates were obtained with a restricted maximum likelihood, which is a more accurate method when the number of level-two units is relatively small [37,38]. Given the fact there are 25 country-clusters in the analyzed data, the estimation of group-level parameters and variance components should still be reliable [39,40]. To enhance the accuracy and interpretability of the estimates, all predictors were either group- or grand mean-centered, depending on the specific model of interest [41]. Continuous variables at both levels were additionally standardized by twice their standard deviation, so that the relative strength of their relationship with the outcome could be directly compared with each other and with unstandardized binary predictors [42].

6. Variables

6.1. Dependent Variable

The dependent variable is a multi-point scale capturing the relative importance of intrinsic and extrinsic job preferences to a person’s job preference orientation [13]. The items used for its construction were introduced in the questionnaire with the instruction: “For each of the following, please tick one box to show how important you personally think it is in a job.” Responses were reverse-coded so that the scales ranged between 1 (“Not important at all”) and 5 (“Very important”).

The results from an exploratory factor analysis5 suggested that “job security”, “high income” and “good opportunities for advancement” comprise the extrinsic dimension of the job preference orientations scale (alpha reliability6 0.57). The intrinsic dimension7, on the other hand, consisted of “an interesting job”, “a job that allows someone to work independently” and “a job that allows someone to decide their hours or days of work” (alpha reliability 0.58). The composite scale was calculated in two steps. First, the average scores were computed for each of the dimensions separately. Next, the mean extrinsic score was subtracted from the intrinsic one, so that the resulting job preference orientations scale theoretically ranged between −4 and 4. While positive values indicate a higher relative importance accorded to intrinsic aspects of work, negative values correspond to a higher valuation of extrinsic rewards. Such a composite measure is not only analytically efficient, but can also account for halo effects resulting from the varying degrees of willingness among respondents in different countries to use extreme categories of the scale [6,13,34].

6.2. Independent Variables at the Individual Level

To capture the overall intrinsic quality of the respondent’s work, a summative index of job quality was constructed (cf. with similar indices used in [13,17,18,44]). The index consisted of four items reflecting the respondent’s assessment of whether her job is interesting, if she can work independently, if she is free to decide how her daily work is organized, and if she can decide her own working hours. For each component, dichotomous variables were created with a value of 1 indicating that a given facet is, to some extent, present in the respondent’s current job, and 0 otherwise. The sum of the four items was used as an overall measure of job quality (alpha reliability 0.62).

To assess whether the logic of value reinforcement also applies to the quality of employment conditions, subjectively assessed income and job security were selected as additional controls. The measure of income was based on the respondent’s agreement with the statement “My income is high”, expressed on a reverse-coded scale ranging between 1 (“Strongly disagree”) and 5 (“Strongly disagree”). Job security was captured by agreement with the statement “My job is secure”, expressed on an identical scale.

Additionally, controls for standard demographic and socioeconomic characteristics were used. The demographic information obtained included gender, age and education measured in years of formal schooling. The location in the structure of work was captured by dummies for self-employment, supervising responsibilities and part-time work, defined as less than 30 weekly hours in the main job.

Finally, to avoid ecological fallacies and to be able to test macro influences over and above the micro level, two controls related to the main institutional frameworks were included too. The VoC model’s control for the specificity of individuals’ skills was captured by the “s1” relative skill specificity measure suggested by Iversen and Soskice [45]. The measure is derived from the ISCO-88 classification of occupations and captures how specialized an individual’s skills are relative to the total skills she possesses8. Values of the measure obtained from Cusack et al. [46] were assigned to individual respondents based on their ISCO-88 codes. As for the PRT, a simple binary variable indicating respondents’ union membership statuses was included9.

6.3. Independent Variables at the Country Level

First, to illustrate the extent to which there is cross-national variation in job preferences related to differences in intrinsic quality of work, a country-level measure of job quality was constructed. The predictor was obtained simply by averaging the individual job quality variable at the level of countries.

Two indicators of countries’ average skill specificity10 were selected to capture the skill diversity among national political economies, expected by the VoC framework. The first indicator is based on the aforementioned “s1” relative skill specificity measure [45,46], the values of which were simply averaged at country level. Thus, higher values of this aggregated measure should reflect a higher average specificity of skill assets, utilized in production in a given country.

The second indicator of skill specificity is the median enterprise tenure measured in years11. The indicator is based on the idea that investment in specific skills increases opportunity costs with regard to the termination of the employment contract for both employers and employees. Therefore, a higher average specificity of skills is expected to be reflected in longer median tenure rates in a country [47]. Indicator values for the majority of countries were extracted from the 2015 European Working Conditions Survey [49]. US data came from the 2014 General Social Survey [50], values for Japan were gathered from the 2012 Japan General Social Survey [51], and data for Russia and Israel were obtained from the 2010 European Social Survey [52].

With regard to PRT, two indicators of unions’ capacity to organize large amounts of workers were selected [53]. The first indicator was trade union density, measured as a percentage of the labor force organized into unions. The second indicator was bargaining coverage, defined as the proportion of contracts in which wages are determined in collective bargaining. Both indicators were obtained from the International Labour Organization database ILOSTAT [54] and their values correspond to 2015 or the most recent available year12.

