Abstract

Implicit or unconscious bias is commonly proposed to be responsible for women’s underrepresentation in academia. The aim of this scoping review was to identify and discuss the evidence supporting this proposition. Publications about unconscious/implicit gender bias in academia indexed in Scopus or psycInfo up to February 2020 were identified. More than half were published in the period 2018–2020. Studies reporting empirical data were scrutinized for data, as well as analyses showing an association of a measure of implicit or unconscious bias and lesser employment or career opportunities in academia for women than for men. No studies reported empirical evidence as thus defined. Reviews of unconscious bias identified via informal searches referred exclusively to studies that did not self-identify as addressing unconscious bias. Reinterpretations and misrepresentations of studies were common in these reviews. More empirical evidence about unconscious gender bias in academia is needed. With the present state of knowledge, caution should be exercised when interpreting data about gender gaps in academia. Ascribing observed gender gaps to unconscious bias is unsupported by the scientific literature.

1. Introduction

Implicit or unconscious bias is commonly assumed to be responsible for women’s underrepresentation in academia. An increasing number of publications are concerned with gender gaps in academia and propose unconscious bias as a major cause. The theory about unconscious bias is being advanced not only in the scientific literature, but also in reports from governments, universities, and professional associations who call for action against it (e.g., [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37]).

A commentary in the prestigious medical journal, Lancet, summarizes the situation succinctly:

“The concept of implicit bias, also termed unconscious bias, and the related Implicit Association Test (IAT) rests on the belief that people act on the basis of internalized schemas of which they are unaware and thus can, and often do, engage in discriminatory behaviors without conscious intent. This idea increasingly features in public discourse and scholarly inquiry with regard to discrimination, providing a foundation through which to explore the why, how, and what now of gender inequity”.[38]

The present article reviews the published empirical evidence about unconscious bias in academia in relation to women’s careers. The scope of the review includes publications that have used the term unconscious or implicit bias in the title, abstract, or keywords. These will be said to self-identify as being about unconscious bias. Reviews and commentaries about unconscious bias often refer to studies of bias against women in academia that do not self-identify as being about unconscious bias, but re-interpret them as being about unconscious bias. The present paper gives examples of such reinterpretations and discusses their validity.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

A systematic, qualitative review of the published literature of empirical data pertaining to unconscious gender bias in academia was performed. A quantitative synthesis (meta-analysis) was neither possible nor warranted in view of the findings of the qualitative review.

2.2. Data Collection

The literature search was made in Scopus and psycInfo. Scopus is the largest database of peer-reviewed papers, encompassing 46 million references from 19,500 journals from a wide range of disciplines. psycInfo is the most comprehensive database of psychological literature relevant for this review.

Titles, abstracts, and keywords were searched for the terms:

((("unconscious bias" AND (gender OR women OR woman)) OR ("implicit bias" AND (gender OR women OR woman))))

2.3. Data Analysis

A total of 425 publications were identified. A total of 321 were evaluated on the abstract alone, 98 were evaluated on the full paper, and 6 were not evaluable on the abstract alone, could not be found at the Royal Danish Library or on the WorldWideWeb, and were thus excluded.

After removal of book reviews, conference papers, conference reports, dissertations/theses, and publications about healthcare disparities, legal aspects of discrimination, and other publications not concerned with gender bias in academia, 137 remained.

Of these 137 publications, 54 reported original empirical data about gender bias, and 83 were editorials, commentaries, and reviews based on existing data. The 6 review papers were concerned with gender bias and gender gaps, and none of them encompassed a comprehensive review of implicit or unconscious bias in academia. All professed unconscious bias as a cause of gender disparities in academia.

2.4. Limitations of the Data Collection Method

Publications of interest may have been overlooked in the search, either as a result of incompleteness of the databases or the scope of the search. An informal check was made via Google Scholar for original data about unconscious gender bias in academia. The search in Google Scholar did not disclose original empirical data among the first dozens of hits. Google Scholar’s search algorithm prioritizes the highly cited publications [39]. In a setting with scarcity of original empirical data and a great interest of the scientific community in the subject, one would expect publications with actual empirical data to rise to the top of the search very quickly. Thus, the lack of such publications in the first pages of search results supports the absence in Scopus and psycInfo.

It is possible that studies whose aim was not to study unconscious bias might present evidence of unconscious bias even if the authors did not use the terms unconscious or implicit bias. This shortcoming of literature searches applies to any summary of evidence for a theory, but might be more pertinent when evidence is scarce. Indeed, commentaries, reviews, and reports commonly include re-interpretations of such publications as evidence in support of the theory. Some examples of such studies and the validity of their re-interpretation as being about unconscious bias have been included in the discussion section of this paper. These publications, which were not found in the search, are not included in the enumeration of the search results.

