Physical Fitness Level in 9–11-Year-Old Italian Children Is Affected by Body Mass Index and Frequency of Sport Practice but Not by Peak Height Velocity and Relative Age Effect

Abstract

1. Introduction

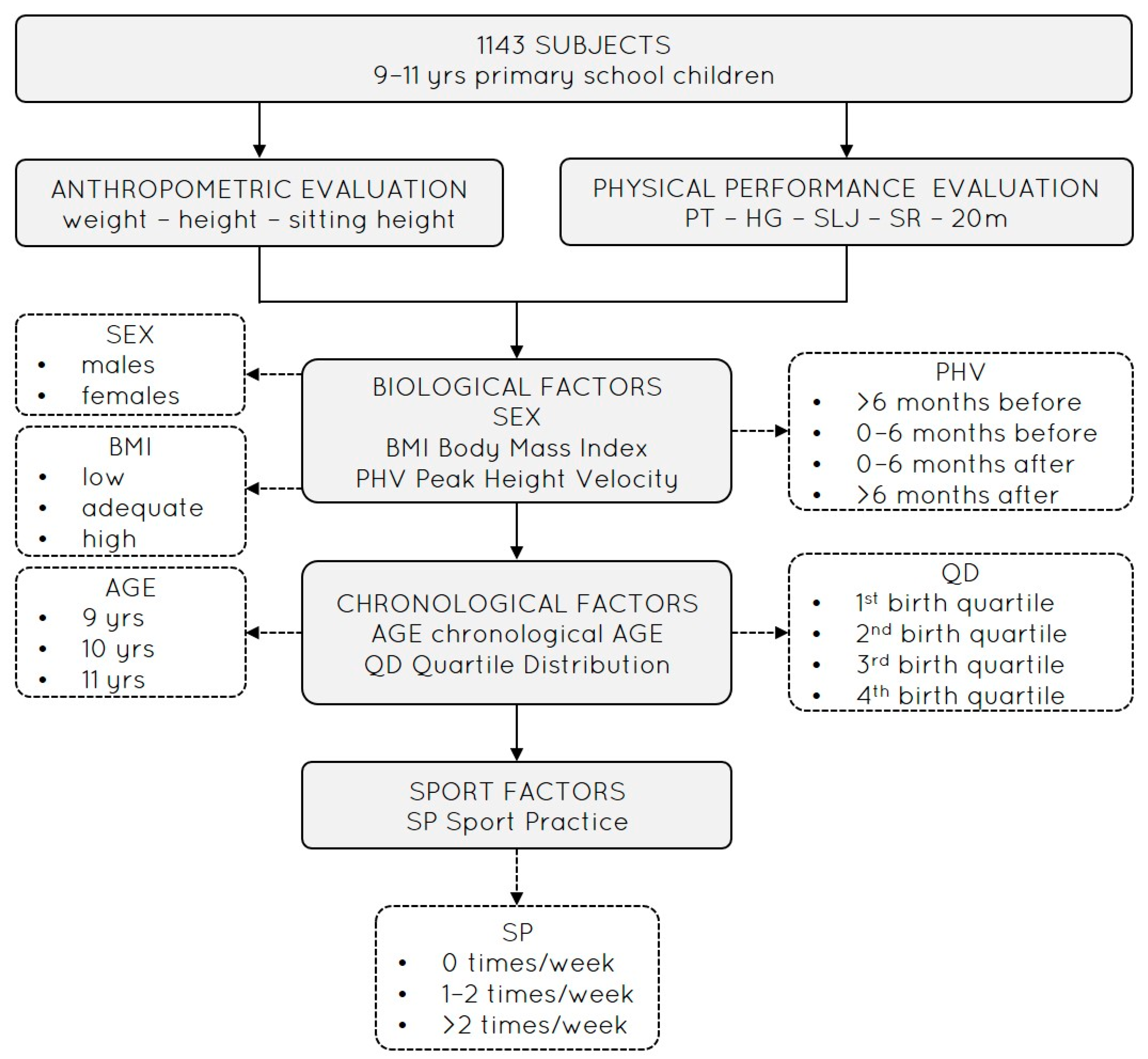

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Methods

2.3. Procedures

2.3.1. Anthropometric Parameters

2.3.2. Hand–Eye Coordination

2.3.3. Upper-Limb Strength

2.3.4. Lower-Limb Muscle Power

2.3.5. Low-Back Flexibility

2.3.6. Sprint Ability

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hamer, M.; O’Donovan, G.; Batty, G.D.; Stamatakis, E. Estimated Cardiorespiratory Fitness in Childhood and Cardiometabolic Health in Adulthood: 1970 British Cohort Study. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2020, 30, 932–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raghuveer, G.; Hartz, J.; Lubans, D.R.; Takken, T.; Wiltz, J.L.; Mietus-Snyder, M.; Perak, A.M.; Baker-Smith, C.; Pietris, N.; Edwards, N.M. Cardiorespiratory Fitness in Youth: An Important Marker of Health: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2020, 142, e101–e118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, L.E.; Stodden, D.F.; Barnett, L.M.; Lopes, V.P.; Logan, S.W.; Rodrigues, L.P.; D’Hondt, E. Motor Competence and Its Effect on Positive Developmental Trajectories of Health. Sports Med. 2015, 45, 1273–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malina, R.M.; Katzmarzyk, P.T. Physical Activity and Fitness in an International Growth Standard for Preadolescent and Adolescent Children. Food Nutr. Bull. 2006, 27, S295–S313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philippe Chaput, J.; Ortega Porcel, F.B. 2020 WHO Guidelines on Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour for Children and Adolescents Aged 5–17 Years: Summary of the Evidence. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2020, 17, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomkinson, G.R.; Lang, J.J.; Tremblay, M.S. Temporal Trends in the Cardiorespiratory Fitness of Children and Adolescents Representing 19 High-Income and Upper Middle-Income Countries between 1981 and 2014. Br. J. Sports Med. 2019, 53, 478–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupo, C.; De Pasquale, P.; Boccia, G.; Ungureanu, A.N.; Moisè, P.; Mulasso, A.; Brustio, P.R. The Most Active Child Is Not Always the Fittest: Physical Activity and Fitness Are Weakly Correlated. Sports 2023, 11, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Augste, C.; Jaitner, D. In Der Grundschule Werden Die Weichen Gestellt. Ger. J. Exerc. Sport Res. 2010, 40, 244–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnsley, R.H.; Thompson, A.H.; Barnsley, P.E. Hockey Success and Birthdate: The Relative Age Effect. Can. Assoc. Health Phys. Educ. Recreat. 1985, 51, 23–28. [Google Scholar]