7. Results

7.1. Country Differences

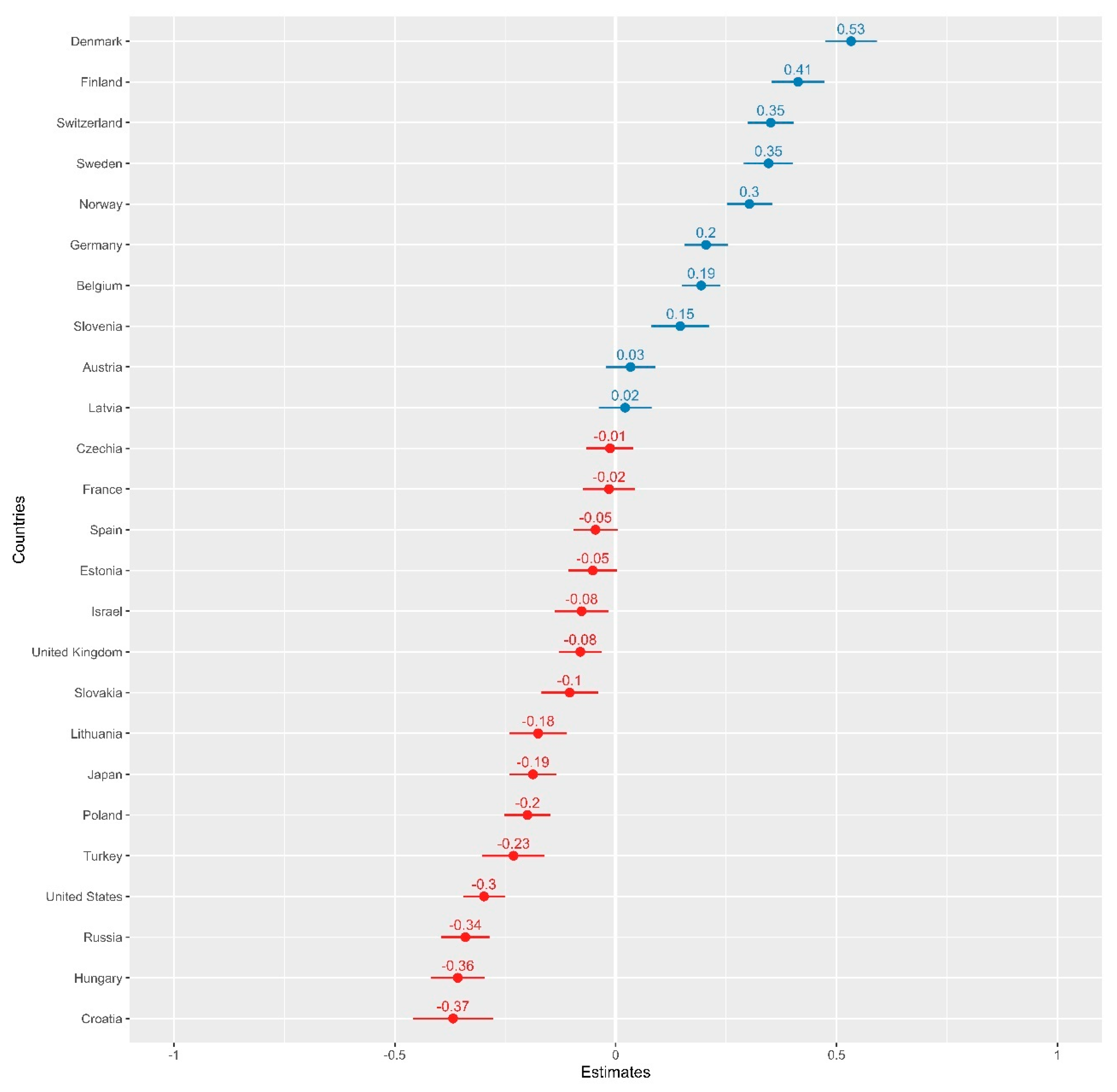

In the first step, a null model containing only country-specific random intercepts was applied to the data. According to the intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC) calculated from the model, 12% of the overall variance in job preference orientations occurs between countries, i.e., it is explained by the grouping structure in the population. Figure 1 displays the country effects from that model, along with their 95% confidence intervals. The effects are arranged around a mean job preference orientations score of zero, corresponding to extrinsic and intrinsic preferences which are of relatively equal importance. Countries with a relatively stronger intrinsic orientation are located on the right half of the figure, while the predominantly extrinsically oriented are placed in the left half. A relatively stronger extrinsic orientation appears to be more common and can be found in 15 countries. Central and Eastern European countries (i.e., Croatia, Hungary and Russia), together with the US and Turkey, dominate the group of extrinsically oriented societies. Workers in the remaining 10 countries are relatively more intrinsically oriented, and this type of orientation is strongest in Scandinavian countries (i.e., Denmark, Finland, Sweden and Norway) and Switzerland. The cluster pattern that emerged from the null model is roughly consistent with earlier results from comparative research on both job preferences and job quality. Workers in Scandinavian countries were repeatedly found both to be the most strongly intrinsically oriented [5,13] and reported distinctively high levels of work quality aspects such as autonomy [26], work task quality [44], task discretion [33] and job control [34]. These preliminary results seem to support the idea of interrelatedness between job quality and job preference orientations.