3. Results

In 18 of the 54 publications with original data, the data did not provide evidence of bias against women. The remaining 36 publications reported bias against women’s careers in academia [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,40,41]. Two of the 36 [40,41] did not clearly propose unconscious bias as an explanation of the findings. The 34 studies that did propose unconscious bias as an explanation of the findings were reviewed in order to identify studies showing an association of a measure of implicit or unconscious bias and an endpoint that could at least hypothetically indicate lesser employment or career opportunities for women. No publications of empirical data to document such an association could be identified.

Rojek et al. [29] present a typical example of a study that claims to address unconscious bias but, at closer inspection, turns out not to. The authors analyzed medical student evaluations and identified differences by gender, with, for example, the word “lovely” being used more often about women and “scientific” more often about men. The authors state that these findings “raise concern for implicit bias in narrative evaluation”. However, clearly, the study itself does not provide evidence in favor of this interpretation: For example, the evaluators could know very well that they regard the women as more lovely and the men as more scientific, in which case they would be consciously—as opposed to unconsciously—biased. They could, in principle, also be correct. The study can at most conclude that there was bias—unqualified as to conscious or not. Though the study is compatible with unconscious bias, it does not demonstrate it. The study is typical in that it presents statistics about differential treatment of men and women in academia and concludes offhand that the statistics show unconscious bias. What should be demonstrated is taken for granted; the reasoning is circular.

Like the Rojek study, the 34 studies that purported to demonstrate unconscious bias in effect assumed the conclusion. This is further elaborated upon in the section “Petitio principii” below.