- Herring, C.H.; Beyer, K.S.; Fukuda, D.H. Relative Age Effects as Evidence of Selection Bias in Major League Baseball Draftees (2013–2018). J. Strength Cond. Res. 2021, 35, 644–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tróznai, Z.; Utczás, K.; Pápai, J.; Négele, Z.; Juhász, I.; Szabó, T.; Petridis, L. Talent Selection Based on Sport-Specific Tasks Is Affected by the Relative Age Effects among Adolescent Handball Players. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brustio, P.R.; Boccia, G.; De Pasquale, P.; Lupo, C.; Ungureanu, A.N. Small Relative Age Effect Appears in Professional Female Italian Team Sports. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 19, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brustio, P.R.; Stival, M.; Boccia, G. Relative Age Effect Reversal on the Junior-to-Senior Transition in World-Class Athletics. J. Sports Sci. 2023, 41, 903–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dennis, E.; Manza, P.; Volkow, N.D. Socioeconomic Status, BMI, and Brain Development in Children. Transl. Psychiatry 2022, 12, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andermo, S.; Hallgren, M.; Nguyen, T.-T.-D.; Jonsson, S.; Petersen, S.; Friberg, M.; Romqvist, A.; Stubbs, B.; Elinder, L.S. School-Related Physical Activity Interventions and Mental Health among Children: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Med.-Open 2020, 6, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drenowatz, C.; Ferrari, G.; Greier, K.; Hinterkörner, F. Relative Age Effect in Physical Fitness during the Elementary School Years. Pediatr. Rep. 2021, 13, 322–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drenowatz, C.; Hinterkörner, F.; Greier, K. Physical Fitness and Motor Competence in Upper Austrian Elementary School Children—Study Protocol and Preliminary Findings of a State-Wide Fitness Testing Program. Front. Sports Act. Living 2021, 3, 635478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veldhuizen, S.; Cairney, J.; Hay, J.; Faught, B. Relative Age Effects in Fitness Testing in a General School Sample: How Relative Are They? J. Sports Sci. 2015, 33, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hancock, D.J.; Adler, A.L.; Côté, J. A Proposed Theoretical Model to Explain Relative Age Effects in Sport. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2013, 13, 630–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musch, J.; Grondin, S. Unequal Competition as an Impediment to Personal Development: A Review of the Relative Age Effect in Sport. Dev. Rev. 2001, 21, 147–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobley, S.P.; Till, K. Participation Trends According to Relative Age across Youth UK Rugby League. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 2017, 12, 339–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirwald, R.L.; Baxter-Jones, A.D.G.; Bailey, D.A.; Beunen, G.P. An Assessment of Maturity from Anthropometric Measurements. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2002, 34, 689–694. [Google Scholar]