Figure 1.

Effect of country-specific random intercepts on job preference orientations (based on Model A1, Table 1).

7.2. Individual-Level Regression Results

In the next step, the fixed effects of individual-level predictors and controls were estimated. In line with the suggestions formulated by Enders and Tofighi [41], predictors were group mean-centered at the country level, as the procedure leads to purer estimates of individual-level regression coefficients. Results from this model are summarized in Model A2 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Effects of individual-level characteristics on job preference orientations; multi-level regression.

Positive coefficients should be interpreted as strengthening the relative intrinsic orientation. Negative coefficients, on the other hand, can be read as strengthening relative extrinsic orientations. When keeping other predictors and controls constant, intrinsic job quality is most strongly correlated with job preference orientations. The effect is significant and positive, which means that workers who enjoy a high levels of job quality tend to be the most intrinsically oriented ones. The effect of employment conditions is negative and much weaker. Having a secure job, ceteris paribus, increases the relative strength of the extrinsic orientation. However, the effect of a high income is not statistically significant. The results provide evidence that value reinforcement is a plausible explanatory mechanism for the individual differences in job preference orientations. As expected (Hypothesis 1a), workers tend to value the job characteristics they experience positively in their actual job: high employment quality is correlated with a stronger relative extrinsic orientation, while intrinsic job quality reinforces intrinsic orientations. As job quality has the strongest relative effect of all predictors (Hypothesis 1b), an individual’s orientation is likely to be intrinsic rather than extrinsic, even if she enjoys a full range of favorable employment conditions and job quality rewards.

7.3. Country-Level Regression Results

To test the impact of intrinsic job quality and its institutional determinants on cross-national differences in job preference orientations, country-level predictors were added to the model containing the full range of individual-level predictors and controls (see Table 1). All predictors were grand mean-centered, since this procedure is suggested when the relationship between the outcome and level-two predictors is of primary interest, while individual-level variables are used as controls [41].

Model B1 (Table 2) shows that the effect of job quality is statistically significant and positive, indicating that workers from countries where jobs offer more intrinsic rewards tend to emphasize intrinsic rather than extrinsic job preferences. The predictor has a remarkable explanatory power, and its inclusion in the equation alone results in a 58% reduction in the initial variance share at the country level (compared to Model A1, Table 1). The results seem to indicate that the job quality hypothesis holds true at the individual level and at the societal level (Hypothesis 2).

Table 2.

Effects of intrinsic job quality and its determinants, as highlighted by varieties of capitalism (VoC) and power resources theory (PRT), on job preference orientations—a multi-level regression.

Model B2 (Table 2) shows that median tenure as a proxy for skill specificity has only a small positive effect which is not even statistically significant. This is not the case for the latter of the two VoC-related predictors. Model B3 (Table 2) suggests that average skill specificity is significantly related to job preference orientations, but the direction of the coefficient is (contrary to expectations) negative. The model implies that workers in countries with relatively more specific skills are oriented relatively more extrinsically than intrinsically. As the indicator measures skill specificity relative to the general skill level, it also suggests that a stronger relative intrinsic orientation is (contrary to expectations) associated with higher general, rather than specific, skills. Even though the predictor eliminates 33% of the initial ICC value, its explanatory power is comparatively weaker than that of aggregated job quality. All in all, the results do not seem to support the expectation that skill specificity plays a decisive role in determining job preference orientations (Hypothesis 3).

Models B3 and B4 (Table 2) show that empirical support in favor of PRT is much more reliable. Consistent with expectations (Hypothesis 4), both predictors of unions’ strength, be it bargaining coverage or union density, are positively related to job preference orientations with effects comfortably higher than zero. In other words, the stronger the organized labor, the more intrinsically oriented individuals in a country are. Further, the explanatory power of this framework is higher than that of VoC. Each predictor alone has a stronger relative effect than skill specificity, and while bargaining coverage leads to a 58% reduction in the ICC, union density reduces it by almost 67%. Still, also according to the former criterion, union density seems to be associated with job preference orientations even more strongly than bargaining coverage.

In the next step, the explanatory power of two frameworks was directly compared. This was done first by fitting a model containing VoC and PRT predictors which are most strongly related to job preference orientations, i.e., skill specificity and union density (Model C1, Table 3). The model provides additional support in favor of PRT by showing that union density alone accounts for the effect of skill specificity, while losing only a small portion of its initial strength (7%).

Table 3.

Effects of skill specificity and union density on job preference orientations, controlling for country-level job quality—a multi-level regression.

