Abstract

University–community partnerships have long sought to develop interventions to empower historically marginalized community members. However, there is limited critical attention to tensions faced when community engaged courses support urban planning initiatives in communities of color. This article explores how three Florida State University planning classes sought to engage the predominantly African-American Griffin Heights community in Tallahassee, Florida. Historically, African-American communities have been marginalized from the planning process, undermining community trust and constraining city planning capacity to effectively engage and plan with African-American community members. In this context, there are opportunities for planning departments with relationships in the African-American community to facilitate more extensive community engagement and urban design processes that interface with broader city planning programs. However, mediating relationships between the community and the city within the context of applied planning classes presents unique challenges. Although city planners have increasingly adopted the language of community engagement, many processes remain inflexible, bureaucratic, and under resourced. Reliance on inexperienced students to step in as community bridges may also limit the effectiveness of community engagement. Thus, while community engaged courses create opportunities to facilitate community empowerment, they also at times risk perpetuating the disenfranchisement of African-American community members in city planning processes.

1. Introduction

“You can’t talk about Griffin Heights without talking about Springfield, or Frenchtown because it was one. We were all one. Of course we had our own communities named this, that and the other … but this [Lawrence Gregory Community Center] was the hub here. Where everyone came, where everyone was together, this is where we were, this is where we had the arts and crafts for the whole community.”—Griffin Heights resident

University–community partnerships have long sought to develop interventions to empower historically marginalized community members. This article explores how three Florida State University (FSU) classes in the Department of Urban and Regional Planning (DURP) sought to engage the predominantly African-American Griffin Heights community in urban planning processes in Tallahassee, Florida. Historically, city planners have not engaged African-American community members in Griffin Heights. The legacy of this disregard is a lack of community trust and a diminished city planning capacity to effectively engage African-American community members. In this context, there are opportunities for university planning departments with relationships in the local African-American community to facilitate community engagement and urban design processes that city planners struggle to achieve. Mediating relationships between a historically disenfranchised African-American neighborhood and the city within the context of applied planning classes presents unique challenges. While city planners have increasingly adopted the language of community engagement, city planning continues to be governed by inflexible and bureaucratic processes. The structure of urban planning processes, combined with the often limited availability of resources for community engagement, can inhibit the effectiveness of initiatives to provide voice to those who have been historically excluded. Conversely, students’ inexperience also limits the extent to which applied coursework can effectively engage community members. Thus, while community engaged courses create unique opportunities to facilitate the empowerment of a historically marginalized community, they also are continually challenged by the potential of becoming complicit in perpetuating the disenfranchisement of African-American community members in city planning processes.

We develop this argument through the following five sections. First, we situate our intervention within the literature on university–community partnerships and African-American community activism. Second, the article places discussion of urban planning processes within the context of the community of Griffin Heights and the city of Tallahassee. Third, the article addresses the genesis and development of the partnership between the Division of Neighborhood Affairs, Griffin Heights and FSU DURP faculty and students. We describe how students in applied urban planning graduate courses facilitated Griffin Heights community engagement in the planning process and development of an urban design plan. In the fourth section, we step back to reflect on the opportunities that enabled this university–community partnership, as well as the challenges that inhibited it. We particularly stress issues with inflexible timelines and process adaptability, the importance of community buy-in, difficulties around communication and capacity, and challenges negotiating city bureaucracy and institutional constraints. Finally, we conclude by reiterating our major findings and offering recommendations to foster more empowering university–community partnerships for historically marginalized communities.

2. University–Community Partnerships and African-American Community Activism

Universities have been long recognized as key to the knowledge economy, as institutions that attract and cultivate intellectual talent, facilitate knowledge transfer, and foster economic growth. Recent research has begun to highlight the role of the university within neighborhood and community revitalization [1,2,3]. These dynamics have triggered substantial concern from scholars regarding the potential displacement of historically marginalized communities as neighborhoods reorient towards the university as the anchor institution of the knowledge economy [4,5,6]. However, planning and geography faculty, research clusters, and departments have also sought to leverage the institutional resources and capacity of the university to advance community aims through university–community partnerships [7,8,9,10]. Geography and planning educators have emphasized the educational value of applied learning, helping students not only gain technical skills but also empathy for underprivileged communities and understanding of the importance of effective communication processes [11,12,13].

As highlighted by the scholarship on university–community partnerships, discerning how to appropriately engage a community can be difficult. Even simply determining how a community is organized and who effectively represents the community requires careful attention [14]. As Sarah Lamble stresses, among all the terms used by activists and scholars, “‘community’ is perhaps the most frequently used, least explicitly defined, and most elastic in its meaning,” and thus efforts “to delineate its boundaries invariably result in contentious debate” [15] (p. 103). Failed attempts at community engagement often result from insufficient attention to community dynamics and over-simplified assumptions about homogeneous community norms [16]. Critical scholars have further challenged the pervasive rhetoric of community empowerment through university partnerships, asking if university–community partnerships are really helping impoverished communities, or rather reproducing expert authority and providing educational opportunities for relatively elite students to hone their skills in practice with underserved populations [17,18,19]. Scholarship on university–community partnerships has highlighted enduring issues related to differences between how planning professionals and historically marginalized communities conduct meetings, understand community issues, approach leadership, and make decisions [20,21]. Moreover, as the funding allotted for university–community partnerships remains sparse, there is also often a disjuncture between project aspirations and realizable outcomes [22].

Studies of African-American activism highlight the chasm that often exists between how city officials and community organizers understand the geography of African-American neighborhoods. George Lipsitz explicitly contrasts what he terms the white and black spatial imaginaries, while acknowledging some black people adhere to the white spatial imaginary (and not all white people do) [23]. He argues the white spatial imaginary is based on decades of normalized practices that aim “to hoard amenities and resources, to exclude allegedly undesirable populations, and to seek to maximize their own property values in competition with other communities” [23] (p. 28). He argues that the white spatial imaginary still underpins urban policy environments. In contrast, African-American spatial imaginaries have typically had limited influence over formal policy and legislative environments. Nevertheless, African-American communities continue to organize in venues outside formal political processes, such as churches and neighborhood associations [24,25]. In such spaces, African-American community members share their experiences, grievances, and aspirations, circulating distinct visions for the neighborhoods through churches and other spaces of community congregation. Characterizing these visions as distinct spatial imaginaries, Lipsitz suggests African-American communities typically approach place-making not through the lens of personal accumulation and exclusion, but rather “as a public responsibility for which all must take stewardship” [23] (p. 69).

Thus, community planning processes that aim to engage historically marginalized African-American communities need to attend to the distinct visions that these communities articulate for meeting their community needs and desires, recognizing that there is not a single African-American community engagement process or spatial imaginary. Engagement processes must be sensitive to local context, including the different spaces in which neighborhood residents organize, the different forms of knowledge and communication that are privileged in these spaces, the timelines appropriate to the circumstances and capacity of the local community, and the particular priorities and needs of that neighborhood. Planners and community organizers need to be attentive to distinct neighborhood orientations that arise from their particular collective memories, oral histories, community practices, and modes of sharing space, as well as particular encounters with law and policy, histories of dispossession, and long struggles for freedom and self-determination. All these elements of community history and bonds create durable and distinct community frames of reference. Translating these frames of reference to city officials is vital to protecting African-American community concerns and supporting the flourishing of these communities. However, it is also important to recognize that the established processes of city governance may not facilitate or resonate with the knowledge and organizing practices of an African-American community.

3. Case Study Methodology and Local Planning Context

As there is no universal template for how community engagement or planning the built environment should unfold in African-American communities, it is necessary to position interventions within the context of the community and its relation to urban planning processes. We employ a case study methodology to situate these dynamics within the particular context of the Griffin Heights community. In this section, after outlining our case study methodology, we explicitly ground analysis with respect to the Griffin Heights neighborhood and the city of Tallahassee. We then situate our university–community partnership specifically in relation to the City of Tallahassee Neighborhood First planning process that created the opportunity for our applied graduate classes to facilitate the involvement of the Griffin Heights community within a city planning process.