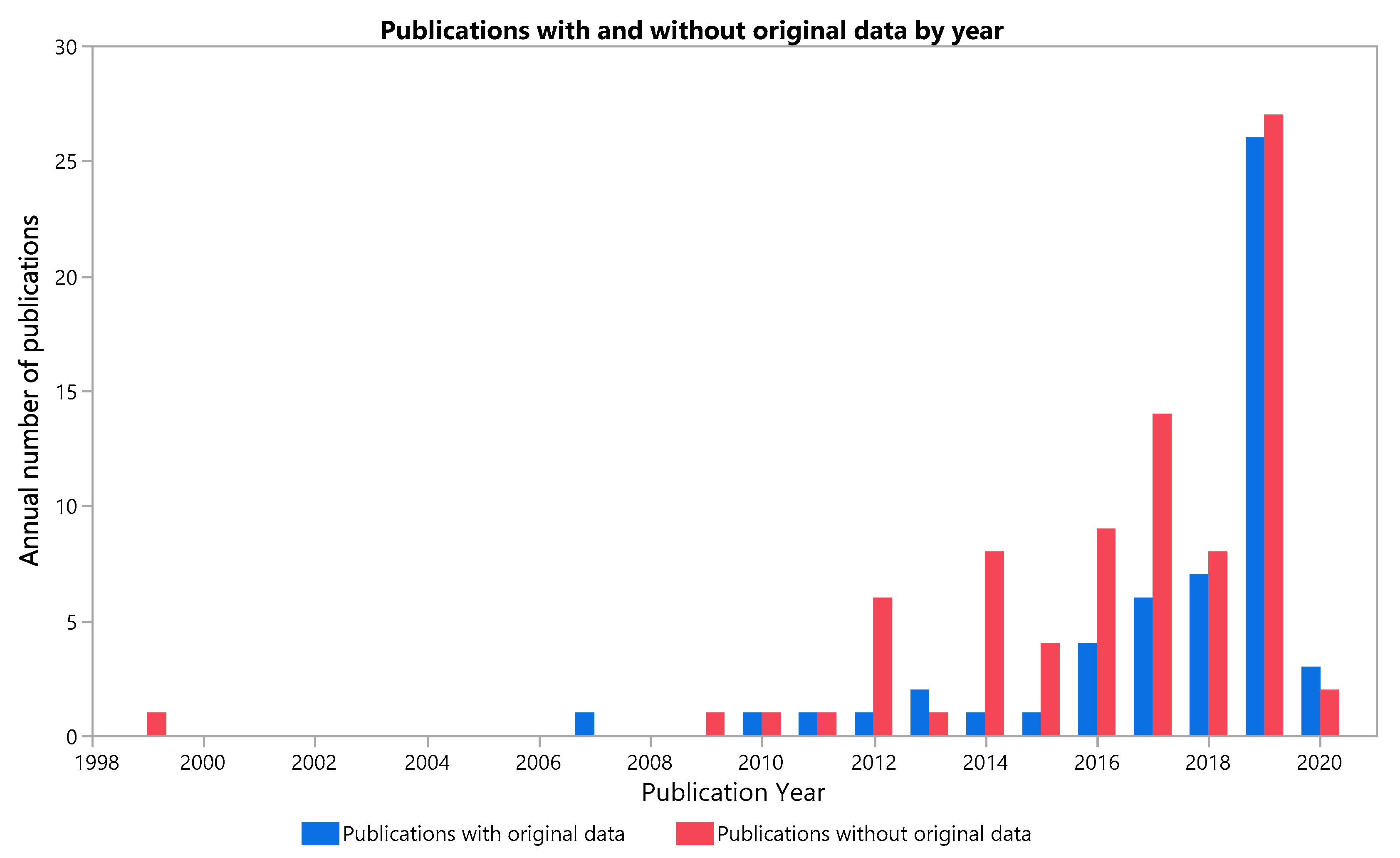

Figure 1 shows the annual number of publications for the 54 publications with original data and the 83 editorials, commentaries, and reviews. For both groups of publications, there is an increase over the last decade. It may be noted that the increase in publications with original data started after the increase in secondary publications. More than half of the publications are from 2018–2020.

Figure 1.

References from the literature search, with (54) and without (83) original data, by annual number.

The literature search did not identify systematic reviews of unconscious bias in academia. Two such reviews were identified by internet searches [37,42]. The original articles identified from these reviews are discussed below. There was no overlap between these references and the references identified in the literature search. Details about the studies that are mentioned in the text are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Studies referenced as evidence for unconscious or implicit bias in the reviews and commentaries discussed below.

4. Discussion

The literature search did not identify any empirical data demonstrating a role of unconscious bias as a cause of gender gaps in academia. This notwithstanding, an increasing number of studies profess to report data about unconscious bias, and reviews, commentaries, editorials, and reports second the idea, especially in the last 4–6 years (Figure 1).

The theory of implicit or unconscious bias originates in the two-system theory of the mind. Kahneman and others have proposed that the human mind processes information with two systems: System 1, which employs heuristics for quick decision making that does not need conscious processing, and System 2, which examines the available information more thoroughly and makes deliberate and reasoned decisions. Importantly, System 2 can overrule the automatic reactions of System 1; it can, as it were, overcome the biases of System 1. However, it is, in Kahneman’s words, slow and lazy. We are, in other words, steeped in our prejudices unless we make an effort to overcome them [59].

System 1 uses heuristics, which are, in the simplest sense, rules of thumb that process information in a quick and efficient way. Unfortunately, this kind of thinking is also error-prone. Tversky and Kahneman described the representativeness, availability, and anchoring heuristics and the 20 types of biases that they can lead to in their seminal 1974 paper [60]. Many other heuristics have been described since [59].

Most of our behavior is decided by System 1. We would not get anything done if we were to rely on System 2 for everything. System 1 relies on our prejudices; for example, about gender roles, what women can do and cannot do. So, here you are: The biases that we see are due to System 1.

The model fills a gap that seems to have developed as expression of overt sexist views have become increasingly rare in academia. Few professors would vent the opinion that women are unsuited to be professors. Something other than explicit bias must be at play to explain why women seem to have less favorable careers in academia than men, and here, the theory of implicit bias is a godsend. Even though people do not express biased views, they may still make biased decisions, for example, when hiring staff.

The central tenet of the two-system theory is that we process information and make decisions with a psychological setup than can be biased. However, System 2, when called upon, can produce more worked-out rational decisions based on all available information. In short: Any decision can be biased, but it may not be. Potentially, the biases ensuing from heuristics could be present anywhere, and it is tempting to overstretch the theory to explain most anything. However, whether heuristics actually do play a role in a concrete setting cannot be decided without close inspection.

The two-system theory has been known since the 1970s. In the late 1990s, something decisive happened. Greenwald et al. [61] introduced at test method, the Implicit Association Test (IAT), which turned the attention unilaterally toward System 1. The test measures how long it takes for the test person to associate two pictures with each other; for example, how long it takes to associate “good” with a photo of a lean person compared to how long it takes to associate the word with an obese person. If the difference exceeds 0.3 seconds, the test will read out bias.

The IAT became big business. Millions have taken the test online and experienced it as an eye opener. Even people who thought they were neutral to weight, gender, sexual preferences, race, etc. find out that they are biased—according to the test.

Bias as measured by the IAT was soon held to be the explanation for racial discrimination, discrimination of women, obese, homosexuals, etc., and an industry of courses grew up that were designed to correct the biased. However, in recent years, evidence has mounted that the IAT does not predict behavior [62]. The reactions of System 1 as measured by IAT have no bearing on what we actually do. Even the inventors of the test have been forced to admit it [63].

In the meantime, System 2 had been forgotten. IAT measures events which play out in less than a second. However, no one makes a hire in a second. Conceivably, people consider carefully and, unless they are clearly chauvinists, control their heuristics and employ the best candidate. Whilst System 2 is neither the focus of Greenwald and Banaji or Kahneman, others have explored how System 2 is a corrective to System 1; for example, Stanovich [64]. Incidentally, Stanovich mentions the hiring of staff as an example where System 2 plays the dominant role [64] (p. 20).