Both skill specificity and union density were then estimated individually, together with the country-level job quality predictor in one equation (Models C2 and C3, Table 3). This was done in order to assess the extent to which frameworks’ explanatory powers are due to their capability to explain cross-national variation in job quality. Model C2 demonstrates that the skill specificity predictor again loses its effect and becomes statistically insignificant, even if job quality is controlled for. This indicates that any effect of skill specificity on job preference orientations is in fact fully mediated through job quality and disappears once this part of variance is removed. When an analogical operation is performed on union density (Model C3, Table 3), the outcome is rather different. The coefficient is substantially reduced (33%) but retains statistical significance. Even though the effect of union density is also mediated by job quality, this mediation seems to be only partial.

Finally, no major differences were observed when the effects of all three macro predictors were estimated together (Model C4, Table 3). The coefficient of union density loses approximately 27% of its initial effect but remains significant. On the contrary, the effect of skill specificity continues to be indistinguishable from zero. Taken together, the results from all country-level models unanimously point to PRT as being a more plausible explanatory framework for cross-national variation in job preference orientations than VoC (Hypothesis 5).

These results fully support most of the job quality hypotheses formulated earlier. Not only is intrinsic job quality crucial for the orientations of individual workers, differences in job quality at the societal level play a vital role in explaining cross-national variations in job preference orientations. The superior explanatory performance of PRT, compared to VoC, appears to stem from the fact that this framework more accurately points to the mechanisms that are primarily responsible for differences in the availability of intrinsic job quality rewards among countries. However, since the predictor retained a substantial part of its initial effect size even after job quality at both levels was controlled for, it is possible that the impact of unionization on job preferences may be even more complex (see the Discussion section).

8. Discussion and Conclusions

The paper’s main goal was to examine cross-national differences in job preference orientations from the relatively under-investigated perspective of job quality, i.e., a good intrinsic quality of work. The effect of job quality and its institutional determinants underscored by VoC and PRT was investigated using the 2015 ISSP Work Orientations data, paired with a set of macro level indicators. All models presented in the paper were fitted as multi-level regressions with country-specific random intercepts. Two methodological improvements to similarly designed previous studies were introduced: macro predictors were selected so that the number of countries fulfilled the requirements for a reliable estimation of country effects [39,40], while the standardization of predictors made a direct comparison with their possible relative effect [41,42].

Individual-level results showed that job rewards are related to job preference orientations in a value-reinforcing manner, i.e., workers tend to emphasize the importance of precisely those aspects of work they currently enjoy in their jobs. However, intrinsic job quality stood out as having the strongest association, outweighing the effect of good employment conditions such as high income or job security. That said, if a job offers autonomy, stimulating content and flexibility and is well-paid and secure, workers will be relatively more intrinsically, rather than extrinsically, oriented.

The analysis further demonstrated that the logic of reinforcement also extends to cross-national comparisons. National labor markets with a higher intrinsic quality of jobs were shown to have relatively more intrinsically oriented workers than societies with a lower quality of work. This explanation gained additional support when the plausibility of two comparative frameworks was examined. With respect to VoC, the average specificity of skill assets utilized in the production was found to be weakly related to job preference orientations and in direct contrast to what the theory expected. Furthermore, the relationship disappeared completely when controlling for either country-level job quality or the strength of organized labor. Indicators related to PRT were, on the other hand, more strongly and consistently related to workers’ preferences. Extensive union representation was found to shift workers’ preferences towards the intrinsic pole of the continuum, and this effect proved to be robust, even when skill specificity with job quality was included in the same model. The results indicated that PRT is a more powerful explanatory framework for cross-national differences in job preference orientations than VoC, and that this is likely due to its superior capability to explain cross-national differences in job quality [27,28].

The effect of unionization on job preferences is hardly surprising, especially given the well-documented association between a strong union presence in a country and a better overall intrinsic work quality, be it in terms of autonomy, task discretion, or job control [26,33,34]. In turn, improvements in the quality of work achieved by unions are likely to be translated into workers’ stronger intrinsic preferences, in line with the logic of value reinforcement. Moreover, unions may also influence the strength of intrinsic preferences beyond their immediate effect on quality of work. If initiated by strong unions, policies aimed at improving job quality may contribute to a “shift in climate of ideas” [44] (p. 64) and create an ethos whereby a high priority is given to work quality and employees put specific emphasis on the intrinsic aspects of jobs [13] (p. 282). However, it also seems possible to assume that both a strong presence of unions and emphasis on the intrinsic valuation of work can at least partly result from a common underlying factor of cultural nature, i.e., a general belief about the positive value of work and its importance. Where such beliefs prevail, workers may be naturally inclined to perceive work as intrinsically important, while being at the same time more willing to organize for the sake of job quality and improving working conditions.

This paper contributes to the comparative work orientations research in two respects. First, it provides evidence which interconnects with results from cross-national studies on job preferences and job quality [2,13], and with those on the intrinsic quality of work and its institutional determinants [13,27,34]. It illustrates the extent of the interrelatedness between job preferences and job quality by showing that the cross-national distribution of both follows a similar theoretical logic to that of PRT. The results suggest that cross-national variations in job preferences do not follow an autonomous cultural logic. Instead, preferences of workers from different societies can only be comprehended and explained in the context of the material conditions of their work, its organization and quality.