3.1. Case Study Methodology

Scholars use the case study approach to examine a particular instance of a phenomenon in order to explore it in the depth of its surrounding context [26,27]. As Bent Flyvbjerg describes, there is an “irreducible quality of good case study narratives” [28] (p. 237). The methodology of the case study embraces the complexities and contradictions of social and political life and is an approach that helps examine contexts that “may be difficult or impossible to summarize into neat scientific formulae, general propositions, and theories” [28] (p. 237). Case studies are particularly valuable to compile nuanced and thick analysis of the interrelationships among specific places, people, and processes [29]. Thus, the case study approach enabled us to interrogate how the implementation of standardized planning processes created tensions with the particular context of an impoverished African-American community.

Simultaneously, the case study approach enables us to think through the tensions involved in community-based classes that attempt to bridge city planning with historically marginalized communities as a pedagogic opportunity. The nuanced and holistic interpretative framing of case study research has been a particularly valuable framework to unpack the tensions involved in community-based classes engaging with marginalized communities. For instance, reflecting on a studio-based class project facilitated with residents of two informal settlements located in Cape Town, Tanja Winkler highlights that under certain circumstances class engagements with economically stressed communities do not benefit those communities [30]. As Libby Porter describes, analysis of community-based planning pedagogy demonstrates “just how fragile, difficult and complex partnerships can be” [31] (p. 413). Conversely, successful service learning projects—that serve both pedagogic and community empowerment functions—rely upon careful attention to context, often allowing the messiness and discomfort involved in community engagement unsettle the standard privileged frames within planning processes and education [31,32]. The contextual nuance of case study methodology is thus invaluable to understanding both instances of success and failure of community-based pedagogies.

Our particular case study is built upon nine months of involvement in formal and informal planning and community engagement processes in Tallahassee, including three graduate-level urban planning classes over two semesters. The first course, Neighborhood Planning, situates community planning in a historical context that examines how neighborhood planning works in practice and highlights the challenges of overcoming existing racial and spatial inequality and advancing racial equity and social justice. This class typically works with community stakeholders to develop quality of life plans utilizing the LISC New Communities Program as a tool for improving the quality of life for residents in communities of color. The second course, Community Involvement and Public Participation, is a process-based course focused on assessing the theories, concepts, and cases related to public participation in the planning arena. The course uses Sherry Arnstein’s ladder of participation as an anchor to guide students through the various positions planners can take when engaging with the public [33]. The course’s orientation looks up to the higher rungs of the ladder of collaboration and empowerment as an ideal to aspire to when pursuing a socially just and equitable long-term planning process with communities. The last course, Urban Design, focuses on understanding the principles, practice, and implementation of urban design in U.S. metropolitan areas. This course pays close attention to the challenges involved in designing just cities that plan for diversity, foster equity in design practices, and engage with both public and nonprofit actors to develop and implement urban design plans.

Through the three courses, students engaged the community, collected information on the community and planning process, and developed a design plan for Griffin Heights. Students in courses compiled archival documents, collected oral histories from residents, and conducted a community survey. They also attended regular community planning meetings over the semester as participant observers. As process facilitators, faculty and students also maintained ongoing communication with community stakeholders and City officials throughout the planning process. This research was conducted under the Institutional Review Board at Florida State University (HSC No. 2019-26947).

3.2. Tallahassee and Griffin Heights

Tallahassee is a mid-sized city, with a population of approximately 194,500, on the Florida Panhandle in the northwest corner of the state. Located along the southern edge of the Black Belt, or historic plantation economy, the percentage of the population that is African-American in the city (34.8%) is more than twice the state average (16.0%). The city also has a significantly smaller Hispanic population (6.9%) than average in the state (22.5%). Tallahassee is the State Capitol and hosts three prominent state educational institutions: Florida State University (FSU—a predominately white institution), Florida A&M University (FAMU—a historically black college/university), and Tallahassee Community College (TCC). As a college town, Tallahassee has a very young population, with a median age of 27.2 years, significantly beneath the national figure of 38.2 years. Moreover, the owner-occupied housing units rate in Tallahassee (39.9%) is well below the national average (63.8%).

Tallahassee has one of the highest crime rates in the US. Florida Department of Law Enforcement data show Leon County, where Tallahassee is situated, possesses the third highest crime rate in Florida. Moreover, FBI reported crime data indicate that the city has one of the highest violent crime rates in the country. In a college town such as Tallahassee, these figures are inflated as students contribute to offenses but are not included in county population statistics. Nevertheless, the high crime rate is a major local political and policing concern. The city police have adopted new data analytics so it can target resources to higher crime areas. This has expanded police surveillance of impoverished neighborhoods where crime rates are higher. However, concern with crime has also spurred the city to target planning resources to high crime areas as a crime prevention initiative.

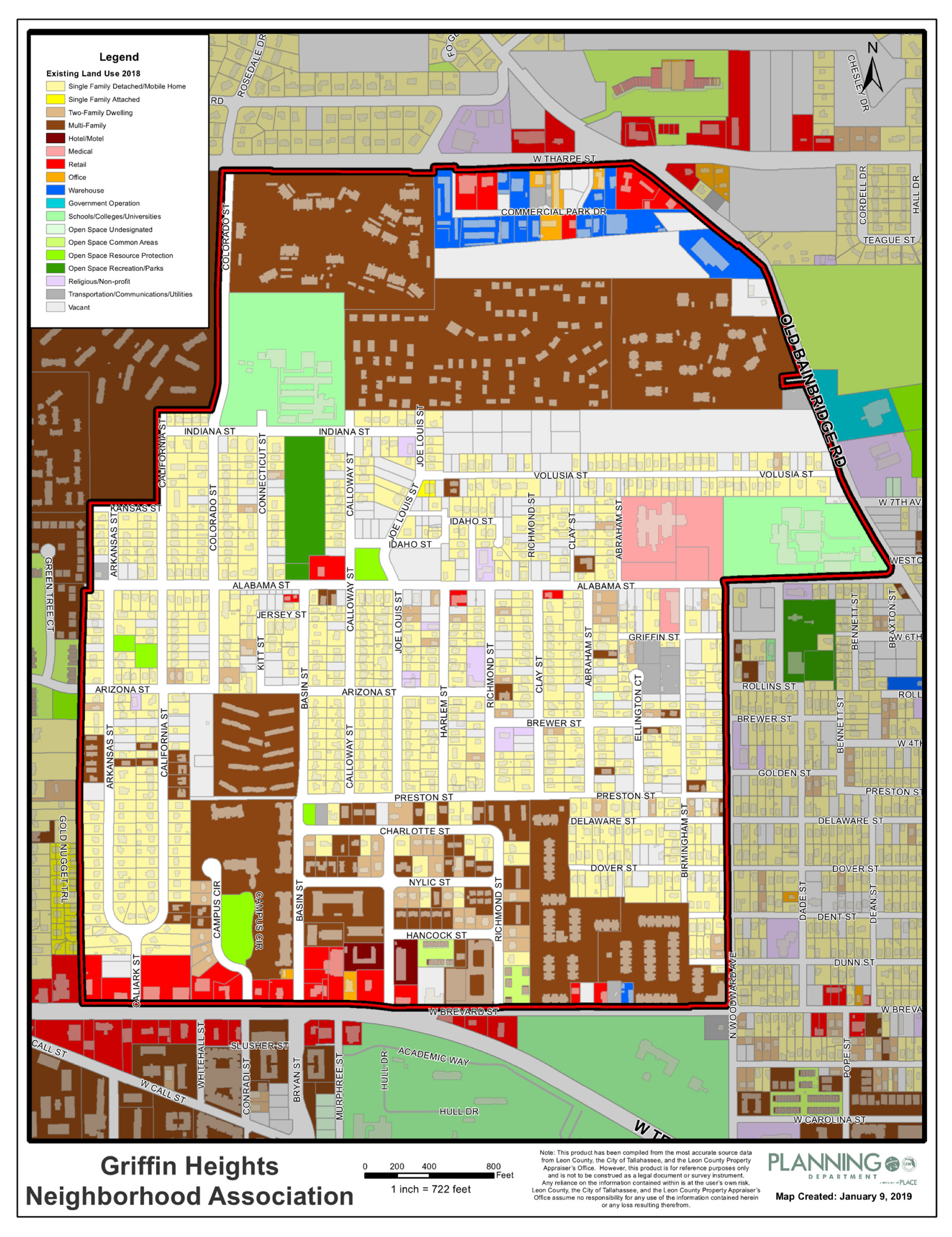

As a city, Tallahassee continues to be racially segregated, with the African-American population concentrating in particular neighborhoods. Historically, the African-American community in Tallahassee clustered into two enclaves, one south of the Seaboard Railroad Line around FAMU and a second immediately north of FSU. While the neighborhoods adjacent to FAMU include the university faculty and middle-class residents, the neighborhoods north of FSU exhibit particularly high levels of poverty. Although FSU officially racially integrated in 1962, it remains predominantly white and there are longstanding tensions between it and the historical African-American communities that abut it [34,35]. The 32304 zip code, which includes the predominantly African-American neighborhoods north of the FSU campus, is the poorest zip code in Florida and an area with elevated crime rates. This is where Griffin Heights is located (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Griffin Heights Location in Relation to FSU and Florida Capital (Source: City of Tallahassee).