Unconscious/implicit bias/heuristics could theoretically lead to discrimination of women in academia, but the theory is insufficient to substantiate the claim. There are theoretical reasons to believe that System 1’s tendencies to be biased may be countered by System 2. So, before concluding that there is unconscious gender bias in academia, one has to show that such bias is indeed present.

This crucial consideration seems to have been overlooked or neglected. How this has happened is not easily pinpointed. It is, however, possible to discern some of the methods by which the impression has been created of this being a well-established theory. The below discussion presents examples of reports and studies that have played a role in building the impression of evidence for implicit bias in academia. The discussion does not purport to be exhaustive. Therefore, the following focuses on the principles, rather than the individual cases.

4.1. Fallacies of Argumentation

Some fallacies of argumentation are so old that they have Latin names.

4.1.1. Answer a Different Question (Ignoratio Elenchi)

One commonly applied method for creating the impression of evidence is the substitution of the question. If you cannot answer the real question, then answer a different one and conclude for the first, like so: If you cannot find evidence of unconscious bias against women, find something about bias against women and conclude that there is evidence for unconscious bias against women. The method was first described by Aristotle, but has probably been used as long as people have disagreed.

Gvozdanovic and Maes’s report, ”Implicit bias in academia” [37], is a prime example of ignoratio elenchi. The report claims that implicit bias is a major hindrance for women’s careers in academia and further asserts that there is ample scientific evidence to support this claim. The report presents a literature review which is meant to substantiate this claim, but the reader will note that none of the referenced studies mention unconscious or implicit bias, only unqualified bias. I have gone through all publications (for details, see Table 1), and there is nothing about unconscious bias.

This is a main feature of the reports about unconscious bias: “Unconscious bias” is used about the supposed unconscious resistance to equal opportunities for men and women, whereas “bias” without “unconscious” is used when referencing studies of the phenomenon. The trick lies in the ambiguity. Implicit bias is the same as unconscious bias, which is the same as bias. Every article about bias is now an article about unconscious bias. What should be demonstrated is now proven just by juggling the words.

Cornish and Jones’ literature review ”Unconscious bias and higher education” [42] uses the same method, although on a smaller scale. They only reference two articles, neither of which is about unconscious bias (see Table 1).

Atewologun et al. [65] (p. 11) open with the statement “[Unconscious Bias Training] is often designed, developed, and modified on the basis of the large body of research on unconscious bias” and justify this claim by stating that there is “ample research documenting the influence of stereotypes on workplace evaluations and decision making”. However, this is a different question from the one which is of interest here.

4.1.2. Invent Auxiliary Theories (Ad Hoc Hypotheses)

Sometimes, the data speak so clearly against the preconceived theory that the contradiction cannot be ignored. This is where ad hoc hypotheses are helpful.

A Danish “Taskforce for More Women in Research” appointed by the Ministry of Education and Research looked at data from the Danish universities [35]. The taskforce found that when there were qualified applicants of both genders for an academic position, the women had higher success rates than the men (this has been known since the 1990s, thanks to Bertel Ståhle’s analyses [66]). The taskforce proposed this ad hoc hypothesis:

“One interpretation of the numbers is that women may tend to apply later than men, that is, when they are more certain to be qualified. The female researchers are good once they are in a position to apply…, but there is likely to be a number of mechanisms which keep women from applying. It is a leadership task to address these”.[35] (p. 26, my translation)

There is no independent evidence for the ad hoc hypothesis. This notwithstanding, the taskforce pronounces this a problem that management must solve.

Lerback and Hanson [58] claim that journals invite too few women to review papers, and that this puts women at a disadvantage in their academic careers. Apart from their analyses being flawed (Skov and Knudsen, submitted to Nature), Lerback and Hanson also find that articles authored by women have a higher chance of being accepted for publication than articles by male authors. They offer two explanations:

“It could imply that female …. authors are enjoying ‘reverse sex discrimination’….. Or—and this is the possibility we favor—the higher acceptance rates reflect the authors’ more considered approach when submitting manuscripts, including better targeting of papers to a journal”.

Why do Lerback and Hanson favor the last hypothesis? It cannot be by way of their data.

4.1.3. Assume the Conclusion (Beg the Question, Petitio Principii)

The above literature search identified 34 publications of original data that were presented by the authors as evidence of or interpretable as unconscious or implicit bias [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34]. At closer inspection, the studies might be compatible with the theory of implicit bias, but they did not provide independent empirical evidence to support the theory. All of these publications assumed the conclusion.

Another implementation of petitio principii is to create an expectation that the text includes an argument and then to present the data that are to be explained. Again, the work of Gvozdanovic and Maes [37] is exemplary. Under the heading ”The impact of implicit gender bias on working conditions”, the report presents statistics about vertical segregation, gender pay gaps, and gender differences in temporary and permanent employment; in other words, the data that the report sets out to explain.