The second way in which this study contributes to the body of knowledge on comparative work orientations is more substantial. Even though the evidence is not strong enough to claim that extrinsic orientation is a result of degrading working conditions [4], it suggests that this type of orientation may indicate the absence of intrinsic job rewards known to be crucial for workers’ well-being and satisfaction [15,18,32]. Similarly, a stronger relative intrinsic orientation can be thought of as being an indication of the presence of such favorable aspects of work [13,17], in addition to being a crucial factor of economies’ innovation potential, competitiveness and sustainability [7].

Further research is recommended to examine the implications arising from the presented results. The first issue worthy of scientific attention concerns the potential existence of a mediating relationship between job quality and other types of macro determinants, which were previously demonstrated to affect job preferences. If country characteristics such as socioeconomic development, income inequality or generous welfare policies [1,2,10] are, in fact, correlated with the average quality of jobs, their effect might be partly mediated by this relationship. Another question relates to how job quality affects the social dimension of job preference orientations, which was beyond the scope of this study. Future research could examine whether value reinforcement also works in the case of this type of orientation and, if so, whether the strength of organized labor and/or dominant types of skill assets affect(s) conditions for the satisfaction of this preference orientation. Finally, researchers are encouraged to examine how job preferences are affected by changes in union membership over time. If reinforcement logic holds and the decrease in unionization in the recent decades was mirrored in the erosion of job quality, the data should indicate a devaluation of intrinsic rewards among workers and/or an increase in the emphasis put on extrinsic preferences. Such strengthening of extrinsic preferences in the future can be further reinforced by intergenerational population replacement, as more recent cohorts seem to demonstrate stronger extrinsic valuations of work than their predecessors [55].

A few limitations should be taken into consideration when interpreting the presented results. The first issue concerns the cross-sectional character of the analyzed data, which rules out any possibility for the causal interpretations of the results. However, they still provide valuable empirical evidence for the assessment of the presented theoretical arguments. The second limitation refers to the specific mode of the operationalization of job preference orientations used in this paper. The composite measure of extrinsic and intrinsic preferences captures the relative differences between the two dimensions, i.e., the extent to which one is more or less important than the other. The reported results may therefore differ somewhat in comparison with other studies which use absolute measures instead.

Funding

The APC was funded by the University of Bergen fund for Open Access publishing.

Acknowledgments

A substantial part of this article has been written during the author’s research stay at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, supported by the J.W. Fulbright Commission for Educational Exchange in the Slovak Republic. The insightful comments of Arne L. Kalleberg, Hans-Tore Hansen, and Ole Johnny Olsen and are gratefully acknowledged.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Exploratory factor analysis solution (three factors, principal axis factoring, promax rotation).

Table A1.

Exploratory factor analysis solution (three factors, principal axis factoring, promax rotation).

| Job Preferences | Factor Loadings | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Social Orientation | Intrinsic Orientation | Extrinsic Orientation | |

| High income | −0.19 | −0.02 | 0.78 |

| Advancement opportunities | 0.02 | 0.15 | 0.51 |

| Job security | 0.10 | −0.08 | 0.43 |

| Work independently | −0.10 | 0.92 | −0.12 |

| Interesting job | 0.11 | 0.42 | 0.08 |

| Decide hours/days of work | 0.03 | 0.41 | 0.02 |

| Useful to society | 0.85 | −0.06 | 0.00 |

| Help others | 0.80 | 0.07 | −0.07 |

| Cronbach’s α | 0.80 | 0.58 | 0.57 |

Table A2.

Descriptive statistics.

Table A2.

Descriptive statistics.

| Observations | Mean | Standard Deviation | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable | ||||

| Job preference orientation score | 18,390 | −0.10 | 0.75 | 8 (−4 to 4) |

| Individual-level independent variables | ||||

| Woman | 18,957 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 1 (0–1) |

| Age | 18,898 | 43.59 | 12.40 | 69 (17–86) |

| Education | 18,697 | 13.69 | 3.61 | 58 (0–58) |

| Part-time | 18,062 | 0.11 | 0.31 | 1 (0–1) |

| Self-employed | 18,644 | 0.12 | 0.33 | 1 (0–1) |

| Supervising | 18,529 | 0.27 | 0.44 | 1 (0–1) |

| Union membership | 18,566 | 0.26 | 0.44 | 1 (0–1) |

| Skill specificity | 17,791 | 1.17 | 0.68 | 3.63 (0.48–4.11) |

| Income | 18,318 | 2.82 | 1.09 | 4 (1–5) |

| Job security | 18,255 | 3.78 | 1.11 | 4 (1–5) |

| Job quality | 17,977 | 2.63 | 1.29 | 4 (0–4) |

| Country-level independent variables | ||||

| Job quality | 18,957 | 2.61 | 0.51 | 1.62 (1.74–3.35) |

| Median tenure | 18,957 | 6.70 | 1.47 | 5 (5–10) |

| Skill specificity 2 | 18,957 | 1.19 | 0.12 | 0.46 (1.01–1.47) |

| Union density | 18,957 | 26.02 | 19.68 | 64.1 (4.5–68.6) |

| Bargaining coverage | 18,957 | 48.09 | 31.54 | 92.9 (5.6–98.5) |

Table A3.