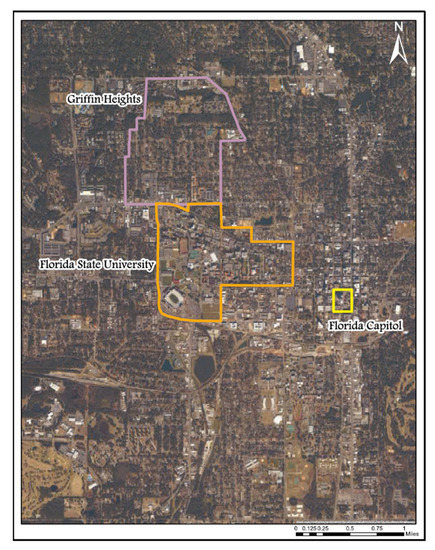

While economic and crime statistics portray Griffin Heights as an undesirable community, it is a community with a long history and strong identity. In many US cities, the African-American population concentrated in the older urban core as white residents relocated to the suburbs perceived to be more desirable post-WWII. However, Griffin Heights and the adjacent Frenchtown neighborhood are not products of white flight to the suburbs. They are among the oldest African-American neighborhoods in the state [36]. The historic foundation for the Griffin Heights community was the Griffin Normal and Industrial Institute for Negros, which opened on the corner of Abraham and Alabama Street in 1908. Primitive Baptist Church congregations played a vital role in creating Griffin Institute, which was named after Reverend Henry Griffin, the first Primitive Baptist pastor in Florida. As Griffin Heights expanded, churches and schools continued to play a vital role in the neighborhood, serving as spaces for community gathering, organization, and cohesion (Figure 2). As Eric Lincoln and Lawrence Mamiya note in their classic study, The Black Church in the African American Experience, churches form the core of urban African-American community and have “multifarious roles in moral nurture, politics, education, economics, and black culture in general” (1990, p. 122).

Figure 2.

Historical photographs of teachers and students at Lincoln High School (Source: Riley Archives).

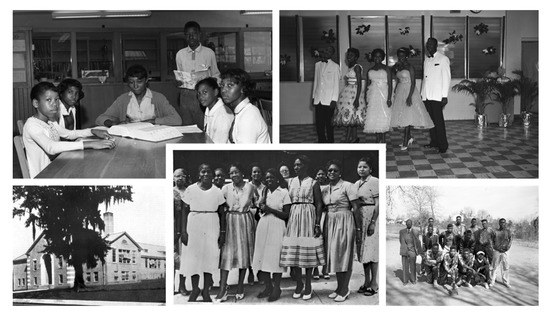

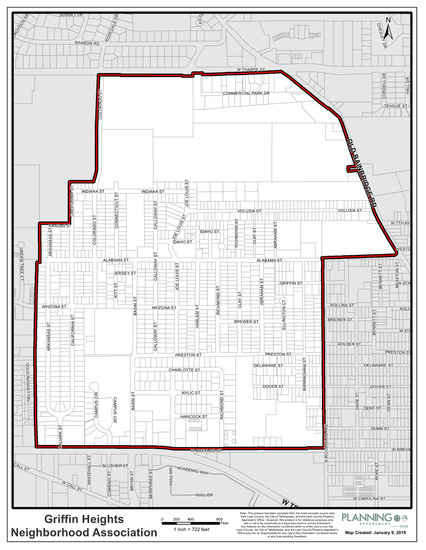

As a community, Griffin Heights developed distinct characteristics from other adjacent African-American neighborhoods, as well as the broader city of Tallahassee. The extent of the Griffin Heights remains ambiguous, with different entities and agencies using different boundaries. Because of the processes of urban change occurring around Griffin Heights, particularly in the area immediately north of the university, different boundaries create entirely different demographic profiles of the community. Here we will use two sets of boundaries to characterize the neighborhood. The first set of boundaries were defined by residents and historical Sanborn maps (Figure 3). Focusing on this delimited core area, where over 90% of the residents remain African-American, enables us to articulate the distinct characteristics of the historic Griffin Heights community. Conversely, surveying the broader neighborhood, as we do below, highlights the breadth of opportunities for local neighborhood development, the significant available land that could be used to improve neighborhood services and amenities, as well as how university-oriented redevelopment threatens to displace this historic African-American community.

Figure 3.

Griffin Heights Original Neighborhood Boundaries (Source: City of Tallahassee).

There are 311 households and 646 residents in the area that residents depict as the core of the Griffin Heights community. Unlike many adjacent neighborhoods, where the overwhelming majority of residents are renters, the core of Griffin Heights has a relatively even distribution of owner-occupied (146) and rental units (165). The core of the community is an older working-class neighborhood, with a median house value ($115,789) significantly lower than that of the city ($185,100), and a median age (48.4 years) almost double that of the city (27.2 years).

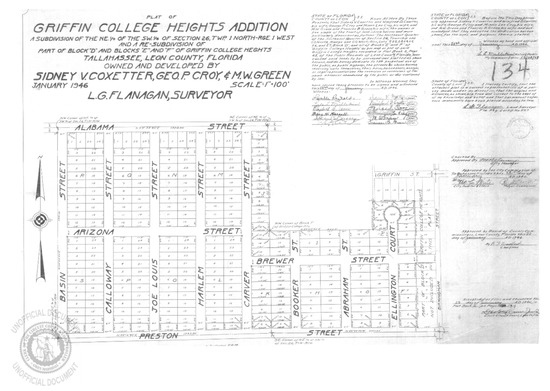

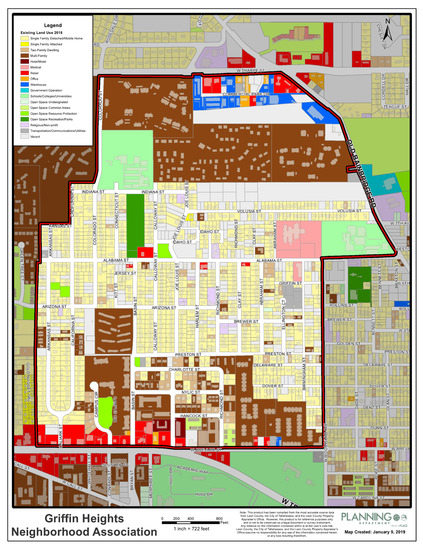

With an aging population, residents of Griffin Heights have expressed fears about the potential loss of the community, particularly from displacement by student housing developments. Their worries stem from what they have observed in nearby neighborhoods, particularly Frenchtown, where housing developers have introduced luxury student apartments to a historically marginalized African-American neighborhood [37]. There are already significant student housing developments bordering Griffin Heights. The expanded boundaries used by the Griffin Heights Neighborhood Association (GHNA) showcase how these developments change the character of the neighborhood (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Griffin Heights Neighborhood Boundaries (Source: City of Tallahassee).