4.2. Misinformation

In addition to fallacies of argumentation, there are various types of misinformation.

4.2.1. Data do not Mean Anything. It Is the Story You Tell about the Data that Means Something

In one of the clearer examples of misinformation, the narrated story contradicts the referenced paper. Robertson et al. [56] consider whether there can be bias against women in the evaluation of scientific proposals and articles, and go on to say that "there is widespread evidence of the existence of “implicit bias” in science…", referencing [57]. The source is a one-page summary of a conference. There are no data. Incidentally, the conference reported that women’s chances of getting a publication accepted were as high or higher than men’s. The implicit bias mentioned in the summary concerns authors from non-Western countries, not women.

Gvozdanovic and Maes [37] cite a paper by Maliniak et al. [52] in which 3000 papers were analyzed (see Table 1). Maliniak et al. concluded that men cite men and women cite women; therefore, women are less cited than men. Gvozdanovic and Maes make the following of it:

“Papers, ostensibly authored by males, acquire higher scores on quality than papers ostensibly authored by females”.[37] (p. 13)

The publications are, however, real, not “ostensibly authored”, and they were not scored for quality. There is no similarity between Gvozdanovic and Maes’ summary and the actual content of the paper.

The stories told about Moss-Racusin et al. [49] are more subtle. This study has become the mainstay in the literature about unconscious bias in academia, which is somewhat surprising considering that the study is not about unconscious bias, and, if it should give rise to any hypotheses about unconscious bias, it would be that unconscious bias is not the explanation of the study findings. As described in Table 1, professors rated male-named applications higher on all parameters than female-named applications. However, further analyses showed that this only applied to professors who had a negative attitude towards women as measured with the “subtle bias” questions. It may be assumed that the professors were quite aware of their negative attitude, so there was no unconscious bias there.

Considering the professors who did not have a bias against women, Moss-Racusin et al. must be understood to show that they did not discriminate against women. The theory about unconscious bias is that unconscious bias causes us to make the wrong choices even when we want to do the right thing. However, according to Moss-Racusin et al., those who wanted to do the right thing actually also did the right thing. As such, Moss-Racusin et al. speak against the hypothesis about unconscious bias.

This notwithstanding, Grogan [50] unreservedly claims that Moss-Racusin et al. showed unconscious bias:

“Importantly, faculty gender does not influence these results, meaning that unconscious gender bias is pervasive and not limited to a particular gender”.[50] (p. 4)

This is not what Moss-Racusin et al. show.

The older reports stick to answering the question of whether the study shows discrimination. Cornish and Jones [42] (p. 8) write in their report about unconscious bias:

“… women in STEMM (science, technology, engineering, mathematics, and medicine) departments (Moss-Racusin et al, 2012) are just as likely to discriminate against female candidates as their male counterparts.”

Gvozdanovic and Maes [37] copy Cornish and Jones:

“… female natural scientists in science, technology, engineering, mathematics, and medicine (STEMM) departments (Moss-Racusin et al., 2012) are just as likely to discriminate against female candidates as their male counterparts.”

4.2.2. Create an Impression of More Data than There Are

In this strategy, commentaries and other secondary literature are cited as if they were original articles of empirical studies. New authors regularly appear who reference the same few studies. This creates the opportunity for referencing the new authors as if they presented new data. ”She figures 2018”, a report from the European Commission, writes:

“It should be noted, however, that research also shows that unconscious gender bias in favor of men is not limited to male faculty members (Grogan, 2018)”.[36] (p. 129)

This looks as if Grogan reports new data about unconscious bias. This is not the case. Grogan is just interpreting Moss-Racusin et al. and does it erroneously—Moss-Racusin et al. do not demonstrate unconscious bias. There are many such examples, and they can only be disclosed by going back in the chain of publications; here, first to Grogan, then to Moss-Racusin et al. It usually turns out that the original data do not show what they are being cited for.

Again, Gvozdanovic and Maes [37] excel. They reference a review article, [54], which refers to another review article [45], which does not report what Gvozdanovic and Maes cite it for:

“For women to be deemed equivalently hirable, competent, or worthy of promotion in male-gender-typed professions, they must demonstrate a higher level of achievement than identically qualified men.”

The same text is, however, to be found in Kaatz et al. [54], whom Gvozdanovic and Maes have copied. None of it is about unconscious bias.

As noted above, some of the reviews and commentaries do not refer to publications that self-identify as being about unconscious bias, but (erroneously) re-interpret studies that do not self-identify as such. This is probably how the increase in the annual number of secondary publications has come to precede the increase in studies reporting original empirical data, as seen in Figure 1.