Country characteristics.

Table A3.

Country characteristics.

| Country | N | Job Preference Orientation | Job Quality (0–4) | Median Tenure (years) | Skill Specificity (0.48–2.97) | Bargaining Coverage (%) | Union Density (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Austria | 594 | −0.06 | 2.91 | 7 | 1.10 | 98.00 | 27.40 |

| Belgium | 989 | 0.10 | 2.85 | 8 | 1.10 | 96.00 | 54.20 |

| Croatia | 221 | −0.48 | 2.08 | 8 | 1.17 | 48.20 | 26.70 |

| Czechia | 670 | −0.11 | 2.54 | 6 | 1.29 | 46.30 | 12.00 |

| Denmark | 543 | 0.44 | 3.31 | 6 | 1.01 | 84.00 | 68.60 |

| Estonia | 611 | −0.15 | 2.38 | 6 | 1.33 | 18.60 | 4.50 |

| Finland | 528 | 0.32 | 3.15 | 10 | 1.17 | 89.30 | 66.50 |

| France | 538 | −0.11 | 2.77 | 8 | 1.10 | 98.50 | 7.90 |

| Germany | 780 | 0.11 | 3.18 | 8 | 1.16 | 56.80 | 17.60 |

| Hungary | 515 | −0.46 | 1.95 | 6 | 1.34 | 22.80 | 9.40 |

| Israel | 514 | −0.18 | 2.61 | 6 | 1.06 | 26.10 | 25.00 |

| Japan | 667 | −0.29 | 1.81 | 10 | 1.08 | 16.80 | 17.40 |

| Latvia | 524 | −0.08 | 2.36 | 5 | 1.36 | 14.80 | 12.60 |

| Lithuania | 437 | −0.28 | 2.31 | 6 | 1.33 | 7.10 | 7.90 |

| Norway | 718 | 0.21 | 3.11 | 6 | 1.09 | 67.00 | 52.50 |

| Poland | 695 | −0.30 | 1.80 | 5 | 1.47 | 17.20 | 12.10 |

| Russia | 637 | −0.44 | 1.76 | 6 | 1.27 | 22.80 | 30.50 |

| Slovakia | 459 | −0.20 | 2.41 | 6 | 1.24 | 24.40 | 11.20 |

| Slovenia | 442 | 0.05 | 2.92 | 10 | 1.31 | 67.50 | 25.10 |

| Spain | 760 | −0.14 | 2.54 | 7 | 1.35 | 76.90 | 13.90 |

| Sweden | 600 | 0.25 | 3.19 | 6 | 1.05 | 90.00 | 67.00 |

| Switzerland | 693 | 0.26 | 3.35 | 6 | 1.08 | 49.20 | 15.70 |

| Turkey | 375 | −0.33 | 1.74 | 5 | 1.23 | 5.60 | 8.00 |

| United Kingdom | 806 | −0.18 | 2.87 | 6 | 1.12 | 27.90 | 24.70 |

| United States | 847 | −0.40 | 3.00 | 5 | 1.18 | 11.80 | 10.60 |

References

- Esser, I.; Lindh, A. Job preferences in comparative perspective 19892–015: A multidimensional evaluation of individual and contextual influences. Int. J. Sociol. 2018, 48, 142–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gesthuizen, M.; Verbakel, E. Job preferences in Europe: Tests for scale invariance and examining cross-national variation using EVS. Eur. Soc. 2011, 13, 663–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldthorpe, J.H.; Lockwood, D.; Bechhofer, F.; Platt, J. The Affluent Worker: Industrial Attitudes and Behaviour; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Mackinnon, M.H. Work instrumentalism reconsidered: A replication of Goldthorpe’s Luton project. Br. J. Sociol. 1980, 31, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berglund, T. Work orientations in Western Europe and the United States. In Commitment to Work and Job Satisfaction: Studies of Work Orientations; Furåker, B., Håkansson, K., Karlsson, J.C., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 47–66. [Google Scholar]

- De Witte, H.; Halman, L.; Gelissen, J. European work orientations at the end of the Twentieth Century. In European Values at the Turn of the Millennium; Arts, W., Halman, L., Eds.; BRILL: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2004; pp. 255–279. [Google Scholar]

- Ester, P.; Mohler, P.; Vinken, H. Eroding work values? In Globalization, Value Change, and Generations. A Cross-National and Intergenerational Perspective; Ester, P., Braun, M., Mohler, P., Eds.; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2006; pp. 89–113. [Google Scholar]