- Grgic, J. Test-Retest Reliability of the EUROFIT Test Batter: A review. Sport Sci. Health 2023, 19, 381–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupo, C.; Ungureanu, A.N.; Varalda, M.; Brustio, P.R. Running Technique Is More Effective than Soccer-Specific Training for Improving the Sprint and Agility Performances with Ball Possession of Prepubescent Soccer Players. Biol. Sport 2019, 36, 249–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flanagan, S.D.; Dunn-Lewis, C.; Hatfield, D.L.; Distefano, L.J.; Fragala, M.S.; Shoap, M.; Gotwald, M.; Trail, J.; Gomez, A.L.; Volek, J.S. Developmental Differences between Boys and Girls Result in Sex-Specific Physical Fitness Changes from Fourth to Fifth Grade. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2015, 29, 175–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basterfield, L.; Burn, N.L.; Galna, B.; Karoblyte, G.; Weston, K.L. The Association between Physical Fitness, Sports Club Participation and Body Mass Index on Health-Related Quality of Life in Primary School Children from a Socioeconomically Deprived Area of England. Prev. Med. Rep. 2021, 24, 101557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prskalo, I.; Badrić, M.; Kunješić, M. The Percentage of Body Fat in Children and the Level of Their Motor Skills. Coll. Antropol. 2015, 39, 21–28. [Google Scholar]

- Birch, S.; Cummings, L.; Oxford, S.W.; Duncan, M.J. Examining Relative Age Effects in Fundamental Skill Proficiency in British Children Aged 6–11 Years. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2016, 30, 2809–2815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jarvis, S.; Rainer, P.; Ganesh, S. Fundamental Movement Proficiency of Welsh Primary School Children and the Influence of the Relative Age Effect on Skill Performance–Implications for Teaching. Educ 3 13 2023, 51, 907–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadžić, A.; Milojević, A.; Stanković, V.; Vučković, I. Relative Age Effects on Motor Performance of Seventh-Grade Pupils. Eur. Phy. Educ. Rev. 2017, 23, 534–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraiva, B.T.C.; Agostinete, R.R.; Freitas Júnior, I.F.; de Sousa, D.E.R.; Gobbo, L.A.; Tebar, W.R.; Christofaro, D.G.D. Association between Handgrip Strength and Bone Mineral Density of Brazilian Children and Adolescents Stratified by Sex: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Pediatr. 2021, 21, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Philippaerts, R.M.; Vaeyens, R.; Janssens, M.; Van Renterghem, B.; Matthys, D.; Craen, R.; Bourgois, J.; Vrijens, J.; Beunen, G.; Malina, R.M. The Relationship between Peak Height Velocity and Physical Performance in Youth Soccer Players. J. Sports Sci. 2006, 24, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brustio, P.R.; Mulasso, A.; Lupo, C.; Massasso, A.; Rainoldi, A.; Boccia, G. The Daily Mile Is Able to Improve Cardiorespiratory Fitness When Practiced Three Times a Week. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| SP Subcategories | Females (cm) | Males (cm) | β | p | ES |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 time/week | 1.37 ± 0.67 (−0.25 to 2.31) | −3.64 ± 0.73 (−5.07 to −2.20) | 5.02 | <0.001 | 0.74 |

| 1–2 times/week | 4.14 ± 0.39 (3.29 to 4.87) | −2.88 ± 0.39 (−3.66 to 2.12) | 7.02 | <0.001 | 1.03 |

| >2 times/week | 7.03 ± 0.55 (6.12 to 8.29) | −1.77 ± 0.53 (−2.65 to −0.57) | 8.80 | <0.001 | 1.30 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Varalda, M.; Ungureanu, A.N.; Coassin, A.; Maffei, N.; Li Volsi, D.; Brustio, P.R.; Lupo, C. Physical Fitness Level in 9–11-Year-Old Italian Children Is Affected by Body Mass Index and Frequency of Sport Practice but Not by Peak Height Velocity and Relative Age Effect. Sports 2026, 14, 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports14010010

Varalda M, Ungureanu AN, Coassin A, Maffei N, Li Volsi D, Brustio PR, Lupo C. Physical Fitness Level in 9–11-Year-Old Italian Children Is Affected by Body Mass Index and Frequency of Sport Practice but Not by Peak Height Velocity and Relative Age Effect. Sports. 2026; 14(1):10. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports14010010

Chicago/Turabian StyleVaralda, Mattia, Alexandru Nicolae Ungureanu, Alberto Coassin, Nicolò Maffei, Damiano Li Volsi, Paolo Riccardo Brustio, and Corrado Lupo. 2026. "Physical Fitness Level in 9–11-Year-Old Italian Children Is Affected by Body Mass Index and Frequency of Sport Practice but Not by Peak Height Velocity and Relative Age Effect" Sports 14, no. 1: 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports14010010

APA StyleVaralda, M., Ungureanu, A. N., Coassin, A., Maffei, N., Li Volsi, D., Brustio, P. R., & Lupo, C. (2026). Physical Fitness Level in 9–11-Year-Old Italian Children Is Affected by Body Mass Index and Frequency of Sport Practice but Not by Peak Height Velocity and Relative Age Effect. Sports, 14(1), 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports14010010