While older African-American households constituted the overwhelming majority of the core of the Griffin Heights neighborhood, expanding the boundaries radically alters the neighborhood demographics. The broader area has 5478 residents, with a median age of 23.8 years. While the area remains predominantly African-American (67.8% of residents), the student housing also introduces a significant white population to the neighborhood (25.1%). Moreover, of the 3048 housing units within the expanded boundaries, only 14.3% were owner occupied and 71.2% were renter occupied in 2018. In recent years, the number of renters in the area has been increasing and the number of owner occupied homes has been falling. In 2010, there were 1949 rental units in the area; by 2018, this figure had grown to 2182. Conversely, there were 520 owner-occupied homes in 2010, but only 436 remained in 2018. The data indicate that homeownership in the neighborhood is becoming increasingly difficult to attain.

However, there is also significant potential to reinforce and revitalize the existing community in Griffin Heights. Within the expanded boundaries used by the GHNA, there are a total of 172 vacant lots for a combined 52 acres of vacant land throughout the neighborhood, which offer significant land for potential redevelopment (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Land Use within Griffin Heights Neighborhood Association Boundaries (Source: City of Tallahassee).

There are concentrations of vacant lots in the center and east side of the neighborhood, as well as two large swaths of vacant land on the north side of the neighborhood that remain inaccessible with the current infrastructure. In addition to the vacant lots, there are 46 city and county owned parcels and 41 parcels that have poor housing conditions. Thus, overall, there are 253 parcels, 36% of the existing lots in the area, composing 74 acres that could be available for redevelopment. Many of these parcels are currently poorly kept, often attracting dumping and contributing to crime; however, these spaces present opportunities where new neighborhood amenities and services could be built. Although vacant lots are often seen as a sign of disinvestment in a community, they could be remade to embody the vision of Griffin Height’s residents for their neighborhood. Griffin Heights has been designated an Opportunity Zone, so it is especially important to promote social impact investments that can mitigate potential displacement pressures. However, for this to happen, it is imperative that neighborhood planning processes engage community residents and city planners adopt policies consistent with current residents’ wants and needs in order to ensure development is equitable and protects the historic African-American community.

3.3. Neighborhood First Planning Process

Neighborhood First is a multi-step planning process designed to assist neighborhoods that are participating in the Neighborhood Public Safety Initiative (NPSI) with developing an action plan to address community priorities. NPSI addresses public safety through the following principles: Crime Prevention and Education, Community Beautification, and Community Empowerment and Volunteerism. NPSI is a collaborative effort of the local Public Safety Collective—current members include the Tallahassee Police Department, the Leon County Sheriff’s Office, FSU Police Department, FAMU Police Department, TCC Police Department, Capitol Police, the State Attorney’s Office, Big Bend Crime Stoppers, and the Tallahassee Fire Department. Neighborhood First Initiative has now grown into a citywide planning process to identify, assist, and cultivate regrowth in some of Tallahassee’s oldest and most cherished neighborhoods. The Neighborhood First planning process is deeply rooted in public participation and follows a community-driven approach. In particular, the Neighborhood First Initiative is defined by the City of Tallahassee as:

“A strategic, neighborhood-lead [sic] planning initiative staffed by Neighborhood Affairs and supported by the Tallahassee-Leon County Planning Department and other city departments.”

The Neighborhood First planning process engages the residents of targeted neighborhoods, but also involves partners from across Tallahassee in developing the plans. Committees are formed from the most active and engaged citizens to lead the discussion in the identified priority areas. The centerpiece of the planning process is the Community Action Team (CAT). The CAT serves as a leadership team/advisory group to the planning process; provides updates to the neighborhood association and feedback to committees.

The Division of Neighborhood Affairs served as the main administrator for the Neighborhood First planning process and connector of the different stakeholders involved. Planners in the Division of Neighborhood Affairs continuously identified and recruited key partners in the community including the GHNA, FSU DURP, City of Tallahassee representatives, and churches. They provided logistical support for scheduling and hosting monthly meetings in neutral community spaces, printing communication materials, and cultivating relationships with community leaders to promote greater ongoing participation. Much energy was spent recruiting participants for the CAT and ensuring that the group was representative of as many voices in the community as possible. The Division of Neighborhood Affairs also coordinated and facilitated monthly subcommittee meetings focused on specific issue areas. During these meetings, staff presented information via PowerPoint from previous meetings or new data collected from the process, and then worked with CATs to narrow down and build consensus on community priorities, goals, and strategies. When there was overlap of issues, new concerns, and items which were beyond the scope of the process, planners in the Division of Neighborhood Affairs sought to serve as a sounding board to give residents the space to voice and work through their concerns. They tried to find opportunities to clarify, reframe, synergize, and consolidate issues into more manageable priorities and tasks and also served as a router of information where they were able to clarify questions and spheres of responsibilities for different agencies. The intention of these facilitated meetings was to develop clear outcomes and strategic action items that can be taken in the near or long term to achieve these outcomes.

To implement the Neighborhood First planning process in Griffin Heights, the City of Tallahassee Division of Neighborhood Affairs worked in collaboration with the FSU DURP, and the GHNA. Neighborhood First encompasses collaborative working relationships between residents and other stakeholders both within and outside Griffin Heights. DURPs participation included integrating the Neighborhood First planning process into a series of three courses pro bono from August 2018 to May 2019. Each of the three courses—Neighborhood Planning, Community Involvement and Participation, and Urban Design—integrated applied practice-oriented projects and community engagement. The courses were designed to interlink, collectively oriented to the goals of building university–community partnerships, supporting the Griffin Heights community adjacent to FSU, and providing students with service learning opportunities. Neighborhood Planning students laid the initial groundwork for partnership with Griffin Heights through more informal engagement practices; Community Involvement and Participation students supported formal outreach efforts; and Urban Design students collected data through community-based practices to support the development of built environment design solutions. All together, these three courses supported the City of Tallahassee’s efforts in engaging the community and developing a Neighborhood First Plan for Griffin Heights.

4. The City–University–Community Partnership in Griffin Heights

FSU DURP students and City staff began this process by working with the GHNA, who was the primary stakeholder that acted as the gatekeeper for information and access to the residents. This process began informally, as Neighborhood Planning students in Fall 2018 started to attend the monthly GHNA meetings to gather a sense of the context of local community planning. These initial connections were followed up by interviews with key community partners. This process facilitated building relationships with residents and understanding the Griffin Heights neighborhood. Students collected demographic data, mapped existing neighborhood conditions, assessed community assets and needs, and identified priority areas of improvement, case studies, and preliminary ideas for Griffin Heights. The preliminary process included a focus on four core areas: Community Beautification, Neighborhood Infrastructure, Neighborhood Safety and Crime Prevention, and Resident Empowerment and Community Engagement. These four areas serve as the backbone for neighborhood-wide initiatives and cater to residents’ needs and their vision to enhance the neighborhood’s resources and quality of life. Students presented Neighborhood Assessments at the end of the Fall 2018 term to the City of Tallahassee.

This process continued through Spring 2019 with Community Involvement and Participation and Urban Design students working within the formal Neighborhood First planning process. A kick-off meeting was held at Griffin Chapel in January 2019 to inform residents about the Neighborhood First planning process, share initial ideas from the Neighborhood Assessment, and brainstorm about the key issue areas Griffin Heights residents wanted to have addressed. The brainstorming session was facilitated by an FSU DURP faculty member, who has significant experience working in Tallahassee communities as a meeting facilitator. Community members were guided through a series of prioritization exercises to identify the major areas of concern facing the community and the top needs. Stakeholders were given a commitment and interest form on which they could identify their major areas of interest and possible level of participation in the process.

To better respond to the neighborhoods priorities, in addition to receiving feedback from the GHNA, after the kick off meeting the City of Tallahassee Division of Neighborhood Affairs started to identify stakeholders from commitment forms and conducted further recruitment to create the CAT. The CAT had two subcomponents—the People and Places committees and the GHNA. The two committees served as broader outreach arms comprised of three to five residents. The People Committee focused on community beautification and neighborhood infrastructure issue areas, while the Places Committee targeted public safety, resident empowerment, and community engagement. The GHNA held meetings on a monthly basis to develop goals, strategies, and action steps for the Neighborhood First Plan.