- Kalleberg, A.L.; Marsden, P.V. Changing work values in the United States, 1973–2006. Soc. Sci. Res. 2013, 42, 255–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalleberg, A.L.; Stark, D. Career strategies in capitalism and socialism: Work values and job rewards in the United States and Hungary. Soc. Forces 1993, 72, 181–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parboteeah, K.P.; Cullen, J.B.; Paik, Y. National differences in intrinsic and extrinsic work values: The effects of post-industrialization. Int. J. Cross Cult. Manag. 2013, 13, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halaby, C.N. Where job values come from: Family and schooling background, cognitive ability, and gender. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2003, 68, 251–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, M. Gender, Work orientations and job satisfaction. Work Employ. Soc. 2015, 29, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallie, D. Welfare regimes, employment systems and job preference orientations. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 2007, 23, 279–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalleberg, A.L. Work values and job rewards: A theory of job satisfaction. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1977, 42, 124–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalleberg, A.L. Good Jobs, Bad Jobs: The Rise of Polarized and Precarious Employment Systems in the United States, 1970s–2000s; Russell Sage Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, A.E. Your money or your life: Changing job quality in OECD countries. Br. J. Ind. Relat. 2005, 43, 377–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallie, D.; Felstead, A.; Green, F. Job preferences and the intrinsic quality of work: The changing attitudes of British employees 19922–006. Work Employ. Soc. 2012, 26, 806–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallie, D. Direct participation and the quality of work. Hum. Relat. 2013, 66, 453–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, T.J. Sociology, Work and Industry; Taylor & Francis: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Mortimer, J.T.; Lorence, J. Work experience and occupational value socialization: A longitudinal study. Am. J. Sociol. 1979, 84, 1361–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.K. Job values in the young adult transition: Change and stability with age. Soc. Psychol. Q. 2001, 64, 297–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.K. Change in job values during the transition to adulthood. Work Occup. 2001, 28, 315–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argyris, C. Integrating the Individual and the Organization; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, M.K.; Amber Sage, R.; Mortimer, J.T. Work values, early career difficulties, and the U.S. economic recession. Soc. Psychol. Q. 2012, 75, 242–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.K.; Mortimer, J.T. Reinforcement or compensation? The effects of parents’ work and financial conditions on adolescents’ work values during the Great Recession. J. Vocat. Behav. 2015, 87, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esser, I.; Olsen, K.M. Perceived job quality: Autonomy and job security within a multi-level framework. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 2012, 28, 443–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edlund, J.; Grönlund, A. Class and work autonomy in 21 countries. A question of production regime or power resources? Acta Sociol. 2010, 53, 213–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallie, D. Production regimes and the quality of employment in Europe. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2007, 33, 85–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, P.A.; Soskice, D. An introduction to varieties of capitalism. In Varieties of Capitalism: The Institutional Foundations of Comparative Advantage; Hall, P.A., Soskice, D., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2001; pp. 21–27. [Google Scholar]

- Kalleberg, A.L. Precarious Lives: Job Insecurity and Well-Being in Rich Democracies; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Korpi, W. Power resources and employer-centered approaches in explanations of welfare states and varieties of capitalism: Protagonists, consenters, and antagonists. World Polit. 2006, 58, 167–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalleberg, A.L.; Nesheim, T.; Olsen, K.M. Is participation good or bad for workers? Effects of autonomy, consultation and teamwork on stress among workers in Norway. Acta Sociol. 2009, 52, 99–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallie, D. Task discretion and job quality. In Employment Regimes and Quality of Work; Gallie, D., Ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 105–136. [Google Scholar]

- Gallie, D. Production Regimes, Employee Job Control and Skill Development. Centre for Learning and Life Chances in Knowledge Economies and Societies, 2011. Available online: http://www.llakes.ac.uk/sites/default/files/31.%20Gallie.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2020).

- ISSP Research Group. International Social Survey Programme: Work Orientations IV—ISSP 2015, ZA6770 Data File Version 2.1.0. GESIS Data Archive: Cologne 2017. Available online: https://doi.org/10.4232/1.12848 (accessed on 24 January 2020).

- Jutz, R.; Scholz, E.; Braun, M.; Hadler, M. The ISSP 2015 Work Orientations IV module. Int. J. Sociol. 2018, 48, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finch, W.H.; Bolin, J.E.; Kelley, K. Multilevel Modeling Using R; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hox, J.J. Multilevel Analysis: Techniques and Applications; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryan, M.L.; Jenkins, S.P. Multilevel modelling of country effects: A cautionary tale. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 2016, 32, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stegmueller, D. How many countries for multilevel modeling? A comparison of frequentist and Bayesian approaches. Am. J. Political Sci. 2013, 57, 748–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enders, C.K.; Tofighi, D. Centering predictor variables in cross-sectional multilevel models: A New Look at an Old Issue. Psychol. Methods 2007, 12, 121–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelman, A. Scaling regression inputs by dividing by two standard deviations. Stat. Med. 2008, 28, 221–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rammstedt, B.; Beierlein, C. Can’t we make it any shorter? The limits of personality assessment and ways to overcome them. J. Individ. Differ. 2014, 35, 212–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallie, D. The quality of working life: Is Scandinavia different? Eur. Sociol. Rev. 2003, 19, 61–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iversen, T.; Soskice, D. An asset theory of social policy preferences. Am. Political Sci. Rev. 2001, 95, 875–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cusack, T.; Iversen, T.; Rehm, P. Risks at work: The demand and supply sides of government redistribution. Oxf. Rev. Econ. Policy 2006, 22, 365–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estevez-Abe, M.; Iversen, T.; Soskice, D. Social protection and the formation of skills: A reinterpretation of the welfare state. In Varieties of Capitalism: The Institutional Foundations of Comparative Advantage; Hall, P.A., Soskice, D., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2001; pp. 145–183. [Google Scholar]