As always, the absence of proof does not prove absence. Under this viewpoint, there would be a need for further studies to demonstrate that unconscious bias does indeed explain at least part of the gender gaps in women’s careers in academia. The prospects for producing such data would seem bleak, since unconscious bias is, almost by definition, difficult to study. A simple modification of the Moss-Racusin et al. study design might, however, be fruitful. As in the original study, applications that are identical except for the name could be sent to two groups of professors, asking them to rate the applications. The professors should indicate whether they had any gender preference for new hires to the position in question, and the data analysis should be restricted to those who indicated an egalitarian view. At first sight, this modification might seem counterproductive, since the purpose of the study would be given away and the professors could weigh their responses so as not to be biased against the female applicant—they could provide socially desirable replies. However, this is precisely how the experiment would address the core of the claim about unconscious bias: That our decisions are biased by prejudices that we are not aware of, and that we are basically unable to do what is deemed socially desirable.

Whether by this or other methods, more studies would seem warranted. Until more evidence is available, and as matters stand, caution should be exerted in the interpretation of gender gap statistics in academia. These cannot be ascribed off-hand to unconscious bias. There is not sufficient evidence to support this interpretation.

5. Conclusions

Gender gaps in academia are commonly ascribed to unconscious bias. However, inspection of the publications that advance this theory reveals a lack of empirical data and a multitude of argumentation fallacies and misrepresentations. Whereas unconscious bias could theoretically take place and produce gender gaps in academia, the theoretical possibility should not be a substitute for analyzing real data. No convincing data have been published.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Lincoln, A.E.; Pincus, S.; Koster, J.B.; Leboy, P.S. The Matilda Effect in science: Awards and prizes in the US, 1990s and 2000s. Soc. Stud. Sci. 2012, 42, 307–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochran, A.; Hauschild, T.; Elder, W.B.; Neumayer, L.A.; Brasel, K.J.; Crandall, M.L. Perceived gender-based barriers to careers in academic surgery. Am. J. Surg. 2013, 206, 263–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, S.M.; Hillard, A.L.; Schneider, T.R. Using implicit bias training to improve attitudes toward women in STEM. Soc. Psychol. Educ.: An. Int. J. 2014, 17, 419–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girod, S.; Fassiotto, M.; Grewal, D.; Ku, M.C.; Sriram, N.; Nosek, B.A.; Valantine, H. Reducing implicit gender leadership bias in academic medicine with an educational intervention. Acad. Med. 2016, 91, 1143–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos, M.R.; Barreto, M.; Ellemers, N.; Moya, M.; Ferreira, L.; Calanchini, J. Exposure to sexism can decrease implicit gender stereotype bias. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2016, 46, 455–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dayal, A.; O’Connor, D.M.; Qadri, U.; Arora, V.M. Comparison of male vs female resident milestone evaluations by faculty during emergency medicine residency training. JAMA Intern. Med. 2017, 177, 651–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Files, J.A.; Mayer, A.P.; Ko, M.G.; Friedrich, P.; Jenkins, M.; Bryan, M.J.; Vegunta, S.; Wittich, C.M.; Lyle, M.A.; Melikian, R.; et al. Speaker Introductions at Internal Medicine Grand Rounds: Forms of Address Reveal Gender Bias. J. Women’s Health 2017, 26, 413–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magua, W.; Zhu, X.; Bhattacharya, A.; Filut, A.; Potvien, A.; Leatherberry, R.; Lee, Y.-G.; Jens, M.; Malikireddy, D.; Carnes, M.; et al. Are female applicants disadvantaged in National Institutes of Health peer review? Combining algorithmic text mining and qualitative methods to detect evaluative differences in R01 reviewers’ critiques. J. Women’s Health 2017, 26, 560–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dion, M.L.; Sumner, J.L.; Mitchell, S.M. Gendered Citation Patterns across Political Science and Social Science Methodology Fields. Political Anal. 2018, 26, 312–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dresden, B.E.; Dresden, A.Y.; Ridge, R.D.; Yamawaki, N. No Girls Allowed: Women in Male-Dominated Majors Experience Increased Gender Harassment and Bias. Psychol. Rep. 2018, 121, 459–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manlove, K.R.; Belou, R.M. Authors and editors assort on gender and geography in high-rank ecological publications. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0192481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller-Friedmann, J.; Childs, A.; Hillier, J. Approaching gender equity in academic chemistry: Lessons learned from successful female chemists in the UK. Chem. Educ. Res. Pract. 2018, 19, 24–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Meara, K.; Templeton, L.; Nyunt, G. Earning professional legitimacy: Challenges faced by women, underrepresented minority, and non-tenure-track faculty. Teach. Coll. Rec. 2018, 121, 1–38. [Google Scholar]