4.1. Role of Community Participation and Involvement Course

Outreach Structure. After the meeting, students were organized into consulting groups defined by specific roles to support the Neighborhood First planning process. During the first phase of the project, one group was tasked with developing a Facebook page to serve as the main social media platform to advertise upcoming meetings and events, as well as disseminate information. A second group was tasked with attending committee meetings and supporting the FSU DURP faculty with facilitation, data collection and synthesis. A third group of students spent time generating ideas to engage the community including compiling oral histories to create a story box and holding a charrette style youth event. Students also spent time identifying community stakeholders outside of the Neighborhood Association who could serve as facilitators to the project, such as: the Community Center; schools; businesses; community residents in apartment complexes; the DREAM Center led by a church pastor; and TEMPO, a city agency responsible for transitioning young adults to GED completion or work programs.

Community Survey. The second phase of the process consisted of distribution of a community survey. This required significant manpower to disseminate to the community. The community survey was designed by the Urban Design class, then pilot tested with community leaders and students in the Community Participation class. Once finalized, the survey was printed as well as uploaded to the Facebook page. Students spent several class sessions discussing the challenges of survey design and dissemination in order to prepare for distributing the community survey. Community Participation student teams were positioned over two weeks at key locations in the community including the Elementary and Middle Schools, the Griffin Heights Apartments, and the Lawrence Gregory Community Center. Door-to-door surveys were also distributed with the assistance of the Urban Design students. The most effective method of disseminating the survey was through attending church services and asking congregants to fill out the survey during the service or as they left the church. Having the pastors agree to allow students to attend and conduct the survey was an important strategy. Pastors were also key in letting their congregations know that the Neighborhood First planning process was happening in the community and why it was important for the residents to participate and share their thoughts. The survey garnered 220 responses that were manually inserted into Survey Monkey. This response rate resulted in twice as many surveys collected as the prior Neighborhood First planning process in the Bond neighborhood, largely as a consequence of students’ capacity to deliver the survey widely.

While the survey was conducted, the Division of Neighborhood Affairs staff prepared to set up and facilitate the CAT as well as the People and Places committee meetings. The People and Places meetings were intended to have community members focus on the pertinent issues, further prioritizing needs and brainstorming and coming to consensus on the solutions. The Division of Neighborhood Affairs staff sought the help of church leaders to recruit participants and also to host these meetings in their respective meeting rooms. Students attended these sub-meetings as recorders and support for the primary FSU DURP faculty facilitator, collecting feedback responses on post-its, taking meeting minutes, etc. The results from the committee meetings were then presented at the larger CAT meetings held in the Griffin Chapel center and the Lawrence-Gregory Community Center. The survey results were also presented at the CAT meetings and residents were given an opportunity to ask students questions, as well as provide feedback and insights into the results.

Youth Event. The final phase included a component aimed at engaging the younger demographics in Griffin Heights. This charrette style event was developed with the purpose of engaging young people in the Griffin Heights community to share their opinions and ideas on the future of the neighborhood. Since surveys were disseminated to the heads of households, there was gap in the perspectives of those who were 18 and younger. Their perceptions of what neighborhood amenities are needed in the community could differ from those of adults and elders. The youth event was held at the Tallahassee Urban League Office building in Frenchtown. Graduate students developed activities targeted to youth aged 4–14, including an education station which oriented youth visitors to the basics of neighborhood planning concepts, a general overview of the existing conditions, a participatory mapping exercise which asked youth to identify assets and needs in the community using red and green stickers, and finally designs for vacant lots with a visual preference survey to identify what designs youth preferred. At the end of the session, participants were asked to reflect on learning lessons, provide feedback on ideas for improvements to the session, and help identify youth leaders who could serve as liaisons in the Neighborhood Association and in the Neighborhood First process.

4.2. Role of Urban Design Course

Class Organization. Students were organized into three functional teams at the beginning of the semester to replicate a consulting firm that was commissioned to develop an urban design plan. Group 1 was tasked with refining the neighborhood assessment completed in the Neighborhood Planning class to include a windshield survey and built environment conditions. Group 2 focused on community engagement and attended CAT meetings and developed and distributed the community survey. Group 3 worked on conducting oral histories and collecting archival documents, photographs, and maps to create a historical narrative and timeline to be shared with residents. At the midterm, groups transitioned to focus on developing urban design solutions derived from the community-based data collection process. The final included providing a presentation and draft urban design plan to the City of Tallahassee and CAT.

Oral histories. Students worked in conjunction with the City of Tallahassee’s Division of Neighborhood Affairs to compile Griffin Heights’ history and share it with the community. Students engaged former and current residents to share their stories through oral histories about living in the neighborhood, creating a picture of its changes over the decades. Primarily, interviews and conversations with community members provided the richest accounts of Griffin Height’s development and community assets. Staff of the City of Tallahassee, the Department of State, and the Riley Museum and Archives also provided access to historical data about significant people and events that influenced the Griffin Heights Community. The oral histories captured the major dynamics and foundations that shaped the neighborhood beginning in the early 1900s and aimed to showcase Griffin Heights’ beginnings in order to orient planning with a sense of community history, ensuring that the trajectory of development respects the community’s character and rich history as one of the state’s oldest African-American neighborhoods. Compiling the neighborhood’s history facilitated a comprehensive reservoir of cultural resources pertaining to the neighborhood, its residents, and surrounding communities. With community partners’ constant participation and feedback over four months, the working group was able to identify community leaders and key residents who were local knowledge holders and experts in the community history. By collecting these oral histories, the class and the design process could account for the strong historic African-American community connections to the Griffin Heights neighborhood. However, the class’ ability to construct the early neighborhood history was limited—those events occurred before the living memory of the oldest neighborhood residents, and there are few written records of African-American urban history in Tallahassee beyond citywide neighborhood maps. Likewise, the neighborhood’s social and historical boundaries have transformed over the decades. According to residents’ testimonies, current boundaries are much larger than they were in the 1940s and 1950s. Thus, more extensive research on neighboring communities could assist in developing a holistic picture of Griffin Heights’ historical development. Moving forward, collection of the historical data should continue through the development of community relationships and storytelling—one of the community’s strongest forms of historical preservation.

Community Based Data Collection. Students utilized community-based data collection processes to understand both community assets and needs of the Griffin Heights neighborhood to later develop design solutions. To understand Griffin Heights, Urban Design students built upon the work of the Neighborhood Planning class and refined the boundaries of Griffin Heights to align with the GHNA service area. Although residents shared that the core of Griffin Heights was a much smaller area, for the purposes of creating a more holistic approach to neighborhood revitalization, the larger boundaries were used. Using a combination of ArcGIS mapping, U.S. Census data, and windshield surveys, students created a neighborhood profile with demographic information and developed existing conditions maps documenting zoning, land use, assets, land ownership, building conditions, and potential soft sites for future development opportunities.

Next, the class created the Griffin Heights community survey based on the input residents provided during neighborhood association meetings along with community-wide input. Collectively, the survey posed questions encompassing the following priority areas and concerns: (1) neighborhood safety and crime prevention; (2) community beautification; (3) neighborhood infrastructure; and (4) resident empowerment and community engagement. The survey catered not only to Griffin Heights residents, but also to those who work, visit, and play within the community. The survey asked residents to prioritize potential implementation strategies within the main four sections. The survey showcased ideas for sidewalk implementation, safety through street lighting and community block groups, engagement activities, and vacant lot redevelopments that would resonate with the historic character of the neighborhood rather than spur displacement. It also provided an opportunity for respondents to propose new ideas. As a final component, the survey invited respondents to get involved in the planning process, providing respondents with the option to share their contact information. This information helped identify potential individuals to participate in focus groups and community committees.

Students analyzed survey data and found that community members greatly valued the neighborhood’s strong sense of community, with stable, long-term, connections and bonds which provide residents with both support and collective identity. People liked to belong to a community where they had long-standing relationships with their neighbors. Overall, the consensus view in Griffin Heights pointed to three primary areas of central concern: physical and mental health, the youth, and safety. Participants believed that mobile health units, provision of safe spaces for counseling, and health workshops would benefit the community. They also expressed an interest in organizing a farmers market. Additionally, a large majority of the responses showed the community would like to see more youth involvement and youth-centered services. Examples of youth engagement strategies included forming a youth council as a part of the GHNA, as well as offering after-school programs and youth employment opportunities. Finally, community members felt specific design components would improve both neighborhood accessibility and safety. Residents wanted to see an improved network of sidewalks along with improved street lighting throughout the neighborhood.