- Culpepper, P.D. Small states and skill specificity. Austria, Switzerland, and interemployer cleavages in coordinated capitalism. Comp. Political Stud. 2007, 40, 611–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurofound. European Working Conditions Survey Integrated Data File, 1991–2015, [Data Collection], 7th ed.; UK Data Service: Colchester, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, T.W.; Davern, M.; Freese, J.; Morgan, S.L. General Social Surveys, 1972–2018, [Machine-Readable Data File]; NORC: Chicago, IL, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- JGSS Research Center Osaka University of Commerce. Japanese General Social Survey 2012 (JGSS 2012), ZA6427 Data File Version 2.0.0; GESIS Data Archive: Cologne, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ESS. ESS Round 5: European Social Survey Round 5 Data, Data File Edition 3.4. NSD—Norwegian Centre for Research Data, Norway—Data Archive and distributor of ESS data for ESS ERIC 2010. Available online: https://doi.org/10.21338/NSD-ESS5-2010 (accessed on 30 January 2020).

- The Role of Unions in the Twenty-First Century: A Report for the Fondazione Rodolfo Debenedetti; Boeri, T., Brugiavini, A., Calmfors, L., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Labour Organization. ILOSTAT Database; International Labour Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Twenge, J.M. A review of the empirical evidence on generational differences in work attitudes. J. Bus. Psychol. 2010, 25, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | Job preference orientations have also been examined according to the terms “job preferences” [1,2], “work orientations” [3,4,5,6] and “work values” [7,8,9]. In this paper, these four terms are used interchangeably, but the term “job preference orientations” is predominantly used. While these different concepts are sometimes associated with slightly different definitions, they all essentially refer to the same phenomena, i.e., to the characteristics of jobs that workers find important and desirable [5,6,8,10]. |

| 2 | Instrumentalism refers to an attitude to work which regards it as a means towards an end, other than the work itself [19]. It usually suggests a primary concern with money and is closely related to extrinsic attachments to work, which is one of its four constitutive components [3,4]. |

| 3 | With cross-sectional data, it is not possible to determine the causal ordering of job preferences and job characteristics. While there is a possibility that the relationship can be affected by self-selection, the study follows previous research and assumes that workers’ ability to choose and shape their jobs is more limited than the effects that jobs have on them [8,13,20]. |

| 4 | These countries were: Austria, Belgium, Croatia, Czechia, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Hungary, Israel, Japan, Latvia, Lithuania, Norway, Poland, Russia, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, the UK and the US. |

| 5 | See Table A1 in the Appendix A. |

| 6 | Cronbach alpha values below the 0.7 cut-off point are frequently reported for scales with only a few items and do not always properly reflect the internal reliability of such short scales. See Rammstedt and Beierlein [43] (p. 214). |

| 7 | The survey also included two items measuring the importance of the social dimension of job preferences (the items “useful to society” and “help others”), which were interpreted in some previous studies as indicators of intrinsic orientations [1,10]. However, if intrinsic orientation is understood in terms of the valuation of continuous personal development [7] and the use of one’s abilities [13], it is clear that the items fail to reflect the individualistic aspect of self-realization implied by the concept. |

| 8 | The measure of relative skill specificity of an occupation is mathematically defined as s/(s + g), where “s” represents a measure of specific skills and “g” is a measure of general skills. Following the approach of Soskice and Iversen [45], Cusack et al. [46] derived the measure from information relating to the level and specialization of skills contained in the ISCO-88 classification of occupations. Firstly, an absolute average skill specificity of an occupation (corresponding to the numerator “s”) is calculated, as a share of unit groups in the higher-level occupational class to which the occupation belongs, and divided by the share of the labor force in that class [46] (p. 371). The value is high when there is a disproportionately high share of unit groups in the occupational class and a low share of the labor force employed in that class. Secondly, in order to transform this absolute measure into a relative index, it is divided by a measure of occupational skill level, a proxy for the total level of skills of an occupation “(s + g)”. ISCO-88 distinguishes four such skill levels, which are defined for all major occupational classes. Values of the resulting relative skill specificity index are high when an individual is in a very specialized occupation, but her level of skills is relatively low. Values are low when the occupation is not particularly specialized, while the level of skills is high [46] (p. 371). |

| 9 | See Table A2 in Appendix A for descriptive statistics of all individual-level variables. |

| 10 | Rather than being two categories of a dichotomous schema, CMEs and LMEs are ideal types constituting a continuum along which all national capitalist systems can be arranged [29]. The skill variation expected by VoC is therefore captured by continuous, and not by categorical, variables. |

| 11 | Alternative indicators of skill diversity, such as vocational training share [47] or tertiary vocational training, [48] were unfortunately available for only a fraction of countries in the ISSP data. |

| 12 | Descriptive statistics for all country-level characteristics can be found in Table A3 in the Appendix A. |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).