- Beasley, S.W.; Khor, S.-L.; Boakes, C.; Jenkins, D. Paradox of meritocracy in surgical selection, and of variation in the attractiveness of individual specialties: to what extent are women still disadvantaged? Anz J. Surg. 2019, 89, 171–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beeler, W.H.; Griffith, K.A.; Jones, R.D.; Chapman, C.H.; Holliday, E.B.; Lalani, N.; Wilson, E.; Bonner, J.A.; Formenti, S.C.; Hahn, S.M.; et al. Gender, Professional Experiences, and Personal Characteristics of Academic Radiation Oncology Chairs: Data to Inform the Pipeline for the 21st Century. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2019, 104, 979–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, R.; Potter, T.G.; Gray, T. Diverse perspectives: gender and leadership in the outdoor education workplace. J. Outdoor Environ. Educ. 2019, 22, 217–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davids, J.S.; Lyu, H.G.; Hoang, C.M.; Daniel, V.T.; Scully, R.E.; Xu, T.Y.; Phatak, U.R.; Damle, A.; Melnitchouk, N. Female representation and implicit gender bias at the 2017 American society of colon and rectal surgeons’ annual scientific and tripartite meeting. Dis. Colon Rectum 2019, 62, 357–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Tullio, I. Gender equality in stem: Exploring self-efficacy through gender awareness. Ital. J. Sociol. Educ. 2019, 11, 226–245. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon, G.; Kind, T.; Wright, J.; Stewart, N.; Sims, A.; Barber, A. Factors that influence the choice of academic pediatrics by underrepresented minorities. Pediatrics 2019, 144, e20182759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Shepherd, L.J.; Slavich, E.; Waters, D.; Stone, M.; Abel, R.; Johnston, E.L. Gender and cultural bias in student evaluations: Why representation matters. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0209749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerull, K.M.; Loe, M.; Seiler, K.; McAllister, J.; Salles, A. Assessing gender bias in qualitative evaluations of surgical residents. Am. J. Surg. 2019, 217, 306–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansen, M.; Schoonover, A.; Skarica, B.; Harrod, T.; Bahr, N.; Guise, J.-M. Implicit gender bias among US resident physicians. BMC Med. Educ. 2019, 19, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hardcastle, V.G.; Furst-Holloway, S.; Kallen, R.; Jacquez, F. It’s complicated: a multi-method approach to broadening participation in STEM. Equal. Divers. Incl. 2019, 38, 349–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heath, J.K.; Weissman, G.E.; Clancy, C.B.; Shou, H.; Farrar, J.T.; Dine, C.J. Assessment of Gender-Based Linguistic Differences in Physician Trainee Evaluations of Medical Faculty Using Automated Text Mining. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e193520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holman, L.; Morandin, C. Researchers collaborate with same-gendered colleagues more often than expected across the life sciences. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0216128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- James, A.; Chisnall, R.; Plank, M.J. Gender and societies: A grassroots approach to women in science. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2019, 6, 190633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, N.; Biggerstaff, D.; Szczepura, A.; Dolton, M.; Livingston, S.; Hattersley, J.; Eris, J.; Ascher, N.; Higgins, R.; Braun, H.; et al. Glass Slippers and Glass Cliffs: Fitting In and Falling Off. Transplantation 2019, 103, 1486–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukela, J.R.; Ramakrishnan, A.; Hadeed, N.; Del Valle, J. When perception is reality: Resident perception of faculty gender parity in a university-based internal medicine residency program. Perspect. Med. Educ. 2019, 8, 346–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojek, A.E.; Khanna, R.; Yim, J.W.L.; Gardner, R.; Lisker, S.; Hauer, K.E.; Lucey, C.; Sarkar, U. Differences in Narrative Language in Evaluations of Medical Students by Gender and Under-represented Minority Status. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2019, 34, 684–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salerno, P.E.; Páez-Vacas, M.; Guayasamin, J.M.; Stynoski, J.L. Male principal investigators (almost) don’t publish with women in ecology and zoology. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0218598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salles, A.; Awad, M.; Goldin, L.; Krus, K.; Lee, J.V.; Schwabe, M.T.; Lai, C.K. Estimating Implicit and Explicit Gender Bias among Health Care Professionals and Surgeons. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e196545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomson, A.; Horne, R.; Chung, C.; Marta, M.; Giovannoni, G.; Palace, J.; Dobson, R. Visibility and representation of women in multiple sclerosis research. Neurology 2019, 92, 713–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turrentine, F.E.; Dreisbach, C.N.; St Ivany, A.R.; Hanks, J.B.; Schroen, A.T. Influence of Gender on Surgical Residency Applicants’ Recommendation Letters. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2019, 228, 356–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pardal, V.; Alger, M.; Latu, I. Implicit and explicit gender stereotypes at the bargaining table: Male counterparts’ stereotypes predict women’s lower performance in dyadic face-to-face negotiations. Sex. Roles: A J. Res. 2020. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-019-01112-1 (accessed on 1 March 2020). [CrossRef]