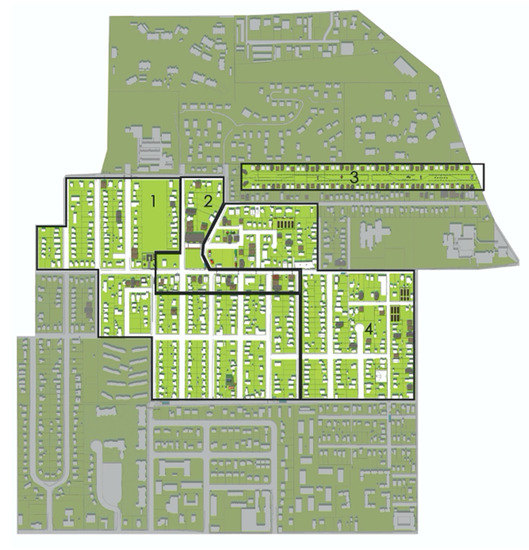

Design and Vision Concepts. In correspondence with the four focus areas, Urban Design students largely responded to the Places committee feedback on neighborhood infrastructure and community beautification issue areas. The design team identified eleven improvement opportunities within four districts to implement infrastructure improvements and enhance community assets. The improvement opportunities and districts include: urban infill districts, the activation of vacant lots, creation of temporary spaces, development of pocket neighborhoods, an Eco-District, an affordable housing district, the creation of a mixed-use Main Street Corridor, the implementation of a heritage trail to showcase neighborhood history, streetscape improvements, and bicycle infrastructure (Figure 6). Across the four districts, we proposed a total of 162 units of single family and live–work housing; 2806 square feet of retail; and 1.3 acres of community parks and gardens.

Figure 6.

Urban design master plan.

We proposed two urban infill districts located in the middle of the community. These districts seek to revitalize the neighborhood by including communal spaces in vacant lots tucked between existing and proposed housing. Neighborhood amenities in this district serve to increase informal resident congregation through the inclusion of a basketball court, pop up space for community activities and two community gardens. These improvements will maintain the character of the district while giving residents access to recreational activities that promote healthy and sustainable lifestyles (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Urban infill development recreation: before (a); and after (b).

The proposed Main Street district runs along Alabama street bounded by Colorado Street to the West and Clay Street to the East. There are currently about 20 vacant parcels along Alabama street, which already functions as the neighborhood’s main thoroughfare. Currently, there is limited commercial development on the street; however, a revitalized main street corridor could be developed through lean urbanism (small-scale, incremental) and placemaking practices. This district can serve as a beacon to revitalize the neighborhood’s lost and much needed commercial activity through the inclusion of live–work communities and commercial infrastructure (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Main street café: before: (a); and after: (b).

Additionally, a pop up space for activities from health fairs to food truck cook outs will promote neighborhood economic activity (Figure 9). The area will be served by a newly designated central parking lot to reduce the instances of on street parking. Finally, bio swales, lighting and overall streetscape improvements will promote a sense of safety and will allow residents to support their local businesses during the day and night.

Figure 9.

Pop up food trucks: before: (a); and after: (b).

Eco-District is bounded by California and Basin St to the west, Indiana St to the north, Joe Louis St to the east, and Preston St to the south. This district will provide residents access to health and wellness facilities through the activation of vacant lots. The district will include ecologically sustainable amenities, serving as catalytic projects such as a wellness center and an urban food forest as well as other passive green spaces dispersed throughout the district (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Eco district community garden: before (a); and after (b).

The Affordable Housing district is located on a large plot of undeveloped land in the northeast corner of the Griffin Heights. This district will include newly developed affordable single family housing looking onto a chain of parks (Figure 11). These parks will stimulate residents’ interest in nature, community gatherings, outdoor performances, and promote walkability while activating an unutilized space in the best interest of Griffin Heights residents. A revitalized streetscape would accompany the improvements in land use and housing stock (Figure 12).

Figure 11.

Affordable housing: before (a); and after (b).

Figure 12.

Streetscape improvements: before (a); and after (b).

For the execution of these ideas, an essential component of the design process was fhe development of implementation strategies that also serve to identify funding sources. However, implementation strategies are ever evolving, subject to ongoing change as planning agencies continue to learn from neighborhood residents and refine community goals through an equitable, resident-led planning process. Throughout all planning stages, it is paramount to maintain equitable practices that keep residents and their vision at the forefront to ensure the outcomes of the urban design plan are indicative of their needs and demands.

5. Reflections on Lessons Learned

The rationale for public participation as well as the challenges planners face through engagement are well documented [38,39,40,41]. Planners can fall into a technocratic trap of prescribing what is best for the community and imposing strategies or designs from models, GIS, and data analysis without seeking public input or considering the specific needs of the community they serve [42]. A common pitfall is that community input is regarded as an afterthought or a means to end, rather than a key component in the process. This can lead to prescriptive engagement efforts, which lack substance and produce design suggestions that are disregarded in the final decisions [43].

Genuine and sustained engagement by the public is critical in order to promote more equitable planning decisions and outcomes, particularly in communities of color. With increased institutional constraints on budgets and staff, finding opportunities to engage with communities of color requires ingenuity, adaptability, and realistic expectations for what can be achieved. Using community engaged field courses to support the engagement processes gives agency to communities to voice their concerns and visions, and an opportunity to advance their aspirations. However, community engaged courses that participate in city-led interventions must strategically navigate the institutional constraints that can perpetuate the status quo as students and faculty work within the existing systems of structural racism and white supremacy.

The purpose of public participation may be acceptable to students, but the value they place and the skillsets used when engaging with the public vary widely. By exposing students to material that challenges their preconceived notions of “community” and their role as a professional when working with the community, students have an opportunity to start the hard work of self-reflection to begin to break down their biases so they may better serve community residents. These courses teach students how to work with communities of color, while examining why participation is necessary, the barriers to participation and the components of a robust participatory process, and how to take information and data collected to produce plans that are community centered.

5.1. Inflexible Timelines and Adaptability

Designing and implementing a community engagement process as applied course projects present several well-known challenges due to the unpredictable nature of doing community work on a compressed timeline within a semester. These time constraints are further complicated when projects are conducted in combination with city authorities governed by their own timelines. Throughout the semester, the Division of Neighborhood Affairs modified timelines, pausing and redirecting activities to meet their predetermined objectives for the process. Needless to say, these modifications impacted time-constrained coursework. Adapting to changes in the semester, with established course plans and learning outcomes, was difficult. There were times when students had to move forward rather than continue an iterative process of engagement in order to meet established course learning objectives.

However, students learned other lessons as they sought to deal with the fluid and shifting demands of city planning work. They witnessed the difficulties of managing timelines for public participation and plan making processes. Moreover, the time intensive nature of the work required to sustain a community engaged effort could only be achieved by having 40 students across three classes working on the project. With limited staff and resources dedicated to other projects, the courses were able to increase the breadth of the historic and neighborhood context that informs city decision-making beyond what Division of Neighborhood Affairs staff could accomplish. The increased capacity provided by the students enabled the collection of oral histories, the distribution of a wider community survey, and the engagement of the public through more meetings and activities over a shorter period. Students with prior experience with community engagement emerged as team leaders, translators, and facilitators. Across the courses, students of color were especially empowered to engage with residents and continued to be involved with the Griffin Heights neighborhood after the project. Students’ consistent presence in the community at church services and volunteer events, both during and after the course ended, signaled their commitment to the process and community. These students were also able to adapt and respond to changes in the process timeline, attend additional meetings, and visit more sites to administer the community survey. However, this also meant that as city bureaucracy extended timelines, students of color went above and beyond to invest substantial time and effort to connect with residents in this historically excluded community of color.

5.2. Importance of Community Buy-In

The Division of Neighborhood Affairs prioritized seeking prior buy-in from the pastors, community leaders, and the GHNA in order to successfully engage residents and move the Neighborhood First planning process forward. However, there were several barriers to engagement that limited the success of different components of the project. The GHNA membership was closely tied to the membership of one of the churches, Griffin Chapel. As a result, representation at CAT meetings from members of other churches beyond the pastors was much smaller and more energy was spent on recruitment than actual engagement with a representative collective. Strategically, it made sense to use the monthly meetings to ensure a range of opportunities to dialogue and come to consensus while allowing new voices to enter the conversation. However, representation was often limited to the same elders in the community. As attendance dwindled over time, continuing to hold meetings seemed largely performative, with limited concrete outcomes. While city planners set expectations for the necessary extent of community consultation, the process achieved thematic saturation, where meetings no longer introduce new themes to discussion. Moreover, the GHNA indicated they were ready to move forward with finalizing and implementing the action items FSU DURP developed early in the process.

5.3. Communication and Capacity

The community survey took a significant bandwidth to distribute through canvassing. Given the intensive nature of the survey distribution and length of the survey, we learned that to improve the response rate, there was a need for: (1) a shorter alternate survey for younger respondents; (2) an increase in the capacity of surveyors to assist and monitor respondents when necessary; (3) an incentive to encourage more community leaders and participants to partake in survey dissemination as leads; and (4) an improvement in accessibility for disabled and elderly respondents through surveyor training and research.

We also learned that face-to-face engagement at the church services and community center was the most effective way of getting information to and from the Griffin Heights community. Traffic on the Facebook site was low and did not appear to reach a wide audience, even though the site was turned over to a community resident. The lack of engagement from the schools presented a formidable barrier to disseminating the survey, accessing the younger population in the community, and recruiting youth leaders to join the Neighborhood First planning process through the GHNA. We were unable to meaningfully connect with school administrators. We did not receive approval to hold the youth event at the school or disseminate information or surveys for students to take home to their parents. The low attendance at the youth event was compounded because it was held at a location outside of the Griffin Heights community on a weekend that was packed with other neighborhood events. A community resident saved the event by transporting children from the Griffin Heights apartments to it by car, but without this intervention the event would have failed to train students to administer a charrette and capture the perspectives from the youth of Griffin Heights. The input from this event was presented to the CAT meeting but it was unclear how much was incorporated into the final plan.

5.4. Bureaucracy and Institutional Constraints

Procedural accountability is important for legitimizing public engagement—planners must document and demonstrate that they achieved what they set out to achieve in adherence to administrative and budgetary regulations [44]. Consequently, there is often no room within highly structured city processes to adapt and change in response to changing needs or circumstances at the neighborhood scale. Conceptual principles of effective culturally competent engagement have been elaborated in the literature [45,46,47,48]. However, engagement processes in practice are iterative and contextual, evolving as the actors deliberate over time. The successes of a structured long-term engagement process in one minority neighborhood can provide important lessons that can inform future engagements. However, these outcomes may not necessarily translate to another minority neighborhood even if they appear to face similar issues.

The Neighborhood First planning process was envisioned to provide a collaborative planning platform for communities to identify and shape community priorities in tandem with city planning staff. However, delegation of the decision-making power to the community was constrained by the structural controls administered from the top-down. In an attempt to generalize the process across communities in Tallahassee, city staff strictly defined components of the process with little room for adaptation to neighborhood context or community dynamics. The Griffin Heights Neighborhood First planning process closely mirrored the process previously adopted in the Greater Bond neighborhood, located in south Tallahassee. Although facing similar socio-economic pressures, the community dynamics and level of political activism and engagement varied significantly between the two neighborhoods. There was greater division among community leaders in the Greater Bond neighborhood. Thus, the deliberative process needed several months in order to build consensus among the many vocal leaders in the community with different visions and priorities for the neighborhood. This was not necessary in Griffin Heights. However, the city nonetheless established and transmitted standardized timelines from the Greater Bond process to the Griffin Heights process. Thus, the Neighborhood First planning process continued long after FSU DURPs formal participation, attempting to replicate the timeline that Greater Bond required to achieve consensus, requiring community elders to attend monthly meetings until they met the city’s predetermined milestone for due deliberation (after more than two years). Participating in a longer process consumed Griffin Heights residents’ time and resources without much additional benefit. Instead of garnering novel ideas or energy from new participants, the extended process prolonged demands on the time, energy, and effort of an elderly and less politically active group of residents. With most of the participants in consensus early on, there was room in the process to be adapted and tailored to the community’s capacity to engage. Rigidity in the engagement process achieved the procedural accountability goals of the city, but lagged in efficiency and effectiveness of outcomes.

5.5. Financial Constraints

The expectation that the community should engage in a long-term process is particularly problematic when there is no funding to follow-through to implementation. The small budget allocation for the Neighborhood First planning process limited the accommodations provided at meetings such as food, outreach materials, and incentives to participate. In-kind donations from community partners and FSU DURP played an important role in closing the gap, but this is not a sustainable or even adequate fix. Further, the identified lack of funding for future projects and interventions rendered the planning process irrelevant and performative. In CAT meetings as well as People and Places committee meetings, community members continually questioned “where was the money coming from.” Not having established dedicated sources of funding and implementation partners prior to initiating the engagement process can dampen enthusiasm and incentives for residents to participate. The Division of Neighborhood Affairs acknowledged these concerns and incorporated them into the CAT prioritization process. The committee identified potential sources of funding and strategies to access these funding pots. Although the Urban Design Plan was presented at numerous Open Houses and many elements incorporated into the draft Neighborhood First Plan, it remains to be seen what if any of the ideas are funded and implemented. Without clear answers on when and how much funding would be available, participants and students continued to seek evidence of commitment and accountability in lieu of the promise of potential funding in the future. If all was for naught, it is difficult to claim that the project meaningfully engaged or empowered community members. It also raises pedagogic concerns. While some students connected with African-American community members and gained a deeper appreciation of their experiences, there is also a risk that the perceived tokenism of the exercise may reinforce some students’ belief that engaging the community serves no broader purpose and simply wastes a lot of people’s time. To avoid this perception and meaningfully impart the value of these processes, it is vital that they result in meaningful change for the community.

6. Conclusions

Much can be gained when university partners serve as conduits or bridges between the city and the community. Students learning through a community engaged applied planning process that meaningfully incorporates community input has the potential to be broadly beneficial for all parties [11,12,13]. It can provide important applied experiences for students who have not previously engaged African-American community members. This learning can effectively reinforce the concepts covered in course material and advance the broader goals of building a more inclusive approach to planning practice. However, stark realities of participating in the planning game, where it feels like the gestures to community engagement only distract residents while the real ball is hidden elsewhere, can quickly erase idealistic notions of shared mutual benefits.

The city–community–university partnership provided students with applied insights into the complexities and considerations of engaging with a historically marginalized and vulnerable group. Beyond the practical lessons of process based design and plan making, these applied courses provided students with more intangible opportunities for reflexive praxis as they examine their positionality in the planning process and how their presence as individuals and as a collective influenced and was influenced by the process. The partnership established a multi-directional network of exchange, negotiation, and learning which further enhanced the capacity on the ground to move the process forward.

However, the Neighborhood First planning process faced significant institutional challenges that could not be addressed through the university–community partnership. Participation in this process revealed the extent to which it had been designed as a prescribed process. It showcased the burden that inflexibility in these processes can impose on a community with limited capacity for sustained activism. It also highlighted how rigidity in deliberative processes can alienate community members [20,21].

While this provided a potentially instructive experience to students, highlighting the constraints of bureaucratic processes, it also risked reinforcing preconceived notions that engaging marginalized communities is simply a token gesture. By structuring a transferable structured engagement process from the top, the Neighborhood First planning process dampened the iterative and translational nature of planning from the bottom up. This broadly echoed established critiques of the ways that rhetoric of university–community partnerships often masks power dynamics that continue to permeate these processes [17,18,19]. Rather than adhering to the “one process fits all” approach, programs such as Neighborhood First should be structured to be flexible, adaptive, and responsive to the neighborhood context and capacity. Including monitoring and evaluation checkpoints throughout the process can create iterative feedback loops to inform the direction and retailoring of the process to channel the community dynamics towards a timely endpoint.