- Uddannelses- og Forskningsministeriet. Anbefalinger fra Taskforcen for Flere kvinder i Forskning; Uddannelses- og Forskningsministeriet: København, Denmark, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Directorate-General for Research and Innovation. She Figures 2018. Eur. Comm. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gvozdanovic, J.; Maes, K. Implicit Bias in Academia: A Challenge to the Meritocratic Principle and to Women’s Careers—And What to Do about it; League of European Research Universities (LERU): Leuven, Belgium, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Pritlove, C.; Juando-Prats, C.; Ala-leppilampi, K.; Parsons, J.A. The good, the bad, and the ugly of implicit bias. Lancet 2019, 393, 502–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beel, J.; Gipp, B. Google Scholar’s Ranking Algorithm: An Introductory Overview. Comput. Sci. 2009, 6, 230–241. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, D.E. Internal compensation structuring and social bias: Experimental examinations of point. Pers. Rev. 2011, 40, 785–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalejta, R.F.; Palmenberg, A.C. Gender parity trends for invited speakers at four prominent virology conference series. J. Virol. 2017, 91, e00739-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornish, T.; Jones, P. Unconscious Bias in Higher Education: Literature Review; Equality Challenge Unit: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Steinpreis, R.E.; Anders, K.A.; Ritzke, D. The impact of gender on the review of the curricula vitae of job applicants and tenure candidates: A national empirical study. Sex. Roles 1999, 41, 509–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correll, S.J. SWS 2016 Feminist Lecture: Reducing Gender Biases In Modern Workplaces: A Small Wins Approach to Organizational Change. Gend. Soc. 2017, 31, 725–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heilman, M.E.; Haynes, M.C. Subjectivity in the appraisal process: A facilitator of gender bias in work settings. In Beyond Common Sense: Psychological Science in the Courtroom; Borgida, E., Fiske, S.T., Eds.; Blackwell Publishing Ltd.: Malden, MA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Zogmaister, C.; Arcuri, L.; Castelli, L.; Smith, E.R. The Impact of Loyalty and Equality on Implicit Ingroup Favoritism. Group Process. Intergroup Relat. 2008, 11, 493–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Brink, M.; Benschop, Y. Gender practices in the construction of academic excellence: Sheep with five legs. Organization 2011, 19, 507–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Brink, M. Scouting for talent: Appointment practices of women professors in academic medicine. Soc. Sci. Med. 2011, 72, 2033–2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moss-Racusin, C.A.; Dovidio, J.F.; Brescoll, V.L.; Graham, M.J.; Handelsman, J. Science faculty’s subtle gender biases favor male students. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 16474–16479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grogan, K.E. How the entire scientific community can confront gender bias in the workplace. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2019, 3, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knobloch-Westerwick, S.; Glynn, C.J.; Huge, M. The Matilda Effect in Science Communication: An Experiment on Gender Bias in Publication Quality Perceptions and Collaboration Interest. Sci. Commun. 2013, 35, 603–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maliniak, D.; Powers, R.; Walter, B.F. The Gender Citation Gap in International Relations. Int. Organ. 2013, 67, 889–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, J.D.; Jacquet, J.; King, M.M.; Correll, S.J.; Bergstrom, C.T. The role of gender in scholarly authorship. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e66212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaatz, A.; Gutierrez, B.; Carnes, M. Threats to objectivity in peer review: The case of gender. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2014, 35, 371–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacNell, L.; Driscoll, A.; Hunt, A.N. Whats in a Name: Exposing Gender Bias in Student Ratings of Teaching. Innov. High. Educ. 2015, 40, 291–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, J.; Williams, A.; Jones, D.; Isbel, L.; Loads, D. EqualBITE: Gender Equality in Higher Education; Sense Publishers: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- McNutt, M. Implicit bias. Science 2016, 352, 1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Lerback, J.; Hanson, B. Journals invite too few women to referee. Nature 2017, 541, 455–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahneman, D. Thinking Fast and Slow; Farrar, Straus and Giroux: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Tversky, A.; Kahneman, D. Judgment under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases. Science 1974, 185, 1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwald, A.G.; McGhee, D.E.; Schwartz, J.L. Measuring individual differences in implicit cognition: The implicit association test. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 74, 1464–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forscher, P.S.; Lai, C.K.; Axt, J.R.; Ebersole, C.R.; Herman, M.; Devine, P.G.; Nosek, B.A. A meta-analysis of procedures to change implicit measures. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2019, 117, 522–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwald, A.G.; Banaji, M.R.; Nosek, B.A. Statistically small effects of the Implicit Association Test can have societally large effects. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2015, 108, 553–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanovich, K.E. Rationality and the Reflective Mind; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Atewologun, D.; Cornish, T.; Tresh, F. Unconscious Bias Training: An. Assessment of the Evidence for Effectiveness; Equality and Human Rights Commission: Manchester, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ståhle, B. Alder, køn og rekruttering i dansk universistetsforskning; Uni-C: København, Denmark, 1999. [Google Scholar]

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).