Sustaining community excitement and buy-in over the long-term can open opportunities for true accession to the higher rungs of Arnstein’s ladder of engagement [49]. When asking residents to commit time and energy to work on long-term planning processes, we must also work to generate wins, successes, and demonstrations of commitment over the short term. Projects identified in the planning process as low-hanging fruit that may not require significant levels of funding or approval can demonstrate to residents the city’s commitment to follow-through and provide examples of the potential for future projects.

Funding continues to be a significant constraint when pursuing any long-term neighborhood planning process [22]. These initiatives should not be undertaken if there is no likelihood of funding support. Planners must do the pre-work of identifying existing and potential sources of funding to support the length of the planning process from visioning at small scale efforts such as meetings to implementation of projects over the medium and long terms. As the planning process proceeds, these planners should be strategically lobbying for additional funding in order to make the ideas discussed and agreed upon a reality. Realism early in the process regarding in the availability of funding promotes transparency and sets the expectations for the type and scale of projects that are feasible

Along with developing funding sources, planners need to develop and nurture relationships with community residents, leaders, and partners in order to build the capacity, redundancy, and diversity into community networks. Partners such as the schools and businesses can serve as highly effective conduits of information, resources, and support. These partners can then in turn reduce the amount of on-the-ground work required by a department with limited staff and resources. Community residents outside of the GHNA may also bring fresh energy, perspectives, and connections.

Finally, an effective community engaged planning process must not only promote equity and inclusion in the planning stages but also lead to equitable and just outcomes for the community [50,51]. Students and faculty struggled to reconcile the desire to serve as community advocates without reinforcing existing patterns of development that marginalize communities of color. While the classes opened the space for the Griffin Heights neighborhood to engage in visioning the future of their community, it also revealed that without changing the status quo, many city planning policies would continue to perpetuate or worsen development pressures and operate in direct conflict with visions charted by the residents during the engagement process. Thus, it is necessary to explicitly engage the development assumptions and priorities that underpin city planning processes and acknowledge the distinct spatial vision of African-American communities [23]. Efforts must be made to connect robust engagement processes with a progressive policy environment to enable change. Policies must be revised and updated in tandem to include planning tools which facilitate and improve the likelihood of equitable outcomes such as anti-displacement policies to protect the neighborhood as it undergoes redevelopment, such as form based codes, inclusionary zoning, community land trusts, rent control, or tax abatement policies.

Honing the skills required to be an effective neighborhood planner come with time, exposure, and commitment to fostering equity, justice, and inclusion in communities. Community engaged courses immerse students in the field, where they can critically assess and apply theories discussed in the classroom to advance community priorities [52,53,54,55,56,57]. Students are often novices to this format of learning and their inexperience, while expected, can also be a threat when involved in complex community politics and where the stakes to get things right are high in historically marginalized communities of color. However, learning these skills and lessons before entering the planning profession can prepare students to anticipate and understand the commitment, competence, creativity, and conviction required when planning with African-American neighborhoods such as Griffin Heights.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.J., T.H., and T.M.; methodology, A.J. and T.H.; formal analysis, A.J., T.H. and T.M.; investigation, A.J. and T.H.; resources, A.J. and T.H.; data curation, A.J. and T.H.; writing—original draft preparation, A.J., T.H., and T.M.; writing—review and editing, A.J., T.H. and T.M.; visualization, A.J.; supervision, A.J. and T.H.; and project administration, A.J. and T.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the important contribution of all the Griffin Heights community members who participated in these planning processes, as well as the City of Tallahassee Division of Neighborhood Affairs. We also thank the Fall 2018 class of URP 5743 Neighborhood Planning and Spring 2019 classes of URP 5059 Public Participation and Community Involvement and URP 5881 Urban Design, without which the Griffin Heights planning process would not have been possible.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Shea, J. Sustainable Engagement? Reflections on the development of a creative community-university partnership. Gateways 2011, 4, 136–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, H., Jr.; Luter, D.; Miller, C. The University, Neighborhood Revitalization, and Civic Engagement: Toward Civic Engagement 3.0. Societies 2018, 8, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehlenz, M.M. Gown, Town, and Neighborhood Change: An Examination of Urban Neighborhoods with University Revitalization Efforts. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2019, 39, 285–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peck, J. Struggling with the Creative Class. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2005, 29, 740–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickren, G. “Where Can I Build My Student Housing?”: The Politics of Studentification in Athens-Clarke County, Georgia. Southeast. Geogr. 2012, 52, 113–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moos, M.; Revington, N.; Wilkin, T.; Andrey, J. The knowledge economy city: Gentrification, studentification and youthification, and their connections to universities. Urban Stud. 2019, 56, 1075–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, V. The Roles of Universities in Comnunity-Building Initiatives. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 1998, 17, 302–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiewel, W.; Lieber, M. Goal Achievement, Relationship Building, and Incrementalism: The Challenges of University-Community Partnerships. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 1998, 17, 291–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bringle, R.G.; Hatcher, J.A. Campus-Community Partnerships: The Terms of Engagement. J. Soc. Issues 2002, 58, 503–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allahwala, A.; Bunce, S.; Beagrie, L.; Brail, S.; Hawthorne, T.; Levesque, S.; von Mahs, J.; Visano, B.S. Building and Sustaining Community-University Partnerships in Marginalized Urban Areas. J. Geogr. 2013, 112, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buys, N.; Bursnall, S. Establishing University–Community Partnerships: Processes and Benefits. J. High. Educ. Policy Manag. 2007, 29, 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levkoe, C.Z.; Brail, S.; Daniere, A. Engaged pedagogy and transformative learning in graduate education: A service-learning case study. Can. J. High. Educ. 2014, 44, 68–85. [Google Scholar]

- Ashley, A.J.; Vos, J. The Department as a Third Sector Planner: Implementing Civic Capacity through the Planning Core Curriculum. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2015, 35, 501–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCreary, T.; Murnaghan, A.M. Remixed Methodologies in Community-Based Film Research. Can. Geogr. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamble, S. Community. In Keywords for Radicals: The Contested Vocabulary of Late-Capitalist Struggle; Fritsch, K., O’Connor, C., Thompson, A., Eds.; AK Press: Chico, CA, USA, 2016; pp. 103–109. [Google Scholar]

- Mulrennan, M.E.; Mark, R.; Scott, C.H. Revamping Community-Based Conservation Through Participatory Research. Can. Geogr. Geogr. Can. 2012, 56, 243–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shefner, J.; Cobb, D. Hierarchy and Partnership in New Orleans. Qual. Sociol. 2002, 25, 273–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyle, M.-E.; Silver, I. Poverty, Partnerships, and Privilege: Elite Institutions and Community Empowerment. City Community 2005, 4, 233–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherry, D.J.; Shefner, J. Addressing Barriers to University-Community Collaboration: Organizing by Experts or Organizing the Experts? J. Community Pract. 2004, 12, 219–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewar, M.E.; Isaac, C.B. Learning from Difference: The Potentially Transforming Experience of Community-University Collaboration. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 1998, 17, 334–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prins, E. Framing a Conflict in a Community-University Partnership. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2005, 25, 57–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, H.S. Fantasies and Realities in University-Community Partnerships. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2000, 20, 234–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipsitz, G. How Racism Takes Place; Temple University Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, P.H. Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Kelley, R. Race Rebels: Culture, Politics, and the Black Working Class; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Ragin, C.; Becker, H. What Is a Case? Exploring the Foundations of Social Inquiry; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Stake, R. The Art of Case Study Research; Sage: Thousand Oakes, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Flyvbjerg, B. Five Misunderstandings about Case-Study Research. Qual. Inq. 2006, 12, 219–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardwick, S.W. Case Study Approach. In International Encyclopedia of Human Geography; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2009; pp. 441–445. ISBN 978-0-08-044910-4. [Google Scholar]

- Winkler, T. At the Coalface: Community–University Engagements and Planning Education. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2013, 33, 215–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]